Submitted:

02 March 2023

Posted:

03 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

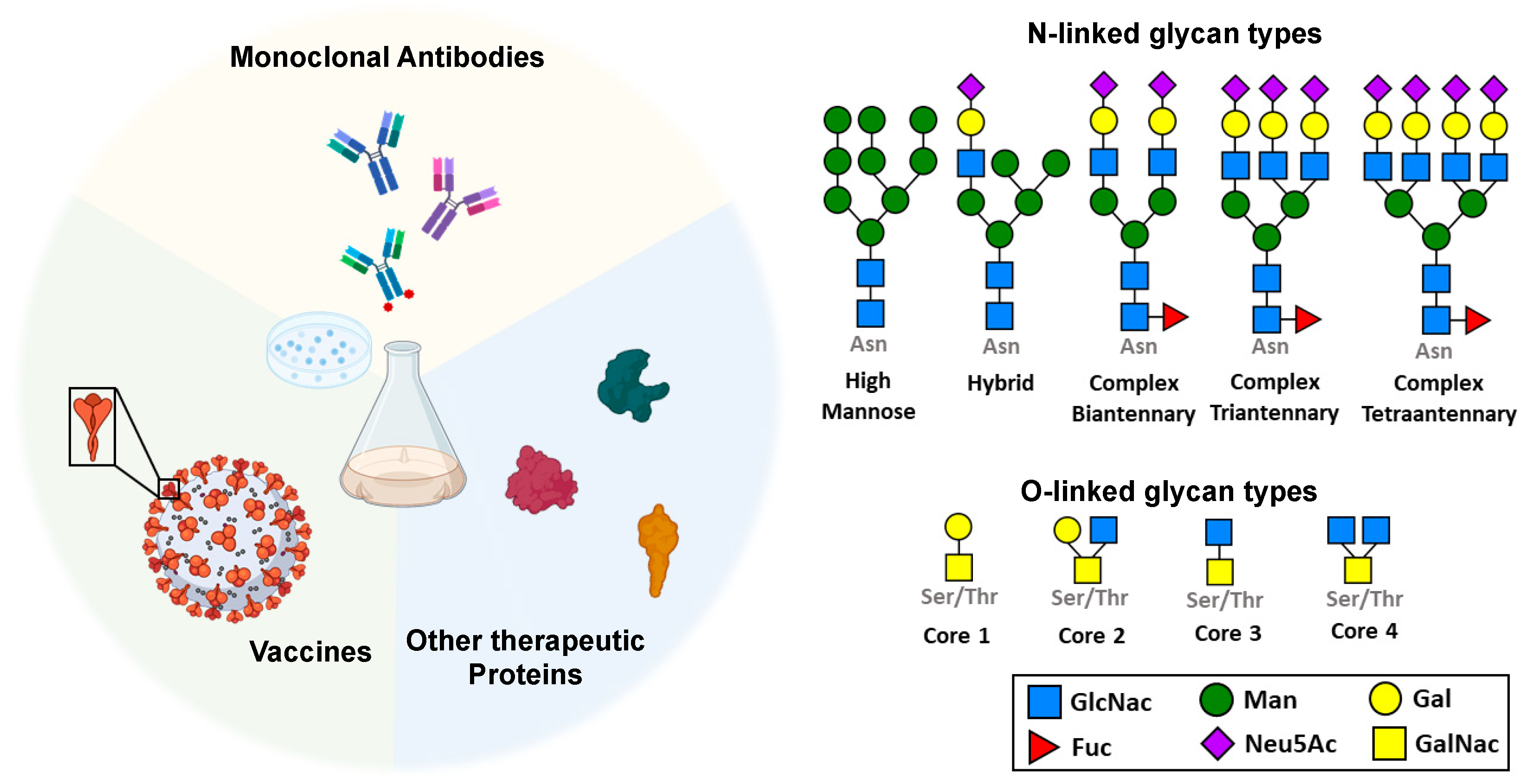

1. Glycosylation of Therapeutic Proteins

1.1. Stability

1.2. Half-life

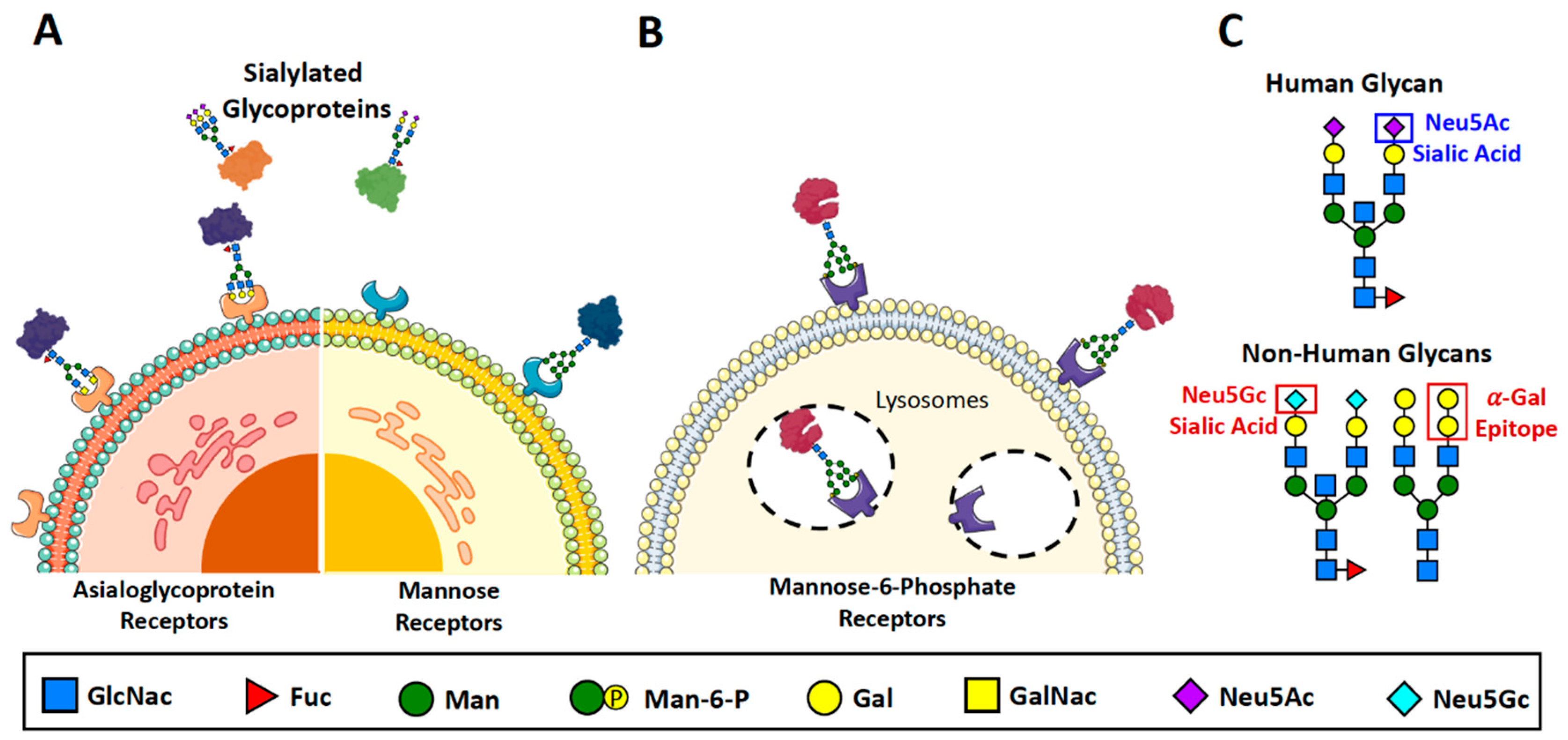

1.3. Transport and Uptake

1.3. Immunogenicity

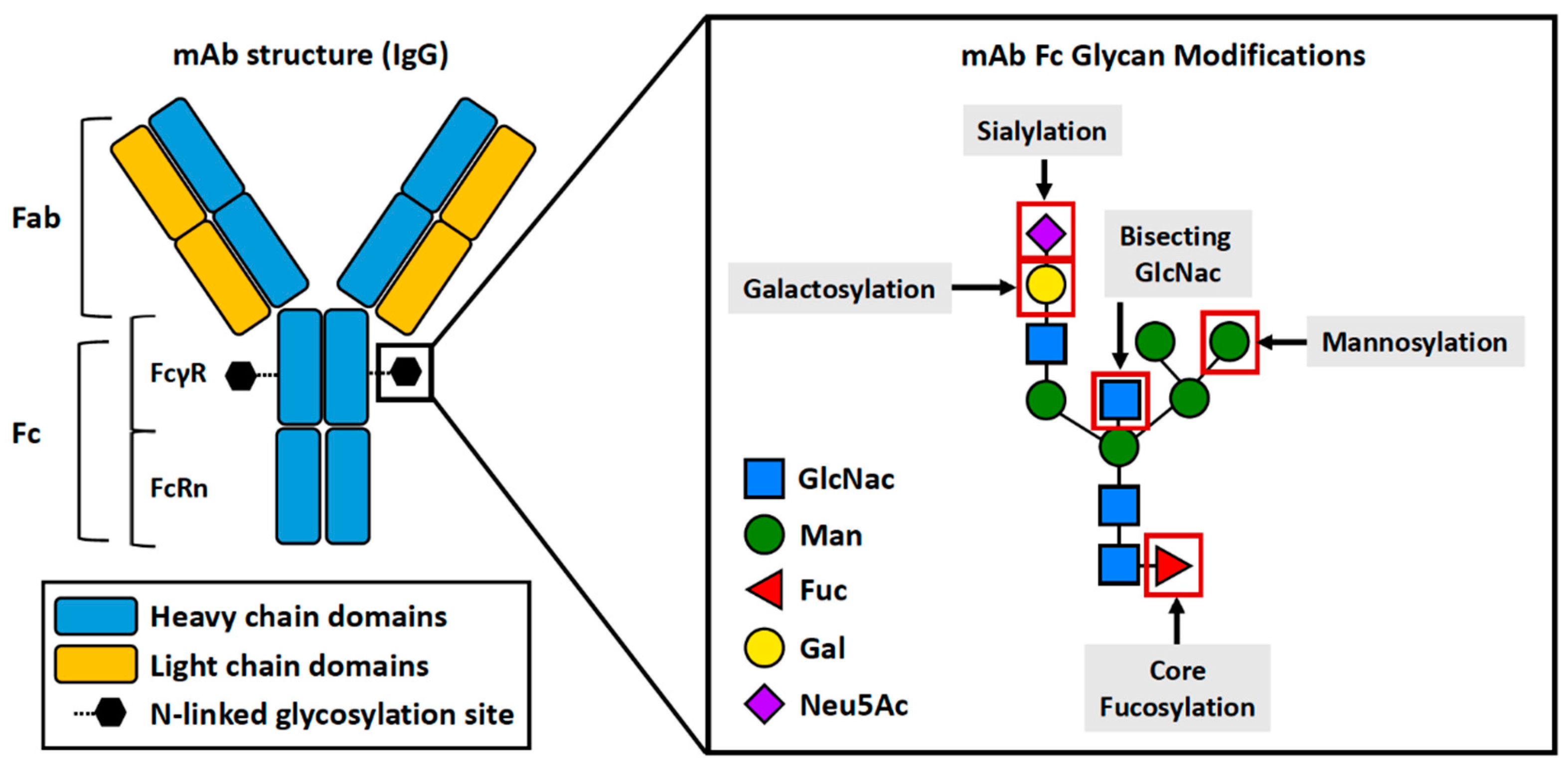

2. Monoclonal Antibodies

2.1. Fc Glycosylation and mAb Effector Function: Fucosylation

2.2. Fc Glycosylation and mAb Effector Function: Sialylation

2.3. Fc Glycosylation and mAb Effector Function: Galactosylation

2.4. Fc Glycosylation and mAb Effector Function: Bisecting GlcNac

2.5. Fc Glycosylation and mAb Effector Function: Mannosylation

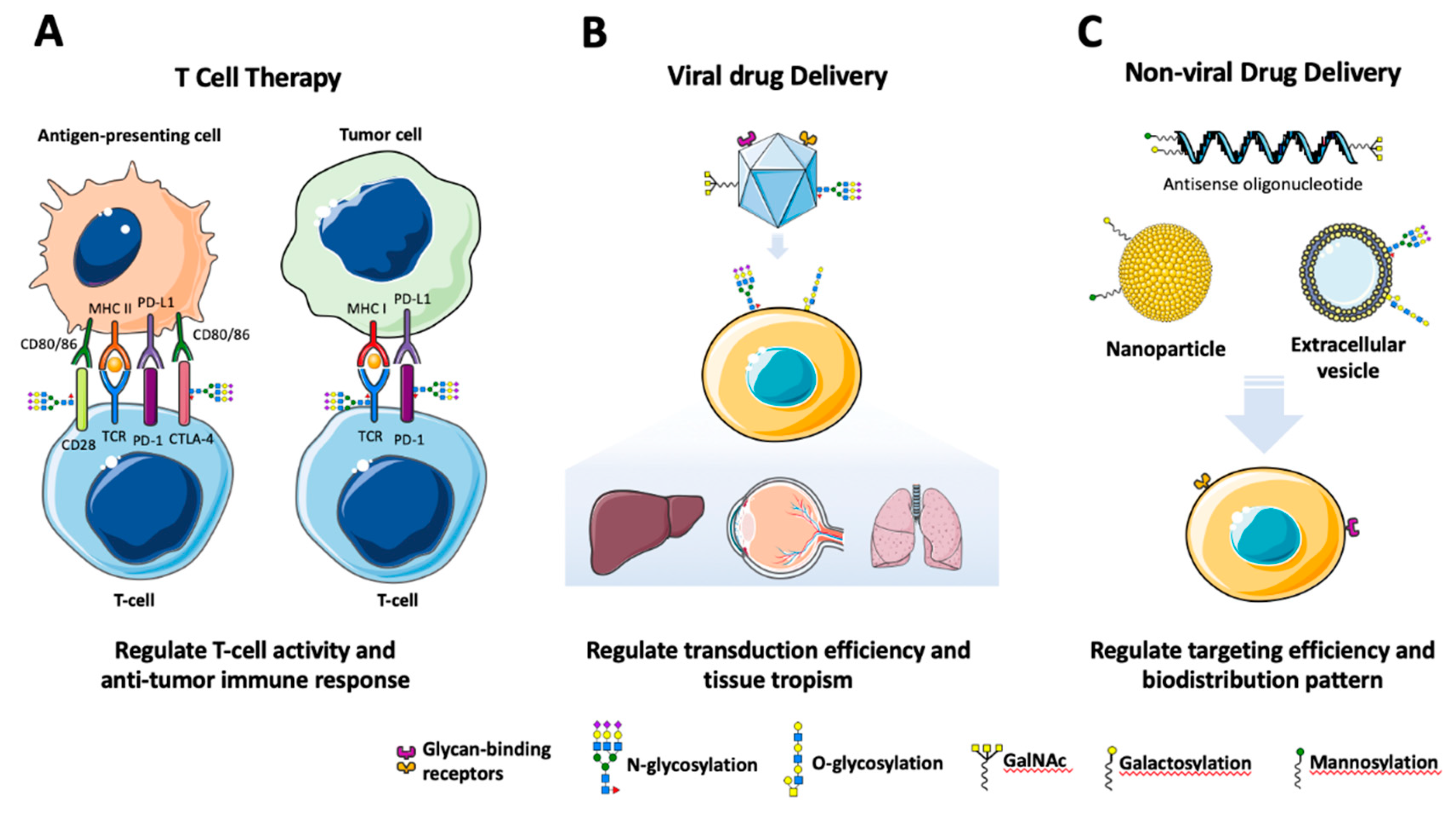

3. Future Perspectives: Next Generation Biologics

3.1. T-Cell Therapy

3.2. Viral Drug Delivery

3.3. Non-Viral Drug Delivery

4. Conclusion and Outlook

Author Contributions

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

References

- Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) Market Global Opportunity Analysis and Industry Forecast, 2018 - 2025. Available: https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/intravenous-immunoglobulin-IVIG-market.

- Expanding access to monoclonal antibody-based products: A global call to action. Available: https://www.iavi.org/phocadownload/expanding/Expanding access to monoclonal antibody-based products.pdf.

- ACHORD, D. T. , BROT, F. E., BELL, C. E. & SLY, W. S. 1978. Human beta-glucuronidase: in vivo clearance and in vitro uptake by a glycoprotein recognition system on reticuloendothelial cells. Cell, 15, 269-78.

- Altman, M.O.; Gagneux, P. Absence of Neu5Gc and Presence of Anti-Neu5Gc Antibodies in Humans—An Evolutionary Perspective. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amon, R.; Ben-Arye, S.L.; Engler, L.; Yu, H.; Lim, N.; Le Berre, L.; Harris, K.M.; Ehlers, M.R.; Gitelman, S.E.; Chen, X.; et al. Glycan microarray reveal induced IgGs repertoire shift against a dietary carbohydrate in response to rabbit anti-human thymocyte therapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 112236–112244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANDRE, S. , UNVERZAGT, C., KOJIMA, S., DONG, X., FINK, C., KAYSER, K. & GABIUS, H. J. 1997. Neoglycoproteins with the synthetic complex biantennary nonasaccharide or its alpha 2,3/alpha 2,6-sialylated derivatives: their preparation, assessment of their ligand properties for purified lectins, for tumor cells in vitro, and in tissue sections, and their biodistribution in tumor-bearing mice. Bioconjug Chem, 8, 845-55.

- ANDRE, S. , UNVERZAGT, C., KOJIMA, S., FRANK, M., SEIFERT, J., FINK, C., KAYSER, K., VON DER LIETH, C. W. & GABIUS, H. J. 2004. Determination of modulation of ligand properties of synthetic complex-type biantennary N-glycans by introduction of bisecting GlcNAc in silico, in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Biochem, 271, 118-34.

- Andresen, L.; Skovbakke, S.L.; Persson, G.; Hagemann-Jensen, M.; Hansen, K.A.; Jensen, H.; Skov, S. 2-Deoxy d-Glucose Prevents Cell Surface Expression of NKG2D Ligands through Inhibition of N-Linked Glycosylation. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 1847–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anobile, C.J.; A Talbot, J.; McCann, S.J.; Padmanabhan, V.; Robertson, W.R. Glycoform composition of serum gonadotrophins through the normal menstrual cycle and in the post-menopausal state. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 1998, 4, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, R.M.; Nimmerjahn, F.; Ashline, D.J.; Reinhold, V.N.; Paulson, J.C.; Ravetch, J.V. Recapitulation of IVIG Anti-Inflammatory Activity with a Recombinant IgG Fc. Science 2008, 320, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, R.M.; Ravetch, J.V. A Novel Role for the IgG Fc Glycan: The Anti-inflammatory Activity of Sialylated IgG Fcs. J. Clin. Immunol. 2010, 30, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, M.; Hashii, N.; Tsukimura, W.; Osumi, K.; Harazono, A.; Tada, M.; Kiyoshi, M.; Matsuda, A.; Ishii-Watabe, A. Effects of terminal galactose residues in mannose α1-6 arm of Fc-glycan on the effector functions of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. mAbs 2019, 11, 826–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ARICO, C. , BONNET, C. & JAVAUD, C. 2013. N-glycosylation humanization for production of therapeutic recombinant glycoproteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Glycosylation Engineering of Biopharmaceuticals: Methods and Protocols (2013): 45-57.

- Ashwell, G.; Harford, J. Carbohydrate-Specific Receptors of the Liver. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1982, 51, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHWELL, G. & MORELL, A. G. 1974. The role of surface carbohydrates in the hepatic recognition and transport of circulating glycoproteins. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol, 41, 99-128.

- Bakowski, K.; Vogel, S. Evolution of complexity in non-viral oligonucleotide delivery systems: from gymnotic delivery through bioconjugates to biomimetic nanoparticles. RNA Biol. 2022, 19, 1256–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BARTON, N. W. , BRADY, R. O., DAMBROSIA, J. M., DI BISCEGLIE, A. M., DOPPELT, S. H., HILL, S. C., MANKIN, H. J., MURRAY, G. J., PARKER, R. I., ARGOFF, C. E. & ET AL. 1991. Replacement therapy for inherited enzyme deficiency--macrophage-targeted glucocerebrosidase for Gaucher's disease. N Engl J Med, 324, 1464-70.

- BASILE, I. , DA SILVA, A., EL CHEIKH, K., GODEFROY, A., DAURAT, M., HARMOIS, A., PEREZ, M., CAILLAUD, C., CHARBONNE, H. V., PAU, B., GARY-BOBO, M., MORERE, A., GARCIA, M. & MAYNADIER, M. 2018. Efficient therapy for refractory Pompe disease by mannose 6-phosphate analogue grafting on acid alpha-glucosidase. J Control Release, 269, 15-23.

- Baudyš, M.; Uchio, T.; Mix, D.; Kim, S.W.; Wilson, D. Physical Stabilization of Insulin by Glycosylation. J. Pharm. Sci. 1995, 84, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, R.F.; Hwang, T.J.; Kesselheim, A.S. Pre-market development times for biologic versus small-molecule drugs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 708–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BECK, A. , COCHET, O. & WURCH, T. 2010. GlycoFi's technology to control the glycosylation of recombinant therapeutic proteins. Expert Opin Drug Discov, 5, 95-111.

- Behrens, A.-J.; Vasiljevic, S.; Pritchard, L.K.; Harvey, D.J.; Andev, R.S.; Krumm, S.A.; Struwe, W.B.; Cupo, A.; Kumar, A.; Zitzmann, N.; et al. Composition and Antigenic Effects of Individual Glycan Sites of a Trimeric HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 2695–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.L.; Vandenberghe, L.H.; Bell, P.; Limberis, M.P.; Gao, G.-P.; Van Vliet, K.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; Wilson, J.M. The AAV9 receptor and its modification to improve in vivo lung gene transfer in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2427–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BERTHE, M. L. , ESSLIMANI SAHLA, M., ROGER, P., GLEIZES, M., LEMAMY, G. J., BROUILLET, J. P. & ROCHEFORT, H. 2003. Mannose-6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor-II receptor expression levels during the progression from normal human mammary tissue to invasive breast carcinomas. Eur J Cancer, 39, 635-42.

- Bocci, V. Catabolism of therapeutic proteins and peptides with implications for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 1989, 4, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonam, S.R.; Wang, F.; Muller, S. Lysosomes as a therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 923–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonetti, P.; Diodati, G.; Drago, C.; Casarin, C.; Scaccabarozzi, S.; Realdi, G.; Ruol, A.; Alberti, A. Interferon antibodies in patients with chronic hepatitic C virus infection treated with recombinant interferon alpha-2α. J. Hepatol. 1994, 20, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bost, J.P.; Barriga, H.; Holme, M.N.; Gallud, A.; Maugeri, M.; Gupta, D.; Lehto, T.; Valadi, H.; Esbjörner, E.K.; Stevens, M.M.; et al. Delivery of Oligonucleotide Therapeutics: Chemical Modifications, Lipid Nanoparticles, and Extracellular Vesicles. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 13993–14021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, P.; Lines, A.; Patel, A. The effect of the removal of sialic acid, galactose and total carbohydrate on the functional activity of Campath-1H. Mol. Immunol. 1995, 32, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, L.J.; Velayudhan, J.; Visone, D.B.; Daugherty, K.C.; Bartron, J.L.; Coon, M.; Cornwall, C.; Hinckley, P.J.; Connell-Crowley, L. The criticality of high-resolution N-linked carbohydrate assays and detailed characterization of antibody effector function in the context of biosimilar development. mAbs 2015, 7, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRADY, R. O. , KANFER, J. N., BRADLEY, R. M. & SHAPIRO, D. 1966. Demonstration of a deficiency of glucocerebroside-cleaving enzyme in Gaucher's disease. J Clin Invest, 45, 1112-5.

- BRADY, R. O. , KANFER, J. N. & SHAPIRO, D. 1965. Metabolism of Glucocerebrosides. Ii. Evidence of an Enzymatic Deficiency in Gaucher's Disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 18, 221-5.

- Bulcha, J.T.; Wang, Y.; Ma, H.; Tai, P.W.L.; Gao, G. Viral vector platforms within the gene therapy landscape. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BULL, C. , BOLTJE, T. J., BALNEGER, N., WEISCHER, S. M., WASSINK, M., VAN GEMST, J. J., BLOEMENDAL, V. R., BOON, L., VAN DER VLAG, J., HEISE, T., DEN BROK, M. H. & ADEMA, G. J. 2018. Sialic Acid Blockade Suppresses Tumor Growth by Enhancing T-cell-Mediated Tumor Immunity. Cancer Res, 78, 3574-3588.

- Butler, M.; Spearman, M. The choice of mammalian cell host and possibilities for glycosylation engineering. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014, 30, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CADAOAS, J. , BOYLE, G., JUNGLES, S., CULLEN, S., VELLARD, M., GRUBB, J. H., JURECKA, A., SLY, W. & KAKKIS, E. 2020. Vestronidase alfa: Recombinant human beta-glucuronidase as an enzyme replacement therapy for MPS VII. Mol Genet Metab, 130, 65-76.

- CAMPBELL, C. & STANLEY, P. 1984. A dominant mutation to ricin resistance in Chinese hamster ovary cells induces UDP-GlcNAc:glycopeptide beta-4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase III activity. J Biol Chem, 259, 13370-8.

- Carter, C.R.D.; Whitmore, K.M.; Thorpe, R. The significance of carbohydrates on G-CSF: differential sensitivity of G-CSFs to human neutrophil elastase degradation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2003, 75, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadevall, N.; Nataf, J.; Viron, B.; Kolta, A.; Kiladjian, J.-J.; Martin-Dupont, P.; Michaud, P.; Papo, T.; Ugo, V.; Teyssandier, I.; et al. Pure Red-Cell Aplasia and Antierythropoietin Antibodies in Patients Treated with Recombinant Erythropoietin. New Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceaglio, N.; Etcheverrigaray, M.; Conradt, H.S.; Grammel, N.; Kratje, R.; Oggero, M. Highly glycosylated human alpha interferon: An insight into a new therapeutic candidate. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 146, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceaglio, N.; Etcheverrigaray, M.; Kratje, R.; Oggero, M. Novel long-lasting interferon alpha derivatives designed by glycoengineering. Biochimie 2008, 90, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.C.; Carter, P.J. Therapeutic antibodies for autoimmunity and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 10, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Ma, B.; Shang, S.; Tan, Z. Impact of N-Linked Glycosylation on Therapeutic Proteins. Molecules 2022, 27, 8859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-F.; Li, Z.; Ma, D.; Yu, Q. Small-molecule PD-L1 inhibitor BMS1166 abrogates the function of PD-L1 by blocking its ER export. OncoImmunology 2020, 9, 1831153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-R.; Yu, Y.-H.; Tseng, Y.-C.; Chiang, W.-L.; Chiang, M.-F.; Ko, Y.-A.; Chiu, Y.-K.; Ma, H.-H.; Wu, C.-Y.; Jan, J.-T.; et al. Vaccination of monoglycosylated hemagglutinin induces cross-strain protection against influenza virus infections. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 2476–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHEN, L. & FLIES, D. B. 2013. Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nat Rev Immunol, 13, 227-42.

- Chen, L.-R.; Chen, C.-A.; Chiu, S.-N.; Chien, Y.-H.; Lee, N.-C.; Lin, M.-T.; Hwu, W.-L.; Wang, J.-K.; Wu, M.-H. Reversal of Cardiac Dysfunction after Enzyme Replacement in Patients with Infantile-Onset Pompe Disease. J. Pediatr. 2009, 155, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Kapturczak, M.; Loiler, S.A.; Zolotukhin, S.; Glushakova, O.Y.; Madsen, K.M.; Samulski, R.J.; Hauswirth, W.W.; Campbell-Thompson, M.; Berns, K.I.; et al. Efficient Transduction of Vascular Endothelial Cells with Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Serotype 1 and 5 Vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2005, 16, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.S.; Song, J.; Kang, Y.Y.; Mok, H. Mannose-Modified Serum Exosomes for the Elevated Uptake to Murine Dendritic Cells and Lymphatic Accumulation. Macromol. Biosci. 2019, 19, e1900042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.H.; Mirakhur, B.; Chan, E.; Le, Q.-T.; Berlin, J.; Morse, M.; Murphy, B.A.; Satinover, S.M.; Hosen, J.; Mauro, D.; et al. Cetuximab-Induced Anaphylaxis and IgE Specific for Galactose-α-1,3-Galactose. New Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.A.; Wraith, J.E.; Beck, M.; Kolodny, E.H.; Pastores, G.M.; Muenzer, J.; Rapoport, D.M.; Berger, K.I.; Sidman, M.; Kakkis, E.D.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of laronidase in the treatment of mucopolysaccharidosis I. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLYNES, R. A. , TOWERS, T. L., PRESTA, L. G. & RAVETCH, J. V. 2000. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med, 6, 443-6.

- Dammen-Brower, K.; Epler, P.; Zhu, S.; Bernstein, Z.J.; Stabach, P.R.; Braddock, D.T.; Spangler, J.B.; Yarema, K.J. Strategies for Glycoengineering Therapeutic Proteins. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 863118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darlington, P.J.; Kirchhof, M.G.; Criado, G.; Sondhi, J.; Madrenas, J. Hierarchical Regulation of CTLA-4 Dimer-Based Lattice Formation and Its Biological Relevance for T Cell Inactivation. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Jiang, L.; Pan, L.Z.; LaBarre, M.J.; Anderson, D.; Reff, M. Expression of GnTIII in a recombinant anti-CD20 CHO production cell line: Expression of antibodies with altered glycoforms leads to an increase in ADCC through higher affinity for FC gamma RIII. . 2001, 74, 288–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haij, S.; Jansen, J.M.; Boross, P.; Beurskens, F.J.; Bakema, J.E.; Bos, D.L.; Martens, A.; Verbeek, J.S.; Parren, P.W.; van de Winkel, J.G.; et al. In vivo Cytotoxicity of Type I CD20 Antibodies Critically Depends on Fc Receptor ITAM Signaling. Cancer Res 2010, 70, 3209–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, G.; Treffers, L.; Plomp, R.; Bentlage, A.E.H.; de Boer, M.; Koeleman, C.A.M.; Lissenberg-Thunnissen, S.N.; Visser, R.; Brouwer, M.; Mok, J.Y.; et al. Decoding the Human Immunoglobulin G-Glycan Repertoire Reveals a Spectrum of Fc-Receptor- and Complement-Mediated-Effector Activities. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DESNICK, R. J. 2001. α-Galactosidase A Deficiency : Fabry Disease.

- Dhar, C.; Sasmal, A.; Varki, A. From “Serum Sickness” to “Xenosialitis”: Past, Present, and Future Significance of the Non-human Sialic Acid Neu5Gc. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DI MARIO, U. , ARDUINI, P., TIBERTI, C., LOMBARDI, G., PIETRAVALLE, P. & ANDREANI, D. 1986. Immunogenicity of biosynthetic human insulin. Humoral immune response in diabetic patients beginning insulin treatment and in patients previously treated with other insulins. Diabetes Res Clin Pract, 2, 317-24.

- Doebber, T.W.; Wu, M.S.; Bugianesi, R.L.; Ponpipom, M.M.; Furbish, F.S.; A Barranger, J.; O Brady, R.; Shen, T.Y. Enhanced macrophage uptake of synthetically glycosylated human placental beta-glucocerebrosidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 2193–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornelles, A.D.; Artigalás, O.; da Silva, A.A.; Ardila, D.L.V.; Alegra, T.; Pereira, T.V.; Vairo, F.P.E.; Schwartz, I.V.D. Efficacy and safety of intravenous laronidase for mucopolysaccharidosis type I: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOUGLAS, D. D. , RAKELA, J., LIN, H. J., HOLLINGER, F. B., TASWELL, H. F., CZAJA, A. J., GROSS, J. B., ANDERSON, M. L., PARENT, K., FLEMING, C. R. & ET AL. 1993. Randomized controlled trial of recombinant alpha-2a-interferon for chronic hepatitis C. Comparison of alanine aminotransferase normalization versus loss of HCV RNA and anti-HCV IgM. Dig Dis Sci, 38, 601-7.

- Edgar, L.J.; Thompson, A.J.; Vartabedian, V.F.; Kikuchi, C.; Woehl, J.L.; Teijaro, J.R.; Paulson, J.C. Sialic Acid Ligands of CD28 Suppress Costimulation of T Cells. ACS Central Sci. 2021, 7, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EGRIE, J. C. & BROWNE, J. K. 2001. Development and characterization of novel erythropoiesis stimulating protein (NESP). Br J Cancer, 84 Suppl 1, 3-10.

- Egrie, J.C.; Dwyer, E.; Browne, J.K.; Hitz, A.; A Lykos, M. Darbepoetin alfa has a longer circulating half-life and greater in vivo potency than recombinant human erythropoietin. Exp. Hematol. 2003, 31, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenpreis, E.D. Pharmacokinetic Effects of Antidrug Antibodies Occurring in Healthy Subjects After a Single Dose of Intravenous Infliximab. Drugs R&D 2017, 17, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, S.; Chang, D.; Delorme, E.; Dunn, C.; Egrie, J.; Giffin, J.; Lorenzini, T.; Talbot, C.; Hesterberg, L. Isolation and characterization of conformation sensitive antierythropoietin monoclonal antibodies: effect of disulfide bonds and carbohydrate on recombinant human erythropoietin structure. Blood 1996, 87, 2714–2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, S.; Egrie, J.; Browne, J.; Lorenzini, T.; Busse, L.; Rogers, N.; Ponting, I. Control of rHuEPO biological activity: The role of carbohydrate. Exp. Hematol. 2004, 32, 1146–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FARRELL, R. A. , MARTA, M., GAEGUTA, A. J., SOUSLOVA, V., GIOVANNONI, G. & CREEKE, P. I. 2012. Development of resistance to biologic therapies with reference to IFN-beta. Rheumatology (Oxford), 51, 590-9.

- Feins, S.; Kong, W.; Williams, E.F.; Milone, M.C.; Fraietta, J.A. An introduction to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, S3–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FENG, X. , XIE, H.-G., MALHOTRA, A. & YANG, C. F. 2022. Biologics and biosimilars : drug development and clinical affairs, Boca Raton, Taylor and Francis.

- Fenouillet, E.; Gluckman, J.C.; Jones, I.M. Functions of HIV envelope glycans. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1994, 19, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I Fernandes, A.; Gregoriadis, G. The effect of polysialylation on the immunogenicity and antigenicity of asparaginase: implication in its pharmacokinetics. Int. J. Pharm. 2001, 217, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIEDLER, W. , CRESTA, S., SCHULZE-BERGKAMEN, H., DE DOSSO, S., WEIDMANN, J., TESSARI, A., BAUMEISTER, H., DANIELCZYK, A., DIETRICH, B., GOLETZ, S., ZURLO, A., SALZBERG, M., SESSA, C. & GIANNI, L. 2018. Phase I study of tomuzotuximab, a glycoengineered therapeutic antibody against the epidermal growth factor receptor, in patients with advanced carcinomas. ESMO Open, 3, e000303.

- Filipe, V.; Que, I.; Carpenter, J.F.; Löwik, C.; Jiskoot, W. In Vivo Fluorescence Imaging of IgG1 Aggregates After Subcutaneous and Intravenous Injection in Mice. Pharm. Res. 2013, 31, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineberg, S.E.; Galloway, J.A.; Fineberg, N.S.; Rathbun, M.J.; Hufferd, S. Immunogenicity of recombinant DNA human insulin. Diabetologia 1983, 25, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flintegaard, T.V.; Thygesen, P.; Rahbek-Nielsen, H.; Levery, S.B.; Kristensen, C.; Clausen, H.; Bolt, G. N-Glycosylation Increases the Circulatory Half-Life of Human Growth Hormone. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 5326–5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, G.C.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.D.; Shah, B.; Zhang, Z. Naturally occurring glycan forms of human immunoglobulins G1 and G2. Mol. Immunol. 2010, 47, 2074–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FOSSA, S. D. , LEHNE, G., GUNDERSON, R., HJELMAAS, U. & HOLDENER, E. E. 1992. Recombinant interferon alpha-2A combined with prednisone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: treatment results, serum interferon levels and the development of antibodies. Int J Cancer, 50, 868-70.

- Fox, J.E.; Volpe, L.; Bullaro, J.; Kakkis, E.D.; Sly, W.S. First human treatment with investigational rhGUS enzyme replacement therapy in an advanced stage MPS VII patient. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2015, 114, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, B.; Vaddi, K.; Preston, C.; Mahon, E.; Cataldo, J.R.; McPherson, J.M. A comparison of the pharmacological properties of carbohydrate remodeled recombinant and placental-derived beta-glucocerebrosidase: implications for clinical efficacy in treatment of Gaucher disease. . 1999, 93, 2807–16. [Google Scholar]

- FUKUDA, M. N. , SASAKI, H. & FUKUDA, M. 1989. Survival of recombinant erythropoietin in the circulation: the role of carbohydrates. Blood, 73, 84-89.

- Furbish, F.; Steer, C.J.; Krett, N.L.; Barranger, J.A. Uptake and distribution of placental glucocerebrosidase in rat hepatic cells and effects of sequential deglycosylation. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 1981, 673, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FUTERMAN, A. H. & VAN MEER, G. 2004. The cell biology of lysosomal storage disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 5, 554-65.

- Galili, U.; E Mandrell, R.; Hamadeh, R.M.; Shohet, S.B.; Griffiss, J.M. Interaction between human natural anti-alpha-galactosyl immunoglobulin G and bacteria of the human flora. Infect. Immun. 1988, 56, 1730–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.R.; DaCosta, J.M.; Pan, J.; Muenzer, J.; Lamsa, J.C. Preclinical dose ranging studies for enzyme replacement therapy with idursulfase in a knock-out mouse model of MPS II. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2007, 91, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-García, A.; Serna, S.; Yang, Z.; Delso, I.; Taleb, V.; Hicks, T.; Artschwager, R.; Vakhrushev, S.Y.; Clausen, H.; Angulo, J.; et al. FUT8-Directed Core Fucosylation of N-glycans Is Regulated by the Glycan Structure and Protein Environment. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 9052–9065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, M.; Jain, N.K. Reduced hematopoietic toxicity, enhanced cellular uptake and altered pharmacokinetics of azidothymidine loaded galactosylated liposomes. J. Drug Target. 2006, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GERDES, C. A. , NICOLINI, V. G., HERTER, S., VAN PUIJENBROEK, E., LANG, S., ROEMMELE, M., MOESSNER, E., FREYTAG, O., FRIESS, T., RIES, C. H., BOSSENMAIER, B., MUELLER, H. J. & UMANA, P. 2013. GA201 (RG7160): a novel, humanized, glycoengineered anti-EGFR antibody with enhanced ADCC and superior in vivo efficacy compared with cetuximab. Clin Cancer Res, 19, 1126-38.

- Ghaderi, D.; E Taylor, R.; Padler-Karavani, V.; Diaz, S.; Varki, A. Implications of the presence of N-glycolylneuraminic acid in recombinant therapeutic glycoproteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 863–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetze, A.M.; Liu, Y.D.; Zhang, Z.; Shah, B.; Lee, E.; Bondarenko, P.V.; Flynn, G.C. High-mannose glycans on the Fc region of therapeutic IgG antibodies increase serum clearance in humans. Glycobiology 2011, 21, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, J.B.; Ng, S.K. Impact of host cell line choice on glycan profile. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2018, 38, 851–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golay, J.; Andrea, A.E.; Cattaneo, I. Role of Fc Core Fucosylation in the Effector Function of IgG1 Antibodies. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 929895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, R.; Chatzikleanthous, D.; Lou, G.; Giusti, F.; Bonci, A.; Taccone, M.; Brazzoli, M.; Gallorini, S.; Ferlenghi, I.; Berti, F.; et al. Mannosylation of LNP Results in Improved Potency for Self-Amplifying RNA (SAM) Vaccines. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019, 5, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, G.A.; Barton, N.W.; Pastores, G.; Dambrosia, J.M.; Banerjee, T.K.; McKee, M.A.; Parker, C.; Schiffmann, R.; Hill, S.C.; Brady, R.O. Enzyme Therapy in Type 1 Gaucher Disease: Comparative Efficacy of Mannose-Terminated Glucocerebrosidase from Natural and Recombinant Sources. Ann. Intern. Med. 1995, 122, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, G.A.; Golembo, M.; Shaaltiel, Y. Taliglucerase alfa: An enzyme replacement therapy using plant cell expression technology. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2014, 112, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorian, A.; Lee, S.-U.; Tian, W.; Chen, I.-J.; Gao, G.; Mendelsohn, R.; Dennis, J.W.; Demetriou, M. Control of T Cell-mediated Autoimmunity by Metabolite Flux to N-Glycan Biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 20027–20035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Chaffey, P.K.; Wei, X.; Gulbranson, D.R.; Ruan, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Ouyang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zeng, C.; et al. Chemically Precise Glycoengineering Improves Human Insulin. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GUDELJ, I. , LAUC, G. & PEZER, M. 2018. Immunoglobulin G glycosylation in aging and diseases. Cell Immunol, 333, 65-79.

- Halbert, C.L.; Allen, J.M.; Miller, A.D. Adeno-Associated Virus Type 6 (AAV6) Vectors Mediate Efficient Transduction of Airway Epithelial Cells in Mouse Lungs Compared to That of AAV2 Vectors. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 6615–6624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handa, A.; Muramatsu, S.-I.; Qiu, J.; Mizukami, H.; Brown, K.E. Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-3-based vectors transduce haematopoietic cells not susceptible to transduction with AAV-2-based vectors. J. Gen. Virol. 2000, 81, 2077–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmatz, P.; Giugliani, R.; Schwartz, I.; Guffon, N.; Teles, E.L.; Miranda, M.C.S.; Wraith, J.E.; Beck, M.; Arash, L.; Scarpa, M.; et al. Enzyme replacement therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis VI: A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multinational study of recombinant human N-acetylgalactosamine 4-sulfatase (recombinant human arylsulfatase B or rhASB) and follow-on, open-label extension study. J. Pediatr. 2006, 148, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HARMATZ, P. , KRAMER, W. G., HOPWOOD, J. J., SIMON, J., BUTENSKY, E., SWIEDLER, S. J. & MUCOPOLYSACCHARIDOSIS, V. I. S. G. 2005. Pharmacokinetic profile of recombinant human N-acetylgalactosamine 4-sulphatase enzyme replacement therapy in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis VI (Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome): a phase I/II study. Acta Paediatr Suppl, 94, 61-8; discussion 57.

- Harmatz, P.; Whitley, C.B.; Waber, L.; Pais, R.; Steiner, R.; Plecko, B.; Kaplan, P.; Simon, J.; Butensky, E.; Hopwood, J.J. Enzyme replacement therapy in mucopolysaccharidosis VI (Maroteaux-Lamy syndrome). J. Pediatr. 2004, 144, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmatz, P.; Whitley, C.B.; Wang, R.Y.; Bauer, M.; Song, W.; Haller, C.; Kakkis, E. A novel Blind Start study design to investigate vestronidase alfa for mucopolysaccharidosis VII, an ultra-rare genetic disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2018, 123, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, F.; Danielczyk, A.; Goletz, S. Human Cell Line-Derived Monoclonal IgA Antibodies for Cancer Immunotherapy. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HATFIELD, G. , TEPLIAKOVA, L., GINGRAS, G., STALKER, A., LI, X., AUBIN, Y. & TAM, R. Y. 2022. Specific location of galactosylation in an afucosylated antiviral monoclonal antibody affects its FcgammaRIIIA binding affinity. Front Immunol, 13, 972168.

- Hébert, E. Mannose-6-phosphate/Insulin-like Growth Factor II Receptor Expression and Tumor Development. Biosci. Rep. 2006, 26, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HENDRIKSZ, C. , SANTRA, S., JONES, S. A., GEBERHIWOT, T., JESAITIS, L., LONG, B., QI, Y., HAWLEY, S. M. & DECKER, C. 2018. Safety, immunogenicity, and clinical outcomes in patients with Morquio A syndrome participating in 2 sequential open-label studies of elosulfase alfa enzyme replacement therapy (MOR-002/MOR-100), representing 5 years of treatment. Mol Genet Metab, 123, 479-487.

- Hendriksz, C.J.; Burton, B.; Fleming, T.R.; Harmatz, P.; Hughes, D.; Jones, S.A.; Lin, S.-P.; Mengel, E.; Scarpa, M.; Valayannopoulos, V.; et al. Efficacy and safety of enzyme replacement therapy with BMN 110 (elosulfase alfa) for Morquio A syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis IVA): a phase 3 randomised placebo-controlled study. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2014, 37, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiatt, A.; Bohorova, N.; Bohorov, O.; Goodman, C.; Kim, D.; Pauly, M.H.; Velasco, J.; Whaley, K.J.; Piedra, P.A.; Gilbert, B.E.; et al. Glycan variants of a respiratory syncytial virus antibody with enhanced effector function and in vivo efficacy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 5992–5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirobe, S.; Imaeda, K.; Tachibana, M.; Okada, N. The Effects of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) Hinge Domain Post-Translational Modifications on CAR-T Cell Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodoniczky, J.; Zheng, Y.Z.; James, D.C. Control of Recombinant Monoclonal Antibody Effector Functions by Fc N-Glycan Remodeling in Vitro. Biotechnol. Prog. 2005, 21, 1644–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houde, D.; Peng, Y.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Engen, J.R. Post-translational Modifications Differentially Affect IgG1 Conformation and Receptor Binding. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2010, 9, 1716–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HUANG, H. Y. , LIAO, H. Y., CHEN, X., WANG, S. W., CHENG, C. W., SHAHED-AL-MAHMUD, M., LIU, Y. M., MOHAPATRA, A., CHEN, T. H., LO, J. M., WU, Y. M., MA, H. H., CHANG, Y. H., TSAI, H. Y., CHOU, Y. C., HSUEH, Y. P., TSAI, C. Y., HUANG, P. Y., CHANG, S. Y., CHAO, T. L., KAO, H. C., TSAI, Y. M., CHEN, Y. H., WU, C. Y., JAN, J. T., CHENG, T. R., LIN, K. I., MA, C. & WONG, C. H. 2022. Vaccination with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein lacking glycan shields elicits enhanced protective responses in animal models. Sci Transl Med, 14, eabm0899.

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.-L.; Li, Z.-L.; Du, T.; Chen, Y.-H.; Wang, Y.; Ni, H.-H.; Zhang, K.-M.; Mai, J.; Hu, B.-X.; et al. FUT8-mediated aberrant N-glycosylation of B7H3 suppresses the immune response in triple-negative breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, A.L.; Stukenbrok, H. An electron microscope autoradiographic study of the carbohydrate recognition systems in rat liver. II. Intracellular fates of the 125I-ligands. J. Cell Biol. 1979, 83, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiwata, T.; Bergmann, U.; Kornmann, M.; Lopez, M.; Beger, H.G.; Korc, M. Altered Expression of Insulin-like Growth Factor II Receptor in Human Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas 1997, 15, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, P.P.; Geysens, S.; Vervecken, W.; Contreras, R.; Callewaert, N. Engineering complex-type N-glycosylation in Pichia pastoris using GlycoSwitch technology. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 4, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Kesharwani, P.; Garg, N.K.; Jain, A.; Jain, S.A.; Jain, A.K.; Nirbhavane, P.; Ghanghoria, R.; Tyagi, R.K.; Katare, O.P. Galactose engineered solid lipid nanoparticles for targeted delivery of doxorubicin. Colloids Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2015, 134, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferis, R. Glycosylation as a strategy to improve antibody-based therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferis, R. Recombinant antibody therapeutics: the impact of glycosylation on mechanisms of action. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 30, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferis, R. Isotype and glycoform selection for antibody therapeutics. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 526, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JEPPSSON, J. O. , LARSSON, C. & ERIKSSON, S. 1975. Characterization of alpha1-antitrypsin in the inclusion bodies from the liver in alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency. N Engl J Med, 293, 576-9.

- June, C.H.; O’Connor, R.S.; Kawalekar, O.U.; Ghassemi, S.; Milone, M.C. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science 2018, 359, 1361–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakkis, E.; Matynia, A.; Jonas, A.; Neufeld, E. Overexpression of the Human Lysosomal Enzyme α-L-Iduronidase in Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells. Protein Expr. Purif. 1994, 5, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KAKKIS, E. D. , MUENZER, J., TILLER, G. E., WABER, L., BELMONT, J., PASSAGE, M., IZYKOWSKI, B., PHILLIPS, J., DOROSHOW, R., WALOT, I., HOFT, R. & NEUFELD, E. F. 2001. Enzyme-replacement therapy in mucopolysaccharidosis I. N Engl J Med, 344, 182-8.

- Kaludov, N.; Brown, K.E.; Walters, R.W.; Zabner, J.; Chiorini, J.A. Adeno-Associated Virus Serotype 4 (AAV4) and AAV5 Both Require Sialic Acid Binding for Hemagglutination and Efficient Transduction but Differ in Sialic Acid Linkage Specificity. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 6884–6893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamei, N.; Fukui, R.; Suzuki, Y.; Kajihara, Y.; Kinoshita, M.; Kakehi, K.; Hojo, H.; Tezuka, K.; Tsuji, T. Definitive evidence that a single N-glycan among three glycans on inducible costimulator is required for proper protein trafficking and ligand binding. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 391, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, Y.; Nimmerjahn, F.; Ravetch, J.V. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Immunoglobulin G Resulting from Fc Sialylation. Science 2006, 313, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.-Y.; Shin, K.K.; Kim, H.H.; Min, J.-K.; Ji, E.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Kwon, O.; Oh, D.-B. Lysosomal Targeting Enhancement by Conjugation of Glycopeptides Containing Mannose-6-phosphate Glycans Derived from Glyco-engineered Yeast. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, A.; Achord, D.T.; Sly, W.S. Phosphohexosyl components of a lysosomal enzyme are recognized by pinocytosis receptors on human fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1977, 74, 2026–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karottki, K.J.l.C.; Hefzi, H.; Xiong, K.; Shamie, I.; Hansen, A.H.; Li, S.; Pedersen, L.E.; Li, S.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, G.M.; et al. Awakening dormant glycosyltransferases in CHO cells with CRISPRa. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 117, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KARPUSAS, M. , WHITTY, A., RUNKEL, L. & HOCHMAN, P. 1998. The structure of human interferon-beta: implications for activity. Cell Mol Life Sci, 54, 1203-16.

- Kim, B.; Sun, R.; Oh, W.; Kim, A.M.J.; Schwarz, J.R.; Lim, S.O. Saccharide analog, 2-deoxy-d-glucose enhances 4-1BB-mediated antitumor immunity via PD-L1 deglycosylation. Mol. Carcinog. 2020, 59, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Seo, J.; Chung, Y.; Ji, H.-J.; Lee, J.; Sohn, J.; Lee, B.; Jo, E.-C. Comparative study of idursulfase beta and idursulfase in vitro and in vivo. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 62, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Jin, H.; Kim, H.W.; Cho, M.-H.; Cho, C.S. Mannosylated chitosan nanoparticle–based cytokine gene therapy suppressed cancer growth in BALB/c mice bearing CT-26 carcinoma cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2006, 5, 1723–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishnani, P.S.; Nicolino, M.; Voit, T.; Rogers, R.C.; Tsai, A.C.-H.; Waterson, J.; Herman, G.E.; Amalfitano, A.; Thurberg, B.L.; Richards, S.; et al. Chinese hamster ovary cell-derived recombinant human acid α-glucosidase in infantile-onset Pompe disease. J. Pediatr. 2006, 149, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- KIVISAKK, P. , ALM, G. V., FREDRIKSON, S. & LINK, H. 2000. Neutralizing and binding anti-interferon-beta (IFN-beta) antibodies. A comparison between IFN-beta-1a and IFN-beta-1b treatment in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol, 7, 27-34.

- Kolbeck, R.; Kozhich, A.; Koike, M.; Peng, L.; Andersson, C.K.; Damschroder, M.M.; Reed, J.L.; Woods, R.; Dall'Acqua, W.W.; Stephens, G.L.; et al. MEDI-563, a humanized anti–IL-5 receptor α mAb with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity function. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrad, M.W.; Childs, A.L.; Merigan, T.C.; Borden, E.C. Assessment of the antigenic response in humans to a recombinant mutant interferon beta. J. Clin. Immunol. 1987, 7, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krambeck, F.J.; Bennun, S.V.; Andersen, M.R.; Betenbaugh, M.J. Model-based analysis of N-glycosylation in Chinese hamster ovary cells. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0175376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, J.A.; Witzigmann, D.; Thomson, S.B.; Chen, S.; Leavitt, B.R.; Cullis, P.R.; van der Meel, R. The current landscape of nucleic acid therapeutics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumpel, B.M.; Rademacher, T.W.; A Rook, G.; Williams, P.J.; Wilson, I.B. Galactosylation of human IgG monoclonal anti-D produced by EBV-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cell lines is dependent on culture method and affects Fc receptor-mediated functional activity. . 1994, 5, 143–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwon, K.-S.; Yu, M.-H. Effect of glycosylation on the stability of α1-antitrypsin toward urea denaturation and thermal deactivation. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Gen. Subj. 1997, 1335, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmann, R.H. Enzyme replacement therapy for lysosomal storage diseases. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2011, 23, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Largent, B.L.; Walton, K.M.; A Hoppe, C.; Lee, Y.C.; Schnaar, R.L. Carbohydrate-specific adhesion of alveolar macrophages to mannose-derivatized surfaces. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 1764–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larocca, A.P.; Leung, S.C.; Marcus, S.G.; Colby, C.B.; Borden, E.C. Evaluation of neutralizing antibodies in patients treated with recombinant interferon-beta ser. . 1989, S51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lassiter, G.; Bergeron, C.; Guedry, R.; Cucarola, J.; Kaye, A.M.; Cornett, E.M.; Kaye, A.D.; Varrassi, G.; Viswanath, O.; Urits, I. Belantamab Mafodotin to Treat Multiple Myeloma: A Comprehensive Review of Disease, Drug Efficacy and Side Effects. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, K.S.; Partridge, E.A.; Grigorian, A.; Silvescu, C.I.; Reinhold, V.N.; Demetriou, M.; Dennis, J.W. Complex N-Glycan Number and Degree of Branching Cooperate to Regulate Cell Proliferation and Differentiation. Cell 2007, 129, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laube, F. Mannose-6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor-II receptor in human melanoma cells: effect of ligands and antibodies on the receptor expression. . 2009, 29, 1383–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Qi, Y.; Im, W. Effects of N-glycosylation on protein conformation and dynamics: Protein Data Bank analysis and molecular dynamics simulation study. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, srep08926–8926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Jin, X.; Zhang, K.; Copertino, L.; Andrews, L.; Baker-Malcolm, J.; Geagan, L.; Qiu, H.; Seiger, K.; Barngrover, D.; et al. A biochemical and pharmacological comparison of enzyme replacement therapies for the glycolipid storage disorder Fabry disease. Glycobiology 2003, 13, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yang, C.; Xia, Y.; Bertino, A.; Glaspy, J.; Roberts, M.; Kuter, D.J. Thrombocytopenia caused by the development of antibodies to thrombopoietin. Blood 2001, 98, 3241–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; DiLillo, D.J.; Bournazos, S.; Giddens, J.P.; Ravetch, J.V.; Wang, L.-X. Modulating IgG effector function by Fc glycan engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, 3485–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Chiang, A.W.T.; Hansen, A.H.; Arnsdorf, J.; Schoffelen, S.; Sorrentino, J.T.; Kellman, B.P.; Bao, B.; Voldborg, B.G.; Lewis, N.E. A Markov model of glycosylation elucidates isozyme specificity and glycosyltransferase interactions for glycoengineering. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2020, 2, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linehan, S.A.; Martínez-Pomares, L.; Stahl, P.D.; Gordon, S. Mannose Receptor and Its Putative Ligands in Normal Murine Lymphoid and Nonlymphoid Organs: In Situ Expression of Mannose Receptor by Selected Macrophages, Endothelial Cells, Perivascular Microglia, and Mesangial Cells, but not Dendritic Cells. J. Exp. Med. 1999, 189, 1961–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIS, H. & SHARON, N. 1993. Protein glycosylation. Structural and functional aspects. Eur J Biochem, 218, 1-27.

- LIU, H. , NOWAK, C., ANDRIEN, B., SHAO, M., PONNIAH, G. & NEILL, A. 2017. Impact of IgG Fc-Oligosaccharides on Recombinant Monoclonal Antibody Structure, Stability, Safety, and Efficacy. Biotechnol Prog, 33, 1173-1181.

- Liu, J.; Wang, G.; Liu, L.; Wu, R.; Wu, Y.; Fang, C.; Zhou, X.; Jiao, J.; Gu, Y.; Zhou, H.; et al. Study of the interactions of a novel monoclonal antibody, mAb059c, with the hPD-1 receptor. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LIU, K. , TAN, S., JIN, W., GUAN, J., WANG, Q., SUN, H., QI, J., YAN, J., CHAI, Y., WANG, Z., DENG, C. & GAO, G. F. 2020. N-glycosylation of PD-1 promotes binding of camrelizumab. EMBO Rep, 21, e51444.

- Liu, L. Antibody Glycosylation and Its Impact on the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Monoclonal Antibodies and Fc-Fusion Proteins. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 1866–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Sambrooks, C.; Shrimal, S.; Khodier, C.; Flaherty, D.P.; Rinis, N.; Charest, J.C.; Gao, N.; Zhao, P.; Wells, L.; A Lewis, T.; et al. Oligosaccharyltransferase inhibition induces senescence in RTK-driven tumor cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, M.; Liu, K.; He, J.; Ma, D.; Ma, X.; Tan, S.; Gao, G.F.; et al. PD-1 N58-Glycosylation-Dependent Binding of Monoclonal Antibody Cemiplimab for Immune Checkpoint Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 826045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.-M.; Hwang, Y.-C.; Liu, I.-J.; Lee, C.-C.; Tsai, H.-Z.; Li, H.-J.; Wu, H.-C. Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases. J. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 27, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, D.L.; Pereira, D.S.; Zhu, Z.; Hicklin, D.J.; Bohlen, P. Monoclonal antibody therapeutics and apoptosis. Oncogene 2003, 22, 9097–9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundahl, M.L.E.; Fogli, S.; Colavita, P.E.; Scanlan, E.M. Aggregation of protein therapeutics enhances their immunogenicity: causes and mitigation strategies. RSC Chem. Biol. 2021, 2, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Guan, X.; Li, Y.; Shang, S.; Li, J.; Tan, Z. Protein Glycoengineering: An Approach for Improving Protein Properties. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.Y.; A Mikolajczak, S.; Yoshida, T.; Yoshida, R.; Kelvin, D.J.; Ochi, A. CD28 T cell costimulatory receptor function is negatively regulated by N-linked carbohydrates. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 317, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maack, T.; Johnson, V.; Kau, S.T.; Figueiredo, J.; Sigulem, D. Renal filtration, transport, and metabolism of low-molecular-weight proteins: A review. Kidney Int. 1979, 16, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MACHER, B. A. & GALILI, U. 2008. The Galalpha1,3Galbeta1,4GlcNAc-R (alpha-Gal) epitope: a carbohydrate of unique evolution and clinical relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta, 1780, 75-88.

- Madigan, V.J.; Asokan, A. Engineering AAV receptor footprints for gene therapy. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2016, 18, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madireddi, S.; Eun, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-W.; Nemčovičová, I.; Mehta, A.K.; Zajonc, D.M.; Nishi, N.; Niki, T.; Hirashima, M.; Croft, M. Galectin-9 controls the therapeutic activity of 4-1BB–targeting antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 2014, 211, 1433–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, I.; Green, M.D. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Considerations in the Development of Therapeutic Proteins. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2005, 44, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MAJEWSKA, N. I. , TEJADA, M. L., BETENBAUGH, M. J. & AGARWAL, N. 2020. N-Glycosylation of IgG and IgG-Like Recombinant Therapeutic Proteins: Why Is It Important and How Can We Control It? Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng, 11, 311-338.

- Markov, O.V.; Mironova, N.L.; Shmendel, E.V.; Serikov, R.N.; Morozova, N.G.; Maslov, M.A.; Vlassov, V.V.; Zenkova, M.A. Multicomponent mannose-containing liposomes efficiently deliver RNA in murine immature dendritic cells and provide productive anti-tumour response in murine melanoma model. J. Control. Release 2015, 213, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MARTINEZ-POMARES, L. 2012. The mannose receptor. J Leukoc Biol, 92, 1177-86.

- Mary, B.; Maurya, S.; Arumugam, S.; Kumar, V.; Jayandharan, G.R. Post-translational modifications in capsid proteins of recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) 1-rh10 serotypes. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 4964–4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mary, B.; Maurya, S.; Kumar, M.; Bammidi, S.; Kumar, V.; Jayandharan, G.R. Molecular Engineering of Adeno-Associated Virus Capsid Improves Its Therapeutic Gene Transfer in Murine Models of Hemophilia and Retinal Degeneration. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 4738–4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, S.; Keiser, K.; Nair, J.K.; Charisse, K.; Manoharan, R.M.; Kretschmer, P.; Peng, C.G.; Kel’in, A.V.; Kandasamy, P.; Willoughby, J.L.; et al. siRNA Conjugates Carrying Sequentially Assembled Trivalent N-Acetylgalactosamine Linked Through Nucleosides Elicit Robust Gene Silencing In Vivo in Hepatocytes. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MAYEUX, P. & CASADEVALL, N. 2003. Antibodies to endogenous and recombinant erythropoietin.. In: MOLINEUX, G., FOOTE, M. A. & ELLIOTT, S. G. (eds.) Erythropoietins and Erythropoiesis. Milestones in Drug Therapy. Basel: Birkhäuser Basel.

- McCafferty, E.H.; Scott, L.J. Vestronidase Alfa: A Review in Mucopolysaccharidosis VII. BioDrugs 2019, 33, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MEREITER, S. , BALMANA, M., CAMPOS, D., GOMES, J. & REIS, C. A. 2019. Glycosylation in the Era of Cancer-Targeted Therapy: Where Are We Heading? Cancer Cell, 36, 6-16.

- MEURIS, L. , SANTENS, F., ELSON, G., FESTJENS, N., BOONE, M., DOS SANTOS, A., DEVOS, S., ROUSSEAU, F., PLETS, E., HOUTHUYS, E., MALINGE, P., MAGISTRELLI, G., CONS, L., CHATEL, L., DEVREESE, B. & CALLEWAERT, N. 2014. GlycoDelete engineering of mammalian cells simplifies N-glycosylation of recombinant proteins. Nat Biotechnol, 32, 485-9.

- Mevel, M.; Bouzelha, M.; Leray, A.; Pacouret, S.; Guilbaud, M.; Penaud-Budloo, M.; Alvarez-Dorta, D.; Dubreil, L.; Gouin, S.G.; Combal, J.P.; et al. Chemical modification of the adeno-associated virus capsid to improve gene delivery. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.L.; Chapman, M.S. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) cell entry: structural insights. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 30, 432–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mietzsch, M.; Broecker, F.; Reinhardt, A.; Seeberger, P.H.; Heilbronn, R. Differential Adeno-Associated Virus Serotype-Specific Interaction Patterns with Synthetic Heparins and Other Glycans. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 2991–3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mimura, Y.; Katoh, T.; Saldova, R.; O'Flaherty, R.; Izumi, T.; Mimura-Kimura, Y.; Utsunomiya, T.; Mizukami, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Matsumoto, T.; et al. Glycosylation engineering of therapeutic IgG antibodies: challenges for the safety, functionality and efficacy. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minnelli, C.; Cianfruglia, L.; Laudadio, E.; Galeazzi, R.; Pisani, M.; Crucianelli, E.; Bizzaro, D.; Armeni, T.; Mobbili, G. Selective induction of apoptosis in MCF7 cancer-cell by targeted liposomes functionalised with mannose-6-phosphate. J. Drug Target. 2017, 26, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, N.; Sinha, S.; Ramya, T.N.; Surolia, A. N-linked oligosaccharides as outfitters for glycoprotein folding, form and function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006, 31, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mkhikian, H.; Grigorian, A.; Li, C.F.; Chen, H.-L.; Newton, B.; Zhou, R.W.; Beeton, C.; Torossian, S.; Tatarian, G.G.; Lee, S.-U.; et al. Genetics and the environment converge to dysregulate N-glycosylation in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollé, L.M.; Smyth, C.H.; Yuen, D.; Johnston, A.P.R. Nanoparticles for vaccine and gene therapy: Overcoming the barriers to nucleic acid delivery. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 14, e1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, N.; Silva, M.; Castano, A.P.; Maus, M.V.; Sackstein, R. Glycoengineering of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells to enforce E-selectin binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 18465–18474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorkens, E.; Meuwissen, N.; Huys, I.; Declerck, P.; Vulto, A.G.; Simoens, S. The Market of Biopharmaceutical Medicines: A Snapshot of a Diverse Industrial Landscape. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, A.G.; Gregoriadis, G.; Scheinberg, I.H.; Hickman, J.; Ashwell, G. The Role of Sialic Acid in Determining the Survival of Glycoproteins in the Circulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1971, 246, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, A.G.; A Irvine, R.; Sternlieb, I.; Scheinberg, I.H.; Ashwell, G. Physical and chemical studies on ceruloplasmin. V. Metabolic studies on sialic acid-free ceruloplasmin in vivo.. 1968, 243, 155–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOSSNER, E. , BRUNKER, P., MOSER, S., PUNTENER, U., SCHMIDT, C., HERTER, S., GRAU, R., GERDES, C., NOPORA, A., VAN PUIJENBROEK, E., FERRARA, C., SONDERMANN, P., JAGER, C., STREIN, P., FERTIG, G., FRIESS, T., SCHULL, C., BAUER, S., DAL PORTO, J., DEL NAGRO, C., DABBAGH, K., DYER, M. J., POPPEMA, S., KLEIN, C. & UMANA, P. 2010. Increasing the efficacy of CD20 antibody therapy through the engineering of a new type II anti-CD20 antibody with enhanced direct and immune effector cell-mediated B-cell cytotoxicity. Blood, 115, 4393-402.

- Muenzer, J.; Gucsavas-Calikoglu, M.; McCandless, S.E.; Schuetz, T.J.; Kimura, A. A phase I/II clinical trial of enzyme replacement therapy in mucopolysaccharidosis II (Hunter syndrome). Abstr. 2007 Meet. Soc. Inherit. Metab. Disord. 2007, 90, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MUENZER, J. , LAMSA, J. C., GARCIA, A., DACOSTA, J., GARCIA, J. & TRECO, D. A. 2002. Enzyme replacement therapy in mucopolysaccharidosis type II (Hunter syndrome): a preliminary report. Acta Paediatr Suppl, 91, 98-9.

- Muenzer, J.; Wraith, J.E.; Beck, M.; Giugliani, R.; Harmatz, P.; Eng, C.M.; Vellodi, A.; Martin, R.; Ramaswami, U.; Gucsavas-Calikoglu, M.; et al. A phase II/III clinical study of enzyme replacement therapy with idursulfase in mucopolysaccharidosis II (Hunter syndrome). Genet. Med. 2006, 8, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, J.K.; Willoughby, J.L.S.; Chan, A.; Charisse, K.; Alam, R.; Wang, Q.; Hoekstra, M.; Kandasamy, P.; Kel’in, A.V.; Milstein, S.; et al. Multivalent N-Acetylgalactosamine-Conjugated siRNA Localizes in Hepatocytes and Elicits Robust RNAi-Mediated Gene Silencing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16958–16961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narhi, L.; Arakawa, T.; Aoki, K.; Elmore, R.; Rohde, M.; Boone, T.; Strickland, T. The effect of carbohydrate on the structure and stability of erythropoietin. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 23022–23026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NEUFELD, E. F. & MUENZER, J. 1989. The metabolic basis of inherited disease, New York, McGraw-Hill.

- Ng, R.; Govindasamy, L.; Gurda, B.L.; McKenna, R.; Kozyreva, O.G.; Samulski, R.J.; Parent, K.N.; Baker, T.S.; Agbandje-McKenna, M. Structural Characterization of the Dual Glycan Binding Adeno-Associated Virus Serotype 6. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 12945–12957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.H.; Tangvoranuntakul, P.; Varki, A. Effects of Natural Human Antibodies against a Nonhuman Sialic Acid That Metabolically Incorporates into Activated and Malignant Immune Cells. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIMMERJAHN, F. , ANTHONY, R. M. & RAVETCH, J. V. 2007. Agalactosylated IgG antibodies depend on cellular Fc receptors for in vivo activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104, 8433-7.

- Nimmerjahn, F.; Ravetch, J.V. Anti-Inflammatory Actions of Intravenous Immunoglobulin. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 26, 513–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida-Aoki, N.; Tominaga, N.; Kosaka, N.; Ochiya, T. Altered biodistribution of deglycosylated extracellular vesicles through enhanced cellular uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1713527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, T.; Kimura, N.; Jitsuhara, Y.; Uchida, M.; Ochi, F.; Yamaguchi, H. N-Glycans protect proteins from protease digestion through their binding affinities for aromatic amino acid residues. J. Biochem. 2000, 127, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nose, M.; Wigzell, H. Biological significance of carbohydrate chains on monoclonal antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1983, 80, 6632–6636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Neil, B.H.; Allen, R.; Spigel, D.R.; Stinchcombe, T.E.; Moore, D.T.; Berlin, J.D.; Goldberg, R.M. High Incidence of Cetuximab-Related Infusion Reactions in Tennessee and North Carolina and the Association With Atopic History. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 3644–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogata, S.; Shimizu, C.; Franco, A.; Touma, R.; Kanegaye, J.T.; Choudhury, B.P.; Naidu, N.N.; Kanda, Y.; Hoang, L.T.; Hibberd, M.L.; et al. Treatment Response in Kawasaki Disease Is Associated with Sialylation Levels of Endogenous but Not Therapeutic Intravenous Immunoglobulin G. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e81448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, D.-B. Glyco-engineering strategies for the development of therapeutic enzymes with improved efficacy for the treatment of lysosomal storage diseases. BMB Rep. 2015, 48, 438–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh-Eda, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Hattori, K.; Kuboniwa, H.; Kojima, T.; Orita, T.; Tomonou, K.; Yamazaki, T.; Ochi, N. O-linked sugar chain of human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor protects it against polymerization and denaturation allowing it to retain its biological activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 11432–11435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Chikuma, S.; Kondo, T.; Hibino, S.; Machiyama, H.; Yokosuka, T.; Nakano, M.; Yoshimura, A. Blockage of Core Fucosylation Reduces Cell-Surface Expression of PD-1 and Promotes Anti-tumor Immune Responses of T Cells. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, M.; Nakai, M.; Nakayama, C.; Yanagi, H.; Matsui, H.; Noguchi, H.; Namiki, M.; Sakai, J.; Kadota, K.; Fukui, M.; et al. Purification and characterization of three forms of differently glycosylated recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1991, 286, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OKERBLOM, J. & VARKI, A. 2017. Biochemical, Cellular, Physiological, and Pathological Consequences of Human Loss of N-Glycolylneuraminic Acid. Chembiochem, 18, 1155-1171.

- Orange, J.S.; Hossny, E.M.; Weiler, C.R.; Ballow, M.; Berger, M.; Bonilla, F.A.; Buckley, R.; Chinen, J.; Elgamal, Y.; Mazer, B.D.; et al. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin in human disease: A review of evidence by members of the Primary Immunodeficiency Committee of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, S525–S553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padler-Karavani, V.; Yu, H.; Cao, H.; Chokhawala, H.; Karp, F.; Varki, N.; Chen, X.; Varki, A. Diversity in specificity, abundance, and composition of anti-Neu5Gc antibodies in normal humans: Potential implications for disease. Glycobiology 2008, 18, 818–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parenti, G.; Pignata, C.; Vajro, P.; Salerno, M. New strategies for the treatment of lysosomal storage diseases (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 31, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parini, R.; Deodato, F. Intravenous Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Mucopolysaccharidoses: Clinical Effectiveness and Limitations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.I.; Manzella, S.M.; Baenziger, J.U. Rapid Clearance of Sialylated Glycoproteins by the Asialoglycoprotein Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 4597–4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PARK, E. I. , MI, Y., UNVERZAGT, C., GABIUS, H. J. & BAENZIGER, J. U. 2005. The asialoglycoprotein receptor clears glycoconjugates terminating with sialic acid alpha 2,6GalNAc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 102, 17125-9.

- Park, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y.K.; Kim, W.; You, S.K.; Do, J.; Jang, Y.; Oh, D.-B.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, H.H. Four unreported types of glycans containing mannose-6-phosphate are heterogeneously attached at three sites (including newly found Asn 233) to recombinant human acid alpha-glucosidase that is the only approved treatment for Pompe disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 2418–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacco, E.; Paul, A.; Segal, D. Glycans to improve efficacy and solubility of protein aggregation inhibitors. Neural Regen. Res. 2021, 16, 2215–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavelić, K.; Kolak, T.; Kapitanović, S.; Radošević, S.; Spaventi. ; Krušlin, B.; Pavelić, J. Gastric cancer: the role of insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF 2) and its receptors (IGF 1R and M6-P/IGF 2R). J. Pathol. 2003, 201, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelaia, C.; Calabrese, C.; Vatrella, A.; Busceti, M.T.; Garofalo, E.; Lombardo, N.; Terracciano, R.; Pelaia, G. Benralizumab: From the Basic Mechanism of Action to the Potential Use in the Biological Therapy of Severe Eosinophilic Asthma. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, N.A.; Chan, K.F.; Lin, P.C.; Song, Z. The “less-is-more” in therapeutic antibodies: Afucosylated anti-cancer antibodies with enhanced antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. mAbs 2018, 10, 693–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PERLMAN, S. , VAN DEN HAZEL, B., CHRISTIANSEN, J., GRAM-NIELSEN, S., JEPPESEN, C. B., ANDERSEN, K. V., HALKIER, T., OKKELS, S. & SCHAMBYE, H. T. 2003. Glycosylation of an N-terminal extension prolongs the half-life and increases the in vivo activity of follicle stimulating hormone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 88, 3227-35.

- Peschke, B.; Keller, C.W.; Weber, P.; Quast, I.; Lünemann, J.D. Fc-Galactosylation of Human Immunoglobulin Gamma Isotypes Improves C1q Binding and Enhances Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 646–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, N.B.; Meng, W.S. Protein aggregation and immunogenicity of biotherapeutics. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 585, 119523–119523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PORTER, S. 2001. Human immune response to recombinant human proteins. J Pharm Sci, 90, 1-11.

- Pound, J.D.; Lund, J.; Jefferis, R. Aglycosylated chimaeric human IgG3 can trigger the human phagocyte respiratory burst. Mol. Immunol. 1993, 30, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, K.P.; Thompson, A.R. B-Cell and T-Cell Epitopes in Anti-factor VIII Immune Responses. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2009, 37, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Liu, T.; Yang, L.; Daus, A.; Crowley, R.; Zhou, Q. Structural characterization of N-linked oligosaccharides on monoclonal antibody cetuximab by the combination of orthogonal matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization hybrid quadrupole–quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry and sequential enzymatic digestion. Anal. Biochem. 2007, 364, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinowitz, J.E.; Rolling, F.; Li, C.; Conrath, H.; Xiao, W.; Xiao, X.; Samulski, R.J. Cross-Packaging of a Single Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Type 2 Vector Genome into Multiple AAV Serotypes Enables Transduction with Broad Specificity. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajeev, K.G.; Nair, J.K.; Jayaraman, M.; Charisse, K.; Taneja, N.; O'Shea, J.; Willoughby, J.L.S.; Yucius, K.; Nguyen, T.; Shulga-Morskaya, S.; et al. Hepatocyte-Specific Delivery of siRNAs Conjugated to Novel Non-nucleosidic Trivalent N-Acetylgalactosamine Elicits Robust Gene Silencing in Vivo. ChemBioChem 2015, 16, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, T.S. Terminal sugars of Fc glycans influence antibody effector functions of IgGs. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2008, 20, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, T.; Briggs, J.B.; Borge, S.M.; Jones, A.J.S. Species-specific variation in glycosylation of IgG: evidence for the species-specific sialylation and branch-specific galactosylation and importance for engineering recombinant glycoprotein therapeutics. Glycobiology 2000, 10, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, R.; Tharakaraman, K.; Sasisekharan, V.; Sasisekharan, R. Glycan–protein interactions in viral pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016, 40, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reily, C.; Stewart, T.J.; Renfrow, M.B.; Novak, J. Glycosylation in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rennke, H.G.; Cotran, R.S.; A Venkatachalam, M. Role of molecular charge in glomerular permeability. Tracer studies with cationized ferritins. J. Cell Biol. 1975, 67, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringe, R.P.; Pugach, P.; Cottrell, C.A.; LaBranche, C.C.; Seabright, G.E.; Ketas, T.J.; Ozorowski, G.; Kumar, S.; Schorcht, A.; van Gils, M.J.; et al. Closing and Opening Holes in the Glycan Shield of HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein SOSIP Trimers Can Redirect the Neutralizing Antibody Response to the Newly Unmasked Epitopes. J. Virol. 2019, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinis, N.; Golden, J.E.; Marceau, C.D.; Carette, J.E.; Van Zandt, M.C.; Gilmore, R.; Contessa, J.N. Editing N-Glycan Site Occupancy with Small-Molecule Oligosaccharyltransferase Inhibitors. Cell Chem. Biol. 2018, 25, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, D.; Brown, T.; Harper, R.; Pamarthi, M.; Nixon, J.; Bromirski, J.; Li, C.-M.; Ghali, R.; Xie, H.; Medvedeff, G.; et al. Production and characterization of a novel human recombinant alpha-1-antitrypsin in PER.C6 cells. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 162, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ROSSI, M. , PARENTI, G., DELLA CASA, R., ROMANO, A., MANSI, G., AGOVINO, T., ROSAPEPE, F., VOSA, C., DEL GIUDICE, E. & ANDRIA, G. 2007. Long-term enzyme replacement therapy for pompe disease with recombinant human alpha-glucosidase derived from chinese hamster ovary cells. J Child Neurol, 22, 565-73.

- Royo, F.; Cossio, U.; de Angulo, A.R.; Llop, J.; Falcon-Perez, J.M. Modification of the glycosylation of extracellular vesicles alters their biodistribution in mice. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 1531–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rujas, E.; Cui, H.; Sicard, T.; Semesi, A.; Julien, J.-P. Structural characterization of the ICOS/ICOS-L immune complex reveals high molecular mimicry by therapeutic antibodies. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RUNKEL, L. , MEIER, W., PEPINSKY, R. B., KARPUSAS, M., WHITTY, A., KIMBALL, K., BRICKELMAIER, M., MULDOWNEY, C., JONES, W. & GOELZ, S. E. 1998. Structural and functional differences between glycosylated and non-glycosylated forms of human interferon-beta (IFN-beta). Pharm Res, 15, 641-9.

- Rushworth, J.L.; Montgomery, K.S.; Cao, B.; Brown, R.; Dibb, N.J.; Nilsson, S.K.; Chiefari, J.; Fuchter, M.J. Glycosylated Nanoparticles Derived from RAFT Polymerization for Effective Drug Delivery to Macrophages. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 5775–5786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuraba, H.; Murata-Ohsawa, M.; Kawashima, I.; Tajima, Y.; Kotani, M.; Ohshima, T.; Chiba, Y.; Takashiba, M.; Jigami, Y.; Fukushige, T.; et al. Comparison of the effects of agalsidase alfa and agalsidase beta on cultured human Fabry fibroblasts and Fabry mice. J. Hum. Genet. 2005, 51, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salama, A.; Evanno, G.; Lim, N.; Rousse, J.; Le Berre, L.; Nicot, A.; Bach, J.-M.; Brouard, S.; Harris, K.M.; Ehlers, M.R.; et al. Anti-Gal and Anti-Neu5Gc Responses in Nonimmunosuppressed Patients After Treatment With Rabbit Antithymocyte Polyclonal IgGs. Transplantation 2017, 101, 2501–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallustio, S.; Stanley, P. Novel genetic instability associated with a developmental regulated glycosyltransferase locus in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 1989, 15, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallusto, F.; Lanzavecchia, A. Efficient Presentation of Soluble Antigen by Cultured Human Dendritic Cells Is Maintained by Granulocyte/Macrophage Colony-stimulating Factor Plus Interleukin 4 and Downregulated by Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SARENEVA, T. , PIRHONEN, J., CANTELL, K. & JULKUNEN, I. 1995. N-glycosylation of human interferon-gamma: glycans at Asn-25 are critical for protease resistance. Biochem J, 308 ( Pt 1), 9-14.

- SARMAY, G. , LUND, J., ROZSNYAY, Z., GERGELY, J. & JEFFERIS, R. 1992. Mapping and comparison of the interaction sites on the Fc region of IgG responsible for triggering antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) through different types of human Fc gamma receptor. Mol Immunol, 29, 633-9.

- SASAWATARI, S. , OKAMOTO, Y., KUMANOGOH, A. & TOYOFUKU, T. 2020. Blockade of N-Glycosylation Promotes Antitumor Immune Response of T Cells. J Immunol, 204, 1373-1385.

- Sato, Y.; Beutler, E. Binding, internalization, and degradation of mannose-terminated glucocerebrosidase by macrophages. J. Clin. Investig. 1993, 91, 1909–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazinsky, S.L.; Ott, R.G.; Silver, N.W.; Tidor, B.; Ravetch, J.V.; Wittrup, K.D. Aglycosylated immunoglobulin G1variants productively engage activating Fc receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 20167–20172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCHACHTER, H. 2000. The joys of HexNAc. The synthesis and function of N- and O-glycan branches. Glycoconj J, 17, 465-83.

- SCHIFFMANN, R. , KOPP, J. B., AUSTIN, H. A., 3RD, SABNIS, S., MOORE, D. F., WEIBEL, T., BALOW, J. E. & BRADY, R. O. 2001. Enzyme replacement therapy in Fabry disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 285, 2743-9.

- Schiffmann, R.; Murray, G.J.; Treco, D.; Daniel, P.; Sellos-Moura, M.; Myers, M.; Quirk, J.M.; Zirzow, G.C.; Borowski, M.; Loveday, K.; et al. Infusion of α-galactosidase A reduces tissue globotriaosylceramide storage in patients with Fabry disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000, 97, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SCHLESINGER, P. H. , DOEBBER, T. W., MANDELL, B. F., WHITE, R., DESCHRYVER, C., RODMAN, J. S., MILLER, M. J. & STAHL, P. 1978. Plasma clearance of glycoproteins with terminal mannose and N-acetylglucosamine by liver non-parenchymal cells. Studies with beta-glucuronidase, N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase, ribonuclease B and agalacto-orosomucoid. Biochem J, 176, 103-9.

- Schroeder, H.W., Jr.; Cavacini, L. Structure and function of immunoglobulins. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125 (Suppl. 2), S41–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SCHWAB, I. & NIMMERJAHN, F. 2013. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy: how does IgG modulate the immune system? Nat Rev Immunol, 13, 176-89.

- SEITE, J. F. , SHOENFELD, Y., YOUINOU, P. & HILLION, S. 2008. What is the contents of the magic draft IVIg? Autoimmun Rev, 7, 435-9.

- Seo, J.; Oh, D.-B. Mannose-6-phosphate glycan for lysosomal targeting: various applications from enzyme replacement therapy to lysosome-targeting chimeras. Anim. Cells Syst. 2022, 26, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SHAALTIEL, Y. , BARTFELD, D., HASHMUELI, S., BAUM, G., BRILL-ALMON, E., GALILI, G., DYM, O., BOLDIN-ADAMSKY, S. A., SILMAN, I., SUSSMAN, J. L., FUTERMAN, A. H. & AVIEZER, D. 2007. Production of glucocerebrosidase with terminal mannose glycans for enzyme replacement therapy of Gaucher's disease using a plant cell system. Plant Biotechnol J, 5, 579-90.

- Shamie, I.; Duttke, S.H.; Karottki, K.J.l.C.; Han, C.Z.; Hansen, A.H.; Hefzi, H.; Xiong, K.; Li, S.; Roth, S.J.; Tao, J.; et al. A Chinese hamster transcription start site atlas that enables targeted editing of CHO cells. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2021, 3, lqab061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Li, C.-W.; Lim, S.-O.; Sun, L.; Lai, Y.-J.; Hou, J.; Liu, C.; Chang, C.-W.; Qiu, Y.; Hsu, J.-M.; et al. Deglycosylation of PD-L1 by 2-deoxyglucose reverses PARP inhibitor-induced immunosuppression in triple-negative breast cancer. 2018, 8, 1837–+.

- Sharma, V.K.; Osborn, M.F.; Hassler, M.R.; Echeverria, D.; Ly, S.; Ulashchik, E.A.; Martynenko-Makaev, Y.V.; Shmanai, V.V.; Zatsepin, T.S.; Khvorova, A.; et al. Novel Cluster and Monomer-Based GalNAc Structures Induce Effective Uptake of siRNAs in Vitro and in Vivo. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29, 2478–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, D.; Kamen, A. Advancements in the design and scalable production of viral gene transfer vectors. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 115, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeley, D.M.; Merrill, B.M.; Taylor, L.C. Characterization of Monoclonal Antibody Glycosylation: Comparison of Expression Systems and Identification of Terminal α-Linked Galactose. Anal. Biochem. 1997, 247, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Bryant, K.D.; Brown, S.M.; Randell, S.H.; Asokan, A. Terminal N-Linked Galactose Is the Primary Receptor for Adeno-associated Virus 9. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 13532–13540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shental-Bechor, D.; Levy, Y. Effect of glycosylation on protein folding: A close look at thermodynamic stabilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 8256–8261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, V.L.; Campbell, E.J.; Senior, R.M.; Stahl, P.D. Characterization of the mannose/fucose receptor on human mononuclear phagocytes. . 1982, 32, 423–31. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.H.; Goudar, C.T. Recent advances in the understanding of biological implications and modulation methodologies of monoclonal antibody N-linked high mannose glycans. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2014, 111, 1907–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, D.; Li, F.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Xuan, Y.; Ping, Y.; Zhang, Y. Targeting glycosylation of PD-1 to enhance CAR-T cell cytotoxicity. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHIELDS, R. L. , LAI, J., KECK, R., O'CONNELL, L. Y., HONG, K., MENG, Y. G., WEIKERT, S. H. & PRESTA, L. G. 2002. Lack of fucose on human IgG1 N-linked oligosaccharide improves binding to human Fcgamma RIII and antibody-dependent cellular toxicity. J Biol Chem, 277, 26733-40.

- Shinkawa, T.; Nakamura, K.; Yamane, N.; Shoji-Hosaka, E.; Kanda, Y.; Sakurada, M.; Uchida, K.; Anazawa, H.; Satoh, M.; Yamasaki, M.; et al. The Absence of Fucose but Not the Presence of Galactose or Bisecting N-Acetylglucosamine of Human IgG1 Complex-type Oligosaccharides Shows the Critical Role of Enhancing Antibody-dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 3466–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitara, K. Potelligent Antibodies as Next Generation Therapeutic Antibodies. YAKUGAKU ZASSHI 2009, 129, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.M.; Elliott, S. Glycoengineering: The effect of glycosylation on the properties of therapeutic proteins. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 94, 1626–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sly, W.S. Receptor-mediated transport of acid hydrolases to lysosomes. Curr. Top. Cell. Regul. 1985, 26, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, Y.; Lee, J.M.; Park, H.-R.; Jung, S.-C.; Park, T.H.; Oh, D.-B. Enhanced sialylation and in vivo efficacy of recombinant human α-galactosidase through in vitro glycosylation. BMB Rep. 2013, 46, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, Y.B.; Cho, S.Y.; Park, S.W.; Kim, S.J.; Ko, A.-R.; Kwon, E.-K.; Han, S.J.; Jin, D.-K. Phase I/II clinical trial of enzyme replacement therapy with idursulfase beta in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis II (Hunter Syndrome). Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013, 8, 42–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solá, R.J.; Griebenow, K. Influence of modulated structural dynamics on the kinetics of α-chymotrypsin catalysis. FEBS J. 2006, 273, 5303–5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solá, R.J.; Griebenow, K. Effects of glycosylation on the stability of protein pharmaceuticals. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 98, 1223–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solá, R.J.; Rodriguez-Martinez, J.A.; Griebenow, K. Modulation of protein biophysical properties by chemical glycosylation: biochemical insights and biomedical implications. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 2133–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondermann, P.; Pincetic, A.; Maamary, J.; Lammens, K.; Ravetch, J.V. General mechanism for modulating immunoglobulin effector function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, 9868–9872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, H.; Xue, Y.; Lu, X.; Bahar, I.; Kepp, O.; Hung, M.-C.; Kroemer, G.; Wan, Y. Pharmacologic Suppression of B7-H4 Glycosylation Restores Antitumor Immunity in Immune-Cold Breast Cancers. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1872–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahn, P.N.; Hansen, A.H.; Hansen, H.G.; Arnsdorf, J.; Kildegaard, H.F.; Lewis, N.E. A Markov chain model for N-linked protein glycosylation – towards a low-parameter tool for model-driven glycoengineering. Metab. Eng. 2015, 33, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahn, P.N.; Hansen, A.H.; Kol, S.; Voldborg, B.G.; Lewis, N.E. Predictive glycoengineering of biosimilars using a Markov chain glycosylation model. Biotechnol. J. 2016, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, P.; Gordon, S. Expression of a mannosyl-fucosyl receptor for endocytosis on cultured primary macrophages and their hybrids. J. Cell Biol. 1982, 93, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, P.D. The Macrophage Mannose Receptor: Current Status. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1990, 2, 317–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, P.D. The mannose receptor and other macrophage lectins. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1992, 4, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, P.D.; Rodman, J.S.; Miller, M.J.; Schlesinger, P.H. Evidence for receptor-mediated binding of glycoproteins, glycoconjugates, and lysosomal glycosidases by alveolar macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1978, 75, 1399–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockert, R.J. The asialoglycoprotein receptor: relationships between structure, function, and expression. Physiol. Rev. 1995, 75, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, L.; Boi, S.; Guapo, F.; Donohue, N.; Barron, N.; Rainbow-Fletcher, A.; Bones, J. Proteomic Landscape of Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV)-Producing HEK293 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ströh, L.J.; Stehle, T. Glycan Engagement by Viruses: Receptor Switches and Specificity. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2014, 1, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Zhao, H.; Xia, H. Glycosylation-modified erythropoietin with improved half-life and biological activity. Int. J. Hematol. 2010, 91, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerford, C.; Samulski, R.J. Membrane-Associated Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan Is a Receptor for Adeno-Associated Virus Type 2 Virions. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 1438–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, C.-W.; Chung, E.M.; Yang, R.; Kim, Y.-S.; Park, A.H.; Lai, Y.-J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.-H.; Liu, J.; et al. Targeting Glycosylated PD-1 Induces Potent Antitumor Immunity. Cancer Res 2020, 80, 2298–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Kim, A.M.J.; Lim, S.-O. Glycosylation of Immune Receptors in Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Kim, A.M.J.; Murray, A.A.; Lim, S.-O. N-Glycosylation Facilitates 4-1BB Membrane Localization by Avoiding Its Multimerization. Cells 2022, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.-T.; Mayes, P.A.; Acharya, C.; Zhong, M.Y.; Cea, M.; Cagnetta, A.; Craigen, J.; Yates, J.; Gliddon, L.; Fieles, W.; et al. Novel anti–B-cell maturation antigen antibody-drug conjugate (GSK2857916) selectively induces killing of multiple myeloma. Blood 2014, 123, 3128–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Donovan, M.J.; Rogers, R.A.; Ezekowitz, R.A.B. Distribution of murine mannose receptor expression from early embryogenesis through to adulthood. Cell Tissue Res. 1998, 292, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tams, J.W.; Vind, J.; Welinder, K.G. Adapting protein solubility by glycosylation.: N-Glycosylation mutants of Coprinus cinereus peroxidase in salt and organic solutions. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Protein Struct. Mol. Enzym. 1999, 1432, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangvoranuntakul, P.; Gagneux, P.; Diaz, S.; Bardor, M.; Varki, N.; Varki, A.; Muchmore, E. Human uptake and incorporation of an immunogenic nonhuman dietary sialic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 12045–12050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.H.; Morrison, S.L. Studies of aglycosylated chimeric mouse-human IgG. Role of carbohydrate in the structure and effector functions mediated by the human IgG constant region. J. Immunol. 1989, 143, 2595–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, M.D.; Job, E.R.; Deng, Y.-M.; Gunalan, V.; Maurer-Stroh, S.; Reading, P.C. Playing Hide and Seek: How Glycosylation of the Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin Can Modulate the Immune Response to Infection. Viruses 2014, 6, 1294–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Drickamer, K. Structural requirements for high affinity binding of complex ligands by the macrophage mannose receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TEKOAH, Y. , TZABAN, S., KIZHNER, T., HAINRICHSON, M., GANTMAN, A., GOLEMBO, M., AVIEZER, D. & SHAALTIEL, Y. 2013. Glycosylation and functionality of recombinant beta-glucocerebrosidase from various production systems. Biosci Rep, 33.