Submitted:

02 March 2023

Posted:

03 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature review

2. Materials and Methods

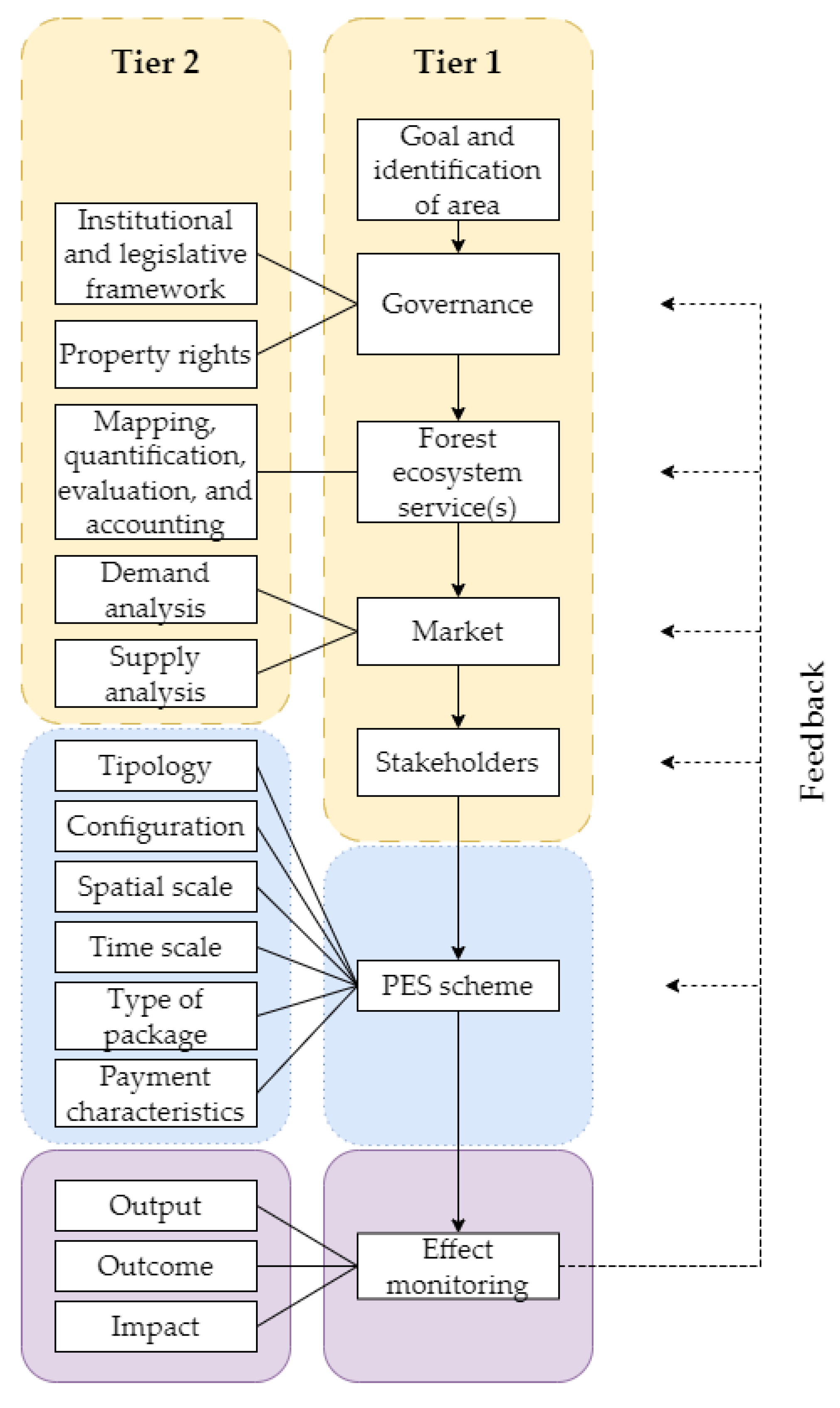

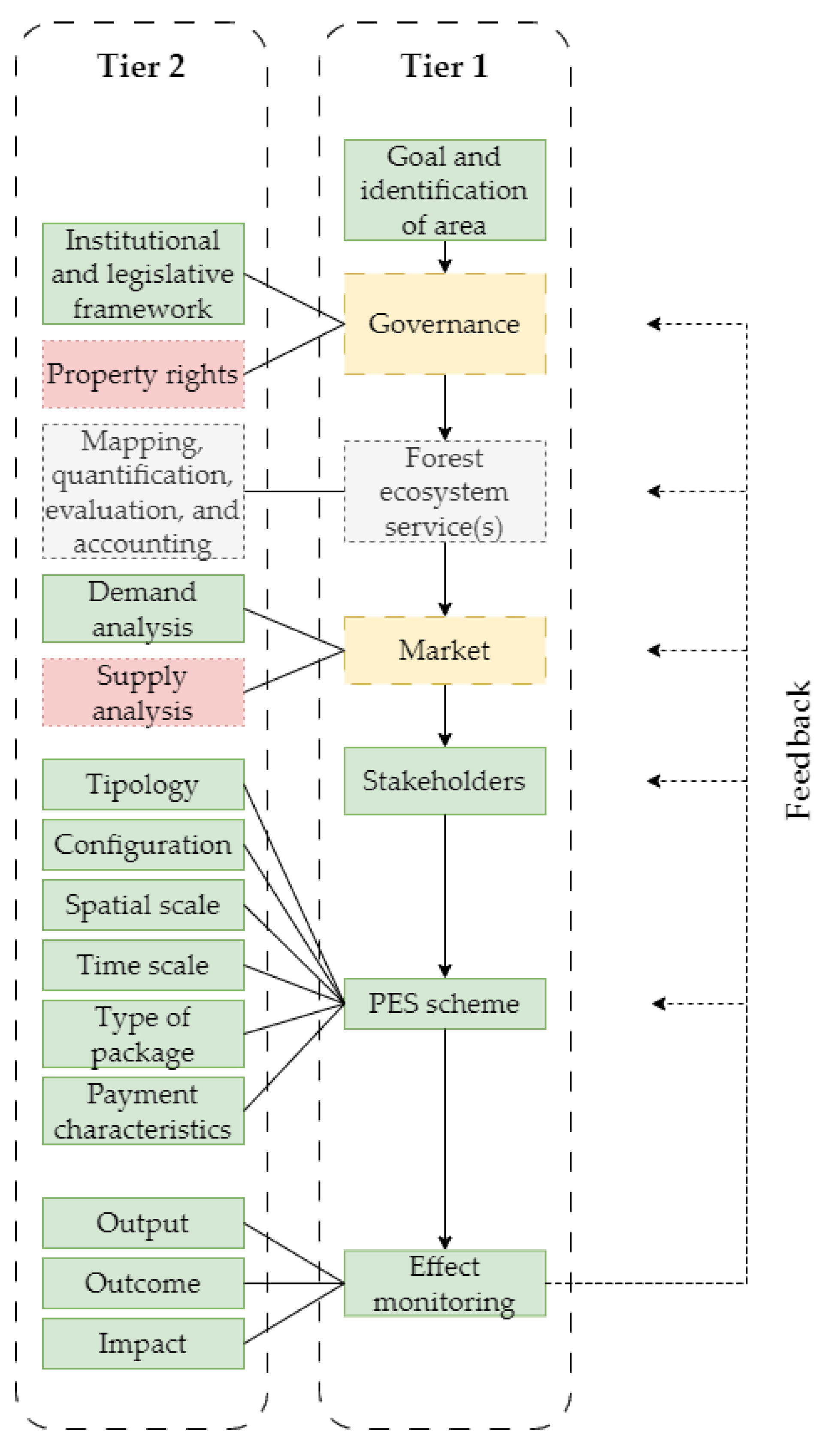

2.1. A solution-driven PES framework proposal: design, implementation and monitoring

2.1.1. Goal and identification area

- demand-driven: this is the case when service users encounter a problem in its provision and are willing to pay for its maintenance. For example, improving the quality and quantity of drinking water (off-site). In this case, service providers are incentivised to produce it.

- Supply-driven: this is found when there is a problem on-site, related to the conservation and management of the ecosystem. In this case, the economic contribution by the service users helps the provider to maintain or improve the management of the natural resource for the benefit of both the ecosystem and the users.

- Solution-driven: this occurs when a third-party organisation identifies cases where the creation of a PES scheme would be feasible, ideal, and beneficial.

2.1.2. Governance

- access and use: the possibility of choosing who can have access to and who to exclude on the land tenure for use.

- Control: the possibility of choosing for which use land tenure is to be used.

- Transfer: the possibility of transferring the right of access, use and control to other persons, by selling, mortgaging, or bequeathing the land tenure.

2.1.3. Forest ecosystem services

2.1.4. Market

2.1.5. Stakeholders

- service producers/sellers: the public or private land and forest owners who conserve and manage the natural resource.

- Service users/buyers: who are willing to pay for the provision of the service and may also be public or private.

- Intermediaries: who connect producers and users and who support the creation of the PES scheme, for example trade associations, public institutions, and NGOs. This category also includes donors, regulators who influence, control, and facilitate the start-up and effectiveness of PES and funding agencies that support the start-up and operation of the scheme with for example feasibility studies.

- Knowledge providers: those who provide advice, knowledge, and assistance for the development of the PES scheme, such as experts, planners, universities and research institutes and consultants.

2.1.6. PES scheme

- a single service provider and service user (one-to-one): such as the case of the government or a company that comes into direct contact with an individual forest or landowner [7];

- many service providers and a single service user (one-to-many): such as the case of Vittel with farmers in France [64];

- a single service provider and many service users (many-to-one): such as the case of the UK Ministry of Defence and retail companies and the North Pennines AONB with the UK Woodland Carbon Code in Cumbria [65];

- many service providers and service users (many-to-many): such as the case of water certificates issued by the Bonneville Environmental Foundation between private sector businesses and landowners in the USA [66].

- source: whether it is public, private or mixed;

- mode: whether it is based on improved management practices (input-based) or on the actual provision of the ecosystem service (output-based);

- type: whether it is cash, in-kind or mixed;

- time: whether it occurs one-off, whether periodic or mixed;

- frequency: whether it occurs upfront, after practice improvement or after service delivery.

2.1.7. Effect monitoring

2.2. Case study

2.3. Data collection

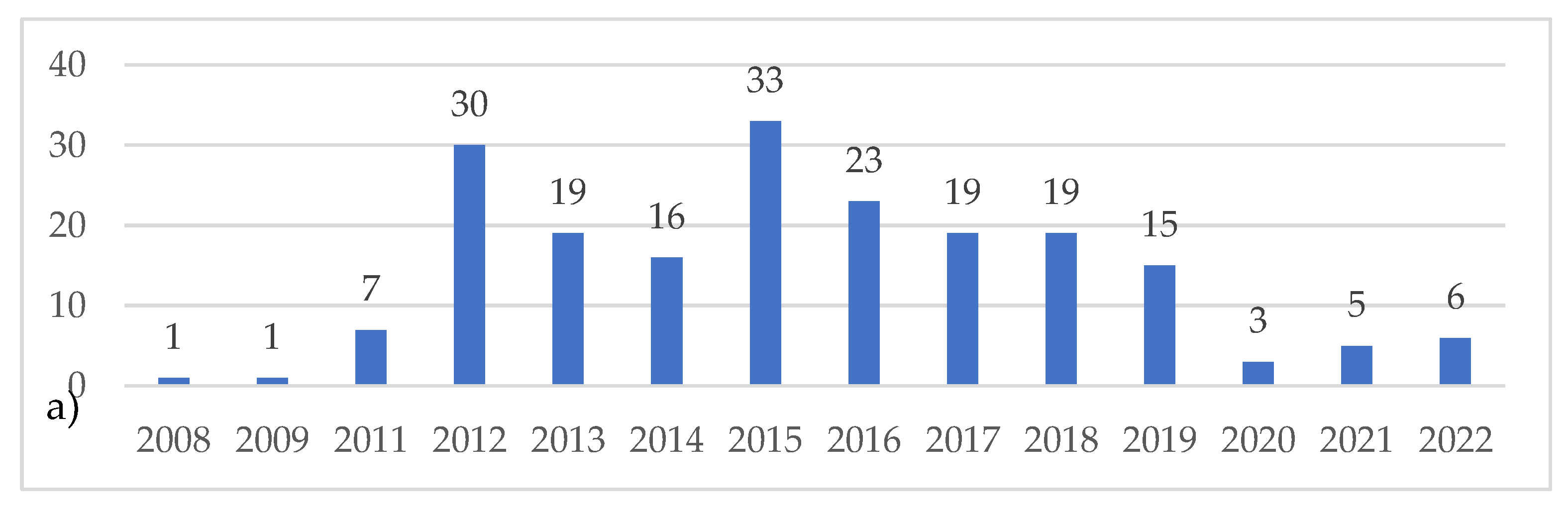

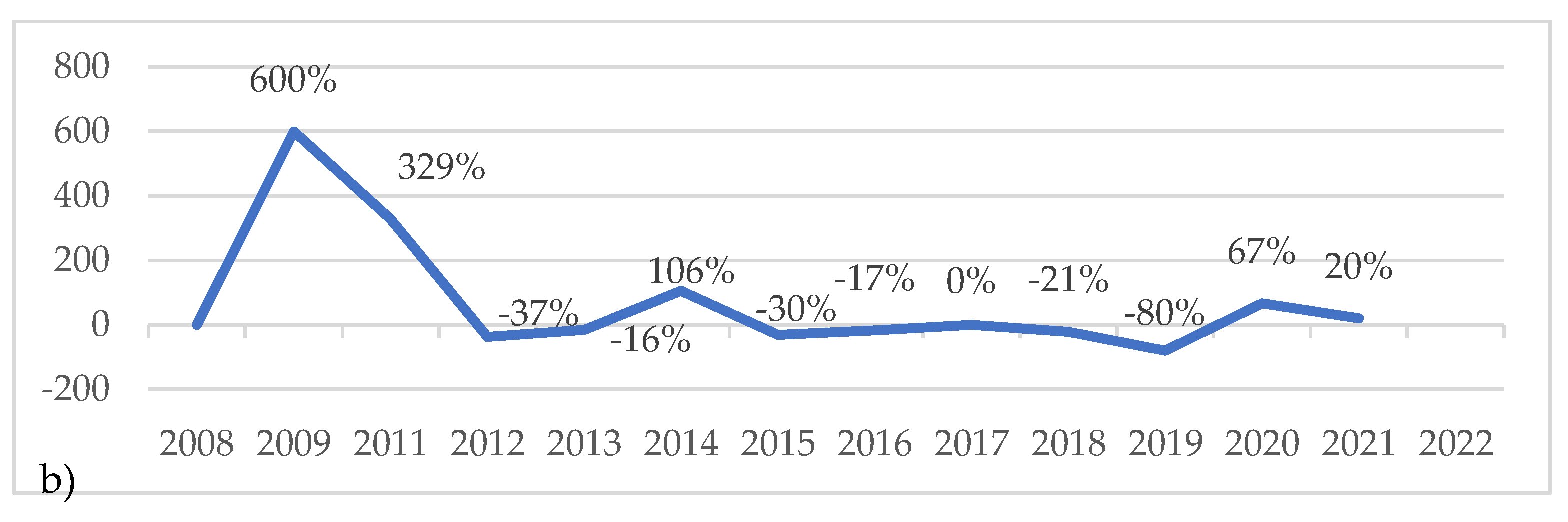

2.3.1. Data mining

2.3.2. Document review

2.3.3. Semi-structured interviews

2.4. Data analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

-

Gender:

- Male

- Female

-

Age:

- 6-17

- 18-30

- 31-45

- 46-60

- >60

-

Level of education:

- Completed primary education

- Skilled worker

- Completed secondary education

- Bachelor/Master’s degree

- PhD degree

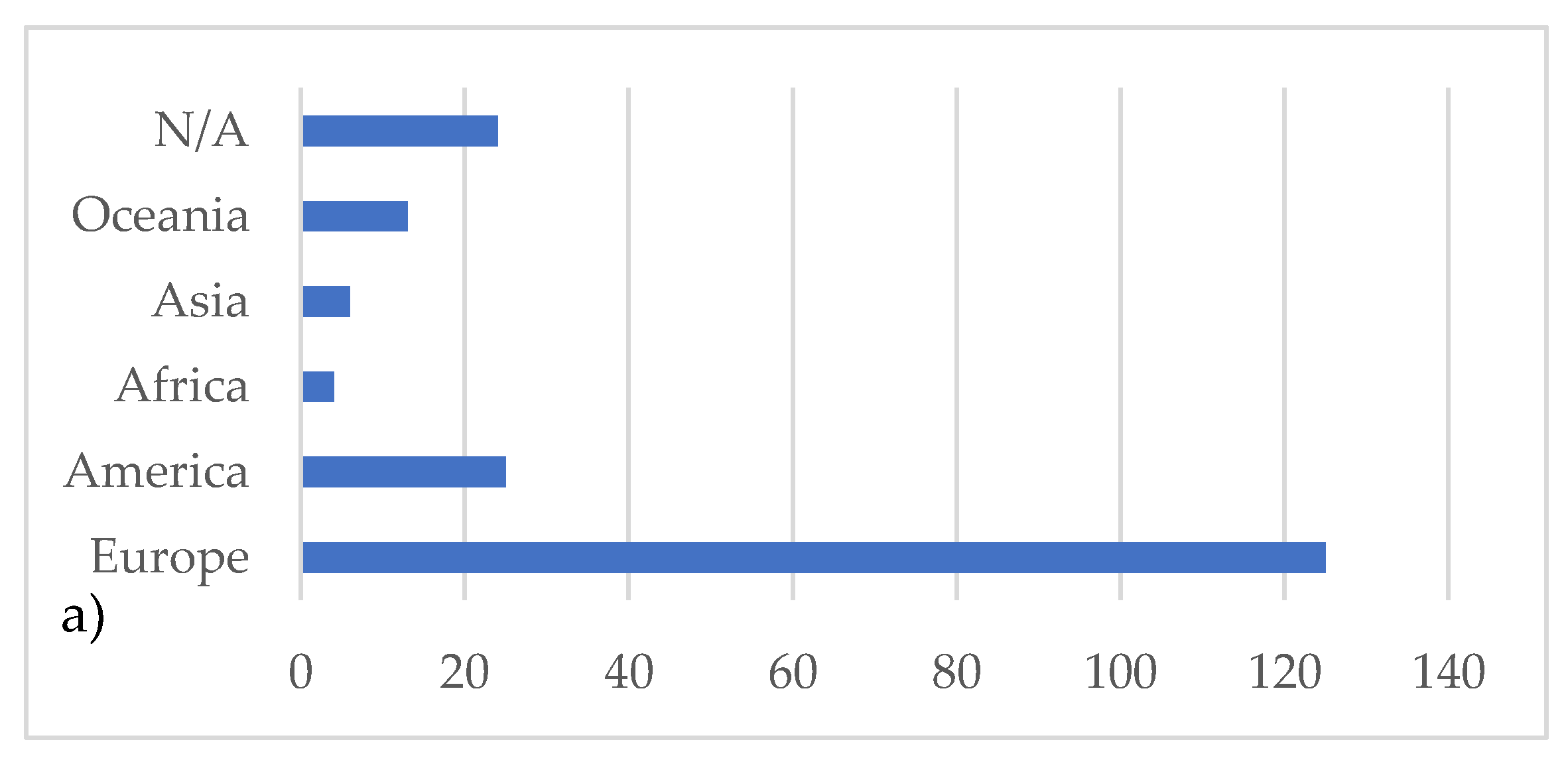

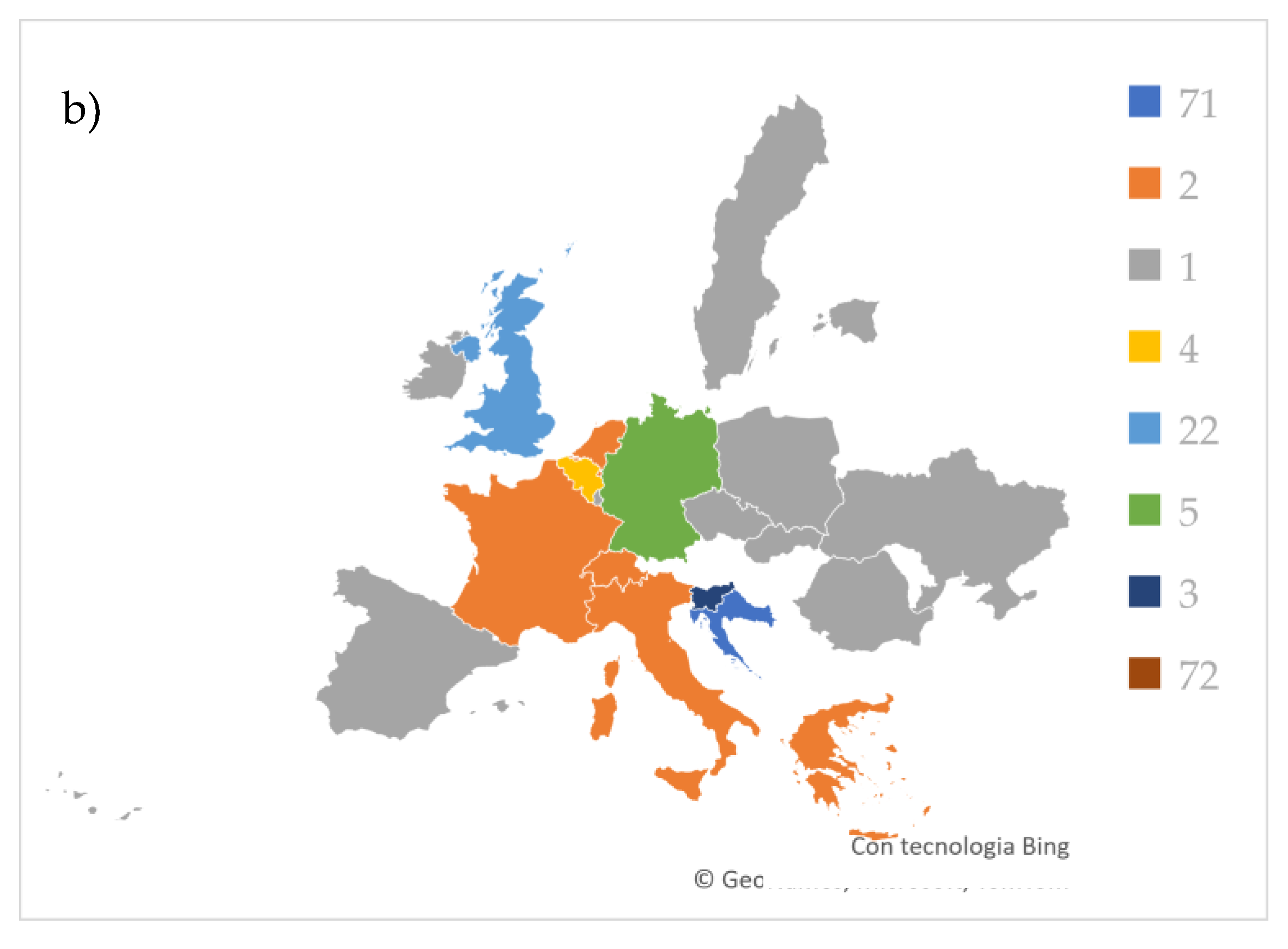

- Where do you come from?

-

Do you know what eco system services are?

- Yes

- No

- If yes, can you mention some of them?

-

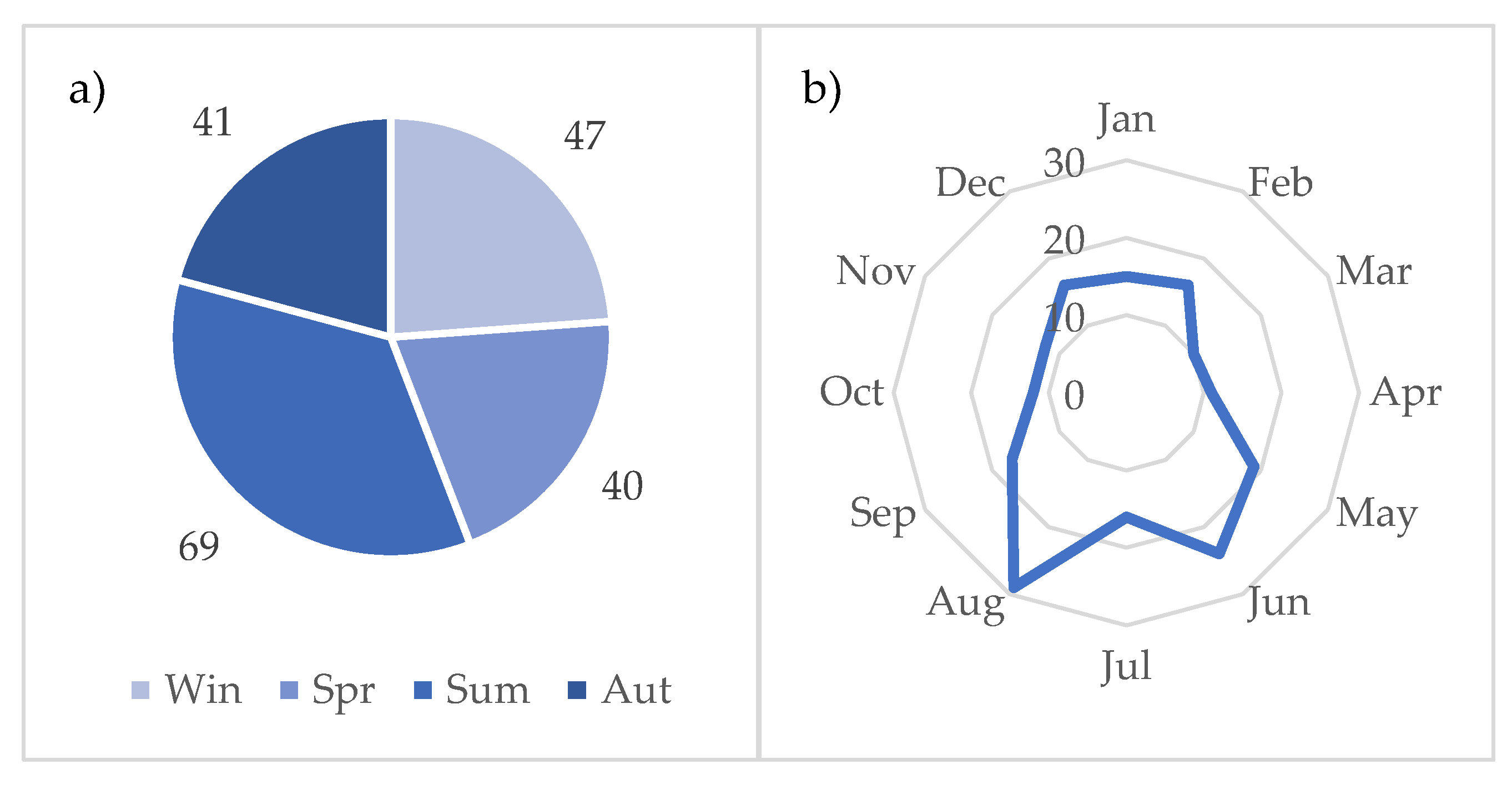

How often do you visit Medvednica?

- First time

- Once a year

- Several times a year

- Once a month

- Several times a month

- Once a week

- Several times a week

-

Did you go up and down walking?

- Yes

- No

- If no, how long are you walking?

-

How often and how intensively do you exercise?

- Once a month - Light activity

- Several times a month - Moderate activity

- Once a week - Intense activity

- Several times a week

-

How much does the visit of Medvednica impact the following areas? (1 – Completely disagree, 2 – Partially disagree, 3 – Neither agree nor disagree, 4 – Partially agree, 5 – Completely agree)

-

Improvement of social well-being

- 1 2 3 4 5

-

Improvement of psychological well-being

- 1 2 3 4 5

-

Improvement of physical well-being

- 1 2 3 4 5

-

-

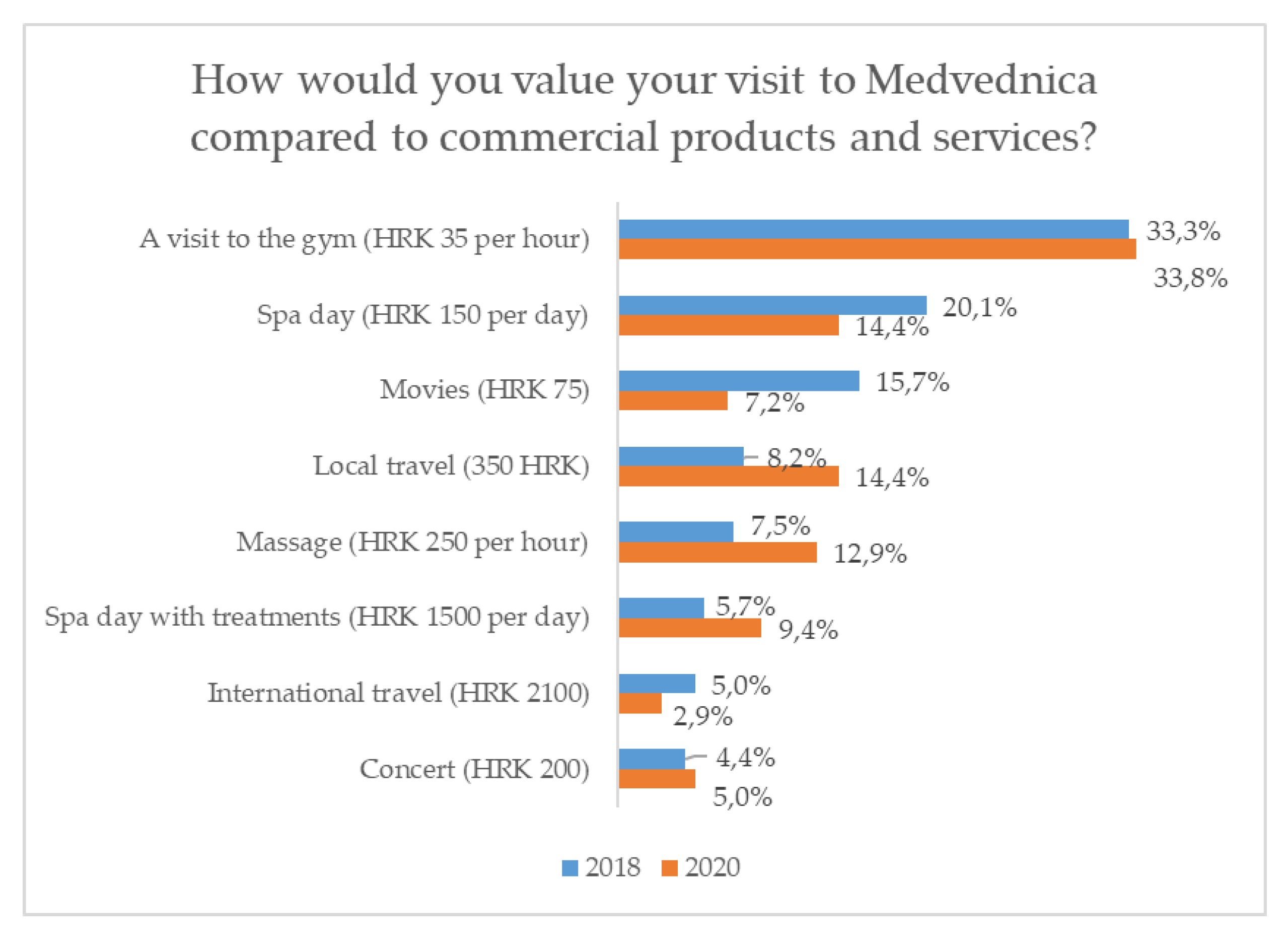

How would you value your visit to Medvednica compared to commercial products and services?

- A visit to the gym (HRK 35 per hour)

- Movies (HRK 75)

- Spa day (HRK 150 per day)

- Massage (HRK 250 per hour)

- Spa day with treatments (HRK 1500 per day)

- Concert (HRK 200)

- Local travel (HRK 350)

- International travel (HRK 2100)

-

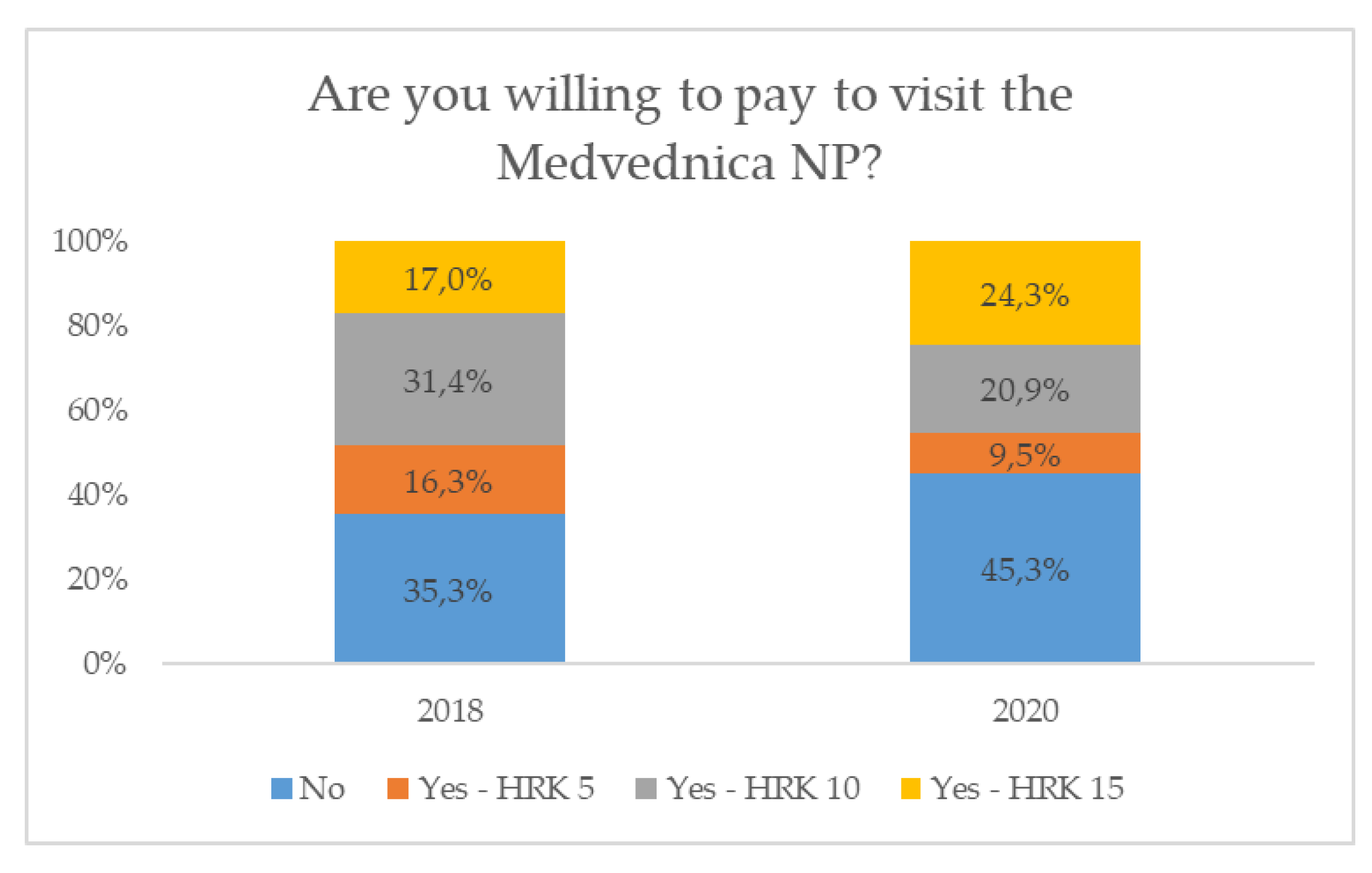

Are you willing to pay to visit the Medvednica Nature Park?

- Yes

- No

- If yes, how much?

- 5 kn

- 10 kn

- 15 kn

Appendix B

- 12.

-

About the project

- What was your role in developing research project and carrying it forward?

- Are there any other PES projects that have helped you in co-designing the project? Which are these and why?

- 13.

-

About the co-design process

- What was your main emotion during the co-design (enthusiasm, sense of participation, conflictual, affliction, etc.)?

- 14.

-

About PES

- What element(s) do you think are necessary for the successful implementation of a PES?

- What are the main difficulties/obstacles you found in the implementation of a PES?

- 15.

-

Future recommendations

- What is your perception of the added value/impact of the project implementation?

References

- Bruzzese, S.; Blanc, S.; Paletto, A.; Brun, F. A Systematic Review of Markets for Forest Ecosystem Services at an International Level. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 2023, 1–30, accepted.

- Tyrväinen, L.; Mäntymaa, E.; Juutinen, A.; Kurttila, M.; Ovaskainen, V. Private Landowners’ Preferences for Trading Forest Landscape and Recreational Values: A Choice Experiment Application in Kuusamo, Finland. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, A.; Herrera, D.; Leslie, G.; Pietracci, B.; Lubowski, R. A Real Options Framework for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation: Reconciling Short-Term Incentives with Long-Term Benefits from Conservation and Agricultural Intensification. Ecosystem Services 2021, 49, 101275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G.; Fratini, R.; Marone, E.; Sacchelli, S. A Spatial-Based Tool for the Analysis of Payments for Forest Ecosystem Services Related to Hydrogeological Protection. Forest Policy and Economics 2020, 111, 102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. Revisiting the Concept of Payments for Environmental Services. Ecological Economics 2015, 117, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S. Payments for Environmental Services: Some Nuts and Bolts. Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) Occasional Paper 2005, 32.

- Smith, S.; Rowcroft, P.; Everard, M.; Coludrick, L.; Reed, M.; Rogers, H.; Quick, T.; Eves, C.; White, C. Payments for Ecosystem Services: A Best Practice Guide; Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA): London, UK, 2013; p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- AA.VV. RaF Italy 2017-2018 - Report on the State of Forests and the Forestry Sector in Italy (Original Version: RaF Italia 2017-2018 - Rapporto Sullo Stato Delle Foreste e Del Settore Forestale in Italia); Compagnia delle Foreste: Arezzo, Italy, 2019; p. 282.

- Liu, D.; Hu, Z.T.; Jin, L.S. Review on analytical framework of eco-compensation. Shengtai Xuebao 2018, 38, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber-Stearns, H.R.; Bennett, D.E.; Posner, S.; Richards, R.C.; Fair, J.H.; Cousins, S.J.M.; Romulo, C.L. Social-Ecological Enabling Conditions for Payments for Ecosystem Services. Ecology and Society 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, S. The Devil in the Detail: A Practical Guide on Designing Payments for Environmental Services. International Review of Environmental and Resource Economics 2016, 9, 131–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconi, L. Redefining Payments for Environmental Services. Ecological Economics 2012, 73, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R.; Corbera, E.; Pascual, U.; Kosoy, N.; May, P.H. Reconciling Theory and Practice: An Alternative Conceptual Framework for Understanding Payments for Environmental Services. Ecological Economics 2010, 69, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, I.; Grieg-Gran, M.; Neves, N. All That Glitters: A Review of Payments for Watershed Services in Developing Countries; Natural Resource; International Institute for Environment and Development.; IIED: London, UK, 2008; ISBN 978-1-84369-653-7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Liu, H.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yu, P.; Yan, D. A PES Framework Coupling Socioeconomic and Ecosystem Dynamics from a Sustainable Development Perspective. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 329, 117043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G.; Ryan, C.; Fisher, J.; Corbera, E. In Defence of Simplified PES Designs. Nature Sustainability 2020, 3, 426–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, A.; Woodward, R.T. User Financing in a National Payments for Environmental Services Program: Costa Rican Hydropower. Ecological Economics 2010, 69, 1626–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, S.I.; Mota da Silva, J.; Ponette-González, A.G.; Silva, M.L.N.; da Rocha, H.R. Modeling the On-Site and off-Site Benefits of Atlantic Forest Conservation in a Brazilian Watershed. Ecosystem Services 2021, 48, 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selfa, T.; Urcuqui-Bustamante, A.M.; Cordoba, D.; Avila-Foucat, V.S.; Pischke, E.C.; Jones, K.W.; Nava-Lopez, M.Z.; Torrez, D.M. The Role of Situated Knowledge and Values in Reshaping Payment for Hydrological Services Programs in Veracruz, Mexico: An Actor-Oriented Approach. Journal of Rural Studies 2022, 95, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.; Nguyen, T.D.; Dao, C.T.L.; Hoang, L.T.; Pham, L.H.; Nguyen, L.T.; Tran, B.K. Impacts of Payment for Forest Environmental Services in Cat Tien National Park. Forests 2021, 12, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rossi, G.; Hecht, J.S.; Zia, A. A Mixed-Methods Analysis for Improving Farmer Participation in Agri-Environmental Payments for Ecosystem Services in Vermont, USA. Ecosystem Services 2021, 47, 101223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartczak, A.; Metelska-Szaniawska, K. Should We Pay, and to Whom, for Biodiversity Enhancement in Private Forests? An Empirical Study of Attitudes towards Payments for Forest Ecosystem Services in Poland. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, J.; Hokajärvi, R.; Hujala, T.; Kurttila, M. Ex Ante Evaluation of a PES System: Safeguarding Recreational Environments for Nature-Based Tourism. Journal of Rural Studies 2017, 52, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Börner, J.; Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Feder, S.; Pagiola, S. Payments for Environmental Services: Past Performance and Pending Potentials. Annual Review of Resource Economics 2020, 12, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snilsveit, B.; Stevenson, J.; Langer, L.; Tannous, N.; Ravat, Z.; Nduku, P.; Polanin, J.; Shemilt, I.; Eyers, J.; Ferraro, P.J. Incentives for Climate Mitigation in the Land Use Sector—the Effects of Payment for Environmental Services on Environmental and Socioeconomic Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2019, 15, e1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomeu, A.; Shukla, A.; Shukla, S.; Kiker, G.; Wu, C.-L.; Hendricks, G.S.; Boughton, E.H.; Sishodia, R.; Guzha, A.C.; Swain, H.M.; et al. Using Biodiversity Response for Prioritizing Participants and Service Provisions in a Payment-for-Water-Storage Program in the Everglades Basin. Journal of Hydrology 2022, 609, 127618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Báliková, K.; De Meo, I. Opinions towards the Water-related Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) Schemes: The Stakeholders’ Point of View. Water and Environment Journal 2021, 35, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, A.; Rannestad, M.M.; Hofstad, O. Conditional Payments for Carbon Sequestration as a Local Trading Game — A Case Study from a Tanzanian Village. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 240, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.; Hussain, M.; Ali, A.; Rehman, F.; Tabassum, A.; Amin, M.; Usman, N.; Bashir, S.; Raza, G.; Yousaf, A.; et al. Economic Valuation of Selected Ecosystem Services in Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT), Pakistan. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2022, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrväinen, L.; Silvennoinen, H.; Hallikainen, V. Effect of the Season and Forest Management on the Visual Quality of the Nature-Based Tourism Environment: A Case from Finnish Lapland. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 2017, 32, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viszlai, I.; Barred, J.I. San-Miguel_Ayanz Payments for Forest Ecosystem Services - SWOT Analysis and Possibilities for Implementation. EUR 28128 EN 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, H. Payments for Ecosystem Services; Defra Evidence and Analysis Series; Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA): London, UK, 2011; p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- Cavelier, J.; Munro Gay, I. Payment for Ecosystem Services; Global Environment Facility (GEF): Washington D.C., USA, 2012; p. 22.

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Forests and Water Valuation and Payments for Forest Ecosystem Services; United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-92-1-117175-4.

- Fripp, E. Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES): A Practical Guide to Assessing the Feasibility of PES Projects; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bagor, Indonesia, 2014; ISBN 978-602-1504-57-4. [Google Scholar]

- FAO Payments for Ecosystem Services and Food Security; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2011; ISBN 978-92-5-106796-3.

- Herbert, T.; Vonada, R.; Jenkins, M.; Byon, R.; Frausto Leyva, J.M. Environmental Funds and Payments for Ecosystems Services: RedLAC Capacity Building Project for Environmental Funds; The Latin America and Caribbean Network of Environmental Funds – RedLAC: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2010; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- Rankine, H.; Watkins, M.; Barnwal, P. Innovative Socio-Economic Policy for Improving Environmental Performance: Payments for Ecosystem Services; United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Paci c (UN ESCAP): Bangkok, Thailand, 2009; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Mayrand, K.; Paquin, M. Payments for Environmental Services: A Survey and Assessment of Current Schemes; Unisféra International Centre: Montreal, Canada, 2004; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, B.K.; Kousky, C.; Sims, K.R.E. Designing Payments for Ecosystem Services: Lessons from Previous Experience with Incentive-Based Mechanisms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 9465–9470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagiola, S.; Rios, A.R.; Arcenas, A. Can the Poor Participate in Payments for Environmental Services? Lessons from the Silvopastoral Project in Nicaragua. Environment and Development Economics 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, G.; Ridoutt, B.; Creeper, D.; Bellotti, B. A Framework for Assessing Local PES Proposals. Land Use Policy 2015, 43, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Brouwer, R.; Engel, S.; Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Muradian, R.; Pascual, U.; Pinto, R. From Principles to Practice in Paying for Nature’s Services. Nature Sustainability 2018, 1, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Fu, B.; Wang, S.; Wei, Y. Integrating Multiple Influencing Factors in Evaluating the Socioeconomic Effects of Payments for Ecosystem Services. Ecosystem Services 2021, 51, 101348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, S.; Fu, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, Y. Pathways from Payments for Ecosystem Services Program to Socioeconomic Outcomes. Ecosystem Services 2019, 39, 101005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Corbera, E.; Lapeyre, R. Payments for Environmental Services and Motivation Crowding: Towards a Conceptual Framework. Ecological Economics 2019, 156, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurttila, M.; Mäntymaa, E.; Tyrväinen, L.; Juutinen, A.; Hujala, T. Multi-Criteria Analysis Process for Creation and Evaluation of PES Alternatives in the Ruka-Kuusamo Tourism Area. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2020, 63, 1857–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, J.; Ollikainen, M. A PES Scheme Promoting Forest Biodiversity and Carbon Sequestration. Forest Policy and Economics 2022, 136, 102692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Wunder, S.; Ruiz-Pérez, M.; Moreno-Sanchez, R. del P. Global Patterns in the Implementation of Payments for Environmental Services. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0149847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Börner, J.; Baylis, K.; Corbera, E.; Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Ferraro, P.J.; Honey-Rosés, J.; Lapeyre, R.; Persson, U.M.; Wunder, S. Emerging Evidence on the Effectiveness of Tropical Forest Conservation. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0159152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samii, C.; Lisiecki, M.; Kulkarni, P.; Paler, L.; Chavis, L.; Snilstveit, B.; Vojtkova, M.; Gallagher, E. Effects of Payment for Environmental Services (PES) on Deforestation and Poverty in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2014, 10, 1–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Boag, G. Designing Payments for Ecosystem Services Schemes: Some Considerations. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2013, 5, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gios, G.; Rizio, D. Payment for Forest Environmental Services: A Meta-Analysis of Successful Elements. iForest - Biogeosciences and Forestry 2013, 6, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiber, T. Payments for Ecosystem Services: Legal and Institutional Frameworks; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2009; ISBN 978-2-8317-1176-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzese, S.; Ahmed, W.; Blanc, S.; Brun, F. Ecosystem Services: A Social and Semantic Network Analysis of Public Opinion on Twitter. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 15012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergiacomi, C.; Vuletić, D.; Paletto, A.; Barbierato, E.; Fagarazzi, C. Exploring National Park Visitors’ Judgements from Social Media: The Case Study of Plitvice Lakes National Park. Forests 2022, 13, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbierato, E.; Bernetti, I.; Capecchi, I. Analyzing TripAdvisor Reviews of Wine Tours: An Approach Based on Text Mining and Sentiment Analysis. International Journal of Wine Business Research 2021, 34, 212–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Europe Valuation and Payments for Forest Ecosystem Services in the Pan-European Region. Final Report of the Forest Europe Expert Group on Valuation and Payments for Forest Ecosystem Services. Forest Europe, Bratislava; Liaison Unit Bratislava: Zvolen, Slovak Republic, 2019; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- FAO Land Tenure and Rural Development; FAO Land Tenure Studies; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002; ISBN 92-5-104846-0.

- Santos-Martin, F.; Viinikka, A.; Mononen, L.; Brander, L.; Vihervaara, P.; Liekens, I.; Potschin-Young, M. Creating an Operational Database for Ecosystems Services Mapping and Assessment Methods. One Ecosystem 2018, 3, e26719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzese, S.; Blanc, S.; Brun, F. The Decision Trees Method to Support the Choice of Economic Evaluation Procedure: The Case of Protection Forests. Forest Science 2023, fxac062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations System of Environmental-Economic Accounting—Ecosystem Accounting: Final Draft; United Nations: New York, USA, 2021; p. 350.

- Matzdorf, B.; Sattler, C.; Engel, S.; Matzdorf, B.; Sattler, C.; Engel, S. Institutional Frameworks and Governance Structures of PES Schemes. Forest Policy and Economics 2013, Complete, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot-Maître, D. The Vittel Payments for Ecosystem Services: A “Perfect” PES Case? International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2006; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- AA VV. Woodland Carbon Code Requirements for Voluntary Carbon Sequestration Projects; The National Archives: London, UK, 2022; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Bonneville Environmental Foundation Water Restoration Certificates. Available online: https://www.b-e-f.org/programs/water-restoration-certificates/ (accessed on 26 February 2023).

- Lippi, A. The evaluation of public policies (original version: La valutazione delle politiche pubbliche); Il Mulino: Bologna, italy, 2007; ISBN 978-88-15-11638-3. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C.H. How Can Theory-Based Evaluation Make Greater Headway? Evaluation Review 1997, 21, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisma, S.; Boromisa, A.-M.; Farkas, A.; Tolic, I. Socio-Economic Evaluations of Nature Protected Areas: Health First Effect. European Journal of Geography 2020, 11, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakarić, M.; Tomašić, F.; Zečić, Ž.; Beljan, K. Features of Private Forest Management in Protected Areas with Reference to Nature Park »Medvednica« (original version: Specifičnosti gospodarenja privatnim šumama u zaštićenim područjima s osvrtom na Park prirode Medvednica). Nova mehanizacija šumarstva 2021, 42, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B. Web Scraping. In Encyclopedia of Big Data; Schintler, L.A., McNeely, C.L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-3-319-32001-4. [Google Scholar]

- Croatian Parliament Statute of the Republic of Croatia (original version: Statute of Republci of Croatia); 1990.

- Croatian Parliament Forest Act (original version: Zakon o Šumama); 2018; p. 40.

- Croatian Parliament Environment Protection Act (original version: Zakon o zaštiti okoliša); 2019.

- SINCERE Understanding the Health Functions of Peri-Urban Forests in Protected Areas and Payment for Ecosystem Services Available online: https://sincereforests.eu/understanding-the-health-functions-of-peri-urban-forests-in-protected-areas-and-payment-for-ecosystem-services-pes/.

- Lundhede, T.; Wunder, S.; Katila, P.; Jellesmark Thorsen, B. Deliverable D4.1 - Assessing the Upscaling Potential of SINCERE IAs Using a Theory of Change Structure; H2020 project no.773702 RUR-05-2017; University of Copenaghen: Copenaghen, Denmark, 2022; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Katila, P.; Wunder, S.; Lovrić, M.; Pipart, N.; Lundhede, T.; Prokofieva, I.; Roux, J.-L.; Muys, B.; Jellesmark Thorsen, B.; Parra, C.; et al. Deliverable D4.2 - Synthesis Report of the Experiences and Lessons Learnt, Situating Them in the Global Experiences and Knowledge; H2020 project no.773702 RUR-05-2017; Natural resources Institute Finland: Helsinki, Finland, 2022; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- Laksono, R.A.; Sungkono, K.R.; Sarno, R.; Wahyuni, C.S. Sentiment Analysis of Restaurant Customer Reviews on TripAdvisor Using Naïve Bayes. 2019 12th International Conference on Information & Communication Technology and System (ICTS) 2019, 49–54, doi:10.1109/ICTS.2019.8850982. [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84787-548-8. [Google Scholar]

- Börner, J.; Baylis, K.; Corbera, E.; Ezzine-de-Blas, D.; Honey-Rosés, J.; Persson, U.M.; Wunder, S. The Effectiveness of Payments for Environmental Services. World Development 2017, 96, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Secchi, S.; Fargione, J.; Polasky, S.; Kraft, S. How to Sell Ecosystem Services: A Guide for Designing New Markets. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2013, 11, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomers, S.; Sattler, C.; Matzdorf, B. An Analytical Framework for Assessing the Potential of Intermediaries to Improve the Performance of Payments for Ecosystem Services. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, D. Investing in the Environmental Services of Australian Forest. In Forest Environmental Services: Market-Based Mechanisms for Conservation and Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; p. 320. ISBN 978-1-85383-888-0. [Google Scholar]

- Vuletić, D.; Krajter Ostoić, S.; Keča, L.; Avdibegović, M.; Potočki, K.; Posavec, S.; Marković, A.; Pezdevšek Malovrh, Š. Water-Related Payment Schemes for Forest Ecosystem Services in Selected Southeast European (SEE) Countries. Forests 2020, 11, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Yang, H.; Guo, X.; Zhao, S.; Jiang, Q. Payments for Ecosystem Services as an Essential Approach to Improving Ecosystem Services: A Review. Ecological Economics 2022, 201, 107591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Agrawal, A. Understanding the Social and Ecological Outcomes of PES Projects: A Review and an Analysis. Conservation and Society 2013, 11, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudyal, B.; Upadhaya, S.; Acharya, S.; Khanal Chhetri, B.B. Assessing Socio-Economic Factors Affecting the Implementation of Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) Mechanism. World 2021, 2, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspitasari, T.; Asdak, C.; Cahyandito, M.F. Factors Affecting Payments for Environmental Services (PES) Implementation in the Garang Watershed Management. E3S Web of Conferences 2021, 249, 01006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Document category | Document name |

|---|---|

| Institutional and legal framework | Constitution of the Republic of Croatia [72] Forest Act and its regulations (OG 68/18) [73] Environment Protection Act (OG 80/13, 153/13, 78/15, 12/18, 118/18) [74] |

| Stakeholders | Three Multi-Actor Group (MAG) meeting [75] |

| Characteristics of PES and project results | Report D4.1 - Assessing the upscaling potential of SINCERE IAs using a Theory of Change structure [76] Report D4.2 – Synthesis report of the experiences and lessons learnt, situating them in the global experiences and knowledge [77] |

| Category | Attribute | Role | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| User | Manager | Advisor | ||

| Emotions | Positive | |||

| Negative | ||||

| Neutral | ||||

| Elements for PES success | "Paying a tax for transit" | |||

| "Mindset" | ||||

| "Showing the difference between BAU and PES scenario" | ||||

| "Charge for the facilities/things that are used in the PES area" | ||||

| "Raising the awareness and education of users" | ||||

| "Good cooperation with all stakeholders" | ||||

| "Understanding the willingness to pay for forest ecosystem services" | ||||

| "Transparency" | ||||

| "Legislation" | ||||

| "Better communication to the public" | ||||

| Difficulties for PES implementation | "Different point of views" | |||

| "Misunderstanding" | ||||

| "Ownership conflicts" | ||||

| "Nature is free" | ||||

| "Do not consider different scenarios" | ||||

| Project added value | "Cooperation with different stakeholders" | |||

| "Implications only in theory and not in practice" | ||||

| "Good foundation for the future" | ||||

| "Raising the awareness about the benefits of forest ecosystem services to society" | ||||

| "Implementation and replication of a PES mechanism" | ||||

| "Nothing is changed" | ||||

| "Fostering new innovative approaches to the monetary valuation of ecosystem service" | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).