Submitted:

13 March 2023

Posted:

14 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

2.2. Sample

- -

- Aged at least 18;

- -

- At least one chronic condition (according to the International Classification of Primary Care-2 [47]), that has been present for at least six months;

- -

- At least one vulnerability criteria among the following: older people (over 65) living alone or in retirement homes, or in a situation of social or family isolation; persons receiving a disability pension or allowance; ethnic minorities; legal immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers (whose residence has been known for at least 6 months), and low-income (defined as below the poverty line at 60% of the median standard of living for the year 2015 [48]).

2.3. Outcomes

- Pain intensity in the EQ-5D-5L instrument (0: I have no pain or discomfort; 1: I have slight pain or discomfort; 2: I have moderate pain or discomfort; 3: I have severe pain or discomfort; 4: I have extreme pain or discomfort);

- Interference of pain with work and daily activities in the SF-12 instrument (During the past 4 weeks, how much did pain interfere with your normal work or other regular daily activities? 0: Not at all, 1: A little bit, 2: Moderately, 3: Quite a bit, 4: Extremely);

- Self-management of pain in the Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy (CDSE-6) instrument (How sure are you that you can keep any physical discomfort or pain of your condition from interfering with the things you want to do? Visual analogic 0-10 scale).

2.4. Data analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study population

3.2. Correlation between the different pain scales

3.3. Association between pain intensity and vulnerability factors

3.4. Multivariable analysis with pain intensity as the outcome (multinomial ordinal regression)

3.5. Multivariable analysis with a binary pain variable as the outcome (logistic regression)

3.6. Multivariable analyses with pain as an explanatory variable

3.7. Figures and tables

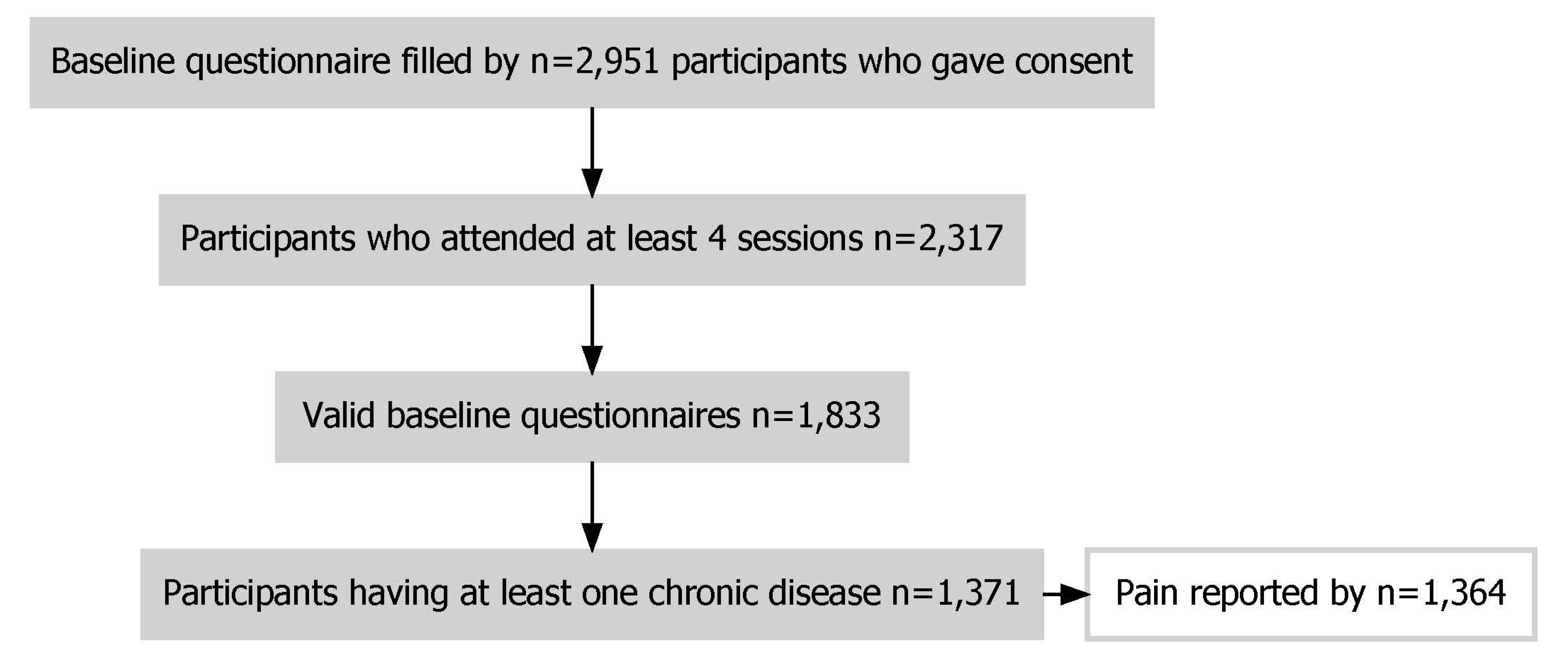

- Figure 1. Flow chart of sample selection.

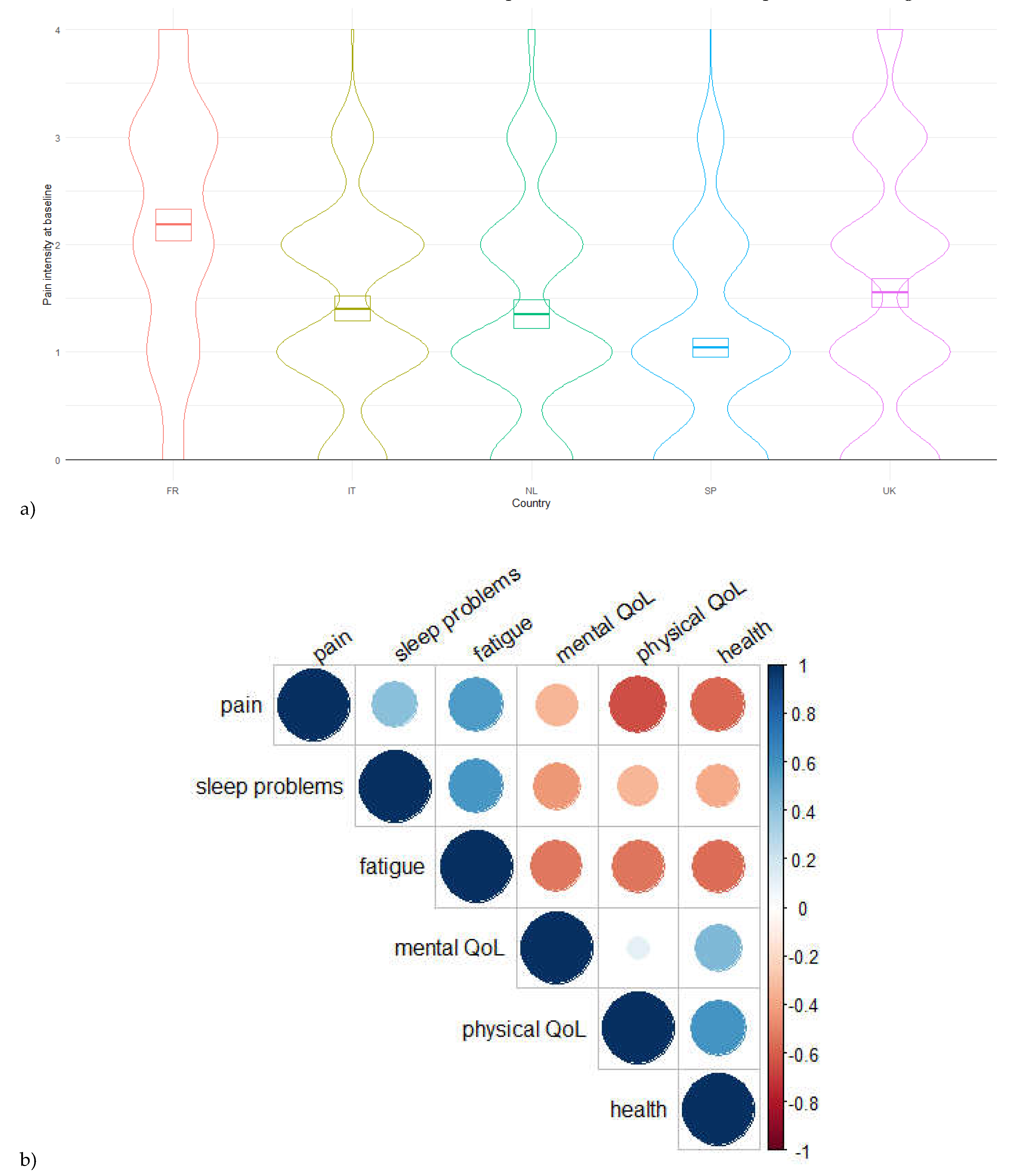

- Figure 2. a) Pain intensity across countries (kernel density estimate). b) Correlations’ matrice (Pearson’s coefficients) between pain intensity and quantitative variables reflecting quality of life. The areas and colors of circles represent the absolute value of correlation coefficients.

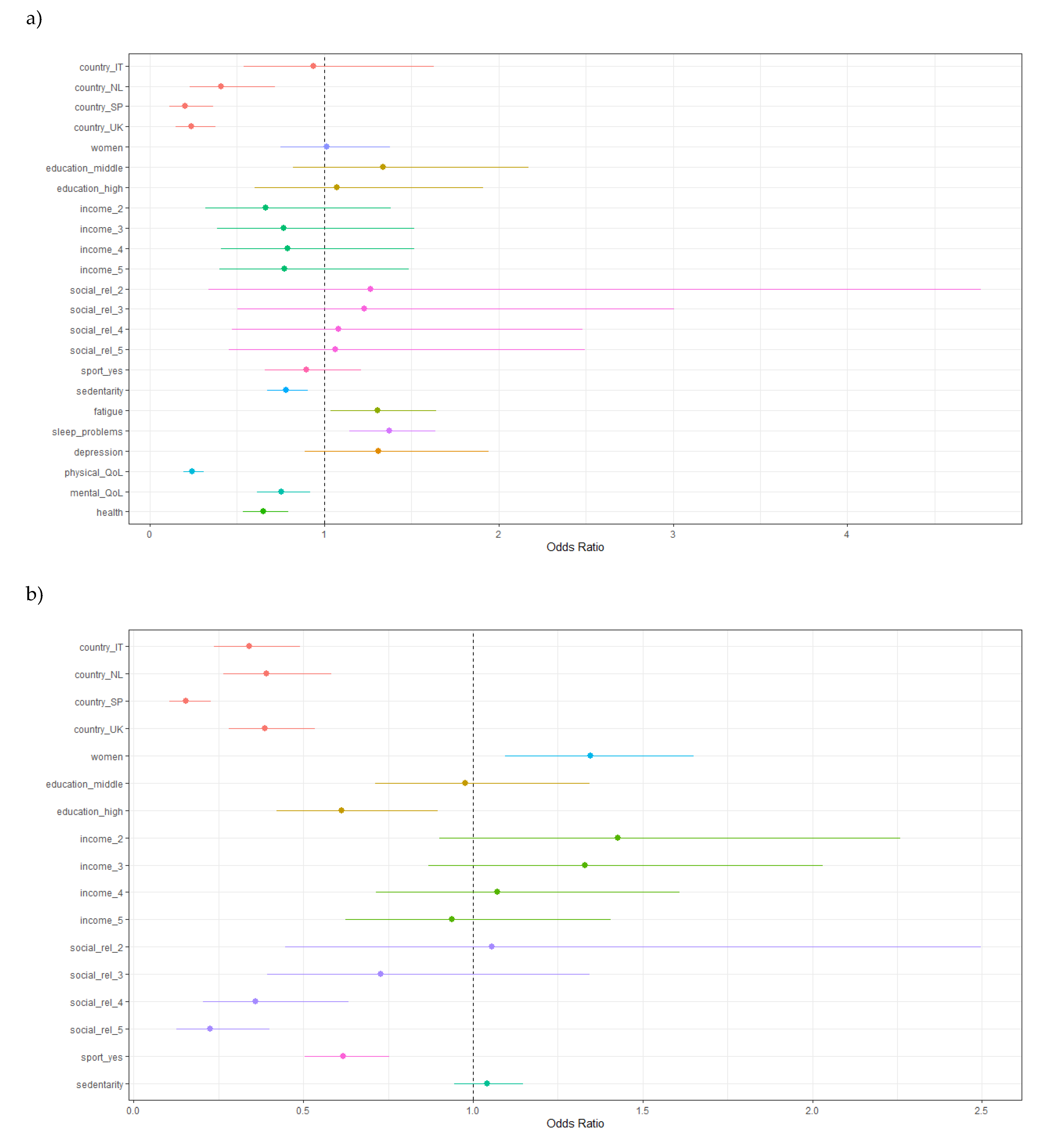

- Figure 3. Multivariable multinomial ordinal regression model, with pain intensity as the outcome. More pain on the right of the dashed line, less pain on the left of the dashed line. a) Model including all the variables that were significant in univariable models; b) Model including a restricted number of variables.

- Table 1. The instruments used in this study

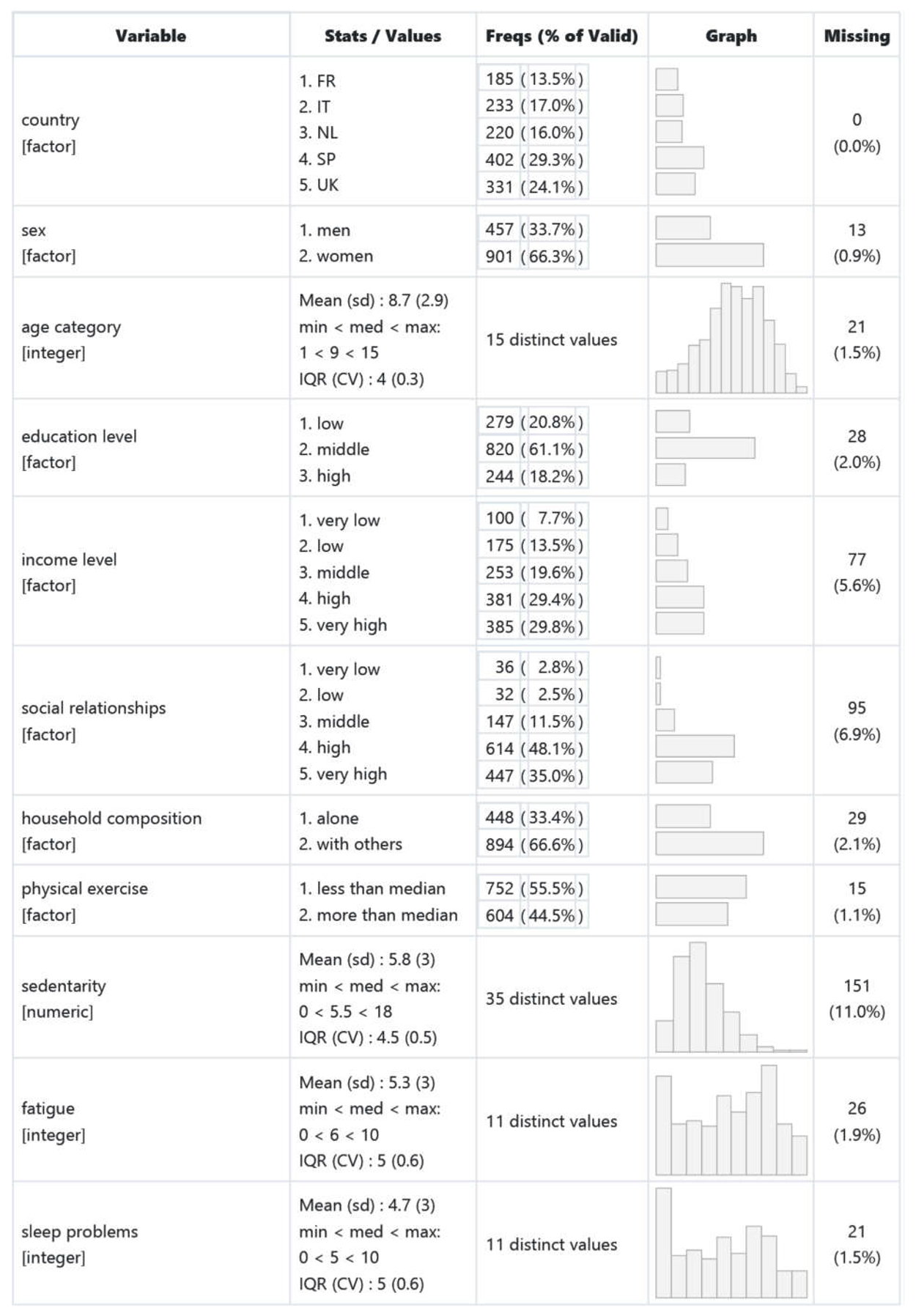

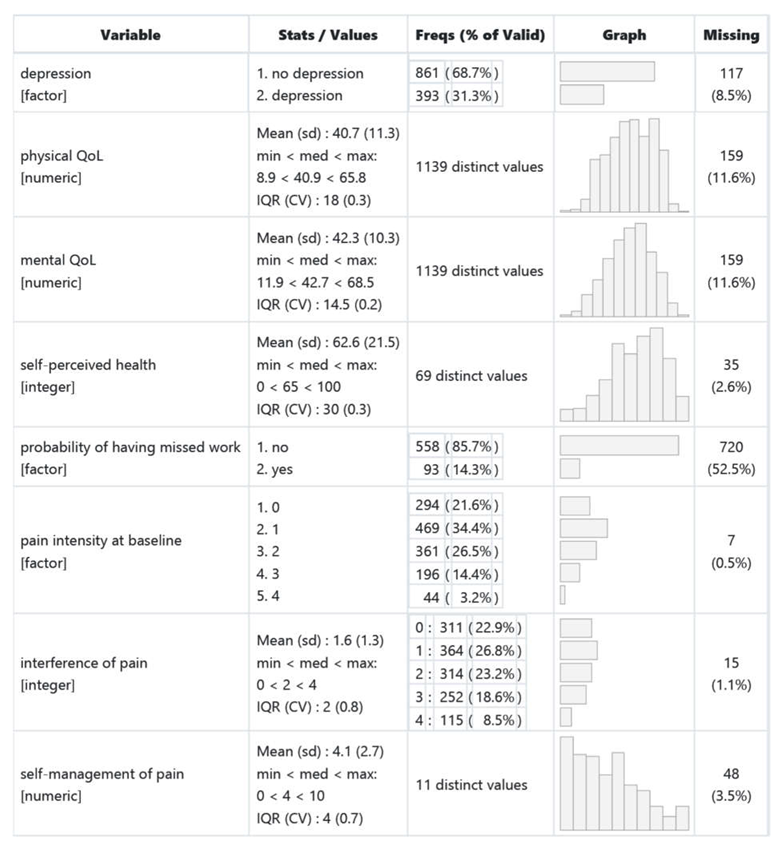

- Table 2. The variables used in this study

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Hecke, O.; Torrance, N.; Smith, B.H. Chronic pain epidemiology and its clinical relevance. Br. J. Anaesth. 2013, 111, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassieu, L.; Pagé, M.G.; Lacasse, A.; Laflamme, M.; Perron, V.; Janelle-Montcalm, A.; Hudspith, M.; Moor, G.; Sutton, K.; Thompson, J.M.; et al. Chronic pain experience and health inequities during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: qualitative findings from the chronic pain & COVID-19 pan-Canadian study. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, P.G. Long-Term Consequences of Chronic Pain: Mounting Evidence for Pain as a Neurological Disease and Parallels with Other Chronic Disease States. Pain Med. 2011, 12, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gureje, O.; Simon, G.E.; Von Korff, M. A cross-national study of the course of persistent pain in primary care. Pain 2001, 92, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.A.; Silman, A.J.; Macfarlane, G.J.; Nicholl, B.I.; Dickens, C.; Morriss, R.; Ray, D.; McBeth, J. The association between neighbourhood socio-economic status and the onset of chronic widespread pain: Results from the EPIFUND study. Eur. J. Pain 2009, 13, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korff, M.V.; Simon, G. The Relationship Between Pain and Depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 1996, 168, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorner, T.E.; Muckenhuber, J.; Stronegger, W.J.; Ràsky, É.; Gustorff, B.; Freidl, W. The impact of socio-economic status on pain and the perception of disability due to pain. Eur. J. Pain 2011, 15, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntyselkä, P.; Kumpusalo, E.; Ahonen, R.; Kumpusalo, A.; Kauhanen, J.; Viinamäki, H.; Halonen, P.; Takala, J. Pain as a reason to visit the doctor: a study in Finnish primary health care. Pain 2001, 89, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Pain Management; Eccleston, C. , Wells, C., Morlion, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, New York, 2017; ISBN 978-0-19-878575-0. [Google Scholar]

- Frymoyer, J.W.; Cats-Baril, W.L. An Overview of the Incidences and Costs of Low Back Pain. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1991, 22, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressler, H.B.; Keyes, W.J.; Rochon, P.A.; Badley, E. The Prevalence of Low Back Pain in the Elderly: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Spine 1999, 24, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SERRIE, A.; QUENEAU, P. Livre blanc de la douleur; COEGD (Comité d’Organisation des Etats Généraux de la Douleur): Paris, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baromètre santé 2010 Available online:. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/etudes-et-enquetes/barometres-de-sante-publique-france/barometre-sante-2010 (accessed on Oct 19, 2022).

- Mick, G.; Perrot, S.; Poulain, P.; Serrie, A.; Eschalier, A.; Langley, P.; Pomerantz, D.; Ganry, H. Impact sociétal de la douleur en France : résultats de l’enquête épidémiologique National Health and Wellness Survey auprès de plus de 15 000 personnes adultes. Douleurs Eval. - Diagn. - Trait. 2013, 14, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadley, R.M.; Armstrong, N.; Lee, Y.C.; Allen, A.; Kleijnen, J. Chronic Diseases in the European Union: The Prevalence and Health Cost Implications of Chronic Pain. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2012, 26, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breivik, H.; Collett, B.; Ventafridda, V.; Cohen, R.; Gallacher, D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur. J. Pain Lond. Engl. 2006, 10, 287–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, D.C.; Okifuji, A. Psychological factors in chronic pain: Evolution and revolution. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambamoorthi, U.; Tan, X.; Deb, A. Multiple Chronic Conditions and Healthcare Costs among Adults. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2015, 15, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanaway, J.D.; Afshin, A.; Gakidou, E.; Lim, S.S.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 2018, 392, 1923–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, P.; Müller-Schwefe, G.; Nicolaou, A.; Liedgens, H.; Pergolizzi, J.; Varrassi, G. The societal impact of pain in the European Union: health-related quality of life and healthcare resource utilization. J. Med. Econ. 2010, 13, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Determinants of Health; Marmot, M. , Wilkinson, R., Eds.; 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2005; ISBN 978-0-19-856589-5. [Google Scholar]

- Chapel, J.M.; Ritchey, M.D.; Zhang, D.; Wang, G. Prevalence and Medical Costs of Chronic Diseases Among Adult Medicaid Beneficiaries. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, S143–S154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegunde, D.O.; Mathers, C.D.; Adam, T.; Ortegon, M.; Strong, K. The burden and costs of chronic diseases in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 2007, 370, 1929–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; Phillips, D. Reaching and Engaging Hard-to-Reach Populations With a High Proportion of Nonassociative Members. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1292–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuscher, D.; Bukman, A.J.; van Baak, M.A.; Feskens, E.J.M.; Renes, R.J.; Meershoek, A. A lifestyle intervention study targeting individuals with low socioeconomic status of different ethnic origins: important aspects for successful implementation. BMC Public Health 2017, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Munter, J.S.L.; Agyemang, C.; van Valkengoed, I.G.M.; Bhopal, R.; Zaninotto, P.; Nazroo, J.; Kunst, A.E.; Stronks, K. Cross national study of leisure-time physical activity in Dutch and English populations with ethnic group comparisons. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.J.; Jones, D.A.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Reis, J.P.; Levy, S.S.; Macera, C.A. Race/Ethnicity, Social Class, and Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejiogu, N.; Norbeck, J.H.; Mason, M.A.; Cromwell, B.C.; Zonderman, A.B.; Evans, M.K. Recruitment and retention strategies for minority or poor clinical research participants: lessons from the Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of Diversity across the Life Span study. The Gerontologist 2011, 51 Suppl 1, S33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, N.I.; Drejer, S.; Burns, K.; Lundstrøm, S.L.; Hempler, N.F. A Qualitative Exploration of Facilitators and Barriers for Diabetes Self-Management Behaviors Among Persons with Type 2 Diabetes from a Socially Disadvantaged Area. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2020, 14, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.O.; Frankel, R.M.; Morgan, D.L.; Ricketts, G.; Bair, M.J.; Nyland, K.A.; Callahan, C.M. The meaning and significance of self-management among socioeconomically vulnerable older adults. J. Gerontol. B. Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2008, 63, S312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013-2020; Geneva, 2013.

- Haslbeck, J.; Zanoni, S.; Hartung, U.; Klein, M.; Gabriel, E.; Eicher, M.; Schulz, P.J. Introducing the chronic disease self-management program in Switzerland and other German-speaking countries: findings of a cross-border adaptation using a multiple-methods approach. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin, L.; Moquet, M.-J.; Jones, C.M. Réduire les inégalités sociales en santé; Inpes, 2010.

- Robles-Silva, L. The Caregiving Trajectory Among Poor and Chronically Ill People. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.R.; Sobel, D.S.; Stewart, A.L.; Brown, B.W.; Bandura, A.; Ritter, P.; Gonzalez, V.M.; Laurent, D.D.; Holman, H.R. Evidence Suggesting That a Chronic Disease Self-Management Program Can Improve Health Status While Reducing Hospitalization: A Randomized Trial. Med. Care 1999, 37, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.S.; Pisano, M.M.; Boone, A.L.; Baker, G.; Pers, Y.-M.; Pilotto, A.; Valsecchi, V.; Zora, S.; Zhang, X.; Fierloos, I.; et al. Evaluation Design of EFFICHRONIC: The Chronic Disease Self-Management Programme (CDSMP) Intervention for Citizens with a Low Socioeconomic Position. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, A.L.D.; Pisano-Gonzalez, M.M.; Valsecchi, V.; Tan, S.S.; Pers, Y.-M.; Vazquez-Alvarez, R.; Peñacoba-Maestre, D.; Baker, G.; Pilotto, A.; Zora, S.; et al. EFFICHRONIC study protocol: a non-controlled, multicentre European prospective study to measure the efficiency of a chronic disease self-management programme in socioeconomically vulnerable populations. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.R.; Sobel, D.S.; Ritter, P.L.; Laurent, D.; Hobbs, M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff. Clin. Pract. ECP 2001, 4, 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; Janssen, M.; Kind, P.; Parkin, D.; Bonsel, G.; Badia, X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996, 37, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, M. Assessment of Physical Activity: An International Perspective. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2000, 71, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Strine, T.W.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Berry, J.T.; Mokdad, A.H. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 114, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of Scales and Preliminary Tests of Reliability and Validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, T.A.; Montalvo, J.I.G. La Escala Socio-Familiar de Gijón: instrumento útil en el hospital general. Rev. Esp. Geriatría Gerontol. Organo Of. Soc. Esp. Geriatría Gerontol. 1998, 33, 179. [Google Scholar]

- García González, J.V.; Díaz Palacios, E.; Salamea García, A.; Cabrera González, D.; Menéndez Caicoya, A.; Fernández Sánchez, A.; Acebal García, V. [An evaluation of the feasibility and validity of a scale of social assessment of the elderly]. Aten. Primaria 1999, 23, 434–440. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmans, C.; Krol, M.; Severens, H.; Koopmanschap, M.; Brouwer, W.; Hakkaart-van Roijen, L. The iMTA Productivity Cost Questionnaire: A Standardized Instrument for Measuring and Valuing Health-Related Productivity Losses. Value Health J. Int. Soc. Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res. 2015, 18, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Halloran, J.; Miller, G.C.; Britt, H. Defining chronic conditions for primary care with ICPC-2. Fam. Pract. 2004, 21, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilan démographique 2017 - Insee Première - 1683 Available online:. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/3305173 (accessed on Apr 30, 2022).

- Rosete, A.A.; Pisano-González, M.M.; Boone, A.L.; Vazquez-Alvarez, R.; Peñacoba-Maestre, D.; Valsecchi, V.; Pers, Y.-M.; Zora, S.; Pilotto, A.; Tan, S.-S.; et al. Crossing intersectoral boundaries to reach out to vulnerable populations with chronic conditions in five European regions. Arch. Community Med. Public Health 2021, 7, 182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Esnaola, S. Desigualdades socioeconómicas en la mortalidad en el País Vasco y sus capitales: un análisis de áreas geográficas pequeñas (Proyecto MEDEA).

- CHALLIER, B.; VIEL, J.F.; FRA, D. de S.P.F. de M. et de P. de B.B. Pertinence et validité d’un nouvel indice composite français mesurant la pauvreté au niveau géographique. Rev. Dépidémiologie Santé Publique RESP 2001, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, N.C. , Annibale Biggeri, Laura Grisotto, Barbara Pacelli, Teresa Spadea, Giuseppe L’indice di deprivazione italiano a livello di sezione di censimento: definizione, descrizione e associazione con la mortalità Available online:. Available online: www.epiprev.it. (accessed on Apr 19, 2022).

- Peters, S. 2015 English Indices of Deprivation: map explorer Available online:. Available online: http://dclgapps.communities.gov.uk/imd/http;//dclgapps.communities.gov.uk/imd/idmap.html (accessed on Apr 19, 2022).

- Crawley, M.J. The R Book; Wiley–Blackwell: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-470-97392-9. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; White, I.R.; Carlin, J.B.; Spratt, M.; Royston, P.; Kenward, M.G.; Wood, A.M.; Carpenter, J.R. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009, 338, b2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M. , & Mayer, M. M. Package ‘missRanger’. In; 2019.

- Roth, R.S.; Punch, M.R.; Bachman, J.E. Educational achievement and pain disability among women with chronic pelvic pain. J. Psychosom. Res. 2001, 51, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portenoy, R.K.; Ugarte, C.; Fuller, I.; Haas, G. Population-based survey of pain in the united states: Differences among white, african american, and hispanic subjects. J. Pain 2004, 5, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittendorfer-Rutz, E.; Dorner, T.E. Socio-economic factors associated with the 1-year prevalence of severe pain and pain-related sickness absence in the Austrian population. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2018, 130, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurer, S.; Shields, M.A.; Jones, A.M. Socio-economic inequalities in bodily pain over the life cycle: longitudinal evidence from Australia, Britain and Germany. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2014, 177, 783–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.Ll.; Conway, P.; Currie, C.J. The relationship between self-reported severe pain and measures of socio-economic disadvantage. Eur. J. Pain 2011, 15, 1107–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, V.R.; Macfarlane, T.V.; Macfarlane, G.J. Why is pain more common amongst people living in areas of low socio-economic status? A population-based cross-sectional study. Br. Dent. J. 2003, 194, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonska, B.; Soares, J.J.F.; Sundin, Ö. Pain among women: Associations with socio-economic and work conditions. Eur. J. Pain 2006, 10, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saastamoinen, P.; Leino-Arjas, P.; Laaksonen, M.; Lahelma, E. Socio-economic differences in the prevalence of acute, chronic and disabling chronic pain among ageing employees. Pain 2005, 114, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomtén, J.; Soares, J.J.F.; Sundin, Ö. Pain among women: Associations with socio-economic factors over time and the mediating role of depressive symptoms. Scand. J. Pain 2012, 3, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, J.R.H.; Sani, F.; Madhok, V.; Norbury, M.; Dugard, P. The pain of low status: the relationship between subjective socio-economic status and analgesic prescriptions in a Scottish community sample. Psychol. Health Med. 2016, 21, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalstra, J. a. A.; Kunst, A.E.; Borrell, C.; Breeze, E.; Cambois, E.; Costa, G.; Geurts, J.J.M.; Lahelma, E.; Van Oyen, H.; Rasmussen, N.K.; et al. Socioeconomic differences in the prevalence of common chronic diseases: an overview of eight European countries. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodner, D.L.; Spreeuwenberg, C. Integrated care: meaning, logic, applications, and implications – a discussion paper. Int. J. Integr. Care 2002, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, R. Canada: Application of a Coordinated-Type Integration Model for Vulnerable Older People in Québec: The PRISMA Project. In Springer Books; Springer, 2021; pp. 1075–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Bonevski, B.; Randell, M.; Paul, C.; Chapman, K.; Twyman, L.; Bryant, J.; Brozek, I.; Hughes, C. Reaching the hard-to-reach: a systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrell, L.N.; Kneipp, S.M. Strategies for recruiting populations to participate in the chronic disease self-management program (CDSMP): A systematic review. Health Mark. Q. 2017, 34, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, S.M.; Hancock, B. “Reaching the hard to reach” - lessons learned from the VCS (voluntary and community Sector). A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, E.; De Jong, N.P.; Blanc, S.; Simon, C.; Bessesen, D.H.; Bergouignan, A. Physiology of physical inactivity, sedentary behaviours and non-exercise activity: insights from the space bedrest model. J. Physiol. 2022, 600, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butchart, A.; Kerr, E.A.; Heisler, M.; Piette, J.D.; Krein, S.L. EXPERIENCE AND MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC PAIN AMONG PATIENTS WITH OTHER COMPLEX CHRONIC CONDITIONS. Clin. J. Pain 2009, 25, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruehl, S.; Chung, O.Y.; Jirjis, J.N.; Biridepalli, S. Prevalence of Clinical Hypertension in Patients With Chronic Pain Compared to Nonpain General Medical Patients. Clin. J. Pain 2005, 21, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, S.; Chugh, G.; Asghar, M. Chapter One - Inflammation in Anxiety. In Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology; Donev, R., Ed.; Inflammation in Neuropsychiatric Disorders; Academic Press, 2012; Volume 88, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

| Name of instrument and reference | Description | Simplified variable | Number of items |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy (CDSE) [38] | ability to deal with fatigue, pain, emotional distress, health problems | 6 | |

| EQ-5D-5L [39] | mobility, self-care, activity, pain, anxiety | 5 | |

| Euro-Qol visual analogue scale (EQ VAS) [40]: experienced current health | 100-level visual analogue scale, where the endpoints are labelled ‘The best health you can imagine’ and ‘The worst health you can imagine’ | 1 | |

| Physical exercise (developed specifically for the CDSMP) | time spent weekly on various activities such as walking, swimming, cycling, and aerobics | dichotomous variable (0: score below the median, 1: score above) | 6 |

| International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) [41] | sedentary behavior: week and week-ends’ numbers of hours sitting daily | standardised variable combining weeks and week-ends | 2 |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) [42] | depression scale | dichotomous variable (0: PHQ-8 < 10, 1: PHQ-8 >=10) | 8 |

| Sleeping problems and fatigue (developed specifically for the CDSMP) | 10-level visual analog scales | 2 | |

| SF-12 [43] | health-related quality of life | 0-100 continuous scores: Mental Component Summary, Physical Component Summary | 12 |

| Gijon’s socio-familial evaluation scale [44,45]: income | 1) no income or less than minimum pension allowance, 2) minimum pension (social welfare or disability pension), 3) from the minimum pension to the minimum wage, 4) from the minimum wage to 1.5 times the minimum wage, 5) more than 1.5 times the minimum wage (income scales were adjusted to the local situation in each country) | 1 | |

| Gijon’s socio-familial evaluation scale [44,45]: social relationships | 1) doesn’t leave the house and doesn’t receive visits, 2) doesn’t leave the house but receives visits, 3) only relates to family or neighbours/friends, 4) relates to family and neighbours/friends, 5) has social relationships | 1 | |

| Productivity Costs Questionnaire (PCQ) [46]: work absenteeism | Have you missed work in the last 4 weeks as a result of being sick: yes I have missed X days / no | 1 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).