1. Introduction

Monkeypox is a zoonotic disease endemic to Central and West Africa[

1], caused by the Monkeypox virus, a deadly virus militating against human health. The MPXV is a member of the Poxviridaefamily with other members such as variola virus (the virus responsible for smallpox disease), vaccinia virus (employed in the smallpox vaccine) [

2], and ectromelia, camelpox, and cowpox viruses respectively [

3].

Monkeypox was first discovered in 1958 when there was an occurrence of a “pox-like” disease in two outbreaks in monkey colonies that had been set aside for research purposes. Although this “pox-like” disease was given the name “monkeypox,” the original generating source has remained unclear. Rodents found in Africa and non-human primates (i.e. monkeys) have been proposed as the reservoirs of the virus and the most probable primary cause of infections in Humans [

4].

After the discovery of human monkeypox in 1970, several other human cases have been reported in many central and western African countries. Clinically, the symptoms of human monkeypox are almost indistinguishable from symptoms of smallpox but they appear milder and are rarely fatal. However, the enlargement of the lymph node occurring early at the onset of fever is a major distinguishing symptom between monkeypox and smallpox. There is usually a rash appearing usually within the first three days after the onset of fever and lymphadenopathy, with the appearance of lesions simultaneously, and evolving at an equal speed. Another important characteristic peculiar to monkeypox is that the pox distribution is mainly peripheral but in severe cases covers the whole body with an infection that can last up to 4 weeks until the lesion desquamates [

5].

To date, there have been cases of human monkeypox in 10 different African countries – the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sierra Leone, Republic of the Congo, Cameroon, Gabon Central African Republic, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Nigeria, and South Sudan [

6,

7]. This article reviews the epidemiology, endemicity, and possible solutions to reduce the spread of human monkeypox in Nigeria. Understanding the true state of human monkeypox in Nigeria would be impactful in the efforts to limit the spread, direct decision-making, and policy integration in public health as well as contribute to the current pool of information available on human monkeypox.

2. Methodology

Search Method

Literature search for the review was performed in“Science direct”, “Google scholar”, “PubMed” and also in “AJOL”, and “NATURE” journals using the combination of words as search terms such as; “Monkeypox in Nigeria” and “Human monkeypox in Nigeria”, “MPXV in Nigeria” to find articles published before October 30, 2022. Also, some published articles by the WHO and Nigeria Center for disease prevention and control were included in the analysis.

Eligibility Criteria (Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria)

Identification of studies meeting the inclusion criteria was done by the review authors, who screened the titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles. After the selected articles were read, a conclusive decision was made for each study.

The inclusion criteria include studies based on experimental data, studies discussing either clinical manifestation, Epidemiology of Human monkeypox, studies based on transmission and host reservoir of MPXV, and studies containing information on Occurrence, pathogenesis, and symptoms of Monkeypox. Studies with old data that were not pertinent to the aim of the study were excluded. Studies not including Nigeria were excluded. Studies in Africa but not including Nigeria were excluded.

3. Results

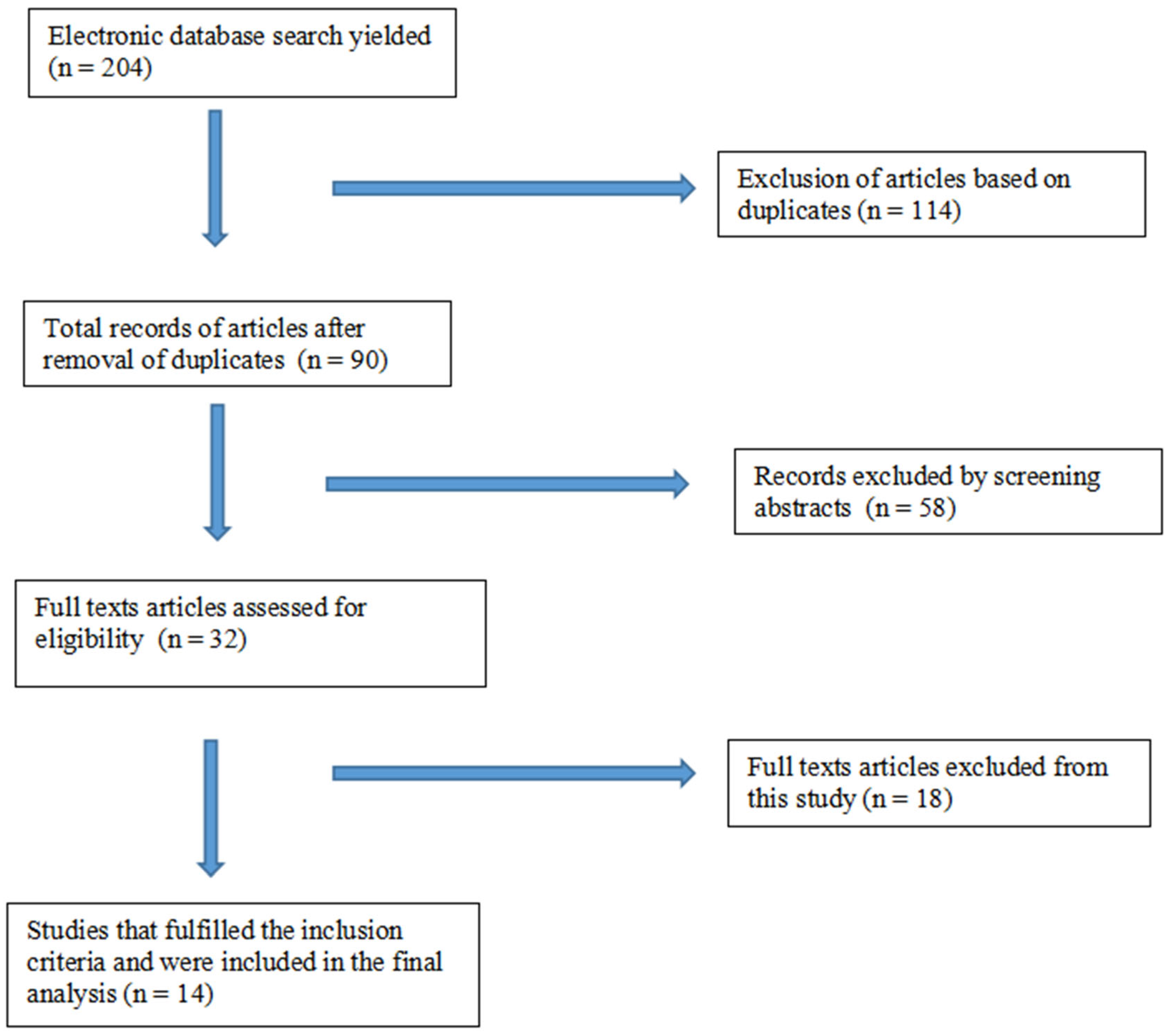

The database search identified a total of 204 articles, amongst which 11 articles were selected for this study. An additional 6 articles were added to the study through the reference list search. A total of 14 articles were analyzed for the review. The screening procedure for the included studies is shown in

Figure 1.

4. Occurrence of Human Monkeypox in Nigeria

Prior to the recent outbreak of monkeypox in Nigeria, the largest and most lethal outbreak was in 2017 which came after the monkeypox outbreak of 1978 [

8]. The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) on September 22, 2017, commenced an investigation on the monkeypox outbreak following the identification of a child with a suspected case of monkeypox [

9]. This action showed the preparedness of the NCDC at this time for the outbreak. It activated an emergency operations center (EOC) on October 9, 2017, to implement plans against the outbreak [

10]. The plan mainly focused on the research into the epidemiology of MPXV in the regions with a high risk of the Human-Environmental-Animal interface. Improved diagnosis and state-of-art sequencing were employed to assess various factors contributing to and enhancing the spread of monkeypox [

8,

11]. The data that was generated in 2017 suggested that the cases of human monkeypox and the 2017 outbreak were not linked epidemiologically. It was also noted that there was a possibility of the outbreak being connected to multiple sources with fewer human-to-human transmissions. This shows the existence of another ecological niché in humans where the expansion of the virus can occur aside from its natural reservoir. However, the specific source and role(s) played by the other abiotic factors in the Nigeria outbreak are not fully elucidated.

5. Declining Population Immunity in Nigeria

The significant epidemiological distribution of monkeypox across West Africa and Nigeria provides an avenue for continuous spread across other regions and internationally. Whilst the stoppage of vaccination against smallpox stands as a huge pointer to the occurrences of monkeypox in Nigeria because of a reduction in herd immunity, chances exist that it could have risen from the increased human contact with other humans that have remained as endemic carriers of the MPXV [

10,

11]. Cases of protection against the MPXV as a result of vaccination against smallpox have been shown in Studies on monkeys [

12]. There is actually a concern that the mass vaccination against smallpox might in one way or another curb the spread of the human monkeypox virus. This concern is not baseless as there is a possibility that the absence of protection capability against MPXV in the younger age brackets that have not been vaccinated and the decreasing herd- immunity among the older vaccinated age groups might be a risk factor in the increased susceptibility to the human monkeypox infection [

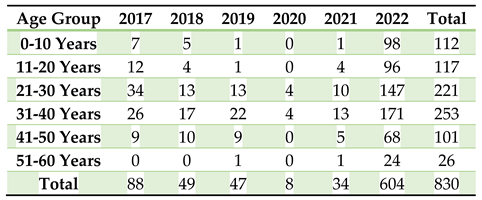

13]. This case is evident in Nigeria as the larger chunk of confirmed cases are found in the age group between 21-40 years having a median age of 31 years(

Table 1).

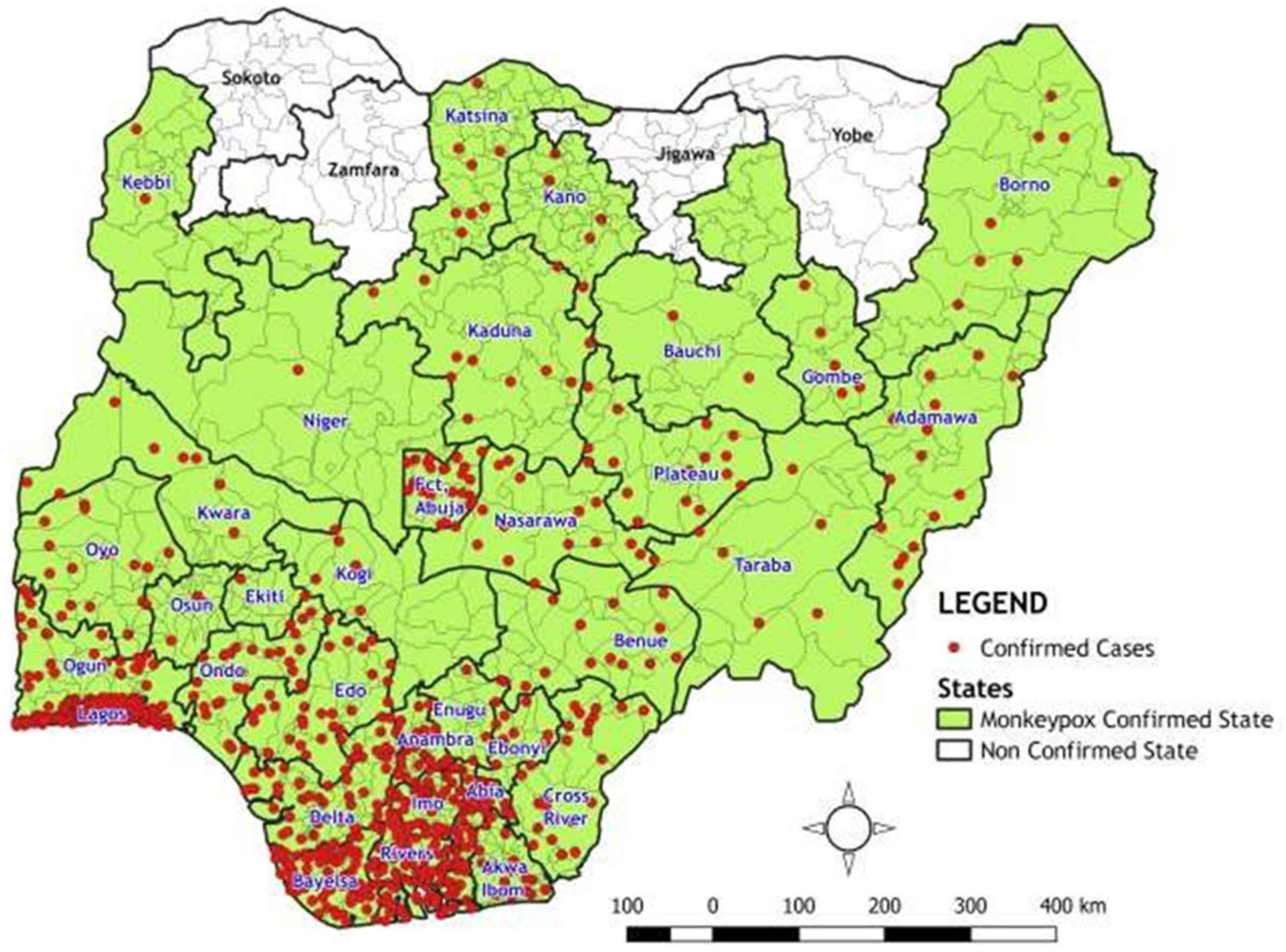

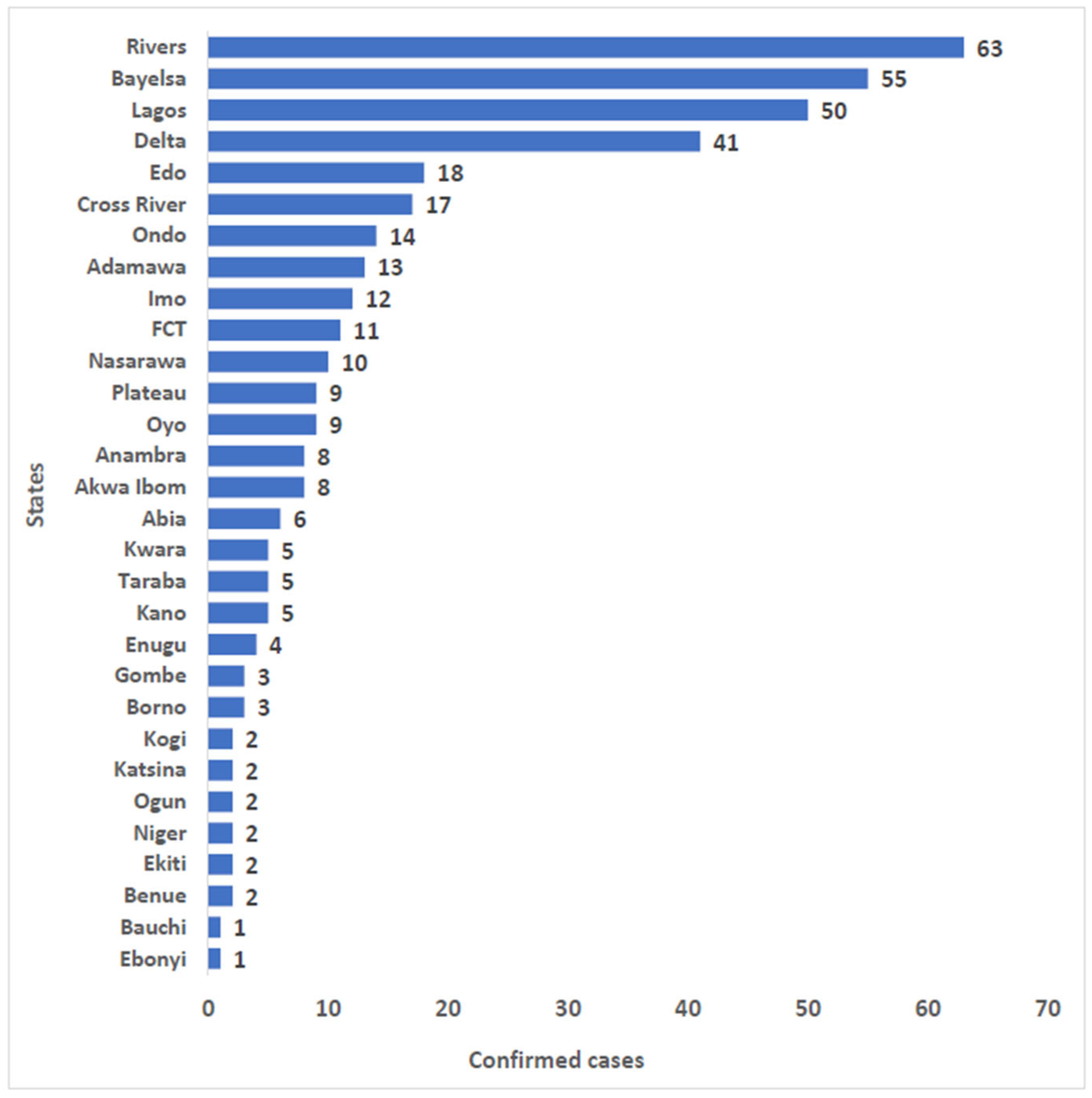

6. Geographic Distribution and Epidemiology of Human Monkeypox in Nigeria

The World Health Organization (WHO) [

6,

7] describes monkeypox as a zoonotic infection of viral origin occurring majorly in remote parts of central and west Africa, along the tropical rainforests”. This is the most probable case in Nigeria as a large chunk of confirmed cases come from the state where the country's dense forests and swamps are concentrated. The majority of Nigeria's rainforests are situated in the Niger Delta and are concentrated in the states of Rivers, Bayelsa, Edo, Cross River, Ondo, Ekiti, and Osun. Some of these states have over the years become the largest epicenter of confirmed cases in Nigeria (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) and serve as a natural ecological niche of monkeypox [

8]. Satellite imagery has shown that there is increasing development in the southern region of Nigeria which is made at the cost of these forests. [

14]. The increase in the development of these areas also increases the chances of animal reservoirs, such as rodents, rabbits, and primates, having lost their natural habitat to have increased contact with humans [

15].

It is also common to find monkeys allowed to roam freely in the compound and homes of the people without being molested as the people of the community consider the animal sacred and never kill or eat it. “Awka na aso enwe”, meaning Awka forbids or doesn’t eat monkeys, is a popular term used in the Capital City of Anambra state. This is also the tale in some parts of Enugu, Abia, and Ebonyi State. Also, In Nigeria and most parts of Africa, bushmeat is a delicacy. It refers to any wild animal that is killed for consumption, including, snakes, fruit bats, wild rats, antelopes, and porcupines. Hunters and dealers of ‘bush meat’ are key players in the process of any ‘spillover’ of the MPXV pathogen in Nigeria. Bayelsa, Delta, and River state are some states in Nigeria where the bush meat business is prominent and thriving.

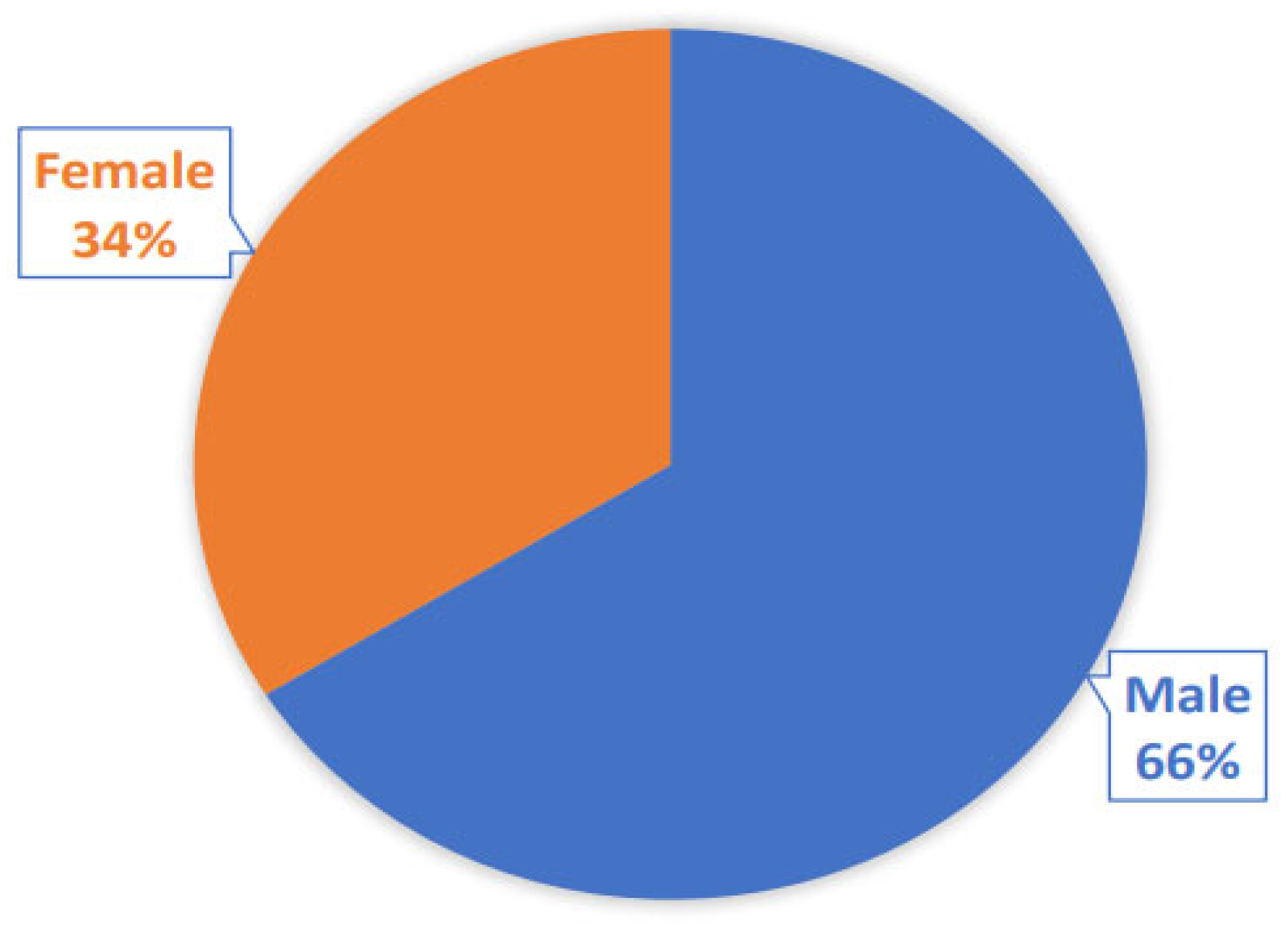

Previous studies have discovered a high serological prevalence of Orthopoxvirus (OPXV) specific IgG in inhabitants of these forest locations, indicating constant continuous contact with monkeypox virus and other Orthopoxviruses [

16,

17]. Also, the results published by the Nigeria CDC on the confirmed cases of monkeypox in Nigeria show that there is a higher prevalence of confirmed cases occurring among men in Nigeria (

Figure 4). This is most likely due to the fact that men are more involved in activities in relation to wild animals, such as hunting and trading bush meat, and as such are in contact with the MPXV and other OPXV.

Fresh cases of human monkeypox are continuously been recorded in Nigeria and as of October 30, 2022, 2061 suspected cases and 803 (40.3%) confirmed cases (550 male and 280 female) had been noted in 32 states and FCT since the re-emergence of monkeypox in 2017 [

18] across various age groups. With 803 confirmed cases having been recorded in 32 states and FCT (Rivers, Bayelsa, Ondo, Gombe, Taraba, Kano, Niger, Cross River, Imo, Ogun, Ebonyi, Kogi, Kwara, Borno, Katsina, Adamawa, Akwa Ibom, Lagos, Delta, Bauchi, Abia, Oyo, Enugu, Ekiti, Nasarawa, Benue, Plateau, Edo, Anambra, Kaduna, Osun, Kebbi) and fifteen deaths in eleven states (Lagos, Imo, Edo, FCT, Rivers, Cross River, Delta, Akwa Ibom, Taraba, Kogi, Ondo) there is an indication of endemicity of the MPXV in Nigeria

7. Rise in Monkeypox Cases in Nigeria: Underlying Causes and Proposed Solution

The resurgence of Monkeypox in Nigeria has become a significant challenge for health authorities, policymakers, and local communities in Nigeria. This zoonotic disease, similar to smallpox, is transmitted through the exchange of bodily fluids with infected animals like rodents, monkeys, and squirrels. However, it can also be transmitted through close contact with an infected individual. One of the primary drivers behind the recent rise in monkeypox cases in Nigeria is the growing contact between humans and wildlife, which have been displaced due to deforestation, conflict, and poverty, particularly in North-eastern Nigeria. This leads to increased population migration into forests, reliance on wild animals for food, and, therefore, a higher likelihood of human-animal contact and transmission of the virus. Moreover, excessive and unregulated contact with wild animals that serve as animal reservoirs of MPXV by residents of rainforest regions could be contributing factors to the reemergence of the disease. Additionally, inadequate surveillance and disease monitoring systems in the country could cause cases to go unnoticed or underreported, making it challenging to track and control the outbreak. Furthermore, increased urbanization and various activities such as traveling could also play a crucial role in human-to-human transmission of MPXV. To combat the reemergence of monkeypox in Nigeria, a comprehensive approach is necessary.

First, the One Health approach, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health, could be a promising way to decrease the incidence of monkeypox. This could involve coordinated efforts between human health, veterinary doctors, and environmental health professionals to address gaps in epidemiological data, identify specific animal reservoirs, and transmission patterns of the MPXV[

19]. It is also essential to improve surveillance systems to effectively detect, monitor, and respond to outbreaks. This could be achieved by increasing funding for disease surveillance and strengthening collaboration between different arms of government, NGOs, and community-based organizations[

19].

Moreover, regulations should be put in place to limit the importation of rodents and non-human primates. Infected animals should be isolated from other animals that have been captured and placed into immediate quarantine. Raising public awareness about the disease and its prevention is also critical. This could be accomplished through campaigns, community engagement, and outreach programs aimed at educating high-risk groups such as farmers, herdsmen, and other members of the public. Finally, the use of convalescent plasma from recovering patients has been shown to be effective in treating Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Ebola during previous epidemics that have caused global havoc[

20,

21]. This medical intervention dates back to the 1918 H1N1 influenza virus outbreak, where blood serum was administered to over 1700 patients. The use of convalescent plasma holds enormous promise for slowing the spread of infection and preventing the massive mortality that could result from a delay in the production of an effective medication or vaccine[

21,

22].

In conclusion, further research is necessary to fully understand all the factors contributing to the reemergence of monkeypox in Nigeria. This could facilitate the development of novel therapeutic compounds toward the protein target of the MPXV using computational methods and antiviral therapy to alleviate the disease's impact.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to give special thanks to the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, for making the data on Monkeypox in Nigeria Accessible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Khodakevich, L.; Jezek, Z.; Messinger, D. Monkeypox virus: ecology and public health significance. Bull. World Health Organ. 1988, 66, 747–752. [Google Scholar]

- Huygelen, C. Jenners koepokentstof in het licht van de moderne vaccinologie [Jenner's cowpox vaccine in light of current vaccinology]. Verh K Acad Geneeskd Belg. 1996;58(5):479-536; discussion 537-8. Dutch. [PubMed]

- Nalca A, Rimoin AW, Bavari S, Whitehouse CA. The re-emergence of monkeypox: prevalence, diagnostics, and countermeasures. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Dec 15;41(12):1765-71. Epub 2005 Nov 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC, 2017: Emergence of monkeypox in West Africa and Central Africa, 1970–2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: multistate outbreak of monkeypox—Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003a; 52:642.

- Ladnyi ID, Jezek Z, Fenner F, Henderson DA, Arita I. Smallpox and its Eradication Chapter: Human Monkeypox and Other Poxvirus Infections of Man. Geneva: World Health Organization (1988).

- WHO. Emergencies. Disease outbreaks. 2018a http://www.who.int/emergencies/ diseases/en/.

- WHO. Fact sheet on Monkeypox. 2022.

- Yinka-Ogunleye A, Aruna O, Dalhat M, Ogoina D, McCollum A, Disu Y, et al.; CDC Monkeypox Outbreak Team. Outbreak of human monkeypox in Nigeria in 2017–18: a clinical and epidemiological report. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:872–9. [CrossRef]

- Eteng, W.E., Mandra, A., Doty, J., Yinka-Ogunleye, A., Aruna, S., Reynolds, M.G. (2018): Notes from the field: responding to an outbreak of monkeypox using the one health approach — Nigeria, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep., ;67 (37):1040–1041. Mortal Wkly. Rep. [CrossRef]

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Situation report: update of monkeypox outbreak in Nigeria, 2018 Feb 25. https://ncdc.gov.ng/ themes/common/files/sitreps/7ba9ce49faf09f5212c1dbb48 b31184b.pdf.

- Faye O, Pratt CB, Faye M, Fall G, Chitty JA, Diagne MM, et al. Genomic characterisation of human monkeypox virus in Nigeria. LancetInfect Dis 2018;18(March (3)):246. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, S.; Hickman, R.L.; Woodin, W.L., Jr.; Huxsoll, D.L. Monkeypox: experimental infection in chimpanzee (Pan satyrus) and immunization with vaccinia virus. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1968, 29, 1675–1680. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sklenovská, N. , Van Ranst, M. Emergence of monkeypox as the most important orthopoxvirus infection in humans Front Public Health, 4 (September (6)) (2018), p. 241. eCollection 2018. [CrossRef]

- Izah LN, Majid Z, Mohd Ariff MF, Mohammed HI. Determining land use change pattern in southern Nigeria: a comparative study. IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci. 2018;169:012040. [CrossRef]

- Faust CL, McCallum HI, Bloomfield LSP, Gottdenker NL, Gillespie TR, Torney CJ, et al. Pathogen spillover during land conversion. Ecol Lett. 2018;21:471–483. [CrossRef]

- Leendertz SAJ, Stern D, Theophil D, Anoh E, Mossoun A, Schubert G, et al. A cross-sectional serosurvey of antiorthopoxvirus antibodies in central and western Africa. Viruses. 2017;9:278. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds MG, Carroll DS, Olson VA, Hughes C, Galley J, Likos A, et al. A silent enzootic of an orthopoxvirus in Ghana, West Africa: evidence for multi-species involvement n the absence of widespread human disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;82:746–754. [CrossRef]

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Situation report: update of a monkeypox outbreak `in Nigeria, 2022 July 31. https://ncdc.gov.ng/diseases/sitreps/?cat=8&name=An%20Update%20of%20Monkeypox%20Outbreak%20in%20Nigeria.

- Akinsuyi, O.S.; Orababa, O.Q.; Juwon, O.M.; Oladunjoye, I.O.; Akande, E.T.; Ekpueke, M.M.; Emmanuel, H. One Health approach, a solution to reducing the menace of multidrug-resistant bacteria and zoonoses from domesticated animals in Nigeria–A review. Global Biosecurity 2021, 3, 10–31646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, Benjamin Ayodipupo, Tosin Emmanuel Adetobi, Oluwamayowa Samuel Akinsuyi, Otunba Ahmed Adebisi, and Elizabeth Oreoluwa Folajimi. "Computational study of the therapeutic potential of novel heterocyclic derivatives against SARS-CoV-2." COVID 1, no. 4 (2021): 757-774. [CrossRef]

- Ekpunobi N, Markjonathan I, Olanrewaju O, Olanihun D. Idiosyncrasies of COVID-19; A Review. Iran J Med Microbiol. 2020; 14 (3):290-296. [CrossRef]

- Maxmen, A. "How blood from coronavirus survivors might save lives" Nature. 2020; 580:16-17. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).