Submitted:

19 March 2023

Posted:

21 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data Sources

3. Methods

3.1. Building Maps of Public and Private Land Tenure

- (i)

- Identify all properties in the dataset that have overlapping areas.

- (ii)

-

For each pair of overlapping properties, do as follows:

- Determine the number of overlaps for each property.

- If one property has more overlaps than the other, remove the overlapping area from that property.

- If both properties have the same number of overlaps, remove the overlapping area from the property with the larger area.

- (iii)

- Repeat the process for all overlapping properties until all intersecting areas have been removed.

3.2. Forest Protection Mandates

- Article 12 §5 provides a special condition for states with over 65% of their area occupied by conservation units and indigenous lands. Private properties in those states benefit from an unconstrained legal reserve reduction from 80% to 50%.

- Article 67 provides a waiver for small rural properties. For these lands, the legal reserve is taken as the remaining forest area as of 22 July 2008. The Law grants this amnesty if owners did not deforest their lands after that date.

- Article 12 §4 singles out municipalities where more than 50% of its area is taken by conservation units and indigenous lands.

- Article 13 allows states to define special areas of ecological-economic zoning where the legal reserve is to be reduced.

- Article 68 considers rural properties that had cut forests up to 25 July 1996 respecting the legal reserve limit of 50% valid before that date and that have not deforested their lands since.

3.3. Areas of Permanent Preservation

4. Results and Discussion

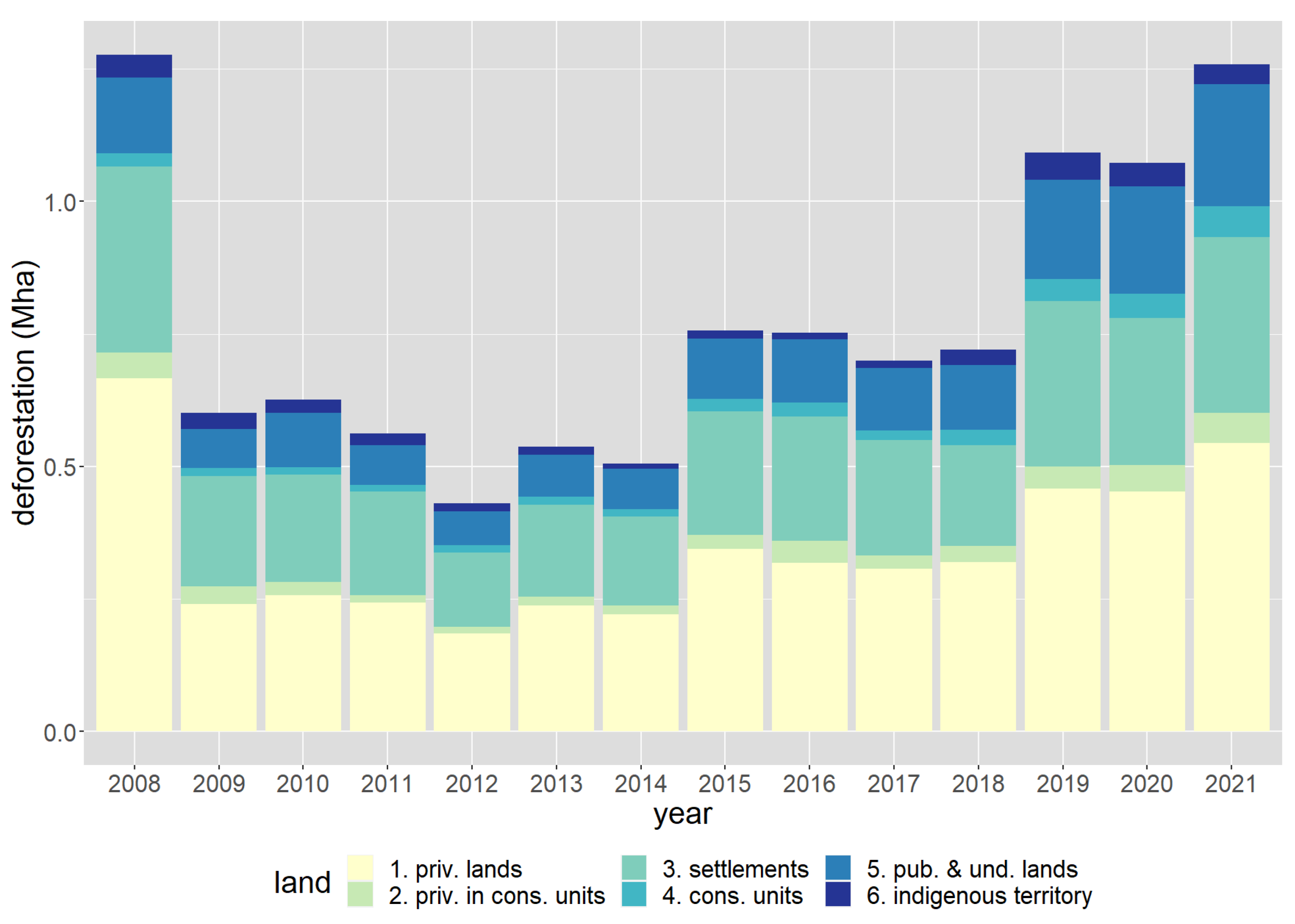

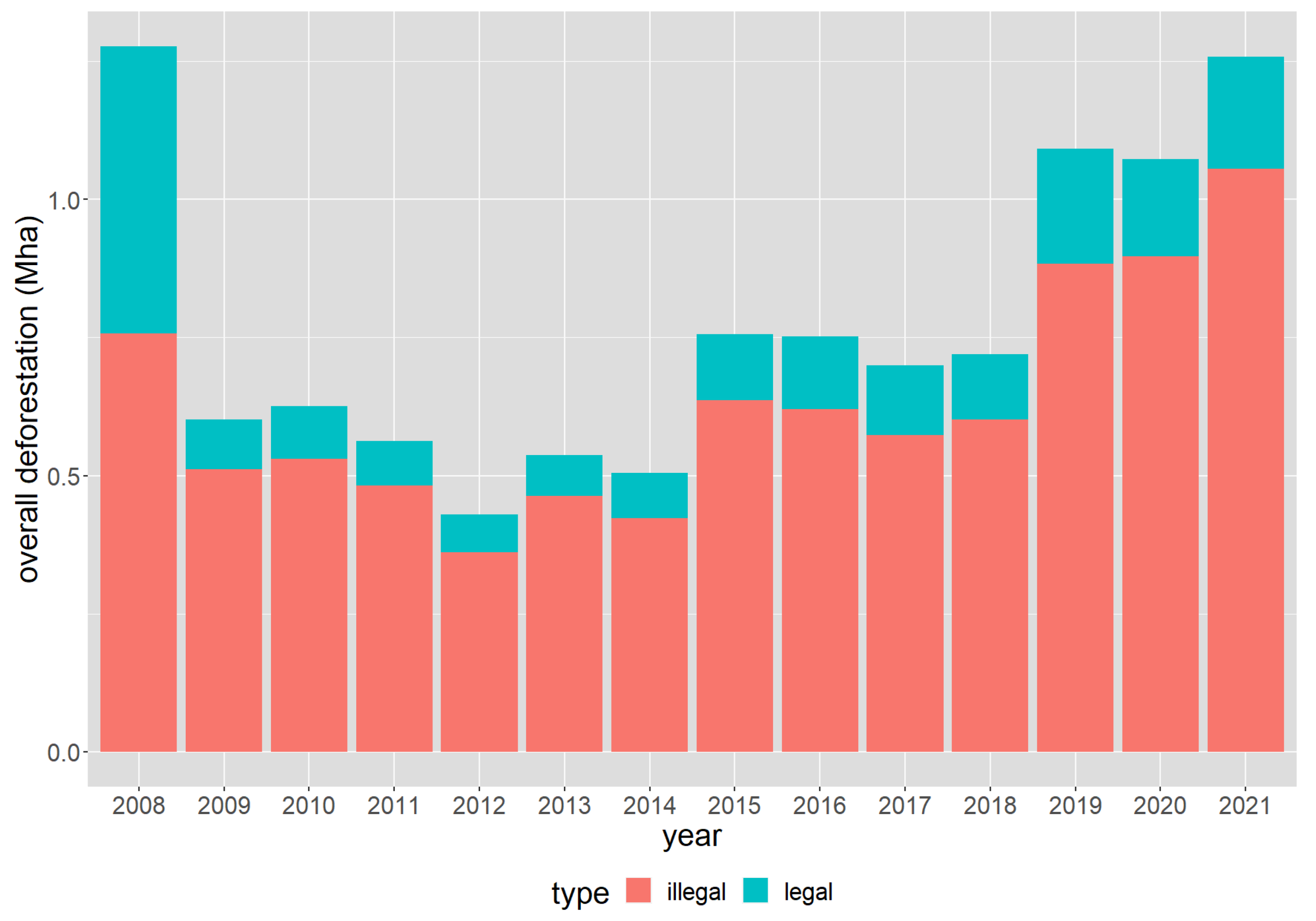

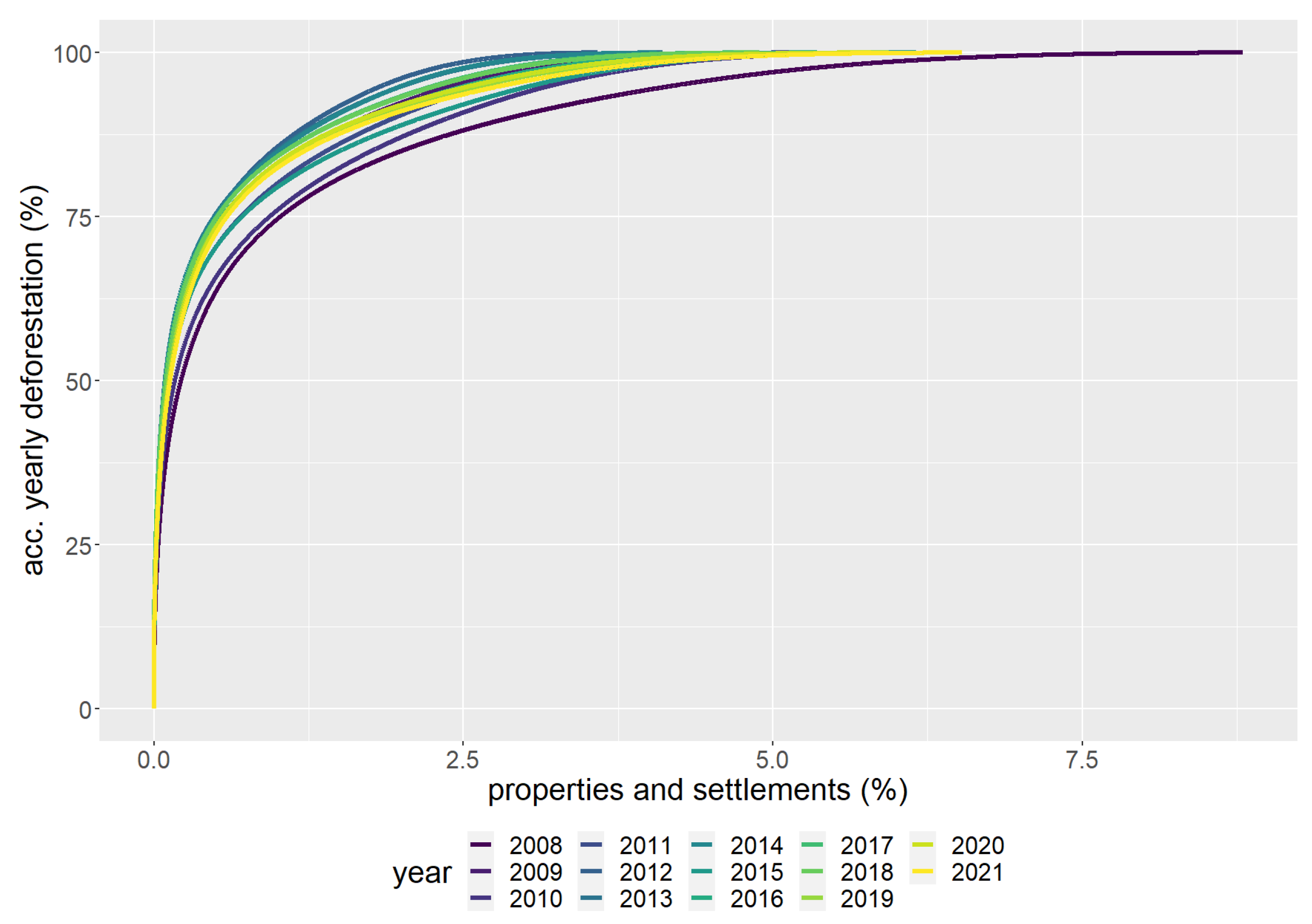

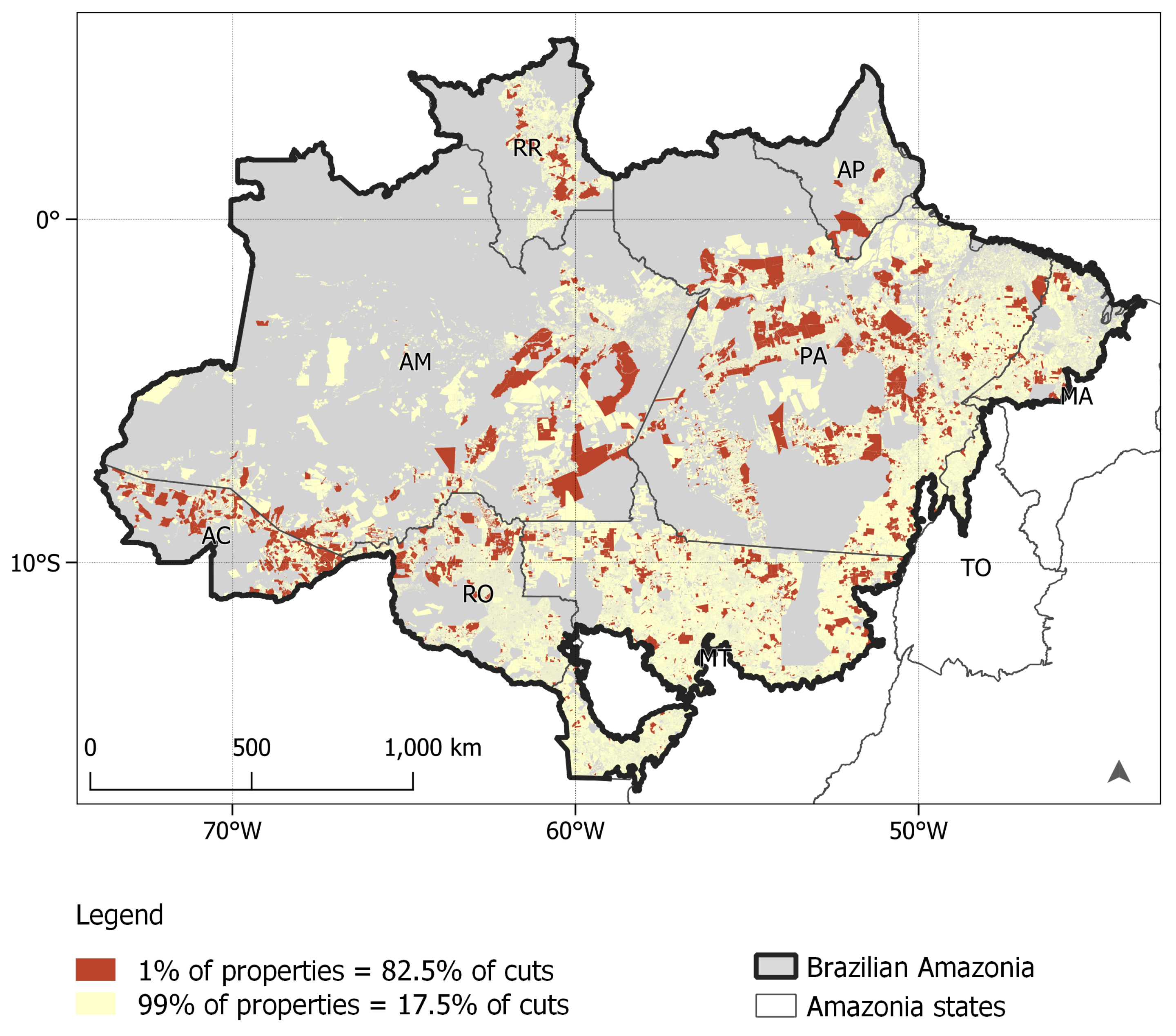

4.1. Trends in Deforestation in Amazonia: 2008-2021

- (i)

- Inside fully protected areas or indigenous lands, deforestation is illegal.

- (ii)

- In undesignated public areas and sustainable conservation units outside the private land tenure map, deforestation is illegal.

- (iii)

- Rural properties inside sustainable conservation units have to abide by an 80% legal reserve limit.

- (iv)

- Other rural properties and settlements can only cut forests legally if they respect the legal reserve limit and do not remove areas of permanent preservation.

4.2. Estimating Opportunity Costs of Forest Restoration

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- INPE. Amazon Deforestation Monitoring Project (PRODES). Technical report, National Institute for Space Research, Brazil, 2022.

- Chiavari, J.; Lopes, C.L. Forest and Land Use Policies on Private Lands: An International Comparison. Technical report, Climate Policy Initiative / PUC-Rio, 2017.

- Soterroni, A.C.; Mosnier, A.; Carvalho, A.X.Y.; Camara, G.; Obersteiner, M.; Andrade, P.R.; Souza, R.C.; Brock, R.; Pirker, J.; Kraxner, F.; Havlik, P.; Kapos, V.; Ermgassen, E.; Valin, H.; Ramos, F.M. Future Environmental and Agricultural Impacts of Brazil’s Forest Code. Environmental Research Letters 2018, 13, 074021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavari, J.; Lopes, C.; Araujo, J. Onde Estamos Na Implementação Do Código Florestal? Radiografia Do CAR e Do PRA Nos Estados Brasileiros (Implementation of Forest Code - Current Status). Technical report, Climate Policy Initiative / PUC-Rio, 2021.

- Soares-Filho, B.; Rajao, R.; Macedo, M.; Carneiro, A.; Costa, W.; Coe, M.; Rodrigues, H.; Alencar, A. Cracking Brazil’s Forest Code. Science 2014, 344, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajão, R.; Soares-Filho, B.; Nunes, F.; Börner, J.; Machado, L.; Assis, D.; Oliveira, A.; Pinto, L.; Ribeiro, V.; Rausch, L.; Gibbs, H.; Figueira, D. The Rotten Apples of Brazil’s Agribusiness. Science 2020, 369, 246–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidotti, V.; Ferraz, S.F.d.B.; Pinto, L.F.G.; Sparovek, G.; Taniwaki, R.H.; Garcia, L.G.; Brancalion, P.H.S. Changes in Brazil’s Forest Code Can Erode the Potential of Riparian Buffers to Supply Watershed Services. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabile, M.C.C.; Guimarães, A.L.; Silva, D.S.; Ribeiro, V.; Macedo, M.N.; Coe, M.T.; Pinto, E.; Moutinho, P.; Alencar, A. Solving Brazil’s Land Use Puzzle: Increasing Production and Slowing Amazon Deforestation. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brites, A.; Mello, K. O Avanco Da Implementacao Do Codigo-Florestal No Brasil (Progress in Forest Code Implementation in Brazil). Technical report, Observatorio do Codigo Florestal, 2021.

- CSR. Panorama Codigo Florestal Brasileiro (Status of Brazil’s Forest Code). Technical report, Centro de Sensoriamento Remoto, UFMG, 2022.

- Drummond, J.A.; Franco, J.L.d.A.; Ninis, A.B. Brazilian Federal Conservation Units: A Historical Overview of Their Creation and of Their Current Status. Environment and History 2009, 15, 463–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foresta, R.A. Amazonia and the Politics of Geopolitics. Geographical Review 1992, 82, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.S.A.d.P.; dos Santos, V.J.; Alves, S.d.C.; Amaral e Silva, A.; da Silva, C.G.; Calijuri, M.L. Contribution of Rural Settlements to the Deforestation Dynamics in the Legal Amazon. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparovek, G.; Reydon, B.P.; Guedes Pinto, L.F.; Faria, V.; de Freitas, F.L.M.; Azevedo-Ramos, C.; Gardner, T.; Hamamura, C.; Rajão, R.; Cerignoni, F.; Siqueira, G.P.; Carvalho, T.; Alencar, A.; Ribeiro, V. Who Owns Brazilian Lands? Land Use Policy 2019, 87, 104062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.A.; Rajão, R.; Costa, M.A.; Stabile, M.C.C.; Macedo, M.N.; dos Reis, T.N.P.; Alencar, A.; Soares-Filho, B.S.; Pacheco, R. Limits of Brazil’s Forest Code as a Means to End Illegal Deforestation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 7653–7658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockendorff, C.; Fuss, S.; Agra, R.; Guye, V.; Herrera, D.; Kraxner, F. Committed to Restoring Tropical Forests: An Overview of Brazil’s and Indonesia’s Restoration Targets and Policies. Environmental Research Letters 2022, 17, 093002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo-Ramos, C.; Moutinho, P.; Arruda, V.L.d.S.; Stabile, M.C.C.; Alencar, A.; Castro, I.; Ribeiro, J.P. Lawless Land in No Man’s Land: The Undesignated Public Forests in the Brazilian Amazon. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.; Coutinho, A.; Esquerdo, J.; Adami, M.; Venturieri, A.; Diniz, C.; Dessay, N.; Durieux, L.; Gomes, A. High Spatial Resolution Land Use and Land Cover Mapping of the Brazilian Legal Amazon in 2008 Using Landsat-5/TM and MODIS Data. Acta Amazonica 2016, 46, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMBRAPA. SIAGEO Amazônia (Sistema Interativo de Análise Geoespacial Da Amazônia Legal). https://www.amazonia.cnptia.embrapa.br/, 2022.

- Souza Jr, C.M.; Z. Shimbo, J.; Rosa, M.R.; Parente, L.L.; A. Alencar, A.; Rudorff, B.F.T.; Hasenack, H.; Matsumoto, M.; G. Ferreira, L.; Souza-Filho, P.W.M.; de Oliveira, S.W.; Rocha, W.F.; Fonseca, A.V.; Marques, C.B.; Diniz, C.G.; Costa, D.; Monteiro, D.; Rosa, E.R.; Vélez-Martin, E.; Weber, E.J.; Lenti, F.E.B.; Paternost, F.F.; Pareyn, F.G.C.; Siqueira, J.V.; Viera, J.L.; Neto, L.C.F.; Saraiva, M.M.; Sales, M.H.; Salgado, M.P.G.; Vasconcelos, R.; Galano, S.; Mesquita, V.V.; Azevedo, T. Reconstructing Three Decades of Land Use and Land Cover Changes in Brazilian Biomes with Landsat Archive and Earth Engine. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 2735. [CrossRef]

- Rosim, S.; Rennó, C.D. TerraHidro: A Distributed Hydrology Modelling System With High Quality Drainage Extraction. GEOProcessing 2013: The Fifth International Conference on Advanced Geographic Information Systems, Applications, and Services, 2013, p. 7.

- da Costa, F.R.; de Souza, R.F.; da Silva, S.M.P. Análise comparativa de metodologias aplicadas à delimitação da bacia hidrográfica do Rio Doce - RN (Comparative analysis of methodologies applied to the demarcation of the basin of Rio Doce - RN). Sociedade & Natureza 2016, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, A.; Camara, G.; Escada, I. Spatial Statistical Analysis of Land-Use Determinants in the Brazilian Amazonia: Exploring Intra-Regional Heterogeneity. Ecological Modelling 2007, 209, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schielein, J.; Borner, J. Recent Transformations of Land-Use and Land-Cover Dynamics across Different Deforestation Frontiers in the Brazilian Amazon. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, D.C.; Benayas, J.M.R.; Ferreira, G.C.; Santos, S.R.; Schwartz, G. An Overview of Forest Loss and Restoration in the Brazilian Amazon. New Forests 2021, 52, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl, C.; Buschbacher, R.; Serrao, E.A.S. Abandoned Pastures in Eastern Amazonia. I. Patterns of Plant Succession. Journal of Ecology 1988, 76, 663–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.V.; Stehman, S.V.; Smith-Rodriguez, K.; Okpa, C.; Aguilar, R. Types and Rates of Forest Disturbance in Brazilian Legal Amazon, 2000–2013. Science Advances 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picoli, M.C.A.; Rorato, A.; Leitão, P.; Camara, G.; Maciel, A.; Hostert, P.; Sanches, I.D. Impacts of Public and Private Sector Policies on Soybean and Pasture Expansion in Mato Grosso—Brazil from 2001 to 2017. Land 2020, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börner, J.; Wunder, S. Paying for Avoided Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon: From Cost Assessment to Scheme Design. International Forestry Review 2008, 10, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.d.F.; Perrin, R.K.; Fulginiti, L.E. The Opportunity Cost of Preserving the Brazilian Amazon Forest. Agricultural Economics 2019, 50, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, M.M.; Uhl, C. Economic and Ecological Perspectives on Ranching in the Eastern Amazon. World Development 1994, 22, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.; Ramos Filho, F.S.V.; Mallmann, G.M.; Fonseca, F. Costs, Benefits and Challenges of Sustainable Livestock Intensification in a Major Deforestation Frontier in the Brazilian Amazon. Sustainability 2017, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spera, S.A.; Cohn, A.S.; VanWey, L.K.; Mustard, J.F.; Rudorff, B.F.; Risso, J.; Adami, M. Recent Cropping Frequency, Expansion, and Abandonment in Mato Grosso, Brazil Had Selective Land Characteristics. Environmental Research Letters 2014, 9, 064010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- zu Ermgassen, E.K.H.J.; Ayre, B.; Godar, J.; Lima, M.G.B.; Bauch, S.; Garrett, R.; Green, J.; Lathuillière, M.J.; Löfgren, P.; MacFarquhar, C.; Meyfroidt, P.; Suavet, C.; West, C.; Gardner, T. Using Supply Chain Data to Monitor Zero Deforestation Commitments: An Assessment of Progress in the Brazilian Soy Sector. Environmental Research Letters 2020, 15, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, P.H.; Bernasconi, P.; Wunder, S.; Lubowski, R. Environmental Reserve Quotas in Brazil’s New Forest Legislation: An Ex Ante Appraisal. Technical report, Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), 2015. [CrossRef]

| Type | Description | Source | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Indigenous lands | FUNAI | 2021 |

| land tenure | Conservation units | ICMBIO | 2021 |

| Quilombola lands | INCRA | 2021 | |

| Rural settlements | INCRA | 2021 | |

| Undesignated | CNFP | 2016 | |

| public forests | |||

| Private | SIGEF (rural properties) | INCRA | 2021 |

| land tenure | SNCI (rural properties) | INCRA | 2021 |

| Terra Legal (rural properties) | INCRA | 2019 | |

| CAR (Self-declared | SFB | 2021 | |

| environmental cadastre) | |||

| Land use and | PRODES (deforestation) | INPE | 2021 |

| land cover | MapBiomas 1985–1998 | MapBiomas | 2022 |

| TerraClass | INPE/Embrapa | 2020 | |

| Ecological | SIAGEO (areas where | Embrapa | 2022 |

| economic zones | legal reserve is reduced) |

| Category | Amount | Total Area (Mha) |

|---|---|---|

| Indigenous lands | 357 | 108.6 |

| Quilombola lands | 128 | 1.7 |

| Fully protected conservation units | 116 | 35.7 |

| Sustainable use conservation units | 232 | 41.2 |

| Military use | 1 | 2.2 |

| Undesignated public forests | 61.6 | |

| Total | 251.0 |

| Farm Type | Farm Size | Total Forest (Mha) | Deficit (Mha) | Surplus (Mha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private | 0-200 ha | 19.0 | 0.99 | 0.48 |

| properties | 200-1000 ha | 22.8 | 3.81 | 1.55 |

| > 1000 ha | 65.1 | 7.67 | 8.20 | |

| Settlements | 30.6 | 5.70 | 2.26 | |

| Total | 137.5 | 18.17 | 12.49 |

| Land use | Farm type | Farm Size (ha) | Area (Mha) | Deficit (Mha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary | private | 0-200 | 1.29 | 0.10 |

| forests | 200-1000 | 1.15 | 0.32 | |

| > 1000 | 2.07 | 0.65 | ||

| settlements | 1.35 | 0.51 | ||

| Total | 5.86 | 1.58 | ||

| Herbaceous | private | 0-200 | 7.68 | 0.59 |

| pasture | 200-1000 | 6.80 | 2.28 | |

| > 1000 | 10.69 | 4.45 | ||

| settlements | 7.66 | 3.57 | ||

| Total | 32.83 | 10.89 | ||

| Shrubby | private | 0-200 | 2.65 | 0.26 |

| pasture | 200-1000 | 1.84 | 0.60 | |

| > 1000 | 2.63 | 0.89 | ||

| settlements | 3.50 | 1.37 | ||

| Total | 10.62 | 3.12 | ||

| Single-crop | private | 0-200 | 0.10 | 0.01 |

| farming | 200-1000 | 0.20 | 0.08 | |

| > 1000 | 0.37 | 0.16 | ||

| settlements | 0.07 | 0.03 | ||

| Total | 0.74 | 0.28 | ||

| Multi-crop | private | 0-200 | 0.50 | 0.02 |

| farming | 200-1000 | 1.30 | 0.45 | |

| > 1000 | 2.76 | 1.37 | ||

| settlements | 0.27 | 0.19 | ||

| Total | 4.83 | 2.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).