1. Introduction

Despite the significant progress in medical care over the past decades, typical high rates of death related to aortic dissection continue to be a crucial issue [

1,

2]. Although intraoperative mortality has decreased, post-operative mortality continues to remain high due to comorbidities [

1,

3]. Usually, pre-anesthetic screening is not performed on patients with acute symptoms, which is essential for identifying and excluding comorbidities that can influence the patient's outcomes [

4].

For high-quality care, it is of crucial importance to understand which factors decrease the mortality rate in aortic diseases. Since treatment is usually provided to the affected segment of the aorta only, leaving the rest of the aorta at risk, it is essential to have a deep understanding of the disease's etiology [

5,

6].

With increased experience in aortic disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment protocols, mortality rates has significantly decreased [

7,

8,

9]. However, to provide surgical treatment and protect the patient from suffering additional complications, an early diagnosis is necessary [

10,

11]. While at present survival rates continue to increase, mortality rates remain high for unknown reasons. These factors may have a significant impact on the outcome of the patients if they are identified and treated successfully [

12,

13].

Recent studies showed that one of the key factors that influence overall patient survival is the patients' admission day, during the weekend or weekday [

14,

15,

16]. Notwithstanding the availability of the healthcare system during the weekends, it is shown that patients who receive treatments on weekends have higher morbidity and mortality rates [

17,

18]. This might be a consequence of a more limited diagnostic investigation typical of weekends as compared to a weekday. As a consequence, it is more difficult both to identify the underlying medical condition of the patients and to successfully implement therapeutic preventive measures meant to decrease immediate mortality.

Whether a patient is admitted to the hospital during the week or the weekend, the timing of their presentation is an important factor that should not be ignored and deserves further investigation. The absence of medical professional workers throughout the weekend can cause a delay in treatment for patients suffering thoracic aorta injury, justifying the demand for this study. The various levels of experience among health professionals should also be taken into account as they may have a negative impact on treatment outcomes [

19]. Before surgery, in particular, it is essential to identify potential risk factors and adopt initiatives to improve patient outcomes. It is hard to overestimate how crucial this is, and it deserves ongoing attention [

20].

Regardless of the day of hospital admission, maintaining stability in AD is vital for effective treatment. The purpose of this research is to compare the outcome of the patients treated on weekdays to those treated on weekends to determine whether a difference in mortality before, during, and after invasive treatment for aortic dissection can be observed. A prospective analysis is here performed on the hospital records of patients who received surgical treatment for AD in a single cardiac surgery department. In this study, a variety of statistical methods are employed to investigate the predictability of the day of admission as a risk factor for AD. The paper is organized as follows. In section 2, we describe the material used and the methods employed here. Then in section 3, we present the statistical results on the so-called "weekend effect" for AD treatment, while an extensive discussion on the outcome is made in section 4. The article closes with the conclusions in section 6, after highlighting some some limits of the study in section 5.

2. Materials and Methods

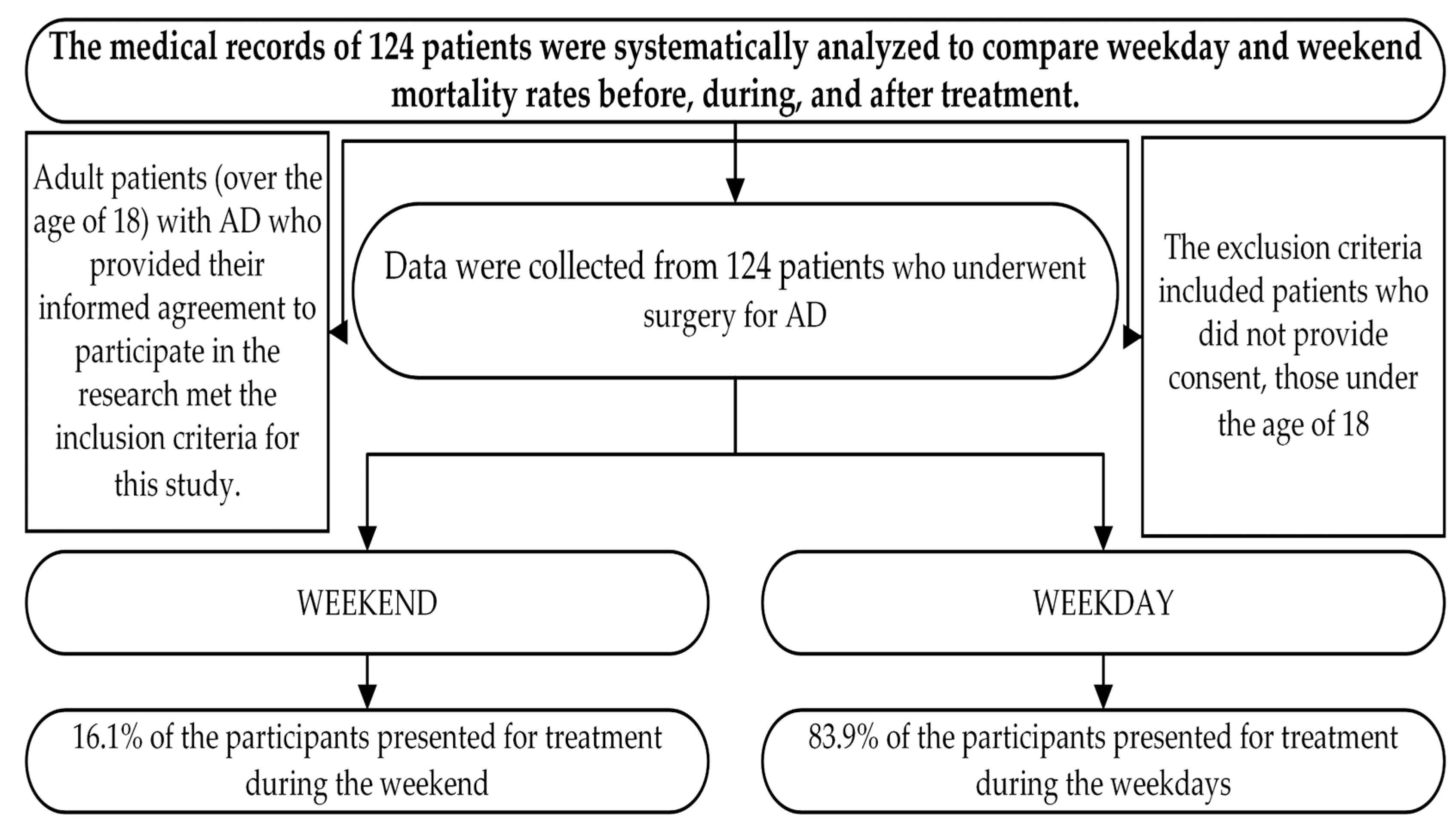

This study aims to assess the relationship between the day of the week and mortality in patients undergoing invasive treatment for AD. Medical records of 124 patients were prospectively examined to determine the mortality rates before, during, and after treatment, as well as between weekdays and weekends (

Figure 1). To assess if the period of admission during the week may have an impact on the outcome of AD, the study analyzed medical data collected in a single tertiary cardiac surgery center between 2019 and 2021, with a six-month follow-up.

The inclusion criteria for this study were adult patients (over the age of 18) presenting with AD, who gave their informed consent to participate in the study. The patients were treated on a 7-day/week basis. The exclusion criteria included patients who did not provide consent, those under the age of 18, and patients admitted to the hospital with associated medical comorbidities such as chronic congestive heart failure (HYHAIII–IV) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) use preoperatively, and those who required treatment for chronic heart diseases on either weekdays or weekends. All patient data were analyzed following ethical standards, intensive care unit (ICU) protocols, and standard surgical operating protocols.

Statistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics program (IBM Corp. Released 2015. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 16.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp., USA). When dealing with categorical variables, the findings of descriptive statistics were often reported in the form of absolute and relative frequencies. The mean ± standard deviation (minimum-maximum) was used for continuously collected data.

The study provides an in-depth overview of the participants’ clinical and baseline characteristics, which can provide valuable insights into the factors that might have influenced their outcomes.

3. Results

The participants of the study were 124 patients who underwent surgery for AD. (See

Figure 1)

In particular, 67.7% of the participants were men and 32.3% were women. The majority of the participants presented for treatment during the weekdays (83.9%), while only 16.1% presented during the weekend. Based on this analysis, 40 (32.3%) of the patients had hemopericardium, 18 (14.5%) had cardiac tamponade, 13 (10.5%) had cardiogenic shock, and 2 (1.6%) had cardiac arrest, 3 (2.4%) were on anticoagulation therapy and 19 (15.3%) were on antiplatelet therapy, 60.5% of the patients underwent ascending aorta replacement, 8.9% underwent hemiarch replacement, 19.4% underwent aortic valve replacement, 7.3% underwent RCA reimplantation, 6.5% had LCA reimplantation, 3.2% LAD bypass, 5.6% RCA bypass, and 5.6% Bentall procedure. Before surgery, 3 (25%) patients died, and 12 (9.7%) patients died in the hospital. A total of 52 (41.9%) patients died during the study, and 10 (8.1%) of these deaths were immediate. The observations presented here are summarized in

Table 1.

In the following, the average laboratory data of the patients at admission time considered in this study is presented (

Table 2). The study population had a mean age of 62.5 years with a high degree of variability. On average the population had a LVEF value of 51.05% with high variability, while the creatinine levels showed low variability with a mean of 1.25 mg/dl, value at the limit of normal reference range. eGFR had a mean of 71.30 mL/min/1.73m

2, within normal boundaries but with high variability. Liver function (GOT and GPT) showed high variability with mean levels of 79.82 U/L and 71.13 U/L, beyond the standard reference range. Hemoglobin levels had a mean of 12.50 g/dl, slightly below range with low variability. Platelet count had a mean of 224.92 × 103/uL in normal parameters but with high variability. White blood cell count had a mean of 11.33 × 103/uL, at standard conditions with low variability, see

Table 2.

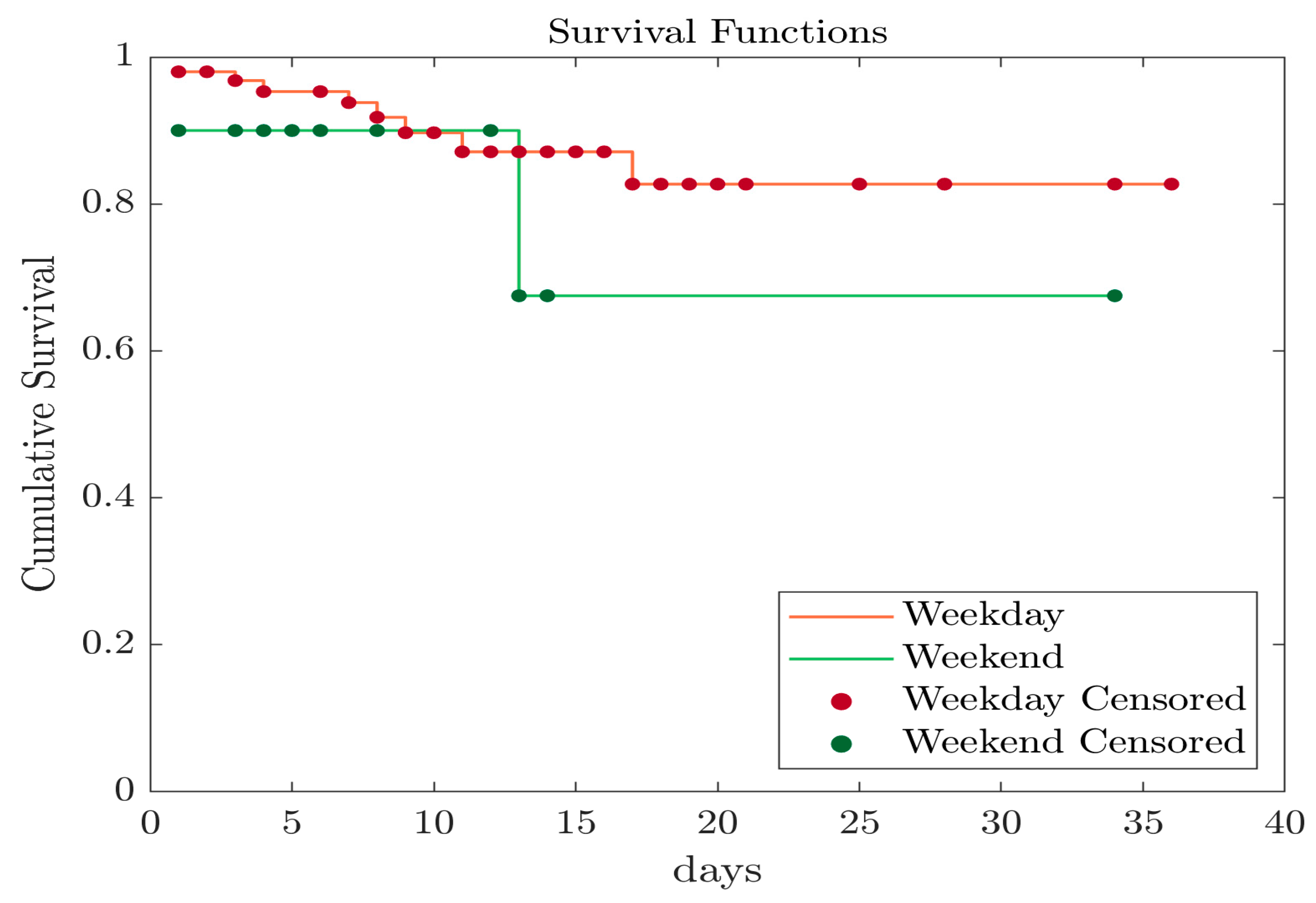

In the following Kaplan-Meier survival analyses for both weekday and weekend groups of populations are presented. In

Figure 2, we show results of survival analysis before surgery. As can be seen, both groups exhibit similar survival curves with no particular difference in their trends.

In

Table 3, mortality events before surgical intervention are summarized. The weekend group comprised 104 patients, with 9 death events recorded, resulting in a death event percentage of 8.65%. The weekday group consisted of 20 patients, with 3 death events recorded, equating to a death event percentage of 15%. To evaluate the significance of these results three statistical tests were applied, but no statistical difference between the analyzed weekend and weekday groups, see

Table 3.

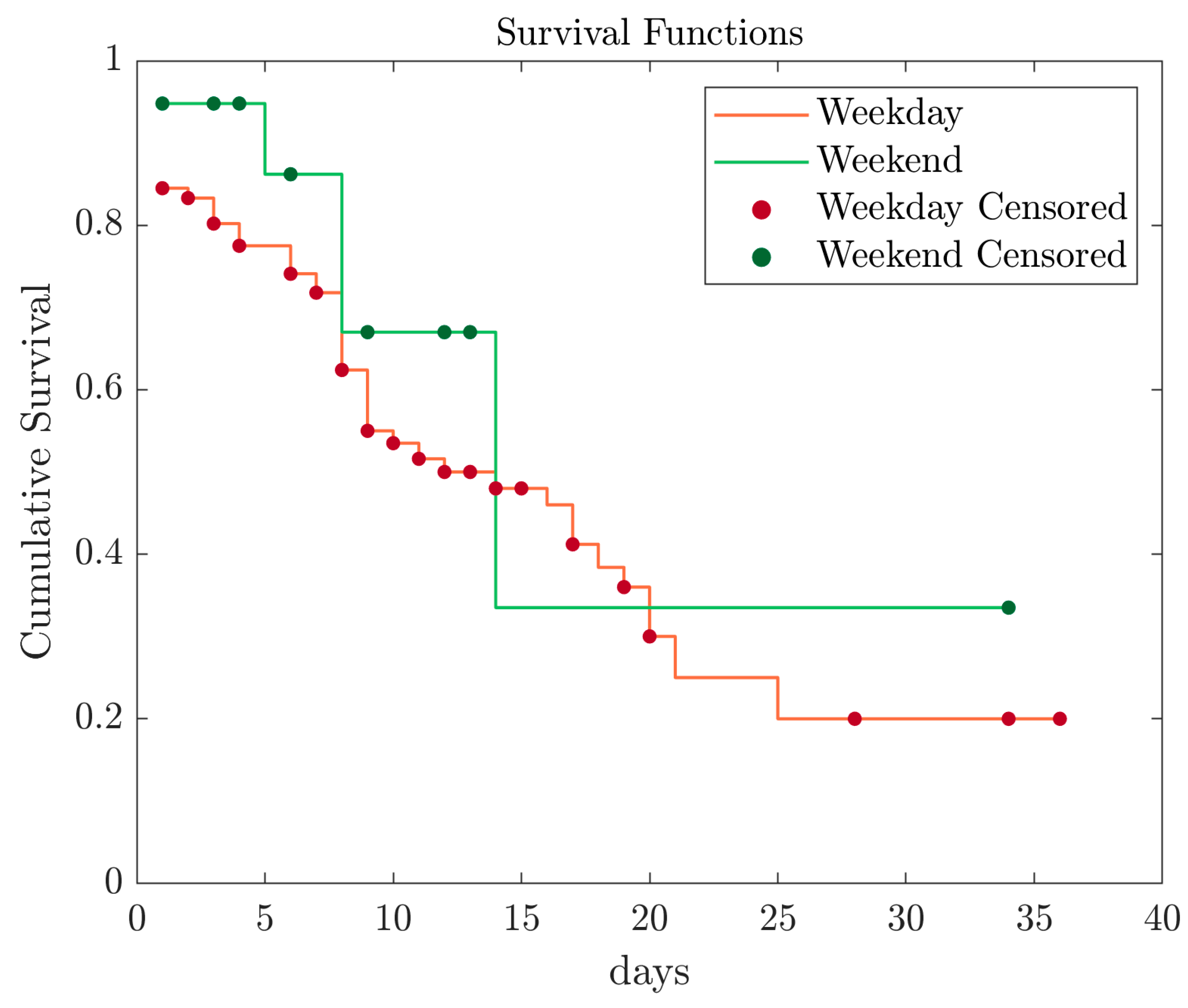

In the following, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis is used to compare in-hospital mortality rates between weekday and weekend patients. The results indicated that both patient groups presented a similar statistical pattern, highlighted by a comparable downward trend in their survival probability (

Figure 3).

The results of the study of in-hospital mortality data, including the number of patients, death events, and death event percentage, for both the weekend and weekday groups, are summarized in

Table 4. The weekend group consisted of 104 patients, 52 death events, and a death event percentage of 50%. The weekday group comprised 20 patients, with 5 death events and a death event percentage of 25%. For patients who were admitted to the hospital on weekdays and passed away during their hospital stay, the mean time to death was 15.8 days (95% CI, 12.7 to 18.9). For patients who were admitted to the hospital on weekend and passed away during their hospital stay the mean time to death was 18.1 days (95% CI, 7.7 to 28.6). Log Rank (Mantal-Cox), Breslow (Generalized Willcoxon), and Tarone Ware tests were performed to determine if there are any differences in mortality rates between patients admitted to the hospital on weekends compared to those admitted on weekdays. No statistically significant differences were found between these two groups regarding in-hospital mortality, (see

Table 4).

Regarding immediate mortality data, in the weekend group, there were 104 patients, with 10 death events resulting in a death event percentage of 9.61%. The weekday group comprised 20 patients, with 1 death event resulting in a death event percentage of 5%. For patients who were admitted to hospital during weekdays, received surgical treatment and passed away in the follow-up period, the mean time to death was 29.5 days (95% CI, 25.7 to 33.2). For patients who were admitted to hospital during the weekend, received surgical treatment and passed away in the follow-up period, the mean time to death was 34 days (95% CI, 34 to 34).

The analysis performed to determine if there were differences between weekend and weekday groups, mortality registered in the follow-up period shows no statistically significant differences between them, (see

Table 5). In this case, no Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was conducted given the reduced sample size which does not allow for consistent conclusions.

4. Discussion

The patient's life is immediately affected by the catastrophic cardiovascular condition of aortic dissection. Understanding every factor that directly affects mortality rates is important since the timing of a patient's admission to a hospital can have a significant impact on the course of treatment [

21].

It is still necessary to identify other risk factors that might increase mortality rates besides the severity of aortic disease and its direct impact on treatment outcomes. Previous research has made an effort to investigate the link between acute or chronic patients and arrival times at the medical facility, such as on weekends or weekdays, without general agreement [

22,

23,

24].

In this study, the majority of the patients were male and presented for treatment during the weekdays. The results showed that patients with more complicated pathologies such as hemopericardium, cardiac tamponade, cardiogenic shock, and cardiac arrest were more likely to experience adverse outcomes. Additionally, the presence of anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy added another layer of complexity to the patient’s condition and may have contributed to the higher mortality rate observed in the study. The surgical interventions performed in this study included ascending aorta replacement, hemiarch replacement, aortic valve replacement, RCA and LCA reimplantation, myocardial revascularization and Bentall procedure. The analysis indicates that in-hospital mortality rate was higher than in follow-up. It is important to note the impact of the pathological complexity of these patients on both the surgical intervention and the outcome. Understanding these complexities is crucial in improving patient care and outcomes in cases of aortic dissection

The associated medical condition could negatively affect patients' outcomes whether they receive elective or emergency aortic surgery, or if they receive it on a weekday or a weekend [

25].

Aortic dissection has been associated with a variety of etiological factors, such as male gender, age, genetics, hypertension, aortic valve diseases, or abnormalities of collagen tissue, age [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Knowing this makes it possible to take action against the condition, extend patient monitoring for those who are susceptible, develop particular therapeutic approaches, and prepare patients for elective treatments when they meet the criteria for surgical indication.

Understanding the health status and the need for additional intervention largely depends on the conclusions of the analysis. The results indicated that the studied population's average age was high and that there was a significant level of individual age variability. Multiple factors, including genetics, lifestyle, and overall health, could be responsible for the age range level [

30].

LVEF, which measures how efficiently the heart can pump blood, had a high standard deviation, which indicates a high level of variability. LVEF variation may be caused by a variety of conditions, such as aging, heart disease, or cardiovascular disease.

With a mean value and a low standard deviation, the creatinine levels in the study population showed low variability. This might indicate that the studied population's kidney function is at a comparable level. The estimated glomerular filtration rate, on the other hand, showed a high standard deviation, indicating a high level of variability in this parameter, which may be caused by several factors affecting kidney function. The liver function parameters showed high variability, which could be a result of various factors affecting liver function. A similar level of hemoglobin production in the study population is suggested by the low standard deviation of hemoglobin levels. The platelet count, on the other hand, had a high standard deviation, indicating a high degree of variability in this parameter, which may be caused by a variety of factors that influence blood clotting. The white blood cell count also had a low standard deviation, indicating that the research population generated white blood cells at a similar rate. The findings of our study reveal information on the health of the group under observation and highlight the necessity for additional research to fully comprehend how these characteristics affect the prognosis of individuals with similar diseases.

Even if a genetic diagnosis does not exist, the pathogenesis may point to different genetic syndromes like Marfan syndrome and Ehrle-Danlos due to the disease's agelessness and premature development. Furthermore, this could be alert for long-term conditions such as atherosclerosis or uncontrolled hypertension, making it an important factor that should not be overlooked [

31].

As aortic dissection has a high death rate—an estimated 50% during the first hour of onset—constant worry about the condition is essential [

32]. This accentuates the urgency and importance of the condition since there is a good chance the patient will not arrive at hospital in time for prompt and effective treatment.

In particular, the occurrence of preoperative and postoperative events must be taken into account when analyzing mortality and its reduction in relation to inpatient and outpatient care. To identify and manage risk factors and circumstances that could influence a hospitalized patient's mortality, this evaluation is required [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Due to the high rate of death associated with this disease, the treatment approach in the case of an emergency presentation of a patient with an aortic dissection must be concentrated on the segments that are eligible for therapeutic intervention. Early recognition and treatment of known risk factors in these circumstances may make the difference between life and death [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42].

The results of the statistical analysis failed to show a significant difference between the mortality events before surgical intervention that occurred in the weekend group and the weekday group. The three tests used (Log Rank (Mantal-Cox), Breslow (Generalized Willcoxon), and Tarone Ware) yielded p-values greater than 0.05, indicating a lack of statistical significance in the difference in death event percentage between the two groups. Although the percentage of death events was higher in the weekday group, the results of the analysis do not support the notion that this difference is statistically significant.

It is well documented that patients who arrive for elective treatment are managed better and have a higher chance of surviving than patients who arrive for emergency medical care. The affected aorta segment must always be identified to determine the best treatment strategy and establish any associated diseases and risk factors [

43,

44].

The patient could develop hemodynamic instability while being transferred to the cardiac surgery department, which may increase overall mortality [

45,

46].

The results of our data analysis, which examined the association between in-hospital death rates and admission periods (weekend vs. weekday), revealed no statistically significant difference in the mortality rates between the two groups. We also looked into the link between admission times and immediate mortality (death within six months after release). The findings indicate that there is no relationship between the day of admission and the mortality rate, but further research is needed to prove or disprove these results and determine the underlying reasons for the correlation. This study provides valuable insights into in-hospital mortality patterns and has the potential to inform future research and medical practices aimed at improving knowledge of patient outcomes.

Based on the findings of the current study, there were no significant differences in in-hospital mortality rates among patients with aortic dissection who arrived on weekends versus those who arrived on weekdays. This indicates that the cause of death rate observed in these diseases is complex and multifactorial and that more research is required to determine and tackle the real factors. These findings shed a light on the need for a comprehensive understanding of the risk factors, clinical procedures, and types of surgery attributed to AD to provide consistent and optimal patient outcomes each day of the week. These observations, along with those from previous research, provide critical guidelines for public study in order to identify fresh, undiscovered risk variables that affect aortic dissection patients. These findings support ongoing efforts to improve patient outcomes as well as our knowledge of this complex disease, given that aortic dissection is a potentially fatal disorder that continues to inspire great interest and research in the medical community.

5. Limitations

It is important to note that the study presented here was limited by the exclusion of patients who died before hospitalization, which may have impacted the overall results. Additionally, the study was conducted in a single cardiac surgery department, which may not fully reflect the larger population while the absence of national prevention programs adds to the complexity of this field. The limited follow-up period of six months after surgery, as determined by the national registry, also presents a challenge for long-term analysis.

6. Conclusions

The results of the present study indicate that there is no significant difference in mortality between patients diagnosed with aortic dissection who present on weekends versus weekdays. This finding emphasizes the crucial need for consistent and uniform high-quality medical care, regardless of the day of presentation. To further advance the field and enhance our understanding of these life-threatening diseases, it is imperative to continue investigating the factors that influence surgical outcomes. This objective can be achieved through conducting multicenter studies, which will broaden the scope and depth of analysis beyond the limitations of a single cardiac surgery center. In addition, the establishment of national registers and the implementation of preventative programs could contribute to reducing the mortality rate associated with aortic dissection, which remains a topic of ongoing investigation. Despite the limitations, the results of the current study contribute to the advancement of the knowledge base in the field and provide a foundation for future studies to build upon, particularly regarding the identification of new risk factors and improvement of outcomes for patients with aortic dissection. This study provides valuable insights into the mortality rate of aortic dissection and has the potential to inform future research and medical practices, shedding light on crucial areas for improving patient outcomes and shaping effective treatment strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B., H.S. and M.H.; methodology, S.H.; K.B.; N.N.; and D.A.S.; software, M.N.H.; D.A.S.; and C.B; validation, C.B., H.S; K.B.; M.H.; N.N.; D.A.S.; D.B.; M.O.; H.A.H.; D.C; A.S; and M.N.H.; formal analysis, C.B., H.S.; M.N.H.; and M.H.; investigation, C.B.; H.S.; M.H.; D.B.; D.C.; A.S.; and H.A.H.; resources, C.B.; M.H.; H.S.; D.B.; D,C.; H.A.H.; M.O.; and A.S.; data curation, C.B.; M.H.; and H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.B.; and M.H.; writing—review and editing, K.B.; M.N.H.; N.N.; and D.A.S.; visualization, C.B., H.S. and M.H; supervision, H.S.; K.B.; and M.N.H.; project administration, C.B., H.S. and M.H.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study adhered to the ethical standards established by the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by both the Emergency Institute for Cardiovascular Diseases and Transplant in Târgu Mureș and the George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science, and Technology in Târgu Mureș (UMFST) Mureș—via resolutions 7225/07.10.2019, 878/23.04.2020, and 1359/10.05.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to my scientific supervisor, Professor Radu Deac, Faculty of Medicine at the George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science, and Technology of Targu Mures, 540139 Targu Mures, Romania for his constant guidance, support, professional advice and encouragement throughout elaboration of this research and to Professor Anisoara Pop, Faculty of Medicine at the George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science, and Technology of Targu Mures, 540139 Targu Mures, Romania, for her invaluable guidance, unflagging support and extensive personal advice. They have given me a lot of scientific understanding about scientific research, which makes me extremely grateful.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dinh, M.M., Bein, K.J., Delaney, J., Berendsen Russell, S., Royle, T. Incidence and outcomes of aortic dissection for emergency departments in New South Wales, Australia 2017-2018: A data linkage study. Emerg Med Australas 2020, 32(4), 599–603. [CrossRef]

- Thiene, G., Basso, C., Della Barbera, M. Pathology of the Aorta and Aorta as Homograft. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2021, 8(7), 76, Published 2021 Jun 29. [CrossRef]

- Biancari, F., Mariscalco, G., Yusuff, H., et al. European registry of type A aortic dissection (ERTAAD)—rationale, design and definition criteria [published correction appears in J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021 Aug 9;16(1):225]. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021, 16(1), 171, Published 2021 Jun 10. [CrossRef]

- Bonaca, M.P., O’Gara, P.T. Diagnosis and management of acute aortic syndromes: dissection, intramural hematoma, and penetrating aortic ulcer. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014, 16(10), 536. [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.A., Yamamoto, J.M., Roberts, D.J., et al. Weekend Surgical Care and Postoperative Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Med Care. 2018, 56(2), 121–129. [CrossRef]

- Arnaoutakis, G., Bianco, V., Estrera, A.L., et al. Time of day does not influence outcomes in acute type A aortic dissection: Results from the IRAD. J Card Surg. 2020, 35(12), 3467–3473. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A., Fyyaz, S.A., Carter, P.R., Potluri, R. The enigma of the weekend effect. J Thorac Dis. 2018, 10(1), 102–105. [CrossRef]

- Galyfos, G., Sigala, F., Bazigos, G., Filis K. Weekend effect among patients undergoing elective vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2019, 70(6), 2038–2045. [CrossRef]

- Harky, A., Mason, S., Othman, A., et al. Outcomes of acute type A aortic dissection repair: Daytime versus nighttime. JTCVS Open. 2021, 7, 12–20, Published 2021 May 5. [CrossRef]

- Pupovac, S.S., Hemli, J.M., Seetharam, K., et al. Acute Type A Aortic Dissection Repair After Hours: Does It Influence Outcomes? Ann Thorac Surg. 2020, 110(5), 1622–1628. [CrossRef]

- Glance, L.G., Osler, T., Li, Y., et al. Outcomes are Worse in US Patients Undergoing Surgery on Weekends Compared With Weekdays. Med Care. 2016, 54(6), 608–615. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J., Zhang, L., Luo, X., et al. Higher Mortality in Patients Undergoing Nighttime Surgical Procedures for Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018, 106(4), 1164–1170. [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, C.A., Sedrakyan, A., Schwaneberg, T., et al. Impact of weekend treatment on short-term and long-term survival after urgent repair of ruptured aortic aneurysms in Germany. J Vasc Surg. 2019, 69(3), 792–799.e2. [CrossRef]

- Bressman, E., Rowland, J.C., Nguyen, V.T., Raucher, B.G. Severity of illness and the weekend mortality effect: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020, 20(1), 169, Published 2020 Mar 4. [CrossRef]

- Honeyford, K., Cecil, E., Lo, M., Bottle, A., Aylin, P. The weekend effect: does hospital mortality differ by day of the week? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018, 18(1), 870, Published 2018 Nov 20. [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H., Ando, T., Umemoto, T.; ALICE (All-Literature Investigation of Cardiovascular Evidence) group. A meta-analysis of weekend admission and surgery for aortic rupture and dissection. Vasc Med. 2017, 22(5), 398–405. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N., Venkatraman, A., Pandey, A., Khera, R., Garg, N. Weekend hospitalisations for acute aortic dissection have a higher risk of in-hospital mortality compared to weekday hospitalisations. Int J Cardiol. 2016, 214, 448–450. [CrossRef]

- Tolvi, M., Mattila, K., Haukka, J., Aaltonen, L.M., Lehtonen, L. Analysis of weekend effect on mortality by medical specialty in Helsinki University Hospital over a 14-year period. Health Policy. 2020, 124(11), 1209–1216. [CrossRef]

- Gokalp, O., Yilik, L., Besir, Y., et al. "Overtime Hours Effect" on Emergency Surgery of Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2019, 34(6), 680–686, Published 2019 Dec 1. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Yang, G., He, H., Pan, X., Peng, W., Chai, X. Association between admission time and in-hospital mortality in acute aortic dissection patients: A retrospective cohort study. Heart Lung. 2020, 49(5), 651–659. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Lv, W., Liu, X., Liu, K., Yang, S. Impact of shift work on surgical outcomes at different times in patients with acute type A aortic dissection: A retrospective cohort study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022, 9, 1000619, Published 2022 Oct 28. [CrossRef]

- Matoba, M., Suzuki, T., Ochiai, H., et al. Seven-day services in surgery and the "weekend effect" at a Japanese teaching hospital: a retrospective cohort study. Patient Saf Surg. 2020, 14, 24, Published 2020 Jun 4. [CrossRef]

- Groves, E.M., Khoshchehreh, M., Le, C., Malik, S. Effects of weekend admission on the outcomes and management of ruptured aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2014, 60(2), 318–324. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, H.J., Marashi-Pour, S., Chen, H.Y., Kaldor, J., Sutherland, K., Levesque, J.F. Is the weekend effect really ubiquitous? A retrospective clinical cohort analysis of 30-day mortality by day of week and time of day using linked population data from New South Wales, Australia [published correction appears in BMJ Open. 2018 May 14, 8(5), e016943corr1]. BMJ Open. 2018, 8(4), e016943, Published 2018 Apr 12. [CrossRef]

- Panhwar, M.S., Deo, S.V., Gupta, T., et al. Weekend Operation and Outcomes of Patients Admitted for Nonelective Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020, 110(1), 152–157. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M. Pathophysiology of Aortic Dissection and Connective Tissue Disorders. In: Fitridge R, Thompson M, editors. Mechanisms of Vascular Disease: A Reference Book for Vascular Specialists [Internet]. Adelaide (AU): University of Adelaide Press 2011, 14. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534274/.

- Wang, J.X., Xue, Y.X., Zhu, X.Y., et al. The impact of age in acute type A aortic dissection: a retrospective study. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022, 17(1), 40, Published 2022 Mar 19. [CrossRef]

- Son, N., Choi, E., Chung, S.Y., Han, S.Y., Kim, B. Risk of aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection with the use of fluoroquinolones in Korea: a nested case-control study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022, 22(1), 44, Published 2022 Feb 13. [CrossRef]

- Morjan, M., Mestres, C.A., Lavanchy, I., et al. The impact of age and sex on in-hospital outcomes in acute type A aortic dissection surgery. J Thorac Dis. 2022, 14(6), 2011–2021. [CrossRef]

- Bossone, E., Carbone, A., Eagle, K.A. Gender Differences in Acute Aortic Dissection. J Pers Med. 2022, 12(7), 1148, Published 2022 Jul 15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Chen, T., Zhang, Y., et al. Crucial Genes in Aortic Dissection Identified by Weighted Gene Coexpression Network Analysis. J Immunol Res. 2022, 2022, 7585149, Published 2022 Feb 7. [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, K.S., LeGuillan, M.P., Steinmetz, O.K., Montreuil, B. Management trends and early mortality rates for acute type B aortic dissection: a 10-year single-institution experience. Ann Vasc Surg. 2004, 18(2), 158–166. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altujjar, M., Mhanna M., Bhuta, S., Patel N., Miedema, M.D., et al. The weekend effect on outcomes in patients presenting with acute aortic dissection: a nationwide analysis. JACC 2022, 79(9), 1742. [CrossRef]

- Conzelmann, L.O., Weigang, E., Mehlhorn, U., et al. Mortality in patients with acute aortic dissection type A: analysis of pre- and intraoperative risk factors from the German Registry for Acute Aortic Dissection Type A (GERAADA). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016, 49(2), e44–e52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampoldi, V., Trimarchi, S., Eagle, K.A., et al. Simple risk models to predict surgical mortality in acute type A aortic dissection: the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection score. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007, 83(1), 55–61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, A., Tilea, I., Tatar, C.M., et al. Native Aortic Valve Endocarditis Complicated by Splenic Infarction and Giant Mitral-Aortic Intervalvular Fibrosa Pseudoaneurysm-A Case Report and Brief Review of the Literature. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11(2), 251, Published 2021 Feb 6. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.H., Suzuki, T., Hagan, P.G., et al. Predicting death in patients with acute type a aortic dissection. Circulation. 2002, 105(2), 200–206. [CrossRef]

- Kazui, T., Washiyama, N., Bashar, A.H., et al. Surgical outcome of acute type A aortic dissection: analysis of risk factors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002, 74(1), 75–82. [CrossRef]

- Hibino, M., Otaki, Y., Kobeissi, E., et al. Blood Pressure, Hypertension, and the Risk of Aortic Dissection Incidence and Mortality: Results From the J-SCH Study, the UK Biobank Study, and a Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Circulation 2022, 145(9), 633–644. [CrossRef]

- Tilea, I., Petra D., Voidazan S., Ardeleanu E. et al. Treatment adherence among adult hypertensive patients: a cross-sectional retrospective study in primary care in Romania. Patient Preference and Adherence 2018, 12, 625–635. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucera, M., Heinisch, P.P., Langhammer, B., et al. The impact of sex and gender on aortic events in patients with Marfan syndrome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2022, 62(5), 305. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacGillivray, T.E., Gleason, T.G., Patel, H.J., et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American Association for Thoracic Surgery Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Type B Aortic Dissection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022, 113(4), 1073–1092. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trimarchi, S., de Beaufort, H.W.L., Tolenaar, J.L., et al. Acute aortic dissections with entry tear in the arch: A report from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019, 157(1), 66–73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luehr, M., Merkle-Storms, J., Gerfer, S., et al. Evaluation of the GERAADA score for prediction of 30-day mortality in patients with acute type A aortic dissection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021, 59(5), 1109–1114. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, F., Zhou, Q., Pan, J., et al. Clinical outcomes of postoperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in Stanford type a aortic dissection. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021, 21(1), 35, Published 2021 Feb 5. [CrossRef]

- Pérez Vela, J.L., Llanos Jorge, C., Duerto Álvarez, J., Jiménez Rivera, J.J. Clinical management of postcardiotomy shock in adults. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed) 2022, 46(6), 312–325. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).