Submitted:

20 March 2023

Posted:

22 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

2.2. Production of hybridoma cells

2.3. ELISA

2.4. Flow Cytometry

2.5. Determination of Apparent Dissociation Constant (KD) by Flow Cytometry

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

2.7. Immunohistochemical Analysis

3. Results

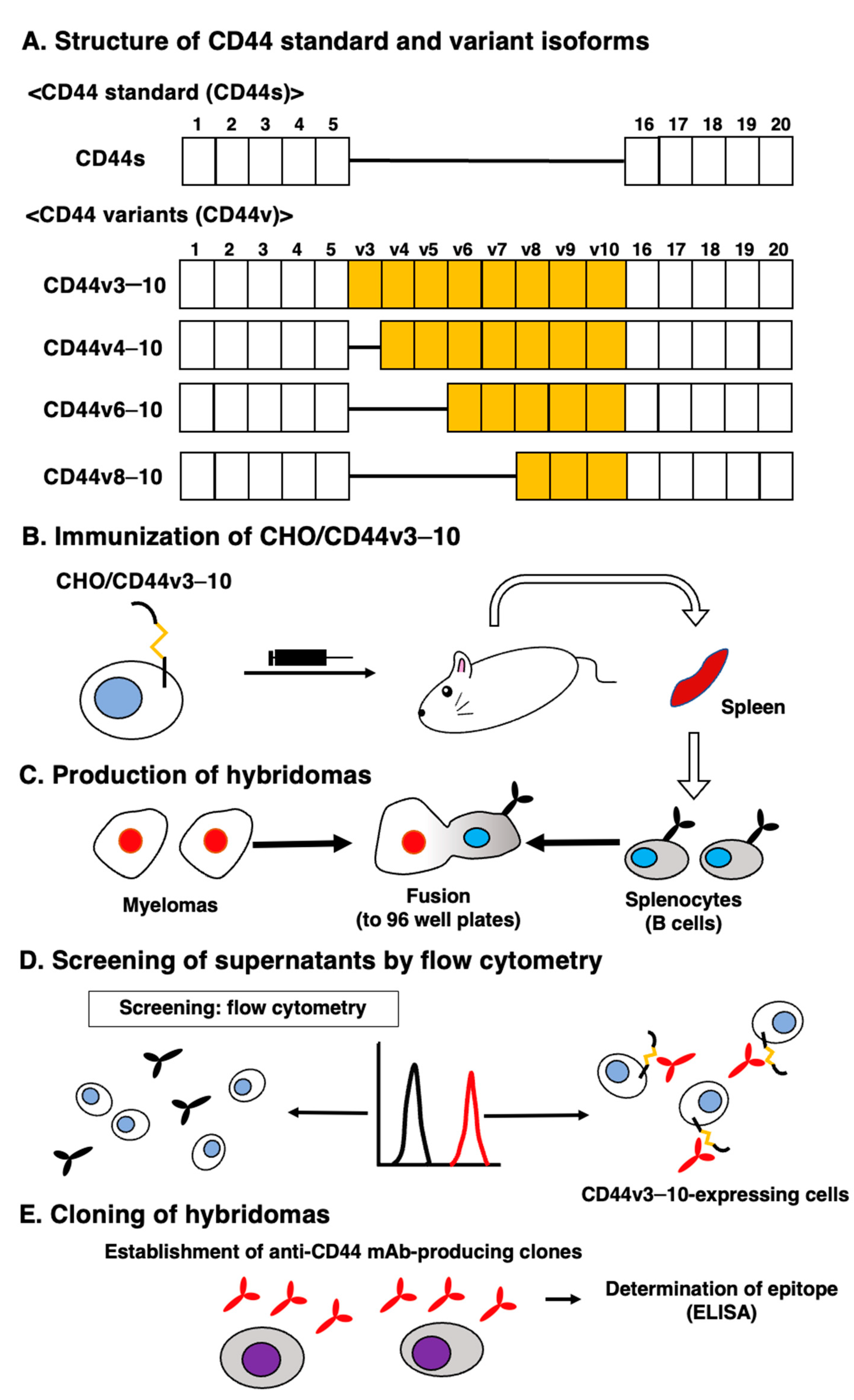

2.1. Establishment of an Anti-CD44v9 mAb, C44Mab-1

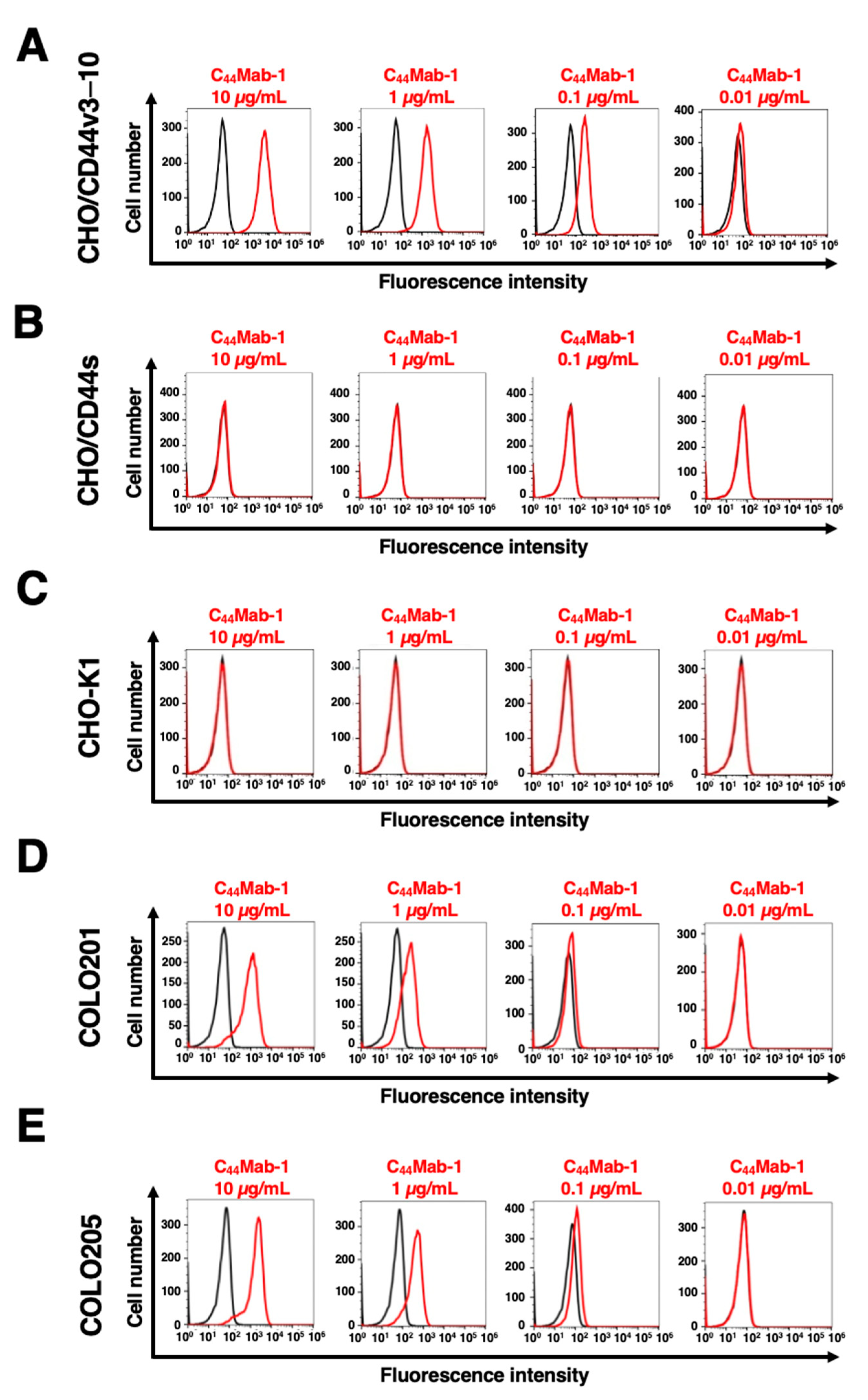

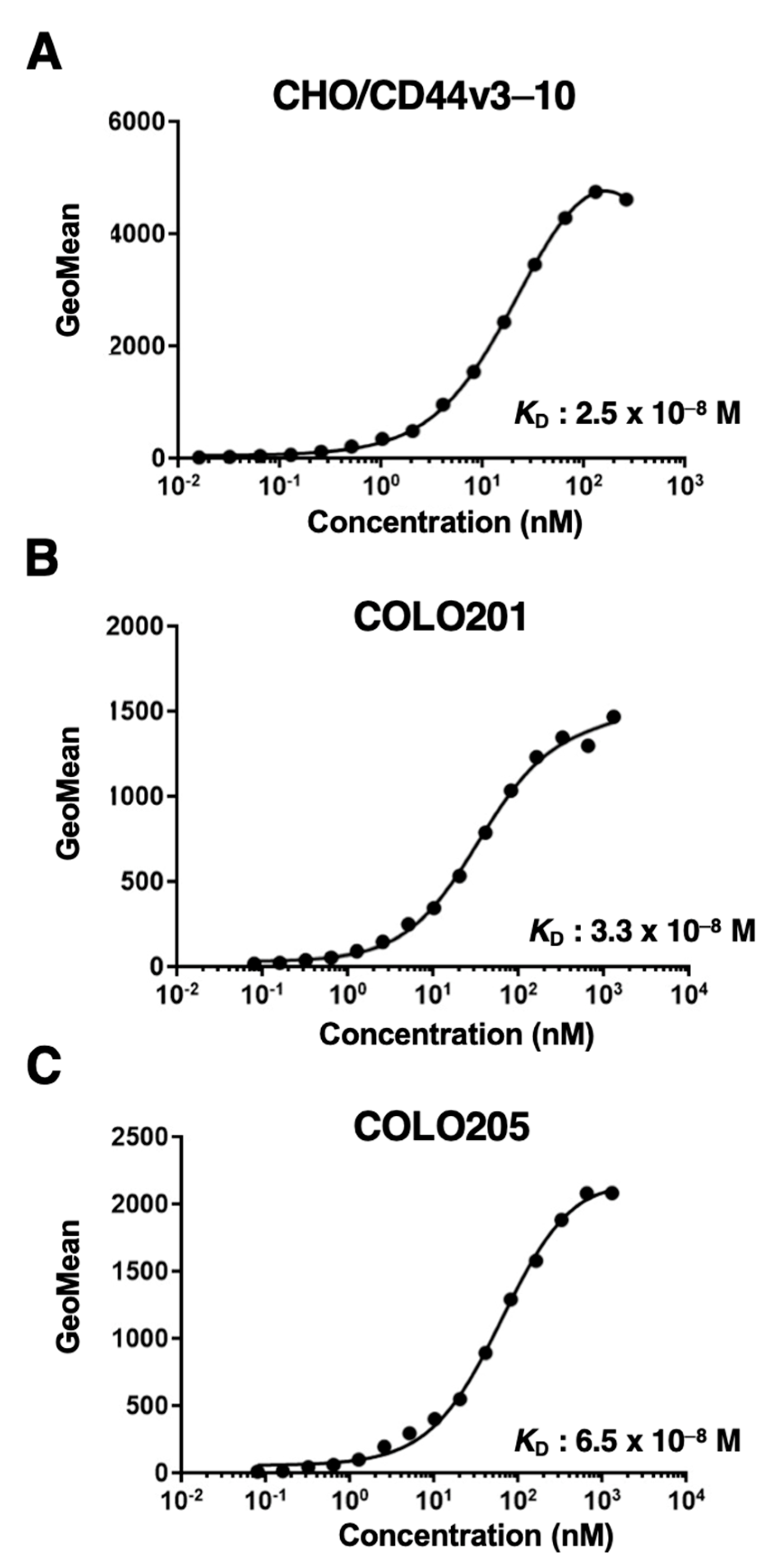

2.2. Flow Cytometric Analysis of C44Mab-1 to CD44-Expressing Cells

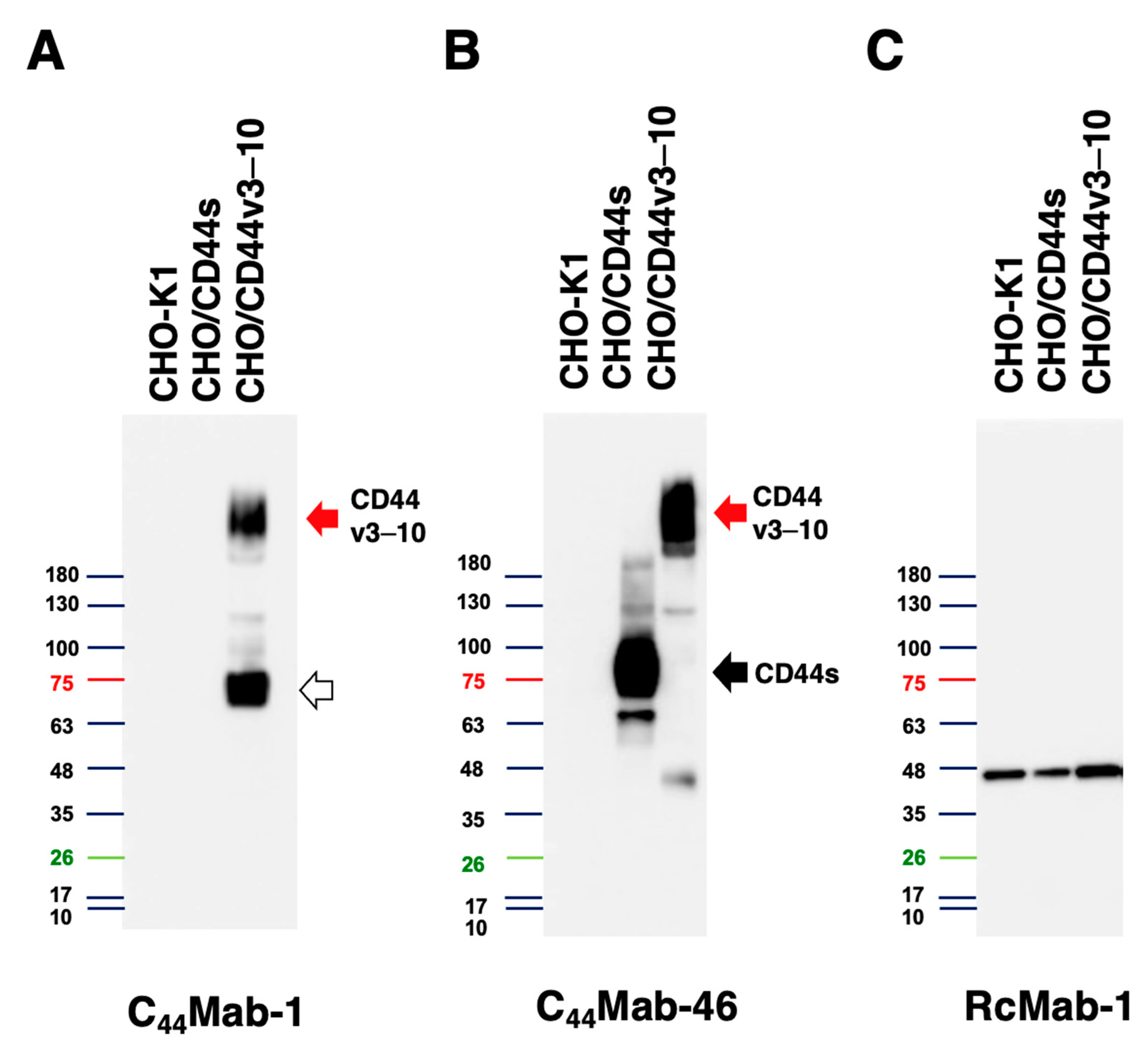

2.3. Western Blot Analysis

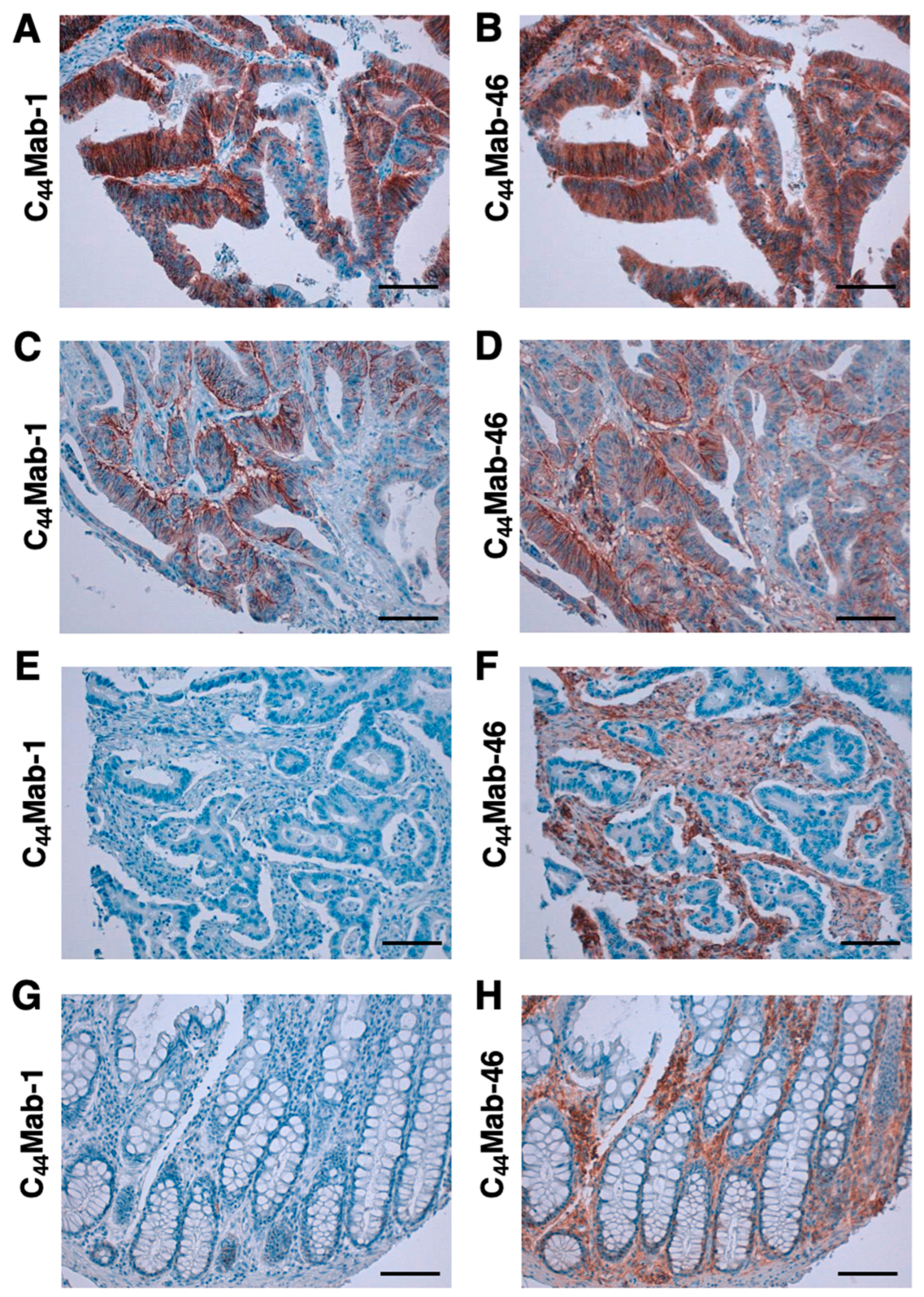

2.4. Immunohistochemical Analysis using C44Mab-1 against Tumor Tissues

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fox, S.B.; Fawcett, J.; Jackson, D.G.; Collins, I.; Gatter, K.C.; Harris, A.L.; Gearing, A.; Simmons, D.L. Normal human tissues, in addition to some tumors, express multiple different CD44 isoforms. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 4539–4546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ponta, H.; Sherman, L.; Herrlich, P.A. CD44: from adhesion molecules to signalling regulators. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Zuo, X.; Wei, D. Concise Review: Emerging Role of CD44 in Cancer Stem Cells: A Promising Biomarker and Therapeutic Target. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015, 4, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, S.; Karnad, A.; Freeman, J.W. The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: therapeutic implications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slevin, M.; Krupinski, J.; Gaffney, J.; Matou, S.; West, D.; Delisser, H.; Savani, R.C.; Kumar, S. Hyaluronan-mediated angiogenesis in vascular disease: uncovering RHAMM and CD44 receptor signaling pathways. Matrix Biol. 2007, 26, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.L.; Li, D.; Lu, T.X.; Chang, S.W. Structural Characterization of the CD44 Stem Region for Standard and Cancer-Associated Isoforms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, M.N.; Chandavarkar, V.; Sharma, R.; Bhargava, D. Structure, function and role of CD44 in neoplasia. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Pathol. 2019, 23, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassn Mesrati, M.; Syafruddin, S.E.; Mohtar, M.A.; Syahir, A. CD44: A Multifunctional Mediator of Cancer Progression. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, N.; Szczepanski, M.J.; Gluszko, A.; Szafarowski, T.; Azambuja, J.H.; Dolg, L.; Gellrich, N.C.; Kampmann, A.; Whiteside, T.L.; Zimmerer, R.M. CD44(+) tumor cells promote early angiogenesis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2019, 467, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durko, L.; Wlodarski, W.; Stasikowska-Kanicka, O.; Wagrowska-Danilewicz, M.; Danilewicz, M.; Hogendorf, P.; Strzelczyk, J.; Malecka-Panas, E. Expression and Clinical Significance of Cancer Stem Cell Markers CD24, CD44, and CD133 in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Chronic Pancreatitis. Dis. Markers 2017, 2017, 3276806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gzil, A.; Zarębska, I.; Bursiewicz, W.; Antosik, P.; Grzanka, D.; Szylberg, Ł. Markers of pancreatic cancer stem cells and their clinical and therapeutic implications. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 6629–6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Taftaf, R.; Kawaguchi, M.; Chang, Y.F.; Chen, W.; Entenberg, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gerratana, L.; Huang, S.; Patel, D.B.; et al. Homophilic CD44 Interactions Mediate Tumor Cell Aggregation and Polyclonal Metastasis in Patient-Derived Breast Cancer Models. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 96–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassn Mesrati, M.; Behrooz, A.B.; A, Y.A.; Syahir, A. Understanding Glioblastoma Biomarkers: Knocking a Mountain with a Hammer. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, K.J.; Shukla, P.; Springer, K.; Lee, S.; Coombes, J.D.; Choy, C.J.; Kenny, S.J.; Xu, K.; Kumar, S. A mode of cell adhesion and migration facilitated by CD44-dependent microtentacles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2020, 117, 11432–11443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Qian, L.; Lin, J.; Huang, G.; Hao, N.; Wei, X.; Wang, W.; Liang, J. CD44 regulates prostate cancer proliferation, invasion and migration via PDK1 and PFKFB4. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 65143–65151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Xie, L.; Huang, A.; Xue, C.; Gu, Z.; Wang, K.; Zong, S. The Prognostic and Clinical Value of CD44 in Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zöller, M. CD44: can a cancer-initiating cell profit from an abundantly expressed molecule? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Yang, C.; Gao, F. The state of CD44 activation in cancer progression and therapeutic targeting. Febs J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morath, I.; Hartmann, T.N.; Orian-Rousseau, V. CD44: More than a mere stem cell marker. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 81, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K.L.; Jackson, D.G.; Simon, J.C.; Tanczos, E.; Peach, R.; Modrell, B.; Stamenkovic, I.; Plowman, G.; Aruffo, A. CD44 isoforms containing exon V3 are responsible for the presentation of heparin-binding growth factor. J. Cell Biol. 1995, 128, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orian-Rousseau, V.; Chen, L.; Sleeman, J.P.; Herrlich, P.; Ponta, H. CD44 is required for two consecutive steps in HGF/c-Met signaling. Genes. Dev. 2002, 16, 3074–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishimoto, T.; Nagano, O.; Yae, T.; Tamada, M.; Motohara, T.; Oshima, H.; Oshima, M.; Ikeda, T.; Asaba, R.; Yagi, H.; et al. CD44 variant regulates redox status in cancer cells by stabilizing the xCT subunit of system xc(-) and thereby promotes tumor growth. Cancer Cell 2011, 19, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagami, T.; Yamade, M.; Suzuki, T.; Uotani, T.; Tani, S.; Hamaya, Y.; Iwaizumi, M.; Osawa, S.; Sugimoto, K.; Baba, S.; et al. High expression level of CD44v8-10 in cancer stem-like cells is associated with poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma patients treated with chemoradiotherapy. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 34876–34888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, S.; Itai, S.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Detection of high CD44 expression in oral cancers using the novel monoclonal antibody, C(44)Mab-5. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2018, 14, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, N.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Asano, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Anti-CD44 Monoclonal Antibody for Multiple Applications against Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takei, J.; Asano, T.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Epitope Mapping of the Anti-CD44 Monoclonal Antibody (C44Mab-46) Using Alanine-Scanning Mutagenesis and Surface Plasmon Resonance. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2021, 40, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Takei, J.; Tateyama, N.; Kato, Y. Epitope Mapping of the Anti-CD44 Monoclonal Antibody (C44Mab-46) Using the REMAP Method. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2021, 40, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asano, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Epitope Mapping System: RIEDL Insertion for Epitope Mapping Method. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2021, 40, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, J.; Kaneko, M.K.; Ohishi, T.; Hosono, H.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Sano, M.; Asano, T.; Sayama, Y.; Kawada, M.; et al. A defucosylated antiCD44 monoclonal antibody 5mG2af exerts antitumor effects in mouse xenograft models of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 44, 1949–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Goto, N.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Anti-CD44 Variant 4 Monoclonal Antibody C44Mab-108 for Immunohistochemistry. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 1875–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejima, R.; Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Asano, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Novel Anti-CD44 Variant 6 Monoclonal Antibody C(44)Mab-9 for Multiple Applications against Colorectal Carcinomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Yamada, S.; Furusawa, Y.; Itai, S.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Sano, M.; Harada, H.; Fukui, M.; Kaneko, M.K. PMab-213: A Monoclonal Antibody for Immunohistochemical Analysis Against Pig Podoplanin. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2019, 38, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furusawa, Y.; Yamada, S.; Itai, S.; Sano, M.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Fukui, M.; Harada, H.; Mizuno, T.; Sakai, Y.; et al. PMab-210: A Monoclonal Antibody Against Pig Podoplanin. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2019, 38, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furusawa, Y.; Yamada, S.; Itai, S.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Sano, M.; Harada, H.; Fukui, M.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. PMab-219: A monoclonal antibody for the immunohistochemical analysis of horse podoplanin. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2019, 18, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furusawa, Y.; Yamada, S.; Itai, S.; Nakamura, T.; Takei, J.; Sano, M.; Harada, H.; Fukui, M.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Establishment of a monoclonal antibody PMab-233 for immunohistochemical analysis against Tasmanian devil podoplanin. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2019, 18, 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kuno, A.; Uchiyama, N.; Amano, K.; Chiba, Y.; Hasegawa, Y.; Hirabayashi, J.; Narimatsu, H.; Mishima, K.; et al. Inhibition of tumor cell-induced platelet aggregation using a novel anti-podoplanin antibody reacting with its platelet-aggregation-stimulating domain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 349, 1301–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalise, L.; Kato, A.; Ohno, M.; Maeda, S.; Yamamichi, A.; Kuramitsu, S.; Shiina, S.; Takahashi, H.; Ozone, S.; Yamaguchi, J.; et al. Efficacy of cancer-specific anti-podoplanin CAR-T cells and oncolytic herpes virus G47Delta combination therapy against glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2022, 26, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, A.; Waseda, M.; Ishii, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Kaneko, S. Improved anti-solid tumor response by humanized anti-podoplanin chimeric antigen receptor transduced human cytotoxic T cells in an animal model. Genes. Cells 2022, 27, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura-Sakaguchi, R.; Aruga, R.; Hirose, M.; Ekimoto, T.; Miyake, T.; Hizukuri, Y.; Oi, R.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Akiyama, Y.; et al. Moving toward generalizable NZ-1 labeling for 3D structure determination with optimized epitope-tag insertion. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2021, 77, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Ohishi, T.; Nakamura, T.; Inoue, H.; Takei, J.; Sano, M.; Asano, T.; Sayama, Y.; Hosono, H.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Development of Core-Fucose-Deficient Humanized and Chimeric Anti-Human Podoplanin Antibodies. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2020, 39, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Matsunaga, Y.; Arimori, T.; Kitago, Y.; Ogasawara, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Takagi, J. Tailored placement of a turn-forming PA tag into the structured domain of a protein to probe its conformational state. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 1512–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; Tsuchihashi, Y.; Izumi, T.; Ogasawara, S.; Okada, N.; Sato, C.; Tobiume, M.; Otsuka, K.; Miyamoto, L.; et al. Antitumor effect of novel anti-podoplanin antibody NZ-12 against malignant pleural mesothelioma in an orthotopic xenograft model. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Abe, S.; Ogasawara, S.; Fujii, Y.; Yamada, S.; Murata, T.; Uchida, H.; Tahara, H.; Nishioka, Y.; Kato, Y. Chimeric Anti-Human Podoplanin Antibody NZ-12 of Lambda Light Chain Exerts Higher Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity and Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity Compared with NZ-8 of Kappa Light Chain. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2017, 36, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, A.; Ohta, M.; Kato, Y.; Inada, S.; Kato, T.; Nakata, S.; Yatabe, Y.; Goto, M.; Kaneda, N.; Kurita, K.; et al. A Real-Time Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging Method for the Detection of Oral Cancers in Mice Using an Indocyanine Green-Labeled Podoplanin Antibody. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 17, 1533033818767936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, R.; Oi, R.; Akashi, S.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Nogi, T. Application of the NZ-1 Fab as a crystallization chaperone for PA tag-inserted target proteins. Protein Sci. 2019, 28, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiina, S.; Ohno, M.; Ohka, F.; Kuramitsu, S.; Yamamichi, A.; Kato, A.; Motomura, K.; Tanahashi, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Watanabe, R.; et al. CAR T Cells Targeting Podoplanin Reduce Orthotopic Glioblastomas in Mouse Brains. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016, 4, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwata, T.; Yoneda, K.; Mori, M.; Kanayama, M.; Kuroda, K.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Tanaka, F. Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma (MPM) with the "Universal" CTC-Chip and An Anti-Podoplanin Antibody NZ-1.2. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishinaga, Y.; Sato, K.; Yasui, H.; Taki, S.; Takahashi, K.; Shimizu, M.; Endo, R.; Koike, C.; Kuramoto, N.; Nakamura, S.; et al. Targeted Phototherapy for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Near-Infrared Photoimmunotherapy Targeting Podoplanin. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Neyazaki, M.; Nogi, T.; Kato, Y.; Takagi, J. PA tag: a versatile protein tagging system using a super high affinity antibody against a dodecapeptide derived from human podoplanin. Protein Expr. Purif. 2014, 95, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kunita, A.; Ito, H.; Kameyama, A.; Ogasawara, S.; Matsuura, N.; Hasegawa, Y.; Suzuki-Inoue, K.; Inoue, O.; et al. Molecular analysis of the pathophysiological binding of the platelet aggregation-inducing factor podoplanin to the C-type lectin-like receptor CLEC-2. Cancer Sci. 2008, 99, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y.; Vaidyanathan, G.; Kaneko, M.K.; Mishima, K.; Srivastava, N.; Chandramohan, V.; Pegram, C.; Keir, S.T.; Kuan, C.T.; Bigner, D.D.; et al. Evaluation of anti-podoplanin rat monoclonal antibody NZ-1 for targeting malignant gliomas. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2010, 37, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y. Specific monoclonal antibodies against IDH1/2 mutations as diagnostic tools for gliomas. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2015, 32, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikota, H.; Nobusawa, S.; Arai, H.; Kato, Y.; Ishizawa, K.; Hirose, T.; Yokoo, H. Evaluation of IDH1 status in diffusely infiltrating gliomas by immunohistochemistry using anti-mutant and wild type IDH1 antibodies. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2015, 32, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itai, S.; Ohishi, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Yamada, S.; Abe, S.; Nakamura, T.; Yanaka, M.; Chang, Y.W.; Ohba, S.I.; Nishioka, Y.; et al. Anti-podocalyxin antibody exerts antitumor effects via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in mouse xenograft models of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 22480–22497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Imaeda, H.; Matsuzaki, J.; Tsugawa, H.; Nagano, O.; Asakura, K.; Saya, H.; Hibi, T. CD44 variant 9 expression in primary early gastric cancer as a predictive marker for recurrence. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiwara, M.; Kikuchi, E.; Kosaka, T.; Mikami, S.; Saya, H.; Oya, M. Variant isoforms of CD44 expression in upper tract urothelial cancer as a predictive marker for recurrence and mortality. Urol. Oncol. 2016, 34, 337.e319–e326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakehashi, A.; Ishii, N.; Sugihara, E.; Gi, M.; Saya, H.; Wanibuchi, H. CD44 variant 9 is a potential biomarker of tumor initiating cells predicting survival outcome in hepatitis C virus-positive patients with resected hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagiwara, M.; Kikuchi, E.; Tanaka, N.; Kosaka, T.; Mikami, S.; Saya, H.; Oya, M. Variant isoforms of CD44 involves acquisition of chemoresistance to cisplatin and has potential as a novel indicator for identifying a cisplatin-resistant population in urothelial cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seishima, R.; Okabayashi, K.; Nagano, O.; Hasegawa, H.; Tsuruta, M.; Shimoda, M.; Kameyama, K.; Saya, H.; Kitagawa, Y. Sulfasalazine, a therapeutic agent for ulcerative colitis, inhibits the growth of CD44v9(+) cancer stem cells in ulcerative colitis-related cancer. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2016, 40, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, S.; Tsugawa, H.; Matsuzaki, J.; Hirata, K.; Mori, H.; Saya, H.; Kanai, T.; Suzuki, H. Inhibiting xCT Improves 5-Fluorouracil Resistance of Gastric Cancer Induced by CD44 Variant 9 Expression. Anticancer. Res. 2018, 38, 6163–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Kato, C.; Mori, H.; Matsuzaki, J.; Kameyama, K.; Saya, H.; Hatakeyama, M.; Suematsu, M.; Suzuki, H. Cancer Stem-Cell Marker CD44v9-Positive Cells Arise From Helicobacter pylori-Infected CAPZA1-Overexpressing Cells. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 8, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanee, M.; Padthaisong, S.; Suksawat, M.; Dokduang, H.; Phetcharaburanin, J.; Klanrit, P.; Titapun, A.; Namwat, N.; Wangwiwatsin, A.; Sa-Ngiamwibool, P.; et al. Sulfasalazine modifies metabolic profiles and enhances cisplatin chemosensitivity on cholangiocarcinoma cells in in vitro and in vivo models. Cancer Metab. 2021, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shitara, K.; Doi, T.; Nagano, O.; Imamura, C.K.; Ozeki, T.; Ishii, Y.; Tsuchihashi, K.; Takahashi, S.; Nakajima, T.E.; Hironaka, S.; et al. Dose-escalation study for the targeting of CD44v(+) cancer stem cells by sulfasalazine in patients with advanced gastric cancer (EPOC1205). Gastric Cancer 2017, 20, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mereiter, S.; Martins Á, M.; Gomes, C.; Balmaña, M.; Macedo, J.A.; Polom, K.; Roviello, F.; Magalhães, A.; Reis, C.A. O-glycan truncation enhances cancer-related functions of CD44 in gastric cancer. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 1675–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guinney, J.; Dienstmann, R.; Wang, X.; de Reyniès, A.; Schlicker, A.; Soneson, C.; Marisa, L.; Roepman, P.; Nyamundanda, G.; Angelino, P.; et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wielenga, V.J.; Smits, R.; Korinek, V.; Smit, L.; Kielman, M.; Fodde, R.; Clevers, H.; Pals, S.T. Expression of CD44 in Apc and Tcf mutant mice implies regulation by the WNT pathway. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 154, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, S.J.; Tarone, G.; Underhill, C.B. Distribution of hyaluronate and hyaluronate receptors in the adult lung. J. Cell Sci. 1988, 90 ( Pt. 1), 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, S.; Koch, M.; Nübel, T.; Ladwein, M.; Antolovic, D.; Klingbeil, P.; Hildebrand, D.; Moldenhauer, G.; Langbein, L.; Franke, W.W.; et al. A complex of EpCAM, claudin-7, CD44 variant isoforms, and tetraspanins promotes colorectal cancer progression. Mol. Cancer Res. 2007, 5, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliferenko, S.; Paiha, K.; Harder, T.; Gerke, V.; Schwärzler, C.; Schwarz, H.; Beug, H.; Günthert, U.; Huber, L.A. Analysis of CD44-containing lipid rafts: Recruitment of annexin II and stabilization by the actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 146, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orian-Rousseau, V.; Ponta, H. Perspectives of CD44 targeting therapies. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke-van der Houven van Oordt, C.W.; Gomez-Roca, C.; van Herpen, C.; Coveler, A.L.; Mahalingam, D.; Verheul, H.M.; van der Graaf, W.T.; Christen, R.; Rüttinger, D.; Weigand, S.; et al. First-in-human phase I clinical trial of RG7356, an anti-CD44 humanized antibody, in patients with advanced, CD44-expressing solid tumors. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 80046–80058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riechelmann, H.; Sauter, A.; Golze, W.; Hanft, G.; Schroen, C.; Hoermann, K.; Erhardt, T.; Gronau, S. Phase I trial with the CD44v6-targeting immunoconjugate bivatuzumab mertansine in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral. Oncol. 2008, 44, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tijink, B.M.; Buter, J.; de Bree, R.; Giaccone, G.; Lang, M.S.; Staab, A.; Leemans, C.R.; van Dongen, G.A. A phase I dose escalation study with anti-CD44v6 bivatuzumab mertansine in patients with incurable squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck or esophagus. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 6064–6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casucci, M.; Nicolis di Robilant, B.; Falcone, L.; Camisa, B.; Norelli, M.; Genovese, P.; Gentner, B.; Gullotta, F.; Ponzoni, M.; Bernardi, M.; et al. CD44v6-targeted T cells mediate potent antitumor effects against acute myeloid leukemia and multiple myeloma. Blood 2013, 122, 3461–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porcellini, S.; Asperti, C.; Corna, S.; Cicoria, E.; Valtolina, V.; Stornaiuolo, A.; Valentinis, B.; Bordignon, C.; Traversari, C. CAR T Cells Redirected to CD44v6 Control Tumor Growth in Lung and Ovary Adenocarcinoma Bearing Mice. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K. A cancer-specific monoclonal antibody recognizes the aberrantly glycosylated podoplanin. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Nakamura, T.; Kunita, A.; Fukayama, M.; Abe, S.; Nishioka, Y.; Yamada, S.; Yanaka, M.; Saidoh, N.; Yoshida, K.; et al. ChLpMab-23: Cancer-Specific Human-Mouse Chimeric Anti-Podoplanin Antibody Exhibits Antitumor Activity via Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity. Monoclon. Antib. Immunodiagn. Immunother. 2017, 36, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Yamada, S.; Nakamura, T.; Abe, S.; Nishioka, Y.; Kunita, A.; Fukayama, M.; Fujii, Y.; Ogasawara, S.; Kato, Y. Antitumor activity of chLpMab-2, a human-mouse chimeric cancer-specific antihuman podoplanin antibody, via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Roles of Podoplanin in Malignant Progression of Tumor. Cells 2022, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Ohishi, T.; Kawada, M.; Kato, Y. A cancer-specific anti-podocalyxin monoclonal antibody (60-mG(2a)-f) exerts antitumor effects in mouse xenograft models of pancreatic carcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2020, 24, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, A.; Waseda, M.; Ishii, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Kaneko, S. Improved anti-solid tumor response by humanized anti-podoplanin chimeric antigen receptor transduced human cytotoxic T cells in an animal model. Genes. Cells 2022, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalise, L.; Kato, A.; Ohno, M.; Maeda, S.; Yamamichi, A.; Kuramitsu, S.; Shiina, S.; Takahashi, H.; Ozone, S.; Yamaguchi, J.; et al. Efficacy of cancer-specific anti-podoplanin CAR-T cells and oncolytic herpes virus G47Δ combination therapy against glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. - Oncolytics 2022, 26, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Roles of Podoplanin in Malignant Progression of Tumor. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Age | Sex | Organ | Pathology diagnosis | Grade | Stage | Type | C44Mab-1 | C44Mab-46 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 1 | - | Malignant | + | + |

| 2 | 48 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 1 | IIA | Malignant | - | - |

| 3 | 58 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 1--2 | IIA | Malignant | + | + |

| 4 | 75 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 1 | IV | Malignant | - | ++ |

| 5 | 86 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | II | Malignant | - | + |

| 6 | 55 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIC | Malignant | - | - |

| 7 | 38 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 1 | I | Malignant | - | ++ |

| 8 | 52 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 1 | IIIB | Malignant | + | - |

| 9 | 46 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | Malignant | ++ | + |

| 10 | 61 | M | Colon | Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | Malignant | + | ++ |

| 11 | 55 | M | Colon | Mucinous adenocarcinoma with necrosis | 2 | IIA | Malignant | - | ++ |

| 12 | 55 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 1 | IIIB | Malignant | + | - |

| 13 | 44 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 1 | - | Malignant | - | - |

| 14 | 31 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | Malignant | - | + |

| 15 | 74 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | Malignant | + | + |

| 16 | 61 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | II | Malignant | ++ | ++ |

| 17 | 45 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | III | Malignant | + | + |

| 18 | 58 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | Malignant | - | ++ |

| 19 | 58 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIA | Malignant | +++ | +++ |

| 20 | 69 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 3 | - | Malignant | - | - |

| 21 | 64 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIC | Malignant | ++ | ++ |

| 22 | 82 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | Malignant | - | - |

| 23 | 34 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | Malignant | ++ | ++ |

| 24 | 50 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIB | Malignant | - | - |

| 25 | 34 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 1 | IIB | Malignant | - | + |

| 26 | 52 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIA | Malignant | - | + |

| 27 | 53 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | Malignant | - | - |

| 28 | 58 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | I | Malignant | - | + |

| 29 | 59 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIA | Malignant | ++ | ++ |

| 30 | 67 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | Malignant | - | ++ |

| 31 | 31 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | Malignant | +++ | +++ |

| 32 | 54 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIB | Malignant | - | + |

| 33 | 54 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | Malignant | - | - |

| 34 | 62 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | - | Malignant | - | + |

| 35 | 67 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | - | Malignant | + | - |

| 36 | 52 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIA | Malignant | - | - |

| 37 | 52 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 3 | IIIB | Malignant | - | - |

| 38 | 75 | M | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | - | Malignant | - | - |

| 39 | 57 | F | Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIB | Malignant | + | +++ |

| 40 | 38 | M | Colon | Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 3 | I | Malignant | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).