Introduction

Out-of-pocket costs can be defined as the direct payments made by an individual to healthcare providers at the time of provision of a service.1,2 Naturally, there are other, indirect costs connected to the provision of such services, for instance, the cost of transportation and food, the loss of earnings caused by medical visits, and especially the loss of time, which is particularly important when the service must be provided outside of the locality where the patients live. Indirect costs are decisive in terms of access to healthcare, as they can be higher for some households and, in some cases, may lead to lack of adherence to treatment.3 Many specialists believe that a broader concept of out-of-pocket costs is more useful, as it better reflects what happens in practice.4,5

When out-of-pocket costs are required for the provision of healthcare, they become an access barrier. Even when minimal, they just need to be high enough in relation to the paying capacity of a household to be relevant. They are, therefore, a determinant factor in the management of chronic diseases, as they contribute to the impoverishment of people and the unequal provision of healthcare. Out-of-pocket costs may negatively affect the level of wellbeing of the households concerned and their consumption of other basic goods and services, such as food, rent, or educational fees.6

In Colombia, health expenditures are primarily covered by public funds. According to data from 2019, this amounts to 1,276 USD per capita,7 989 USD (or 77%) of which are absorbed by government entities. Out-of-pocket costs, amounting to 190 USD per capita and equivalent to 20.6% of health expenditure, are among the lowest in the region.8

Research conducted with Chagas patients in Colombia in 2017 has shown that the amount of direct non-medical costs reached 1.5 million USD, corresponding to 20.4% of the total direct costs related to the disease in that year.9 It has been noted that more than half of the total out-of-pocket costs were related to food, transportation, and accommodation during the treatment. It is estimated that society pays 4,226 USD a year for the treatment of each patient with chronic T. cruzi infection/Chagas disease.6

In 2016, Colombia published resolution 3202 concerning the adoption of a manual on the development and implementation of Comprehensive Healthcare Roadmaps for the management of different diseases (Rutas Integrales de Atención en Salud, RIAS). Consequently, a number of RIAS were created, including one for Chagas, to use as tools within the Comprehensive Healthcare Model (Modelo Integral de Salud, MIAS) and to ensure the population can enjoy the right to health. With their focus on the patient, the RIAS mitigate the costs inherent in a fragmented healthcare model, as well as having other positive aspects.10

It is necessary to identify and analyze the costs that patients incur during a long treatment if we want to ensure that they adhere to the treatment and, consequently, experience fewer complications. Mitigation of these complications would lead to a favorable economic impact not only for the patient but also for society as whole, decreasing the burden of the disease in terms of both individual and public health. Moreover, alternative mechanisms that can tackle such costs are urgently needed, so that appropriate health polices can be developed to improve access to essential healthcare services and, ultimately, so that the vicious cycle of poverty and disease can be broken.

This analysis is a key element in the development of public policies that can mitigate the payment of out-of-pocket costs by patients with T. cruzi infection/ Chagas disease, facilitating the diagnosis, etiological treatment, and provision of comprehensive care that are part of the goal of eliminating Chagas disease as a public health problem in Colombia.

The goal of this study is to understand from the patients’ perspective the costs they incur in gaining access to diagnosis and etiological treatment of T. cruzi infection/Chagas disease.

Material and Methods

Type of Study

This is a descriptive transversal study based on data from a survey completed by 91 patients with Chagas disease who received care between 2019 and 2020.

Data analysis was organized in three categories: 1. the socioeconomic profiling of the patients; 2. the costs of and time spent on transportation; and 3. money cost was not earned during the whole diagnosis and treatment process.

The results of the analysis of the variables were presented as the mean and its standard deviation for the quantitative variables and as percentages for the qualitative variables. Depending on the type of variables, the differences between the groups were evaluated using the t-test and chi-squared test.

Population and Sample

Ninety-one people with a confirmed diagnosis of T. cruzi infection and living in the municipalities of Mogotes and Soatá, located in the departments of Santander and Boyacá, respectively, were selected for this study. These two municipalities were part of the Chagas Care Pathway implementation project, which had the goal of reducing access barriers to the diagnostic and treatment of the Trypanosoma cruzi infection. During the interviews, two healthcare scenarios were considered for patients with T. cruzi infection/ Chagas disease: the first was treatment at the local primary healthcare hospital, defined as a healthcare center located in the area (municipality) where the interviewee lived and which they visited; the second was treatment at a specialized reference hospital, defined as a specialized healthcare center (internal medicine, cardiology, almost others.) to which the interviewee was referred, and which was located outside of the area where they lived.

Ethical Considerations

Both the study and the tools used for analysis were reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Medical School of the University of Los Andes (protocol number 201909243).

The survey was conducted in person and all participants signed an informed consent form before taking part.

The data was manually collected for each interview and later tabulated and analyzed in Excel.

Results

Social and economic profile of the patients

A total of 91 patients with

T. cruzi infection completed the survey. The majority of the patients surveyed were women (64.8%). 50% of the patients were less than 59 years old. The mean age was 55.5 ±14.1 years and ages ranged from 19 to 80 years. 56% of the patients lived in rural zones (

Table 1).

3/91 (3%) of the population interviewed had attended a technical/trade or professional school. The majority of the patients (58/91; 64%) only had an elementary education. There is no statistically significant difference in the educational levels of women and men. It is noteworthy that 49/91 (54%) of the respondents did not work in a formal capacity and, therefore, had no income. 36/58 (62%) of the women reported that they did not work (

Table 2).

Among patients interviewed, 45/91 (49%) did not report suffering from a clinical condition other than T. cruzi infection. Of those who had comorbidity, 17/91 (19%) said they had two or more pathologies. The most frequently reported comorbidity was high blood pressure (27%).

All respondents were affiliated to the health system, 83/91 (91%) of whom were in the subsidized regimen.

More than half of the respondents 47/91 (52%) looked after their home, and all of these were women. In second place came agriculture, a predominately male occupation, with only three women having this occupation.

50/91 (55%) of the patients did not have a daily income: 55% of the men compared to 65.4% of the women. The average daily income for the women was 2,772 ±5,175 Colombian pesos (COP), while for the men it was 14,091 ±28,727 COP (p=0.006).

The highest reported incomes (from 50,000 to 100,000 COP) were reported by men 3/29 (10.4%). 8/29 (27.6%) of the men had a daily income of >15,000 COP, compared to 3/52 (5.8%) of the women.

Place, time, and costs related to healthcare

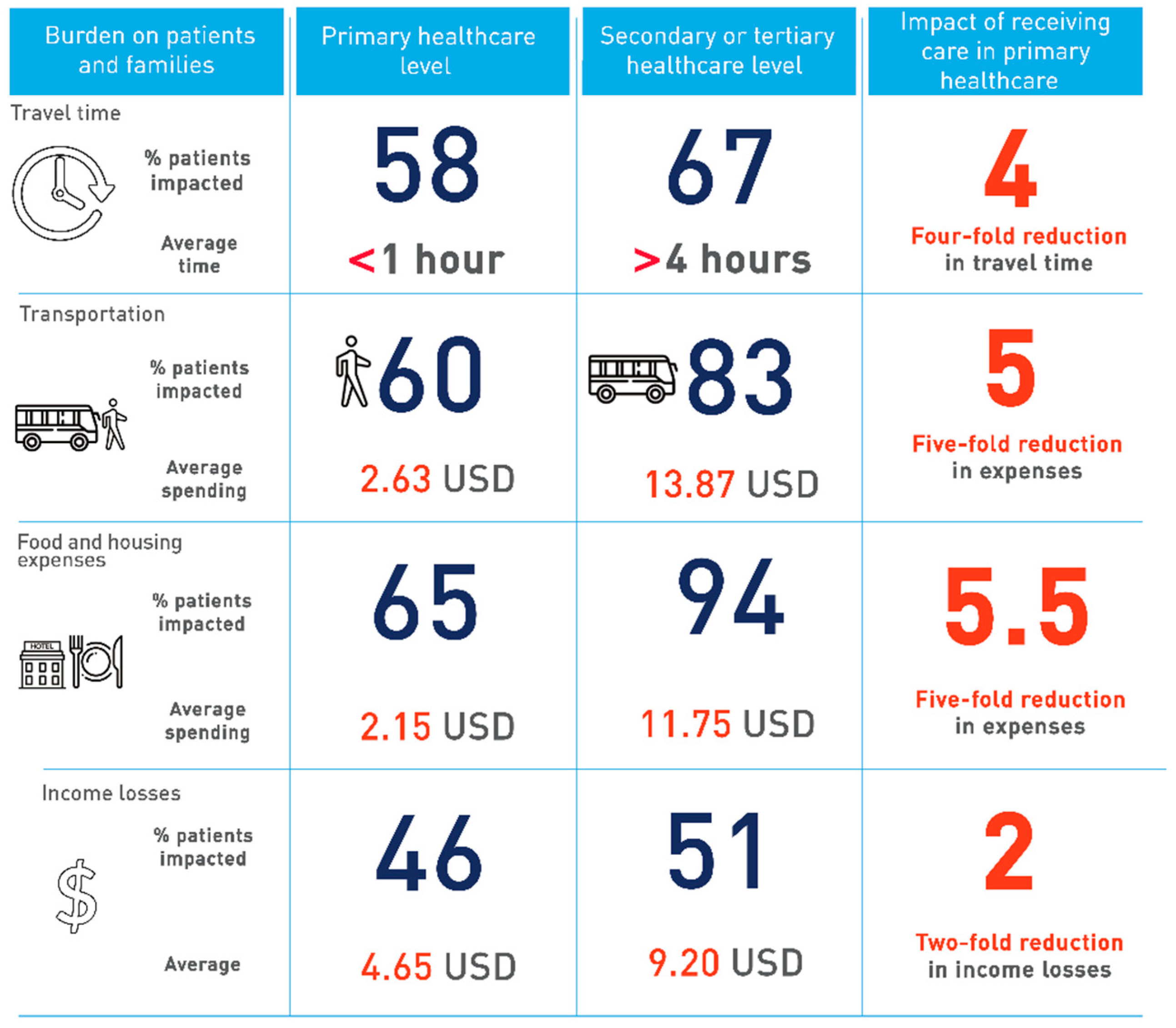

Analysis of the time and costs related to transportation showed a dependence on the level of care at which the patient was seen. Of the 91 patients who participated, 64 (70%) said they were sent to a specialized reference hospital.

53/91 (58%) of the patients spent less than one hour traveling to the local primary care hospital while 30/91 (33%) said they did not spend money on travel. In contrast, the need for transport to the specialized reference hospital impacted patients, as 40/64 (62.5%) of them spent more than 40,000 COP.

36/64 patients (56.2%) that were referred to the specialized reference hospital spent more than 40,000 COP on other costs , such as accommodation, transportation and food. In comparison, 32/91 (35%) of the patients attending a local primary care hospital did not need to pay for accommodation or food and, of those who did, 54/91 (59.3%) spent less than 40,000 COP.

The average cost of transportation to the local primary care hospital was 12,986±17,817 COP, compared to an average cost of 68,4753 ±55,239 COP (p<0.001) for transportation to the high-complexity reference hospital. The average cost for accommodation and food for the local primary care hospital was 10,626 ±12,343 COP, while the average for the reference hospital was 57,991 ±58,338 COP (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Differences in out-of-pocket expenses between the two healthcare scenarios.

Table 3.

Differences in out-of-pocket expenses between the two healthcare scenarios.

| VARIABLEa |

Local primary care hospital (%)(n=91) |

Specialized reference hospital (%)(n=64) |

P valueb

|

|

TRAVEL TIME TO THE CARECENTER

|

|

<0.001 |

| < 1hr |

53 (58.2) |

5 (7.8) |

|

| 1-2 hrs |

21 (23.1) |

5 (7.8) |

|

| 2-4 hrs |

7 (7.7) |

11 (17.2) |

|

| > 4 hrs |

10 (11) |

43 (67.2) |

|

| |

|

|

| TYPE OF TRANSPORT USEDc |

|

<0.001 |

| Walking |

54 (60) |

1 (1.6) |

|

| Motorcycle |

15 (16.7) |

0 |

|

| Car |

12 (13.3) |

10 (15.6) |

|

| Bus |

3 (3.3) |

53 (82.8) |

|

| Other |

6 (6.7) |

0 |

|

| |

|

|

| TRANSPORTATION COSTS (COP) |

|

<0.001 |

| None |

30 (33) |

0 |

|

| <10,000 |

13 (14.3) |

8 (12.5) |

|

| 10,000 – 39,999 |

25 (27.5) |

16 (25) |

|

| 40,000 – 69,999 |

5 (5.5) |

14 (21.9) |

|

| 70,000 – 99,999 |

0 |

7 (10.9) |

|

| >100,000 |

1 (1) |

19 (29.7) |

|

| No data |

17 (18.7) |

0 |

|

| |

|

|

|

OTHER COSTS (food andaccommodation)

|

|

<0.001 |

| None |

32 (35.1) |

1 (1.6) |

|

| <10,000 |

14 (15.4) |

2 (3.1) |

|

| 10,000 – 39,999 |

40 (44) |

22 (34.4) |

|

| 40,000 – 69,999 |

5 (5.5) |

21 (32.8) |

|

| 70,000 – 99,999 |

0 |

3 (4.7) |

|

| 100,000 – 199,999 |

0 |

9 (14) |

|

| >200,000 |

0 |

3 (4.7) |

|

| No data |

0 |

3 (4.7) |

|

| |

|

|

|

OTHER COSTS (material used forpaperwork)

|

|

|

| Patients that paid |

83 (91.21) |

|

| Average cost |

2,961 COP |

|

| |

|

|

| MEDICAL COSTS |

|

|

|

PAID FOR TESTS/EXAMS(ECG, ECO, LAB, etc.) d

|

|

|

| Patients that paid |

7 (7.7) |

5 (7.8) |

|

| Average cost |

167,666 COP* |

415,400 COP |

0.307 |

|

PAYMENT FOR TRYPANOCIDETREATMENT (benznidazole or nifurtimox)

|

|

|

| Patients that paid |

2 (2.2) |

|

| Average cost |

86,500 COP |

|

| |

|

|

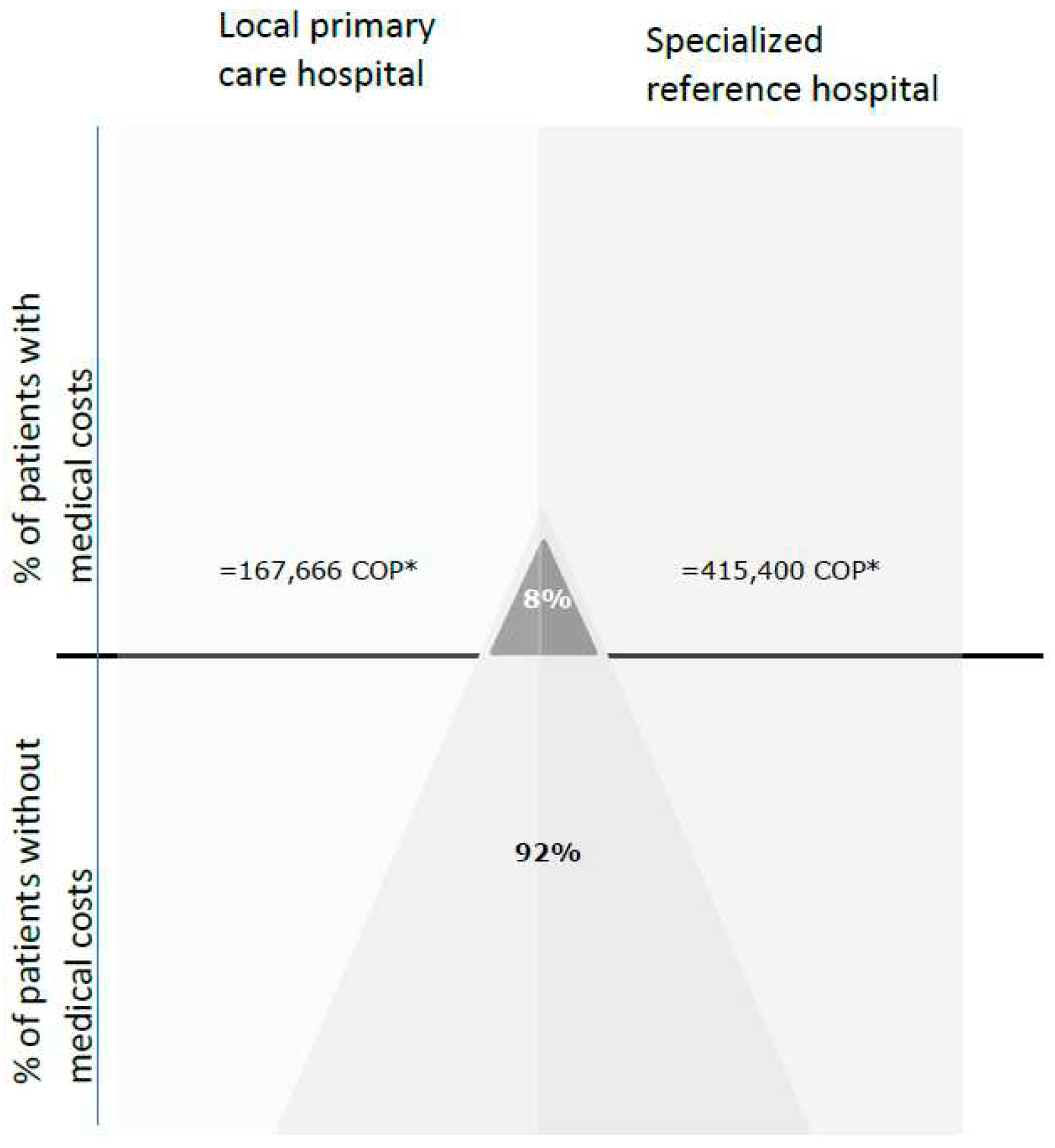

Almost 8% (7/91) of the patients paid for exams such as electrocardiograms, lab tests, and echocardiograms during their period in the healthcare system, both at local primary healthcare facilities and at specialized reference hospitals. Two patients reported that they paid for their antiparasitic medication, which averaged 86,500 COP. This points to the broad coverage of the benefits plan included in the Chagas RIAS.

Chart 1.

Medical costs per healthcare level.* The values correspond to average of medical cost (paid per test/exams) per healthcare level.

Chart 1.

Medical costs per healthcare level.* The values correspond to average of medical cost (paid per test/exams) per healthcare level.

70/91 (76.9%) of the respondents had lab tests carried out at the local primary care hospital, 14/91 (15.4%) had them done outside of their municipality, and the remaining 7/91 (7.7%) somewhere else in their community (a park, school, or other), which probably coincided with collective actions promoted by the program for vector-borne diseases. 62/91 (68%) of the electrocardiograms were done at the local primary care hospital and 84/91 (92.3%) of the respondents did not have to pay for them.

Opportunity costs (money that was not earned)

Of the total number of patients, 42/91 (46.1%) said they lost income every time they had to go to a doctor’s appointment at the local primary care hospital. The percentage increased to 33/64 (51.6%) when the doctor’s appointment was at the specialized reference hospital. Although these percentages were close, the range of lost income for each level of healthcare was very different.

Income lost in both healthcare scenarios was concentrated around the 10,000 COP - 39,999 COP range. In general, the proportion of people in each monetary range was the same in both scenarios. (

Table 4)

However, the average lost income recorded for the local primary care hospital and the specialized reference hospital was 22,982 ±21,395 COP and 45,400 ±41,308 COP, respectively. Those who visited the reference hospital lost more income (p=0.008).

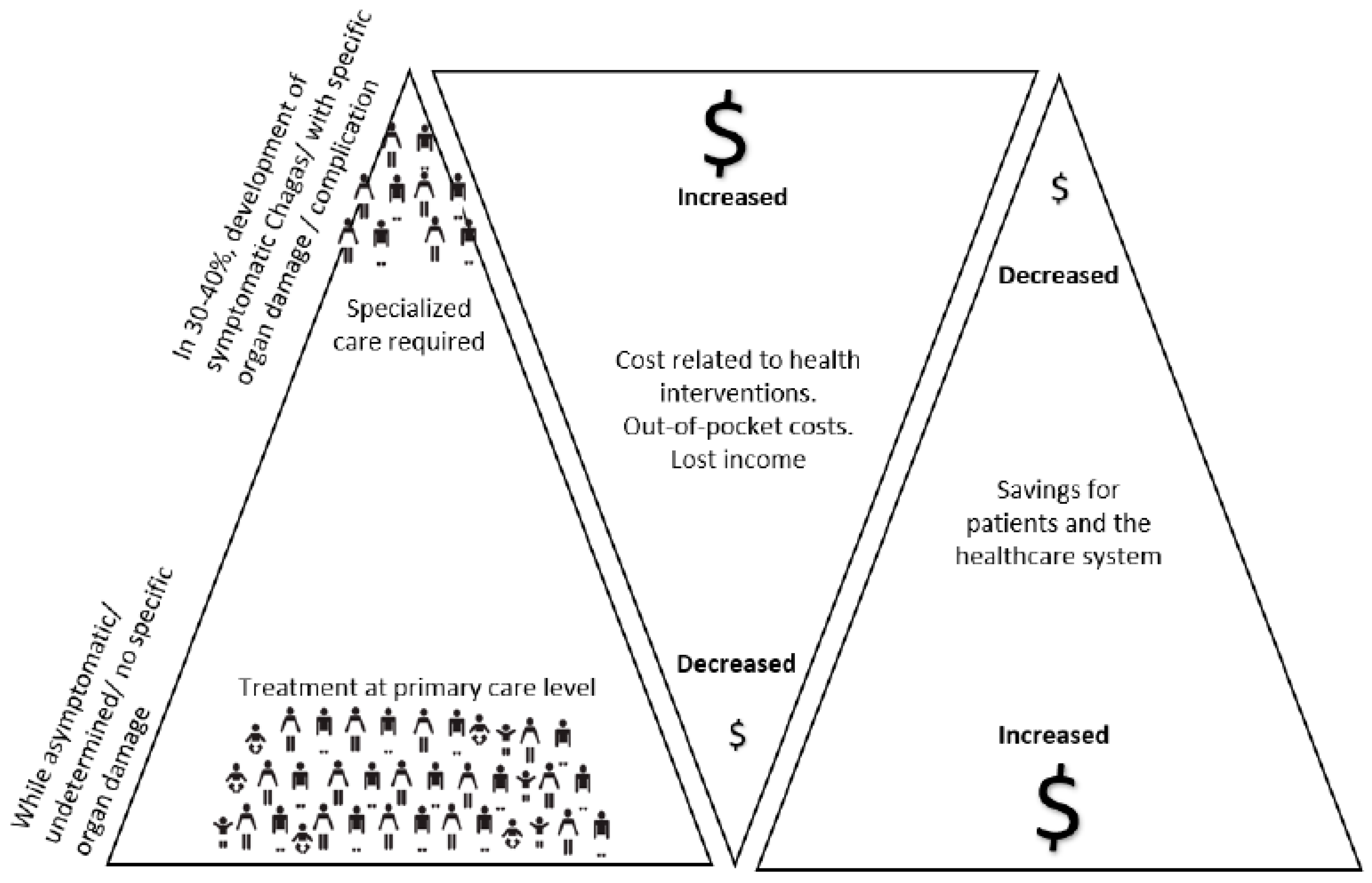

Finally, it is important to consider the relationship between the scenario and focus of healthcare, out-of-pocket costs, and the costs and savings associated with the health system. For

T. cruzi infection/Chagas disease, detecting cases early and promptly means that most cases will not have complications and can be treated at the local levels of healthcare. Consequently, local care, close to the patients’ place of residence, leads to lower or no out-of-pocket costs. From the perspective of the health system, the interventions needed for such patients would be much cheaper than those needed for chronic cases, such as heart transplants, cardiac devices, or lifelong medications, all of which are the product of a health care system focused on complications that privileges specialized care in high-complexity health centers where the patients lose income and spend more on out-of-pocket costs (

Chart 2).

Discussion

The indirect costs, such as those resulting from lost work and lost potential income,11 are important indicators that should be considered and analyzed in connection with out-of-pocket costs incurred in the management of Chagas disease. However, as some critics argue 4 5, very few of these “hidden costs” are recorded in the analysis of direct out-of-pocket costs of healthcare, and few studies have included additional “informal” costs that healthcare users may incur at the point of care. Given the weight of out-of-pocket costs in healthcare, we felt it was necessary to investigate their effect on households and individuals and propose some solutions.

Comparing the findings of our study to the data available in the literature, we found very similar demographic factors in terms of age and gender distribution, which shows that female participants predominate in this type of survey. This suggests that future studies should incorporate a broader analysis to help identify healthcare practices that are effective for both sexes, in addition to other factors that should be considered when proposing changes to healthcare practices, both at the level of the people at risk and at the level of the healthcare system. Our study found that women earn 80% less than men, which may be related to the fact that the majority of women are housewives who, although they have a big impact in terms of social dynamics (a high percentage of them (55%) are head of the household), do not receive a wage for their work.

The majority of the respondents were part of the subsidized regimen, a finding consistent with other studies in Colombia12 that highlights which sector of the population is affected by Chagas disease. This could be decisive in terms of the impact that out-of-pocket costs have on these populations and their role in perpetuating poverty.

In contrast to other previously published studies, we did not find that patients had to pay considerable costs for their medication and medical exams (direct out-of-pocket medical costs), something that may be explained by the improvement in healthcare processes and the gradual expansion of the health benefits plan, as a consequence of the implementation of the law on the fundamental right to health.13 In the case of Chagas disease, implementation of the Comprehensive Healthcare Pathways as a tool for healthcare organization has had a positive impact on patients’ out-of-pocket costs, as exemplified by the fact that blood samples are sent out and that patients no longer need to travel to obtain a diagnosis.

In this study, we found that there was a meaningful difference for patients in terms of non-medical direct costs, such as transportation, accommodation, food, and lost income, when care was provided closer to the patient and by a health service provider located in the area where the patient lives, compared to the costs incurred when specialized care required traveling to another municipality or city. In this latter case, the costs were significantly higher, not only in terms of direct costs but also in terms of lost income. This difference has also been clearly demonstrated in other studies evaluating the determinant factors for out-of-pocket healthcare costs.14 The average costs of transportation, accommodation and food that come with traveling to another city can be higher than the legal daily minimum wage approved in Colombia for 2021.

The efforts made in connection with national and supranational initiatives to improve coverage and access to healthcare, especially in the context of the Agenda for Sustainable Development 2030, have focused on the creation of alternative approaches to economic and social protections in the context of healthcare.15 Healthcare systems must, therefore, consider caring for patients closer to where they live as a way to ensure healthcare access and quality. Moreover, this aligns with the (63rd) 2010 World Health Assembly’s resolution urging all member states to integrate care for patients with both acute clinical and chronic forms of Chagas disease into their primary healthcare services.16

At the national level, it is essential that those who are responsible for health insurance create networks for the provision of healthcare services that ensure the fundamental right to health and uphold the principles of availability, continuity, accessibility and opportunity, among others. Specialized care days at rural areas and the implementation of telemedicine are two strategies that could considerably mitigate out-of-pocket costs.

From a conservative perspective, it may appear that out-of-pocket healthcare expenses did not have a considerable impact in our study. However, by taking a broader view that more realistically reflects the circumstances of vulnerable and poor populations, including the double impact of both costs and lost income, we have been able to identify the economic impact on patients of the absence of healthcare networks located close to where they live and to see how this perpetuates the poverty of those who are affected by T. cruzi infection/ Chagas disease.

Out-of-pocket costs have a significant impact on the management and quality of life of patients who live with chronic disease. Limiting these costs would help patients adhere to their treatment and thus decrease complications.

Acknowledgments

Chagas Program team thanks the individuals that took part in this study by answering the survey, and that provided this valuable information. We would also thank Louise Burrows for her contribution by curating the text of this publication. The Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi) is grateful to its donors, public and private, who have provided funding to DNDi since its inception in 2003. A full list of DNDi’s donors can be found at .

http://www.dndi.org/donors/donors/.

References

- ILO, PAHO. El gasto de bolsillo en salud en América Latina y el Caribe: Razones de eficiencia para la extensión de la protección social en salud. Reun Reg Tripart la OIT con la Colab la OPS, México, 29/11 - 1/12/99 [Internet]. 1999;1–41. Available at: http://www.oitopsmexico99.org.pe.

- Hernández-Vásquez A, Vargas-Fernández R, Magallanes-Quevedo L, Bendezu-Quispe G. Análisis del gasto de bolsillo en medicamentos e insumos en Perú en 2007 y 2016. Medwave [Internet]. 2020 Mar 19 [cited 2022 Feb 15];20(02):e7833. Available at: /link.cgi/Medwave/Revisiones/Analisis/7833.act.

- Sauerborn R, Adams A, Hien M. Household strategies to cope with the economic costs of illness. Soc Sci Med. 1996 Aug;43(3):291-301. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre D, Thiede M, Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. What are the economic consequences for households of illness and of paying for health care in low- and middle-income country contexts? Soc Sci Med. 2006 Aug;43(3):291-301. Epub 2005 Aug 15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastos directos de bolsillo en salud: la necesidad de un análisis de género © Pan American Health Organization, 2021 – WHO/PAHO.

- Cid C, Flores G, Del Riego A, Fiztgerald J. Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible: impacto de la falta de protección financiera en salud en países de América Latina y el Caribe. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2021;45:e95. [CrossRef]

- Health at a Glance 2021. 2021 Nov 9 [cited 2022 Feb 15]; Available at: https://www.oecd- ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-2021_ae3016b9-en.

- Chang AY, Cowling K, Micah AE, Chapin A, Chen CS, Ikilezi G, et al. Past, present, and future of global health financing: A review of development assistance, government, out-of-pocket, and other private spending on health for 195 countries, 1995-2050. Lancet. 2019;393(10187):2233–60.

- Olivera, Mario J BG. Economic costs of Chagas disease in Colombia in 2017: A social perspective. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;196–201.

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, 2016. Resolución 3202 de 2016., https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/DE/DIJ/resolucion-3202-de-2016.pdf, Colombia. Accessed on May 10, 2021.

- Leatherman, T et al. 2014/11/01 - The reproduction of poverty and poor health in the production of health disparities in southern Peru -Vol 38 - Annals of Anthropological Practice.

- Herazo, R., Torres-Torres, F., Mantilla, C., Carillo, L. P., Cuervo, A., Camargo, M., Moreno, J. F., Forsyth, C., Vera, M. J., Díaz, R., & Marchiol, A. (2022). On-site experience of a project to increase access to diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease in high-risk endemic areas of Colombia. Acta tropica, 226, 106219. [CrossRef]

- El Congreso de Colombia. (2016). Ley estatutaria 1751 de 2015. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/proteccionsocial/Paginas/ley-estatutaria-de-salud.aspx. Accessed on May 10, 2022, available at: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Normatividad_Nuevo/Ley%201751%20de%202015.pdf.

- Petrera Pavone M, Jiménez Sánchez E. Determinantes del gasto de bolsillo en salud de la población pobre atendida en servicios de salud púbicos en Perú, 2010-2014. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2018;42:e20. [CrossRef]

- Estrategia para el acceso universal a la salud y la cobertura universal de salud. 53.° Consejo Directivo de la OPS, 66.ª sesión del Comité Regional de la OMS para las Américas, documento CD53/5, Rev. 2 (2014).

- WHA63 63.ª Asamblea Mundial de la Salud: resoluciones y decisiones; 2010https://www.paho.org/en/node/64044.

Chart 2.

The relationship between the focus of healthcare, out-of-pocket costs, and the costs and savings associated with the health system.

Chart 2.

The relationship between the focus of healthcare, out-of-pocket costs, and the costs and savings associated with the health system.

Chart 3.

Burden on patients and families.

Chart 3.

Burden on patients and families.

Table 1.

General profile of the patients surveyed.

Table 1.

General profile of the patients surveyed.

| VARIABLE |

SURVEYED PEOPLE (N=91) |

| |

N |

% |

| LOCATION |

|

|

| Mogotes |

30 |

33 |

| Soatá |

61 |

67 |

| GENDER |

|

| Female |

59 |

64.8 |

| Male |

32 |

35.2 |

| AGE GROUP (years) |

|

| <20 |

1 |

1.1 |

| 20 – 39 |

14 |

15.4 |

| 40 – 59 |

30 |

33 |

| >60 |

44 |

48.3 |

| No data |

2 |

2.2 |

| PLACE OF RESIDENCE |

|

| Rural |

51 |

56 |

| Urban |

40 |

44 |

| EDUCATION LEVEL |

|

| None |

12 |

13 |

| Elementary |

58 |

64 |

| Secondary |

15 |

17 |

| Technical/Trade |

2 |

2 |

| Professional |

1 |

1 |

| Other |

2 |

2 |

| No data |

1 |

1 |

| HEALTH INSURANCE REGIMEN |

|

| Subsidized |

83 |

91 |

| Contribution |

8 |

9 |

| HEAD OF FAMILY |

|

| Yes |

64 |

70 |

| No |

27 |

30 |

| COMORBIDITIESa |

|

| None |

45 |

49 |

| High blood pressure |

25 |

27 |

| Diabetes |

11 |

12 |

| Lung problems |

12 |

13 |

| Kidney failure |

2 |

2 |

| Other |

11 |

12 |

| More than 1 comorbidity |

17 |

19 |

| OCCUPATION |

|

| Housewife |

47 |

51.6 |

| Agriculture |

21 |

23.1 |

| Other |

8 |

8.8 |

| No data |

15 |

16.5 |

| DAILY INCOME (COP*) |

|

| None |

50 |

55 |

| 1000-5,999 |

15 |

16.5 |

| 6,000-14,999 |

5 |

5.5 |

| 15,000-49,999 |

8 |

8.8 |

| 50,000-100,000 |

3 |

3.3 |

| No data |

10 |

10.9 |

Table 2.

Education Level, daily income, and employment status according to gender.

Table 2.

Education Level, daily income, and employment status according to gender.

| VARIABLEa

|

GENDER |

P valueb

|

| |

Male (%) |

Female (%) |

|

| EDUCATIONAL LEVEL |

|

0.934 |

| None |

5 (16.1) |

7 (11.9) |

|

| Elementary |

20 (64.5) |

38 (64.4) |

|

| Secondary |

5 (16.1) |

10 (16.9) |

|

| Technical/Trade |

1 (3.3) |

1 (1.7) |

|

| Professional |

0 |

1 (1.7) |

|

| Other |

0 |

2 (3.4) |

|

| Total |

31 |

59 |

|

| EMPLOYMENT STATUS |

|

0.333 |

| Without a job |

13 (48.2) |

36 (62.1) |

|

| Informal |

12 (44.4) |

18 (31) |

|

| Salaried |

0 |

2 (3.5) |

|

| Retired |

0 |

1 (1.7) |

|

| Other |

2 (7.4) |

1 (1.7) |

|

| Total |

27 |

58 |

|

| DAILY INCOME (COP*) |

|

0.027 |

| None |

16 (55.2) |

34 (65.4) |

|

| 1000-5,999 |

5 (17.2) |

10 (19.2) |

|

| 6,000-14,999 |

0 |

5 (9.6) |

|

| 15,000-49,999 |

5 (17.2) |

3 (5.8) |

|

| 50,000-100,000 |

3 (10.4) |

0 |

|

| Total |

29 |

52 |

|

Table 4.

Differences in lost income between the two healthcare scenarios.

Table 4.

Differences in lost income between the two healthcare scenarios.

| VARIABLE |

Local primary care hospital (%)n=42/91 (46.1) |

Specialized reference hospital (%)n=33/64 (51.5) |

P valuea

|

| Lost income (COP*) |

|

0.259 |

| <5,000 |

3 (7.1) |

0 |

|

| 5,000 – 9,999 |

2 (4.8) |

1 (3) |

|

| 10,000 – 39,999 |

20 (47.6) |

12 (36.4) |

|

| 40,000 – 99,999 |

3 (7.1) |

3 (9.1) |

|

| >100,000 |

1 (2.4) |

4 (12.1) |

|

| No specific monetary data |

13 (31) |

13 (39.4) |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).