1. Introduction

Fermented foods with high nutritional value and scientifically demonstrated health benefits continue to attract attention. Multiple biochemical changes occur during fermentation that may increase nutritional value and lead to production of bioactive metabolites. Vinegar has long been used to treat diseases in both the East and West [

1]. The beneficial properties of vinegar include antioxidant [

2], antitumor [

3], hepatoprotective [

4], antidiabetic [

5], and antimicrobial [

6] activities. Vinegar production by the action of acetic acid bacteria (AAB) involves formation of a bacterial film on the surface of an alcoholic solution that ferments ethanol to acetic acid, in parallel with the generation of gluconic acid, glucuronic acid, polyphenols, vitamins, amino acids, and hydrolytic enzymes [

7,

8].

Acetic acid-producing bacteria are strictly aerobic Gram-negative bacteria of the

Acetobacteraceae family that inhabit warm and humid sites of flowers, fruits, insect digestive tracts, and fermented foods including vinegar, kefir, and kombucha [

9,

10,

11,

12]. They produce organic acids, aldehydes, and ketones through incomplete oxidative fermentation of sugars, alcohols, and sugar alcohols [

13]. Acetic acid bacteria are industrially relevant microorganisms that have been used for the production of fermented foods including vinegar, cosmetics, and medicines, and in the development of biofuel cells [

12,

14,

15]. One strength of AAB is an ability to use less biomass while producing large amounts of acetic acid as compared to other bacteria that form organic acids [

16]. The primary taste and aroma of vinegar products arises from AAB fermentation [

17,

18]. Among AAB, 19 genera have been reported to date, including

Acetobacter,

Gluconobacter,

Gluconacetibacter, and

Komagatacetibacter [

19].

Acetobacter is the main genus used in industrial vinegar production because of a high resistance to ethanol and acid [

20,

21].

Recently, as awareness of the benefits of vinegar has increased, more attention has been paid to research related to AAB in vinegar production. Moreover, with the implementation of the Nagoya Protocol in August 2018, the need for developing technology for resource recovery and formulation of indigenous bacteria has emerged to replace that of imported AAB. Most studies have only reported limited aspects of vinegar production by AAB, based on characterization of products, with none focusing on the bacteriological properties and bioactivities of AAB. Therefore, in order to reduce royalty payments due to the use of imported bacteria and contribute to the localization of AAB, we sought to discover functional AAB capable of differentiating and modernizing vinegar quality, and to identify the bacteriological characteristics useful for industrial application. We isolated AAB from farm-produced fermented vinegars with the aim of characterizing them in terms of bioactivities including antibacterial, antioxidant, antihypertensive, and antidiabetic effects. Our research successfully demonstrated bioactive characteristics that may facilitate the use of these AAB as seed strains for high-efficiency production of functional vinegar by harnessing their functional characteristics on a scientific basis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

Vinegar samples were obtained from Gangwon-do, Gyeonggi-do, Jeollabuk-do, and Gyeongsangbuk-do provinces in the Republic of Korea. The properties of the vinegar samples collected are listed in

Table 1. All samples were stored at 4 °C and screened for AAB isolates within 2–3 days of collection.

2.2. Isolation of Bacterial Strains

The AAB strains were isolated from farm-produced vinegars (

Table 1) by plating on YGC agar (5 g/L yeast extract, 30 g/L glucose, 10 g/L CaCO

3, 4% (v/v) ethanol, 2% (w/v) agar) [

22]. Each 100–200 µL sample of vinegars was spread onto YGC agar plates and incubated at 30 °C for 3 days. Representative colonies with a clear halo were picked from the plates, where the haloes indicate dissolving of CaCO

3 in the medium by the acetic acid produced. Selected colonies were streaked onto fresh plates and used in further experiments. Purified strains were stored at −80 °C in YGC broth with 80% glycerol. As control strains, three strains obtained from the Korean Agricultural Culture Collection (KACC) center were used:

Gluconacetobacter saccharivorans CV1, KACC 17057;

Acetobacter pomorum, KACC 11998; and

A. syzygii, KACC 12233.

2.3. Bacterial Culture Condition and Preparation for Analysis

The AAB strains were cultured in liquid medium comprising 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L glucose, 1% (v/v) glycerol, 0.2 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 1% (v/v) acetic acid containing 5% (v/v) ethanol at 30 °C for 7 days at 150 rpm using a shaking incubator (MMS-210; EYELA, Tokyo, Japan). For analysis, the culture broth was centrifugated at 10,000×g for 5 min, followed by collection of the supernatant.

2.4. Identification of Bacterial Strains

Strain identification was performed via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification using 16S rRNA sequencing. DNA was extracted using an AllPrep PowerFecal DNA/RNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and the 16S rRNA gene region was amplified using the universal primers 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). PCR was performed on an ABI PRISM 3730xl (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA), with reaction parameters of 30 cycles of denaturation at 96 °C for 10 s, annealing at 50 °C for 10 sec and extension at 60 °C for 3 min. The sequences obtained were aligned using the Advanced Basic Local Alignment Search Tool of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using MEGA software (version 6.0,

https://www.megasoftware.net). A phylogenetic tree was constructed from alignments using the neighbor-joining method, and the reliability of the inferred trees was assessed using a bootstrap test [

23].

2.5. Acetic Acid Production

Isolated AAB were evaluated for the ability to produce acetic acid on YGC medium containing different concentrations of ethanol (3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, and 15% (v/v)) using the potency index (PI) for assessment [

24]. After incubation at 30 °C for 96 h, a clear zone formed in the medium indicating the production of acetic acid. The clear zone diameter (

Supplementary Figure S1) was then used to assess the potency of each AAB. The diameters of the colonies formed by the isolates and the surrounding clear zones were measured, and the potency index (PI) was determined according to the following formula:

Bacteria with the highest PI were selected. To analyze the ability of AAB to produce acetic acid, liquid medium was used containing 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L glucose, 1% (v/v) glycerol, 0.2 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 1% (v/v) acetic acid containing different concentrations of ethanol (3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, and 15% (v/v)).

2.6. Bacterial Growth and Titratable Acidity

Growth of AAB was measured based on their optical density at 660 nm using a spectrophotometer (Gen5TM, BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Total acidity was determined by titration with 0.1 N NaOH using 1% phenolphthalein as indicator. The volume of NaOH used in the titration was expressed as the titratable acidity (%) for neutralizing acetic acid, as presented in the following equation:

where, 0.006 was the acetic acid equivalent.

2.7. Effect of Temperature on Growth

To analyze the effect of temperature on acetic acid production, a single colony was transferred to YGC agar containing 5% (v/v) ethanol. Plates were grown at 10, 20, 30, or 40 °C for seven days and the diameter of the clear zone was measured using a digital caliper at 3-day intervals.

2.8. Antibacterial Activity

The antibacterial activity of selected AAB strains against harmful Gram-positive (Bacillus cereus, KACC 10004; Staphylococcus aureus, ATCC 6538) and Gram-negative (Escherichia coli, KCTC 1309; Salmonella typhimurium, KCTC 41028) bacteria purchased from the Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC, KACC) and American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) was investigated using an agar diffusion method on solid medium. The test strains were activated for 16 h in tryptic soy broth (17 g/L pancreatic casein digest, 3 g/L papain soybean digest, 2.5 g/L glucose, 5 g/L NaCl, 2.5 g/L K2HPO4), and 1:1000 dilutions of each test strain were then spread on a 0.6% tryptic soy agar plate. Sterile 8 mm discs (Whatman plc, Maidstone, United Kingdom) were placed on the agar, and 40 µL of selected AAB strain cultures (optical density at 660 nm = 0.5) were inoculated onto the discs. After incubation for 24 h at 30 ℃, the diameter of each zone with clear inhibition was determined. Three replicates were used. Positive control values were obtained using 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/mL acetic acid.

2.9. Antioxidant Activity

Antioxidant activity for AAB strains was determined using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and 2,2′-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS, Sigma-Aldrich). Determination of radical scavenging activity of the samples was carried out using a previously reported method [

22,

25] with slight modifications. For the DPPH assay, a stock solution of 0.4 mM DPPH in absolute ethanol was prepared, and a working DPPH solution was prepared by dilution with absolute ethanol to an absorbance of 0.95–0.99 at 525 nm. For each measurement, 200 μL sample (standard dilution or ethanol blank) was mixed with 800 μL working solution and the solution was incubated in the dark for 90 min. The absorbance at 525 nm was then determined. For the ABTS assay, a stock solution of 2.6 mM K

2S

2O

8 and 7.4 mM ABTS diammonium salt was prepared in deionized water (dH

2O) and incubated in the dark for 24 h, then an ABTS working solution was prepared by dilution to an absorbance of 0.67–0.73 at 732 nm with phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4. Samples (50 μL standard dilution or dH

2O blank) were mixed with a 950 μL ABTS working solution for each measurement. The absorbance at 732 nm was then determined. All measurements were obtained in triplicate using a microplate reader (SpectraMax M2, Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). Antioxidant activity in each case was determined relative to control:

2.10. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibition

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibition was determined using the method of Cushman and Cheung [

26] with slight modifications. The method is based on the liberation of hippuric acid from hippuryl-L-histidyl-L-leucine (HHL) by ACE. For the assay, 50 µL sample supernatant was mixed with 50 µL 2.5 mM HHL in 450 mM sodium borate at pH 8.3, and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. The mixture was subsequently incubated at the same temperature for 40 min with 50 µL ACE (10 mU/mL). The reaction was terminated by addition of 250 µL of 1 N HCl. Ethyl acetate (1.5 mL) was added and the sample was mixed for 30 s. The sample was centrifuged at 10,000×g for 5 min and the supernatant (1.0 mL) was dried in a heating block at 100 °C then dissolved in 1.0 mL dH

2O. The absorbance at 228 nm was determined using a UV spectrophotometer (BioTek). An average of three readings was used to calculate ACE inhibition (%):

where S is sample absorbance in the presence of ACE inhibitor, C is control absorbance with dH

2O, and SB and CB are absorbance readings for sample and control blanks without ACE. Captopril (0.1%, (v/v)) was used as the positive control.

2.11. α-Glucosidase Inhibition

α-Glucosidase inhibition was determined using an α-glucosidase activity assay kit (Cat. No. MAK123, Sigma-Aldrich) based on the release of

p-nitrophenol by hydrolysis of

p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (α-NPG). A lack of detected activity was taken as 100% inhibition. For the assay, Master Reaction Mix (200 µL assay buffer, 8 µL α-NPG substrate) was mixed with 20 µL AAB supernatant and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. The absorbance of p-Nitrophenol was measured at 405 nm, and acetic acid (12.5 mg/mL) was used as a positive control. α-glucosidase inhibition was calculated as follows:

where A

405 (calibrator) is the absorbance for calibrator at 20 min and A

405 (water) is the absorbance for water at 20 min.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Three replicates of each experiment were carried out with the data reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was done through one-way analysis of variance using the Statistical Analysis System, v7.1 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Duncan's multiple range test. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Collected Vinegars

Among the eight types of fruit vinegar collected, apple vinegar from Hongcheon, Gangwon-do was made from wine with 9.5% (v/v) ethanol produced from 12 Brix apple juice samples. This vinegar was fermented at room temperature (25–28 °C) in a PET container and had 4.5% acidity. Omija (

Schisandra chinesis) vinegar from Seongnam, Gyeonggi-do, was prepared from three-year-old Omijacheong, and had 4.42% acidity. Pineapple and tomato vinegars from Seongnam were prepared from fruit wine (13% (v/v) ethanol) aged for two to three years, with acidities of 6.0 and 3.99%, respectively. These vinegars were fermented under controlled conditions at 20 °C in glass container. Apple vinegar from Yecheon, Gyeongsangbuk-do, was manufactured using stationary fermentation at 30 °C in a traditional jar (pottery) and had an acidity of 6.56%. Bokbunja (

Rubus coreanus) and apple vinegar from Gochang, Jeollabuk-do, were fermented statically at 30 °C in traditional jar (pottery) and had lower acidities than other vinegars (5.8, 2.8, and 4.4%). The collected vinegars ranged from one month to one year old and were produced in a farmhouse, then stored in an aging room after fermentation was completed (

Table 1).

3.2. Identification of Isolates by 16S rRNA Sequencing

Acetic acid bacteria were successfully isolated from seven samples of fruit vinegar (other than tomato) using CaCO

3 medium. A total of 256 presumptive AAB strains were isolated. Almost all isolates were capable of producing acid, as a clear zone formed around all colonies on CaCO

3-ethanol agar. Alcoholic stress conditions were established on agar media with different ethanol concentrations. From the 66 isolates tested for acetic acid production in ethanol medium containing 3–15% ethanol, 20 strains produced substantially higher acetic acid content than the control strains (

G. saccharivorans CV1,

A. pomorum 11998, and

A. syzygii 12233) after four days of incubation in ethanol medium. Almost all AAB tolerated ethanol concentrations up to 12% (

Table 2 and

Supplementary Figure S1). Seven strains were tested for acid production over time in liquid cultures containing different ethanol concentrations along with 1% acetic acid. Productivity of AAB strains isolated in this work was the highest, with 9% acetic acid production (

Supplementary Table S1).

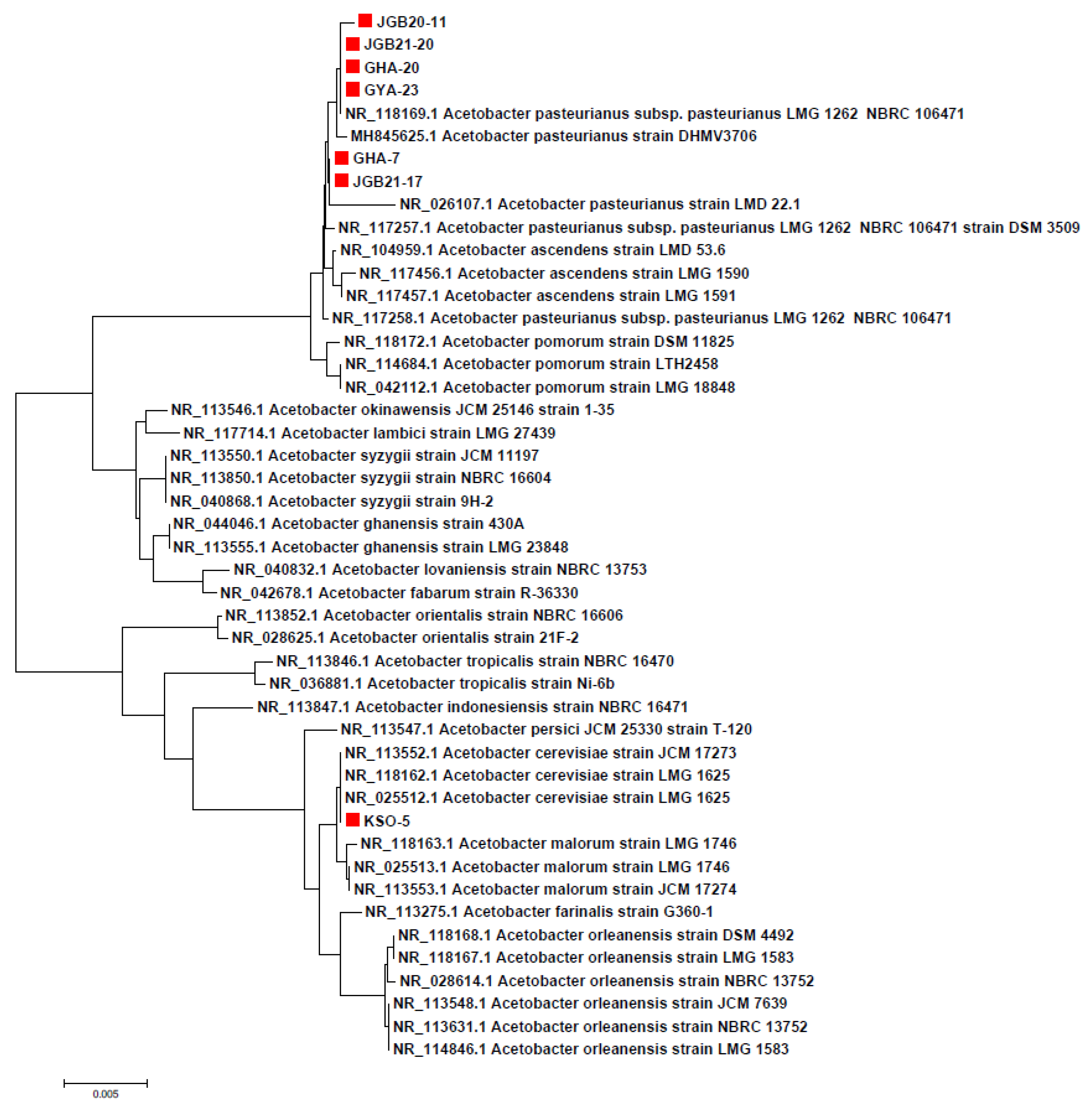

Diversity was observed in the isolated AAB strains. Seven AAB strains were identified by 16S rRNA sequencing, with sequencing analysis revealing two different AAB species,

A. pasteurianus and

A. cerevisiae (

Table 3).

The selected strains had more than 99% similarity based on 16S rRNA sequence analysis. The sequences were used to construct a phylogenetic tree that clearly showed the groupings of the samples and their relatedness within the

Acetobacteraceae family (

Figure 1). The two species identified here are commonly associated with vinegar production [

27].

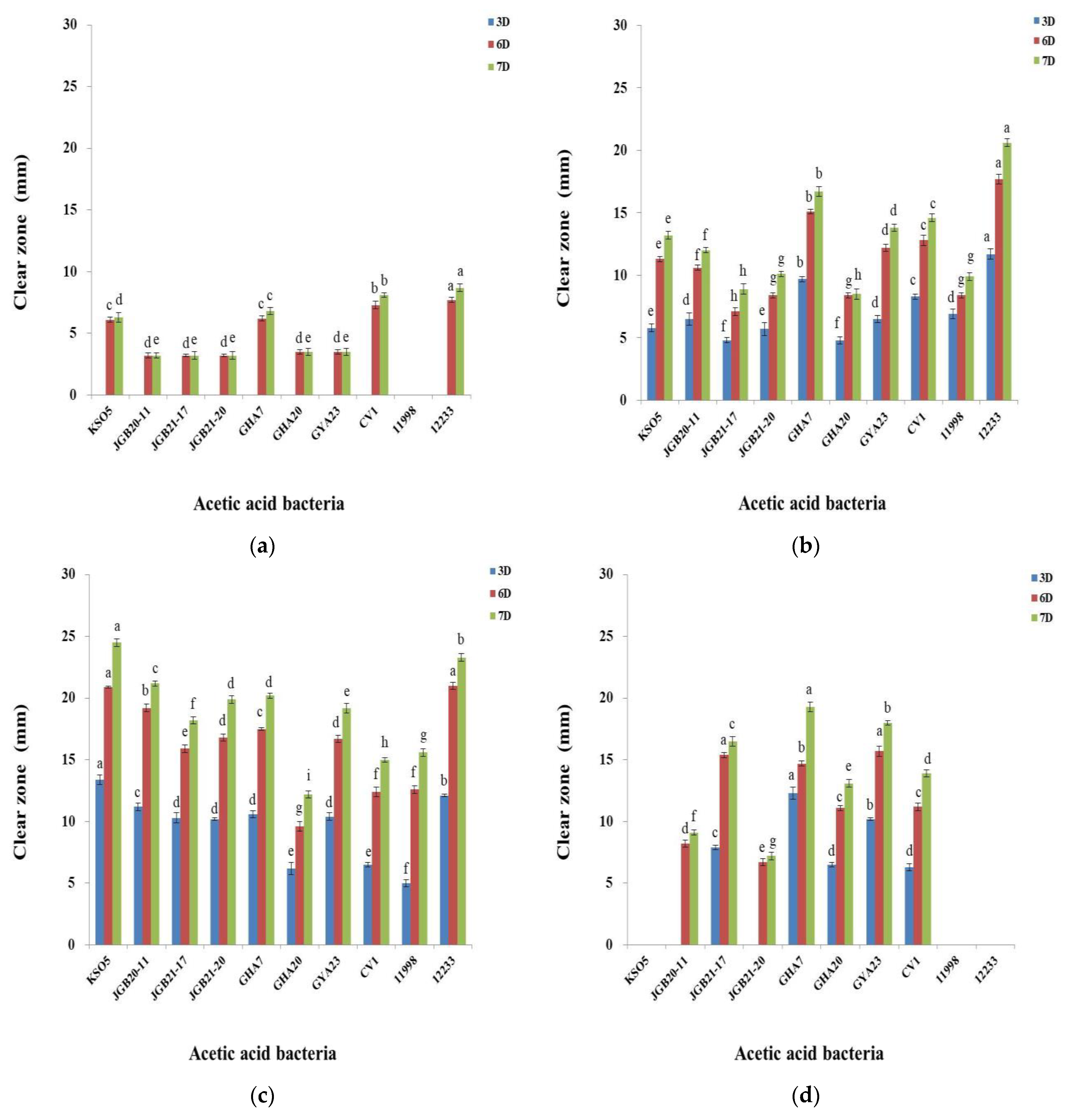

3.3. Effect of Temperature on Growth

Temperature optimization is important for bacterial culture, as bacterial inactivation can occur above a fixed temperature due to denaturation of essential enzymes, membrane damage with loss of cellular components, and increased sensitivity to the toxic effects of metabolic products including acetic acid [

28]. To select AAB suitable as starter strains for fermentation, we evaluated the growth rate and acetic acid yield of seven isolates at different temperatures (10–40 °C). All strains showed acidification capacity with halos around agar colonies, but at different levels depending on the incubation temperature across seven days (

Figure 2). The seven AAB strains selected did not grow well at low temperatures (10 or 20 °C) due to a long adaptation time. As reported by Adachi et al. [

29], AAB are usually mesophilic with optimum growth temperatures between 25 and 30 °C. The KSO 5, JGB 20-11, and JGB 21-20 strains showed a high acidification capacity at 30 °C, while the GHA 20 strain showed a capacity to grow at 40 °C. In terms of acidification capacity at 40 °C, JGB 21-17, GHA 7, and GYA 23 strains had an acid zone diameter at 40 °C that was at least 90% of that shown at 30 °C. Acidification results from the bioconversion of ethanol to acetic acid, an exothermic reaction that can result in heat accumulation [

30]. Increasing temperatures in recent years pose a serious challenge to the fermentation industry because large cooling systems are required to maintain optimum temperatures. The production of vinegar using thermotolerant AAB has attracted interest because of potential economic benefits. Therefore, AAB strains isolated in this study that can grow at 40 °C are expected to be highly useful in the vinegar industry as starter strains capable of strong acidification and improved fermentation.

3.4. Antibacterial Activity

Antibacterial effects of the AAB strains isolated against bacteria causing food spoilage were tested using diffusion assays. The results are presented in

Table 4. All AAB strains showed antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive (

Bacillus cereus and

Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative bacteria (

Escherichia coli and

Salmonella typhimurium). Comparing the antimicrobial effect of the strains with those for different concentrations of acetic acid, isolates showed an activity range comparable with 12.5–25 mg/mL acetic acid (

Supplementary Figure S2 and

Table S2). Antimicrobial activity was higher against Gram-positive bacteria including

S. aureus, than against Gram-negative bacteria. It has been reported that the outer membrane of Gram-positive bacteria is more sensitive to antimicrobial agents than that of Gram-negative bacteria [

31]. Acetic acid produced by AAB can diffuse across bacterial membranes based on an equilibrium between ionized and non-ionized forms in parallel with the lowering of pH of the surrounding medium. Acidification of the cytoplasm causes morphological disruption of harmful bacteria and leakage of intracellular components, as well as the induction of protein unfolding along with membrane and DNA damage [

32,

33,

34]. The antibacterial effect of acetic acid on different types of pathogenic bacteria has been increasingly relied upon in food safety for its preservative effects. Acetic acid is a substance generally recognized as safe by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and has been approved as a food additive by the European Commission, the Food and Agriculture Organization, the World Health Organization, and the FDA [

35]. Sakhare et al. [

36] investigated the use of acetic acid as an antimicrobial agent in meat, including poultry, beef, and pork, to extend its shelf life, as well as for the decontamination of bacteria including

Salmonella spp. and

E.coli. We thus assessed the possible use of antimicrobials derived from the AAB strains isolated here for application in the vinegar industry.

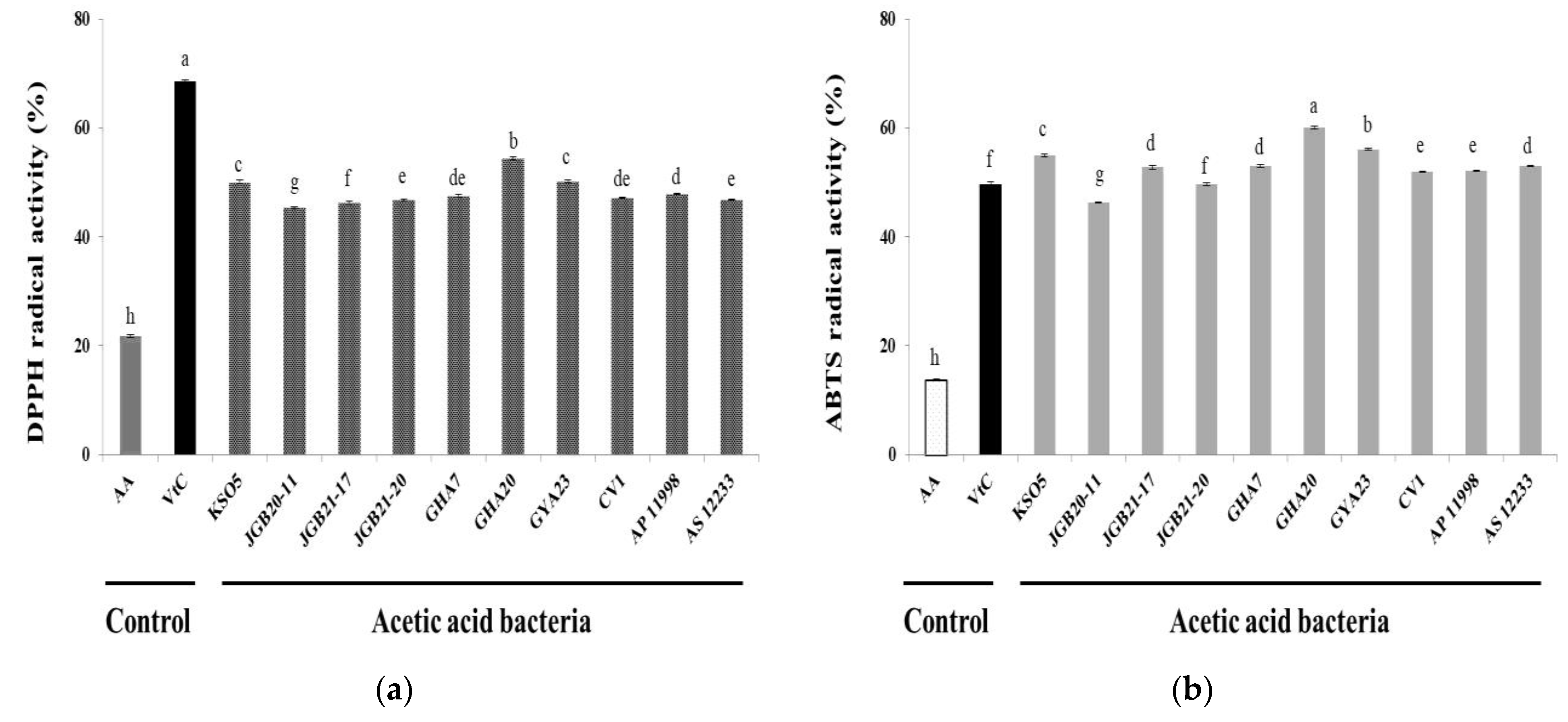

3.5. Antioxidant Activity

Antioxidants are known for their ability to limit radical reactions by transferring hydrogen atoms or electrons and interrupting oxidative chain reactions. Assays using DPPH and ABTS measure the release of an electron to ROO•, converting it to an anion (ROO−), resulting in an absorbance decrease in solution that reflects the concentration of the antioxidant. The mechanism involves loss of a proton from the antioxidant, followed by electron transfer to the radical, which then reacts with the proton. This is influenced by proton affinity and electron transfer enthalpy. The DPPH radical reacts preferentially via a proton transfer mechanism in solvents such as ethanol and methanol, while the ABTS radical does the same in aqueous solutions.

The antioxidant properties of isolated AAB strains rely on the antioxidant molecules of AAB that have scavenging activity against free radicals [

37]. Generation of free radicals leads to multiple chain reactions that can cause cell damage and death. The balance between free radicals and antioxidant molecules determines the level of oxidative stress [

38].

Figure 3 shows antioxidant activities of the isolated AAB strains measured using DPPH and ABTS. The scavenging capacity for DPPH and ABTS of the AAB strains was enhanced compared with that of the negative control (1% acetic acid). For the AAB strains, DPPH scavenging was approximately 50%, whereas that for the control was 22%. The value for the AAB strains was twice as high as that of the control and similar to that of 0.05% ascorbic acid (68.6%) (

Figure 3a). The ABTS scavenging activity of the AAB strains was four times higher than that of the negative control (13.7%) and higher than that of ascorbic acid (49.7%) (

Figure 3b). Although scavenging of DPPH and ABTS radicals was different due to a difference in reactivity between the two compounds, the isolated AAB strains showed a correlation between antioxidant activity and organic acid levels, as previously reported by Xu et al. [

37]. These findings suggest that acetic acid fermentation with various food materials increases their bioactive potential and promotes synergy between fermentation metabolites and microorganisms, leading to the production of compounds of interest such as polyphenols. These results represent preliminary findings that will aid in the evaluation of the bioactive potential of acetic acid fermentation by isolated AAB strains.

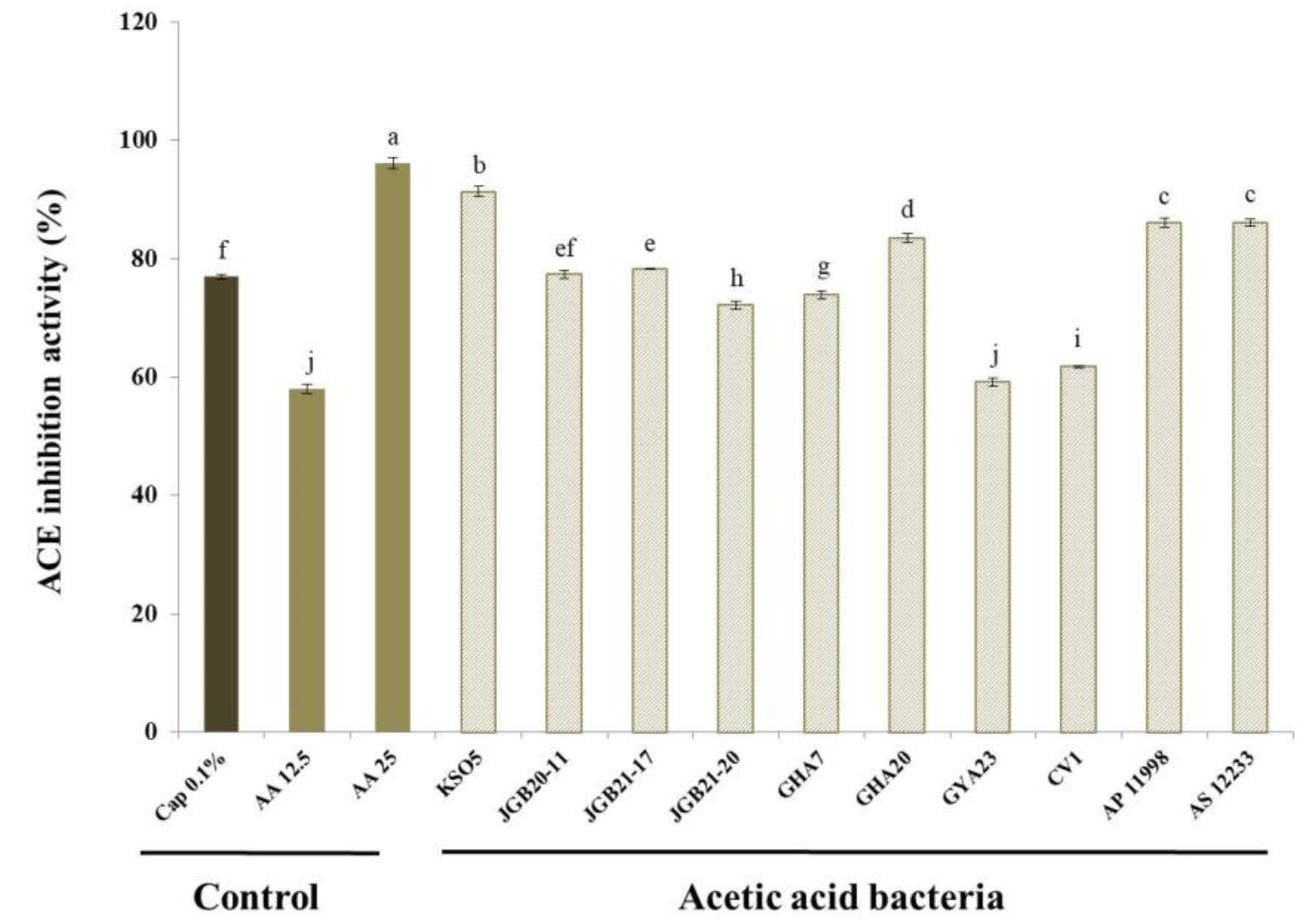

3.6. ACE Inhibition

Angiotensin-converting enzyme is a key enzyme in the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, converting angiotensin I to angiotensin II (Ang II) to exercise blood pressure control. Ang II binds to A-II receptors, constricts arteries and arterioles, excites the adrenal cortex, and promotes aldosterone release. Ultimately, this causes an increase in blood pressure [

39]. Inhibition of ACE alleviates high blood pressure by minimizing Ang II formation. Captopril is an effective synthetic antihypertensive drug that inhibits ACE [

40].

Figure 4 shows ACE inhibition by culture supernatants of the isolated AAB strains. Six of the strains isolated (excluding GYA 23) had higher ACE inhibitory activity than the 0.1% captopril positive control (76.9%). The KSO 5 strain showed the highest level of inhibition (91.3%). For acetic acid, the main product of AAB, ACE inhibitory activity was 58 and 96.0% at 12.5 and 25 mg/mL acetic acid, respectively. Some of the beneficial effects of acetic acid produced by fermentation have been attributed to ACE inhibition. Acetic acid is a carboxylic acid, and some carboxylic acids, including citric, docosahexaenoic, and tartaric acid, are known for antihypertensive activity [

41,

42,

43,

44]. The ACE2 receptor is a high-affinity receptor for the viral spike protein of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) [

45,

46]. For this reason, ACE inhibitors and Ang II receptor blockers have been considered for the treatment of viral infections. As synthetic ACE inhibitors are effective antihypertensive drugs, they may cause adverse effects. Thus, there is growing interest in identifying ACE inhibitors in natural products as alternatives to synthetic drugs. Vinegar may play a role in lowering blood pressure, and various studies have tested this effect [

47,

48]. Based on the results shown in

Figure 4, these strains are expected to be highly useful sources of ACE inhibitors.

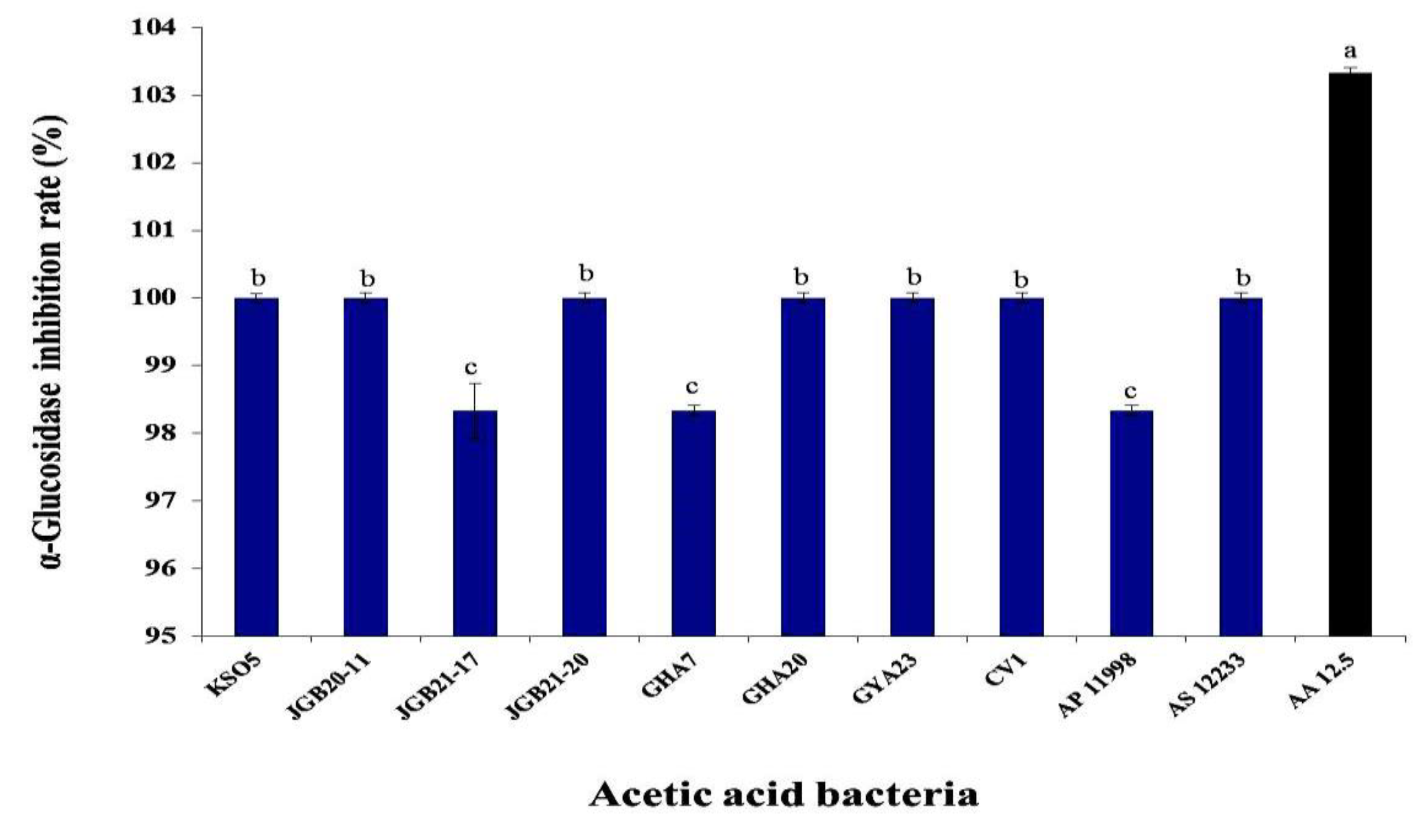

3.7. α-Glucosidase Inhibition

α-D-Glucosidase is a glucohydrolase that acts on (1→4) glucosidic bonds and is located in the brush border of the small intestine. Hydrolysis of terminal, non-reducing (1→4)-linked α-D-glucose units results in release of D-glucose. The liberated glucose is absorbed in the gut, resulting in postprandial hyperglycemia. Inhibition of intestinal α-glucosidase can significantly decrease the postprandial increase in blood glucose levels after carbohydrate intake by delaying carbohydrate hydrolysis and absorption. Therefore, inhibition of this enzyme can be important in the management of hyperglycemia linked to type 2 diabetes [

49,

50,

51]. Some antidiabetic drugs inhibit α-glucosidase activity. Although efficient in suppressing the rise in blood glucose levels in many patients, there are undesirable side effects associated with the continuous use of antidiabetic drugs [

52,

53]. Thus, natural inhibitors of α-glucosidase with no adverse or unwanted secondary effects are required.

The effects of AAB on α-glucosidase inhibition are presented in

Figure 5. The inhibition capacity of AAB was determined to be 103% that of 12.5 mg/mL acetic acid (AA 12.5) as the positive control. Most strains showed inhibitory activity greater than that of the positive control, with the exception of 98.3% inhibition for the JGB 21-17 and GHA 7 strains. Acetic acid bacteria are candidate strains with good functionality and potential health benefits. For example, the α-glucosidase inhibitory ability of kkujippong vinegar produced using AAB was previously shown to be 91.4% (after 72-h fermentation) [

54]. Acetic acid, the main component produced by AAB, breaks down lactic acid to relieve fatigue and decomposes fat to help control weight. Weight control contributes significantly to improving blood glucose [

55].

4. Conclusions

This study evaluated the functional characteristics of seven AAB strains isolated from farm-produced fermented fruit vinegars. The seven bacterial strains exhibited high acetic acid production and were identified as members of A. cerevisiae and A. pasteurianus. The high temperature tolerance of some of the strains is expected to be useful for the vinegar industry. The harmful bacterium S. aureus, which can cause spoilage and contribute to the incidence of foodborne diseases, was highly susceptible to the antibacterial activity of the AAB strains. High antioxidant and ACE inhibitory activities were also observed, along with high α-glucosidase inhibition. Our results suggest that the seven isolated strains have a potential use in the industrial sector as well as in the production of functional foods. By using excellent indigenous AAB in the vinegar industry, we want to increase the utilization value of domestic AAB and reduce production cost.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be. Figure S1: Ability of AAB isolates to produce acetic acid in CaCO3 medium with different levels of ethanol (3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, and 15% (v/v)). Figure S2: Images of clear zones and calibration curves of acetic acid indicating quantitative antibacterial activity of selected AAB strains. Table S1: Acetic acid production over a time course of days in liquid medium containing 5% (v/v) ethanol and 1% (v/v) acetic acid. Table S2: Quantitative antibacterial activity of selected AAB strains using calibration curve of acetic acid.

Author Contributions

This work was carried out in collaboration with all authors. S.H.K. and S.-H.Y.: designed the study. S.H.K.: performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. W.-S.J. and S.-Y.K.: managed the analyses of the study and literature searches. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Program for Agricultural Science and Technology Development (Project No. PJ0141610) and the National Institute of Agricultural Science, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www. Editage. Co. kr) for English languge editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.Y.; Gwon, H.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Yeo, S.H. Determination of quality characteristics by the reproduction of grain vinegars reported in ancient literature. Korean J. Food Preserv. 2020, 27, 859–871. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, X. Hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects of freeze-dried powder of Shanxi mature vinegar in hyperlipidaemic mice. Food Sci. 2015, 36, 141–151.

- Seki, T.; Morimura, S.; Shigematsu, T.; Maeda, H.; Kida, K. Antitumor activity of rice-shochu post-distillation slurry and vinegar produced from the post-distillation slurry via oral administration in a mouse model. BioFactors. 2004, 22, 103–105. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, T.; Giudici, P.; Chen, F. Vinegar functions on health: Constituents, sources, and formation mechanisms. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 1124–1138. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-K.; Choi, S.-R.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Park, K.-U.; Kwon, S.-H.; Seo, K.-I. Quality characteristics and anti-diabetic effect of yacon vinegar. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 41, 79–86. [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.M.; Fang, T.J. Survival of Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium in iceberg lettuce and the antimicrobial effect of rice vinegar against E. coli O157. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 745–751. [CrossRef]

- Valduga, A.T., At. T; Gonҁcalves, I. L.; Magri, E.; Delalibera-Finzer, J. R. Chemistry, pharmacology and new trends in traditional functional and medicinal beverages. Food Res. Int. 2018, 120, 478–503. [CrossRef]

- Sainz, F.; Navarro, D.; Mateo, E.; Torija, M.J.; Mas, A. Comparison of d-gluconic acid production in selected strains of acetic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 222, 40–47. [CrossRef]

- Chouaia, B.; Gaiarsa, S.; Crotti, E.; Comandatore, F.; Degli Esposti, M.; Ricci, I.; Alma, A.; Favia, G.; Bandi, C.; Daffonchio, D. Acetic acid bacteria genomes reveal functional traits for adaptation to life in insect guts. Genome Biol. Evol. 2014, 6, 912–920. [CrossRef]

- Kersters, K.; Lisdiyanti, P.; Komagata, K.; Swings, J. The family Acetobacteraceae: The genera Acetobacter, Acidomonas, Asaia, Gluconacetobacter, Gluconobacter, and Kozakia. The Prokaryotes. 2006, 5, 163–200. [CrossRef]

- De Roos, J.; De Vuyst, L. Acetic acid bacteria in fermented foods and beverages. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 49, 115–119. [CrossRef]

- Saichana, N.; Matsushita, K.; Adachi, O.; Frébort, I.; Frebortova, J. Acetic acid bacteria: A group of bacteria with versatile biotechnological applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1260–1271. [CrossRef]

- Adachi, O.; Fujii, Y.; Ano, Y.; Moonmangmee, D.; Toyama, H.; Shinagawa, E.; Theeragool, G.; Lotong, N.; Matsushita, K. Membrane-bound sugar alcohol dehydrogenase in acetic acid bacteria catalyzes L-ribulose formation and NAD-dependent ribitol dehydrogenase independent of the oxidative fermentation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001, 65, 115–125. [CrossRef]

- Gullo, M.; Verzelloni, E.; Canonico, M. Aerobic submerged fermentation by acetic acid bacteria for vinegar production: Process and biotechnological aspects. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 1571–1579. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.M.; Zannini, E.; Wilkinson, S.; Daenen, L.; Arendt, E.K. Physiology of acetic acid bacteria and their role in vinegar and fermented beverages. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 587–625. [CrossRef]

- López-Garzón, C.S.; Straathof, A.J.J. Recovery of carboxylic acids produced by fermentation. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 873–904. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; Zhang, J.; Bao, J. Fermentative production of high titer gluconic and xylonic acids from corn stover feedstock by Gluconobacter oxydans and techno-economic analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 219, 123–131. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chang, Y.; Xie, S.; Song, J.; Wang, M. Impacts of bioprocess engineering on product formation by Acetobacter pasteurianus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 2535–2541. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, H. Classification of acetic acid bacteria and their acid resistant mechanism. AMB Expr. 2021, 11, 29. [CrossRef]

- Kanchanarach, W.; Theeragool, G.; Inoue, T.; Yakushi, T.; Adachi, O.; Matsushita, K. Acetic acid fermentation of Acetobacter pasteurianus: Relationship between acetic acid resistance and pellicle polysaccharide formation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 74, 1591–1597. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.J.; Ma, Y.K.; Zhang, F.F.; Chen, F.S. Biodiversity of yeasts, lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria in the fermentation of “Shanxi aged vinegar”, a traditional Chinese vinegar. Food Microbiol. 2012, 30, 289–297. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.; Jeong, W.S.; Gwon, H.; Kim, S.Y.; Yeo, S. Culture and function-related characteristics of six acetic acid bacterial strains isolated from farm-made fermented vinegars. Korean J. Food Preserv. 2022, 29, 142–156. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [CrossRef]

- Ei-El-Askri, T.; Yatim, M.; Sehli, Y.; Rahou, A.; Belhaj, A.; Castro, R.; Durán-Guerrero, E.; Hafidi, M.; Zouhair, R. Screening and characterization of new Acetobacter fabarum and Acetobacter pasteurianus strains with high ethanol-thermo tolerance and the optimization of acetic acid production. Microorganisms. 2022, 10, 1741. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.X.; Zhang, M.; Xie, B.J. Components and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide conjugate from green tea. Food Chem. 2005, 90, 17–21. [CrossRef]

- Cushman, D.W.; Cheung, H.S. Spectrophotometric assay and properties of the angiotensin-converting enzyme of rabbit lung. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1971, 20, 1637–1648. [CrossRef]

- Luzón-Quintana, L.M.; Castro, R.; Durán-Guerrero, E. Biotechnological processes in fruit vinegar production. Foods. 2021, 10, 945. [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, S.M.; Rasooli, I.; Beheshti-Maal, K. Isolation characterization and optimization of indigenous acetic acid bacteria and evaluation of their preservation methods. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2010, 2, 38–45. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22347549.

- Adachi, O.; Moonmangmee, D.; Toyama, H.; Yamada, M.; Shinagawa, E.; Matsushita, K. New developments in oxidative fermentation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 60, 643–653. [CrossRef]

- Moonmangmee, D.; Adachi, O.; Ano, Y.; Shinagawa, E.; Toyama, H.; Theeragool, G.; Lotong, N.; Matsushita, K. Isolation and characterization of thermotolerant Gluconobacter strains catalyzing oxidative fermentation at higher temperatures. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2000, 64, 2306–2315. [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Kang, J.; Ping, W. Effect of acetic acid on bacteriocin production by Gram-positive bacteria. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1341–1348. [CrossRef]

- Axe, D.D.; Bailey, J.E. Transport of lactate and acetate through the energized cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1995, 47, 8–19. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, S.; Kishi, M.; Yamagami, K.; Okada, S.; Abe, K.; Misaka, T. The use of mammalian cultured cells loaded with a fluorescent dye shows specific membrane penetration of undissociated acetic acid. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2012, 76, 523–529. [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.B. Another explanation for the toxicity of fermentation acids at low pH: Anion accumulation versus uncoupling. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1992, 73, 363–370. [CrossRef]

- Surekha, M.; Robinson, R.K.; Batt, C.A.; Patel, C.; Reddy, S.M. Preservatives classification and properties. In Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology, Academic Press; New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 1710–1717. [CrossRef]

- Sakhare, P.Z.; Sachindra, N.M.; Yashoda, K.P.; Narasimha Rao, D.N. Efficacy of intermittent decontamination treatments during processing in reducing the microbial load on the broiler chicken carcass. Food Control. 1999, 10, 189–194. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Hong, J.H.; Kim, D.; Jin, Y.H.; Pawluk, A.M.; Mah, J.H. Evaluation of bioactive compounds and antioxidative activity of fermented green tea produced via one- and two-step fermentation. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022, 11, 1425. [CrossRef]

- Ivanišová, E.; Meňhartová, K.; Terentjeva, M.; Harangozo, Ľ.; Kántor, A.; Kačániová, M. The evaluation of chemical antioxidant, antimicrobial and sensory properties of kombucha tea beverage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 1840–1846. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.; Acharya, K.R. ACE for all-a molecular perspective. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2014, 8, 195–210. [CrossRef]

- Vermeirssen, V.; Van Camp, J.; Verstraete, W. Optimization and validation of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition assay for the screening of bioactive peptides. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods. 2002, 51, 75–87. [CrossRef]

- Kondo, S.; Tayama, K.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Ikeda, K.; Yamori, Y. Antihypertensice effects of acetic acid and vinegar on spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001, 65, 2690–2694. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, R.; Ahmad, M.; Naz, A.; Siddiqui, H.; Ahmad, S.I.; Faizi, S. Hypertensive and toxicological study of citric acid and other constituents fromtagetes pathla roots. Arch. Pharm. Res. (Seoul). 2004, 27, 1037–1042. [CrossRef]

- Engler, M.M.; Engler, M.B.; Pierson, D.M.; Molteni, L.B.; Molteni, A. Effects of docosahexaenoic acid on vascular pathology and reactivity in hypertension. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 2003, 228, 299–307. [CrossRef]

- Kousar, M.; Salma, U.; Khan, T.; Shah, A.J. Antihypertensive potential of tartartic acid and exploration of underlying mechanistic pathways. Dose-Response. 2022, 20, 15593258221135728. [CrossRef]

- Caravaca, P.; Morán, L.; Dolores, M.; Delgado, J. The renin-angioensin-aldosterone system and COVID-19. Clin. Implic. 2020, 20, 27–32. [CrossRef]

- Coto, E.; Avanzas, P.; Gómez, J. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and coronavirus disease 2019. Eur. Cardiol. 2021, 16, e07. [CrossRef]

- Elkhtab, E.; Ei-El-Alfy, M.; Shenana, M.; Mohamed, A.; Yousef, A.E. New potentially antihypertensive peptides liberated in milk during fermentation with selected acid bacteria and kombucha cultures. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 9508–9520. [CrossRef]

- Vitas, J.; Vukmanovic, S.; Cakarevic, J.; Popovic, L.; Malbasa, R. Kombucha fermentation of six medicinal herbs: Chemical profile and biological activity. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2020, 26, 157–170. [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Nguyen, T.H.; Kurihara, H.; Kim, S.M. α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of bromophenol purified from the red alga Polyopes lancifolia. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, H145–H150. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.I.; Apostolidis, E.; Shetty, K. In vitro studies of eggplant (Solanum melongena) phenolics as inhibitors of key enzymes relevant for type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 2981–2988. [CrossRef]

- Shinde, J.; Taldone, T.; Barletta, M.; Kunaparaju, N.; Hu, B.; Kumar, S.; Placido, J.; Zito, S.W. α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of Syaygium cumini (Linn.) skeels seed kernel in vitro and in Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats. Carbohydr. Res. 2008, 343, 1278–1281. [CrossRef]

- Etxeberria, U.; de la Garza, A.L.; Campión, J.; Martínez, J.A.; Milagro, F.I. Antidiabetic effects of natural plant extracts via inhibition of carbohydrate hydrolysis enzymes with emphasis on pancreatic alpha amylase. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2012, 16, 269–297. [CrossRef]

- Van de Laar, F.A. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors in the early treatment of type 2 diabetes. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2008, 4, 1189–1195. [CrossRef]

- Yim, E.J.; Jo, S.W.; Lee, E.S.; Park, H.S.; Ryu, M.S.; Uhm, T.B.; Kim, H.Y.; Cho, S.H. Fermentation characteristics of mulberry (Cudrania tricuspidata) fruit venigar produced by acetic acid bacteria isolated from traditional fermented foods. Korean J. Food Preserv. 2015, 22, 108–118. [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.H.; Lai, C.S.; Wang, H.; Lo, C.Y.; Ho, C.T.; Li, S.M. Black tea in chemo-prevention of cancer and other human diseases. Food Sci. Hum. 2013, 2, 12–21. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).