1. Introduction

The application of sensor technologies in agriculture is having an increasing role in measuring grain yield potential and grain quality throughout the cropping season. Important global arable crops include wheat, maize, canola, rice, soybean, and barley due to their nutritional importance, functional properties, and commodity value. Grain quality of commercially grown crops is influenced by a range of factors including cultivation practices, environment, harvest timing, grain handling, storage management and transportation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Spatial variation observed in grain yields can be due to soil type, topography, and interactions with environment (e.g., frost and water availability) within and across fields and farms and is well recognized as a driver of variation in grain quality. In addition, with increasing likelihood of extreme events and biotic pressures associated with climate change, it will be more challenging to maintain grain quality in future environments. Although growers currently manage these variations through better-adaptive cultivars, management practices and in-field sensors could provide improvements in managing grain quality and ultimately, profits, by providing information that would allow identification and segregation for grain quality by quantifying variation in quality obtained from the field. This would benefit end-users and add value to the farming enterprise.

Grain quality is defined by a range of physical and compositional properties, where the end-use dictates the grain and compositional traits and market potential. Grain quality has traditionally been measured post-farmgate when growers deliver to grain receival agents, and the load is subsampled and tested within a clean testing environment such as a testing station or laboratory using benchtop instrumentation and human visual inspection. Grain quality when received by grain receival agents is graded using two approaches: firstly, subjective procedures undertaken by trained operators (grain inspectors) assessing visual traits, including stained, cracked, defective grain and contaminants; and secondly objectively using standardised instrumentation, such as sieves to determine grain size and near infrared spectroscopy (NIR) to determine composition, such as protein and moisture concentration. Key traits used in valuing and trading grain include the percentage of small grain (screenings), foreign material (unable to be processed, milled or malted), contaminates, sprouted, stained or discoloured grain, broken, damaged or distorted grain, presence of insects or mould, test weight, or composition including moisture concentration, protein concentration, low levels of aflatoxins and a high Hagberg falling number test [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Many of these traits are measured as a % per weight of samples subsampled from the grain load. Manufacturers of end-product determine the specifications or limits associated with these quality traits as grain outside the set specifications impacts the end-product quality. For example, small, shrivelled grain that may be high in protein concentration would be undesirable when processing food products from wheat as these impact on flour yield, baking loaf volume, and dough rheology characteristics as reviewed by [

12].

The application of sensor technologies pre-harvest is increasingly being incorporated into farming enterprises to determine the impact of environmental factors on grain production and yield. For example, field sensors are used to discern spatial and temporal information throughout the production system including soil type variation and nitrogen inputs (e.g., electromagnetic conductivity [EM38]), growth habit (Normalised Difference Vegetative Index [NDVI] and relative greenness [SPAD]) [

13,

14], nutritional status (Canopy Chlorophyl Content Index [CCCI]) [

15], the impact of abiotic stresses such as frost and heat [

4,

16], and biotics where RGB imaging is used to target spraying weeds [

17]. The next transition is to utilise sensors to record reliable, efficient, and relevant data associated with grain quality. Downgrades in grain quality can be caused by heat waves and frost during grain filling, drought, disease and the presence of weeds or other contaminants. Previous studies have shown that stresses such as high temperature, chilling, water stress (associated with soil type) and disease can vary spatially within grower’s fields [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Studies linking spatial distribution of stress events to grain quality have predominantly related to protein and protein quality in wheat [

22,

23]. But limitations remain as to how sensor technologies can be applied to all crop types for a range of grain quality traits.

The monitoring of grain quality, pre- or post-harvest is currently limited by the costs of the sensors, their availability, and development of algorithms for measuring key grain quality traits. A deeper understanding of the grower’s perspective; in particular, the key quality traits of relevance to their farm business is required to guide priorities when developing these applications. Consideration must also be given to a range of practical issues associated with deploying sensors on-farm and managing the logistics of a segregated grain supply chain. Previous studies have highlighted some opportunities to improve grower returns through segregating cereals at harvest [

2,

24,

25,

26], the economics of actively managing grain quality on-farm needs to be quantified at the practical level.

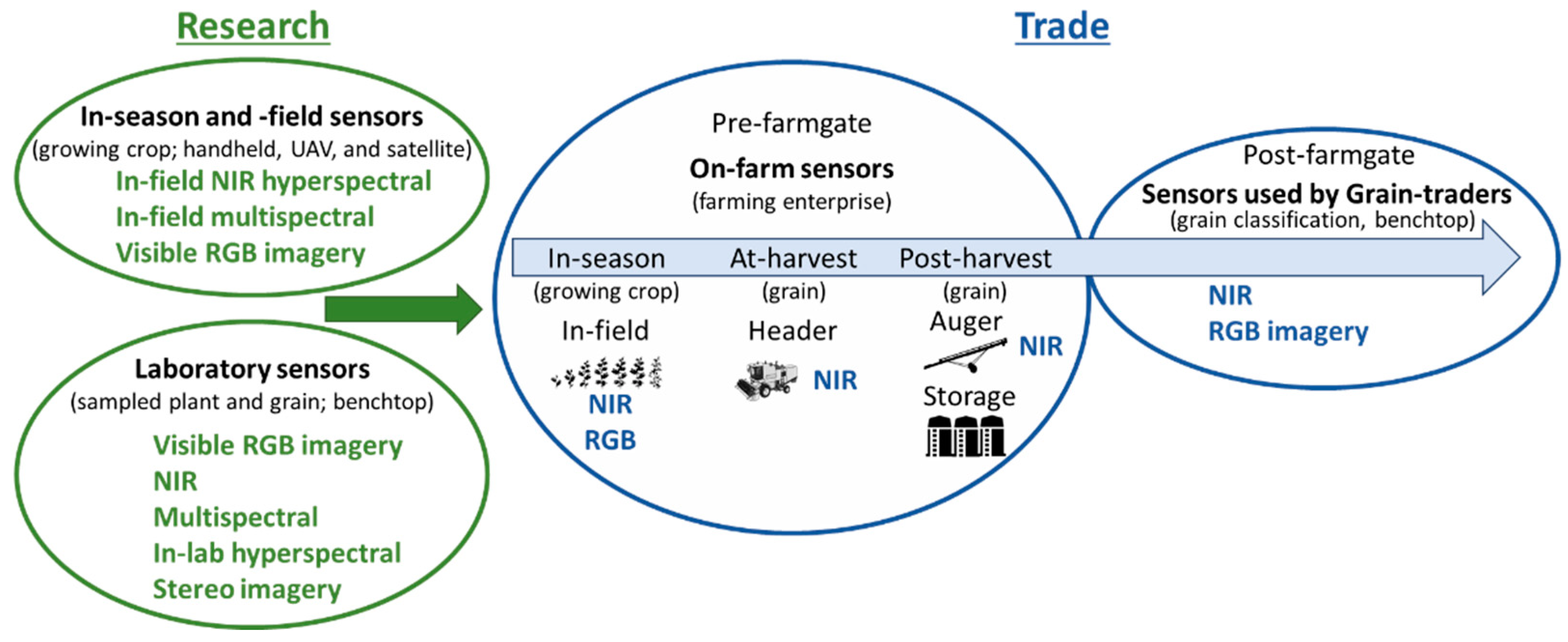

Given the speed of sensor development and miniaturisation, sensor technologies are commercially available that produce reliable data in an on-farm environment rather than in a clean laboratory. Moving sensors on-farm and in-field enables growers to strategically manage grain quality before the product is sold (post-farmgate) (

Figure 1). The most common commercially available sensor that determines grain composition is the benchtop NIR. Growers’ subsample harvested grain and use these systems to determine moisture and protein prior to sale or storage.

Technologies that are currently commercially available that have the potential to objectively measure grain quality for trade purposes and are likely to be adopted within the next five to ten years include NIR, digital RGB imaging, multi- and hyper-spectral RGB and NIR sensors (

Figure 1). These sensors enable rapid and non-destructive approaches to determine grain quality and are used to analyse plant and grain material for research purposes in-season, at-harvest, and post-harvest [

16,

19,

27,

28,

29]. In this review, the focus is on digital imaging and NIR spectral technologies, as these are currently used in research in-lab and, as described, are moving from lab to farm but there are several considerations needed to make this possible. In this review the focus is the commercial and research landscape of current and emerging visible and NIR sensor systems, with consideration of the practicality of applying these technologies on-farm to assess quality traits used to determine market value. Low-cost portable sensors are moving from research, benchtop, laboratory applications to on-farm practical applications where grain quality can be measured objectively in real-time and inform grain management decisions prior to sale post-farm gate.

A critical step in applying sensor technology for determining grain quality is the analysis of the data collected. The application of different analytical techniques is dependent on the types of data generated by different types of sensors. Colour space analysis [

30], for example, is appropriate to use with digital imagery (RGB), while machine learning methods generally require very large data sets and are adept at finding patterns within high-dimensional data sets. As processing speeds increase and computational costs decrease, even more data-intense analytical techniques can be used to help interpret data and in near real-time. To make best use of sensors and the increasingly large amounts of data produced, it in critical to select appropriate software analytical techniques to work hand in hand with the sensor hardware.

This review summarises current sensor technologies that are in the research phase and can potentially be applied on-farm within the next five to ten years, algorithm approaches that can be applied, and the planning, logistics and decision-making processes involved with determining grain quality on-farm to classify market value.

1.1. Application of sensing grain quality in-season prior to harvest

Within dryland cropping systems, proximal and remote sensing technologies are being used to capture and manage temporal and spatial variability that cause variation in crop growth, yield and quality across the landscape [

31,

32]. Remote sensing can operate at multiple scales to assess crop growth and stress including using hand-held instruments at field scale, airborne platforms at the field and farm scales and satellites at scales from field to regional levels (

Figure 1). For example, a crop reflectance index referred to as the Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), measures the difference between near-infrared (vegetation strongly reflects) and red light (vegetation absorbs). This index measures crop canopy cover and can correlate with plant biomass enabling the monitoring of vegetation systems [

33]. In one long-term study which assessed the response of winter wheat to heat stress on the North China Plain, canopy reflectance measured from satellite platforms [

34] was used to assess crop phenology and senescence rate (spatially and temporally), providing insight into climate change impacts on broadscale production potential. Canopy reflectance information using targeted spectral indices from the visible and near infrared spectral regions has also been correlated with plant nitrogen status in wheat [

35] leading to development of indices including the Canopy Content Chlorophyll Index (CCCI) and the Canopy Nitrogen Index (CNI) at the experimental plot scale. Further testing of these indices across different dryland growing environments in Australia and Italy confirmed their utility, with good agreement between these indices and canopy nitrogen concentration (r

2 = 0.97) early in the growing season [

15]. In this example, such canopy-based remotely sensed indices provide growers with a decision support tool to guide in-season nitrogen fertiliser application, enabling spatial management of fertiliser rate across the paddock, thus optimising the match between plant nitrogen demand and application.

More recently, crop canopy reflectance characteristics have also been used to monitor frost damage in wheat grown in southern Australia [

16,

19], where rapid estimation of frost damage to crops on a spatial basis supports the timely management decisions by growers to reduce the economic impact of frost. In these studies, where hyperspectral reflectance and active light fluorescence were assessed, the reflectance indices Photochemical Response Index (PRI), Normalised Difference Red-Edge Index (NDRE), NDVI and the fluorescence-based index FLAV (Near InfraRed Fluorescence excited with Red/InfraRed Fluorescence excited with UV (375 nm) correlated well with frost damage experimentally imposed to field grown wheat at flowering. These principles are now evolving to more widespread application within the grains industry, with service providers now offering seasonal satellite imagery and interpretation in the context of crop performance, spatial variation (topography) and soil characteristics. This data can be useful to inform management of different parts of a paddock or farm (as management zones) for nutritional, abiotic, and biotic disorders to maximise yields and ensure high grain quality.

Much research undertaken on-farm relates monitoring of canopy reflectance to crop growth and yield. However, this review highlights the importance and value of predicting quality of the end-product, i.e., the grain, for growers on-farm. To predict grain-yield, a study that employed hand-held hyperspectral devices assessed variation in frost affected lentil crops and confirmed that frost damage can be effectively detected in-season using remote sensing and that the stress response corresponds to both yield and quality outcomes [

4,

36]. Similarly, use of the active light fluorometer index FLAV in chickpea and the spectral reflectance-based Anthocyanin Release Index 1 in faba bean have shown utility for detection of the disease Ascochyta blight at the leaf-level [

37]. Given the potential for Ascochyta blight, a fungal disease in pulse grains caused by

Ascochyta rabei,to affect grain quality, this offers the opportunity for improved control of diseases through spatial management of foliar fungicides [

37], potentially reducing associated quality downgrades and seed carryover. More broadly, if variation in crop canopy reflectance (NIR) based on environmental stresses could be linked to grain quality, this would allow in-season mapping to predict spatial variation in grain quality, prior to harvest. With this knowledge, the harvesting program could be tactically designed to harvest zones based on predicted yield and limit economic losses to environmental effects on grain quality within the grains industry.

Monitoring of crop canopies using spectral analysis has potential to provide growers with the tools to better manage grain quality. For this technology to be applied on-farm, further research is required to identify remote sensing measures that correlate with grain quality outcomes for key crop species. The logistics of employing such techniques on-farm must also be considered; timeliness of collecting and interpreting spatial data to inform harvest zoning, and the physical infrastructure and logistics to accommodate the various quality grades are two such examples. Developing prediction models for grain quality based on sensor data will inform harvest zones for quality and maximise financial return.

1.2. Data acquisition systems and sample handling at- or post-harvest

In addition to monitoring and managing grain quality prior to harvest, there are opportunities to directly monitor grain quality at various points in the supply chain from harvest through to sale. In this case, sensors could be installed within harvesting or grain handling machinery [

23], in grain storage infrastructure [

38] or in a ‘benchtop’ or laboratory setting similar to grain receival points [

29]. Compared with in-season quality monitoring, assessment of grain quality at harvest or during movement to storage, offers the advantage of avoiding the need for mapping and interpreting quality data prior to harvest, saving an additional operation. It may also allow for identification of quality defects not otherwise evident through spectral analysis of the crop canopy; for example, instances where weeds or other contaminants (e.g., snails) that arise closer to crop maturity.

Monitoring of grain quality at- or post-harvest can also be undertaken spatially, enabling proactive management in future seasons. Commercially available grain protein monitors are one such example [

23,

39] enabling segregation based on grain quality at harvest or during movement into or out of storage, while providing information to inform future decisions relating to nitrogen fertiliser. In addition to segregating grain based on quality grade, monitoring quality at- or post-harvest may enable growers to blend grain of various quality levels in specific proportions prior to entering storage [

39]. This strategy can be used to ‘lift’ low quality grain from one grade to the next, helping to achieve the highest aggregate quality and price for grain produced across a farm business.

In addition to monitoring grain quality at-harvest or during movement into storage, directly monitoring grain quality could also be undertaken during storage. Studies such as [

40] and [

41] have shown that grain quality can change over time. While optimising storage conditions through aeration, temperature control and fumigation can all help to maintain grain quality for longer, monitoring of stored grain

in-situ offers the potential to target marketing decisions based on projected commodity prices and prediction of grain quality over time.

In considering on-farm application of grain quality monitoring systems, it is important to understand accuracy requirements. The ultimate success of quality monitoring is dependent on its ability to correctly classify a known volume of grain into its respective quality grade to trade. The accuracy required will depend on the crop species and the quality grade being targeted. This is further complicated where the quality of a given grain parcel varies across different target traits, e.g., contamination, colour, and size, requiring more comprehensive monitoring systems with multiple algorithms (and perhaps different technologies) to account for the different traits within the grade. Typically, the utility of a monitoring system depends on the accuracy of both the instrument and the sampling process. Analysing a sample that is representative of a given parcel of grain is vital to ensure accuracy of the monitoring system [

42] and the ability to apply in an on-farm situation.

2. Sensor Technologies used in the Agricultural production system

Key sensor technologies employed post-farmgate to objectively measure grain quality include: RGB imagery, NIR spectroscopy, and multispectral spectroscopy. Hyperspectral spectroscopy will become more widely adopted for commercial applications on farm as new cheaper sensors are developed and manufactured. These technologies and grain quality applications are summarised in

Table 1 and their advantages and limitations are outlined below.

2.1. Digital RGB Camera

Digital cameras are one of the most widely used sensors with broad applications ranging from industrial quality control, and robotics, to capturing photographs of scenes and objects. These sensors can provide data-rich information and are used to analyse a wide range of visual traits key classifying grain quality [

60]. Digital (RGB) cameras are typically equipped with light-sensitive Complementary Metal–Oxide–Semiconductor (CMOS) or Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) sensors to acquire coloured images of scenes and objects [

29,

60]. Colour filter arrays (CFAs) arranged in a mosaic pattern on top of the sensor selectively filter RGB light, and the intensity of the light in each colour channel at different spatial points on the sensor is measured and used to compose an RGB image [

60]. RGB cameras are commercially sold as DSLR (Digital Single Lens Reflex), small-scale machine vision cameras, industrial cameras, or as a device component, for example in smartphones. The specific application of a camera depends on the resolution of the captured images, optics, light and colour sensitivity, and frame rate, among a range of other factors. Factors including the signal to noise ratio and size of the sensor, optics, illumination, and processing of the image (e.g., interpolation of pixels), determine the raw image data. The resolution of a static photo is usually expressed in megapixels, i.e., the number of pixels (length × width) in the image.

Digital cameras equipped with CMOS sensors are used for process-control and monitoring automated systems. Their adoption is mostly driven by reduced costs, improved power efficiency of the CMOS chips and advancements in machine vision techniques for the analysis of the captured data. CMOS cameras can operate with both passive (sunlight) and active lighting, be deployed on vehicles or UAVs for remote monitoring, and the relatively small size of the generated data (e.g., compared to in-laboratory hyperspectral imaging) enable images to be processed in real-time.

Computer Vision (CV) is the scientific field in which computational methods are developed to derive meaningful information from camera data (images and videos). Computer vision includes computational methods for object and motion tracking, scene understanding, edge detection, segmentation, colour and texture analysis [

61], object detection, classification, and counting, among some of the applications [

62].

Many indicators of food and plant quality, including ripeness of fruit, symptoms of diseases, nutrient deficiencies, damaged plants, weeds and plant species in crop fields, and others, manifest visually and thus assessed according to visual criteria, these features are suitable targets for detection by RGB cameras [

29,

60,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67]. Throughout the agricultural industry, the assessment of morphological and phenotypic features usually requires visual inspection, a labour-intensive process prone to subjectivity and errors. Digital image analysis can improve methods of grain and plant classification according to objective visual criteria. Applications of RGB imaging in grain quality are outlined in

Table 1.

The advantage to using RGB cameras is that images are readily interpretable because the information captured is how a human perceives the appearance of the grain sample. Regarding the limitations for applying machine vision, these are similar to those encountered in human vision, in that they both operate within the visible range of the light spectrum. Quantifying colour using RGB imaging systems is complex as it can be difficult to correct or calibrate between systems due to differences of the camera optics, sample illumination, consistent presentation of the sample for image capture and different ways images can be processed and compressed for storage. The use of consistent lighting across samples and inclusion of calibration panels within images is critical to robustly quantify grain characteristics. Digital imaging captures the external view of samples, where the internal grain structure and chemical information is not detected in RGB images. Therefore, to analyse sub-surface grain features, other spectroscopic techniques would need to be engaged, including NIR, Raman, NMR, UV, X-ray, fluorescence. Another limitation is the sample orientation, RGB imaging captures a one viewpoint of a sample therefore traits, such as, surface area, volume, length, width, and diameter of samples may not be representative depending on sample presentation. Also, certain complex processing traits have been analysed using image analysis, such as grain milling, the error can be high and the range in laboratory values limited, compromising the accuracy and precision of the technique [

27,

68]

2.2. Stereo cameras

Stereo vision and Structure from Motion (SfM) are two methods used for 3D imaging with conventional digital cameras [

69]. Binocular stereo vision uses images captured from two cameras at different angles and triangulation, to compute the depth of scenes, analogous to the human binocular depth perception. In SfM, a single moving camera is used to obtain multiple images from different locations and angles, and the images are processed to obtain the 3D information. Stereo vision enables the estimation of the volume of objects and their spatial arrangements. Most of the applications of stereo cameras in agriculture are field-based and have been to generate 3-D field maps [

70] for biomass estimation [

71], determine morphological features of wheat crops [

49] and crop status including growth, height, shape, nutrition, and health [

69]. There are limited applications of Sfm for grain quality analysis, these include stereo imaging systems with two viewpoints, which has enabled the prediction of grain length, width, thickness, and crease depth in wheat [

72].

As with the 2D or single imaging RGB systems, similar limitations are found with stereo vision systems: the information collected is within the visible range (RGB), sample colour, differences between imaging systems, sample lighting, internal grain structure and chemical information is not detected, and sample orientation may not be visible. The benefit of using a stereo imaging system is that multiple positions of the sample are captured and therefore the data is not limited to one viewpoint, allowing a more complete view of the sample, thereby reducing the error in estimating traits such as surface area and sample volume.

2.3. Near Infrared Spectroscopy

The near infrared (NIR) region of the electromagnetic spectrum encompasses the 700–2,500 nm wavelength range and covers the overtone and combination bands involving the C–H, O–H, and N–H functional groups, all of which are prevalent in organic molecules [

51,

73]. NIR spectroscopy is widely applied to the analysis of materials in agriculture, biomedicine, pharmaceutics, and petrochemistry. In the agriculture industry, NIR spectroscopy is used for determining the physiochemical properties of forages, grains, and grain products, oilseeds, coffee, fruits and vegetables, meat, and dairy, among many other agricultural products [

51,

73].

The instrumentation used in NIR spectroscopy consists of a light source (typically an incandescent lamp with broadband NIR radiation), a dispersive element (commonly a diffraction grating) to produce monochromatic light at different wavelengths, and a detector which records the intensity of the reflected or transmitted light at each wavelength [

73]. An alternative method of obtaining the same information is with Fourier Transform Near-Infrared (FT-NIR) spectroscopy, where the spectrum is reconstructed from interference patterns produced by a Michelson interferometer (interferogram) within the instrument [

74] . Compared to dispersive NIR, FT-NIR systems can collect spectra at higher spectral resolutions, however, unlike gases, this advantage is not significant in analysis of liquids and solid samples, where the spectral bands are broad (> 2 nm). For whole-grain analysis (e.g., protein and moisture constituency), the predictive performance of both types of instruments (FT and dispersive) is similar, indicating no advantage of either method over the other [

75].

NIR sensor readings are referenced with ‘white’ (reference) and ‘dark’ scans obtained from highly reflective (assumed to be 100% reflective) flat and homogenous materials such as fluoropolymers like Spectralon®, and dark current (no light) signals, respectively. The reference panel provides calibration to reflectance, which is the physical measure of light from the surface of an object and the dark measurement quantifies sensor noise. The most common referencing methods assume a linear response for sample reflectance R, given by , where I is the intensity of the signal measured by the sensor and the dark (noise) from the sensor is removed from the sample and reference. Alternatively, sample reflectance may assume a non-linear relation, in which case the reflectance is typically modelled with a higher order polynomial equation, calibrated using a set of reflectance standards (e.g., Spectralon® doped with graded amounts of carbon black) whose reflectance span the ~0—100% reflective range.

NIR spectroscopy is widely adopted, is relatively affordable ($US5,000-$50,000) depending on the application and spectral sensitivity needed, and available as both desktop and portable low-power instruments. NIR can provide accurate measures of the chemical constituency of a sample, including the w/w% of nitrogen concentration (and thus protein), moisture, carbohydrates, and oils, among other organic compounds. Because the NIR radiation can penetrate a sample it can be used to investigate its chemical composition. Furthermore, in densely packed bulk grain where objects overlap and occlude one another, unlike in image analysis, the NIR device is operable and not sensitive to the orientation and careful arrangement of the individual grains and can be used to measure whole grain sample properties.

Traditional NIR spectroscopy sensors, unlike in digital imaging, captures the average spectrum of a sample of grain packed within a measuring cell. Digital images capture two-dimensional information and within the image features can measure grain size distribution, whereas NIR spectroscopy typically in homogenous samples quantifies an average (of the analysed sample) quantity of all the individual grains within the sensor field of view. Complexities in sample composition, mixing of spectral components (different parts of the grains, shadows, contaminants, etc.), and low concentration of analytes, can limit the accuracy of traits measured with an NIR instrument.

Applications for NIR spectroscopy include rapid determination of oil, protein, starch, and moisture in a range of grains and their products [

51], including forages and food products [

76]. Other applications include identification of wheat varieties and seed health [

50], fungal contamination [

43], and prediction of protein and moisture concentration [

51,

76]. NIR has been widely adopted to measure protein and moisture concentration which is then used to determine the value (grade of the grain) and processing quality of the grain, i.e., baking quality in wheat and malting quality in barley.

2.4. Multispectral Imaging

Multispectral imaging acquires reflectance data at (often narrow) discrete bands (up to about 20) spanning the ultraviolet (UV), visible, and near infrared (NIR) regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. In contrast, RGB colour images only provide data at three (broad wavelength) channels (R, G, and B) within the visible spectrum. Regardless of the modality (RGB, multispectral, or in-lab hyperspectral) the data is organised in three-dimensional numerical arrays (i.e., data cubes) where the first two dimensions (X, and Y) correspond to the spatial information, and the third dimension (λ) stores the spectral information. There are three main methods for the acquisition of data in spectral imaging systems, named after the sequence of data acquisition along each of the X, Y, and λ directions: (i) point-scanning (whiskbroom), (ii) line-scanning (push-broom), and (iii) area scanning methods. Multispectral imaging has similar applications to RGB imaging, however as the spectral bands can extend beyond the visible region, multispectral imagers have been used to identify wheat varieties, detect black point disease or fungal contamination [

50,

54], tracking desiccation of seeds [

52], seed authentication [

53], and identify the histological origin of wheat grain [

55]. Point-scanning involves the acquisition of a complete spectrum at each spatial point (X, Y) and the data is stored in band-interleaved-by-pixel (BIP) format. Because the spectrum at each pixel is acquired one at a time, this system is typically used in microscopy (e.g., atomic force microscopy) where acquisition speed is not a priority (because the object is not moving). In line-scanners, data is recorded line by line (y, λ) as the target sample moves along the X-direction. The data is stored in band-interleaved-by-line (BIL) format. This configuration is typically used in industrial scanners where samples are scanned during their movement on a conveyor under the imaging system. This is also typical when the sensor itself is moving across a stationary target, such as when deployed from an aircraft. In area-scanners, an entire 2D image is acquired at each λ, which results in a band-sequential (BSQ) data format. This method requires a rotating filter wheel or a tuneable filter (e.g., Liquid crystal tenable filter, LCTF, or Acousto-optic tuneable filters, AOTF) to target the wavelengths of interest at each scan and is generally not suitable for moving samples, unless movement is minimal with a high degree of overlap [

73]. Other imaging systems use LEDs of different emission wavelengths (UV—NIR) to sequentially illuminate objects placed in a dark enclosure to capture greyscale images, which are then multiplexed along the λ direction to form the multispectral data. Variations in illumination (due to lighting geometry and setup), sensor sensitivity, imaging method, and environmental conditions (e.g., temperature and humidity) can affect the data quality acquired by spectral imaging systems, hence calibrations of these systems are very crucial and important for their function [

27]. In remote sensing applications, the set of calibrations are often referred to as radiometric calibrations, which additionally account for the effects of altitude, weather, and other atmospheric conditions [

77].

Low frequency NIR wavelengths or UV have been used in multispectral imagers that can penetrate objects to capture information beyond the surface images of standard RGB cameras. Therefore, features ‘invisible’ to RGB imaging can be used to determine chemical composition of samples, albeit with limited accuracy, depending on the number and frequency of the spectral bands. Multispectral systems are limited in their capacity to measure chemical composition of samples effectively because only a limited number of wavebands tend to be utilised to ensure the instrument is low-cost. Hyperspectral imaging and spectroscopy methods are suited for this purpose. Furthermore, multispectral cameras are more expensive than digital RGB cameras.

2.5. Hyperspectral

2.5.1. In-field measurements

In-field hyperspectral sensors collect single point data from the target, usually either in the visible-NIR (350–700 nm) or from visible to mid-IR (350–2500 nm), depending on the type of materials used for the sensors. Because these sensors collect single point data, they average the spectral response across the measured area. In-field hyperspectral sensors are used to quantify crop conditions, for example the impact of biotic and abiotic stresses on grain yield and quality [

4,

19,

36,

37]. Advantages are collection of detailed spectral signatures to quantitatively assess crop/ plant health and function. Disadvantages include the cost of the portable instrumentation (>

$US100,000), the complexity of calibration, removing noisy data due to sky and environmental conditions, collection of appropriate and relevant reference data, and development of robust calibrations that can be applied across a range of weather conditions.

2.5.2. In-laboratory hyperspectral Imaging

Laboratory (in-lab) hyperspectral imaging systems combine the benefits of imaging and spectral systems to simultaneously acquire spectral and spatial information in one system. This can be applied to the quantitative prediction of chemical and physical properties of a specimen as well as their spatial distribution simultaneously. The inner workings of in-lab hyperspectral systems are like multispectral systems, with variants that use dispersive optical elements or LCTF/AOTF to record spectral signals, however unlike multispectral images where up to 20 discrete bands are recorded, a hyperspectral system typically acquires several hundred contiguous wavelength data points at each image pixel. The most common dispersive hyperspectral imaging sensor is the push-broom line scanner [

73].

In-lab hyperspectral imaging has been used extensively for quality evaluation of fruits and vegetables, enabling the detection of contaminants [

78], bruises [

79], rot [

80], and quality attributes including firmness [

81], moisture and soluble solid concentration (SSC) [

82,

83], and chilling damage [

84]. The publication of applications using hyperspectral technologies in agriculture have increased over the past 30 years with over 245 articles published from 2011 to 2020 [

85], and relevant on-farm applications are outlined in

Table 1.

The major limiting factors for the implementation of hyperspectral systems that measures within the NIR spectrum (980-2500nm) is cost (~$US200,000), high dimensionality, and volume of captured data, creating challenges in online real-time systems. It should be noted that hyperspectral imagers that measure the visible region, or short wavelengths are considerably cheaper, and therefore can be applied to specific applications. Hyperspectral systems that capture the whole spectrum are best suited for identification of optimal wavebands and efficient algorithm development, which can be exploited in the development of spectral imaging system with a limited number of wavebands (e.g., multispectral) systems which have the capability to meet the needs of real-time acquisition and processing. However, as noted previously, multispectral systems may not provide the degree of precision as hyperspectral systems.

3. Data Analysis and Modelling

The aim of using sensor technologies is to measure different grain traits rapidly and non-destructively based on specifications set by the needs of industry and grain trade standards. The challenge in the application of sensor technologies is that interpretation of the data can require complex algorithm development. Mathematical models are built to predict the desired trait or grain class, using numerical or categorical descriptors, or to discover patterns and relations in the data. The set of methodologies that ‘learn’ to build models from data (as opposed to being strictly programmed), are broadly referred to as machine learning methods (

Table 2). Machine learning is typically categorized based on the learning type (supervised or unsupervised), and learning models (regression, classification, clustering, dimensionality reduction, target detection).

At their core, machine learning algorithms are tasked with finding solutions to an optimisation problem. One of the simplest examples is ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, where parameters of a linear function are found that minimise the sum of the squares of the residuals (i.e., differences between observed variables and those predicted). More complex tasks, which involve high dimensional data and nonlinearities, require more complex algorithms, yet the basic principles (i.e., minimisation of prediction error) remain the same.

This review provides a brief descriptions of existing machine learning methods used for data analysis and modelling. Many of these techniques can be applied to analysis of NIR spectral, digital RGB image, and multi/hyper-spectral imaging data and be used to perform both regression and classification of the trait of interest. Image data generally involves an additional set of unique methods using computer vision, a subset of machine learning which deals with vision specific tasks that includes image recognition, segmentation, target tracking, and motion estimation, among others.

3.1. Regression

The most basic form of regression is simple linear regression, in which a linear function is fitted to a predictor variable and a response variable. The linear equation consists of two unknown parameters (slope and intercept) which are found by minimizing the root-mean square (RMS) error of the resultant fit. RMS error is used in OLS, although alternatives such as mean absolute error (MAE) are sometimes used. The extension of simple linear regression to multiple predictor variables is known as Multiple Linear Regression (MLR). Another term, multivariate (or general) linear regression, refers to cases where there are both multiple predictors and multiple response variables. MLR is suited to modelling linear relationships, with the use of one or more independent variables. A typical challenge in using regression to model spectral data is the high degree of multicollinearity (i.e., correlation between predictor variables) in the data, which is usually remedied by using an independent subset of the data (e.g., Principal components) as predictor variables in the model. Applications of MLR in Agriculture include detection of fusarium head blight in wheat kernels [

54], determination of quality attributes of strawberry using hyperspectral imaging [

82], and assessment of lentil size traits [

29].

3.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Principal component analysis (PCA) is one of the most widely used dimensionality reduction algorithms, typically used to represent high-dimensional correlated data. In general, a dataset may contain measurements of features (e.g., colour, size, shape, etc.) from many samples. Principal components (PCs) refer to the axes of a new coordinate system along which the measurements are maximally correlated. The first PC accounts for the highest variance in the data, followed by the second, third, fourth, etc. Effectively, PCA allows high dimensional data to be represented in fewer dimensions. PCA is often used to reduce highly correlated data to a small subset of independent variables which can be used in other analysis techniques, such as regression. An extension to PCA known as principal component regression (PCR) uses the PCs of the explanatory variables to perform standard regression to describe a dependent variable. Application of PCA include the study of the relation between dough properties and baking quality [

86], characterization of desiccation of wheat kernels [

52], and as a dimensionality reduction technique in many other applications [

87].

3.3. Partial Least Squares (PLS)

Partial least squares or projection to latent structures (PLS) is a technique widely used in chemometrics (

Table 2). The principles of PLS are similar to PCR, i.e., the independent variables are first projected to a new space to reduce the dimensionality of the data and to infer a set of latent variables, which are then used to perform standard regression or classification. The technique is suitable for modelling highly collinear data such as NIR spectra with broad chemical signatures that contain many redundancies. PLS is broadly used in chemometric analysis [

51] for measuring key traits such as protein and moisture in grain [

1,

28,

88,

89].

3.4. Linear discriminant analysis (LDA)

Linear discriminant analysis is one of the standard methods used to classify linearly separable data into two or more categories [

66]. The goal of LDA is to find a linear combination of predictors (i.e., projection to new feature space) that separates two or more classes in the data. The new feature space is obtained by finding a projection that maximizes the distance between the inter-class data, while minimizing the intra-class data [

90]. Application of LDA include use in differentiation of wheat classes with hyperspectral imaging [

91], classification of defective vs. non-defective field pea using image features [

10], and detection of fungal infection in pulses [

92].

3.5. Support Vector Machine (SVM)

Support vector machines (SVMs) are methods used to classify data into two classes (binary classification). An SVM classifies data by finding the best hyperplane that separates all data points of one class from those of the other class. The best hyperplane in the case of SVMs is the one that creates the largest margin between the two classes. For multi-class problems, several binary problems must be applied. Other versions of SVMs include support vector regression (SVR), and least-squares support-vector machines (LS-SVMs).

SVMs are one of the most successful machine learning algorithms, and have been widely used in industry and science, often providing results that are better than competing methods. Applications to agricultural sensor data modelling include use in analysis of chalkiness in rice kernels [

93], classification of contaminants in wheat [

94], and quality grading of soybean [

95].

3.6. Decision Trees Learning

In decision trees or classification trees the objective is to construct a flowchart for making decisions based on criteria related to a desired outcome. The decision trees are often constructed by experts with knowledge of the decision-making process. Decision tree learning (DTL) provides an algorithmic technique for constructing the tree based on data, for use in creation of predictive models for classification or regression. An extension to decision trees is known as random forests, where many decision trees are constructed to provide a more robust framework and avoid the common overfitting pitfalls experienced in DTL. Overfitting typically occurs when the model has too many parameters compared to the number of predictors, which manifests as good fit to the training data, and poor prediction accuracy on new data. Overfitting is best managed using model validations, as discussed in

Section 3.8. Applications of decision trees include discrimination of wheat varieties using image analysis [

96], and classification of corn crop treatments from remote hyperspectral data [

97].

3.7. Neural networks and deep learning

Artificial neural networks (ANN) are a class of computation structures inspired by the functionality of the human brain. Basic units referred to as artificial neurons receive weighted inputs from other neurons and generate an output. The weight of a neural connection is typically normalized to the range 0 (i.e., no connection) and 1. Many neurons organized in networks enable complex information processing that include pattern recognition, feature extraction, and learning. Training ANNs involves the adjustment of the weights of the network, until the network output matches the desired output, given by a set of labelled training data (supervised learning). Many iterative optimization algorithms such as stochastic gradient descent (SGD) and back-propagation can be used to train ANNs.

Deep learning (DL) typically refers to ANNs with many layers of neurons. The different layers enable networks to learn complex data representations at multiple levels of abstraction. A common DL architecture is the convolution neural network (CNN), inspired by the neural connectivity in the visual system of mammals where connections are locally constrained. CNNs are particularly suited to image related tasks. Other DL architectures include fully connected networks (FCN), recurrent neural networks (RNN), generative adversarial networks (GANs), and auto-encoder networks. Applications of ANNs include modelling chemical constituency of cereals and pulses [

28], classification of beans using images [

98], prediction of wheat yield [

21], among many others [

99].

3.8. Validation

One of the most common strategies used to assist in model selection and reduce overfitting is the use of cross-validation. During model development, random portions of the data are used to build the model, while the withheld portion is used to evaluate the performance of the model. A collection of common statistical metrics used to evaluate regression and classification models is listed in

Table 3.

There are many ways in which cross-validation can be performed, depending on what subset of the data is used for building the model (training) vs. validation. Popular strategies include k-fold cross-validation, repeated random subsampling validation, and leave-one-out cross validation methods.

Independent validation is essential when assessing the feasibility of an application to test the accuracy and reliability of the algorithm(s), procedures, and equipment. It is particularly important to determine if the calibration set is well constructed and can measure all variations in the desired trait. Ideally the validation samples will be sourced from the new harvest, potentially a range of sites, covering all possible varieties of crops that will be assessed [

100]. Independent validations and continuous monitoring are necessary when ensuring new sensor technologies are applied successfully, particularly for different growing locations, environmental conditions, transporting conditions and storage conditions such as those found on-farm.

4. Sensor technologies applied in-line within agricultural systems

Real-time measurements of grain quality have been implemented in a range of agricultural processing industries on production lines to segregate between a market quality and identify out of specification (or defect/contamination) product [

26]. The advantage of such technologies is that they are non-destructive and can be applied with speed and accuracy, and do not tend to disrupt processing the commodity. Segregation technologies can be applied at multiple points within the processing chain, for example measuring the bulk commodity before, during, and after processing, and have been applied in many food processing applications.

Table 4 describes relevant applications for grains in food and agriculture. Various applications have been employed for a range of grains and seed, and industries to ensure a specific quality of end-product is achieved throughout processing (

Table 4).

Full spectral or multispectral sensors have been successfully engineered within grain processing lines where the product is measured in-line, such as grain passing by a camera on a conveyor belt [

29], or the grain is subsampled as it is harvested and measured in a sampling device with an NIR [

39]. Once analysed, the grain can be classified or quantified to inform decisions, such as to reject or modify the process when an out of specification limit is detected. For on-farm quality segregation, sensor technologies can be applied at-harvest as the grain is transferred into chaser bins or trucks (classifying the whole of load), or potentially the grain can be ‘actively’ segregated in-line using a diverting system as it is being loaded onto the truck. An example of ‘active’ segregating using a diverting system based on a binary decision is where high protein wheat is separated from the low protein wheat into two bins [

26]. It should be noted that cost of the installation, measurements representative of the batch (sampling), accuracy of the algorithm and the speed of the decision-making process are major considerations in any in-line application.

Sensor technologies have been applied to coarse material, such as grains, with a range of accuracies (

Table 4). The accuracies are dependent on many factors, some of these include the sensor-type, sample presentation when the measurement is taken, and the type of parameter measured (protein, moisture, grain size). In addition, if segregating the product into two streams, poor and good quality, then other considerations include processing speed and delay between the measurement and sorting device.

Successful applications (with an R

2 > 0.88 and classification models >77%) have been developed in the use of image analysis and near infrared technologies to classify and quantify grain based on colour, shape, size, moisture, protein, broken, damaged and contaminated course samples (

Table 3). Key quality traits of major importance to the agricultural industry include protein, moisture, grain size, discoloured or damaged grain, and contaminates (

Table 4) could be objectively assessed with portable sensors on-farm. These traits could be incorporated into a decision process that assists growers and traders to manage the harvested grain based on quality traits to maximise profitability at time of sale. The adoption of such technologies will be dependent on cost, complexity of the application, ease of use and likelihood of disruption or breakdown during use (

Table 5).

5. Considerations for Adoption

5.1. On-Farm Segregation and Storage

Segregation of grain, based on quality-traits can be implemented pre-harvest through the application of within field zoning of different quality, during harvest using on-header sensing segregation, or post-harvest storage and out-loading. Growers can decide to implement these strategies individually or in combination. How a grower chooses to implement segregation will, to a large part, depend on the economics and logistics involved.

Cropping enterprises have historically used on-farm storage as a strategy to minimise economic risk and mitigate the impacts of variable market conditions. Grain storage provides options to growers at harvest by broadening the harvest window while also preventing the loss of grain attributed to extreme weather events, crop shedding and/or lodging, as well as reducing the time trucks are unavailable due to unloading [

112]. In addition, on-farm storage allows growers to temporarily hold grain until desired market prices can be received. In these instances, growers often blend grain of differing quality to reduce downgrading and segregate grain based on quality specifications [

112].

While the economic benefits of segregating, blending, and storing grain are evident, the cost of capital infrastructure requirements need to be considered. One major issue associated with on-farm storage, particularly vertical systems, is the difficulty in determining the cost-benefit of increasing storage capacity, where fluctuating annual yields will often mean an under-utilisation of space or a requirement to store grain in temporary bunkers, use of grain bags or the decision to send directly to receival [

112]. An added level of complexity with segregation is attempting to pre-determine the storage requirements for the potential grain yield and grade. Increasing the number of segregated or blended groups, a greater number of smaller storage vessels will be needed to decrease the size of each management unit and increase the opportunity to benefit from segregation. In addition to efficiencies gained by a general increase in on-farm storage, smaller and greater numbers of vertical storage systems will decrease the amount of grain requiring cleaning and increase the control growers will have to sell, feed out or store grain for future seeding.

5.2. Data and Interfaces

Developments in precision agriculture technologies have seen an increase in the intensity of information and data transfer required between sensors, computers, and users. In recent years, sensor capability, advanced computing, robotics, automation, wireless technology, GIS (Geographical Information Systems) and DBMS (Database Management Systems) have contributed to the complexity and rate of data communication [

113,

114]. While many efficiencies have been gained (i.e., Variable Rate Technology), the production of large data sets for growers and advisors to collect, decipher and utilise has often discouraged adoption. [

115] identifies that this ‘data overload’ must be overcome by the development of data segregation tools, expert systems, and decision support capability. This ‘data workflow’ needs to be well designed such that user interaction is clear, unencumbered, and informative. This will require well-designed integration of hardware, software, and decision support tools irrespective of how the grower chooses to implement segregation.

Integration of data systems is an issue continually raised in the agricultural technology sector. Surveyed growers, e.g., [

114], have expressed a preference for interface systems that are either independent but intuitive to operate or preferably, integrate into current systems and monitors. However, despite the generation of standardised data protocols for farm technology, i.e., ADIS - Agricultural Data Interchange Standard and CANbus [

113] many manufacturers of agricultural equipment have restricted data to proprietary formats that limits their interoperability. Adoption of a segregation system would likely be influenced by the ability of the technology to integrate with existing systems both for ease of operation and centralising farm data. Advancements in telecommunication networks, such as Internet of Things (IoT) and wireless networks, has significantly increased the opportunities for connectivity and integration of on-farm sensors [

116]. Despite this, there remains a need for new interfaces to be as intuitive, reliable, and available as possible to promote adoption and satisfy the needs of growers [

117]. Finally, the intellectual property (IP) around who holds and has access to data and data governance is an issue that has become increasingly important in the use of these data-intensive technologies and there are national and international regulations that are being developed [

118].

5.3. Calibration and Technical Support

A common feature of sensor-based tools is the requirement for regular calibration and correction. Most sensors, such as multispectral imaging systems, require frequent radiometric calibrations and corrections which are critical to obtaining data that can be compared over multiple time periods [

119] by accounting for changes in environmental conditions such as light intensity and atmospheric and surface conditions [

120]. A sensor-based system, whether pre-, at or post-harvest, will inherently require calibration and correction to account for changes in crop species, variety, location, time, and additional variation attributable to the sensor type and measurement parameters. For growers, the perceived lack of benefit of adding this level of complexity to a system, is often what drives growers to favour other emerging technologies (i.e., disease/herbicide tolerant varieties) and limit sensor adoption [

121]. A study by [

122] summarised over 30 grower surveys, indicated that in addition to calibration and correction; troubleshooting, training and support for new farm technology also determined a grower’s PEA ‘Perceived Ease of Use’, and that PEA was positively related to adoption. Thus, along with the development of robust hardware, software, interfaces and data workflows, competent technical support is required for these technologies to be adopted by growers.

6. Gaps, Challenges, and Benefits

Current systems that classify grain quality to determine graded segregations for trade require a range of standardised methodologies and instrumentation (including benchtop-NIR, a range of nested sieves, balances, chondrometer, visual grain inspection, etc.). Other considerations for the grower when classifying grain quality on-farm includes training operators each season, ensuring the sensor windows are clean and free of dust, the influence of temperatures on instrumentation, adequate storage of instrumentation, ways of recording data and relating the information back to each load, chaser bin or storage facility, and ensuring that the instrumentation is kept clean (free of mice damage and dust, etc). Clearly, data workflows that are as automated as possible would ease the ability of growers to adopt sensor technology. The benefits and challenges for applying sensors that can classify grain quality traits on-farm are listed in

Table 6.

Developing sensor technology systems designed to measure a range of objective and subjective traits, such as grain size and visually assessed traits, would be advantageous to growers particularly if the devices incorporated portable Wi-Fi or Lorawan and were permanently installed on grain-moving systems (i.e., harvesters, augers, belt movers). By having a system that simultaneously measures multiple traits improves efficiencies and synergies as one system would replace many tests (sieves, balances, NIR, chondrometer, visual inspection). This includes the value in synergies of having fewer instruments to do more on-farm and the associated benefits to growers.

The ability to actively manage grain throughout production, storage, and transport, requires the development of systems that can maximise growers returns. As grain market classes are defined by specific varieties and grain traits important for end-users, the development of applications (sensors and algorithms) on-farm will enable growers to objectively quantify the value of their crop. Key quality traits for growers include protein and moisture percentage, grain size and defects such as weather damaged, stained grain, and contamination. Currently there are instruments with the ability to test both small parcels of grain (~200g), large scale (in-line harvester or auger, representing ~100-500 tonnes), and portable sensors that measure crop canopy for crop growth and yield components. Through the development of grain-quality applications to quantify market class, growers will be able to segregate grain on-farm to potentially achieve higher aggregate prices and capture premiums for higher grades and minimise downgrades.

The use of on-farm storage is increasing each year and is altering harvest logistics. With the addition of on-farm storage to a farming enterprise, growers can delay strategic decisions for post-harvest delivery to grain agents. Delaying delivery minimises exposure to price fluctuations as traditionally growers would off-load the grain directly after harvest, when grain supplies are high and therefore driving grain prices down. Storage facilities can also allow growers to focus on harvesting their crop and decrease time taken to off-load and transport grain during peak times. However, there is risk associated with on-farm storage as sub-optimal storage practices can result in spoilage of grain and a loss in quality. Grain storage risks could be potentially minimised if sensor technologies were used to monitor grain quality variation over time.

Grain is increasingly being utilised by non-traditional markets, for example plant-based proteins, and there is a need to identify the quality requirements so that processing needs are met for these emerging and expanding opportunities. The demand for protein-rich meat alternatives is increasing, where the plant-based protein industry is estimated to reach a value of

$US 17.8 billion dollars globally by 2027 [

123]. Therefore, future considerations for the grain sector include a range of sensor tools that identify the quality specifications needed to produce a consistent high-value product. Developing sensor technologies that can capture these opportunities will ensure that the grains industry sector remains competitive as these markets emerge.

Another opportunity for the application of sensor on-farm is to meet the increasing demand by consumers to know more about the provenance of food; its composition, quality and whether it adheres to ethical considerations. Therefore, growers will require tools that can link crop data and trace the source of production, identify quality components of the product, and other food system characteristics. These tools and data have to potential to; inform systems that minimise waste, improve operational efficiencies and processing, assist in demand forecasting, manage compliance and quality issues detected along the supply chain, and evaluate the production system from harvesting to off-loading post-farm gate. The development of innovative e-tools that accurately record on-farm analytics, link source (seed and location), authenticity of quality (variety, composition), storage and handling conditions can ultimately be fed into the supply chain and utilised by growers, grain agents, food processors and consumers who can determine product value, build product confidence, and demonstrate evidence of quality product from paddock to plate.

In the future, sensor technologies integrated at different stages of the grain-value chain will offer practical solutions that enable growers and the grains sector to identify, manage and segregate grain to maximise product quality and value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C. Walker, J. Panozzo, J. Nuttall; writing—original draft preparation, C. Walker, S. Assadzadeh, A. Wallace, A. Delahunty, J. Nuttall, A. Clancy, G. Fitzgerald, J. Panozzo; writing—review and editing, C. Walker, S. Assadzadeh, A. Wallace, A. Delahunty, J. Nuttall, G. Fitzgerald, J. Panozzo, L.McDonald; visualization, C. Walker; supervision, C. Walker, J. Panozzo, J. Nuttall, G. Fitzgerald; project administration, C. Walker.; funding acquisition, J. Panozzo, J. Nuttall All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded through the Victorian Grains Innovation Partnership, a collaboration between Agriculture Victoria (Ag Vic) and the Australian Grains Research Development Corporation (GRDC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Panozzo, J.F.; Walker, C.K.; Maharjan, P.; Partington, D.L.; Korte, C.J. Elevated CO2 affects plant nitrogen and water-soluble carbohydrates but not in vitro metabolisable energy. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2019, 205, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.T.; McCallum, J.D.; Long, D.S. A Web-Based Calculator for Estimating the Profit Potential of Grain Segregation by Protein Concentration. Agronomy Journal 2013, 105, 721–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghetti, V.L.; Pohndorf, R.S.; Biduski, B.; Zavareze, E.d.R.; Gutkoski, L.C.; Elias, M.C. Wheat grain storage at moisture milling: Control of protein quality and bakery performance. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2019, 43, e13974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahunty, A.; Perry, E.; Wallace, A.; Nuttall, J. Frost response in lentil. In Part 1. Measuring the impact on yield and quality. In Proceedings of the 19th Australian Agronomy Conference, Wagga Wagga, NSW; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, C.; Armstrong, R.; Panozzo, J.; Partington, D.; Fitzgerald, G. Can nitrogen fertiliser maintain wheat (Triticum aestivum) grain protein concentration in an elevated CO2 environment? Soil Research 2017, 55, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, M.; Hurburgh, C.R. Framework for implementing traceability system in the bulk grain supply chain. Journal of Food Engineering 2009, 95, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgault, M.; Löw, M.; Tausz-Posch, S.; Nuttall, J.G.; Delahunty, A.J.; Brand, J.; Panozzo, J.F.; McDonald, L.; O’Leary, G.J.; Armstrong, R.D.; et al. Effect of a Heat Wave on Lentil Grown under Free-Air CO2 Enrichment (FACE) in a Semi-Arid Environment. Crop Science 2018, 58, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.S.; Assadzadeh, S.; Panozzo, J.F. Images, features, or feature distributions? A comparison of inputs for training convolutional neural networks to classify lentil and field pea milling fractions. Biosystems Engineering 2021, 208, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assadzadeh, S.; Walker, C.K.; McDonald, L.S.; Panozzo, J.F. Prediction of milling yield in wheat with the use of spectral, colour, shape, and morphological features. Biosystems Engineering 2022, 214, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.S.; Panozzo, J.F.; Salisbury, P.A.; Ford, R. Discriminant Analysis of Defective and Non-Defective Field Pea (Pisum sativum L.) into Broad Market Grades Based on Digital Image Features. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0155523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, N.; Whitworth, M.; Fisk, I. Application of calibrations to hyperspectral images of food grains: example for wheat falling number. Journal of Spectral Imaging 2017, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttall, J.G.; O'Leary, G.J.; Panozzo, J.F.; Walker, C.K.; Barlow, K.M.; Fitzgerald, G.J. Models of grain quality in wheat—A review. Field Crops Research 2017, 202, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, O.S.; Torrion, J.A.; Liang, X.; Shafian, S.; Yang, R.; Belmont, K.M.; McClintick-Chess, J.R. Grain yield, quality, and spectral characteristics of wheat grown under varied nitrogen and irrigation. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment 2020, 3, e20104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, D.; Fitzgerald, G.J.; Belford, R.; Christensen, L.K. Detection of nitrogen deficiency in wheat from spectral reflectance indices and basic crop eco-physiological concepts. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 2006, 57, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarano, D.; Fitzgerald, G.; Basso, B.; O'Leary, G.; Chen, D.; Grace, P.; Fiorentino, C. Use of the Canopy Chlorophyl Content Index (CCCI) for Remote Estimation of Wheat Nitrogen Content in Rainfed Environments. Agronomy Journal 2011, 103, 1597–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttall, J.G.; Perry, E.M.; Delahunty, A.J.; O'Leary, G.J.; Barlow, K.M.; Wallace, A.J. Frost response in wheat and early detection using proximal sensors. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 2019, 205, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behmann, J.; Mahlein, A.-K.; Rumpf, T.; Römer, C.; Plümer, L. A review of advanced machine learning methods for the detection of biotic stress in precision crop protection. Precision Agriculture 2015, 16, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, B.; Fiorentino, C.; Cammarano, D.; Cafiero, G.; Dardanelli, J. Analysis of rainfall distribution on spatial and temporal patterns of wheat yield in Mediterranean environment. European Journal of Agronomy 2012, 41, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.M.; Nuttall, J.G.; Wallace, A.J.; Fitzgerald, G.J. In-field methods for rapid detection of frost damage in Australian dryland wheat during the reproductive and grain-filling phase. Crop and Pasture Science 2017, 68, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEntee, P.; Bennett, S.; Belford, R.; Harper, J.; Trotter, M. Mapping the stability of spatial production in integrated crop and pasture systems: towards zonal management that accounts for both yield and livestock-landscape interactions. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Precision Agriculture, St. Louis, Missouri, USA; 2016; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pantazi, X.E.; Moshou, D.; Oberti, R.; West, J.; Mouazen, A.M.; Bochtis, D. Detection of biotic and abiotic stresses in crops by using hierarchical self organizing classifiers. Precision Agriculture 2017, 18, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skerritt, J.H.; Adams, M.L.; Cook, S.E.; Naglis, G. Within-field variation in wheat quality: implications for precision agricultural management. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 2002, 53, 1229–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, B.M.; Taylor, J.A.; Hassall, J.A. Site-specific variation in wheat grain protein concentration and wheat grain yield measured on an Australian farm using harvester-mounted on-the-go sensors. Crop and Pasture Science 2009, 60, 808–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cillis, D.; Pezzuolo, A.; Gasparini, F.; Marinello, F.; Sartori, L. Differential harvesting strategy: technical and economic feasibility. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Trends in Agricultural Engineering, Prague, Czech Republic, 2016, 2016., 7-9 September.

- Tozer, P.R.; Isbister, B.J. Is it economically feasible to harvest by management zone? Precision Agriculture 2007, 8, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.S.; McCallum, J.D.; Scharf, P.A. Optical-Mechanical System for On-Combine Segregation of Wheat by Grain Protein Concentration. Agronomy Journal 2013, 105, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMasry, G.; Mandour, N.; Al-Rejaie, S.; Belin, E.; Rousseau, D. Recent Applications of Multispectral Imaging in Seed Phenotyping and Quality Monitoring-An Overview. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assadzadeh, S.; Walker, C.; McDonald, L.; Maharjan, P.; Panozzo, J. Multi-task deep learning of near infrared spectra for improved grain quality trait predictions. Journal of Near Infrared Spectroscopy 2020, 28, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMasurier, L.S.; Panozzo, J.F.; Walker, C.K. A digital image analysis method for assessment of lentil size traits. Journal of Food Engineering 2014, 128, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, K.; Mery, D.; Pedreschi, F.; León, J. Color measurement in L*a*b* units from RGB digital images. Food Research International 2006, 39, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, J.L.; Gitelson, A.A.; Schepers, J.S.; Walthall, C.L. Application of Spectral Remote Sensing for Agronomic Decisions. Agronomy Journal 2008, 100, S-117–S-131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R. Remote Sensing of Biotic and Abiotic Plant Stress. Annual Review of Phytopathology 1986, 24, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.; Haas, R.; JA, S.; DW, D. Monitoring vegetation systems in the Great Plains with ETRS. In Proceedings of the 3rd ETRS Symposium, NASA SP353, Washington, DC, 1974.

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tao, F.; Palosuo, T.; Rötter, R.P. Impacts of heat stress on leaf area index and growth duration of winter wheat in the North China Plain. Field Crops Research 2018, 222, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, G.; Rodriguez, D.; O’Leary, G. Measuring and predicting canopy nitrogen nutrition in wheat using a spectral index—The canopy chlorophyll content index (CCCI). Field Crops Research 2010, 116, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E.; Delahunty, A.; Nuttall, J.; Clancy, A.; Wallace, A. Frost response in lentil. In Part 2. Detecting early frost damage using proximal sensing. In Proceedings of the 19th Australian Agronomy Conference, Wagga Wagga, NSW; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, A.; Nuttall, J.; Perry, E.; Brand, J.; Henry, F. Proximal sensors to detect fungal disease in chickpea and faba bean. In Proceedings of the "Doing More with Less", Proceedings of the 18th Australian Agronomy Conference 2017, Ballarat, Victoria, 24-28 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, C.B.; Fielke, J.M. Recent developments in stored grain sensors, monitoring and management technology. IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Magazine 2017, 20, 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, P. Finding the sweet spot in nitrogen fertilization by measuring protein with an on combine NIR analyser. In Proceedings of the 69th Australasian Grain Science Conference, Melbourne, 2019, 26th-29th August; pp. 106–108.

- Cassells, J.A.; Reuss, R.; Osborne, B.G.; Wesley, I.J. Near Infrared Spectroscopic Studies of Changes in Stored Grain. Journal of Near Infrared Spectroscopy 2007, 15, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gras, P.; Kaur, S.; Lewis, D.; O’Riordan, B.; Suter, D.; Thomson, W. How and why to keep grain quality constant. In Proceedings of the Stored Grain in Australia 2000: Proceedings of the 2nd Australian Postharvest Technical Conference, Adelaide, South Australia, 2000; pp. 195–198.

- Wrigley, C.W. Potential methodologies and strategies for the rapid assessment of feed-grain quality. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 1999, 50, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, T.C.; Maghirang, E.; Dowell, F. A Multispectral Sorting Device for Wheat Kernels. American Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology 2013, 2, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragesser, S. Use of color image analyzers for quantifying grain quality traits. 1998.

- Jones, M.A.; Foster, D.J.; Rimathe, D.M. Method and apparatus for analyzing quality traits of grain or seed. 2004.

- Walker, C.K.; Panozzo, J.; Ford, R.; Moody, D. Measuring grain plumpness in barley using image analysis. In Proceedings of the The proceedings of the 14th Australian Barley Technical Symposium, Sunshine Coast; 2009; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, C.; Ford, R.; Muñoz-Amatriaín, M.; Panozzo, J. The detection of QTLs associated with endosperm hardness, grain density, malting quality and plant development traits in barley using rapid phenotyping tools. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2013, 126, 2533–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-S.; Lee, D.-H.; Kim, Y.-J.; Kim, T.; Lee, W.-S.; Choi, C.-H. Stereo-vision-based crop height estimation for agricultural robots. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2021, 181, 105937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandrifosse, S.; Bouvry, A.; Leemans, V.; Dumont, B.; Mercatoris, B. Imaging Wheat Canopy Through Stereo Vision: Overcoming the Challenges of the Laboratory to Field Transition for Morphological Features Extraction. Frontiers in plant science 2020, 11, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrešak, M.; Halkjaer Olesen, M.; Gislum, R.; Bavec, F.; Ravn Jørgensen, J. The Use of Image-Spectroscopy Technology as a Diagnostic Method for Seed Health Testing and Variety Identification. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0152011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.C.; Norris, K. Near-infrared technology in the agricultural and food industries, 2nd ed; Am. Assoc. Cereal Chem.: St. Paul, MN, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jaillais, B.; Perrin, E.; Mangavel, C.; Bertrand, D. Characterization of the desiccation of wheat kernels by multivariate imaging. Planta 2011, 233, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, T.; Nixon, G.; Bushell, C.; Waltho, A.; Alroichdi, A.; Burns, M. Feasibility Study for Applying Spectral Imaging for Wheat Grain Authenticity Testing in Pasta. Food and Nutrition Sciences 2016, 7, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaillais, B.; Roumet, P.; Pinson-Gadais, L.; Bertrand, D. Detection of Fusarium head blight contamination in wheat kernels by multivariate imaging. Food Control 2015, 54, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaillais, B.; Bertrand, D.; Abecassis, J. Identification of the histological origin of durum wheat milling products by multispectral imaging and chemometrics. Journal of Cereal Science 2012, 55, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M.A.; Hatcher, D.W.; Symons, S.J. 17 - Development of multispectral imaging systems for quality evaluation of cereal grains and grain products. In Computer Vision Technology in the Food and Beverage Industries, Sun, D.-W., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: 2012; pp. 451–482.

- Caporaso, N.; Whitworth, M.B.; Fisk, I.D. Protein content prediction in single wheat kernels using hyperspectral imaging. Food Chemistry 2018, 240, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGoverin, C.M.; Engelbrecht, P.; Geladi, P.; Manley, M. Characterisation of non-viable whole barley, wheat and sorghum grains using near-infrared hyperspectral data and chemometrics. Anal Bioanal Chem 2011, 401, 2283–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Li, W.; Du, C.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Sun, Z.; Yang, L.; Yu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z. Predicting micronutrients of wheat using hyperspectral imaging. Food Chemistry 2021, 343, 128473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vithu, P.; Moses, J.A. Machine vision system for food grain quality evaluation: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2016, 56, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]