1. Introduction

Surgeons are increasingly faced with an ageing and frail patient population, leading to challenging risk-benefit discussions in emergency case selection. Frailty may be defined as “a clinically recognisable state of increased vulnerability resulting from ageing-associated decline in reserve and function across multiple systems, resulting in an impaired ability to cope with acute physiological stress” [

1]. Frailty in surgery represents a growing area of interest within clinical practice and research. A significant absence of biomarkers to stratify outcomes of patients undergoing emergency laparotomy exists.

Emergency laparotomy is a highly invasive surgical approach mostly reserved for cases of acute clinical instability or failed minimally invasive management. The pressurised environment, strained hospital resources in combination with an acutely unwell surgical candidate, makes emergency laparotomy a high-risk decision that itself may enhance morbidity and mortality. Consequently, emergency laparotomy may be associated with a prolonged and complicated recovery post-operatively, as well as risk of adverse outcomes; the likelihood of such prospects is increased in frail patients due to their reduced physiological reserve [

2,

3]. Case selection for emergency laparotomy therefore presents a clinical challenge. It is imperative that this at-risk cohort are identified in a timely manner in the acute setting to allow for effective, individualised counselling of the risks and benefits of surgery prior to invasive investigation and management.

At present, patients in the United Kingdom undergo frailty assessment and risk stratification prior to emergency laparotomy using the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) and National Emergency Laparotomy Audit (NELA) risk of morbidity and mortality respectively. These clinical composite scoring systems utilise descriptive parameters such as baseline functional status and co-morbidities to generate a numerical output of risk expressed as a percentage [

4,

5,

6]. These techniques require a comprehensive clinical history which may not be available in the emergency setting and are subjective in nature, risking the under- or over-estimation of morbidity and mortality in certain patient groups [

7].

Inflammageing is a novel concept that describes a persistent state of chronic inflammation, independent of acute illness or injury, that is associated with physiological ageing and frailty [

8]. Existing blood-based biomarkers of inflammation, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), provide rapidly accessible and cost-effective methods of detecting inflammation. The diagnostic and surveillance utility of serological inflammatory markers are widely accepted within modern-day clinical practice. However, their association and clinical significance in asymptomatic, low-grade inflammation is less well established. Inflammageing patients have previously demonstrated poorer outcomes following acute illness with sepsis and cardiovascular disease [

8,

9,

10]; these findings may correlate with an adverse outcome in the post-operative period following emergency laparotomy given its significant physiological burden. Detection of clinical frailty using inflammageing biomarkers has the potential to overcome the raised limitations of clinical composite scoring systems by applying quantitative objective diagnostic criteria utilising readily available serological data.

This retrospective observational study aimed to identify a cohort of inflammageing patients undergoing emergency laparotomy and compare their post-operative outcomes with a non-inflammageing group.

2. Materials and Methods

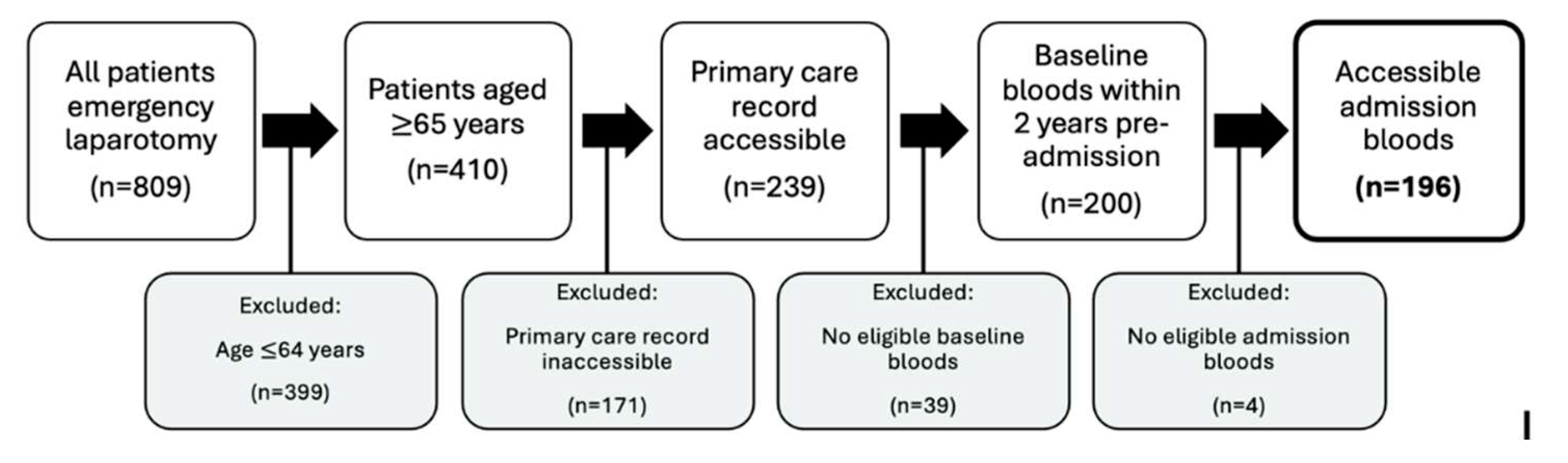

Potential study participants were identified using the NELA database. Inclusion-exclusion criteria were defined in order to capture the relevant patient cohort. The inclusion criteria identified patients aged over 65 years old, undergoing emergency laparotomy within Liverpool University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust between the 1

st April 2017 and 1

st April 2022. The exclusion criteria identified patients aged under 65 years old, those without accessible clinical records and those without eligible serological datapoints. Participant enrolment and flow throughout the study has been summarised in

Figure 1.

Participant demographic data were collected using the NELA database; parameters of interest included patient age, biological sex, past medical and surgical history, regular medications, clinical features and diagnosis.

Biomarker data were sought at two timepoints: (i) baseline serology was defined as routine monitoring blood tests conducted in primary care up to two years prior to admission, excluding datapoints within two weeks of admission; (ii) admission serology was defined as the first-ordered blood tests on arrival in hospital during the index admission. The captured serological inflammatory marker parameters included CRP, ESR, total white cell count (WCC), neutrophil count (NC) and lymphocyte count (LC). Patient clinical records were scrutinised, and data were collected contemporaneously. Baseline serological datapoints reported during a period of acute illness were identified on manual review of the primary care records and excluded from analysis. In the instance of multiple datapoints within this pre-admission period, the latest eligible value was inputted for analysis. The in-house hospital laboratory reference ranges were applied to facilitate data interpretation and differentiate normal from abnormal test results. Patients with elevated baseline inflammatory marker values were assigned to the inflammageing group, whilst the non-inflammageing cohort were identified with baseline inflammatory marker values within normal range.

Established risk stratification techniques including NELA risk of mortality and CFS score were evaluated as the reference standard within our test cohort. The post-operative outcomes captured included duration of total hospital stay, duration of critical care stay. Data were collected on admission mortality and return to theatre; however, these outcomes were not included for analysis due to their low incidence, as discussed in the study limitations.

Access to the relevant data was granted by Liverpool University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and the NELA database. Baseline biomarker data were captured using E-Exchange, a computer system that interfaces patient primary and secondary care clinical records. Acute admission biomarker data was collated using ICE, a computer system facilitating the requesting and reporting of clinical investigations within secondary care; in cases of non-accessible computerised data, the hand-written clinical notes were consulted. Pre-operative risk stratification scores and post-operative outcome data were accessed using the NELA database and consolidated using the clinical notes. The collected data were stored in spreadsheet format using Microsoft Excel 2018 [

11]. Patients were anonymised and assigned a unique study identifier.

Statistical analysis was facilitated by the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Version 26) [

12]. The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to evaluate the distribution of data using a hypothesis of normality, whilst Levene’s test was applied to assess for equality of variance between comparison groups. Parametric statistical analysis utilised t-testing, with mean and standard deviation acting as measures of data spread; non-parametric statistical analysis utilised Mann-Whitney testing, with median and interquartile range acting as measures of data spread. The conventional p-value threshold of 0.05 was applied to determine statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

A total of 196 patients were included for analysis: 57.7% were female and the median age was 74.5 years (interquartile range [IQR] 12). The most prevalent clinical presenting features were abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and constipation; 58.2% of patients presented with two or more of the listed symptoms. The leading diagnostic indications for emergency laparotomy were small bowel obstruction, followed by visceral perforation and complicated hernia. The cohort exhibited a varied past medical, surgical and medication history. Within the study cohort, the median total hospital and critical care stay measured 15 days (IQR 15) and 1 day (IQR 3) respectively. The participant characteristics have been summarised in Table 2.

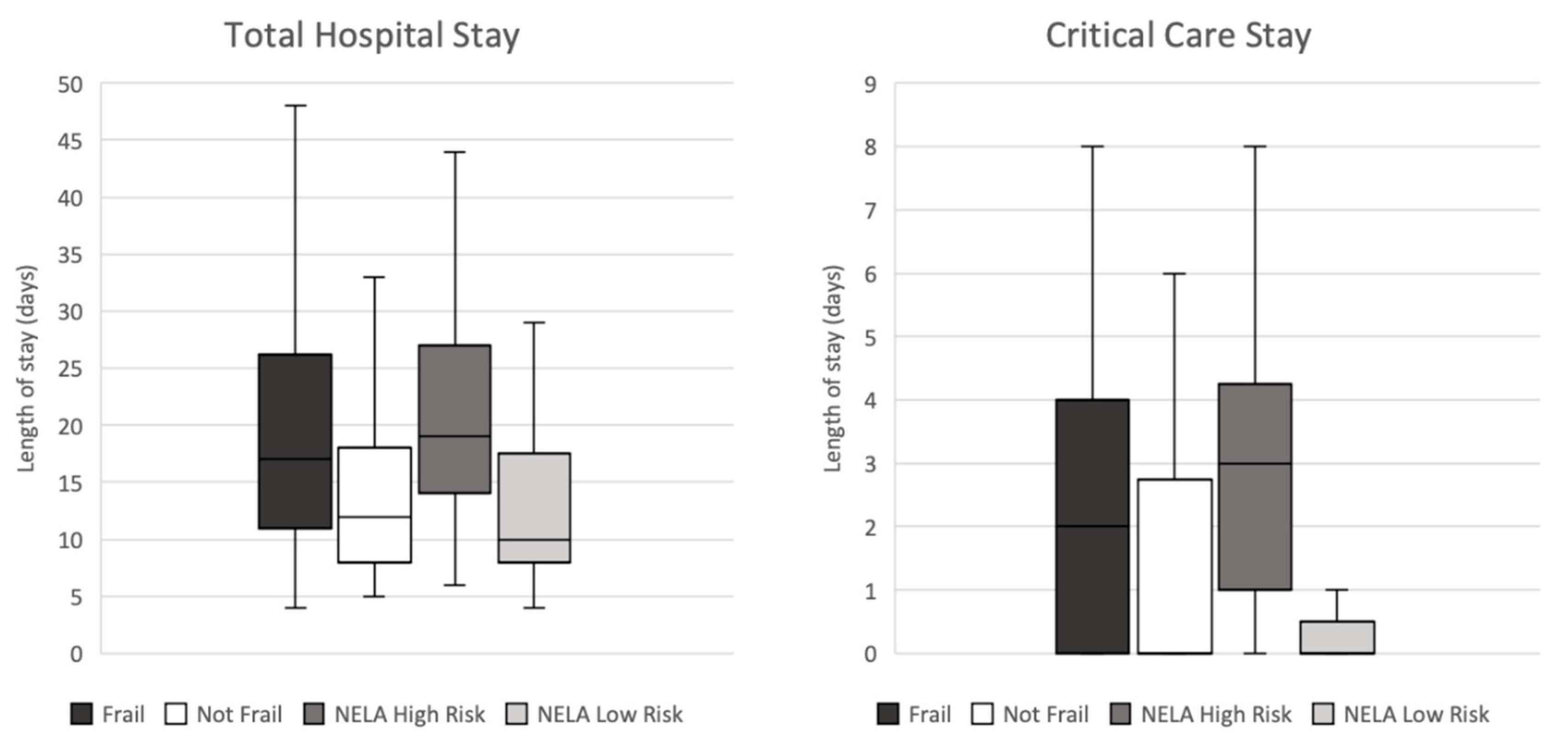

3.2. Clinical frailty scale, NELA risk of mortality & actual mortality

The CFS and NELA risk of mortality were first evaluated to benchmark the current standards of care in the identification and risk stratification of frail patients within our specific test cohort. Frail patients, defined as CFS ≥4, experienced a significantly prolonged stay in critical care (

p=0.003, median 2 days compared to 0 days) and hospital (

p=0.004, median 17 days compared to 12 days) on Mann-Whitney testing. Furthermore, high risk patients, defined as NELA risk of mortality ≥5%, also exhibited a significantly lengthened stay in critical care (

p<0.001, median 3 days compared to 0 days) and hospital (

p<0.001, median 19 days compared to 10 days) on Mann-Whitney testing. The results of these analyses have been visualised in

Figure 2.

The overall admission mortality rate was 0.5% (n = 1) within the study cohort (n = 196). The deceased patient was identified as high risk (NELA risk of morality = 20.3%) prior to undergoing emergency repair of perforation secondary to peptic ulcer disease. In this isolated case, review of the pre-admission serology demonstrated LC 3.2 and no eligible ESR data, meaning they were assigned to the non-inflammageing group in subsequent analyses. The adverse outcome observed in this individual case did not correlate with an elevated LC.

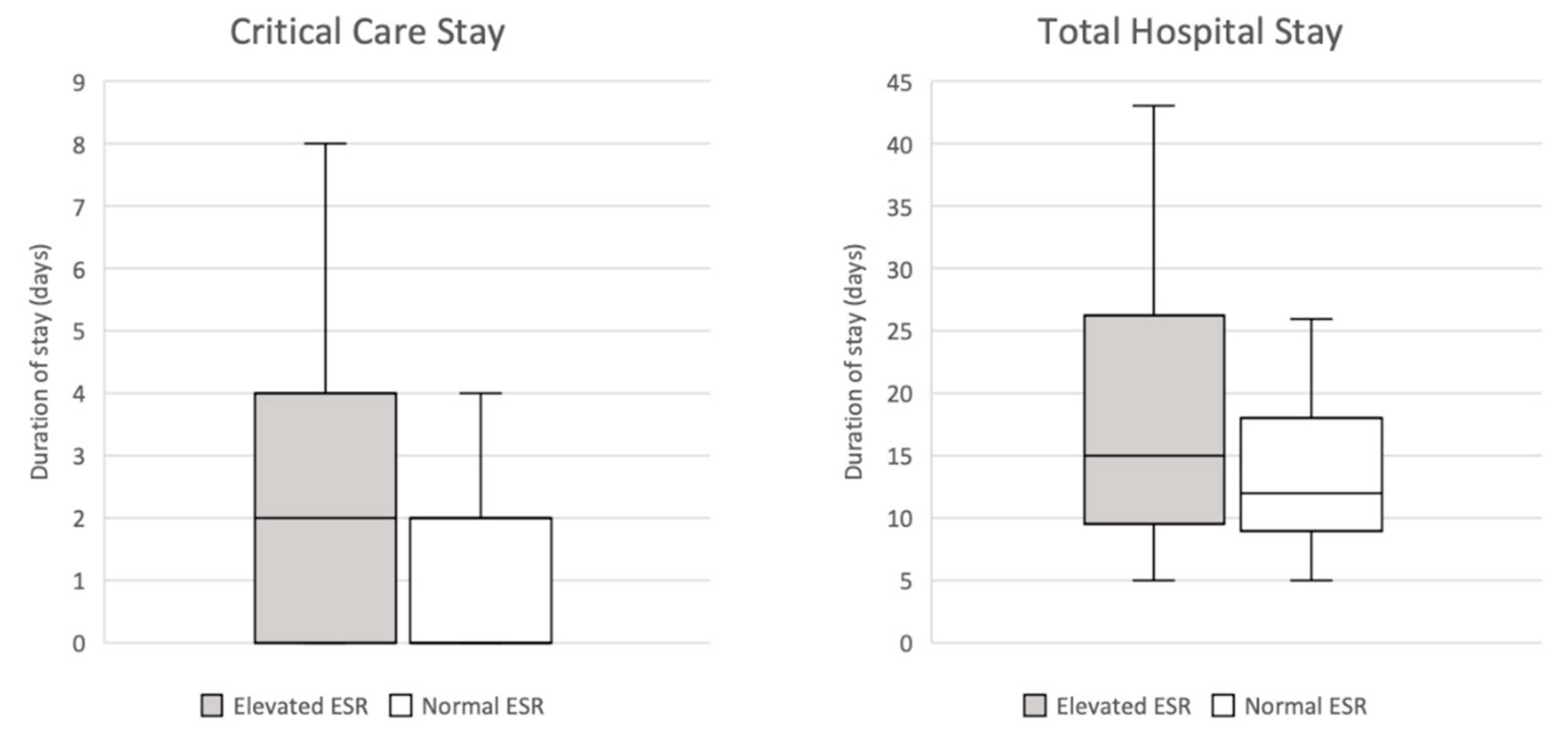

3.3. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

An elevated ESR, defined as ≥16 using the pre-determined reference range, was associated with a significantly prolonged critical care admission on Mann Whitney testing (

p=0.012, median 2 days compared to 0 days). It also demonstrated an observed trend with prolonged total hospital stay, although this analysis did not achieve statistical significance (

p=0.137, median 15 days compared to 12 days). These findings have been illustrated in

Figure 3.

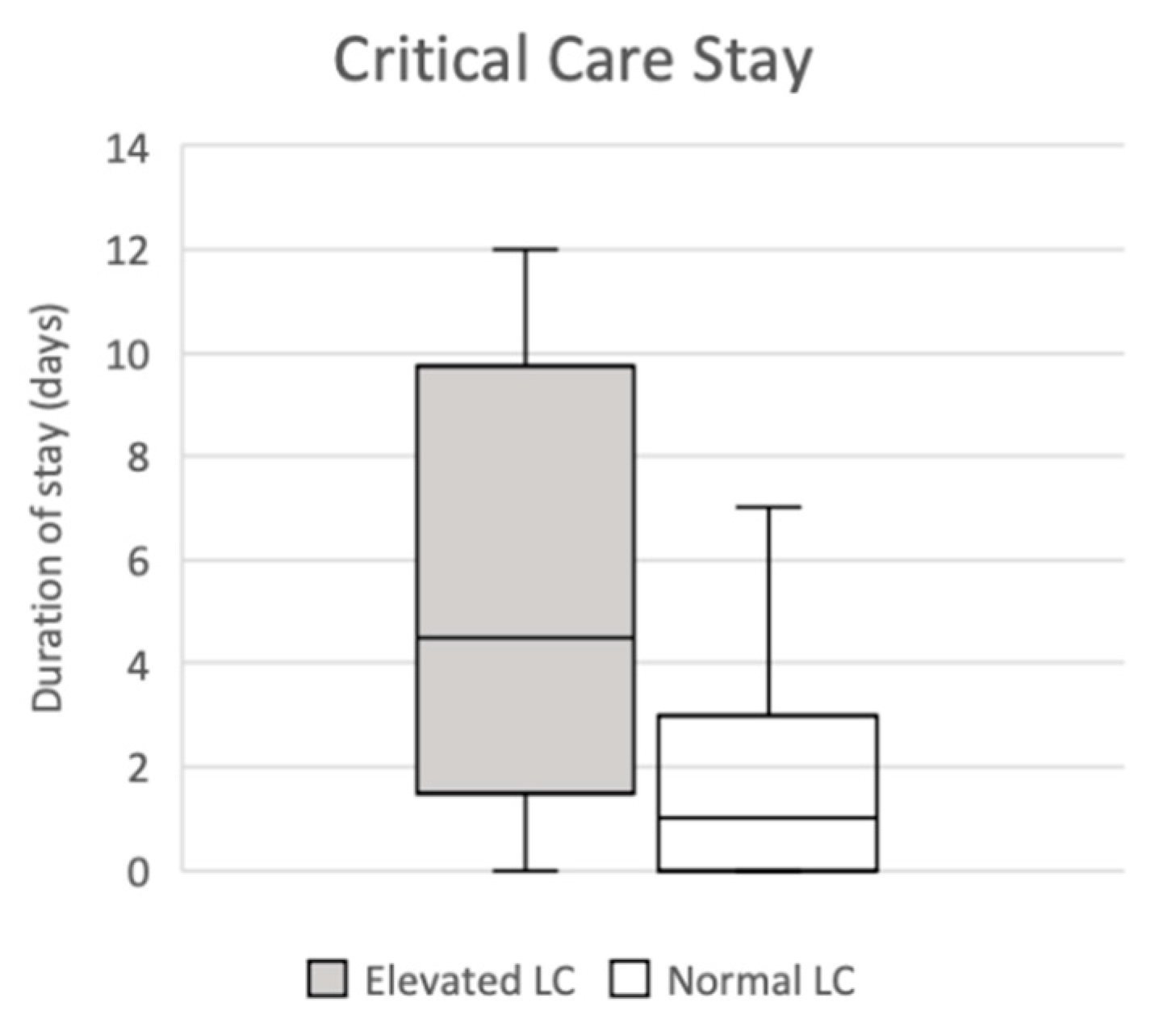

3.4. Lymphocyte count

Mann Whitney testing identified a statistically significant association between an elevated LC, defined as ≥4.1 using the pre-determined reference range, and extended critical care stay (

p=0.035, median 4.5 days compared to 1 day); this has been illustrated in

Figure 4. No correlation of significance was observed on analysis of total hospital stay duration in this group (

p=0.608, median 12.5 days compared to 15 days

).

3.5. C-Reaction protein, total white cell count and neutrophil count

Analysis of the remaining serological parameters including CRP, WCC and NC did not demonstrate any association with length of total hospital and critical care stay of statistical significance. The results of these analyses have been summarised in

Table 5.

4. Discussion

This pragmatic retrospective observational study evaluated pre-admission serological biomarkers of inflammation in the identification and prognostication of frail patients undergoing emergency laparotomy within a five-year time period. The CFS and NELA risk of mortality represented the current standards of care within the United Kingdom in this study; high risk and frail patients, as determined using these techniques, experienced significantly prolonged total hospital and critical care stay. An elevated pre-admission ESR and LC was significantly associated with prolonged critical care admission; these biomarkers may have the potential to support the pre-operative risk stratification of elderly and frail surgical patients in the future.

Emergency laparotomy is a highly invasive surgical technique that requires physiological resilience of the surgical candidate for satisfactory surgical outcome and recovery. The risks associated with emergency laparotomy, such as wound and secondary infections, long-term morbidity and mortality are widely recognised [

13]. The elderly and frail represent a patient cohort with reduced physiological reserve, impairing their ability to tolerate the intense burden of emergency laparotomy; as a result, the likelihood and severity of adverse outcomes is significantly increased [

7].

Effective surgical case selection in this group requires critical evaluation of the potential risks and benefits of surgery and is central to their management. Pre-operative risk stratification currently utilises clinical composite scoring systems such as the NELA risk of morbidity and mortality to support and facilitate this decision-making process. Clinical composite scoring systems can be time consuming, require a comprehensive clinical history and are subjective in nature, bringing their utility in the emergency setting into question. The consideration of identifying patients with inflammageing offers a quantitative approach to the identification of frail patients using readily accessible serological data. Given that inflammageing patients have previously been shown to experience worse outcomes following periods of acute illness, it may be hypothesised they are also at increased risk of adverse outcomes following surgery. The findings reported in the present study are supportive of this notion: an elevated pre-admission ESR and LC identified a group of inflammageing patients that did indeed experience worse outcomes with prolonged critical care admission. With further research and larger prospective studies, inflammageing may demonstrate the potential to assist pre-operative risk stratification of elderly patients

The CRP and ESR are often regarded as the most widely recognised and commonly requested serological inflammatory markers. These two assays are capable of detecting and quantifying active inflammation within the body, in turn supporting clinicians with their clinical decision-making [

14]. Interestingly, the present study reports patients with an elevated ESR were associated with significantly worse post-operative outcomes, whilst those with an elevated CRP were not. One possible explanation for this lies within the physiology underpinning the two assays. CRP synthesis in the liver is stimulated by pro-inflammatory inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6, interleukin-1β and tumour necrosis factor α [

15]. CRP is a dynamic biomarker that is highly sensitive to slight variations in inflammatory states, translating to data values that increase in accordance with increasing severity of inflammation [

16,

17]. The rapid ascent and fall of CRP, in proportionate response to inflammation, make it a popular assay in the diagnosis and surveillance of acute inflammatory disorders [

18]. ESR, as its name suggests, measures the sedimentation rate of erythrocytes within plasma. This process is dictated by the aggregation of red blood cells forming rouleaux, and is mediated by acute phase reactants including fibrinogen [

19]. Fibrinogen is a pro-thrombotic protein synthesised in the liver that, in its capacity as an acute phase reactant, is slow-reacting and insensitive to mildly differing inflammatory states [

20]. It is therefore plausible that, in states of established, chronic inflammation, ESR has the potential to offer a more reliable insight into an individual’s chronic health status, whilst CRP risks labile readings that may over-represent short-term variations. Additional research is recommended to further evaluate the association between ESR and clinical frailty, and its potential clinical utility in surgical risk stratification.

Hasselgager

et al. investigated serological immune parameters such as CRP, interleukin-6, interleukin-10, interferon-γ induced protein 10kDa, tumour necrosis factor α and soluble urokinase plasminogen receptor activator in the prognostication of laparotomy patients [

21]. This pilot study of 100 patients reported a regression model that utilised these biomarkers in combination with patient demographics and clinical composite scoring systems (American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Performance Status) demonstrating improved predictive accuracy for major complications and mortality [

21]. Although these findings evidence the clinical potential of immunological serology in pre-operative risk stratification, they also highlight two persisting challenges: (i) the need for non-routine, selective investigations required for application of the reported model; (ii) the reliance on clinical composite scoring systems as an adjunct to improve predictive performance. Simpson

et a.l evaluated the neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and CRP:albumin ratio (CAR) as predictors of mortality in 136 elderly patients undergoing emergency laparotomy [

22]. An elevated pre-operative NLR was significantly associated with inpatient, 30-day and 90-day mortality in patients with visceral perforation; however, it demonstrated no significance in cases without peritoneal contamination [

22]. No association was observed between CAR and post-operative morbidity and mortality [

22]. Further research, published by Vaughan-Shaw

et al, found NLR to be an independent predictor of mortality at 30-day, 6-month and 12-month time points in patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery [

23]; this study included a wide variety of emergency surgical cases and procedures, reporting laparotomy itself to also be a predictor of adverse outcome [

23].

This study met its pre-determined aim to investigate serum biomarkers of inflammation in the prognostication of elderly patients undergoing emergency laparotomy. Given its single-centre design, the findings reported would benefit from external validation. The outcomes reported in this research included duration of hospital and critical care admission; additional prognostic outcomes of potential interest might include rates of mortality (during admission, 30-day, 3-month, 6-month and 12-month intervals) and post-operative complications. A further consideration is that this study provides only a snapshot insight into the index admission without scope for follow-up. In light of this and the low incidence rate within the included cohort, these parameters were analysed; as a result, duration of hospital and critical care stay acted as a proxy for post-operative outcome. Future research with larger and independent data may address this limitation and build upon the present study. This exploratory study recruited a five-year cohort of real-world patients to evaluate potential prognostic biomarkers in a manner that would represent their future use in clinical practice. As such, patient demographic data including co-morbidities and medication history were collected for descriptive purposes but not adjusted for within the analysis.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated readily available serological markers of inflammation as potential prognostic biomarkers. A raised pre-admission ESR and LC identifies a cohort of elderly patients with inflammageing that experience worse outcomes following emergency laparotomy. Despite this, the molecular identification of biologically frail and prognostication of elderly surgical patients remains a challenge and represents an area of research deserving of future attention; such research may build upon the foundations of this work and explore novel and innovative biochemical and genetic assays.

References

- Xue Q-L. The frailty syndrome: definition and natural history. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2011;27(1):1-15. [CrossRef]

- Parmar KL, Law J, Carter B, Hewitt J, Boyle JM, Casey P, et al. Frailty in Older Patients Undergoing Emergency Laparotomy: Results From the UK Observational Emergency Laparotomy and Frailty (ELF) Study. Annals of Surgery. 2021;273(4). [CrossRef]

- Green G, Shaikh I, Fernandes R, Wegstapel H. Emergency laparotomy in octogenarians: A 5-year study of morbidity and mortality. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5(7):216-21. [CrossRef]

- Church S, Rogers E, Rockwood K, Theou O. A scoping review of the Clinical Frailty Scale. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):393. [CrossRef]

- Thahir A, Pinto-Lopes R, Madenlidou S, Daby L, Halahakoon C. Mortality risk scoring in emergency general surgery: Are we using the best tool? J Perioper Pract. 2021;31(4):153-8. [CrossRef]

- Eugene N, Oliver CM, Bassett MG, Poulton TE, Kuryba A, Johnston C, et al. Development and internal validation of a novel risk adjustment model for adult patients undergoing emergency laparotomy surgery: the National Emergency Laparotomy Audit risk model. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2018;121(4):739-48. [CrossRef]

- Darbyshire AR, Kostakis I, Pucher PH, Prytherch D, Mercer SJ. P-POSSUM and the NELA Score Overpredict Mortality for Laparoscopic Emergency Bowel Surgery: An Analysis of the NELA Database. World J Surg. 2022;46(3):552-60. [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci L, Fabbri E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2018;15(9):505-22. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi C, Campisi J. Chronic Inflammation (Inflammaging) and Its Potential Contribution to Age-Associated Diseases. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 2014;69(Suppl_1):S4-S9. [CrossRef]

- Yende S, Kellum JA, Talisa VB, Peck Palmer OM, Chang C-CH, Filbin MR, et al. Long-term Host Immune Response Trajectories Among Hospitalized Patients With Sepsis. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(8):e198686. [CrossRef]

- Microsoft. Microsoft Excel. Available from: https://office.microsoft.com/excel: Microsoft Corp.; 2018.

- IBM. SPSS Statistics, Version 28. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/uk-en/spss: NY: IBM Corp.; 2021.

- Ahmed A, Azim A. Emergency Laparotomies: Causes, Pathophysiology, and Outcomes. Indian journal of critical care medicine: peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. 2020;24(Suppl 4):S183-s9. [CrossRef]

- Watson J, Round A, Hamilton W. Raised inflammatory markers. BMJ. 2012;344:e454. [CrossRef]

- Salazar J, Martínez MS, Chávez-Castillo M, Núñez V, Añez R, Torres Y, et al. C-Reactive Protein: An In-Depth Look into Structure, Function, and Regulation. Int Sch Res Notices. 2014;2014:653045. [CrossRef]

- Sproston NR, Ashworth JJ. Role of C-Reactive Protein at Sites of Inflammation and Infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:754. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein. Aust Prescr. 2015;38(3):93-4. [CrossRef]

- Bray C, Bell LN, Liang H, Haykal R, Kaiksow F, Mazza JJ, et al. Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate and C-reactive Protein Measurements and Their Relevance in Clinical Medicine. Wmj. 2016;115(6):317-21.

- Tishkowski KG, Vikas. Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate: StatPearls Publishing; 2022 [updated 08/05/2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557485/ (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Lapić I, Padoan A, Bozzato D, Plebani M. Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate and C-Reactive Protein in Acute Inflammation. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153(1):14-29. [CrossRef]

- Petring Hasselager R, Bang Foss N, Andersen O, Cihoric M, Bay-Nielsen M, Nielsen HJ, et al. Mortality and major complications after emergency laparotomy: A pilot study of risk prediction model development by preoperative blood-based immune parameters. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2021;65(2):151-61. [CrossRef]

- Simpson G, Saunders R, Wilson J, Magee C. The role of the neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and the CRP:albumin ratio (CAR) in predicting mortality following emergency laparotomy in the over 80 age group. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;44(6):877-82. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan-Shaw PG, Rees JR, King AT. Neutrophil lymphocyte ratio in outcome prediction after emergency abdominal surgery in the elderly. Int J Surg. 2012;10(3):157-62. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).