Submitted:

31 March 2023

Posted:

04 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Parasites and Experimental Infection

Molecular Phylogenetic and Phylogeographic Analyses

3. Results

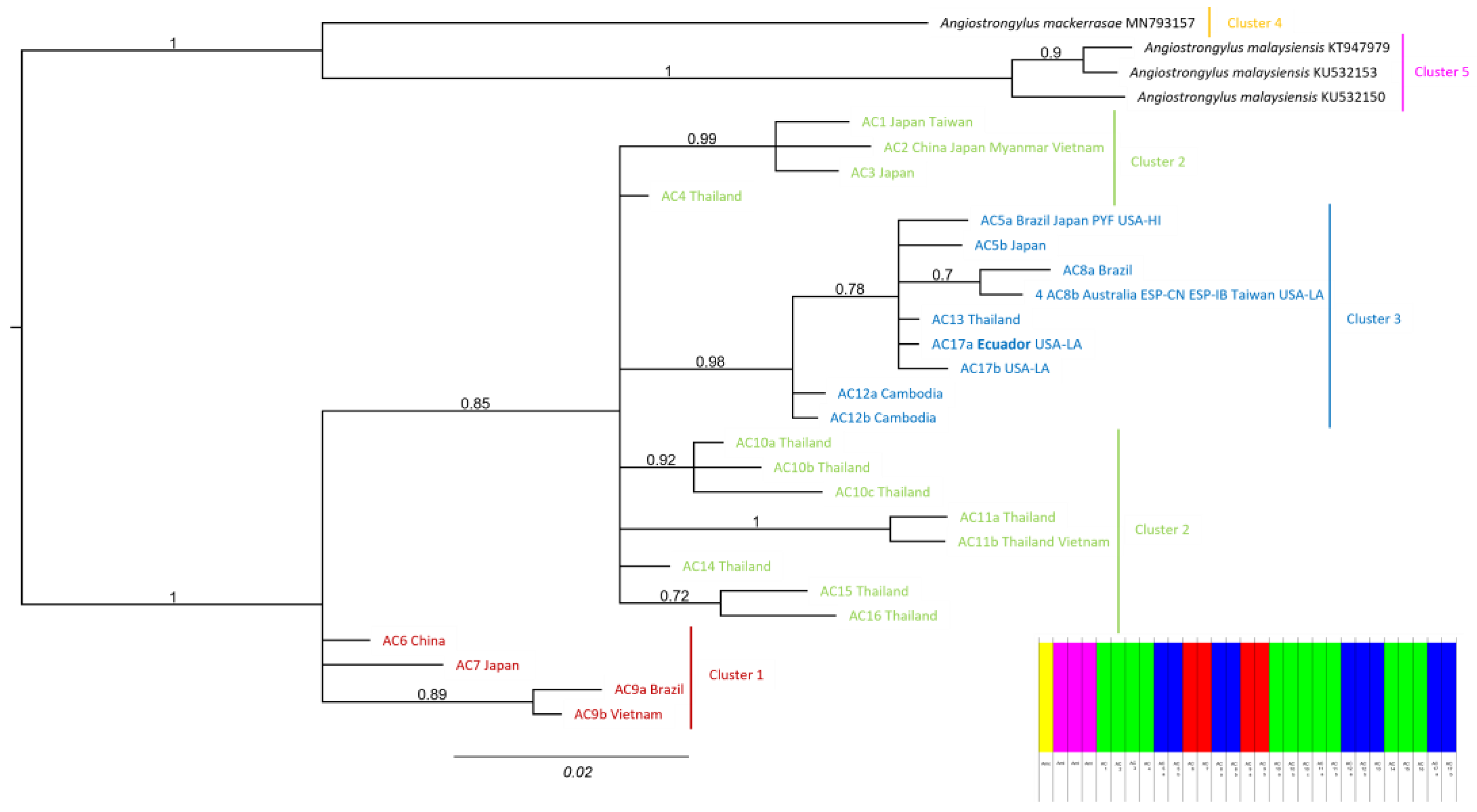

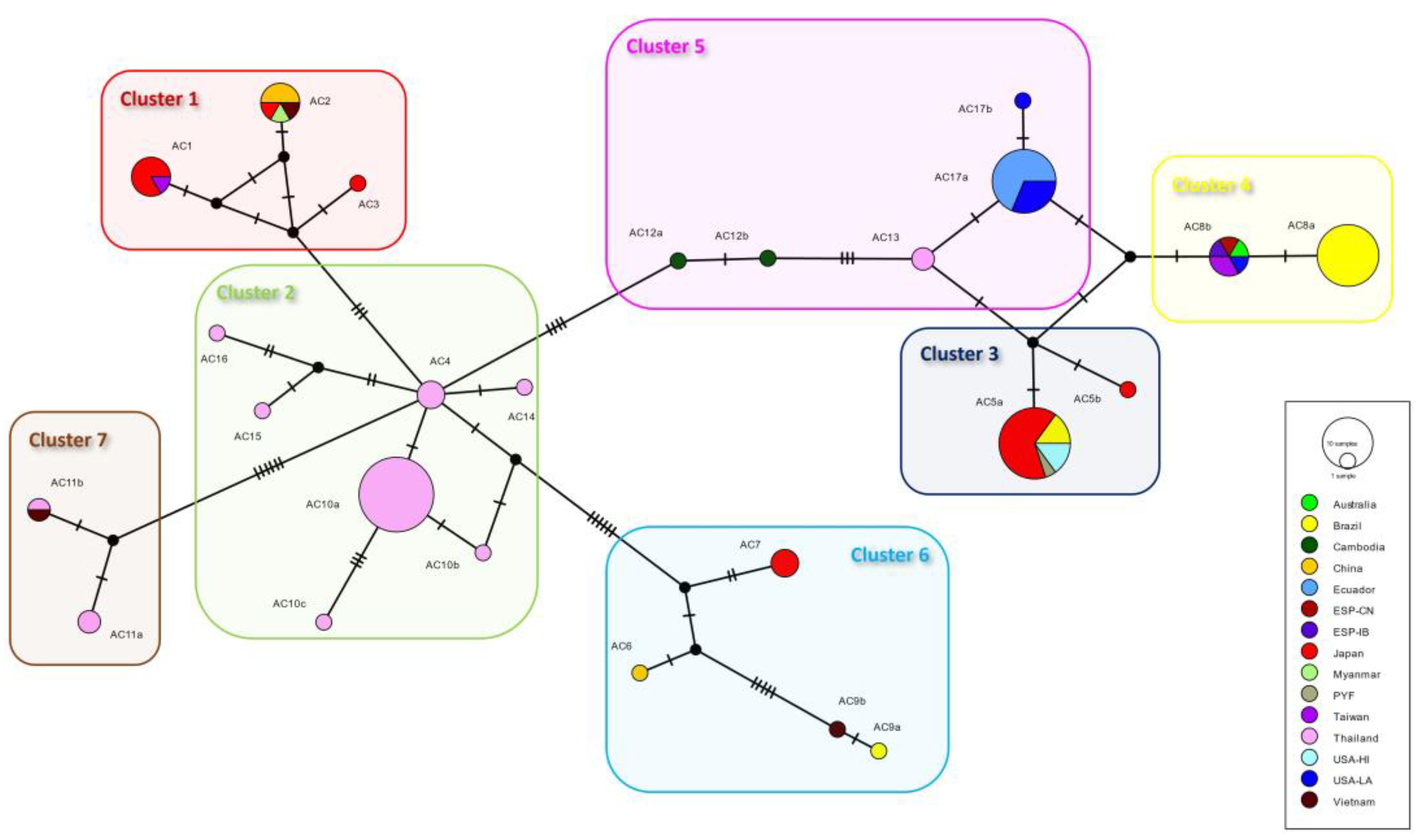

3.1. Molecular Phylogenetic Analyses

3.2. Phylogeographic Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, H.-T. Un Nouveau Nématode Pulmonaire, Pulmonema Cantonensis, n. g., n. Sp. Annales de Parasitologie Humaine et Comparée 1935, 13, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eamsobhana, P. Eosinophilic Meningitis Caused by Angiostrongylus Cantonensis--a Neglected Disease with Escalating Importance. Tropical biomedicine 2014, 31, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martins, Y.C.; Tanowitz, H.B.; Kazacos, K.R. Central Nervous System Manifestations of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis Infection. Acta Tropica 2015, 141, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.P.; Wu, Z.D.; Wei, J.; Owen, R.L.; Lun, Z.R. Human Angiostrongylus Cantonensis: An Update. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 2011 31:4 2012, 31, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicata, J.E. Biology and Distribution of the Rat Lungworm, Angiostrongylus Cantonensis, and Its Relationship to Eosinophilic Meningoencephalitis and Other Neurological Disorders of Man and Animals**Paper Presented at the First International Congress of Parasitology, Rome, Italy. In Advances in Parasitology; Dawes, B., Ed.; Academic Press, 19–26 September 1965; pp. 223–248. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Júnior, A.; Simões, R.O.; Oliveira, A.P.M.; Motta, E.M.; Fernandez, M.A.; Pereira, Z.M.; Monteiro, S.S.; Torres, E.J.L.; Thiengo, S.C. First Report of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae) in Achatina Fulica (Mollusca: Gastropoda) from Southeast and South Brazil. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2010, 105, 938–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, R.H.; Ansdell, V.; Panosian Dunavan, C.; Rollins, R.L. Neuroangiostrongyliasis: Global Spread of an Emerging Tropical Disease. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2022, tpmd220360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.P.; Lai, D.H.; Zhu, X.Q.; Chen, X.G.; Lun, Z.R. Human Angiostrongyliasis. Lancet Infect Dis 2008, 8, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansdell, V.; Wattanagoon, Y. Angiostrongylus Cantonensis in Travelers: Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 2018, 31, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solorzano, L.F.; Martini Robles, L.; Hernandez, H.; Sarracent, J.; Muzzio, J.; Rojas, L. Angiostrongylus cantonensis: un parásito emergente en Ecuador. Revista Cubana Medicina Tropical 2014, 66. [Google Scholar]

- Martini-Robles, L.; Gómez-Landires, E.; Muzzio-Aroca, J.; Solórzano-Álava, L. Descripcion Del Primer Foco de Transmision Natural de Angiostrongylus Cantonensis En Ecuador. In Angiostrongylus cantonensis - Emergencia en América; Martini-Robles, L., Dorta-Contreras, A.J., Eds.; Editorial Academia La Habana: La Habana, 2016; ISBN 978-959-270-368-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pincay, T.; García, L.; Narváez, E.; Decker, O.; Martini, L.; Moreira, J.M. Angiostrongiliasis Por Parastrongylus (Angiostrongylus) Cantonensis En Ecuador. Primer Informe En Sudamérica. Tropical Medical Int Health 2009, 14, S37. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero, M.; Vargas, F.M.; Rosero, A.R.; Nuques, M. de L.; Bolaños, E.S.; Briones, M.T.; Martínez, W.Z.; Gómez, A.O. Meningitis eosinofílica por angiostrongylus cantonensis. Reporte de caso de autopsia. Medicina 2008, 13, 312–318. [Google Scholar]

- Solórzano, L.; Sánchez-Amador, F.; Valverde, T. Angiostrongylus (Parastrongylus) cantonensis en huéspedes intermediarios y definitivos en Ecuador, 2014-2017. Biomédica 2019, 39, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzzio, J. Hospederos intermediarios de Angiostrongylus cantonensis en Ecuador; Editorial Academica Española: Saarbrücken, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thiengo, S.C.; Faraco, F.A.; Salgado, N.C.; Cowie, R.H.; Fernandez, M.A. Rapid Spread of an Invasive Snail in South America: The Giant African Snail, Achatina Fulica, in Brasil. Biological Invasions 2007, 9, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, V.L.C.; Giese, E.G.; Melo, F.T.V.; Simões, R. de O.; Thiengo, S.C.; Maldonado-Júnior, A.; Santos, J.N. Endemic Angiostrongyliasis in the Brazilian Amazon: Natural Parasitism of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis in Rattus Rattus and R. Norvegicus, and Sympatric Giant African Land Snails, Achatina Fulica. Acta tropica 2013, 125, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qvarnstrom, Y.; Sullivan, J.J.; Bishop, H.S.; Hollingsworth, R.; da Silva, A.J. PCR-Based Detection of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis in Tissue and Mucus Secretions from Molluscan Hosts. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2007, 73, 1415–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qvarnstrom, Y.; da Silva, A.J.C.A.; Teem, J.L.; Hollingsworth, R.; Bishop, H.S.; Graeff-Teixeira, C.; Aramburu Da Silva, A.C. Improved Molecular Detection of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis in Mollusks and Other Environmental Samples with a Species-Specific Internal Transcribed Spacer Based TaqMan Assay. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2010, 76, 5287–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qvarnstrom, Y.; Xayavong, M.; da Silva, A.C.A.; Park, S.Y.; Whelen, A.C.; Calimlim, P.S.; Sciulli, R.H.; Honda, S.A.A.; Higa, K.; Kitsutani, P.; et al. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Detection of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis DNA in Cerebrospinal Fluid from Patients with Eosinophilic Meningitis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2016, 94, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qvarnstrom, Y.; Bishop, H.S.; da Silva, A.J. Detection of Rat Lungworm in Intermediate, Definitive, and Paratenic Hosts Obtained from Environmental Sources. Hawai’i Journal of Medicine & Public Health: A Journal of Asia Pacific Medicine & Public Health 2013, 72, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sears, W.J.; Qvarnstrom, Y.; Nutman, T.B. RPAcan3990: An Ultrasensitive Recombinase Polymerase Assay To Detect Angiostrongylus Cantonensis DNA. J Clin Microbiol 2021, 59, e0118521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-Y.; Song, H.-Q.; Zhang, R.-L.; Chen, M.-X.; Xu, M.-J.; Ai, L.; Chen, X.-G.; Zhan, X.-M.; Liang, S.-H.; Yuan, Z.-G.; et al. Specific Detection of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis in the Snail Achatina Fulica Using a Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Assay. Molecular and Cellular Probes 2011, 25, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Zhang, Y.; Steinmann, P.; Utzinger, J.; Zhou, X.-N. The Genetic Variation of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis in the People’s Republic of China. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.Y.; Zhang, R.L.; Chen, M.X.; li, J.; Ai, L.; Wu, C.Y.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Lin, Q. Characterisation of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis Isolates from China by Sequences of Internal Transcribed Spacers of Nuclear Ribosomal DNA. Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances 2011, 10, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; He, Z.; Zhang, S.; Lun, Z.; Wu, Z.; Fan, C.-K.; Brown, C.L.; Cheng, P.; Peng, S.; Yang, T. Phylogeography of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) in Southern China and Some Surrounding Areas. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2017, 11, e0005776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontanilla, I.K.C.; Wade, C.M. The Small Subunit (SSU) Ribosomal (r) RNA Gene as a Genetic Marker for Identifying Infective 3rd Juvenile Stage Angiostrongylus Cantonensis. Acta Tropica 2008, 105, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eamsobhana, P.; Lim, P.E.; Yong, H.S. Phylogenetics and Systematics of Angiostrongylus Lungworms and Related Taxa (Nematoda: Metastrongyloidea) Inferred from the Nuclear Small Subunit (SSU) Ribosomal DNA Sequences. Journal of Helminthology 2015, 89, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galtier, N.; Nabholz, B.; Glémin, S.; Hurst, G.D.D. Mitochondrial DNA as a Marker of Molecular Diversity: A Reappraisal. Molecular Ecology 2009, 18, 4541–4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blouin, M.S. Molecular Prospecting for Cryptic Species of Nematodes: Mitochondrial DNA versus Internal Transcribed Spacer. International Journal for Parasitology 2002, 32, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, H.S.; Eamsobhana, P.; Song, S.-L.; Prasartvit, A. Molecular Phylogeography of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) and Genetic Relationships with Congeners Using Cytochrome b Gene Marker. Acta Tropica 2015, 148, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.R. de; Souza, J.G.R. de; Santos, H.A.; Torres, E.J.L.; Vilela, R. do V.; Cruz, O.M.S.; Rodrigues, L.; Pereira, C.A. de J.; Maldonado-Júnior, A.; Lima, W. dos S. Angiostrongylus Minasensis n. Sp.: New Species Found Parasitizing Coatis (Nasua Nasua) in an Urban Protected Area in Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Parasitologia Veterinária 2020, 29, e018119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eamsobhana, P.; Lim, P.-E.; Solano, G.; Zhang, H.; Gan, X.; Yong, H.S. Molecular Differentiation of Angiostrongylus Taxa (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) by Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I (COI) Gene Sequences. Acta tropica 2010, 116, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, R.L.; Carvalho, O. dos S.; Mendonça, C.L.G.F.; Graeff-Teixeira, C.; Silva, M.C.; Ben, R.; Maurer, R.; Lima, W. dos S.; Lenzi, H.L. Molecular Differentiation of Angiostrongylus Costaricensis, A. Cantonensis, and A. Vasorum by Polymerase Chain Reaction-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2003, 98, 1039–1043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valentyne, H.; Spratt, D.M.; Aghazadeh, M.; Jones, M.K.; Šlapeta, J. The Mitochondrial Genome of Angiostrongylus Mackerrasae Is Distinct from A. Cantonensis and A. Malaysiensis. Parasitology 2020, 147, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monte, T.C.C.; Simões, R. de O.; Oliveira, A.P.M.; Novaes, C.F.; Thiengo, S.C.; Silva, A.J.; Cordeiro-Estrela, P.; Maldonado-Júnior, A. Phylogenetic Relationship of the Brazilian Isolates of the Rat Lungworm Angiostrongylus Cantonensis (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae) Employing Mitochondrial COI Gene Sequence Data. Parasites & vectors 2012, 5, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitta, A.; Srisongcram, N.; Thiproaj, J.; Wongma, A.; Polsut, W.; Fukruksa, C.; Yimthin, T.; Mangkit, B.; Thanwisai, A.; Dekumyoy, P. Phylogeny of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis in Thailand Based on Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I Gene Sequence. The Southeast Asian journal of tropical medicine and public health 2016, 47, 377–386. [Google Scholar]

- Eamsobhana, P.; Song, S.L.; Yong, H.S.; Prasartvit, A.; Boonyong, S.; Tungtrongchitr, A. Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit I Haplotype Diversity of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae). Acta Tropica 2017, 171, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokiwa, T.; Harunari, T.; Tanikawa, T.; Komatsu, N.; Koizumi, N.; Tung, K.-C.; Suzuki, J.; Kadosaka, T.; Takada, N.; Kumagai, T.; et al. Phylogenetic Relationships of Rat Lungworm, Angiostrongylus Cantonensis, Isolated from Different Geographical Regions Revealed Widespread Multiple Lineages. Parasitology International 2012, 61, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legislation for the Protection of Animals Used for Scientific Purposes - Environment - European Commission Available online:. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/chemicals/lab_animals/legislation_en.htm (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Aguiar, P.H.; Morera, P.; Pascual, J. First Record of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis in Cuba. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 1981, 30, 963–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubelaker, J.E. Systematics of Species Referred to the Genus Angiostrongylus. The Journal of Parasitology 1986, 72, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.H.E.; Chaisiri, K.; Dusitsittipon, S.; Jakkul, W.; Charoennitiwat, V.; Komalamisra, C.; Thaenkham, U. Mitochondrial Ribosomal Genes as Novel Genetic Markers for Discrimination of Closely Related Species in the Angiostrongylus Cantonensis Lineage. Acta Tropica 2020, 211, 105645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eamsobhana, P.; Yong, H.-S.; Song, S.-L.; Gan, X.-X.; Prasartvit, A.; Tungtrongchitr, A. Molecular Phylogeography and Genetic Diversity of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis and A. Malaysiensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) Based on 66-KDa Protein Gene. Parasitology International 2019, 68, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C.; et al. Geneious Basic: An Integrated and Extendable Desktop Software Platform for the Organization and Analysis of Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple Sequence Alignment with High Accuracy and High Throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddison, W.P.; Maddison, D.R. Mesquite: A Modular System for Evolutionary Analysis 2021.

- Corander, J.; Marttinen, P.; Sirén, J.; Tang, J. Enhanced Bayesian Modelling in BAPS Software for Learning Genetic Structures of Populations. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corander, J.; Sirén, J.; Arjas, E. Bayesian Spatial Modeling of Genetic Population Structure. Computational Statistics 2008, 23, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Hohna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference and Model Choice Across a Large Model Space. Systematic Biology 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Pfeiffer, W.; Schwartz, T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for Inference of Large Phylogenetic Trees. In Proceedings of the 2010 Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE); IEEE, November 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior Summarization in Bayesian Phylogenetics Using Tracer 1.7. Systematic Biology 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. POPART: Full-Feature Software for Haplotype Network Construction. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelt, H.-J.; Forster, P.; Röhl, A. Median-Joining Networks for Inferring Intraspecific Phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 1999, 16, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, J.; Ferrer-Mata, A.; Sánchez-DelBarrio, J.C.; Guirao-Rico, S.; Librado, P.; Ramos-Onsins, S.E.; Sánchez-Gracia, A. DnaSP 6: DNA Sequence Polymorphism Analysis of Large Data Sets. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2017, 34, 3299–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, F. Statistical Method for Testing the Neutral Mutation Hypothesis by DNA Polymorphism. Genetics 1989, 123, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.-X. Statistical Tests of Neutrality of Mutations Against Population Growth, Hitchhiking and Background Selection. Genetics 1997, 147, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodpai, R.; Intapan, P.M.; Thanchomnang, T.; Sanpool, O.; Sadaow, L.; Laymanivong, S.; Aung, W.P.; Phosuk, I.; Laummaunwai, P.; Maleewong, W. Angiostrongylus Cantonensis and A. Malaysiensis Broadly Overlap in Thailand, Lao PDR, Cambodia and Myanmar: A Molecular Survey of Larvae in Land Snails. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0161128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wit, L.A.; Ricketts, T.H. Trade and Deforestation Predict Rat Lungworm Disease, an Invasive-Driven Zoonosis, at Global and Regional Scales. Frontiers in Public Health 2021, 9, 680986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanol, J.; Fernandez, M.A.; de Oliveira, A.P.M.; Russo, C.A. de M.; Thiengo, S.C. O Caramujo Exótico Invasor Achatina Fulica (Stylommatophora, Mollusca) No Estado Do Rio de Janeiro (Brasil): Situação Atual. Biota Neotropica 2010, 10, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barçante, J.M. de P.; Barçante, T.A.; Dias, S.R.C.; Lima, W. dos S. Ocorrência de Achatina Fulica Bowdich, 1822 (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Achatinoidea) No Estado de Minas Gerais, Brasil. Boletim do Museu de Biologia Mello Leitão 2005, 18, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Teles, H.M.S.; Fontes, L.R. Implicações Da Introdução e Dispersão de Achatina Fulica Bowdich, 1822 No Brasil. Boletim do Instituto Adolfo Lutz 2002, 12, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Thiengo, S.C.; Simões, R. de O.; Fernandez, M.A.; Maldonado-Júnior, A. Angiostrongylus Cantonensis and Rat Lungworm Disease in Brazil. Hawai’i journal of medicine & public health : a journal of Asia Pacific Medicine & Public Health 2013, 72, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Arruda, J.O.; Santos, L. First Record of Achatina Fulica Bowdich, 1822 (Mollusca, Achatinidae), for the State of Rio Grande Do Sul, Brazil. Biotemas 2022, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrero, F.J.; Breure, A.S.H.; Christensen, C.C.; Correoso, M.; Avila, V.M. Into the Andes: Three New Introductions of Lissachatina Fulica (Gastropoda, Achatinidae) and Its Potential Distribution in South America. Tentacle 2009, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, R.L.; Mendonça, C.L.G.F.; Goveia, C.O.; Lenzi, H.L.; Graeff-Teixeira, C.; Lima, W.S.; Mota, E.M.; Pecora, I.L.; De Medeiros, A.M.Z.; Carvalho, O.D.S. First Record of Molluscs Naturally Infected with Angiostrongylus Cantonensis (Chen, 1935) (Nematoda: Metastrongylidae) in Brazil. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2007, 102, 887–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.-X.; Hu, L.; Yang, K.; Steinmann, P.; Chen, Z.; Wang, L.-Y.; Utzinger, J.; Zhou, X.-N. Invasive Snails and an Emerging Infectious Disease: Results from the First National Survey on Angiostrongylus Cantonensis in China. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2009, 3, e368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirira S., D. Guía de Campo de Los Mamíferos Del Ecuador; Murciélago Blanco: Quito, 2007; ISBN 9978-44-651-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kosoy, M.; Khlyap, L.; Cosson, J.-F.; Morand, S. Aboriginal and Invasive Rats of Genus Rattus as Hosts of Infectious Agents. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 2015, 15, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini L Muzzio J, Solorzano L., G.E. Descripcion Del Primer Foco de Transmision Natural de Angiostrongylus Cantonensis En Ecuador. In Angiostrongylus cantonensis; Emergencia en América, 2016; pp. 209–220. ISBN 978-959-270-368-1.

- Lowe, S.; Browne, M.; Boudjelas, S.; De Poorter, M. 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species: A Selection From The Global Invasive Species Database. Aliens 2000, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowl, T.A.; Crist, T.O.; Parmenter, R.R.; Belovsky, G.; Lugo, A.E. The Spread of Invasive Species and Infectious Disease as Drivers of Ecosystem Change. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2008, 6, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchio, E.; Crotta, M.; Romeo, C.; Drewe, J.A.; Guitian, J.; Ferrari, N. Invasive Alien Species and Disease Risk: An Open Challenge in Public and Animal Health. PLOS Pathogens 2020, 16, e1008922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Červená, B.; Modrý, D.; Fecková, B.; Hrazdilová, K.; Foronda, P.; Alonso, A.M.; Lee, R.; Walker, J.; Niebuhr, C.N.; Malik, R.; et al. Low Diversity of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis Complete Mitochondrial DNA Sequences from Australia, Hawaii, French Polynesia and the Canary Islands Revealed Using Whole Genome next-Generation Sequencing. Parasites & Vectors 2019, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, T.C.C.; Gentile, R.; Garcia, J.S.; Mota, E.; dos Santos, J.N.; Maldonado-Júnior, A. Brazilian Angiostrongylus Cantonensis Haplotypes, Ac8 and Ac9, Have Two Different Biological and Morphological Profiles. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2014, 109, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokiwa, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Yabe, T.; Komatsu, N.; Akao, N.; Ohta, N. First Report of Angiostrongylus Cantonensis (Nematoda: Angiostrongylidae) Infections in Invasive Rodents from Five Islands of the Ogasawara Archipelago, Japan. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rael, R.C.; Peterson, A.C.; Ghersi-Chavez, B.; Riegel, C.; Lesen, A.E.; Blum, M.J. Rat Lungworm Infection in Rodents across Post-Katrina New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2018, 24, 2176–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Identification | GenBank accession number | Province |

| LSA-01 | MW391020 | Esmeraldas |

| LSA-02 | MW390970 | Santa Elena |

| LSA-03 | MW390971 | El Oro_ |

| LSA-04 | MW390972 | Guayas |

| LSA-05 | MW390967 | Zamora |

| LSA-06 | MW390974 | Pastaza_ |

| LSA-07 | MW390969 | Orellana |

| LSA-08 | MW390973 | Manabi |

| LSA-09 | MW390968 | Napo |

| LSA-10 | MW390966 | Los Rios |

| LSA-11 | MW390965 | Sucumbios |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).