Submitted:

04 April 2023

Posted:

05 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

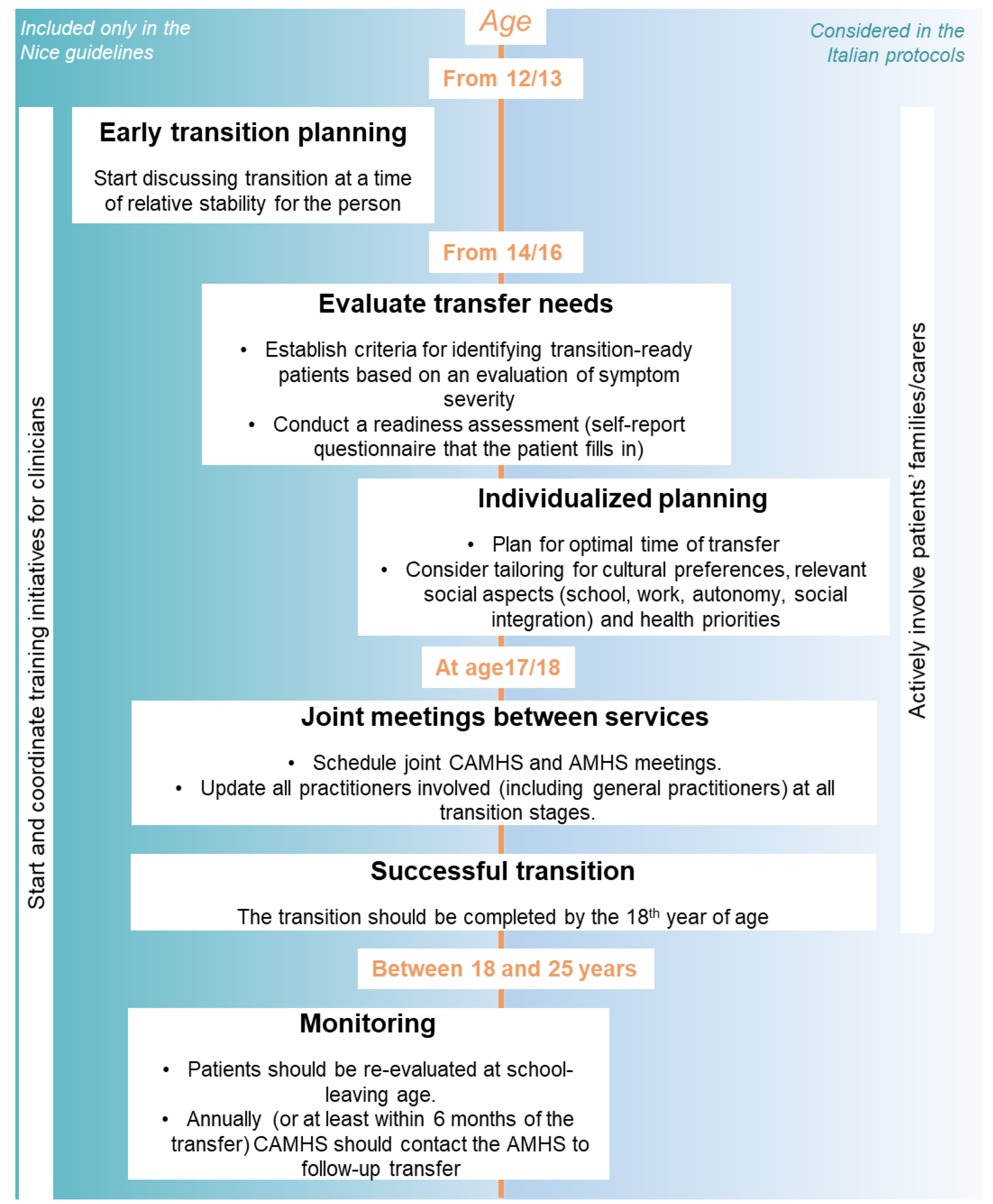

- Young people with ADHD should be transferred to adult mental health services (AMHS) if they continue to have significant ADHD symptoms or other coexisting conditions that require treatment (Evaluation of transfer need);

- The transition should be planned in advance by both the referring and the receiving service (Early transition planning);

- The transfer should be completed by the time the patient is 18 years of age (although precise timing may vary locally) (Transition completed by 18 years);

- A re-assessment of patients’ needs should be done at school-leaving age (Re-evaluation at school-leaving age);

- During the transition to adult services, a formal meeting involving both CAMHS and AMHS should be considered, and complete information about the adult service should be provided to the patient (Joint CAMHS-AMHS meeting);

- The young person and, when appropriate, the parent/carer, should be involved in the transition planning (Family involvement);

- After the transition, a comprehensive patient assessment of personal, educational, occupational, and social functioning (keeping in consideration coexisting conditions) should be carried out at the adult service (Patient assessment after transition/monitoring);

- Specialist ADHD teams for children, young people, and adults should jointly develop age-appropriate training programs for diagnosing and managing ADHD (Training programs).

Materials and Methods:

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [CrossRef]

- Seixas M, Weiss M, Müller U. Systematic review of national and international guidelines on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Psychopharmacol 2012;26:753–65. [CrossRef]

- Roughan LA, Stafford J. Demand and capacity in an ADHD team: reducing the wait times for an ADHD assessment to 12 weeks. BMJ Open Qual 2019;8:e000653. [CrossRef]

- Reale L, Bonati M. ADHD prevalence estimates in Italian children and adolescents: a methodological issue. Ital J Pediatr 2018;44:108. [CrossRef]

- Rocco I, Corso B, Bonati M, Minicuci N. Time of onset and/or diagnosis of ADHD in European children: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21:575. [CrossRef]

- Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, Zhang Y, Li X, Rudan I. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 2021;11:04009. [CrossRef]

- Larsen B, Luna B. Adolescence as a neurobiological critical period for the development of higher-order cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2018;94:179–95. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero N, Yu X, Raphael J, O’Connor T. Impacts of Racial Discrimination in Late Adolescence on Psychological Distress and Wellbeing Outcomes in the Transition to Adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health 2023;72:S2. [CrossRef]

- Young S, Murphy CM, Coghill D. Avoiding the “twilight zone”: recommendations for the transition of services from adolescence to adulthood for young people with ADHD. BMC Psychiatry 2011;11:174. [CrossRef]

- Hansen AS, Telléus GK, Mohr-Jensen C, Lauritsen MB. Parent-perceived barriers to accessing services for their child’s mental health problems. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2021;15:4. [CrossRef]

- Driver D, Berlacher M, Harder S, Oakman N, Warsi M, Chu ES. The Inpatient Experience of Emerging Adults: Transitioning From Pediatric to Adult Care. Journal of Patient Experience 2022;9:237437352211336. [CrossRef]

- Young S, Adamou M, Asherson P, Coghill D, Colley B, Gudjonsson G, et al. Recommendations for the transition of patients with ADHD from child to adult healthcare services: a consensus statement from the UK adult ADHD network. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:301. [CrossRef]

- Swift KD, Hall CL, Marimuttu V, Redstone L, Sayal K, Hollis C. Transition to adult mental health services for young people with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): a qualitative analysis of their experiences. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:74. [CrossRef]

- Eke H, Janssens A, Ford T. Review: Transition from children’s to adult services: a review of guidelines and protocols for young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in England. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2019;24:123–32. [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. NICE Clinical Guideline [CG177] Osteoarthritis: Care and Management in Adults National Institute for Health & Care Excellence, London 2019.

- Eke H, Ford T, Newlove-Delgado T, Price A, Young S, Ani C, et al. Transition between child and adult services for young people with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): findings from a British national surveillance study. Br J Psychiatry 2020;217:616–22. [CrossRef]

- Signorini G, Singh SP, Boricevic-Marsanic V, Dieleman G, Dodig-Ćurković K, Franic T, et al. Architecture and functioning of child and adolescent mental health services: a 28-country survey in Europe. The Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4:715–24. [CrossRef]

- Price A, Mitchell S, Janssens A, Eke H, Ford T, Newlove-Delgado T. In transition with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): children’s services clinicians’ perspectives on the role of information in healthcare transitions for young people with ADHD. BMC Psychiatry 2022;22:251. [CrossRef]

- Singh SP, Tuomainen H, Girolamo G de, Maras A, Santosh P, McNicholas F, et al. Protocol for a cohort study of adolescent mental health service users with a nested cluster randomised controlled trial to assess the clinical and cost-effectiveness of managed transition in improving transitions from child to adult mental health services (the MILESTONE study). BMJ Open 2017;7:e016055. [CrossRef]

- White P, Schmidt A, Shorr J, Ilango S, Beck D, McManus M. Six core elements of health care transitionTM 3.0. 2020.

- Zadra E, Giupponi G, Migliarese G, Oliva F, Rossi PD, Francesco Gardellin, et al. Survey on centres and procedures for the diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD in public services in Italy. Rivista Di Psichiatria 2020. [CrossRef]

- Roberti E, Scarpellini F, Campi R, Giardino M, Clavenna A, Bonati M. Transitioning to Adult Mental Health Services for young people with ADHD: an Italian-based Survey on practices for Pediatric and Adult Services. In Review; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006;3:77–101. [CrossRef]

- Suris J-C, Akre C. Key Elements for, and Indicators of, a Successful Transition: An International Delphi Study. Journal of Adolescent Health 2015;56:612–8. [CrossRef]

- Dunn V. Young people, mental health practitioners and researchers co-produce a Transition Preparation Programme to improve outcomes and experience for young people leaving Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:293. [CrossRef]

- Scarpellini F, Bonati M. Transition care for adolescents and young adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A descriptive summary of qualitative evidence. Child 2022:cch.13070. [CrossRef]

- Reale L, Costantino MA, Sequi M, Bonati M. Transition to Adult Mental Health Services for Young People With ADHD. J Atten Disord 2018;22:601–8. [CrossRef]

- Mulkey M, Baggett AB, Tumin D. Readiness for transition to adult health care among US adolescents, 2016–2020. Child 2023;49:321–31. [CrossRef]

- Bray EA, Everett B, George A, Salamonson Y, Ramjan LM. Co-designed healthcare transition interventions for adolescents and young adults with chronic conditions: a scoping review. Disability and Rehabilitation 2022;44:7610–31. [CrossRef]

- Magon RK, Latheesh B, Müller U. Specialist adult ADHD clinics in East Anglia: service evaluation and audit of NICE guideline compliance. BJPsych Bull 2015;39:136–40. [CrossRef]

- Coghill D. Services for adults with ADHD: work in progress: Commentary on … Specialist adult ADHD clinics in East Anglia. BJPsych Bull 2015;39:140–3. [CrossRef]

- Kok-Pigge AC, Greving JP, de Groot JF, Oerbekke M, Kuijpers T, Burgers JS. A Delphi consensus checklist helped assess the need to develop rapid guideline recommendations. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2023;156:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Farrell ML. Transitioning adolescent mental health care services: The steps to care model. Child Adoles Psych Nursing 2022;35:301–6. [CrossRef]

- Girela-Serrano B, Miguélez C, Porras-Segovia AA, Díaz C, Moreno M, Peñuelas-Calvo I, et al. Predictors of mental health service utilization as adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder transition into adulthood. Early Intervention Psych 2023;17:252–62. [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | Protocol 1 AMHS (40 patients, 15 transitioning) |

Protocol 2 AMHS (3 patients, 2 transitioning) |

Protocol 3 CAMHS (113 patients, 4 transitioning) |

Protocol 4 CAMHS (100 patients, 11 transitioning) |

Protocol 5 CAMHS (300 patients, 2 transitioning) |

Protocol 6 CAMHS (210 patients, 8 transitioning) |

|

| 1 | Evaluation of transfer need | Evaluation of requirements for the specific patient (where a long care pathway is not foreseen, the patient can stay in CAMHS until needed) | Particular attention to severe disorders that require intensive treatment and/or supportive interventions | Evaluate the complexity of each case. If needed, for continuity of care patients can stay in CAMHS after turning 18 | X | only briefly mentioning severity of symptoms | Decided with the family based on the final clinical report |

| 2 | Early transition planning | At least 6 months before turning 18, as early as possible after turning 17 | Starting at age 14; at least 6 months before turning 18 | From 16, usually 6/12 months before turning 18 depending on complexity of the case | ✓ (therapeutic project sent to adult services 6 months before patients turn 18) | Report sheet sent 3 months before patient turns 18 | Between 17 and 18 years. First meeting “months before” turning 18 |

| 3 | Individualized planning | personal, diagnostic and anamnestic data; reason for referral and intervention objective; functioning in different areas of life (social functioning, work, autonomy); care needs and social context; possible substance use or other addictive behavior | Individual plan after evaluation of diagnostic picture | specific pathway for social integration (school, employment, work, etc.) involving the community social services network, schools, employment services, etc. | X (“development of an individualized therapeutic plan, complex and integrated”, but how not explained) | X (“development of a subsequent individualized therapeutic-rehabilitation project”, but how not explained) | history and clinical course, personal and family history, and the most relevant social aspects |

| 4 | Transition completed by 18 years | Yes | X (Between 14 and 25, not specified) | Yes | 1 month after turning 18 maximum | X | X (not mentioned) |

| 5 | Re-evaluation at school-leaving age | X | X (only briefly mentioned, but for transfer and not for re-evaluation) | X | X | X | X |

| 6 | Joint CAMHS-AMHS meeting and information sharing | Functionally integrate all services involved (how not specified) | First contact via email (specifying urgency of transfer); advised to follow up with a phone call. Case discussed within 15 days | Presentation of the case (can be done online), followed by 2 or 3 joint meetings | AMHS receives a therapeutic-rehabilitation project by CAMHS in the year before the patient turns 18; technical meeting with all involved services (at least 3 months before turning 18) | Periodic meetings to monitor the process | 1 technical meeting CAMHS + AMHS, followed by 1 meeting with AMHS, the patient, and the caregivers (the CAMHS can also be present, but only if necessary) |

| 7 | Family involvement | Include and involve families together with the patients (support with social services if necessary) | active participation of family members in the transition and construction of a new care and assistance program | Families take part in meetings and bring reports of the diagnostic-therapeutic pathway to the AMHS clinicians | X | X | Meeting with CAMHS to be informed about transfer options; meeting with AMHS |

| 8 | Patient assessment after transition / monitoring | Partial (request confirmation of successful take-over) | Updates every 3 months | X | X | X | X |

| 9 | Training program | Joint training for CAMHS and AMHS clinicians | X | X | X | X | X |

| 10 | Number of pages | 25 | All: 9; Specific for different centers (25, 9, 9, 5, 5, 8) | 4 | 8 | 23 | 2 |

| 6/9 | 6/9 | 6/9 | 2/9 | 2/9 | 5/9 |

| U.K. | U.S. | Italy | |||

| Dimensions | NICE GUIDELINES | 6 CORE ELEMENTS | SURVEY DATA (42 pediatric and 35 adult services) | PROTOCOLS (n=6) | |

| 1 | Evaluation of transfer need | Transfer to adult mental health services in presence of significant ADHD symptoms or other coexisting conditions that require treatment. Transition planning must be developmentally appropriate. | Establish criteria for identifying transition-aged patients. Conduct regular readiness assessments. | Age and clinical features (comorbidities, severe symptoms, drug treatment). | Most protocols include evaluation of complexity/severity of symptoms. |

| 2 | Early transition planning | From age 13 or 14. Indication to start planning early. Do not use a rigid age threshold, but start transition at a time of relative stability for the young person. | Start discussing it at age 12 and planning it at age 14 to 16. | Most pediatric services start at age 17 or 18; one service starts at 15 and one at 21. | On average 6 months before age 18. Some mention as early as possible after turning 17, only one plans to start at age 14. |

| 3 | Individualized planning | -** | Plan for optimal timing of transfer. Consider tailoring for cultural preferences and health priorities. | Lack of resources makes it hard to plan individual transition pathways. | Evaluating diagnostic picture and relevant social aspects (school, work, autonomy, social integration). |

| 4 | Transition completed by 18 years | Transition should be completed by 18. | NA (Transfer young adults when their condition is as stable as possible). |

Age 15 to 21; median at age 18. | Only around 50% of the protocols foresee completing transition by age 18. |

| 5 | Re-evaluation at school-leaving age | A young person with ADHD receiving treatment and care from CAMHS or pediatric services should be reassessed at school-leaving age to establish the need for continuing treatment into adulthood. | NA | Only two pediatric services consider school, but during transition and not for a subsequent re-evaluation. | NA |

| 6 | Joint CAMHS-AMHS meeting and information sharing | Update all the practitioners involved, including general practitioners. | Build ongoing and collaborative partnership with specialty care clinicians. | 69% of the pediatric services and 60% of the adult services have joint meetings. | All protocols have the indication to program joint meetings. |

| 7 | Family involvement | Co-produce transition policies and strategies with young people and their carers; ask them if the services helped them achieve agreed outcomes and give them feedback about the effect their involvement has had. Ask the young patients how they would like their carers to be involved. | Plan transfer also with parents/caregivers. Elicit parent/caregiver feedback on their experience with the transition. | 67% of the pediatric services and 60% of the adult services have meetings with the families. | Families are regularly updated and often actively involved in the transition planning phase. |

| 8 | Patient assessment after transition / monitoring | Hold annual meetings to review transition planning. Follow up until age 25 when needed (for a minimum of 6 months after transfer). | Integrate with electronic medical records when possible. Contact young adults and caregivers 3 to 6 months after last pediatric visit to confirm attendance at first adult appointment | 9% of the pediatric services and 15% of the adult services plan patients’ monitoring. | One protocol requests confirmation of the successful take-over; one protocol programs updates every 3 months. |

| 9 | Training program | Start and coordinate local training initiatives (including for teachers). Specialist ADHD teams (child and adult psychiatrists, pediatricians, and other child and adult mental health professionals) jointly develop and undertake training programs. | Educate all staff about the practice’s approach to transition. Offer education and resources on needed skills to patients/caregivers. | None. Lack of training often reported as a limit and unmet need. | Only one protocol foresees joint training for pediatric and adult services. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).