Submitted:

04 May 2023

Posted:

05 May 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site, Patient Population, and Specimen Collection

2.2. Xpert® MTB/RIF Assay

2.3. Phenotypic Drug Susceptibility Testing (DST)

2.4. Genotypic DST

2.5. Evaluation and Interpretation of Results

2.6. Spoligotyping

3. Results

3.1. Profile of the Isolates

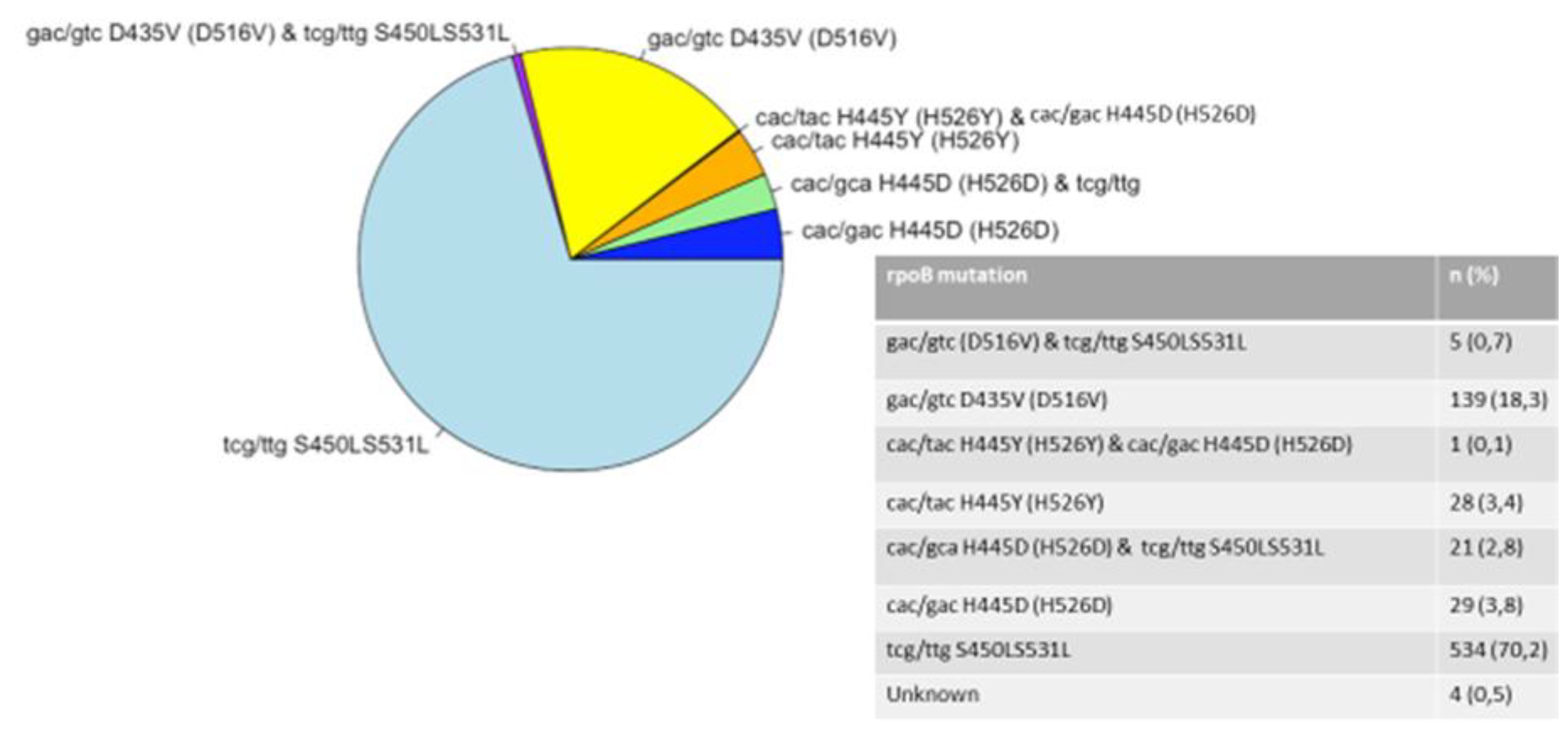

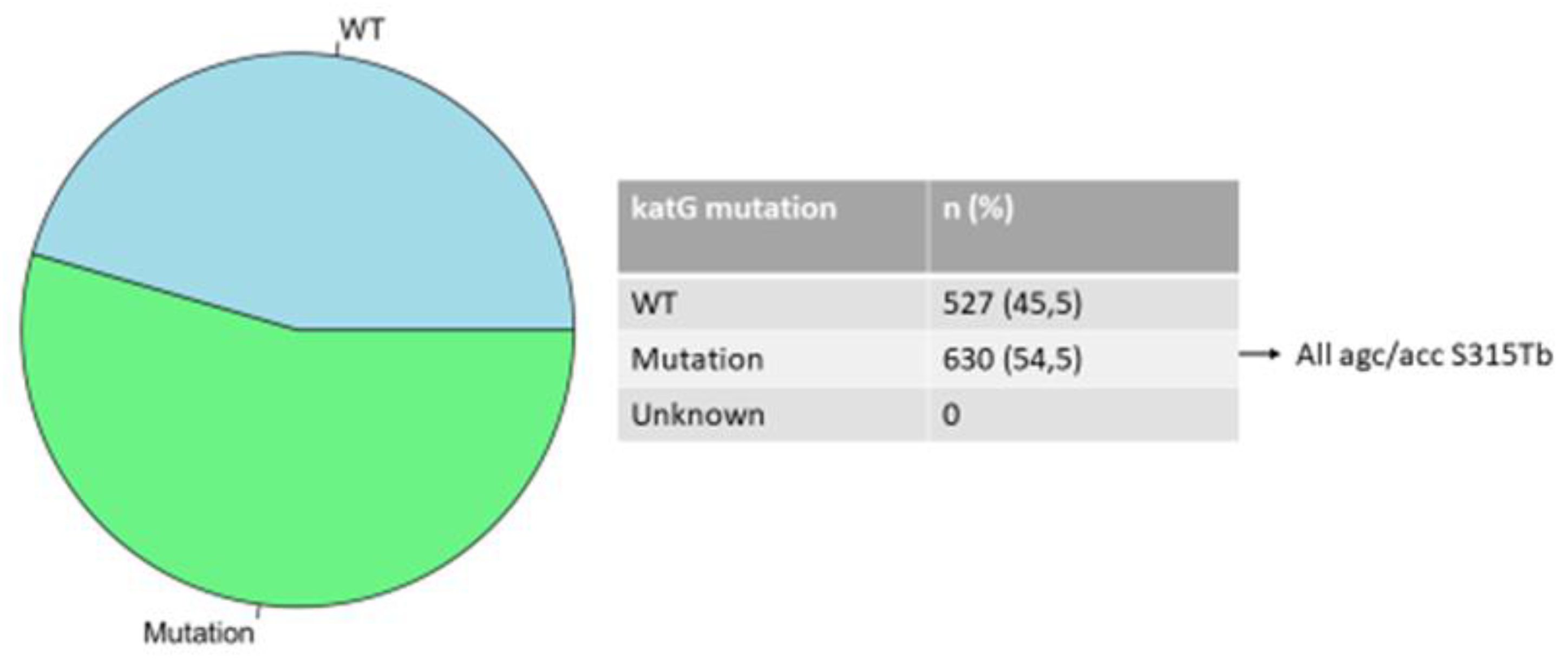

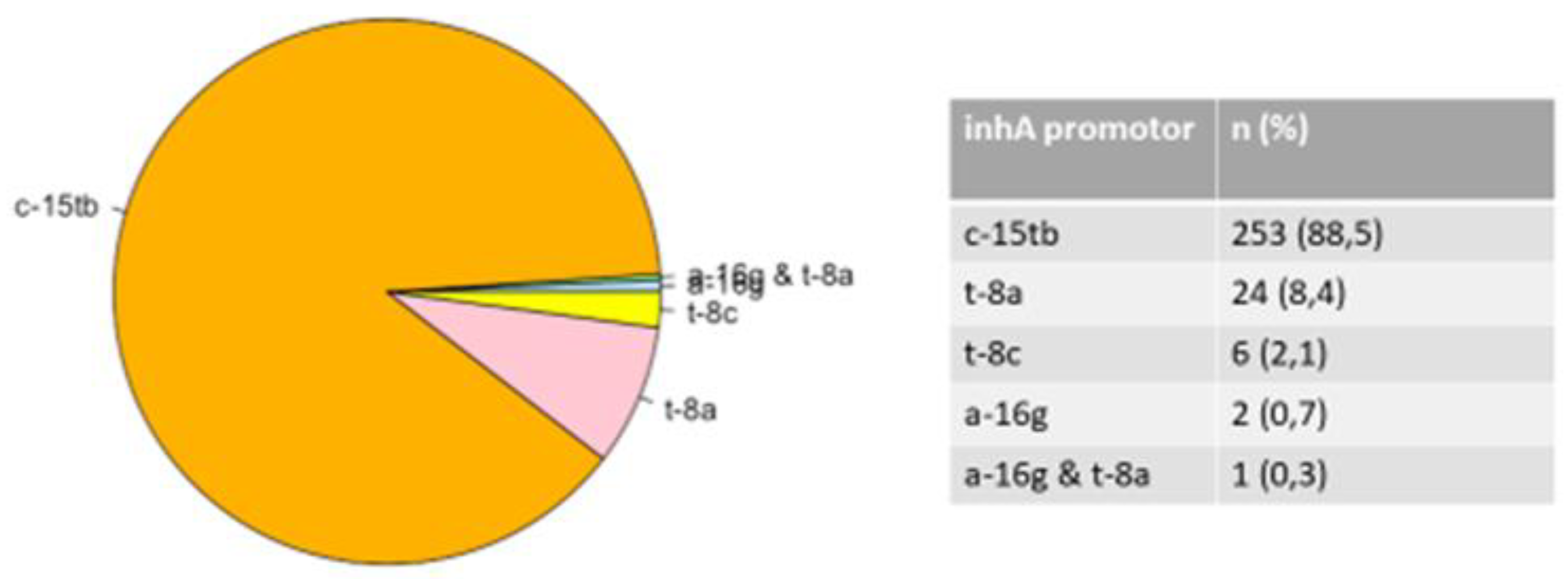

3.2. Mutations in the rpoB, katG, and inhA Genes

3.3. Heteroresistance Mutations

3.4. Spoligotyping

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bwalya, P.; Yamaguchi, T.; Solo, E.S.; Chizimu, J.Y.; Mbulo, G.; Nakajima, C.; Suzuki, Y. Characterization of Mutations Associated with Streptomycin Resistance in Multidrug-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Zambia. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report, 2020 World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland, available at https://apps.who.int/ iris/handle/10665/336069 [accessed August 6, 2022].

- Statistics South Africa. Mortality and causes of death in South Africa. Findings from death notification. Pretoria, South Africa. Stats SA’s June 2021 report [accessed 21 January 2022].

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2021: Supplementary material [accessed August 8, 2022].

- Kabir, S.; Junaid, K.; Rehman, A. Variations in rifampicin and isoniazid resistance associated genetic mutations among drug naïve and recurrence cases of pulmonary tuberculosis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 103, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libiseller-Egger, J.; Phelan, J.; Campino, S.; Mohareb, F.; Clark, T.G. Robust detection of point mutations involved in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the presence of co-occurrent resistance markers. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1008518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Liu, H.; Li, M.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Z.; Wan, K.; Li, G.; Guan, C-x. Genomic Analysis Identifies Mutations Concerning Drug-Resistance and Beijing Genotype in Multidrug-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolated From China. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitso, L.; Potgieter, S.; Van der Spoel van Dijk, A. Prevalence of isoniazid resistance-conferring mutations associated with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Free State Province, South Africa. S Afr. Med. J. 2019, 109, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solo, E.S.; Nakajima, C.; Kaile, T.; Bwalya, P.; Mbulo, G.; Fukushima, Y.; Chila, S.; Kapata, N.; Shah, Y.; Suzuki, Y. Mutations in rpoB and katG genes and the inhA operon in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Zambia. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Res. 2020, 22, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diriba, G.; Kebede, A.; Tola, H.H.; Alemu, A.; Yenew, B.; Moga, S.; Addise, D.; Mohammed, Z.; Getahun, M.; Fantahun, M.; Tadesse, M. Utility of line probe assay in detecting drug resistance and the associated mutations in patients with extra pulmonary tuberculosis in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 2022, 10, 20503121221098241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valafar, S.J. Systematic review of mutations associated with isoniazid resistance points to continuing evolution and subsequent evasion of molecular detection, and potential for emergence of multidrug resistance in clinical strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents. Chem. 2021, 65, e02091–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, X.; Wu, X.; Li, S.; Liu, B.; Rajaofera, M.J.; Zeng, Y.; Dong, S.; Bei, Z.; Pei, H.; Xia, Q. Prevalence and molecular characteristics of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Hainan, China: From 2014 to 2019. BMC. Microbiol. 2021, 21, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodmer, T.; Ströhle, A. Diagnosing pulmonary tuberculosis with the Xpert MTB/RIF test. J.Vis. Exp. 2012, 62, e3547. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The impact of the roll-out of rapid molecular diagnostic testing for tuberculosis on empirical treatment in Cape Town, South Africa, Bulletin. WHO 2017, 95, 545–608. [Google Scholar]

- Hain Lifescience. Company history and product releases. 2016, http://www.hain-lifescience.de/en/company/history.html. (Accessed 11 February 2021).

- Ogari, C.O.; Nyamache, A.K.; Nonoh, J.; Amukoye, E. Prevalence and detection of drug resistant mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis among drug naïve patients in Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couvin, D.; David, A.; Zozio, T.; Rastogi, N. Macro-geographical specificities of the prevailing tuberculosis epidemic as seen through SITVIT2, an updated version of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotyping database. Infect. Genet.Evol. 2019, 72, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhembe, N.L.; Green, E. Characterization of mutations in the rpoB gene conferring rifampicin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolated from lymph nodes of slaughtered cattle from South Africa. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2020, 51, 1919–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otchere, I.D.; Asante-Poku, A.; Osei-Wusu, S.; Baddoo, A.; Sarpong, E.; Ganiyu, A.H.; Aboagye, S.Y.; Forson, A.; Bonsu, F.; Yahayah, A.I.; Koram, K. Detection and characterization of drug-resistant conferring genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: A prospective study in two distant regions of Ghana. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2016, 99, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Z. Analysis on Drug-Resistance-Associated Mutations among Multidrug-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis Isolates in China. Antibiotics. 2021, 10, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakova, J.; Sovkhozova, N.; Vinnikov, D.; Goncharova, Z.; Talaibekova, E.; Aldasheva, N.; Aldashev, A. Mutations of rpoB, katG, inhA and ahp genes in rifampicin and isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Kyrgyz Republic. BMC Microbiol. 2018, 18, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.K.; Rahman, A.; Ather, M.F.; Ahmed, T.; Rahman, S.M.; Ahmed, S.; Banu, S. Distribution and frequency of rpoB mutations detected by Xpert MTB/RIF assay among Beijing and non-Beijing rifampicin resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Bangladesh. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meftahi, N.; Namouchi, A.; Mhenni, B.; Brandis, G.; Hughes, D.; Mardassi, H. Evidence for the critical role of a secondary site rpoB mutation in the compensatory evolution and successful transmission of an MDR tuberculosis outbreak strain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Stead, M.C.; Nicol, M.P.; Segal, H. Rapid genotypic assays to identify drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in South Africa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 63, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssengooba, W.; Meehan, C.J.; Lukoye, D.; Kasule, G.W.; Musisi, K.; Joloba, M.L.; Cobelens, F.G.; de Jong, B.C. Whole genome sequencing to complement tuberculosis drug resistance surveys in Uganda. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 40, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvato, R.S.; Schiefelbein, S.; Barcellos, R.B.; Praetzel, B.M.; Anusca, I.S.; Esteves, L.S.; Halon, M.L.; Unis, G.; Dias, C.F.; Miranda, S.S.; de Almeida, I.N. Molecular characterisation of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from a high-burden tuberculosis state in Brazil. Epidemiol. Infec. 2019, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Tajbakhsh, A.; Ghasemi, F.; Mirbagheri, S.Z.; Heravi, M.M.; Rezaee, M.; Meshkat, Z. Investigation of the rpoB mutations causing rifampin resistance by rapid screening in Mycobacterium tuberculosis in North-East of Iran. Iran. J. Pathol. 2018, 13, 429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bollela, V.R. , Namburete, E.I.; Feliciano, C.S.; Macheque, D.; Harrison, L.H.; Caminero, J.A. Detection of katG and inhA mutations to guide isoniazid and ethionamide use for drug-resistant tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2016, 20, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verza, M.; Scheffer, M.C.; Salvato, R.S.; Schorner, M.A.; Barazzetti, F.H.; Machado, H.D.; Medeiros, T.F.; Rovaris, D.B.; Portugal, I.; Viveiros, M.; Perdigão, J. Genomic epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Santa Catarina, Southern Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagielski, T.; Grzeszczuk, M.; Kamiński, M.; Roeske, K.; Napiórkowska, A.; Stachowiak, R.; Augustynowicz-Kopeć, E.; Zwolska, Z.; Bielecki, J. Identification and analysis of mutations in the katG gene in multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical isolates. Adv. Resp. Med. 2013, 81, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abanda, N.N.; Djieugoué, J.Y.; Lim, E.; Pefura-Yone, E.W.; Mbacham, W.; Vernet, G.; Penlap, V.M.; Eyangoh, S.I.; Taylor, D.W.; Leke, R.G. Diagnostic accuracy and usefulness of the Genotype MTBDRplus assay in diagnosing multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Cameroon: A cross-sectional study. BMC infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.T.; Tai, C.H.; Li, C.R.; Lin, C.F.; Shi, Z.Y. The mutations of katG and inhA genes of isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2015, 48, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenpak, R.; Santimaleeworagun, W.; Suwanpimolkul, G.; Manosuthi, W.; Kongsanan, P.; Petsong, S.; Puttilerpong, C. Association between the phenotype and genotype of isoniazid resistance among Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Thailand. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, F.; Moghim, S.; Farzaneh, S.; Fazeli, H.; Salehi, M.; Esfahani, B.N. Significance of the coexistence of non-codon 315 katG, inhA, and oxyR-ahpC intergenic gene mutations among isoniazid-resistant and multidrug-resistant isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A report of novel mutations. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2022, 116, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, B.; Beer, J.; Emmrich, F.; Sack, U.; Rodloff, A.C. Analysis of gene mutations associated with isoniazid, rifampicin and ethambutol resistance among Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gliddon, H.D.; Frampton, D.; Munsamy, V.; Heaney, J.; Pataillot-Meakin, T.; Nastouli, E.; Pym, A.S.; Steyn, A.J.; Pillay, D.; McKendry, R.A. A Rapid Drug Resistance Genotyping Workflow for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Using Targeted Isothermal Amplification and Nanopore Sequencing. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e00610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate, D.; Tedla, Y.; Meressa, D.; Ameni, G. Isoniazid and rifampicin resistance mutations and their effect on second-line anti-tuberculosis treatment. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2014, 18, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lempens, P.; Meehan, P.J.; Vandelannoote, K.; Fissette, K.; de Rijk, P.; Van Deun, A.; Rigouts, L.; de Jong, B.C. Isoniazid resistance levels of Mycobacterium tuberculosis can largely be predicted by high confidence resistance-conferring mutations. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarin, R.; Bhalla, M.; Kumar, G.; Singh, A.; Myneedu, V.P.; Singhal, R. Correlation of inhA mutations and ethionamide susceptibility: Experience from national reference center for tuberculosis. Lung India. 2021, 38, 520–523. [Google Scholar]

- Maitre, T.; Morel, F.; Brossier, F.; Sougakoff, W.; Jaffre, J.; Cheng, S.; Veziris, N.; Aubry, A.; NRC-MyRMA. How a PCR Sequencing Strategy Can Bring New Data to Improve the Diagnosis of Ethionamide Resistance. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, M.; Catanzaro, D.; Catanzaro, A.; Rodwell, T.C. Genetic Mutations Associated with Isoniazid Resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE, 2015, 10, e0119628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann-Thiel, S.; van Ingen, J.; Feldmann, K.; Turaev, L.; Uzakova, G.T.; Murmusaeva, G.; van Soolingen, D.; Hoffmann, H. Mechanisms of heteroresistance to isoniazid and rifampin of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 33, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.S.; Modongo, C.; Baik, Y.; Allender, C.; Lemmer, D.; Colman, R.E.; Engelthaler, D.M.; Warren, R.M.; Zetola, N.M. Mixed Mycobacterium tuberculosis–strain infections are associated with poor treatment outcomes among patients with newly diagnosed tuberculosis, independent of pretreatment heteroresistance. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 218, 1974–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinder, H.; Mieskes, K.T.; Löscher, T. Heteroresistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2001, 5, 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- de Assis Figueredo, L.J.; de Almeida, I.N.; Augusto, C.J.; Soares, V.M.; Suffys, P.N.; da Silva Carvalho, W.; de Miranda, S.S. Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis heteroresistance by genotyping. Int. J. Mycobacteriol. 2020, 9, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Said, H.; Ratabane, J.; Erasmus, L.; Gardee, Y.; Omar, S.; Dreyer, A.; Ismail, F.; Bhyat, Z.; Lebaka, T.; van der Meulen, M.; Gwala, T.; Adelekan, A.; Diallo, K.; Ismail, N. Distribution and Clonality of drug-resistant tuberculosis in South Africa. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokrousov, I.; Ly, H.M.; Otten, T.; Lan, N.N.; Vyshnevskyi, B.; Hoffner, S.; Narvskaya, O. Origin and primary dispersal of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype: Clues from human phylogeography. Genome Res. 2005, 15, 1357–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- María Irene, C.C.; Juan Germán, R.C.; Gamaliel, L.L.; Dulce Adriana, M.E.; Estela Isabel, B.; Brenda Nohemí, M.C.; Payan Jorge, B.; Zyanya Lucía, Z.B.; Myriam, B.D.; Adrian, O.L.; Martha Isabel, M. Profiling the immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing family infection: A perspective from the transcriptome. Virulence 2021, 12, 1689–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmakar, M.; Trauer, J.M.; Ascher, D.B.; Denholm, J.T. ; Hyper transmission of Beijing lineage Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2019, 79, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguga-Phasha, N.T.; Munyai, N.S.; Mashinya, F.; Makgatho, M.E.; Mbajiorgu, E.F. Genetic diversity and distribution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes in Limpopo, South Africa. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihota, V.N.; Niehaus, A.; Streicher, E.M.; Wang, X.; Sampson, S.L.; Mason, P.; Källenius, G.; Mfinanga, S.G.; Pillay, M.; Klopper, M.; Kasongo, W. Geospatial distribution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes in Africa. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Soolingen, D.; Qian, L.; De Haas, P.E.; Douglas, J.T.; Traore, H.; Portaels, F.; Qing, H.Z.; Enkhsaikan, D.; Nymadawa, P.; van Embden, J.D. Predominance of a single genotype of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in countries of east Asia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995, 33, 3234–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokam, B.D.; Yeboah-Manu, D.; Amiteye, D.; Asare, P.; Guemdjom, P.W.; Yhiler, N.Y.; Morton, S.N.; Ofori-Yirenkyi, S.; Laryea, R.; Tagoe, R.; Asuquo, A.E. Molecular epidemiology and multidrug resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex from pulmonary tuberculosis patients in the Eastern region of Ghana. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhembe, N.L.; Nwodo, U.U.; Okoh, A.I.; Obi, C.L.; Mabinya, L.V.; Green, E. Clonality and genetic profiles of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Microbiology Open 2019, 8, e00449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Spoel van Dijk, A.; Makhoahle, P.M.; Rigouts, L.; Baba, K. Diverse molecular genotypes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex isolates circulating in the Free State, South Africa. Int. J. Microbiol. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solo, E.S.; Suzuki, Y.; Kaile, T.; Bwalya, P.; Lungu, P.; Chizimu, J.Y.; Shah, Y.; Nakajima, C. Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes and their correlation to multidrug resistance in Lusaka, Zambia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 102, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagonda, T.; Mupfumi, L.; Manzou, R.; Makamure, B.; Tshabalala, M.; Gwanzura, L.; Mason, P.; Mutetwa, R. Prevalence of extensively drug resistant tuberculosis among archived multidrug resistant tuberculosis isolates in Zimbabwe. Tuberc. Res. Treat. 2014, 349141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year of Diagnosis | DR-TB Case n (%) | Annual Heteroresistance Rate n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 385 (33.3) | 37 (9.6) |

| 2019 | 376 (32.5) | 43 (11.4) |

| 2020 | 396 (34.2) | 127 (32.2) |

| Combined Mutation | Number of Isolates (%) | Mutation Regions | Number of Isolates (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| rpoB and katG | 532 (69.9) | rpoB S315L and katG 531ST | 366 (68,8%) |

| rpoB and inhA | 187 (24.6) | rpoB S315L and inhA c-15tb | 171 (91,4%) |

| rpoB S315L and inhA a-16g | 1 (0,5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).