Submitted:

08 April 2023

Posted:

10 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

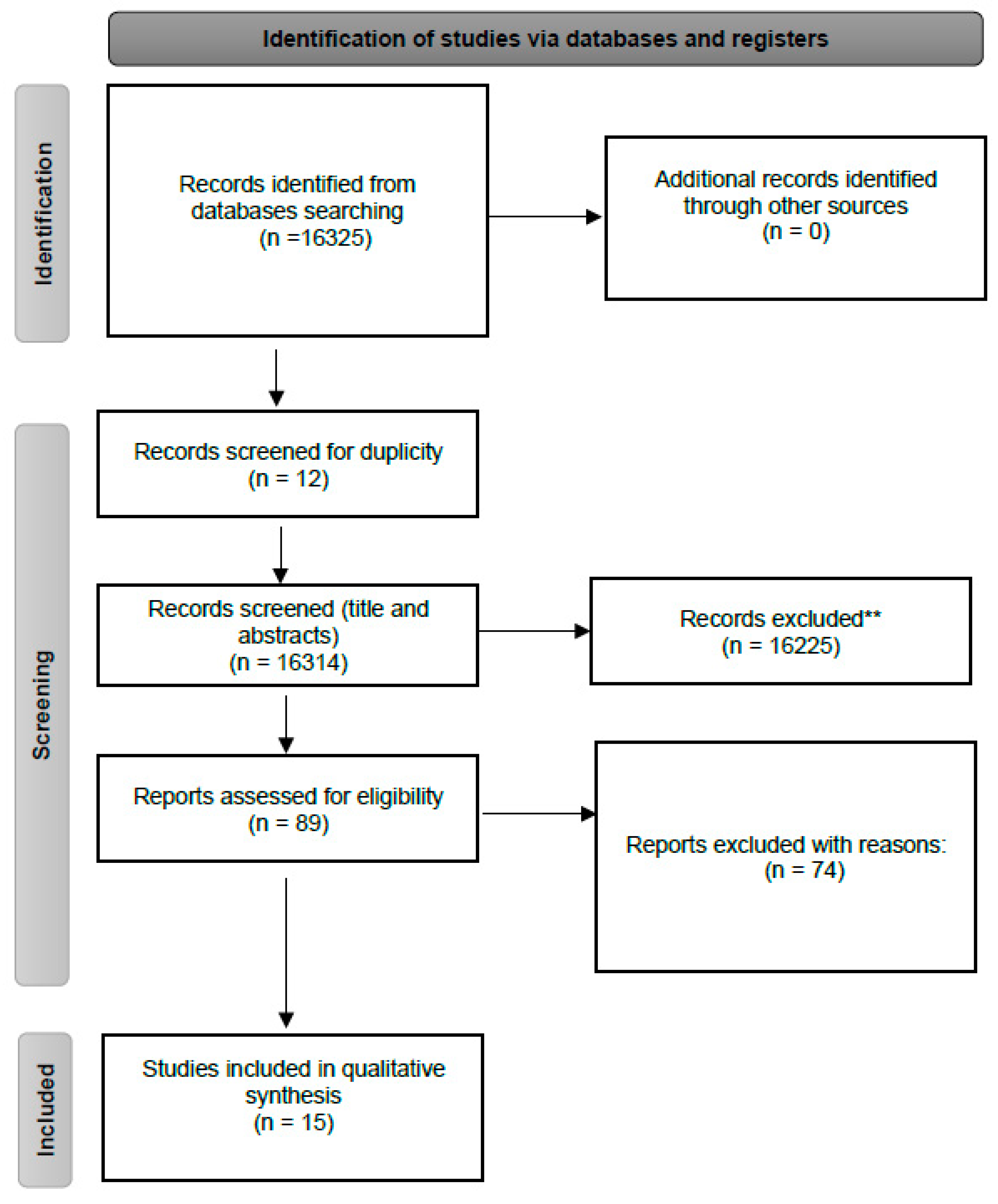

2. Methods

2.1. Literature search

2.2. Eligibility criteria

2.3. Risk of bias

2.4. Data extraction and synthesis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

4.2. Observational Studies

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Statement of Ethics

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olsson, T. , Barcellos, L.F., Alfredsson, L., 2016. Interactions between genetic, lifestyle and environmental risk factors for multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Neurol. [CrossRef]

- Leray, E. , Moreau, T., Fromont, A., Edan, G., 2016. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis. Rev. Neurol. (Paris). [CrossRef]

- Salzer, J. , Hallmans, G., Nyström, M., Stenlund, H., Wadell, G., Sundström, P., 2013. Smoking as a risk factor for multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. [CrossRef]

- Ramanujam, R. , Hedström, A.K., Manouchehrinia, A., Alfredsson, L., Olsson, T., Bottai, M., Hillert, J., 2015. Effect of smoking cessation on multiple sclerosis prognosis. JAMA Neurol. [CrossRef]

- Hedström, A.K. , Sundqvist, E., Bäärnhielm, M., Nordin, N., Hillert, J., Kockum, I., Olsson, T., Alfredsson, L., 2011. Smoking and two human leukocyte antigen genes interact to increase the risk for multiple sclerosis. Brain. [CrossRef]

- Öckinger, J. , Hagemann-Jensen, M., Kullberg, S., Engvall, B., Eklund, A., Grunewald, J., Piehl, F., Olsson, T., Wahlström, J., 2016. T-cell activation and HLA-regulated response to smoking in the deep airways of patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin. Immunol. [CrossRef]

- Rosso, M. , Chitnis, T., 2020. Association between Cigarette Smoking and Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. JAMA Neurol. [CrossRef]

- Öberg, M. , Jaakkola, M.S., Prüss-Üstün, A., Schweizer, C., Woodward, A., 2010. Second-hand smoke: Assessing the environmental burden of disease at national and local levels. WHO Environmental Burden of Disease Series No. 18., World Health Organization.

- Tsai, J. , Homa, D.M., Gentzke, A.S., Mahoney, M., Sharapova, S.R., Sosnoff, C.S., Caron, K.T., Wang, L., Melstrom, P.C., Trivers, K.F., 2018. Exposure to Secondhand Smoke Among Nonsmokers — United States, 1988–2014. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J. , Reeves, B.C., Wells, G., Thuku, M., Hamel, C., Moran, J., Moher, D., Tugwell, P., Welch, V., Kristjansson, E., Henry, D.A., 2017. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. [CrossRef]

- Wells, G. , Shea, B., O’Connell, D., Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M., Tugwell, P., 2012. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. (Available from URL http//www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp). [CrossRef]

- Poorolajal, J. , Bahrami, M., Karami, M., Hooshmand, E., 2017. Effect of smoking on multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis. J. Public Heal. (United Kingdom). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. , Wang, R., Li, Z., Wang, Y., Gao, C., Lv, X., Song, Y., Li, B., 2016. The risk of smoking on multiple sclerosis: A meta-analysis based on 20,626 cases from casecontrol and cohort studies. PeerJ. [CrossRef]

- McKay, K.A. , Jahanfar, S., Duggan, T., Tkachuk, S., Tremlett, H., 2017. Factors associated with onset, relapses or progression in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Neurotoxicology. [CrossRef]

- Degelman, M.L. , Herman, K.M., 2017. Smoking and multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis using the Bradford Hill criteria for causation. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. [CrossRef]

- Oturai, D.B. , Bach Søndergaard, H., Koch-Henriksen, N., Andersen, C., Laursen, J.H., Gustavsen, S., Kristensen, J.T., Magyari, M., Sørensen, P.S., Sellebjerg, F., Thørner, L.W., Ullum, H., Oturai, A.B., 2021. Exposure to passive smoking during adolescence is associated with an increased risk of developing multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. [CrossRef]

- Sakoda, A. , Matsushita, T., Nakamura, Y., Watanabe, M., Shinoda, K., Masaki, K., Isobe, N., Yamasaki, R., Kira, J. ichi, 2020. Environmental risk factors for multiple sclerosis in Japanese people. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. [CrossRef]

- Lavery, A.M. , Collins, B.N., Waldman, A.T., Hart, C.N., Bar-Or, A., Marrie, R.A., Arnold, D., O’Mahony, J., Banwell, B., 2019. The contribution of secondhand tobacco smoke exposure to pediatric multiple sclerosis risk. Mult. Scler. J. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahpour, I. , Nedjat, S., Sahraian, M.A., Mansournia, M.A., Otahal, P., van der Mei, I., 2017. Waterpipe smoking associated with multiple sclerosis: A populationbased incident case–control study. Mult. Scler. [CrossRef]

- Hedström, A.K. , Olsson, T., Alfredsson, L., 2016. Smoking is a major preventable risk factor for multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. [CrossRef]

- Hedström AK, Bäärnhielm M, Olsson T, Alfredsson L, 2011. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke is associated with increased risk for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. [CrossRef]

- Hedström, A.K. , Bomfim, I.L., Barcellos, L.F., Briggs, F., Schaefer, C., Kockum, I., Olsson, T., Alfredsson, L., 2014. Interaction between passive smoking and two HLA genes with regard to multiple sclerosis risk. Int. J. Epidemiol. [CrossRef]

- Toro, J. , Reyes, S., Díaz-Cruz, C., Burbano, L., Cuéllar-Giraldo, D.F., Duque, A., Reyes-Mantilla, M.I., Torres, C., Ríos, J., Rivera, J.S., Cortés-Muñoz, F., Patiño, J., Noriega, D., 2020. Vitamin D and other environmental risk factors in Colombian patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M. , Nabavi, S.M., Fereshtehnejad, S.M., Ansari, I., Zerafatjou, N., Shayegannejad, V., Mohammadianinejad, S.E., Farhoudi, M., Noorian, A., Razazian, N., Abedini, M., Faraji, F., 2016. Risk factors of multiple sclerosis and their relation with disease severity: A cross-sectional study from Iran. Arch. Iran. Med. 2016, 19, 852–860.

- Mandia, D. , Ferraro, O.E., Nosari, G., Montomoli, C., Zardini, E., Bergamaschi, R., 2014. Environmental factors and multiple sclerosis severity: A descriptive study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Ramagopalan, S. V. , Lee, J.D., Yee, I.M., Guimond, C., Traboulsee, A.L., Ebers, G.C., Sadovnick, A.D., 2013. Association of smoking with risk of multiple sclerosis: A population-based study. J. Neurol. [CrossRef]

| Author | Study Design, country, and year | Population | Main findings | Study limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poorolajal et al.[12] | Meta-analysis, Iran, 2017. | - | The study indicated that both former and current smokers are predisposed to develop Multiple Sclerosis (MS). The risk increases proportionally to the number of cigarettes smoked per day. The meta-analysis selected 3 studies that show the association between MS and second-hand smoke (SHS). Among second-hand smokers, the estimated Odds Ratio (OR) of MS was 1.12, when compared with nonsmokers. | (I) Does not identify which studies had the association between MS and second-hand smoke. (II) Data regarding second-hand smokers was not detailly provided. (III) Does not detailly described selected studies. (IV) Limited number of studies in some subgroups. (V) The majority of articles selected were low-quality studies. |

| Zhang et al.[13] | Meta-analysis, China, 2016. | - | The study shows that smoking is an environmental risk to MS. The meta-analysis also identified three studies containing four study populations that show the association between secondhand smoke and MS, reporting an overall OR of 1.24. | The study did not use a technique for assessing the risk of bias in the individual studies included. |

| McKay et al.[14] | Systematic review, Canada, 2017. | - | Three studies selected evaluate the correlation between SHS and MS. Hedström et al. (2011), reported an OR of 1.3 for MS among never-smoker patients who were exposed to SHS. A French study, by Mikaeloff et al. (2007) reported an association between parental smoking and the early onset of MS in their children (OR 2.12), with a higher risk in older children, when compared to younger ones. Gardener et al. (2009) showed that children whose parents used to smoke at home had an increased risk of MS; however, when restricted to the cases that were non-smokers as adults, it was not statistically significant (OR 1.2, CI 0.90-1.5). | The vast literature present in the study limited the full discussion of some papers included, for example the strengths and limitations of each study. |

| Degelman and Herman.[15] | Systematic review, Canada, 2017. | - | Four out of the eight articles analyzed, which cited the correlation between SHS and MS, demonstrated a statistically significant association. Meta-analysis was not performed due to heterogeneity among studies. | (I) Studies included regarding the association between SHS and MS were not described in detail. (II) Quality of study evidence for each outcome was either low or very low. |

| Oturai et al.[16] | Case-control, Denmark, 2021. | N = 2,589. First cohort analyzed was composed by never-smokers (cigarettes), with 342 cases and 590 controls. The second was composed by individuals who started cigarette smoking above the age of 19, with 577 cases and 1,080 controls. | The association between exposure to SHS during adolescence (10-19 years of age) and MS was evaluated. In males, SHS exposure was not correlated to MS in neveractive smoking subjects. However, for those who became cigarette smokers in adulthood, previous SHS exposure history showed up with an OR of 1.593 for MS. SHS exposure in female neveractive smoking subjects demonstrated an OR of 1.43. There was no correlation between SHS in adolescence and MS in female patients that became active smokers after the age of 19 years. | (I) Selection of blood donors as controls. (II) Recall bias may be present, as subjects were asked about their experience and habits. (III) Authors considered SHS exposure only in the workplace or at home and did not consider the experience in other places, for example while outdoors. |

| Sakoda et al.[17] | Case-control, Japan, 2020. | N = 227. Patients with MS: 103. Controls: 124. | MS patients were evaluated regarding environmental exposure risk factors. A history of exposure to SHS was observed to have a positive correlation with MS, with an OR of 1.31. | (I) Small sample size study. (II) Recall bias may be present, as subjects were asked about their past experience and habits. (III) Cases were hospital-based and at various clinical stages, potentially producing selection bias and heterogeneity between MS subjects (IV) Not possible to distinguish patients exposed to SHS as current smokers, ex-smokers, or never-smokers |

| Lavery et al.[18] | Case-control, United States of America, 2019. | N = 297. All subjects aged less than 16 years; 216 children with monophasic acquired demyelinating syndromes (ADS); 81 children with MS. | The study concluded that SHS exposure was 37% more common in MS, in comparison to monophasic acquired demyelinating syndromes (29.5%); however, it was not an independent factor. When associated with the presence of HLADRB1*15, an OR of 3.7 for MS was reached. | (I) Recall bias may be present, as subjects were asked about their past experience and habits. (II) Authors considered SHS exposure only at home and did not consider the experience in other places, for example while outdoors. |

| Abdollahpour et al.[19] | Case-control, Iran, 2017. | N = 1,604. Subjects with MS: 547; Controls: 1,057. | This article demonstrated that active waterpipe (OR 1.77), cigarette (OR 1.69) or secondhand (OR 1.85) tobacco smoking exposure is associated with increased MS risk. Regarding passive smoking, a much stronger association was found in exposures after the age of 20 years (OR~2.2). | (I) Recall bias may be present, as subjects were asked about their past experience and habits. (II) Authors considered SHS exposure only at home and did not consider the experience in other places, for example while outdoors or workplace. |

| Hedström et al.[20] | Case-control, Sweden, 2016. | N = 7,791. Among cases exposed to SHS: 457 never-smokers; 775 smokers. Among controls exposed to SHS: 1,115 never-smokers; 1,321 smokers. | The study assessed the impact of smoking and SHS on MS risk. The exposure to SHS in neversmokers was associated with the occurrence of MS in a dose-dependent manner, with an obtained OR of 1.1 for 1-20 years of exposure and 1.4 for more than 20 years of exposure | (I) Recall bias may be present, as subjects were asked about their experience and habits. (II) Authors considered SHS exposure only in the workplace or at home and did not consider the experience in other places, for example while outdoors. |

| Hedström et al.[21] | Case-control, Sweden, 2011. | N = 2,330. Patients with MS: 695. Controls: 1,635. All subjects reported that they had never smoked before the year of MS onset. | This case-control study considered the exposure to SHS before the year of MS onset for cases and during the same period in the corresponding controls. Subjects who were exposed to SHS were found to be 30% more susceptible to develop MS. Furthermore, the exposure time was directly correlated with risk, when greater than or equal to 20 years, the obtained OR was 1.8, compared to individuals who had never been exposed. | (I) Recall bias may be present, as subjects were asked about their experience and habits. (II) Authors considered SHS exposure only in the workplace or at home and did not consider the experience in other places, for example while outdoors. |

| Hedström et al.[22] | Case-control, Sweden, 2014. | N = 2,879. All subjects with MS. All subjects were never-smokers. Cases (never-smokers exposed to SHS): 1,311. Controls (never-smokers not exposed to SHS): 1,568. | This study evaluated the development of MS in groups of individuals who carried HLA-DRB1*15 and lacked HLA-A*02, which are genetic conditions that increase the susceptibility of MS (OR of 4.5). These patients presented a 7.7- fold higher chance of developing MS if exposed to SHS when compared to non-smokers never exposed to SHS without these HLA genotypes. | (I) Recall bias may be present, as subjects were asked about their experience and habits. (II) Authors considered SHS exposure only in the workplace or at home and did not consider the experience in other places, for example while outdoors. |

| Toro et al.[23] | Cross-sectional, Colombia, 2020. | N = 174. Subjects with MS: 87. Subjects without MS: 87. | In the analysis, neither cigarette nor SHS history had a statistically significant association with an increased risk for MS. | (I) Recall bias may be present, as subjects were asked about their past experience and habits. (II) No detailed quantitative data on SHS amounts. (III) Subjects were asked about SHS exposure only considering when they were 19-25 years old |

| Abbasi et al.[24] | Cross-sectional, Iran, 2016. | N = 660. All subjects with MS. | From the total of 660 patients with MS included in the study, most were female, with a median age of 37 years, and with relapsing-remitting MS clinical features. The analysis showed no association between SHS and MS severity. | (I) No detailed data on quantitative SHS amount. (II) Recall bias may be present, as subjects were asked about their experience and habits. |

| Mandia et al.[25] | Cross-sectional, Italy, 2014. | N = 131. All subjects with MS. | The study examined factors that may be associated with the evolution of MS. There was no significant correlation between cigarette smoking status or exposure to SHS and the severity of MS. | (I) Small sample size study. (II) Recall bias may be present, as subjects were asked about their past experience and habits. (III) Not possible to distinguish patients exposed to SHS as current smokers, ex-smokers, or never-smokers. (IV) The study only considered the exposure to SHS 12 months prior to data collection. |

| Ramagopalan et al.[26] | Case-control, Canada, 2013. | N = 3,913. MS cases: 3,157. Controls (spouses): 756. | MS cases and spouses were asked about cigarette smoking and SHS exposure. There was no correlation between SHS and MS in never-smoking patients. Exposure to SHS at home presented an OR of 0.87, whereas at the workplace the OR was 0.99. | (I) Recall bias may be present, as subjects were asked about their experience and habits. (II) No quantitative data on SHS amounts. (III) Small control sample, possibly underpowered to detect relevant effects. (IV) Authors considered SHS exposure only in the workplace or at home and did not consider the experience in other places, for example while outdoors. (V) The study did not collect information on paternal smoking. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).