1. Introduction:

The use of digital information electronically transmitted, stored, and obtained to promote health-related activities and services has been encouraged by the world health organization [

1]. As such, novel approaches have been proposed to increase the quality of care and enhance outcomes due to an increased incidence of chronic disorders and difficulties in maintaining adequate screening and follow-up measures [

2,

3]. Digital health and telemedicine can perform various healthcare procedures [

4]. These approaches can significantly enhance the quality of long-distance care, provide patients with suitable preventive and educational options about their disorders, and keep them in touch with their healthcare team in addition to maintaining adequate levels of data privacy [

5,

6]. Digital health can be used for many purposes including educational campaigns and research to further enhance the quality of care.

Moreover, properly applying the approaches of digital health and medical applications can also improve access to high-quality and costly approaches that can improve outcomes [

7,

8]. Mobile and internet healthcare applications and websites have increased recently [

9]. This might be due to increased awareness of the benefits that they offer including easy monitoring of health [

10]. Similar modalities have been reported in developed countries including online systems and databases that monitor patients with chronic diseases while also offering emergency care [

11]. However, the concept of digital healthcare and medical applications within developing countries is still poor [

12,

13]. For instance, an investigation from Libya estimated that 12% of healthcare workers were not familiar with telemedicine, and only 39% had an adequate understanding of digital healthcare modalities [

14].

Attitudes toward the use of digital healthcare and medical applications is markedly affected by individuals’ knowledge and awareness [

14]. There are many reasons for this including the fact that applying these approaches is challenging for individuals in developing countries. These people may have poor training in these modalities and require an introduction to new technologies [

15]. Accordingly, adequate assessment of knowledge and awareness is essential to determine the appropriate plan before planning any interventions. However, there is a dearth of evidence in Saudi Arabia exploring the extent to which the general population has embraced medical apps. Therefore, there was a need to conduct a study to understand the usage of digital health mobile-based applications by the people living in Saudi Arabia.

2. Methods:

2.1. Study design and setting

An analytical cross-sectional study was conducted between October and December 2021 in Saudi Arabia.

2.2. Study population and sampling

All people in Saudi Arabia aged at least 15 years old and having a smart device at the time of data collection were eligible to participate in this study. A snowball approach of sampling was used to identify participants. Any person with a link was urged to send it to a friend(s). Opening the link and filling the questions in the link implied informed consent to all participants.

2.3. Data collection and tool.

Data was collected using a researcher designed survey. A link to the survey was shared by the researchers to all their friends and encouraged to share it with as many people as possible across the country. The sharing of the link was through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn and WhatsApp. A pre-coded pre-tested questionnaire done specifically for this study contains background questions in addition to other close-ended questions that can investigate awareness and attitudes toward digital health and medical applications. The participants had to answer multiple questions including demographic factors and questions related to the study objectives. Five different items on the questionnaire measured the knowledge and awareness of the participants. Questions developed regarding knowledge include the number of medical applications that have been downloaded on the mobile device, how much the participant knows about medical applications, the number of official Saudi authorities’ applications that have been used, and whether they faced any difficulties while completing the data in the application. Awareness questions included whether the subjects had heard of digital health, the number of medical applications on the device, how much they know about smart devices medical applications, whether they have benefited from those applications in medical uses and situations, and whether they agree that using medical applications on a smart device is necessary.

2.4. Data analysis

Data were entered, coded, and processed using Microsoft Excel and the software Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) (Version 23). Descriptive statistics were generated for all variables and Chi-square test was conducted to understand the difference for use of medical apps among participants of selected characteristics. Additionally, a spearman rank correlation was conducted to determine the association between participants’ educational level, number of apps on their devices, and knowledge of smart devices medical apps, a correlation was computed. All statistical tests were considered significant at p < 0.05.

2.5. Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from Almaarefa University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the study, and the collected data was only used for the purposes described in the study objectives.

3. Results:

As indicated in table one, majority of the participants were females (67.1%), aged at least 31 years, and Saudi nationals (90.9%). Most of these participants had completed college level of education (70.5%) and were residing in villa residence type (70.4%) and owned residence status (71.9%). Most of the participants also had a monthly income of between 6,000 and 10,000 (64.9%), did not report having any chronic illnesses (56.5%), were not taking regular medicines (59.1%), and had never faced any medical condition requiring urgent intervention (69.8%).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants.

| Characteristic |

Frequency |

Percent |

| Gender |

|---|

| |

Female |

494 |

67.1 |

| Male |

242 |

32.9 |

| Age |

| |

15-22 years |

110 |

14.9 |

| 23-30 years |

135 |

18.3 |

| 31-38 years |

115 |

15.6 |

| 39-46 years |

138 |

18.8 |

| 47 or older |

238 |

32.3 |

| Education Level |

| |

High school |

175 |

23.8 |

| College |

519 |

70.5 |

| Elementary |

36 |

4.9 |

| Primary |

6 |

.8 |

| Nationality |

| |

Saudi |

669 |

90.9 |

| Non-Saudi |

67 |

9.1 |

| Residence Type |

| |

Villa |

518 |

70.4 |

| Apartment |

150 |

20.4 |

| A floor of three |

68 |

9.2 |

| Residence Status |

| |

Owned |

529 |

71.9 |

| Rented |

207 |

28.1 |

| Monthly Income |

| |

Less 2000 |

60 |

11.3 |

| 2000-5000 |

127 |

23.8 |

| 6000-10000 |

346 |

64.9 |

| Suffer from any chronic diseases or allergies |

| |

Yes |

320 |

43.5 |

| No |

416 |

56.5 |

| Using regular medications |

| |

Yes |

301 |

40.9 |

| No |

435 |

59.1 |

| Faced a medical condition requiring urgent intervention |

| |

Yes |

222 |

30.2 |

| No |

514 |

69.8 |

Table 2 shows the participants’ responses about using medical applications on their smart devices. Majority of the participants had heard of digital health (53.4%) from internet advertisement (24.6%), healthcare workers (15.2%). and family/friends (22.1%). Majority of the participants had at least two medical apps on their smart devices (63.7%). Unfortunately, most (63.5%) of these participants had little knowledge about medical apps on smart devices. Eighty eight percent (88%) of the participants believed that medical apps positively affect the quality of provided health care and that using medical apps to access personal medical data was an appropriate way (89.5%). Most (89%) of the participants have never been in a situation of using medical applications to know the medical history to save an injured person. Participants who believed medical data and medical history were not private information were as many as those who believed it was private information.

To investigate if there was a statistically significant association between participants’ educational level, number of apps on their devices, and knowledge of smart devices medical apps, a correlation was computed. All the data was ordinal; thus, Spearman rank correlation statistic was calculated.

Table 3 shows that one of the pairs of the variable (number of medical apps on device and knowledge about smart devices medical applications) was significantly correlated,

r (507) = .178,

p= .000. The direction of the correlation was positive, meaning that highly educated participants tend to have more knowledge about smart devices medical application and vice versa.

To determine whether there was a significant difference on using medical apps among participants of differing characteristics, a Chi-square test was run.

Table 4 shows that being in a situation of using medical applications to know the medical history for the sake of saving an injured person was statistically significant. The participants who had never been in a situation of using medical applications to know the medical history for the sake of saving an injured person used the medical apps on their smart devices less than their counterparts who had been in such a situation (

X2= 4.97

, df=1

, N=736

, p=.026).

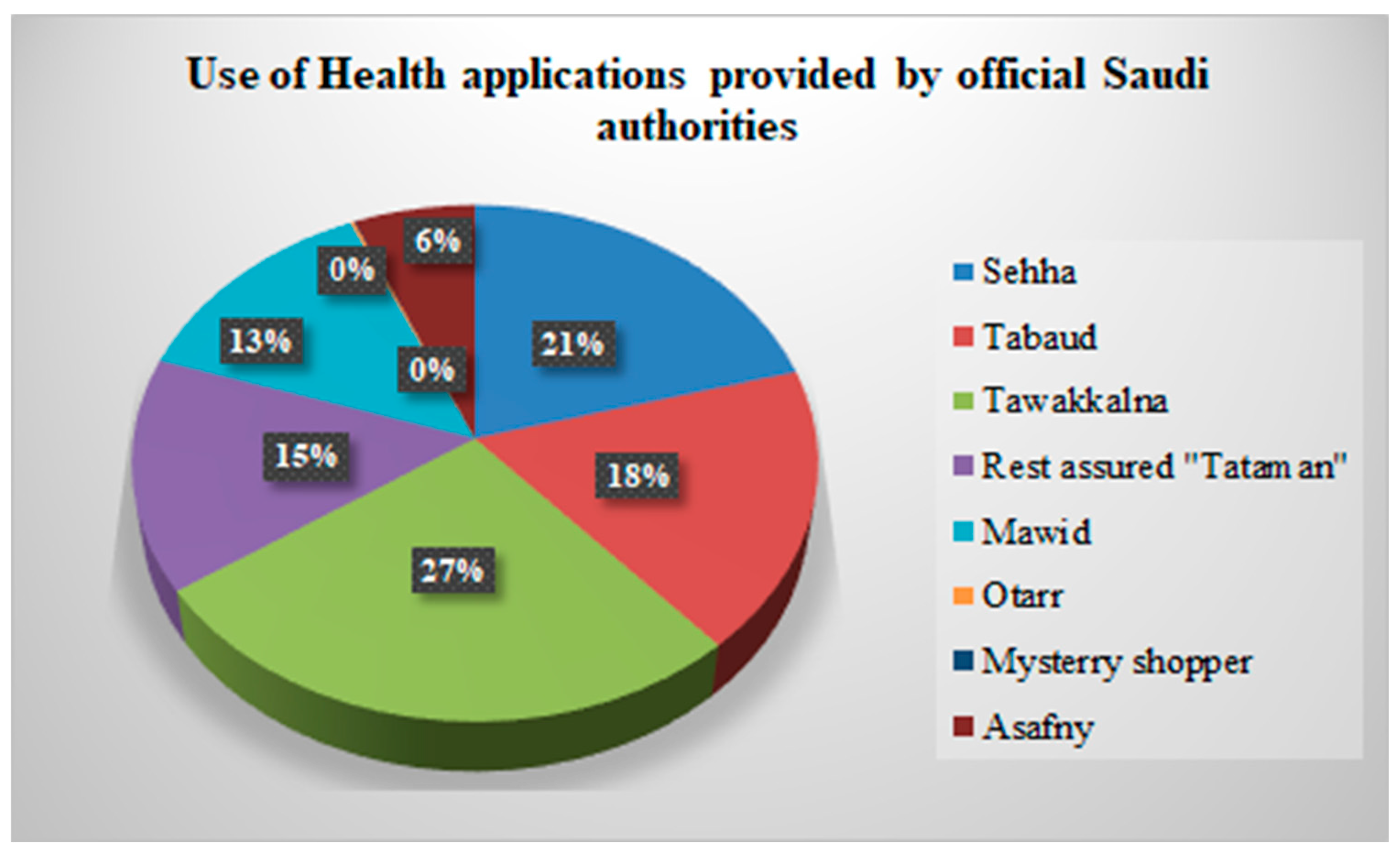

As shown in

Figure 1, majority of the participants had “Tawakkalna” application on their smart devices (27%), followed by “Sehha” with (21%).

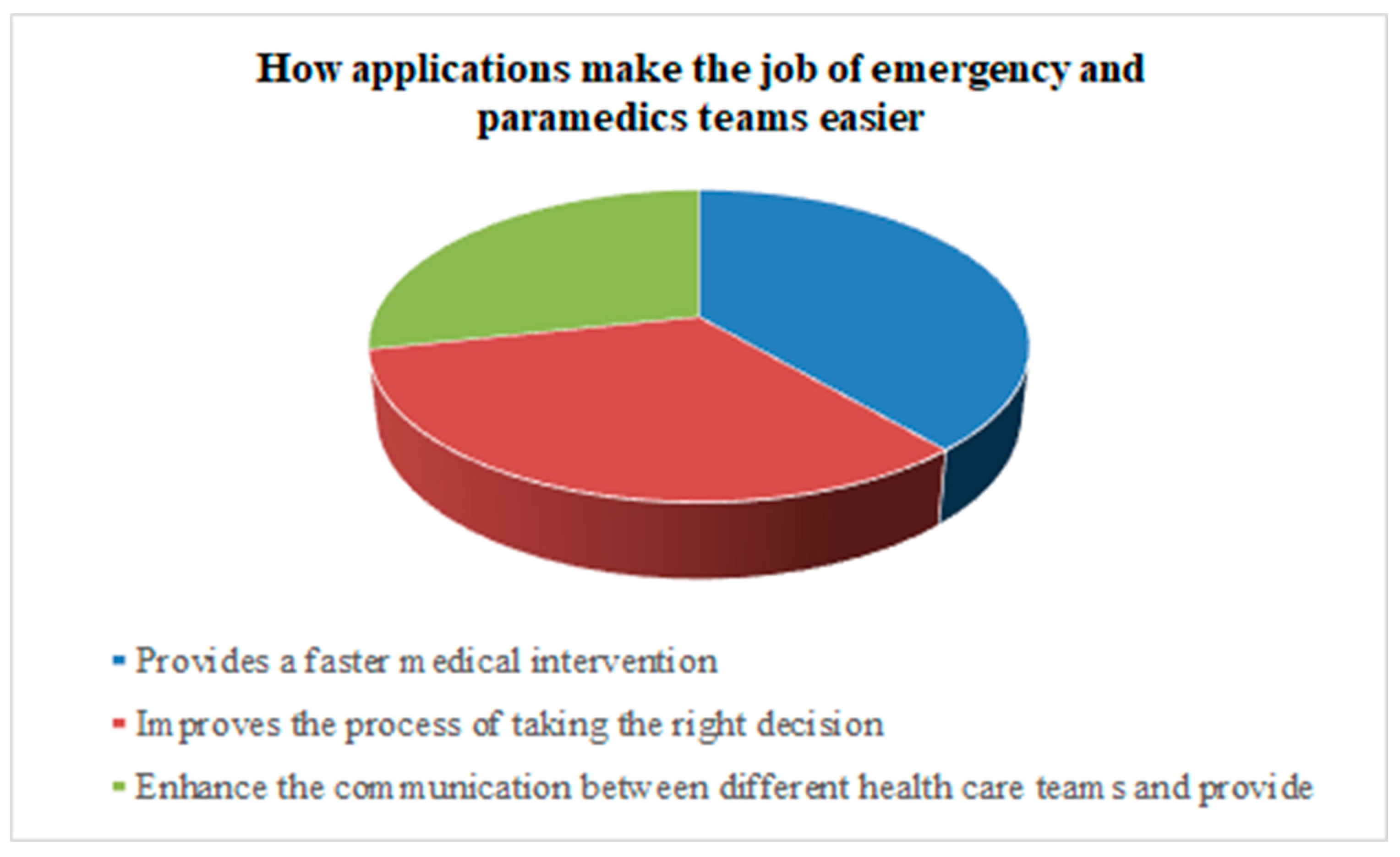

As far as benefits of using medical applications are concerned (

Figure 2), most of the participants reported improving the process of taking the right decision followed by providing faster medical intervention and enhancing communication between different health care teams.

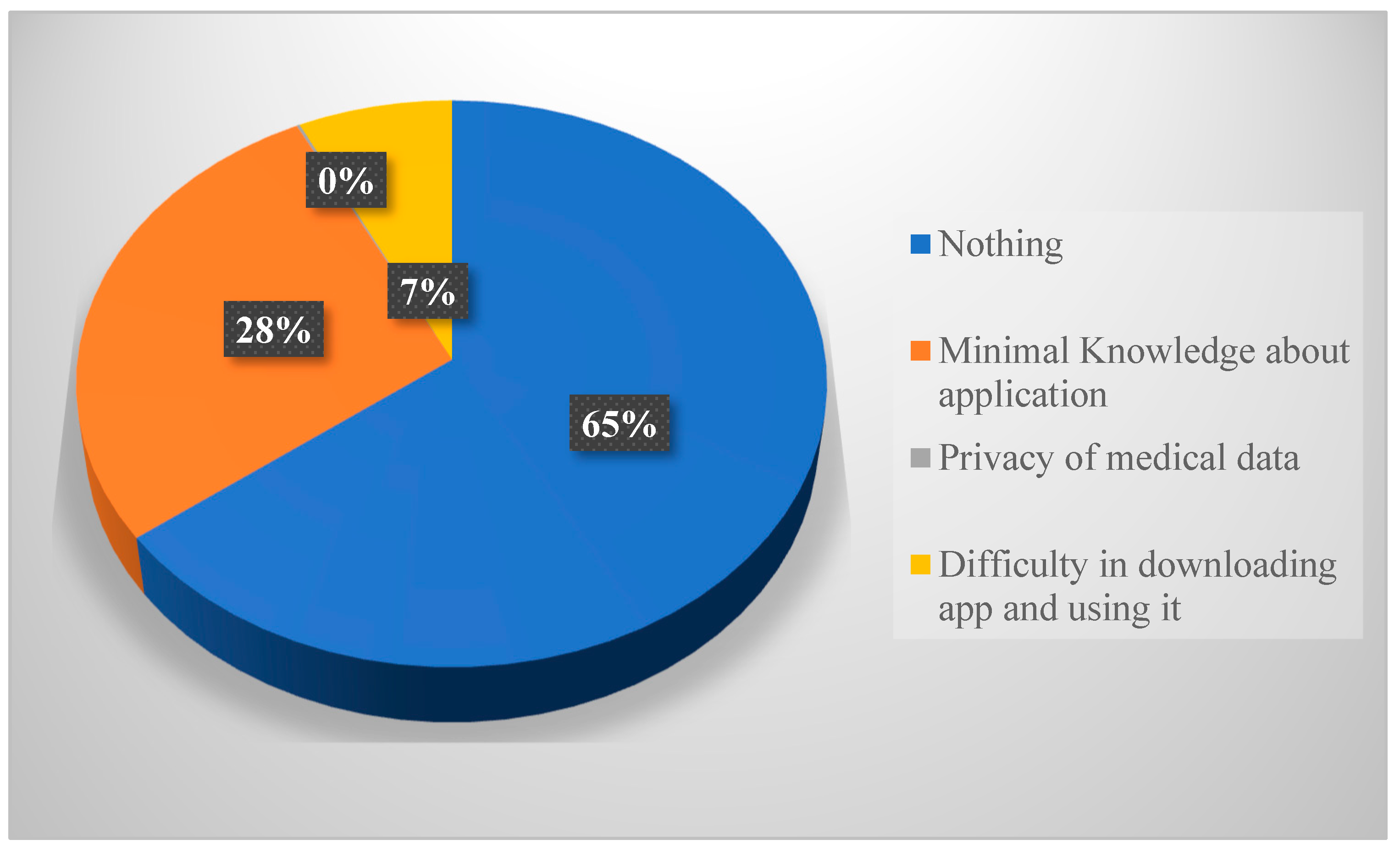

While majority of the participants reported having no barrier to the use of medical applications on their smart devices (

Figure 3), the common three barriers reported by participants were minimal knowledge about the application, difficulty in downloading the application and using it as well as privacy related to medical data.

4. Discussion:

As electronic health records gradually replace paper-based methods in healthcare, the manifestation of such changes needs to be assessed in Saudi Arabia. While evidence shows that Saudi Arabia has adopted electronic health records [

16,

17,

18], the usability of such records has not been widely studied. Yet, electronic health records have been found to increase healthcare quality and patient safety by making patient medical information readily available and accessible to any authorized user. While electronic(e) health, digital health, and mobile (m) health can be used interchangeably, digital health takes on several versions including being available on smartphones, tablets, smartwatches, and health facility computerized systems [

18]. In this study, most participants had at least a medical app on their smart devices. In a previous study, Atallah et al. reported similar findings about mentally challenged people [

19]; each of them had between one and two applications on their phones. Implying that a reasonable number of Saudis have embraced the government’s call to the utilization of electronic health. In 2018, the Saudi government launched digital health in the country and urged all healthcare facilities and practitioners to embrace the new technology-oriented care [

20]. While huge strides have been observed in this regard, the progress warrants the local people to embrace the move as well.

The majority of the participants in this study largely believed that the medical apps were good. However, they reported having little knowledge about the use of these medical apps. The knowledge of medical applications was affected by the education level of the participants. The study findings show that the participants who were more educated were more likely to understand medical apps compared to those who were less educated. On the contrary, the majority of the participants were above college-level education, yet, with little knowledge. Implying that other factors could have been responsible for this observation that the study did not well explore.

It’s important to note that most of the participants had never suffered from any chronic illnesses, were not taking regular medicines, never faced a medical condition requiring urgent intervention, and had never been in a situation of using medical applications to know the medical history for the sake of saving an injured person. Subsequently, the correlation statistic indicated that the participants who had never been in a situation of using medical applications to know the medical history for the sake of saving an injured person used the medical apps on their smart devices less than their counterparts who had been in such a situation. As such, while it was important to understand digital health considering the general population, it is also important to note that some of the asked questions created a limitation to this study. The respondents had not much knowledge of the asked subject areas. Contrastingly, other studies have indicated that even among health workers, medical app utilization is low due to personal reasons [

21]. Some people are still locked up in the traditional life of no smart devices and even when they get smart devices they are not interested in the functioning of the medical apps on such devices. Therefore, digital uptake among health workers needs to be enforced first before scaling it up across the general population.

This study, however, showed that the participants were financially stable enough to own smart devices that can accommodate medical applications. The majority of the participants were residing in owned apartments and of Villa type and their monthly income level was between SAR 6,000 and SAR 10,000. As such, one would be moved to conclude that they can afford smart devices and the costs involved with the digital health approach.

The importance of digital health records has been demonstrated by many participants. Participants indicated that digital health improves the process of taking the right decision, provides a faster medical intervention, and enhances communication between different healthcare teams. Similarly, studies elsewhere have pointed to digital health being of benefit to both patients and healthcare workers [

22,

23]. For the Saudi Arabia government, this current understanding is good and shows an upward trend toward the desired full penetration of digital health in the country which was shown to be very low in 2019 [

23]. As full medical application penetration is realized, Saudi Arabia will be just like other developed countries that largely rely on digital health implementation for quick interactions between health workers and patients or in even emergency situations where urgent help is needed, and the doctor or physician might not be close. In some instances, patients’ conditions are not so critical to attract physical movement to a health facility. For example, patients with chronic conditions can be supported electronically from their places of residence through their phones.

While the majority of the participants had never heard about digital health, their major source of information was the internet, and less health worker communication. Given the fact that the Saudi government has intentionally financed the implementation of e-health [

24], it should as well widen the health communication to the population (specifically to non-health workers) so that people are aware of the importance and the use of digital health as well. However, as this recommendation suffices, evidence also shows that the knowledge of digital health among health workers is lacking [

24]. Hence, wholistic equipping of Saudi people on digital health is important and urgently needed.

Most participants had Tawakkalna and Sehha medical apps on their digital devices. The high use of these two apps could be linked to the fact that Sehha app was the seminal application in 2018 as the Saudi government was launching telemedicine [

20]. Tawakkalna app was later introduced in 2020 as the main contact tracing app for Covid-19-related cases. Contrastingly, in a very recent study, these two apps received the least usability ratings regarding Covid-19 [

16]. The respondents reported facing several barriers ranging from increased battery drain, and lack of privacy, to technical issues [

16]. Nevertheless, it’s important to observe that the use of medical apps in Saudi Arabia is on the rise and requires slight enforcement.

The commonly reported barriers to digital health were knowledge about application use, the privacy of medical data, and difficulty downloading the apps. The same barriers have been reported previously in Saudi Arabia. Aljohani and Chandra assert that for Saudi Arabia to succeed fully in digital health, the apps should be reliable enough to provide accurate and up-to-date data [

23]. Additionally, Aljohani and Chandra put forward social influence as a barrier to digital health; the authors asserted that some health workers and the Saudi population exhibit a culture of boredom pertaining to digital health [

23], hence, a need to address it for the success of digital health promotion in the country. An additional barrier that could be worth paying attention to is the language in which most apps have been introduced. While Arabic is largely spoken in Saudi, evidence shows that most of the apps have been introduced in English [

25], creating a language barrier for would-be users. It’s, therefore, a mandate of the Saudi government to address the barriers above if digital health is to blossom in Saudi Arabia.

The world health organization asserts that embracing digital health at both local and distant levels would tremendously address and enhance the struggling healthcare systems in developing countries that have trained doctors, clinicians, equipment, and infrastructure constraints [

1]. It is believed that digital health closes the rural-urban divide in many countries [

26].

5. Conclusion:

This study has shown that digital health among Saudis has several benefits that are on both the side of healthcare and personal health. While many participants already have medical apps on their smart devices, the current study findings indicate that there is a knowledge gap pertaining to their use. Other non-knowledge-related barriers to medical app utilization exist that make people hesitant to both have apps on their smart devices and uncomfortable using them. Given the fact that the Saudi government was at the center of the initiation of digital health in Saudi Arabia, it has an additional role in addressing the barriers hindering the understanding and use of medical apps. This study had several limitations as indicated throughout the discussion that makes it inappropriate to generalize the results to other study settings. Additionally, further research is needed to fully evaluate the progress on digital health uptake among healthcare workers and how the healthcare workers are motivating the patients or potential patients to embrace it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.; methodology, N.A., Y.A. and N.Z.A.; software, K.A., B.A., N.A., A.M.A. and N.Z.A.; validation, N.A., Y.A., N.A. and N.Z.A.; formal analysis, N.A., Y.A.,N.A., and N.Z.A.; investigation, A.M.A. and N.Z.A.; resources, N.A., Y.A., K.A., B.A. and N.A.; data curation, N.Z.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A., Y.A., K.A., B.A., N.A., A.M.A. and N.Z.A.; writ-ing—review and editing, A.M.A. and N.Z.A.; visualization, N.Z.A.; supervision, N.A.; project administration, N.A. ; funding acquisition, N.A., Y.A., K.A., B.A. and N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research participants were re-viewed and approved by the Local Research and Ethical Committee of AlMaarefa University numbered (3/211) with (approval number: ECM#2023-803).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in this analysis can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our study participants who humbly responded to our all questions and gave their valuable time.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Taibah1, H.; Arlikatti, S.; and Delgrosso, B. Advancing e-health in Saudi Arabia: calling for smart village initiatives. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment. 249. Available on https://www.witpress.com/elibrary/wit-transactions-on-ecology-and-the-environment/249/37877. Accessed on April 5, 2023.

- Sánchez, A., et al., Integrated Care Program for Older Adults: Analysis and Improvement. J Nutr Health Aging, 2017. 21(8): p. 867-873.

- Harper, S., The capacity of social security and health care institutions to adapt to an ageing world. International Social Security Review, 2010. 63(3-4): p. 177-196. [CrossRef]

- Stroetmann, K., et al., How can telehealth help in the provision of integrated care? 2010.

- Wootton, R., Telemedicine. BMJ, 2001. 323(7312): p. 557-560.

- Abbott, P.A., and Y. Liu, A scoping review of telehealth. Yearb Med Inform, 2013. 8: p. 51-8.

- Leu, D. and C. Kinzer, The convergence of literacy instruction with networked technologies for information and communication. Reading Research Quarterly, 2000. 35. [CrossRef]

- Saliba, V., et al., Telemedicine across borders: a systematic review of factors that hinder or support implementation. Int J Med Inform, 2012. 81(12): p. 793-809. [CrossRef]

- Krebs, P. and D.T. Duncan, Health app use among us mobile phone owners: a national survey. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 2015. 3(4): p. e101. [CrossRef]

- McGillicuddy, J.W., et al., Patient attitudes toward mobile phone-based health monitoring: questionnaire study among kidney transplant recipients. J Med Internet Res, 2013. 15(1): p. e6. [CrossRef]

- Lluch, M., Incentives for telehealthcare deployment that support integrated care: A comparative analysis across eight European countries. International Journal of Integrated Care, 2013. 13: p. e042. [CrossRef]

- Adeloye, D., et al., Assessing the coverage of e-health services in sub-Saharan Africa. a systematic review and analysis. Methods Inf Med, 2017. 56(3): p. 189-199. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, L., et al., Knowledge and perception of health workers towards tele-medicine application in a new teaching hospital in Lagos. Scientific Research and Essays, 2007. 2: p. 016-019.

- El Gatit, A.M., et al., Effects of an awareness symposium on perception of Libyan physicians regarding telemedicine. East Mediterr Health J, 2008. 14(4): p. 926-30.

- Alkhormi, A.H.; Mahfouz, M.S.; Alshahrani, N.Z.; Hummadi, A.; Hakami, W.A.; Alattas, D.H.; Alhafaf, H.Q.; Kardly, L.E.; Mashhoor, M.A. Psychological Health and Diabetes Self-Management among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes during COVID-19 in the Southwest of Saudi Arabia. Medicina 2022, 58, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghareeb, M.1, Albesher, S.A., and Asif, A. Studying users’ perceptions of COVID-19 mobile applications in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 2023, 15, 956. [CrossRef]

- Noor, A. The Utilization of E-Health in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET).2019. 6-9. Available on https://www.irjet.net/archives/V6/i9/IRJET-V6I9187.pdf. Accessed on April 5, 2023.

- Jadi. A. Mobile health services in Saudi Arabia-challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications.2020 11, (4). [CrossRef]

- Atallah, N., Khalifa, M., El Metwally, A., Househ, M. The prevalence and usage of mobile health applications among mental health patients in Saudi Arabia. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2018. 156:163-168. [CrossRef]

- Aldhahir, M.A. Current Knowledge, satisfaction, and use of E-Health mobile application (Seha) among the general population of Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2022:15 667–678. [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, M.S. et al. Healthcare Providers’ Perception and Barriers Concerning the Use of Telehealth Applications in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1527. [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, N.Z.; Ridda, I.; Rashid, H.; Alzahrani, F.; Othman, L.M.B.; Alzaydani, H.A. Willingness of Saudi Adults to Receive a COVID-19 Vaccine Booster Dose. Sustainability 2023, 15, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, N. Adoption of M-Health applications: The Saudi Arabian healthcare perspectives. Australasian Conference on Information Systems. Available on https://acis2019.io/pdfs/ACIS2019_PaperFIN_045.pdf. Accessed on April 5, 2023. 5 April.

- Aleisa, M.A.; Abdullah, N.S.; Alqahtani, A.A.A.; Aleisa, J.A.J.; Algethami, M.R.; Alshahrani, N.Z. Association between Alexithymia and Depression among King Khalid University Medical Students: An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, U.T, et al. E-health and its Transformation of Healthcare Delivery System in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences. 2018, 7(5): 76-82. Available on https://www.ijmrhs.com/medical-research/ehealth-and-its-transformation-of-healthcare-delivery-system-in-makkah-saudi-arabia.pdf. Accessed on April 5, 2023.

- World Health Organization, eHealth conversations: using information management, dialogue, and knowledge exchange to move toward universal access to health. Available at http://iris.paho.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/28392/9789275118283_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed on: 5 April. 2023.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).