Submitted:

11 April 2023

Posted:

11 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gamma attenuation theory

2.2. Calculation model

2.3. Experiment

2.2.1. Preparation of W/EP Samples

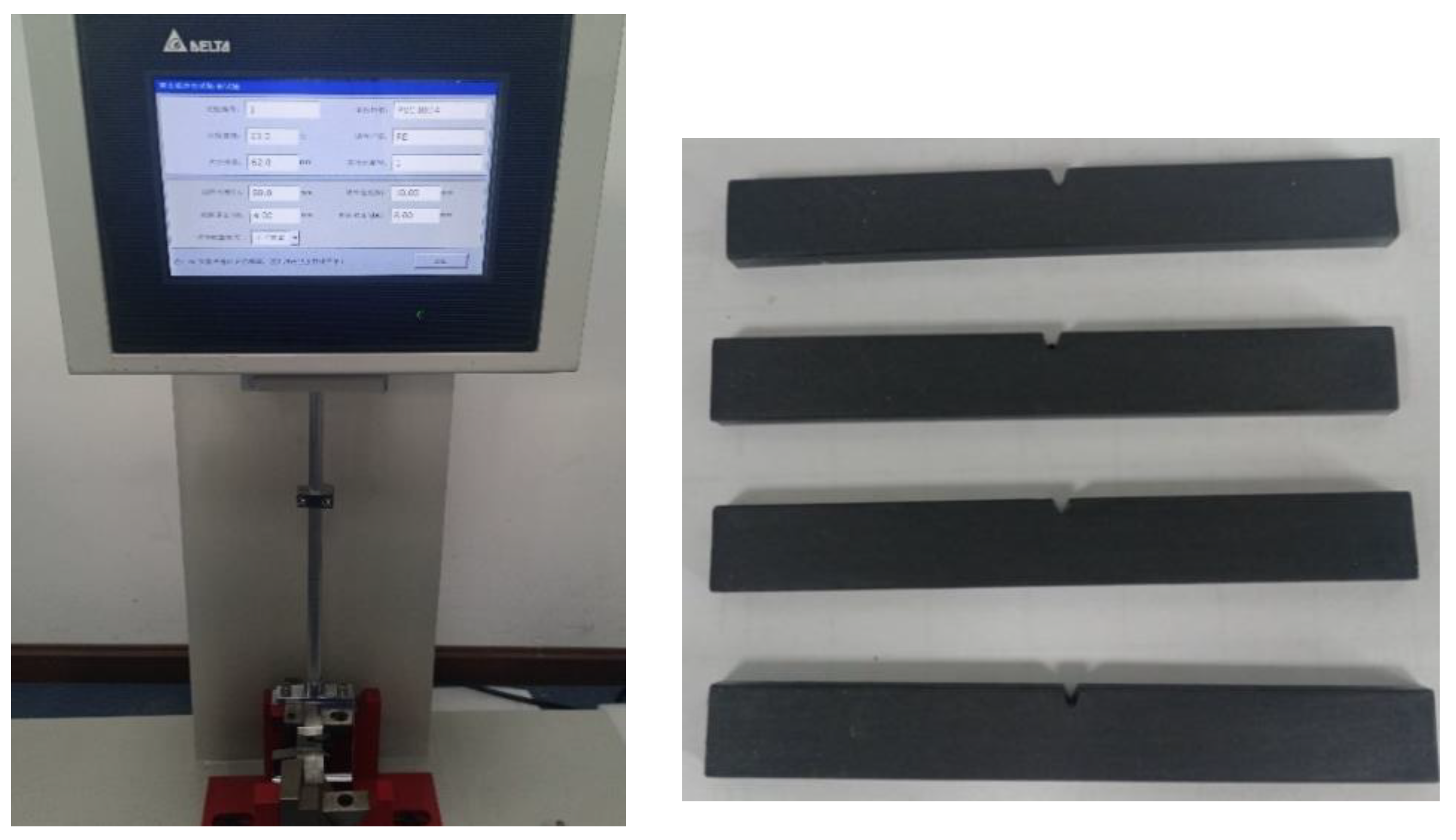

2.2.2. Impact strength and tensile test

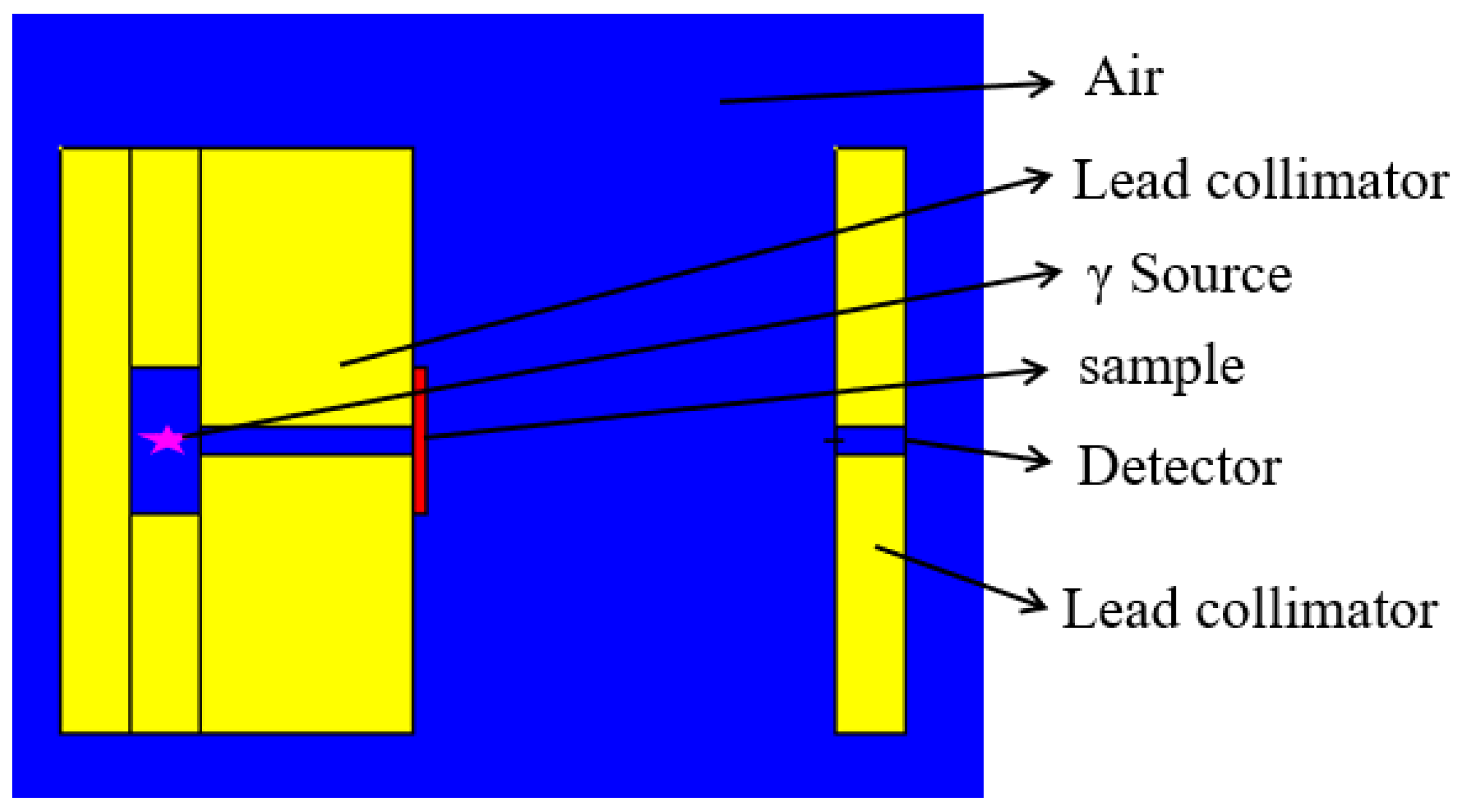

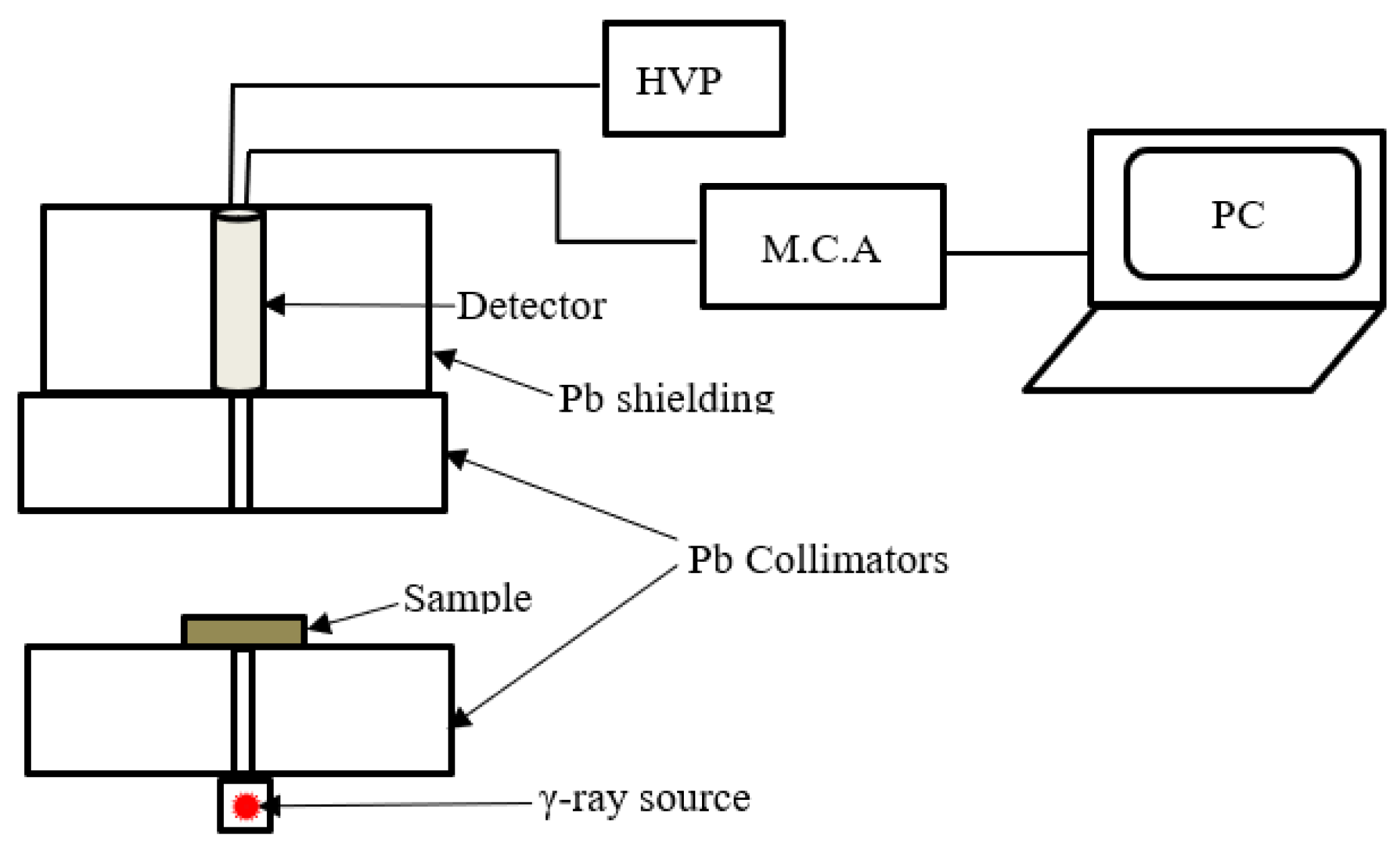

2.2.3. γ-ray shielding properties test

3. Results and Discussion

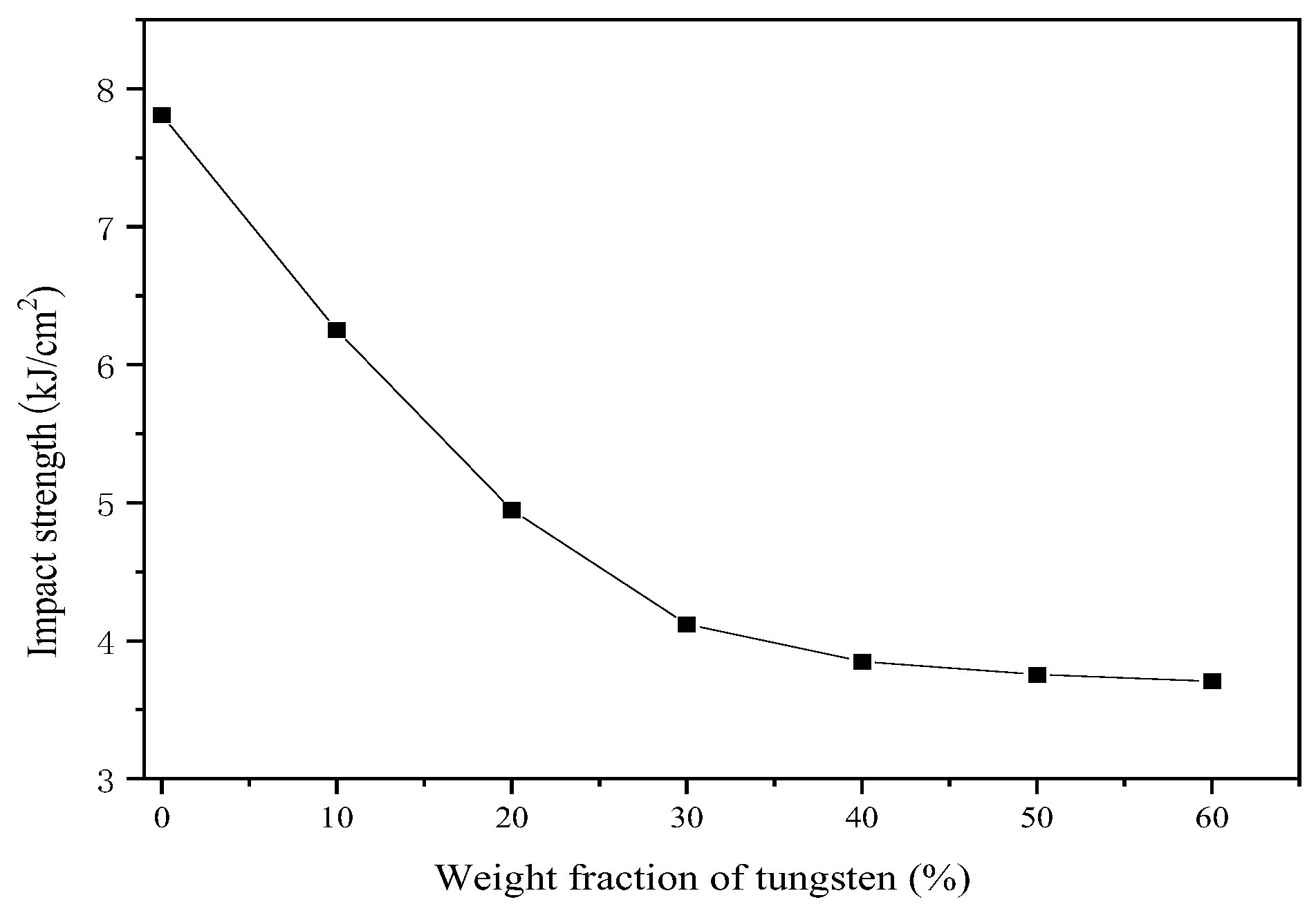

3.1. Impact strength

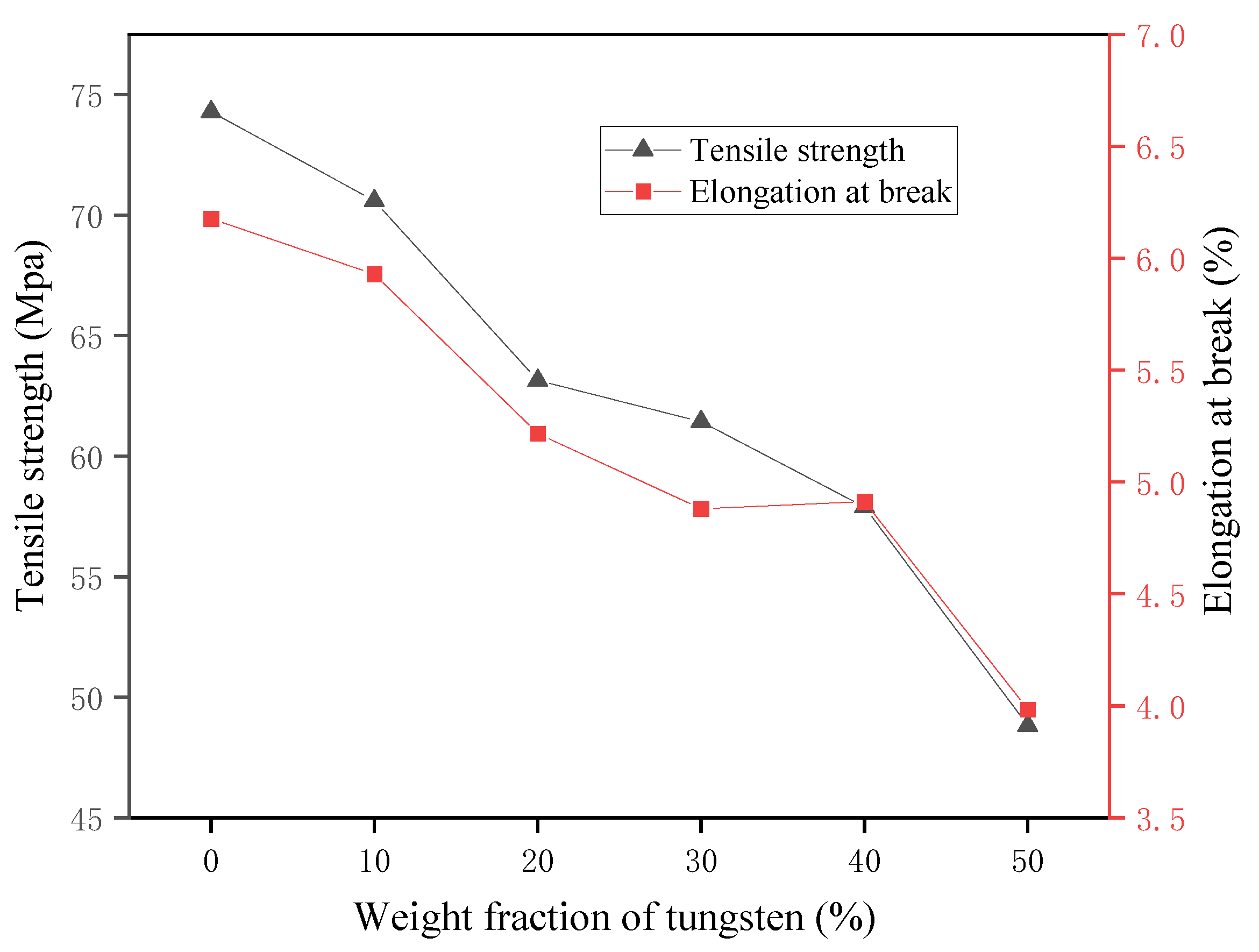

3.2. Tensile properties

3.3. γ-ray shielding properties

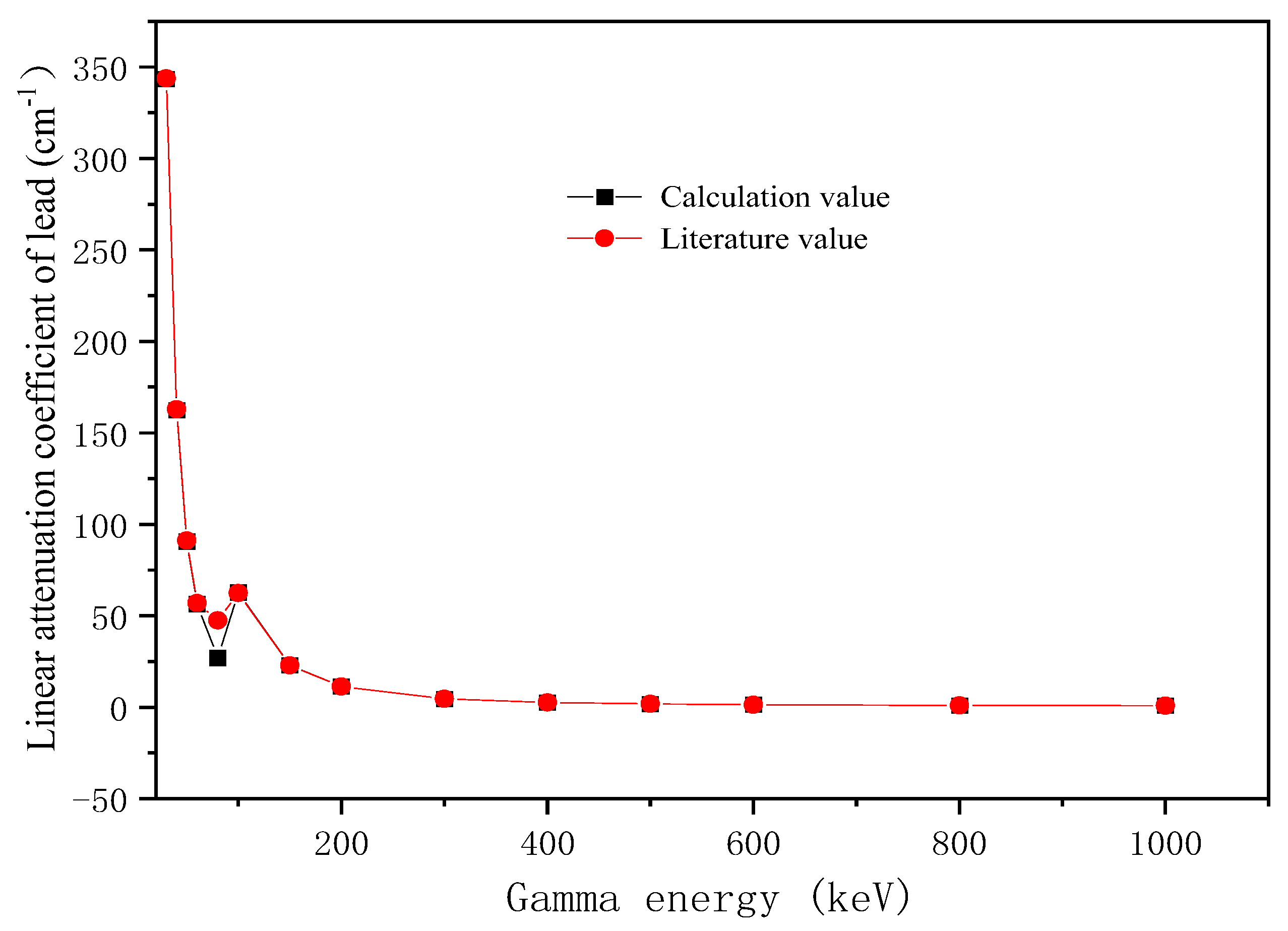

3.3.1. Verification of calculation

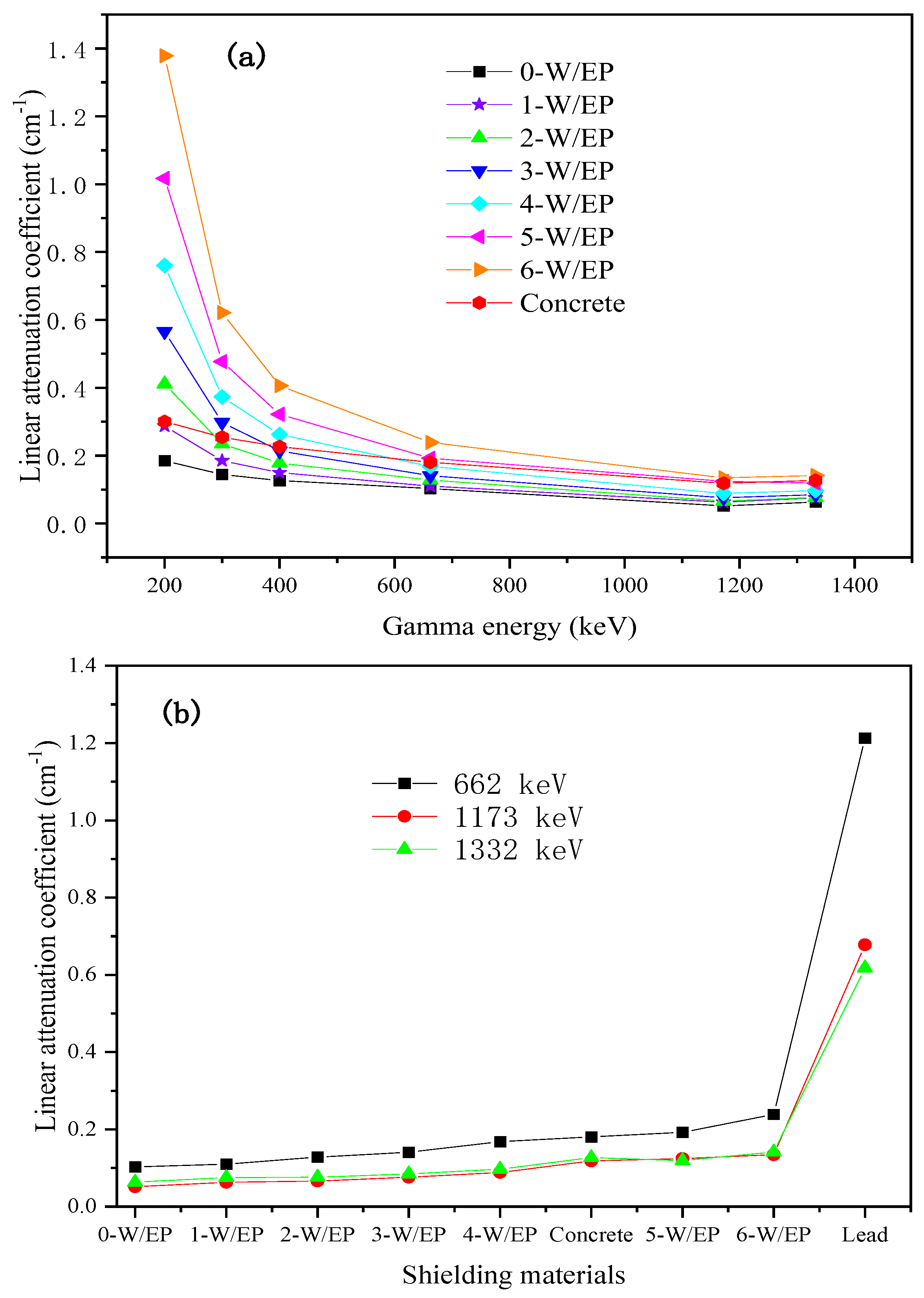

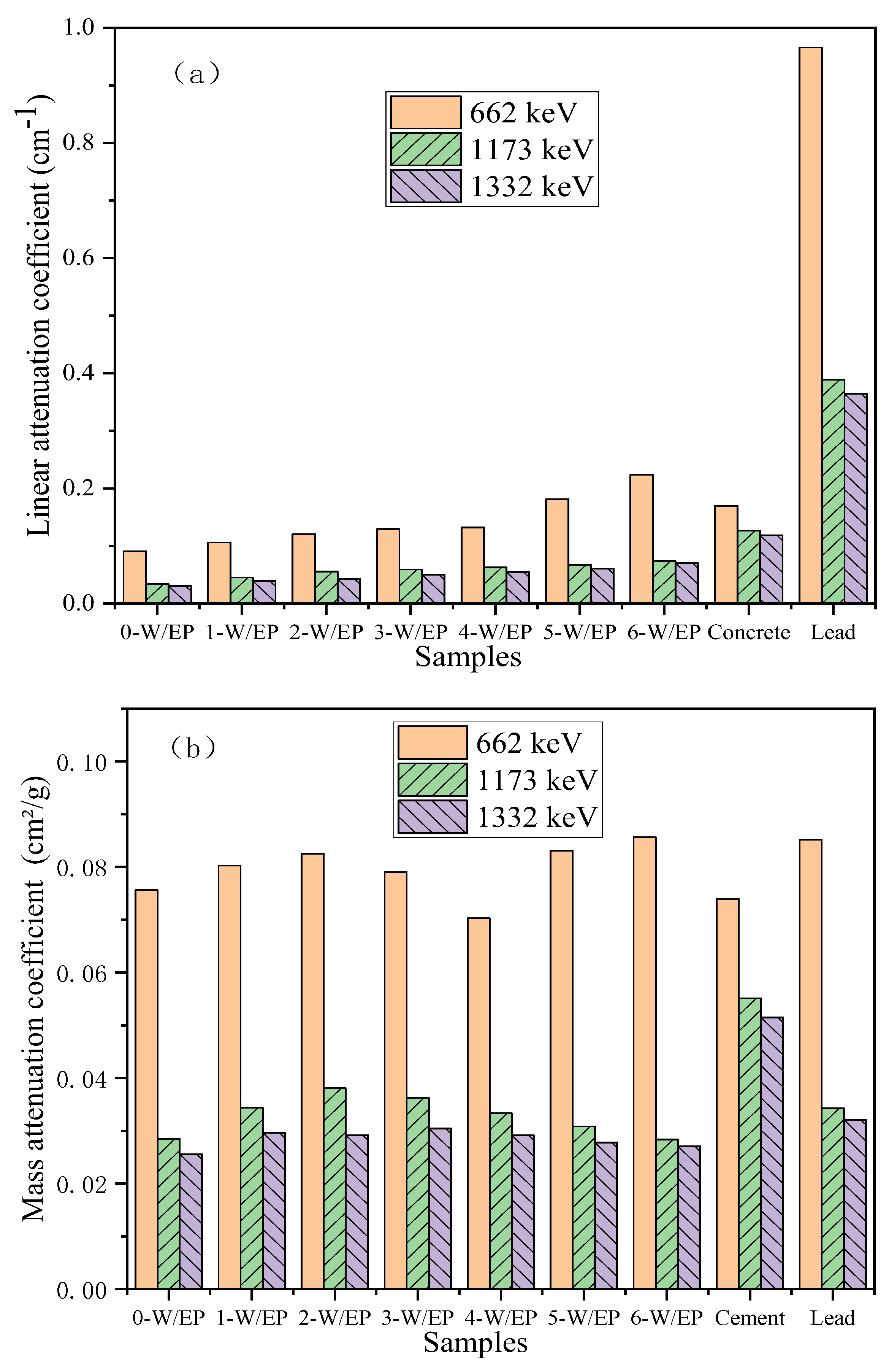

3.3.2. Linear and mass attenuation coefficient

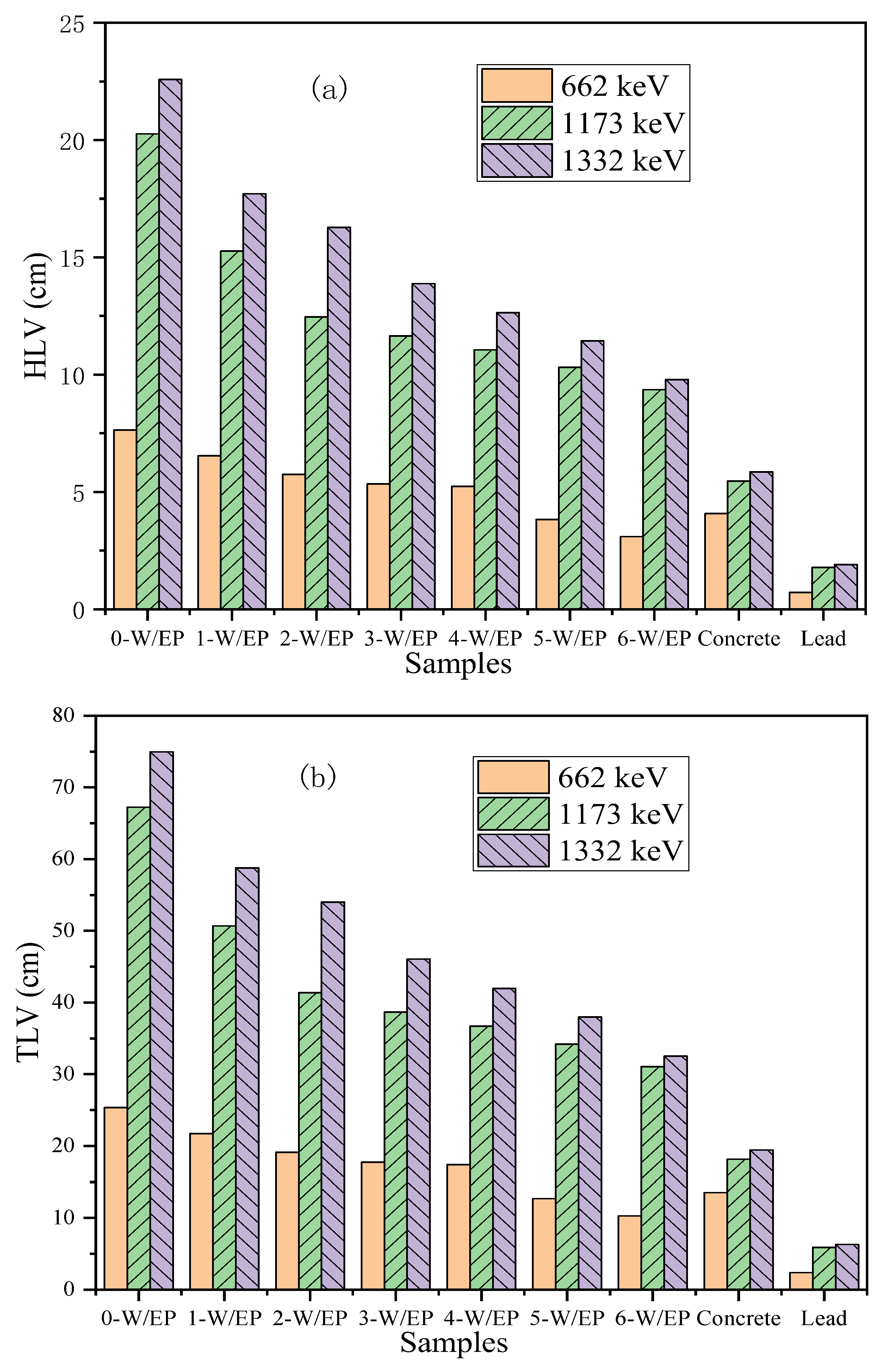

3.3.3. Evaluation of HVL and TVL

4. Conclusions

- The calculated results indicate that W/EP has comparable shielding capabilities to ordinary concrete at gamma-ray energies of 200 keV, 300 keV, and 400 keV, with tungsten weight fractions of 20%, 30%, and 50%, respectively.

- The experimental linear attenuation coefficient of W/EP composites is in agreement with the calculated value, but is 5-15% lower than the calculated result.

- The linear attenuation coefficient of W/EP composites decreases significantly with increasing γ-ray energy, suggesting that thicker shielding materials are necessary to meet the requirements for higher energy γ-ray shielding.

- The calculated and experimental results reveal that the shielding capability of 6-W/EP composite is slightly inferior to that of concrete for high energy γ-rays with energies of 1773 keV and 1332 keV. Moreover, the shielding capability of 5-W/EP composite is slightly lower than that of pure lead but superior to that of concrete in terms of shielding 662 keV γ-rays. These findings suggest that W/EP composites have more advantages in shielding low-energy γ-rays.

- The impact strength, tensile strength, and elongation at break of W/EP composites decrease as the tungsten content increases. This is due to a reduction in interfacial force between tungsten and epoxy resin, as well as an increase in tungsten powder agglomeration with higher tungsten content, which leads to a deterioration in mechanical properties. Therefore, it is suggested that excessive addition of tungsten powder should be avoided in practical applications. In summary, an increase in tungsten content results in a decrease of mechanical properties but an increase of gamma-ray shielding capability in W/EP composites, making them more suitable for shielding low energy gamma-rays. The 3-W/EP composite with a 30% tungsten content exhibits comparable shielding capacity to ordinary concrete for 662 keV γ-rays. Additionally, W/EP composites are environmentally friendly and non-toxic materials, indicating their high potential for various applications.

Conceptualization

References

- Angelo, J.A. Nuclear technology. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004, pp. 443–484.

- Shultis, J.K.; Faw, R.E. Radiantion Shielding technology. Health Phys. 2005, 88, 587–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirji, R.; Lobo, B. Radiation shielding materials: A brief review on methods, scope and significance. Proceedings of the National Conference on ‘Advances in VLSI and Microelectronics. 2017.

- More, C.V.; Alsayed, Z.; Badawi, M.S.; Thabet, A.A.; Pawar, P.P. Polymeric composite materials for radiation shielding: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2057–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharita, M.H.; Yousef, S.; Alnassar, M. Review on the addition of boron compounds to radiation shielding concrete. Prog. Nucl. Energ. 2011, 53, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, R.J.; Shivamurthy, B.; Kulkarni, S.D.; Kumar, M.S. Hybrid polymer composites for EMI shielding application- A review. Mater. Res. Express. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Alarifi, I.M. Advanced selection in polymer-composite materials for radiation shielding and their properties-A comprehensive review. J. Nucl. Radiat. Sci, 2022, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C. Tungsten-Based Hybrid Composite Shield for Medical Radioisotope Defense. Materials 2022, 15, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, M.; Qin, Q.; He, X.; Li, F.; Wang, X. Shielding Capability Research on Composite Base Materials in Hybrid Neutron-Gamma Mixed Radiation Fields. Materials 2023, 16, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ślosarczyk, A.; Klapiszewski, Ł.; Buchwald, T.; Krawczyk, P.; Kolanowski, Ł.; Lota, G. Carbon Fiber and Nickel Coated Carbon Fiber–Silica Aerogel Nanocomposite as Low-Frequency Microwave Absorbing Materials. Materials 2020, 13, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Geng, L.Y.; Qiu, S.Y.; Zou, H.W.; Liang, M.; Deng, D. Research progress of rare earth composite shielding materials. J. Rare. Earth. 2023, 41, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhai, Y.T.; Song, L.L.; Mao, X.D. Structure-thermal activity relationship in a novel polymer/MOF-based neutron-shielding material. Polym. Composite. 2020, 41, 1418–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyed, M.I.; Yasmin, S.; Almousa, N.; Elsafi, M. Shielding Properties of Epoxy Matrix Composites Reinforced with MgO Micro- and Nanoparticles. Materials 2022, 15, 6201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.W.; Lee, J.W.; Yu, S.; Baek, B.K.; Hong, J.P.; Seo, Y.; Kim, W.N.; Hong, S.M.; Koo, C.M. Polyethylene/boron-containing composites for radiation shielding. Thermochim. Acta. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hema, S.; Sambhudevan, S.; Mahitha, P.M.; Sneha, K.; Advaith, P.S.; Sultan, K.R.; Shankar, B. Effect of conducting fillers in natural rubber nanocomposites as effective EMI shielding materials. Mater. Today. [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Lu, L.; Xing, D.; Fang, H.; Liu, Q.; The, K.S. A carbon-fabric/polycarbonate sandwiched film with high tensile and EMI shielding comprehensive properties: An experimental study. Compos. Part B-Eng. 2018, 152, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, R.; Wang, K.; Wu, D.; Wang, C.; Zhang, M. Insight into the role of free volume in irradiation resistance to discoloration of lead-containing plexiglass. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fang, J.; Luan, W.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W. Preparation and characterization of tungsten/epoxy composites for γ-rays radiation shielding. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B. 2015, 356, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, F.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Fang, J.; Luan, W.L. Preparation and properties of tungsten epoxy resin γ-ray shielding composites. Thermo. Resin 2016, 31, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, B.; Shah, G.B.; Malik, A.H.; Rizwan, M. Gamma-ray shielding characteristics of flexible silicone tungsten composites. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes. 2020, 155, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boahen, J.K.; Mohamed, S.A.E.; Khalil, A.S.G.; Hassan, M.A. Finite Element Formulation and Simulation of Gamma Ray Attenuation of Single and Multilayer Materials Using Lead, Tungsten and EPDM. Materials Science Forum. Vol. 1069. Trans Tech Publications Ltd, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zalegowski, K.; Piotrowski, T.; Garbacz, A. Influence of Polymer Modification on the Microstructure of Shielding Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Zhuang, X.; Liu, J.; Han, J. Study on the properties of PPS composite modified with Tungsten powder, IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing, 2019, 592, 012025. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.S.; Yang, G.P.; Liu, Y.; Li, J. Effects of Tungsten content and Particle size on Properties of shielding Composites. Plast. Ind. 2015, 43, 72–75. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Yan, Q.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G.; He, L. Gamma radiation shielding properties of WO3/Bi2O3/waterborne polyurethane composites. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2022, 81, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejangah, M.; Ghojavand, M.; Poursalehi, R.; Gholipour, P.R. X-ray attenuation and mechanical properties of tungsten-silicone rubber nanocomposites. Mater. Res. Express. 2019, 6, 085045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, D.K.; Sayyed, M.I.; Botewad, S.N.; Obaid, S.S.; Khattari, Z.Y.; Gawai, U.P.; Pawar, P.P. Physical, structural, optical investigation and shielding features of tungsten bismuth tellurite based glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2019, 503, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavian, H.; Tavakoli, A.H. Study on gamma shielding polymer composites reinforced with different sizes and proportions of tungsten particles using MCNP code. Prog. Nucl. Energ. 2019, 115, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.Y.; Chen, H.H. Basis and Application of Ionizing Radiation Protection. Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China, 2016, pp. 50–51.

- Huo, L.; Liu, J.L.; Ma, Y.H. Radiation dose and Protection. Electronics Industry, Beijing, China, 2015, pp. 36–37.

| Sample labels | Tungsten fraction (wt%) | Nuclide components | Theoretical density | Experimental density | |||

| C | H | O | W | ||||

| 0-W/EP | 0 | 0.6875 | 0.0625 | 0.25 | 0 | 1.15 | 1.15 |

| 1-W/EP | 10 | 0.61875 | 0.05625 | 0.225 | 0.1 | 1.26 | 1.25 |

| 2-W/EP | 20 | 0.55 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.40 | 1.32 |

| 3-W/EP | 30 | 0.48125 | 0.04375 | 0.175 | 0.3 | 1.58 | 1.45 |

| 4-W/EP | 40 | 0.4125 | 0.0375 | 0.15 | 0.4 | 1.80 | 1.72 |

| 5-W/EP | 50 | 0.34375 | 0.03125 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 2.10 | 2.04 |

| 6-W/EP | 60 | 0.275 | 0.025 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 2.51 | 2.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).