1. Introduction

The designation of heritage conservation areas is a widely used planning tool for urban landscape management [

1]. Internationally, it is well-documented that the designation of heritage conservation areas continue to be resisted by communities due to unfounded assumptions of overly strict regulations and negative impacts on property values [

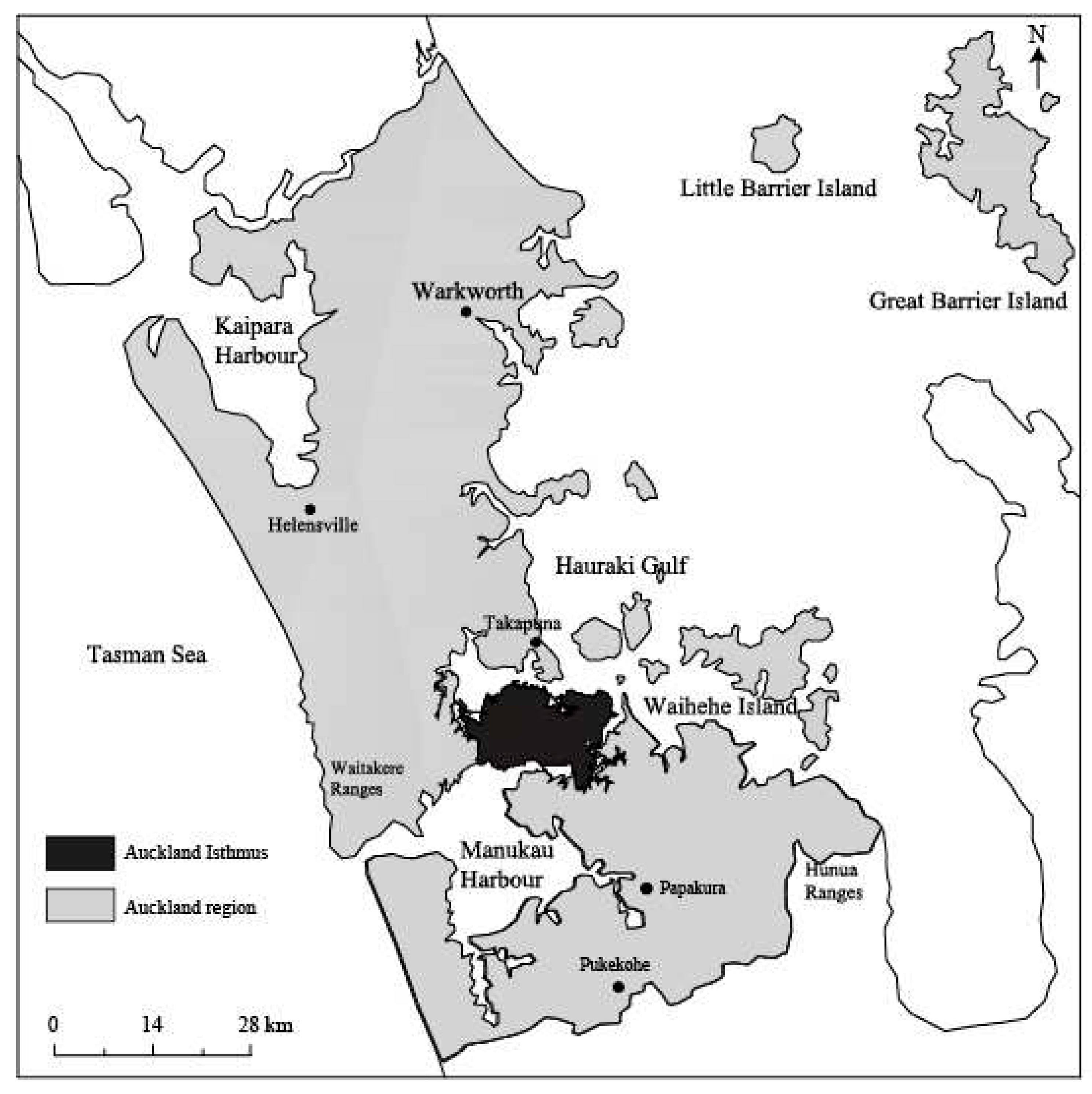

2]. Auckland is New Zealand’s most populous city, with approximately 1.72 million residents recorded in 2021. Auckland’s heritage is an important urban feature, despite being relatively young compared with other European cities. Planning regulations intended to protect and conserve heritage have shaped the configuration of Auckland [

3]. This includes Special Character Areas (SCAs), which are areas with notable or distinctive aesthetic, physical and visual qualities [

4]. These include qualities that relate to the history of an area, such as a predominance of buildings of a particular era or architectural style, or a distinctive pattern of lot sizes, street and road patterns.

Heritage conservation areas are a form of heritage protection used internationally to preserve areas of special architectural or historic interest and sustain the local character of an area [

5]. SCAs are similar to heritage conservation areas but are also unique as they are managed not for their historic value, but for their amenity, appearance and the aesthetic value of the streetscape, with controls on demolition, the design and appearance of new buildings, and additions and alterations to existing buildings [

3]. While the impact of heritage conservation area designation on property values and homeowners’ experiences is well-documented internationally, the impact of SCA designation on property values in Auckland has not been widely explored, nor the level of satisfaction of homeowners living in these areas. This research proposed to address these research gaps by seeking answers to the following research questions: How has the SCA designation affected property values? Are homeowners satisfied with living in SCAs?

These questions were addressed through a comprehensive investigation of two study SCAs in Auckland. The paper begins by explaining the use of Special Character Areas as a planning tool. Next, following a discussion of the research methodology, information on data collection and processing is presented. The main research findings and recommendations to improve the management of SCAs in Auckland are then summarised. The impact of SCAs on property values and homeowners’ experiences in the context of Auckland, New Zealand, generally align with research findings from other new world counties. Designated SCA properties have higher average property values than non-designated properties and homeowners are satisfied with living in a SCA. However, the absence of community engagement in the identification and management of SCAs and process strategies has undermined the implementation of SCAs. The development of management plans and design guidelines, which is based on the understanding of urban landscape character and its dynamic generative processes, is expected to help achieve valued spatial-temporal outcomes in SCAs in Auckland and beyond.

2. The Recognition of Heritage Conservation Areas and Special Character Areas as a Planning Tool in Auckland

Heritage conservation areas are fundamental to a civil society as they contribute to community identity and generate economic benefits in the form of urban vibrancy and cultural tourism. A general shift of attention from the individual historic monument to the scale of urban areas, precincts and districts emerged in the heritage discourse in the second half of the twentieth century. Area-based urban conservation became apparent in international declarations and charters between the 1960s and the 1970s and was more explicit in the Washington Charter of 1987: the ICOMOS Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas.

In addition to counterbalancing large-scale urban redevelopment, the designation of heritage conservation areas has been used to recognise buildings that might not meet the threshold for individual listing but have collective value as component parts of a community or a particular context. Heritage conservation areas are also referred to, apparently interchangeably, as heritage precincts [

6], conservation areas [

7] and heritage conservation districts [

8]. Through district plan measures such as scheduling and zoning, New Zealand’s first heritage conservation areas were recognised by local authorities in the 1970s. The New Zealand Historic Places Trust began its list of classified historic areas in 1981.

A heritage conservation area has a concentration of heritage resources with special character or historical association that distinguishes it from its surroundings. In terms of scale, such an area ranges from a small site with a group of buildings, to an urban precinct, to an entire city. The assessment of a historic heritage area is supported by insights into why a place has come to look the way it does and how the past is encapsulated in the landscape, highlighting its significant elements. Site (topography, vegetation, physical geographical features), ground plans (patterns of streets, lots and building block plans), building typology (viewed 3-dimensionally), land use and building materials are analysed in relation to the wider process of urban change. The assessment illuminates the character of an area, which is derived from a combination of different elements, including characteristics that are shared with other places or particular to that area. A historic heritage area is identified within a complex matrix that takes account of both professional judgment and community value.

The Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) is the primary environmental statute in New Zealand [

9]. The main purpose of the RMA is “to promote the sustainable management of natural and physical resources” (RMA, section 2). The RMA differentiates between the concepts – “special character” and “historic heritage”. Special character contributes to amenity value and under the RMA (section 7c), decision makers must give particular regard to the maintenance and enhancement of amenity values. With regard to historic heritage, it is among the matters of national importance listed under section 6 of the RMA, which requires decision makers to recognise and provide for the protection of historic heritage from inappropriate subdivision, use, and development (section 6f). Therefore, SCAs are managed for the amenity and appearance value of the streetscape, whereas historic heritage areas are managed to protect the values of the site including the authenticity and integrity of the historic fabric [

3].

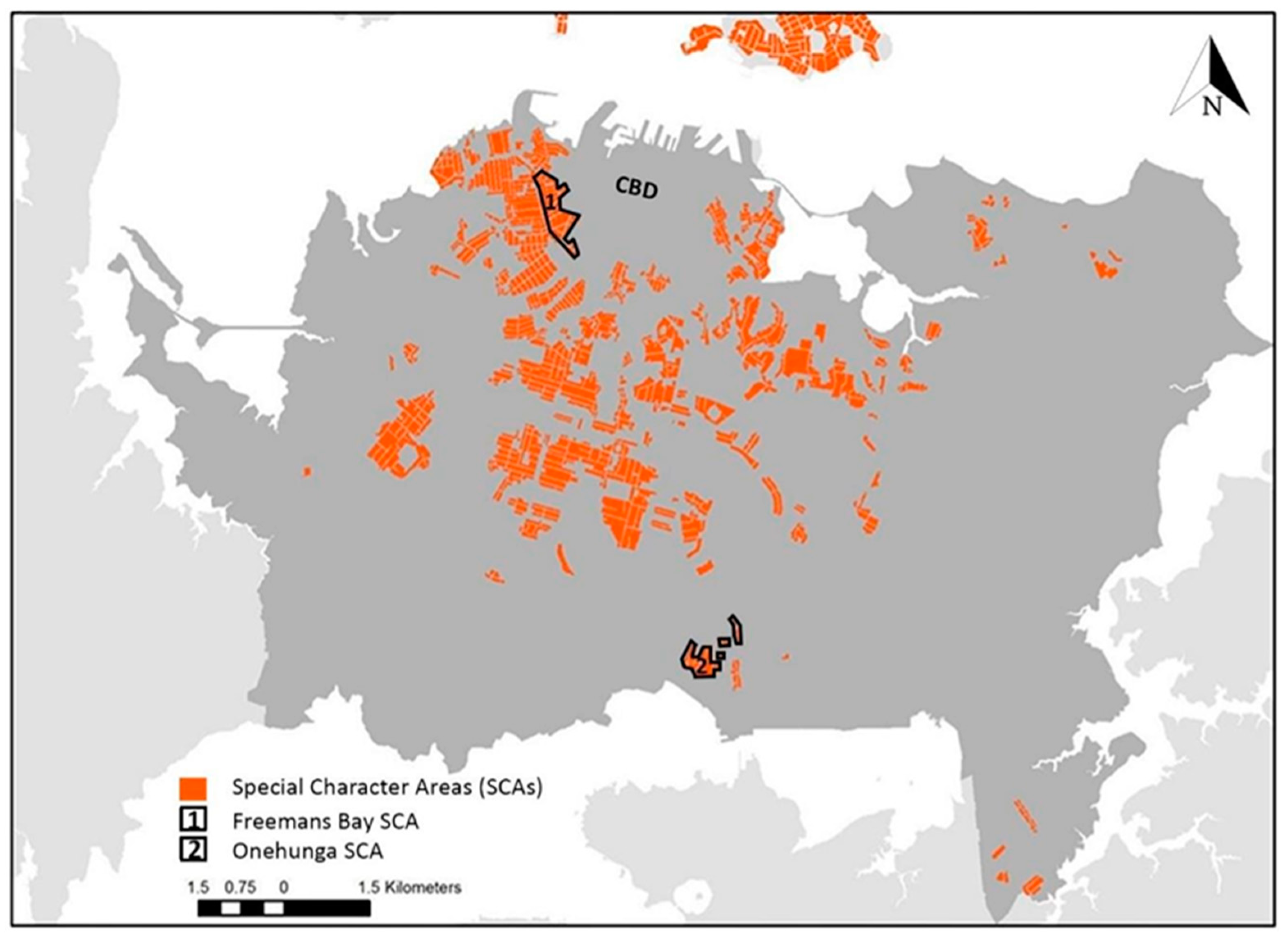

There are 50 Special Character Areas covering approximately 5.6% of land parcels in the Auckland region [

4]. SCAs are managed under the Special Character Areas Overlay – Residential and Business in the Auckland Unitary Plan (AUP). This overlay came into effect when the Proposed Auckland Unitary Plan (PAUP) became “operative in part” in November 2016. Previously, before the amalgamation of Auckland Council in 2010, SCAs were managed by the seven former city and district councils, namely Auckland City, Manukau, Waitakere, North Shore, Papakura, Rodney and Franklin.

The SCA overlay seeks to retain and manage the special character values of specific residential and business areas identified as having collective and cohesive value, importance, relevance and interest to communities within the locality and wider Auckland region. Planning provisions focus on external building works but not on the use of those buildings. The planning provisions are generally protective, but also enable appropriate development through the requirement for Resource Consent for some activities, such as demolition, or the construction of a new dwelling. The overlay seeks to retain and manage the character of traditional residential neighbourhoods by retaining intact groups of character buildings and allowing sympathetic and compatible new infill housing and additions. Overall, the aim of the overlay is not to replicate older styles and construction methods, but to reinforce the predominant streetscape character [

10]. Most dwellings located in SCAs are zoned for single house use and no further development is enabled under the AUP [

9].

3. Choice of Study Areas

Located in the upper North Island, greater Auckland extends northward through coastal suburbs, westward to the bush-covered Waitakere ranges and sprawls over rolling hills to the south and east (

Figure 1). The administrative area of Auckland mainly occupies an isthmus between the Manukau and Waitemata harbours. Most of the isthmus had been surveyed by the 1860s and was being utilised to some degree by various forms of economic activity at that time. By the 1960s, it was largely built up [

11]. As one of the fastest-growing cities in Australasia, Auckland has experienced rapid population growth in recent years. This rapid growth has created challenges to urban conservation planning.

Many parts of the central isthmus are covered by Special Character Area protection rules [

4]. Freemans Bay and Onehunga were selected as study areas in the central isthmus (

Figure 2) as they present different contexts, allowing for comparison. Freemans Bay sits just to the west of Auckland’s CBD. It is one of the oldest suburbs in Auckland, featuring a mix of residential developments. Land purchased for subdivision from the chiefs of Ngāti Whātua in 1842 was first developed along the shoreline [

13]. Freemans Bay evolved over the following few decades into a seaside village with a range of small marine industries and a growing number of workers’ cottages. The community still possesses many well-preserved old houses. By the 1920s Freemans Bay had reached its peak in terms of building density with a population of 10,500 [

13]. Freemans Bay became the first New Zealand suburb to be officially declared a ‘reclamation area’ under the provisions of the Housing Improvement Act 1945 [

14]. This enabled the local authority to completely replan and rebuild an area based on wide powers for land acquisition, demolition, subdivision, reconstruction and resale [

14]. Freemans Bay occupies an important place in New Zealand’s planning history as the first substantial attempt at urban renewal, albeit one that never fully eventuated.

Onehunga is a residential and light-industrial suburb next to the Port of Onehunga, the city’s small port on the Manukau Harbour. It is about 10 kilometres south of the city centre, close to the volcanic cone of Maungakiekie (One Tree Hill). The early development of Onehunga was largely due to the creation and growth of the colonial ‘fencible’ settlement. During the nineteenth century most shipping between New Zealand and Great Britain came to Onehunga, via South Africa and Australia [

15]. By the First World War, Onehunga was no longer an important commercial port, this was partly because of a general increase in the size of ships, which meant the Waitematā Harbour was favoured especially as it was wider and deeper. Although the area was a predominantly working-class suburb for much of the twentieth century, it has undergone some gentrification since the 1990s and many of the bungalows of the inter-war period along with the earlier villas have been restored [

15].

In Freemans Bay, the area designated as an SCA is larger than in Onehunga and residential properties are only designated in the Special Character Areas Overlay Residential and Business – Residential Isthmus A. In comparison, in Onehunga most of the SCA area is designated as Special Character Areas Overlay Residential and Business – Residential Early Road Links, with only some residential properties designated as Residential Isthmus A. This is important because in Residential Isthmus A, all sites are subject to the demolition, removal and relocation rules. However, in the SCA – Residential Early Road Links, not all sites are subject to these rules under Chapter D18 of the AUP. Freemans Bay was chosen as a study SCA because of its close proximity to the Auckland CBD (2km), whereas Onehunga is located in the outer suburbs, 10km from the CBD. Distance from the CBD was one variable assessed to determine whether it impacted property values and a homeowner’s satisfaction with living in a SCA.

Within the study SCAs, there is evidence of early development in small lot sizes, often narrow road widths and closely spaced housing. Late Victorian and Edwardian villas of one and two-storeys are evident and represent the early period of residential development (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Freemans Bay was traditionally a walking suburb because of its proximity to the city centre. In Onehunga, residential development was built along the main transport connections and designed to impress the passer-by, with cheaper housing relegated to less visible areas [

16].

4. Methodology

A property value analysis and an online questionnaire survey were employed to examine the two study areas. The property value analysis provided the basis for determining whether SCA designation exerts a statistically significant effect on property values [

4]. In this study, capital value was used as an indicator to understand whether SCA designation positively or negatively impacted property values in the study areas. Capital value is determined by Auckland Council through a mass appraisal. Auckland Council uses the latest data for homes sold in the area along with the existing data in their database regarding a property and then derive the capital value with these figures.

Before collecting property data, the study areas were separated into different sections. Once the data had been collected, it was analysed using Microsoft Excel. The address, capital value and land-use of 11,339 properties in both SCAs and their surrounding areas were collected. Non-residential properties were excluded from the data, leaving 9,854 properties. Vacant residential sites were also excluded from the data, leaving 9,754 residential properties. Residential properties within the Business SCA were excluded as well. Properties designated as SCA were then identified. In the Freemans Bay SCA, 690 properties were identified, while 324 properties were identified in the Onehunga SCA. Residential properties with capital values of more than $8 million were excluded as outliers. Lastly, the mean, median and standard deviation of capital values inside the SCAs and in the areas surrounding Freemans Bay and Onehunga were calculated. Mean, median and standard deviation statistics were used to draw inferences from this research.

An online questionnaire survey using the platform Google Forms was the method chosen to gather information on the perceived benefits and problems associated with SCAs and homeowners’ experiences and level of satisfaction. The online questionnaire enabled data to be collected efficiently and allowed participants to answer the questionnaire at a time convenient to them. The questionnaire was designed with a user-friendly layout and comprised only 10 questions, requiring just 3 to 5 minutes to complete. The recruitment method used was a mass mail-out process, in which homeowners were contacted directly by post to invite them to participate in the study. This occurred in September 2020 and each letter contained a hardcopy Participant Information Sheet and invitation to complete the anonymous online questionnaire on Google Forms by scanning a QR code or entering a link in a browser. Overall, 400 letters (200 in each study area) were placed in letter boxes in the SCAs of Freemans Bay and Onehunga. Houses were chosen at random within the SCAs without prior assumptions in order to avoid any form of bias.

5. The Impact of Special Character Areas on Property Values and Homeowners’ Experiences

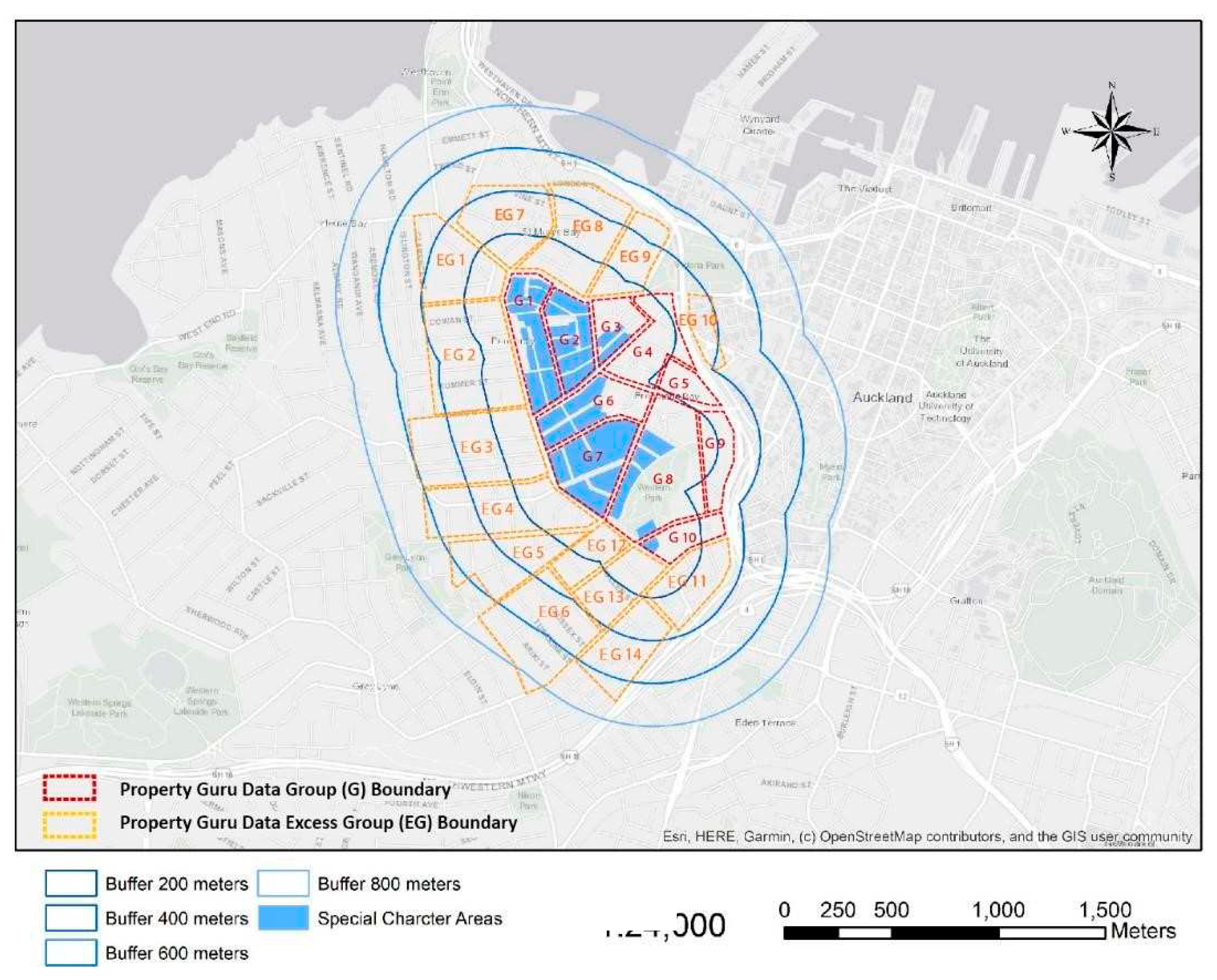

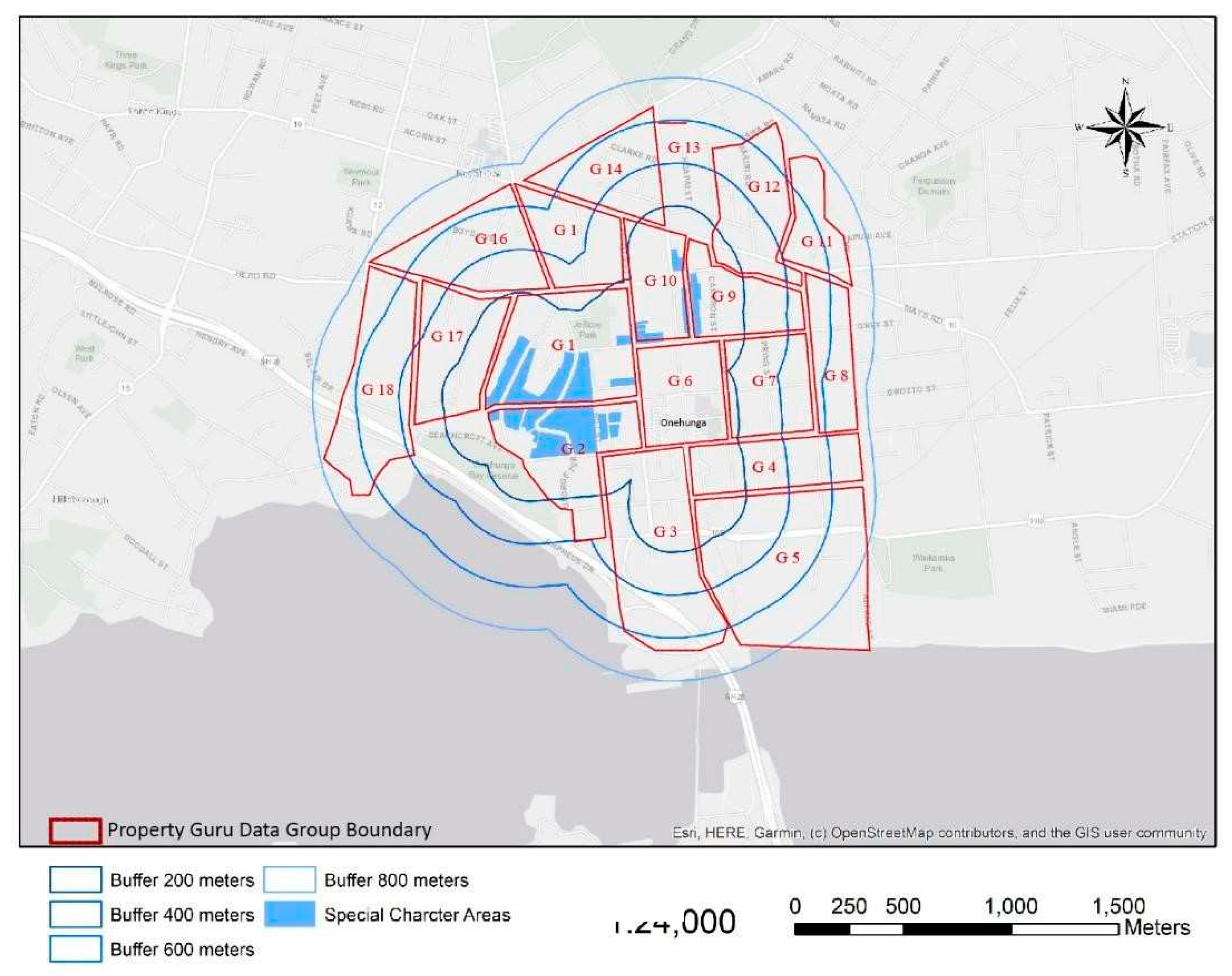

An examination of capital values (CV) was completed, as presented in

Table 1. The table shows the mean differences between capital values inside the SCAs and the surrounding areas. The highest average capital value was identified in designated SCA properties in Freemans Bay, at

$2,012,290. Non-designated SCA properties in Onehunga showed the lowest average capital value, at

$980,792. Surprisingly, the surrounding areas in Freemans Bay and Onehunga had a higher average capital value than the non-designated properties in closer proximity (see

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

Within Freemans Bay, the difference in average capital values between properties designated and not designated as SCA amounts to $1,005,533, or 50%. Moreover, the difference between average capital values for Freemans Bay properties designated as SCA and those in the surrounding areas is $563,751, or 72%. Within Onehunga, the difference in average capital values between properties designated and not designated as SCA amounts to $148,853, or 87%. The difference in average capital values for Onehunga properties designated as SCA and those in the surrounding areas is $120,095, or 89%. Designated SCA properties in Freemans Bay were found to have a higher average capital value than designated SCA properties in Onehunga. Specifically, designated SCA properties in Freemans Bay had an average capital value of $2,012,290, whereas in Onehunga the average CV was $1,129,645.

Non-designated SCA properties in Freemans Bay were also found to have a higher average capital value than non-designated properties in Onehunga. Non-designated SCA properties in Freemans Bay had an average CV of $1,006,757, whereas non-designated properties in Onehunga have an average CV of $980,792. Properties in the surrounding areas of Freemans Bay have a higher average capital value than the surrounding areas of Onehunga, at $1,448,539 and $1,129,645, respectively.

These findings suggest a positive impact of Special Character Area designation on property values in the study areas. There is a positive internal benefit from SCA designation, resulting in premium capital values in designated properties compared to similar non-designated residential properties. In Freemans Bay there is a premium of 50% and in Onehunga, the premium is 87%. The findings also show a positive external benefit from designation, resulting in a capital value premium for properties in neighbourhoods surrounding both SCAs in the study. In Freemans Bay there is a capital value premium of 87% and in Onehunga the capital value premium is 89%. The positive impact on property values found in this study suggests that the positive externalities of the designation outweigh the restrictiveness of the preservation rules. Furthermore, owners in surrounding areas can benefit from higher property values without incurring the regulatory costs associated with being designated.

The questionnaire survey was completed by 99 people (58 in Onehunga and 41 in Freemans Bay), with an overall response rate of around 25%. Two survey questions were aimed at understanding satisfaction among homeowners in SCAs. The responses revealed that homeowners in both study areas were overwhelmingly satisfied with living and owning a property within a SCA. Of the 99 homeowners surveyed, 50 (50.5%) stated they were very satisfied, with an additional 28 homeowners (28.3%) stating they were satisfied. Therefore, a total of 78 people (78.8%) were found to be satisfied with living in a SCA. In contrast, only 12.1% of homeowners were dissatisfied – 3 dissatisfied and 9 very dissatisfied.

Sense of community and appreciating the attractive character and history of the area were identified as significant factors in achieving a feeling of satisfaction. Location and access to the CBD and amenities were also noted by respondents as factors contributing to a high level of satisfaction with living in the area. Questionnaire responses also revealed why some homeowners were generally dissatisfied with living in an SCA. Several respondents were dissatisfied because they believed the SCA rules were too restrictive, had issues with parking and were not able to do what they wanted with their property. While some respondents thought there was not enough protection from the SCA overlay, they noted that the SCA overlay was not applied consistently and shared concerns over new buildings being constructed in the SCA that are out of place and do not fit with the established character of the area.

Benefits identified by questionnaire included feeling a sense of community and having certainty around the look and feel of their neighbourhood in the future. The requirement for a Resource Consent in SCAs was identified by respondents as both a benefit and an issue with living in the area. However, attitudes towards the need for Resource Consent in the study areas were generally positive.

Two survey questions aimed to understand perceived value. Specifically, one of the questions was: "Could you rate the following statement: The constraints placed on property owners in Special Character Areas regarding the need for a Resource Consent is a significant negative attribute to living in the area?" The results show that the majority of respondents thought the requirement for Resource Consent was not a significant negative attribute of living in the area. In both study areas, over a quarter (29.3%) of respondents disagreed with this statement, with an additional 26.3% of respondents strongly disagreeing that this requirement was a significantly negative attribute to living in the area. In contrast, only 14.1% of respondents strongly agreed and 12.1% agreed this requirement was a significantly negative attribute.

The other question was: “Could you rate the following statement: The constraints placed on property owners in Special Character Areas regarding the need for a Resource Consent is important in maintaining the attractiveness of the area?” The results show that the majority of respondents thought the requirement for Resource Consent was important in maintaining the attractiveness of the area. In both study areas, over 44.4% of respondents strongly agreed with this statement, with an additional 24.2% agreeing that the requirement for a Resource Consent was important in maintaining the attractiveness of the area. In contrast, only 4% strongly disagreed and 14.1% disagreed that the requirement was important to maintaining the attractiveness of the area. It should be noted that many respondents had never applied for a Resource Consent for their property. Specifically, across both study areas, 63.6% of respondents had never applied for a Resource Consent for their property.

Among respondents who had applied for a Resource Consent for their property, 52.7% (9 negative and 10 very negative) found it to be a negative experience, 30.5% of respondents found it to be a positive experience (9 positive and 2 very positive), while 16.8% of respondents had neither a positive nor negative experience. A key theme in both study areas was that the Resource Consent process is very challenging, too restrictive and very costly in terms of both time and money. Several respondents also identified issues with making minor changes to maintain their property and in some cases thought the Resource Consent process was too intrusive and restrictive because Council can decide where windows should be located.

6. Planning and Managing the Changing Special Character Areas

The following recommendations are intended to improve the identification and management of SCAs in Auckland. They are based on analysis of questionnaire respondents’ experiences and perceptions of what it is like to live in an SCA. The recommendations are important considering the inherent tension evident between maintaining character and increasing density, the development pressures faced by SCAs, and the need to stay relevant in response to resident’s ever-changing lifestyles.

The first recommendation is that Auckland Council increase public awareness of SCAs across Auckland because some questionnaire respondents were not aware they lived in an SCA. Auckland Council should also increase community involvement and work with resident societies and residents located in SCAs across Auckland. This would help ensure SCAs are valued by communities and not resisted, and that the quality of life for residents of SCAs is not detrimentally affected. Auckland Council therefore needs to explore funding and resource options for community building exercises. The use of “pop up” events could assist in defining the objectives of SCAs and explaining the rules to residents because one questionnaire respondent identified that the rules can be difficult to understand. These events would also provide an opportunity for residents to discuss the issues they have faced with the Resource Consent process so Auckland Council can identify ways to improve it.

Secondly, it is recommended that Auckland Council involve the community more in the identification of SCAs in Auckland. SACs are expected to be a product of practical reasoning and sensitive to context and consequences. Some respondents thought that the SCA designation is applied inconsistently, with the process of evaluating streetscapes perceived to be quite a subjective process carried out exclusively by Council planners. Each SCA tends to be historically influenced in two ways: first, through the environment provided by existing forms, especially their layout; and secondly, by the way in which forms, most obviously buildings, though embodying the innovations of their period of construction, also embody characteristics ‘inherited’ from previous generations of forms. To understand this creation process of a SCA, it is necessary to appreciate not only the physical sequences of which the physical form is a product, but also the decision-making processes, planned and spontaneous, that it represents. Anyone should be able to request that an area be designated and Auckland Council should formulate criteria that can be used to assess areas nominated for potential designation. Auckland Council could undertake initial investigations to assess whether areas are worthy of further investigation. Nominations could then be shortlisted and processed together through a plan change. The delineation of the boundaries of SCAs needs to take into account both professional judgment and community values.

Thirdly, Auckland Council should consider developing design guidelines to ensure that new development within SCAs is sympathetic. Questionnaire respondents identified that currently new development does not reflect the character of the areas and is out of place. Traditionally, urban conservation in New Zealand is reactive and ineffective in guiding positive management of change to historic urban areas [

18]. There is a need to maintain and adapt houses within SCAs so they remain relevant for communities, but this should be done sympathetically and guidelines are needed. Auckland Council should prepare management plans for all SCAs. The historic urban environment can be seen as an accumulation of past experimental results and the refinement of practical solutions. Driven by individuals and agencies, there will be continuing modifications to the SCAs. Based on monitoring of any changes and agreement that a change is sufficiently beneficial, the demarcation of SCA areas and development control measures can be revised.

Finally, it is recommended that Auckland Council investigates the opportunity to achieve more integration between the Building Consent and Resource Consent processes. As one questionnaire respondent identified, currently a homeowner may obtain a Building Consent and Code Compliance Certificate (CCC), but then changes are often required in the Resource Consent process. This means applicants often need to redo or make significant changes to their plans, which costs time and money.

7. Conclusion

There has been a growing body of research on heritage conservation areas and property values [

19,

20]. While some research shows mixed, inconclusive, and even negative effects, many studies reveal a positive relationship between heritage area designation and increased property values [

21]. Auckland is a city obsessed with the property market. The economics of heritage buildings and areas have been of both professional and public interests [

22].

Like many towns and cities elsewhere, intensification pressures have created challenges to conservation planning in Auckland [

23,

24,

25]. This research investigated the impact of Special Character Area designation on property values and homeowners’ experiences in Auckland, using Freemans Bay and Onehunga as the study areas. Special Character Areas are areas with notable or distinctive aesthetic, physical and visual qualities, such as a predominance of buildings of a particular era or architectural style. Unlike countries with a long history, New Zealand’s heritage is relatively young and SCAs are protected for their amenity rather than their historic value.

Two methodologies were implemented to provide both quantitative and qualitative analyses. A property value study was used to analyse the impact of SCA designation on property values inside the study areas and their surrounding areas using capital values as an indicator. Additionally, an online questionnaire survey was adopted as a method to gather information on the perceived benefits and issues associated with SCAs and homeowners’ experiences and level of satisfaction.

It is evident that homeowners are overwhelmingly satisfied with living in an SCA and there is a positive impact on property values from SCA designation. Perceived benefits were identified as a sense of community and having certainty around the look and feel of their neighbourhood into the future. The requirement for a Resource Consent was perceived to be both a benefit and an issue by respondents. The requirement was seen as important in maintaining the attractiveness of the area, but many respondents viewed it as a very slow and costly process. They also found it difficult to make minor changes to maintain their properties. Special Character Areas are a form of living heritage that accommodates daily life. Development controls therefore need to ensure the continuity of the evolutionary process of the historic urban landscape and social-cultural development.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has in recent times formulated and since promoted the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach for integrating heritage management and urban development, publishing the Vienna Memorandum on World Heritage and Contemporary Architecture: Managing the Historic Urban Landscape (2005), and the General Conference Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (2011) [

26]. The integrated management of historic cities seeks to secure their evolutionary development, taking into account issues of ecological sustainability as well as geo-cultural distinctiveness and identity. It is as much people-driven as artefact-driven, focusing on the inhabitants and others who conduct their daily lives within historic cities, without which they serve a limited range of activities and lack the essential ingredients of spirit of place.

The SCAs define a large part of Auckland’s urban character and connect people to a place [

27]. The significance of the SCAs is justified by their economic and community benefits. Maintaining and enhancing a multiplicity of SCA values therefore merit a careful planning response. The usefulness of the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach resides in the notion that it incorporates a capacity for change. It has the potential to form the basis for development coordination and control that ensure future urban changes to fit coherently into existing urban structures. The involvement of planners, community groups and property owners in the management process of SCAs facilitates successful decision-making. The planning provisions, management plans and guidelines should reflect a consensus on what to protect, assessing vulnerability to change, and prioritising actions.

References

- Shipley, R. Heritage designation and property values: Is there an effect? Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2000, 6, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, R.; Jonas, K.; Kovacs, J.F. Heritage conservation districts work: Evidence from the Province of Ontario, Canada. Urban Aff. Rev. 2011, 47, 611–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bade, D.; Castillo, J.G.; Fernández, M.A.; Aguilar-Bohórquez, J. The price premium of heritage in the housing market: Evidence from Auckland, New Zealand. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.A.; Martin, S.L. What’s so special about character. Urban Studies 2020, 57, 3236–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Historic England. Understanding Place: Historic Area Assessments; Historic England: London, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Heritage Council. Guidelines for the Assessment of Places for the National Heritage List, Canberra. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Australian Heritage Council, 2009.

- Bristol City Council. Shirehampton Conservation Area Character Appraisal. Bristol City Council: Bristol, 2023.

- Ontario Ministry of Culture. Heritage Conservation Districts: A Guide to District Designation under the Ontario Heritage Act: Ontario Heritage Tool Kit. Ontario Ministry of Culture: Toronto, 2006.

- Ahlfeldt, G.M.; Holman, N.; Wendland, N. An Assessment of the Effects of Conservation Areas on Value. 2012. Available online: https://historicengland.org.uk/content/docs/research/assessment-ca-valuepdf/ (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Warnock, C.; Baker-Galloway, M. Focus on Resource Management Law. LexisNexis NZ Limited: Wellington, 2014.

- Bloomfield, G.T. The growth of Auckland 1840-1966. In Auckland in Ferment, Whitelaw, J. S. Ed.; A special publication of New Zealand Geographical Society, Miscellaneous Series No. 6. New Zealand Geographical Society: Auckland, 1967; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Auckland Council. GeoMaps Mapping Service. Available online: https://www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/geospatial/geomaps/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Terrini, V. Freemans Bay - notes on urban renewal. Town Planning Quarterly 1972, 44, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, R. Urban renewal: a case history of Freemans Bay, Auckland, Part 1. Town Planning Quarterly 1972, 28, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, F.E. Manukau harbour: European settlement. In An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand; McLintock, A. H. Ed.; 1966.

- Auckland Council. The Auckland Unitary Plan Operative in Part. 2020. Available online: https://unitaryplan.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/pages/plan/Book.aspx?exhibit=AucklandUnitaryPlan_Print (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- CoreLogic. Residential Real Estate. 2019. Available online: https://www.corelogic.co.nz/ (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- McEwan, A. Heritage issues. In Planning practice in New Zealand, 2nd ed.; Miller, C.; Beattie, L. Eds.; LexisNexis NZ Limited: Wellington; 2022, pp. 249–259.

- Leichenko, R.M.; Coulson, N.E.; Listokin, D. Historic preservation and residential property values: An analysis of Texas cities. Urban Studies 2001, 38, 1973–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, P.V.; Millerick, C.A. The impact of historic district designation on property values: An empirical study. Economic Development Quarterly 1991, 5, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, C.A. House prices in a heritage area: The case of St. John’s, Newfoundland. Canadian Journal of Urban Research 2006, 15, 175–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs, J.F.; Galvin, K.J.; Shipley, R. Assessing the success of heritage conservation districts: Insights from Ontario, Canada. Cities 2015, 45, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auckland Council. Auckland’s Heritage Counts 2018: Annual Summary. Auckland Council: Auckland, 2018.

- Been, V.; Ellen, I.G.; Gedal, M.; Glaeser, E.; McCabe, B.J. Preserving history or restricting development? The heterogeneous effects of historic districts on local housing markets in New York city. Journal of Urban Economics 2016, 92, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzelman, M.D.; Altieri, J.A. Historic preservation: Preserving value. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 2013, 46, 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gu, K. Pingyao: The historic urban landscape and planning for heritage-led urban changes. Cities 2020, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, I.; Clark. J. Character and Identity: Townscape and Heritage Appraisals in Housing Market Renewal Areas. 2008. English Heritage and Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment. Available online: http://www.cabe.org.uk/publications/character-and-identity (accessed on 25 October 2022).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).