1. Introduction

The term "lean" originated from the Toyota production system and was first introduced by Krafcik (1988). When Womack and his colleagues wrote the book "The Machine that Changed the World" in 1990, it catalyzed the lean revolution. According to Mize et al. (2000), lean is not just a set of rules commonly seen in factory workshops, but a fundamental change in how people in the organization think and evaluate, thereby changing their behavior. Shah and Ward (2003) defined lean as a method to provide the highest value to customers by eliminating waste through process design and human factors.

Lean manufacturing is an early form of lean, describing production systems developed by the founders of Toyota in the late 1800s. Lean manufacturing aims to eliminate waste in all areas of production, including customer relations, product design, supplier networks, and plant management. Its goal is to combine less human effort, less inventory, less time to develop products, and less space to meet high customer demand while producing top-quality products in the most economical and efficient manner possible (Mize et al., 2000). Today, lean is a global trend applied to all industries and fields. Lean is no longer confined to the production environment but has expanded to include management and accounting environments.

Lean Accounting: The emergence of lean, primarily lean production, has created a need for lean accounting. As a provider of decision-making information, accounting is crucial to the success of the lean transformation process. However, when businesses shift to lean production, traditional accounting - based on standard cost, variance analysis, and shared cost allocation - is no longer suitable, and can even hinder lean production (Ramasamy, 2005; Arbulo-Lopez and Fortuny-Santos, 2010; Rao and Bargerstock, 2011; Maskell and Kennedy, 2007; Ofileanu and Topor, 2014) because traditional accounting only fits traditional mass production and not lean production.

Indeed, when businesses implement lean, their needs change. They require information about the financial impact of lean improvements, a better way to understand product costs, new ways to measure effectiveness, elimination of waste from accounting processes and systems, and better decision-making focused on customer value (Maskell et al., 2011). Thus, when businesses shift from mass production to lean production, the accounting system needs to change. Production cannot be sustained without significant changes to the accounting system. A suitable replacement for traditional accounting is lean accounting.

According to Maskell et al. (2011), lean accounting has the following characteristics: lean accounting focuses on managing the business around value streams. All cost and financial decisions are made at the value stream level; the lean accounting method is designed to promote continuous, relentless improvement of the value stream; lean accounting eliminates most waste from the control system by integrating control into operational processes. Eliminating the need for wasteful transactions, reports, and meetings leads to the use of simple, understandable reporting and cost methods; and lean accounting applies the principles of lean to accounting processes themselves.

Lean accounting has two main objectives: 1) Eliminate waste in production and accounting, while freeing up space and simplifying the process as much as possible so that everyone in the business can understand it, not just the accountants. 2) fundamentally change the accounting environment to provide relevant information to both customers and employees to support decision-making, allowing all employees to influence positive changes in the business.

Lean accounting aims to create conditions for the necessary changes in the organization to implement lean thinking (Ofileanu and Topor, 2014) and provide a stage for the accounting team to transition from a traditional system to a new high-value advisory role in different areas of the company (Cunningham et al., 2003). Lean accounting does not require traditional management accounting methods such as standard costing, variance reporting, complex transaction control systems, and untimely and confusing financial reports, but rather applies a value-based approach (Manjunath and Bargerstock, 2011). The tools of lean accounting are not entirely new and include value stream; Kaizen, PDCA, box score, value stream costing, target costing, financial reporting in simple language, visual management, 5S; sales, operations, and financial planning, etc. (Brosnahan, 2008; Maskell and Baggaley, 2006; Maskell et al., 2011).

Since 1996, the Vietnamese government has shown special interest in improving productivity and product quality. The national program "Improving productivity and product quality of Vietnam's goods by 2020" and the subsequent "National program to support businesses in improving productivity and product quality of goods in the period 2021-2030" are major turning points in promoting the application of various improvement systems, models, and tools to enhance productivity and quality nationwide. These programs have attracted the participation of thousands of businesses from various industries, with various scales, and have achieved significant achievements. Businesses have become familiar with some management systems and improvement tools, including lean management.

The textile and garment industry is one of the most important economic sectors, with export turnover ranking fourth among economic sectors (Ministry of Industry and Trade, 2022) and contributing 5-7% to Vietnam's GDP (VCBS, 2021). Vietnam is also among the top five garment exporters in the world. However, with the characteristics of highly fashionable products, it is necessary to regularly change designs, designs, colors and materials and in the context of rapidly increasing production costs, inflationary pressure, constantly rising living costs, the advantage of cheap labor is decreasing, labor productivity is low. More than ever, Vietnamese garment enterprises are forced to improve management, search and apply technology to increase labor productivity, maintain good competitiveness to ensure stable and sustainable development. With the characteristics of operation is mainly processing according to orders, products are produced according to customer requirements, diverse products, the number of products of each small order, orders change constantly, Vietnamese garment enterprises are considered one of the types of businesses that are very suitable for lean production. Therefore, since 2006, lean has been applied to some garment enterprises, first of all in production activities. Some enterprises have successfully applied lean production, such as: Nha Be Garment Corporation after applying lean working time has been significantly reduced, workers do not have to work overtime, average income increases by 10%, wages of workers between lines are more uniform, the backlog in working positions is less, so industrial hygiene is better and it takes less time to clean. Or Garment Corporation 10 after applying lean, labor productivity increased by 52%, defect rate decreased by 8%, working time decreased by 1 hour/day, income increased by 10%, production costs decreased from 5-10%/year (Le, 2015). Thus, the research of lean accounting in textile firms in Vietnam is necessary.

This research is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the studies of lean accounting and hypothesis development.

Section 3 describes the data sample collection and methodology employed in the conduct of the research.

Section 4 sets out a discussion of key results, while

Section 5 shows some key conclusions and implications of the study practice and recommendations.

2. The Literature Review

Maskell was the first to mention the term lean accounting, stating that “lean accounting aims to provide useful information to those who are making and maintaining lean production” (Maskell, 2000). In 2005, Maskell stated that it was the generic term used for changes required in a company's accounting, control, measurement, and management processes to support lean manufacturing and lean thinking. It supports a lean culture by fostering investment in people, providing appropriate and actionable information, and empowering continuous improvement at every level of the organization (Arora and Soral, 2017). Brosnahan (2008) argues that lean accounting is a new accounting method stemming from the growing interest of organizations in embracing the culture of lean thinking. It is applied in organizations implementing lean thinking (Ofileanu and Topor, 2014; Pham, 2011) to support lean manufacturing and lean thinking (Kennedy and Brewer, 2005). Nguyen (2020) argues that lean accounting is the application of lean thinking to all financial and accounting processes and systems of the business.

Achagan et al. (2006) after studying 10 small and medium enterprises based in the East of England, pointed out four main factors affecting the implementation of lean production, including: leadership and management, finance, skills and expertise, and the culture of the organization. Leadership and management commitment are the most important factors in determining the success of a lean project. Nguyen et al. (2015) through the study of three lean projects have divided the important factors determining the successful implementation of lean production in lean manufacturing enterprises in Vietnam. Six aspects of the lean transformation model were presented in the study, including: Strategic Initiatives, Process Management, Change Management, Human Resource Management, Situation Management, and External Management. Research has also found that different factors have different effects but have not evaluated each factor in depth.

Many studies suggest that implementing lean is not an easy task (Achanga et al., 2006; Pirraglia et al., 2009; Nordin et al., 2010). Grasso (2006) divided the barriers to lean accounting into five categories: cultural, organizational, educational, professional, and personal. According to the author, culture is the biggest barrier. For organizational hurdles, a lean transformation of accounting must begin with the integration of accounting into manufacturing operations and have accountants participate in lean and Kaizen training to avoid the separation of the accounting department from other departments. Educational barriers are accounting training programs that are oriented towards public accounting, financial reporting, and auditing. The lack of lean accounting references is also a factor of educational barriers. The professional hurdles are the professional accounting certifications that contribute to the direction of the educational process focusing on financial accounting, orientation of financial statements. The personal barrier is that accountants can resist change for fear of the unknown. By way of training and self-selection, accountants may not like risk and change more than others. Accountants have reason to be apprehensive about a lean switch. They may be afraid of losing influence or stature. The final hurdle, accounting can have a bias for complexity and detail. Stenzel (2007) points out five factors that lead to the implementation of lean accounting failure, namely: people (unwillingness or fear of change, fear of losing jobs, fear of failure of individuals, fear of failure of business, fear of loss of reputation); machinery, materials and methods (enterprise resource planning systems, independent accounting information systems, mandatory non-financial data are not collected), measures and environment. In a quantitative study by Darabi et al. (2012), four groups of factors including cultural, technical, organizational and economic are considered barriers to the implementation of lean accounting in factories. Research results have shown that technical factors have the highest obstacles in the implementation of lean accounting in manufacturing companies and the lowest economic factors. Cultural factors include: the role of leadership, tactical attitudes, inappropriate reward procedures, resistance of managers, employees and even customers. The components of the technical barrier in this study include not using lean as a manufacturing strategy, not using general-purpose machinery, not using production systems in a timely manner and without warehouses as well as lack of awareness of lean systems by senior leaders and employees. Meanwhile, Mc Vay et al. (2013) only mentioned two barriers. The first is that most people prefer stability and resist change. They are afraid of the unknown, and they are able to cope with what they are used to, even if they know it may not be their best alternative. The second is a lack of knowledge or training on how to make an accounting transition.

Kumar and Kumar (2014) studied the barriers of lean manufacturing at 47 large and medium-sized manufacturing companies in India. This study looked at companies that are in the process of implementing lean manufacturing or have successfully adopted lean manufacturing systems. The seven main barriers of lean manufacturing deployment include: management, resources, knowledge, conflict, employees, finance, past experience. The results of the study by the average method show the level of resistance of the barriers from low to high as follows: management, knowledge, conflict, finance, employees, resources and past experience. Salonitis and Tsinopoulos (2016) classified barriers into four groups: financial, related to senior management, related to the workforce, and other barriers. Lodgaard et al. (2016) studied in-depth case studies at a manufacturing company in Norway for two years on barriers to successful lean implementation. Barriers include: Management, lean organization, lean tools and practices, and knowledge. Research shows that employees at different levels in a company notice different lean barriers. Top managers attribute limited success to barriers associated with the tool and lean practices. Workers mainly point out the challenges related to management. Middle managers acknowledge there are many barriers but mostly emphasize that roles and responsibilities are not defined and that best practice tools have not been selected. Nguyen et al. (2017) focused on identifying critical barriers/ difficulties and exploring the source of barriers/ difficulties for successful lean implementation at manufacturing companies in Vietnam. The study found seven major barriers to lean implementation success - leaders, employees, workplaces, resources, operational processes, customer relationships, and supplier relationships. Leadership barriers are considered the most important and influential in lean implementation.

From another perspective, Turesky and Connell (2010) studied the reasons for the failure to achieve the sustainability of lean manufacturing at a company in Northern New England. The authors proposed a four-stage model affecting lean project sustainability: set-up, preparation, implementation, and sustainability. The factors that affect leaning have been considered in stages and it is assumed that the factors in each stage interact with each other and should not be considered separately. A study of the implementation of lean manufacturing practices in the textile industry found Shah and Hussain (2016). The authors used survey methods to collect data from several Pakistani textile companies. Study results show that lean manufacturing practices have a significant relationship with scale. Larger organizations have used more lean manufacturing practices than small and medium-sized organizations. In addition, based on the literature review, ten factors hindering the implementation were identified and included in the questionnaire. Statistics have shown that in noncompliant companies, the four main barriers are: employee resistance, lack of communication, company culture, and lack of understanding. On the other hand, companies are transitioning to lean production systems where company culture, employee resistance, lack of communication, and a lack of understanding to implement lean production are key factors. For lean companies, a lack of communication is identified as the main barrier to successful implementation of a lean manufacturing system.

In 2021, Rehman et al., those factors include: technology gap, fear of unemployment in workers, current status of employees, fear of not knowing, change in reporting structure, skill gap, lack of appropriate communication, fear of people with machines, social disconnect, out-of-scope exposure, fear of managerial change, increasing factors of accountability, unhealthy behavior, the value of unknown technology, unknown ways to use technology, lack of uniformity in technology, technology related to too many paperwork, technology that creates too many jobs, technology abuse, high technology costs, technology that is a threat to personal freedom, technology that is different from work processes and procedures has been established, technology will have a negative impact on teamwork and collaboration, bad experience with technology in the past, lack of leadership/support for innovation, level of comfort - the effect of disruption, time to make changes and adjustments, understanding and ability to perform, budget priorities, difficulty/capacity/training time, resistance to learning new technology, stressful/overloaded work, cost, evidence of value, reliability, lack of clear scope, weak motivation to change, lack of money, skepticism in rank, high workforce turnover, little personal empowerment, use of relationships, insufficient knowledge of leanness and inadequate management skills. Sakataven et al. (2021) reviewed the literature and found fifteen barriers to lean implementation and by using the outputs of Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) and Impact Matrix Cross-Referencing Multiplication (MICMAC) analyses, the study classified 15 barriers into 10 levels. Where, “Roles and Responsibilities not defined in Lean Implementation” at level 1 ( the lowest impact level). The most important barriers are “Lack of long-term commitment to change and innovation” and “Personal Attitudes” (level 10). Some levels have many barriers. The study suggests that such classification helps organizations understand the motivating power and dependency of each barrier. This is important because motivation will determine the impact of a successful lean implementation. Barriers should also be addressed along with consideration of other barriers at the same level.

3. Theoretical framework and Methodology

3.1. Theoretical framework

Contingency theory is also known as random theory. This theory proposes that an effective process and structure of the enterprise are uncertainty in the context of the enterprise (Waterhouse and Tiessen, 1978). This theory asserts that the effective operation of the enterprise depends on the degree of conformity of the enterprise structure with previous contingencies (Mullins, 2013) According to Chenhall et al.(1981), environmental factors and internal random factors such as technology, scale, and structure have a significant impact on business processes and decisions. An lean accounting system suitable for a business depends on the characteristics of the business and the environment it is operating in. This shows that it is not possible to build a model that is a template that applies to all enterprises, but at the same time must be consistent with the organization structure, enterprise size, production technology and organization plan in each stage. Furthermore, there is no one lean accounting model that survives through different stages. This means that the construction of an effective lean accounting system must be suitable for each business, for the internal and external environment in which the business is operating.

Diffusion of innovations theory - DOI has been used by Rogers (2003) to describe the processes of change and the implementation of new techniques/methods in the organization. The theory holds that situational factors such as: business strategy, organizational culture, organizational structure, characteristics of innovation, communication channels, and environmental factors, etc. can influence the spread of innovation in the organization (Al-Omiri and Drury, 2007; Askarany and Smith, 2008; Askarany, 2012).

Cost-benefit analysis theory stated that the benefits derived from the accounting information provided must be considered in relation to the cost used to generate and provide that information. In general, the benefits from accounting information that can serve users: are related parties, investors and even the enterprise itself; and the costs are paid by the person who reports the accounting information but, in general, this cost is determined by society. Therefore, it is always necessary to consider and balance this relationship to ensure that the cost of creation does not exceed the benefits (Vu, 2010).

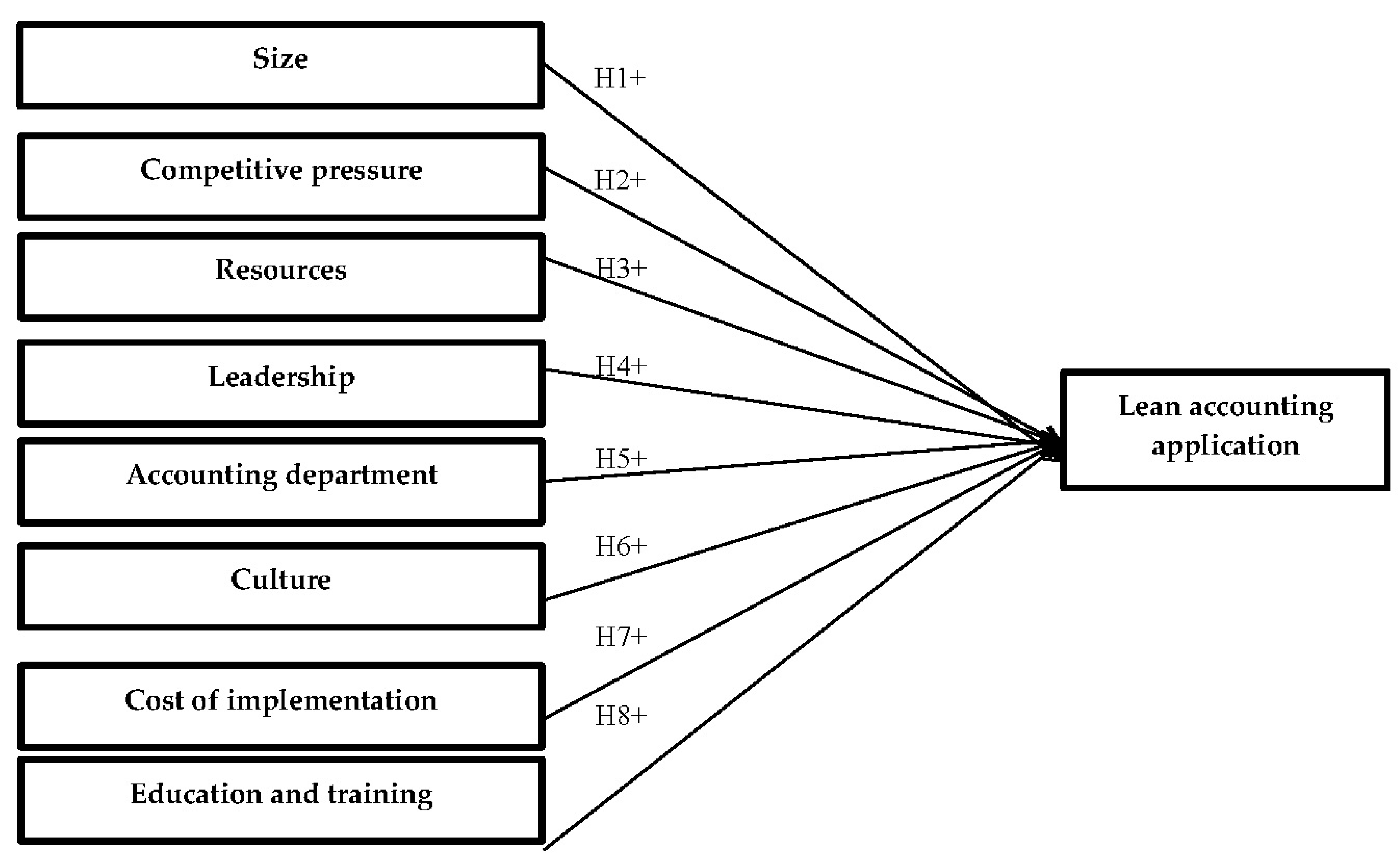

2.2. Hypothesis Development

From the background theories and overview of previous studies on the factors affecting or hindering the application of lean accounting in general enterprises and tailor-made enterprises in particular. The article (We) builds an initial research model including08 independent variables. From the research model that is expected to combine with the discussion and agreement with the experts, the authors propose 08 research theories, including:

Hypothesis H1 – Size has a positive relationship with the application of lean accounting at garment firms

Size of the enterprise can be determined by many measures such as revenue, capital, number of employees, etc. (Chenhall, 2003). In addition, according to the regulations on determining the size of small and medium-sized enterprises in Article 5 of Decree 80/2021/ND-CO issued on August 26, 2021 of the Government of Vietnam, the size of enterprises is determined according to 3 criteria: the number of employees participating in social insurance annually, the total revenue of the year (determined on the financial statements of the preceding year) and the total capital of the year (determined in the balance sheet shown on the financial statements of the preceding year). The inspection results of Tran (2015) show that the size factor with 3 observed variables: revenue, number of employees, number of departments and branches has a positive impact on the ability to apply management accounting in small and medium enterprises in Vietnam.

Hypothesis H2 – Competitive pressure has a positive relationship with lean accounting application at garment firms

Competition is something that any business faces, especially in the context of the current market economy and deep integration. In fact, in order to survive and develop, along with the increase of competitive pressure, enterprises also increased the use of more modern methods and tools of management and accounting (Doan, 2016). In addition, the study of Ngo (2021) when examining the correlation of competitive pressure factors with 3 observed variables (competitive in selling products and services in the market; competitive in buying materials; competitive in recruiting high-skilled workers) has a positive effect on the use of performance measures of manufacturing firms.

Hypothesis H3 - Resources have a positive relationship with lean accounting application at garment firms

Resources are indispensable for performing any activity. This is a factor that can affect the application of lean accounting in Vietnamese garment enterprises. The study by Darabi et al. (2012) used three variables for the resource factor: human resources, financial resources and time.

Hypothesis H4 - Leadership has a positive relationship with lean accounting application at garment enterprises

Leadership has the greatest influence and decisive role in all business operations, so the leadership factor has a great impact on the application of lean accounting. Perceptions of lean accounting, supportive attitudes, or motivational measures can all influence lean accounting adoption (Rehman et al., 2021; Grasso, 2006; Stenzel, 2007; Mc Vay et al., 2013). The study used five variables to measure leadership factors: commitment to long-term lean of leadership, awareness of lean accounting of leadership, attitude in favor of lean accounting adoption and measures to promote lean accounting adoption of leadership. In addition, the same viewpoint as the research results of Rehman et al. (2021) shows that accounting staff may not want to switch to lean accounting due to fear of losing their jobs, the proposal to add 1 observation variable is the leader's commitment to the rights of accounting staff.

Hypothesis H5 – Accounting department has a positive relationship with the application of lean accounting at garment firms

Accountants who are directly involved in the process of implementing lean accounting, therefore, applying lean accounting to Vietnamese garment enterprises are naturally affected by this factor. The barriers belonging to accounting staff have been pointed out by Mc Vay et al. (2013), Stenzel (2007), Grasso (2006), Rehman et al. (2021), Carnes and Hedin (2005) including: Lack of knowledge, skills and capacity to implement lean accounting, Unwillingness or fear of change, Fear of losing jobs, Fear of losing influence, Fear of not learning new technologies, Not understanding the production and business processes of firms,... Since then, the experts have agreed that the accounting department affects the application of lean accounting at Vietnamese garment enterprises and identified four observed variables: knowledge, skills and capacity to implement lean accounting of accounting staff; supportive attitude of accounting staff; The understanding of accounting staff about the production and business processes of firms and the connection between accounting department and other departments.

Hypothesis H6 - Culture has a positive relationship with lean accounting application at garment enterprises

Corporate culture is a factor that needs to go through a long process of formation and development to be able to build. Therefore, it could not be changed easily, and it will take a lot of time to do that. It helps to shape the working environment and habits of people. All activities of enterprises are also affected by many factors from this platform. Many studies have shown that the failure of enterprises to build a lean corporate culture leads to the implementation of lean failure. Corporate culture of command and control, less employee empowerment will be a barrier to lean accounting (Grasso, 2006, Rehman et al., 2021). The lean culture with the characteristics of cooperation, continuous improvement and personal empowerment will also make the accounting department not separate from other departments, thereby making the accountants understand the actual situation of the business and not consider it to be the work of others or unrelated to them. Since then, the study agreed that business culture can affect lean accounting adoption at Vietnamese garment firms and identified three observation variables under this factor: collaboration culture, continuous improvement culture and employee empowerment culture.

Hypothesis H7 – Cost of implementation has a positive relationship with the application of lean accounting at garment firms

To decide whether to apply lean accounting or not, businesses often consider the cost of implementation. This is a factor affecting the application of lean accounting in Vietnamese garment firms. Tran (2015) concluded that low costs have a positive impact on the application of management accounting in small and medium enterprises in Vietnam. Similarly, high costs are considered a barrier for lean accounting at Parkistan garment enterprises (Rehman et al., 2021). The study has identified 3 observed variables of the implementation cost factor (low): facilities costs, accounting staff costs, consultant costs.

Hypothesis H8 - Education and training have a positive relationship with lean accounting application at garment firms

Education and training is factors both inside and outside enterprises, education and training directly affect the quality of human resources of enterprises (Carnes and Hedin, 2005; Grasso, 2006; Rehman et al., 2021). In the context that lean accounting in Vietnam is still a relatively new content, little known, if lean accounting is not taught or guided, it will cause many difficulties to the application of lean accounting in Vietnamese garment firms. The observed variables are: Educational institutions, teaching training on lean accounting, enterprises organizing training programs on lean accounting, Guidance documents on lean accounting.

The research model has been designed in

Figure 1, below

:

3.2. Research methodology

Based on the literature review and grounded theories, we have gathered the determinants affecting the application of green accounting. We conduct in-depth interviews to redefine factors and find new determinants from 12 experts who are experienced and knowledgeable about Lean accounting in garment firms. Then test the factors and models developed from the data collected through studies around the world to determine if they are really appropriate in the current context. Then, we use quantitative research methods and questionnaire surveys to test hypotheses and models about factors affecting the application of lean accounting in Vietnamese garment firms.

The questionnaire survey for the study is divided into three parts: part 1: Introduction to the topic, part 2: Overview of the firm and respondents, and part 3: Questions related to determinants influencing the application of lean accounting in Vietnamese garment firms.

Survey subjects are firm managers, chief accountants, accountants of garment firms in Vietnam with 242 questionnaire surveys collected, during the period from 03/2022 to 11/2022. The data was collected in two ways: by direct collection, to the company giving the questionnaire directly to the subjects surveyed, and by collecting data from the oRSine design questionnaire on the Google form that sent the questionnaire via email and zalo.

After obtaining data from the questionnaire surveys, the research team will eliminate the unsatisfactory questionnaire surveys, then perform data entry for analysis:

Step 1: Test the scale using Cronbach's Alpha (CR) to assess the quality of the scales.

Step 2: Exploratory factor analysis: This step aims to reduce the set of observed variables into factors so that they are more meaningful. The article uses KMO, Bartlett and variance testing to determine the representative scale system.

Step 3: Linear regression analysis: use the tests of the regression coefficients, the appropriate level of the model and the correlation to determine the factors and the level of influence of the factors.

Step 4: Analyze the residue: use the Histogram, Normal P-P Plot and Scatterplot to check if the hypotheses are violated.

4. Results

4.1. Cronbach's Alpha test results of the scales

The specific results of testing the reliability of Cronbach's Alpha scales are presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

The test results show that all scales have Cronbach's Alpha coefficient > 0.6 and are quite high, the lowest is 0.770 and the highest is 0.941. In addition, the total variable correlation coefficients are > 0.3. Therefore, it can be confirmed that the scales of the study are reliable and can be used to analyze the discovery factor in the next step.

4.2. Exploratory factor analysis

* EFA factor analysis for independent variables

Processing results from SPSS software for independent variables are as follows:

Table 3 shows that KMO = 0.856 > 0.5 so factor analysis is appropriate. Sig. (Bartlett's Test) = 0.000 (sig.<0.05) shows that the observed variables involved in the EFA analysis are correlated.

Source: Data analysis results from SPSS 26.0.

Table 4 shows that there are 8 factors extracted based on Eigenvalue 1.148 >1 or 8 factors that summarize the information of 27 observed variables into EFA in the best way. The total variance of these factors extracted is 70.867% >50%. Thus, the 8 factors cited explained 70.867% of the data variation of 27 observed variables participating in EFA.

The loading factor of the observed variables in the rotation matrix is > 0.5 (

Table 5) or these observed variables are all significant contributors to the model.

* EFA analysis for the dependent variable

The processing results from SPSS software for the dependent variable are as follows:

Table 6 shows KMO = 0.937 > 0.5 so factor analysis is appropriate. Sig. (Bartlett's Test) = 0.000 (sig.< 0.05) shows that the observed variables involved in the EFA analysis are correlated.

Table 7 shows that there is a factor extracted based on Eigenvalue 6,128 >1. The extracted variance is 68.094% >50%.

Table 8 shows that the loading factor of the observed variables in the rotational matrix is > 0.5 or these observational variables are all significant contributors to the model.

Source: Data analysis results from SPSS 26.0.

From the results of exploratory factor analysis of toxic variables and dependent variables, the research has the groups of factors representing the following variables:

Scale Factor – SZ: SZ1, SZ2, SZ3

Competitive Pressure Factor – CP: CP1, CP2, CP3

Resource Factor – RS: RS1, RS2, RS3

Leadership Factor – LD: LD1, LD2, LD3, LD4, LD5

Factor Accounting Department – AD: AD1, AD2, AD3, AD4

Cultural Factors – CT: CT1, CT2, CT3

Implementation Cost Factor – CO: CO1, CO2, CO3

Education and training factors – ET: ET1, ET2, ET3

Factors Applied Lean Accounting – LA: LA1, LA2, LA3, LA4, LA5 LA6, LA7, LA8, LA9

4.3. Correlation analysis

Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine the strong linear correlation between the dependent variable (LA) and the independent variables (SZ, CP, RS, LD, AD, CT, CO and ET) and early identification of the multicollinearity phenomenon when the independent variables are also strongly correlated with each other.

- Correlation between dependent variables and independent variables: The Pearson correlation analysis table (

Table 10) shows that the correlation coefficients are 1, 0.569, 0.463, 0.554, 0.671, 0.544, 0.480, 0.514, 0.480 or all 8 independent variables in the proposed model are strongly correlated with the dependent variable (Hoang and Chu, 2008).

- Correlation between independent variables:

Table 9 also shows that if all sig. between independent variables are less than 0.05 minus sig. between variables CP and ET. However, the Pearson correlation coefficient between independent variables is less than 0.7. Therefore, it is not yet sufficient to conclude between variables that are likely to occur multicollinearity (Dormann et al., 2013).

Table 9.

Pearson Correlation Analysis.

Table 9.

Pearson Correlation Analysis.

| Correlations |

|---|

| |

LA |

SZ |

CP |

RS |

LD |

AD |

CT |

CO |

ET |

| LA |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

.569**

|

.463**

|

.554**

|

.671**

|

.544**

|

.480**

|

.514**

|

.480**

|

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

| N |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

| SZ |

Pearson Correlation |

.569**

|

1 |

.377**

|

.367**

|

.485**

|

.188**

|

.181**

|

.164*

|

.147*

|

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

|

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.003 |

.005 |

.011 |

.022 |

| N |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

| CP |

Pearson Correlation |

.463**

|

.377**

|

1 |

.397**

|

.422**

|

.232**

|

.193**

|

.156*

|

.101 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

.000 |

|

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.003 |

.015 |

.115 |

| N |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

| RS |

Pearson Correlation |

.554**

|

.367**

|

.397**

|

1 |

.483**

|

.354**

|

.225**

|

.244**

|

.215**

|

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.001 |

| N |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

| LD |

Pearson Correlation |

.671**

|

.485**

|

.422**

|

.483**

|

1 |

.298**

|

.239**

|

.249**

|

.254**

|

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

| N |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

| AD |

Pearson Correlation |

.544**

|

.188**

|

.232**

|

.354**

|

.298**

|

1 |

.381**

|

.349**

|

.383**

|

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

.003 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

| N |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

| CT |

Pearson Correlation |

.480**

|

.181**

|

.193**

|

.225**

|

.239**

|

.381**

|

1 |

.416**

|

.438**

|

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

.005 |

.003 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

.000 |

.000 |

| N |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

| CO |

Pearson Correlation |

.514**

|

.164*

|

.156*

|

.244**

|

.249**

|

.349**

|

.416**

|

1 |

.404**

|

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

.011 |

.015 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

.000 |

| N |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

| ET |

Pearson Correlation |

.480**

|

.147*

|

.101 |

.215**

|

.254**

|

.383**

|

.438**

|

.404**

|

1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

.022 |

.115 |

.001 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

| N |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

242 |

| **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). |

| *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). |

4.4. Multivariate regression analysis

The processing results from SPSS software are obtained as follows:

Table 10.

Model Summaryb.

Table 10.

Model Summaryb.

| Model |

R |

R Square |

Adjusted R Square |

Std. Error of the Estimate |

Durbin-Watson |

| 1 |

.873a |

.762 |

.754 |

.27610 |

2.190 |

| a. Predictors: (Constant), ET, CP, SZ, CO, AD, RS, CT, LD |

| b. Dependent Variable: LA |

Source: Data analysis results from SPSS 26.

Table 10 shows the results of the conformity assessment of the multivariate regression model. R = 0.873 indicates a high degree of correlation. R

2 correction = 0.754 indicates that the independent variables included in the regression analysis explain 75.4%% fluctuations of the dependent variable, the remaining 24.6% is due to variables outside the model and random error. This result also indicates the statistical value of the Durbin-Watson test = 2.19

≈ 2, which is between 1 and 3, so the result does not violate the first-order self-correlation assumption (Field, 2009).

Anova analysis (

Table 11) indicates the relevance of the regression equation to the data. The test results show that F = 56.856, sig. = 0.000 < 0.05. Prove that R2 is non-zero overall. This means that the linear build regression model is suitable.

Source: Data analysis results from SPSS 26.

Correlation coefficient analysis (

Table 12) shows that the value of sig. of all variables is < 0.05 or these variables are statistically significant, all affect the dependent variable. All eight theories are accepted. Regression coefficients (B and β) in all 8 independent variables are positive, meaning that all 8 independent variables have a positive effect on the dependent variable.

In addition, VIF variance magnification coefficients of all independent variables in the model were < 2 indicating that the data did not violate the multicollinearity assumption or that multicollinearity between independent variables occurred (Hair et al., 2009).

4.5. Analysis of residuals

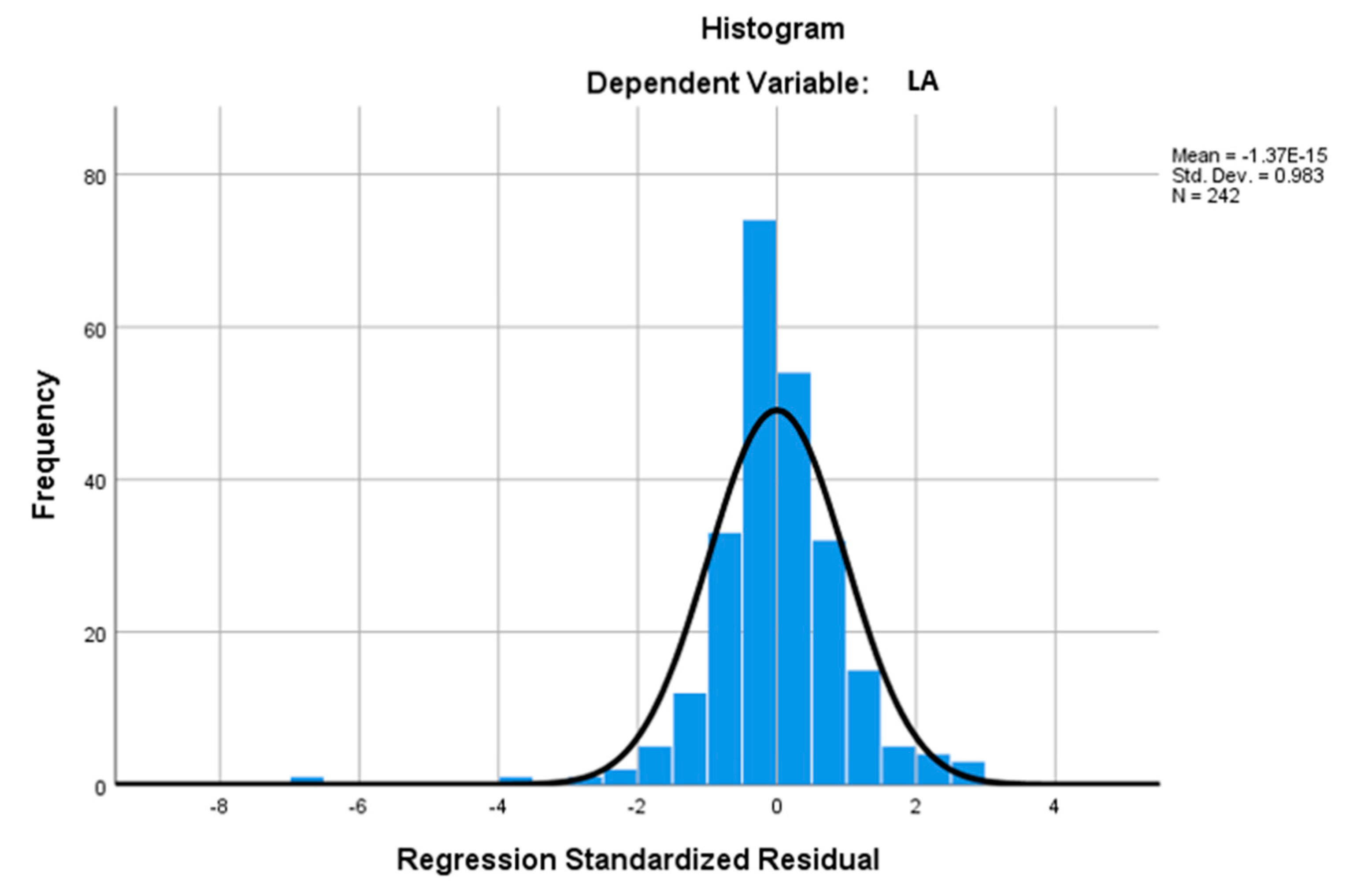

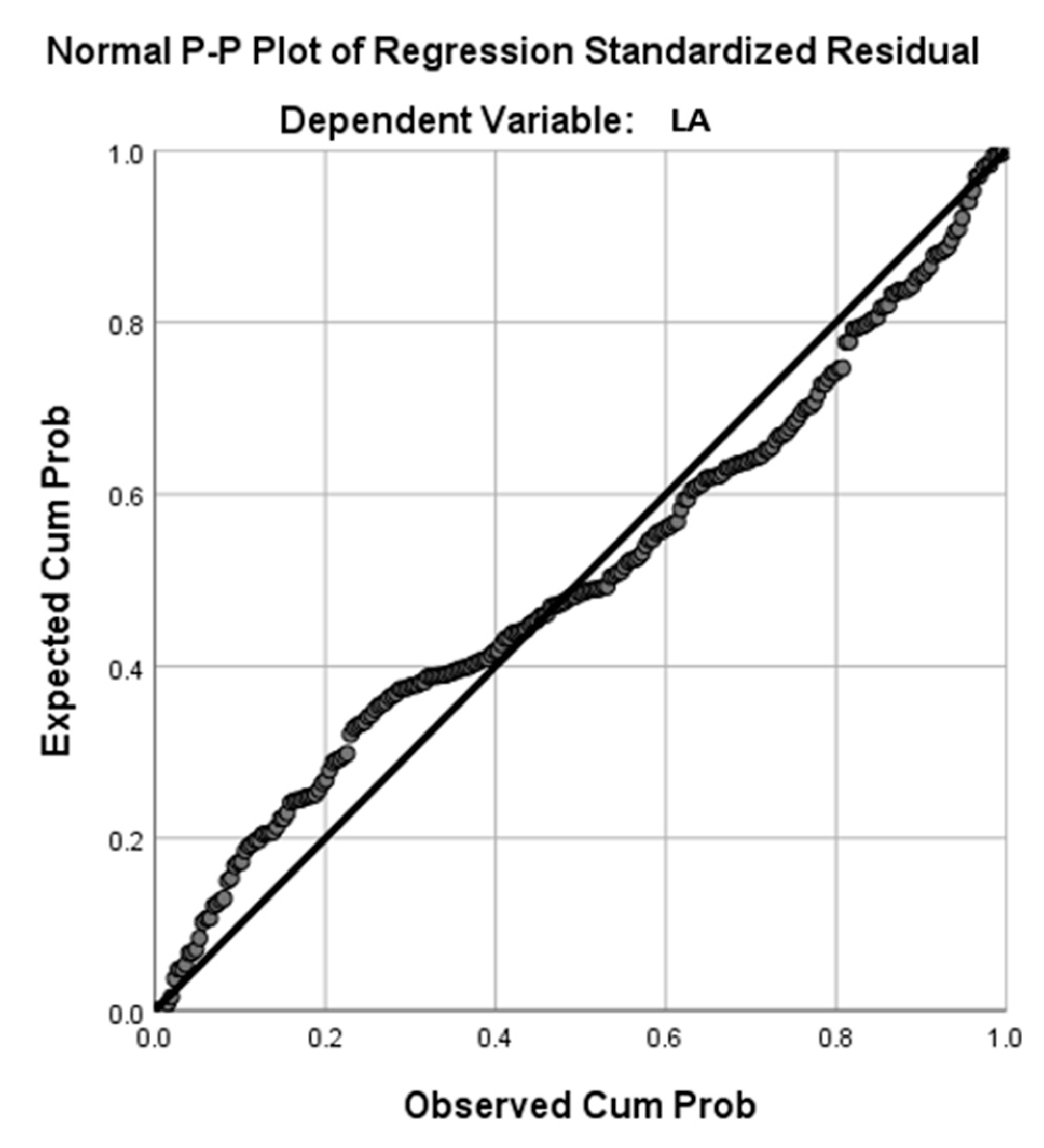

Test of the standard distribution assumption: Looking at

Chart 1, it could be seen that the normalized residue is distributed according to the bell curve, the shape of the standard distribution. In addition, the mean is 1.37E-15 approximately = 0, and the standard deviation is 0.983 approximately = 1. In addition, the Normal P-P Plot (

Chart 2) shows that the observed values and expected values are all around the diagonal, with no major deviations from the diagonal. This shows that the normalized residue approximates the normal distribution. Thus, it is assumed that the standard distribution of the balance is not violated.

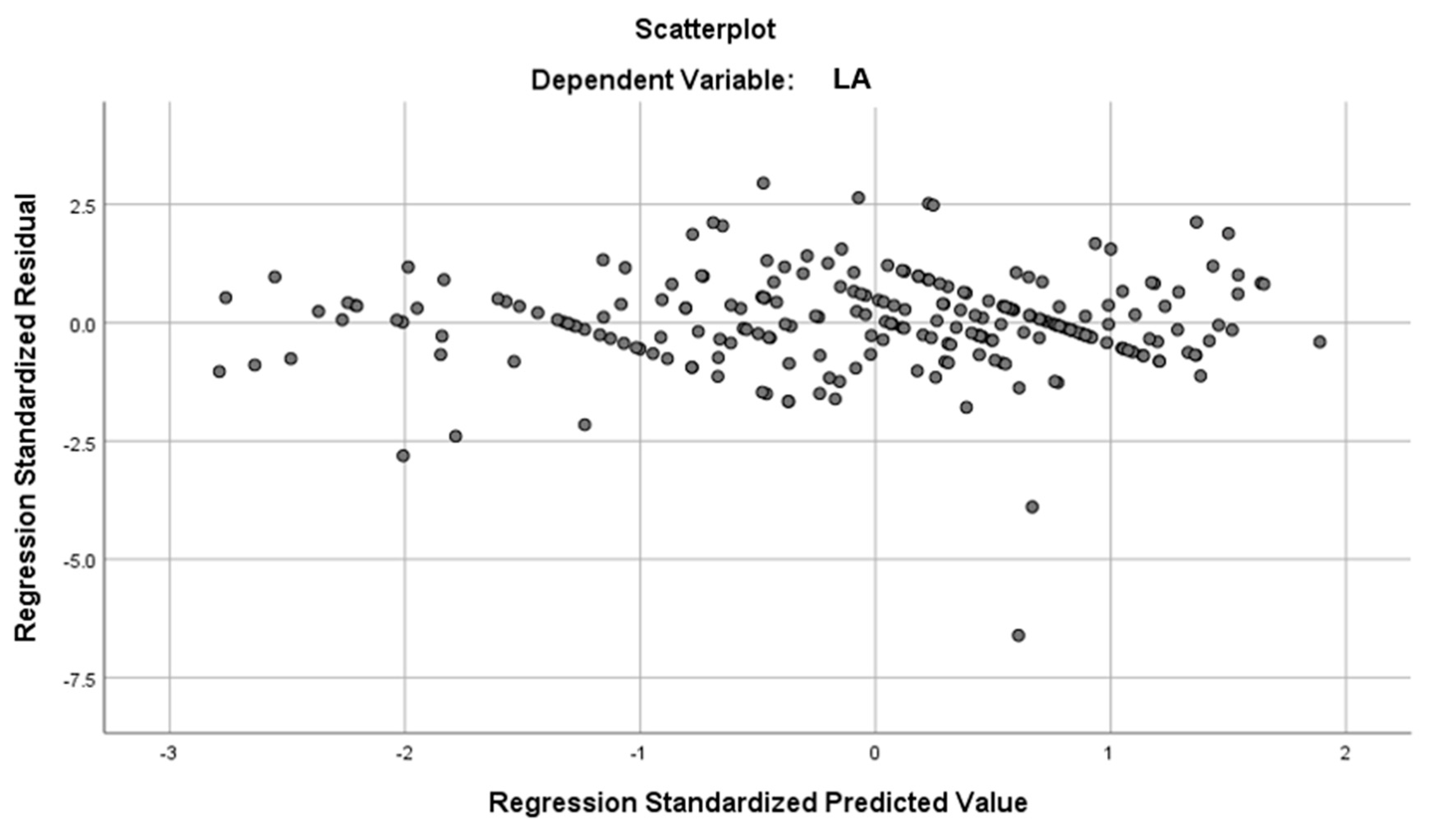

Test of linear contact and constant variance consumptions

To test these assumptions, the research used the Scatterplot scatter chart. Looking at

chart 3, it could be seen that the data points are concentrated around the zero point and tend to form a straight line. Thus, the assumptions of linear contact and constant variance of residual are not violated.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

The above results show that the scales of the study are reliable to use for exploratory factor analysis, dependent variables and independent variables are strongly correlated with each other, there is no multicollinearity phenomenon between the dependent variables, the observed variables are meaningful to contribute to the model, and the assumptions in the regression analysis are not violated. All 8 factors representing 27 observed variables have a favorable influence on the application of lean accounting in Vietnamese garment enterprises, the level of influence of the factors is different and is arranged in ascending order as follows:

5.1. Leadership factor

Leadership factor has a positive relationship with lean accounting, which is also the most powerful of the eight factors. In the context that other factors are unchanged, the leadership factor increases by 1 point, the ability to apply lean accounting increases by 0.293 points. Among the observation variables of the leadership factor, "Measures to promote the application of lean accounting by business leaders" is rated as having the greatest influence, followed by "The attitude of supporting lean accounting of business leaders", "Commitment to ensuring the rights of accounting staff of business leaders" and finally "Leadership awareness of lean accounting". This result is consistent with the research of Darabi et al. (2012) and Rehman et al. (2021) which argues that ignorance or disapproval of business leaders will hinder the adoption of lean accounting. This is also consistent with the fact that leadership is the highest level of decision making, has the greatest influence on all activities of the business, so leadership has a great influence on the application of lean accounting of the business. In addition, this result also explains the link between the fact that Vietnamese garment enterprises have not applied lean accounting with the fact that top managers (often with little accounting expertise) and even senior accountants do not really understand this new type of accounting.

5.2. Size factor

Size factor has a positive relationship with the application of lean accounting. The larger the firm, the higher the ability to apply lean accounting. In the context that other factors are stable, the size factor increases by 1 point, the ability to apply lean accounting increases by 0.241 points. In which, the observation variable is the most appreciated capital source, followed by the number of employees and finally the Revenue. This result is compatible with the survey results that show that firms that have used lean accounting are only large and medium-sized. The larger the firm, the higher the management requirements, the stronger the resources, the higher the ability to apply lean accounting..

5.3. Cost of implementation factor

Cost of implementation factor has positive relationship with a. The higher the cost of implementing lean accounting is, the higher the likelihood of applying lean accounting is. In the context that other factors are unchanged, the cost factor increases by 1 point, the ability to apply lean accounting increases by 0.192 points. Among the observed variables of this factor, consultant cost is the highest, followed by accounting staff cost and finally facilities cost. This result is consistent with the research of Darabi et al. (2012), Rehman et al. (2021) who argued that high cost of technology hinders the adoption of lean accounting.

5.4. Accounting department

Accounting department factor has a positive relationship with the application of lean accounting. In case that other factors are unchanged, the factor of the Accounting department increases by 1 point, the ability to apply lean accounting increases by 0.186 points. Among the observed variables of this factor, supportive attitude of accounting staff is rated as the highest, followed by the accounting staff's knowledge, skills and capacity to perform lean accounting and finally, the understanding of accounting staff about the production and business processes of the firm. This result is consistent with the research of Grasso (2006), Darabi et al. (2012), Mc Vay et al. (2013), Rehman et al. (2021) who believed that ignorance, protest, fear of losing a job, incompetence,...of corporate accounting staff will obstruct the application of lean accounting.

5.5. Education and training factor

Research results show that Education and training factor has a positive relationship with the application of lean accounting. In the context of other factors unchanged, the factor of Education and training increased by 1 point, the ability to apply lean accounting increased by 0.137 points. In particular, the observation variable "The teaching of lean accounting at educational and training institutions" has the highest influence, followed by "The guidance documents on lean accounting" and finally "The training programs on lean accounting of firms". This result is consistent with that of the research of Carnes & Hedin (2005), Grasso (2006) said that lack of education and training obstructs lean accounting. In Vietnam, the curriculum of schools and institutes at all levels often focuses on teaching financial accounting and traditional management accounting. The same situation occurs with vocational certification training programs of the accounting industry such as Chief accountant certification, COA, ACCA, CMA, ... lean accounting is almost not taught, if any, it is just introductory and comparatively brief. This is the main cause leading to the lack of knowledge of lean accounting. In addition, firms also rarely have training programs in lean accounting and compared to traditional accounting documents, the documents of lean accounting is also relatively modest. The Vietnamese materials only have some articles and conference proceedings. Thus, the more education and training programs as well as guidance documents on lean accounting, the higher the ability to apply lean accounting.

5.6. Resources factor

Resources factor has a positive relationship with lean accounting application. Supposing that other factors are unchanged, the Resources factor increases by 1 point, the ability to apply lean accounting increases by 0.120 points. In which, the observation variable Human resources is evaluated to be the highest, followed by Time and finally Financial resources. This result is related to that of the research of Darabi et al. (2012), Rehman et al. (2021) stated that the lack of resources hinders the adoption of lean accounting. In other words, the more resources a business devotes to accounting, the higher its ability to apply lean accounting.

5.7. Culture factor

Cultural factor has a reversible relationship with lean accounting application. In the context that other factors stay the same, the Resource factor increases by 1 point, the ability to apply lean accounting increases by 0.110 points. In particular, the observation variables CT1 "Collaborative culture" and CT2 "Continuous improvement culture" have the highest average (3,335) and the lowest CT3 "Employee empowerment culture" with an average of 3.31. This result is parallel with the research of Grasso (2006), Rehman et al. (2021) who thought that a lean corporate culture hinders the adoption of lean accounting. This result means that the more you build a lean corporate culture (Collaborative, Continuous improvement, and Employee empowerment), the greater your ability to apply lean accounting is.

5.8. Competitive pressure factor

Competitive pressure factor has a positive correlation with lean accounting application. This is the factor with the lowest impact. In the condition that other factors remain unchanged, the competitive pressure factor increases by 1 point, the ability to apply lean accounting only increases by 0.093 points. In particular, the observation variable CP3 "Competition in selling products" has the highest average (3.40), followed by CP1 "Competitive in buying materials" with an average of 2.40 and finally CP2 "Competitive in selling products" with an average of 2.37. Thus, the more competitive the business environment in which firms operate, the higher the ability to apply lean accounting.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- Achanga, P.; Shehab, E.; Roy, R.; Nelder, G. Critical success factors for lean implementation within SMEs. Journal of manufacturing technology management 2006, 17, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omiri, M. The diffusion of management accounting innovations: a study of the factors influencing the adoption, implementation levels and success of ABC in UK companies. Ph.D Thesis, University of Huddersfield, United Kingdom, 2003. Available online: http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/4612/1/411890.pdf.

- Arbulo-López, P.R.; Fortuny-Santos, J. An accounting system to support process improvements: Transition to lean accounting. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management 2010, 3, 576–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, V. , and Soral, G. Conceptual issues in lean accounting: A review. IUP Journal of Accounting Research & Audit Practices 2017, 16, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Askarany, D.; Smith, M. Diffusion of Innovation and Business Size: A Longitudinal Study of PACIA. Managerial Auditing Journal 2008, 23, 900–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosnahan, J.P. Unleash the Power of Lean Accounting. Journal of accountancy 2008, 206, 60–62,64,66, URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v4-i4/793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnes, K.C.; Hedin, S.R. Accounting for Lean Manufacturing: Another Missed Opportunity? Management Accounting Quarterly 2005, 7, 28–35, Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/accounting-lean-manufacturing-another-missed/docview/222802565/se-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chenhall, R.H. Management control systems design within its organizational context: findings from contingency-based research and directions for the future. Accounting, Organizations and Society 2003, 28, 127–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, J.E.; Fium, O.; Adams, E. Real numbers: Management accounting in a lean organization,; Managing Times Press: Durham, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Doan, N.P.A. . Factors Affecting the Use and Consequences of Management Accounting Practices in A Transitional Economy: The Case of Vietnam. Journal of Economics and Development 2016, 18, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, C.F. , Elith, J., Bacher, S., Buchmann, C., Carl, G., Carré, G., Marquéz, J.R.G., Gruber, B., Lafourcade, B., Leitão, P.J. and Münkemüller, T. 2013. Collinearity: a review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 2003, 36, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, R.; Moradi, R.; Toomari, U. Barriers to implementation of lean accounting in manufacturing companies. International Journal of Business and Commerce 2012, 1, 38–51, Retrieved from https://www.ijbcnet.com/1-9/IJBC-12-1804.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. 3rd Edition, Sage Publications Ltd., London. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/24632540/Discovering_Statistics_Using_SPSS_Introducing_Statistical_Method_3rd_edition_2_.

- Grasso, L.P. . Barriers to lean accounting. Cost Management 2006, 20, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr., J. F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J. and Anderson, R.E. 2009. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th Edition, Prentice Hall. Retrieved from https://www.drnishikantjha.com/papersCollection/Multivariate%20Data%20Analysis.pdf. /: Prentice Hall. Retrieved from https.

- Hoang, T.; Chu, N.M.N. Analyze research data with SPSS; Hong Duc Press: Ho Chi Minh, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, F.A.; Brewer, P.C. . Lean accounting: what's it all about? Strategic Finance 2005, 87, 26–34, Retrieved from https://www.ame.org/sites/default/files/target_articles/06-22-1-Lean_Accounting.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Krafcik, J.F. Triumph of the lean production system. Sloan management review 1988, 30, 41–52, Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/docview/224963951?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Kumar, V. Barriers in implementation of lean manufacturing system in Indian industry: A survey. International Journal of Latest Trends in Engineering and Technology 2014, 4, 243–251, Retrieved from http://www.ijltet.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/33.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.K.O. Proposal to apply lean production – Lean – For the case of Saigon garment joint stock company 2. Journal of science, technology & food 05/ 2015, 2015, 142–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lodgaard, E.; Ingvaldsena, J.A.; Gammea, I.; Aschehouga, S. Barriers to Lean Implementation: Perception of Top Managers, Middle Managers and Workers. Procedia CIRP 2016, 57, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskell, B.H. Lean accounting for lean manufacturers. Manufacturing Engineering 125(6), 46-53. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/lean-accounting-manufacturers/docview/219714512/se-2. /: Retrieved from https, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Maskell, B.H.; Baggaley, B.L. Lean accounting: What's it all about? Target Magazine 2006, 22, 35–43, Retrieved from https://www.ame.org/sites/default/files/target_articles/06-22-1-Lean_Accounting.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Maskell, B.H.; Baggaley, B.; Grasso, L. Practical lean accounting: a proven system for measuring and managing the lean enterprise; CRC Press: New York, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Maskell, B.H.; Kennedy, F.A. . Why do we need lean accounting and how does it work? Journal of Corporate Accounting and Finance 2007, 18, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mize, J.H. Transitioning to a Lean Enterprise: A Guide for Leaders, Volume I, Executive Overview. Retrieved from https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/81896. /: from https, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, L. 2013. Management and Organisational Behaviour. Financial Times Prentice Hall, 7th ed. Retrieved from http://www.mim.ac.mw/books/Management%20&%20Organizational%20Behaviour,%207th%20edition.pdf.

- Ngo, T.T. 2021. Factors affecting the use of performance measures of Vietnamese manufacturing enterprises. Doctoral dissertation, National Economics University, Viet Nam.

- Nguyen, D.M.; Nguyen, D.N.; Le, A.T. Framework of Critical Success Factors for Lean Implementation in Vietnam Manufacturing Enterprises. VNU Journal of Science: Economics and Business 31(5E): 33-41. Retrieved from https://js.vnu.edu.vn/EAB/article/view/338. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.M.; Nguyen, D.N.; Le, A.T. Factors affecting the application of lean production methods in enterprises in Vietnam, Vietnam Journal of World Economics and Politics 2017, 12: 41-48. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/35600430/C%C3%81C_NH%C3%82N_T%E1%BB%90_T%C3%81C_%C4%90%E1%BB%98NG_%C4%90%E1%BA%BEN_VI%E1%BB%86C_%C3%81P_D%E1%BB%A4NG_PH%C6%AF%C6%A0NG_PH%C3%81P_S%E1%BA%A2N_XU%E1%BA%A4T_TINH_G%E1%BB%8CN_TRONG_C%C3%81C_DOANH_NGHI%E1%BB%86P_T%E1%BA%A0I_VI%C3%8AT_NAM.

- Nguyen, V.H. Applying lean accounting in enterprises and some recommendations. Review of Finance 1 (7/2020): 95-98. Retrieved from https://tapchitaichinh.vn/ap-dung-mo-hinh-ke-toan-tinh-gon-trong-doanh-nghiep-va-mot-so-de-xuat.html. /, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nordin, N. , Deros, B.M., and Abd Wahab, D. 2010. A survey on lean manufacturing implementation in Malaysian automotive industry. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology 2010, 1, 374–380. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, Q.H. Analysis of the lean production process and accounting features in the current lean accounting model. Retrieved from https://www.sav.gov.vn/SMPT_Publishing_UC/TinTuc/PrintTL.aspx?idb=2&ItemID=1705&l=/noidung/tintuc/Lists/Nghiencuutraodoi. /: from https, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pirraglia, A., Saloni, D., and Van Dyk, H. 2009. Status of lean manufacturing implementation on secondary wood industries including residential, cabinet, millwork, and panel markets. BioResources 4, 1341–1358. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26850232_Status_of_lean_manufacturing_implementation_on_secondary_wood_industries_including_residential_cabinet_millwork_and_panel_markets. /: Retrieved from https, 2009.

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Salonitis, K.; Tsinopoulos, C. Drivers and Barriers of Lean Implementation in the Greek Manufacturing Sector. Procedia CIRP. [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Ward, P.T. Lean Manufacturing: Context, Practice Bundles, and Performance. Journal of Operations Management 2003, 21, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenzel, J. Lean accounting: Best Practices for sustainalr intergration. John Wiley and Sons, Inc, Hoboken, New Jersey. .: and Sons, Inc, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofileanu, D.; Topor, D.I. Lean Accounting - An Ingenious Solution for Cost Optimization. The International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2014, 4, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, M.Z.; Malik, E.; Baig, S.A.; Rehman, H.; Hashim, M. Lean accounting awrareness: A qualitative study on lean accounting perception. International Journal of Management 2021, 12, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, K. A Comparative Analysis of Management Accounting Systems on Lean Implementation, Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee. Retrieved from https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3758&context=utk_gradthes. /, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.H. Exploring the Role of Standard Costing in Lean Manufacturing Enterprises: A Structuration Theory Approach. Management Accounting Quarterly 2012, 13, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.H.; Bargerstock, A. ‘Exploring the role of standard costing in lean manufacturing enterprises: a structuration theory approach’. Management Accounting Quarterly 2011, 13, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, M.H.S. & Bargerstock, A. 2011. Exploring the role of standard costing in lean manufacturing enterprises: A structuration theory approach. Management Accounting Quarterly 13, 47-60. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/exploring-role-standard-costing-lean/docview/2437890723/se-2. 2011; 13, 47–60.

- Shah, Z.A. and Hussain, H. 2016. An investigation of lean manufacturing implementation in textile sector of Pakistan. In Proceedings of the 2016 international conference on industrial engineering and operations management: 8-10. Retrieved from https://scholar.google.com.vn/scholar?q=An+investigation+of+lean+manufacturing+implementation+in+textile+sector+of+Pakistan&hl=en&as_sdt=0&as_vis=1&oi=scholart.

- Sakataven, R.S.; Syed, A.H.; Hisjam, M. Lean implementation barriers and their contextual relationship in contract manufacturing machining company. Evergreen Joint Journal of Novel Carbon Resource Sciences & Green Asia Strategy 2021, 8, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H. 2016. Factors affecting the application of management accounting in SMEs in Vietnam, Doctoral dissertation, University of Economics Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam.

- Turesky, E.F.; Connell, P. Off the rails: Understanding the derailment of a lean manufacturing initiative. Organization Management Journal 2010, 7, 110–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VCBS. 2022. Báo cáo nhanh ngành dệt may 9T.2022. Truy cập tại https://vcbs.com.vn/api/v1/ttpt-reports/download-with-token?download_token=49c97ab2-5d23-405a-b068-827d32be7dd7&locale=vi.

- Vu, H.D. Basic problems of accounting theory.; Labor Press: Ha Noi, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse, J.H.; Tiessen, P. A contingency framework for management accounting systems research. Accounting, organizations and society 1978, 3, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womack, J.P.; Jones, D.T.; Roos, D. The machine that changed the world: The story of lean production--Toyota's secret weapon in the global car wars that is now revolutionizing world industry. Free Press. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/35690909/The_machine_that_changed_the_world. /, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yahua Qiao. 2011. Instertate Fiscal Disparities in America. 1st ed. Routledge, New York. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).