1. Introduction

With the development of technology, the types of materials used in living spaces have also changed. But, even though many new materials have come out, wood is still preferred and encouraged because of its unique qualities. It will continue to be preferred due to its many advantages, such as its high resistance compared to its specific gravity, easy processing, good paint and varnish acceptance, good heat and sound insulation, aesthetic appearance, fast recycling to nature, renewable and carbon blocking material.

Wood is a naturally occurring material that is heterogeneous and anisotropic, and it has various growth defects. Wood material, which has been used since the early ages of humanity, is widely used in many sectors, such as construction, furniture, and automotive. Wood used as a building material undergoes a multi-stage classification and processing. In the process from wood to building components, the yield drops to 25-35% during processing [

1,

2].

The increasing use of wood, a biodegradable material, puts pressure on forests. In order to reduce this pressure, various wood-based panels are produced by utilizing lignocellulosic wastes. Wood-based panels (MDF, particleboard, CLT, LVL, glulam, plywood, etc.) are widely used in woodworks such as furniture, wooden structures, and flooring [

3,

4].

Plywood is one of the wood-based panel products that is manufactured at the highest volume. Plywood is produced by pressing the wood veneers under high temperature and pressure by stacking them on top of each other in such a way that the fiber directions are perpendicular to each other using a thermoset adhesive. Due to its improved dimensional stability, water-resistance properties, and high mechanical strength acquired via layered manufacturing, it is almost defect-free, available in large dimensions, different sizes, and grades ideal for all uses [

5,

6,

7,

8].

The strength of wooden building and furniture mainly depends on the mechanical properties of the materials they are produced, the type of fastener, the number, dimensions, etc. parameters. The performance of the fasteners is one of the most important factors influencing the quality of furniture construction. Today, especially in the furniture industry, numerous fasteners such as mechanical cam locking, screw-in, bolt-tightening, bracket, and hooks are used. Failure to do the proper fastening may result in reduced strength of the connection point and extend the assembly time. For this reason, fasteners with the fastest / easiest application and high connection strength should be selected [

9,

10,

11].

Screws are the most commonly used fasteners in products manufactured using wood materials. In the construction of furniture, screws are frequently used for a variety of purposes, including connecting tops to tables, cabinets, and bases, attaching shelves to end members, framing cabinets, and installing hardware [

12,

13]. The rigidity of furniture and accessories in screw joints largely depends on the screw withdrawal resistance of the screws used in the connections and the wooden materials used in production. Therefore, it is important to obtain information on the screw withdrawal resistance of wood materials in order to gain insight into the durability and stability of the whole system [

14,

15,

16].

There are a lot of studies on the screw withdrawal resistance of wood and other materials that are based on wood that can be found in the literature. Each species of tree has its own unique set of anatomical, physical, and mechanical characteristics, which set it apart from the others. Because of this, the resistance of wood and other materials based on wood to the screw withdrawal differs from species to species as well. The screw withdrawal resistance of wood depends on the wood species, wood density, temperature, wood moisture content, screw diameter, and penetration depth [

17,

18,

19,

20].

Due to global climate change, significant changes occur in the usual weather conditions. Wood and wood-based materials are exposed to variable climatic conditions at their place of use. Especially moisture and temperature changes change the physical and mechanical properties of wood and wood-based materials. The difficulties that arise in the process of preserving historical buildings are directly attributable to shifts in the climatic system, and more specifically, to the intensification of a wide range of weather phenomena. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has developed an overview of the principal issues regarding climate change and its consequences for cultural heritage. Damage caused by cycles of freezing and thawing, thermal stress, biological activity, moisture penetration, metal corrosion, crystallization, and salt dissolving are some of the things that are included on that list [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

Wood and other products based on wood can sustain damage to the tune of millions of dollars each year if they are subjected to a variety of weather conditions. Concerns have been expressed about the durability of wood and wood-based products in outdoor applications, including fungi resistance, UV resistance, moisture resistance, and dimensional stability. In the literature, it has been reported that the freeze-thaw phenomenon significantly affects the physical and mechanical properties of wood and wood-based materials. For this reason, it is very important to determine how resistant wood-based materials and other materials used with them will be to various environmental conditions. As a result, freeze-thaw durability emerges as an important factor that will determine the service life of wood and wood-based materials, especially in cold regions where the freeze-thaw phenomenon is common [

27,

28,

29,

30].

In this study, it was aimed to investigate the effect of freeze thaw cycling (FTC) process on screw direct withdrawal resistance (SDWR) of plywood produced from beech (Fagus orientalis L.), ozigo (Dacryodes buettneri) and okoume (Aucoumea klaineana Pierre) species. In addition, the effects of screwing time (before/after FTC), screw orientation (face/edge), and the number of cycles in the FTC process (from 1 to 7) on SDWR were also investigated. Changes in the structure of screws and plywood were observed after the FTC process.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, 7-layer, 12 mm thick (outer layer thickness 1 mm, inner layer thickness 2 mm) plywoods produced using beech (Fagus orientalis L.), ozigo (Dacryodes buettneri) and okoume (Aucoumea klaineana Pierre) species obtained from a plywood factory operating in Kastamonu/Turkey were used. In the production of plywood, the amount of adhesive (phenol formaldehyde) is 160 gr/m2, the press temperature is 114 °C, the press pressure is 110 bar/m2 and the pressing time is 16 minutes.

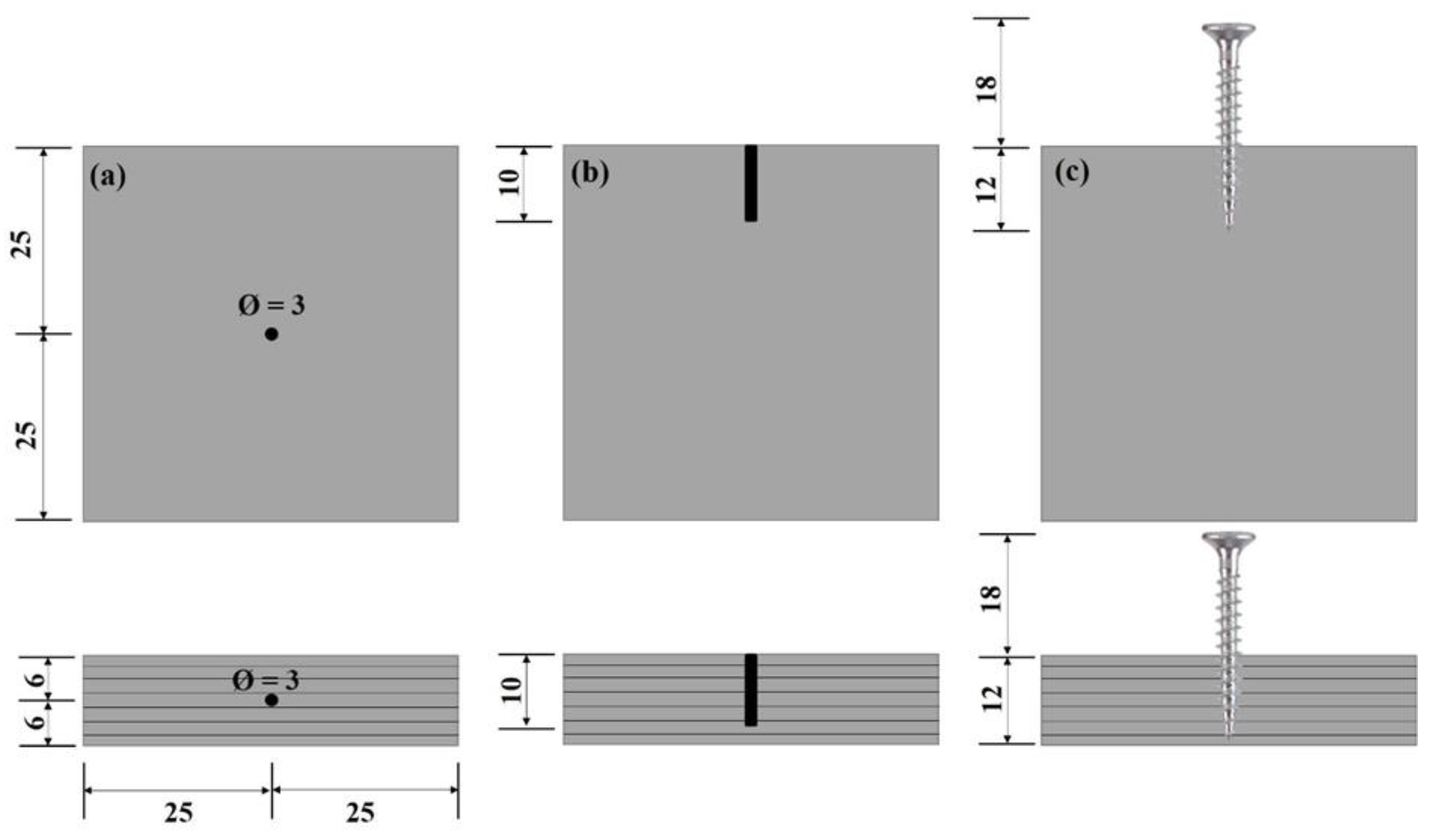

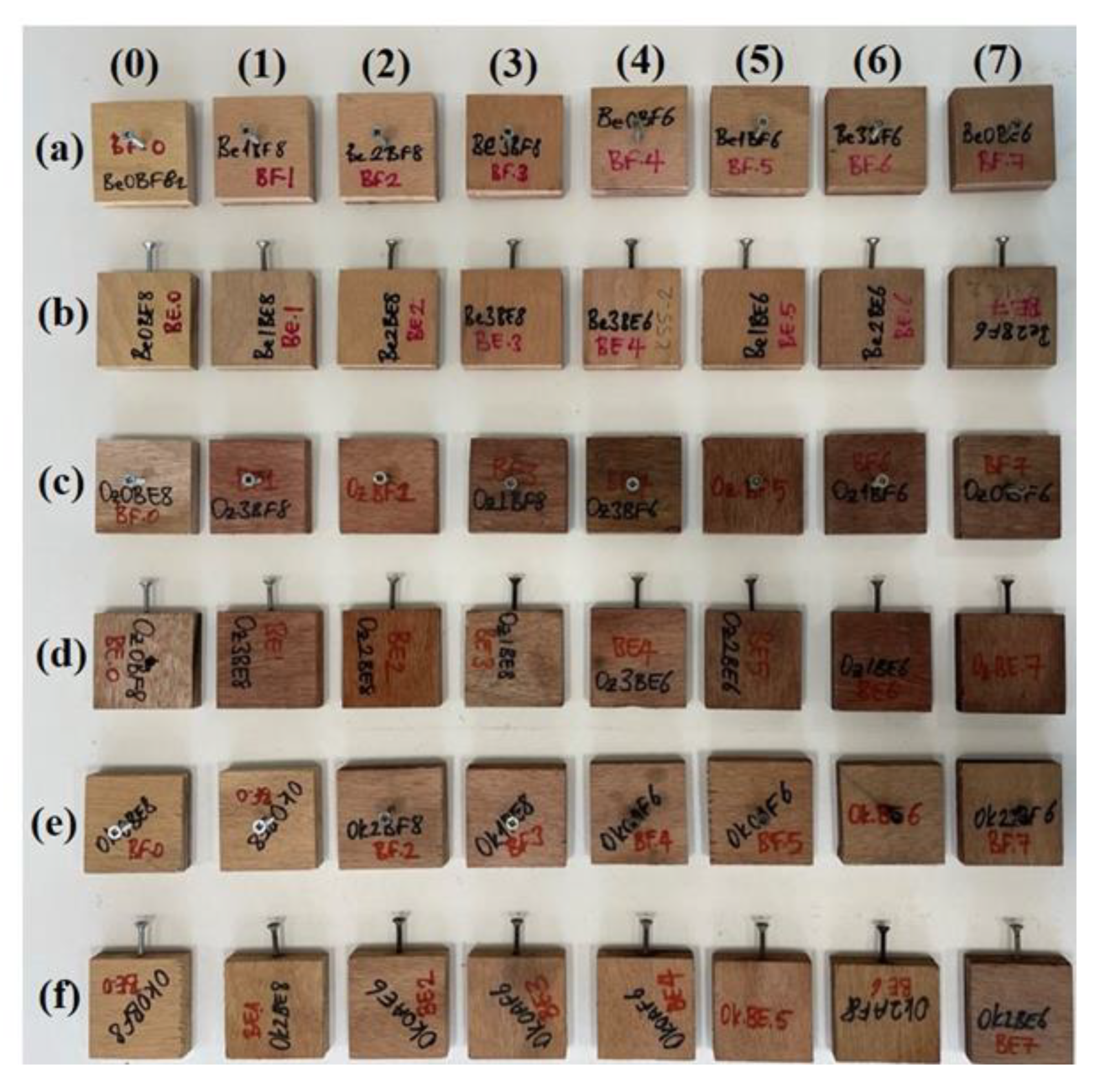

The supplied plywoods were cut in accordance with the EN 13446 standard to obtain test blocks with dimensions of 50x50x12 mm

3 (

Figure 1). The test blocks obtained were conditioned for two weeks at 65% relative humidity and 20±2 ℃. Densities of plywoods are determined according to TS EN 323 standard.

In this study, experiment parameters were determined for plywood type, screwing time (before and after cycling), screw orientation (face and edge), and the freeze-thaw cycling process. A total of 1350 test samples, 15 for each parameter, were prepared. Prepared sample codes are shown in

Table 1.

Pilot holes with a diameter of 3 mm (85.70% of the screw diameter) were drilled on the samples (

Figure 2). The drilled pilot hole depth is 10 mm and the screwing depth is 12 mm. Within the scope of the study, a full-shank single thread universal screw (grey zinc coated) with a diameter of 3.50x30 mm (shank diameter x total length) and a thread diameter of 3.90 mm was used. In order to examine the effect of the FTC process on SDWR, half of the samples were screwed before the FTC process and the other half after the FTC process. During the screwing process, care was taken to ensure that the screws made a 90° angle with the sample face or edge and that 18 mm of the screw was out of the sample. Dremel 3000 drill and workstation are used to drill pilot holes precisely. Pilot holes in the samples screwed after the FTC process were drilled after the FTC process and conditioning process.

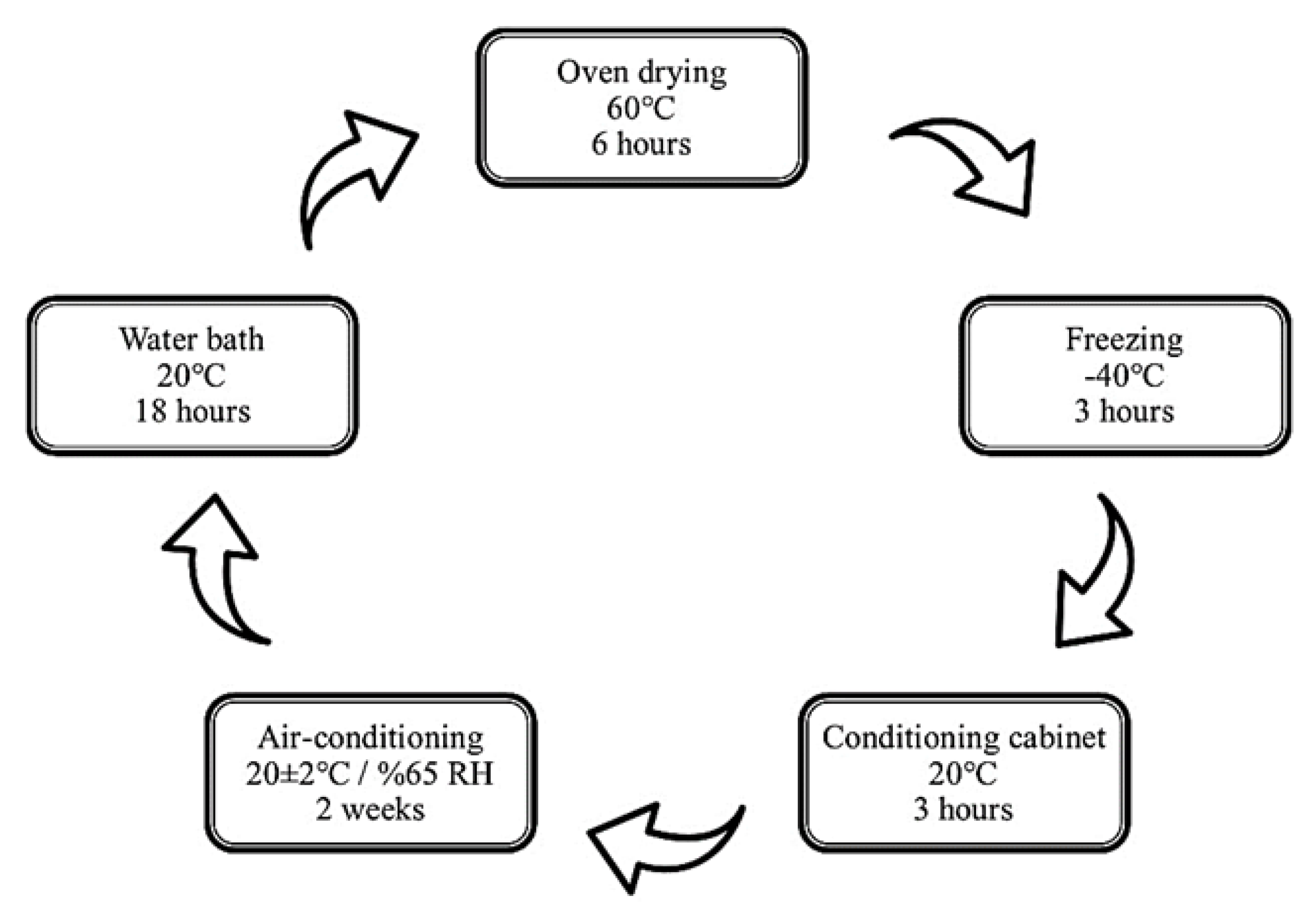

The FTC process was applied to the plywoods according to the modified EN 321 standard (

Figure 3). In this context, the samples were first kept in a laboratory-type water bath at +20 °C for 18 hours. After this process, the samples were taken out of the water bath, and the excess water was removed with the help of a napkin and kept in a laboratory type oven at +60 °C for 6 hours. At the end of the period, the samples taken from the oven were kept in a desiccator until they reached room temperature. After this process, the samples were kept in a freezer at -40 °C for 3 hours. The samples taken out of the freezer were kept in the air-conditioning cabinet at +20 °C for 3 hours and then conditioned for 2 weeks at 65% relative humidity and 20±2 °C. This process was repeated 7 times in total. The effect of each cycle stage on SDWR was examined. SDWR tests were performed on a Shimadzu AGIC/20/50KN testing machine according to the EN 13446 standard.

The IBM SPSS 26.0 application was used for the statistical evaluation of the data obtained as a result of the study. An analysis of variance was applied to determine the differences between the results. For the purpose of making a comparison of the averages, the post-hoc Duncan test was carried out with a reliability level of 95%.

3. Results and Discussion

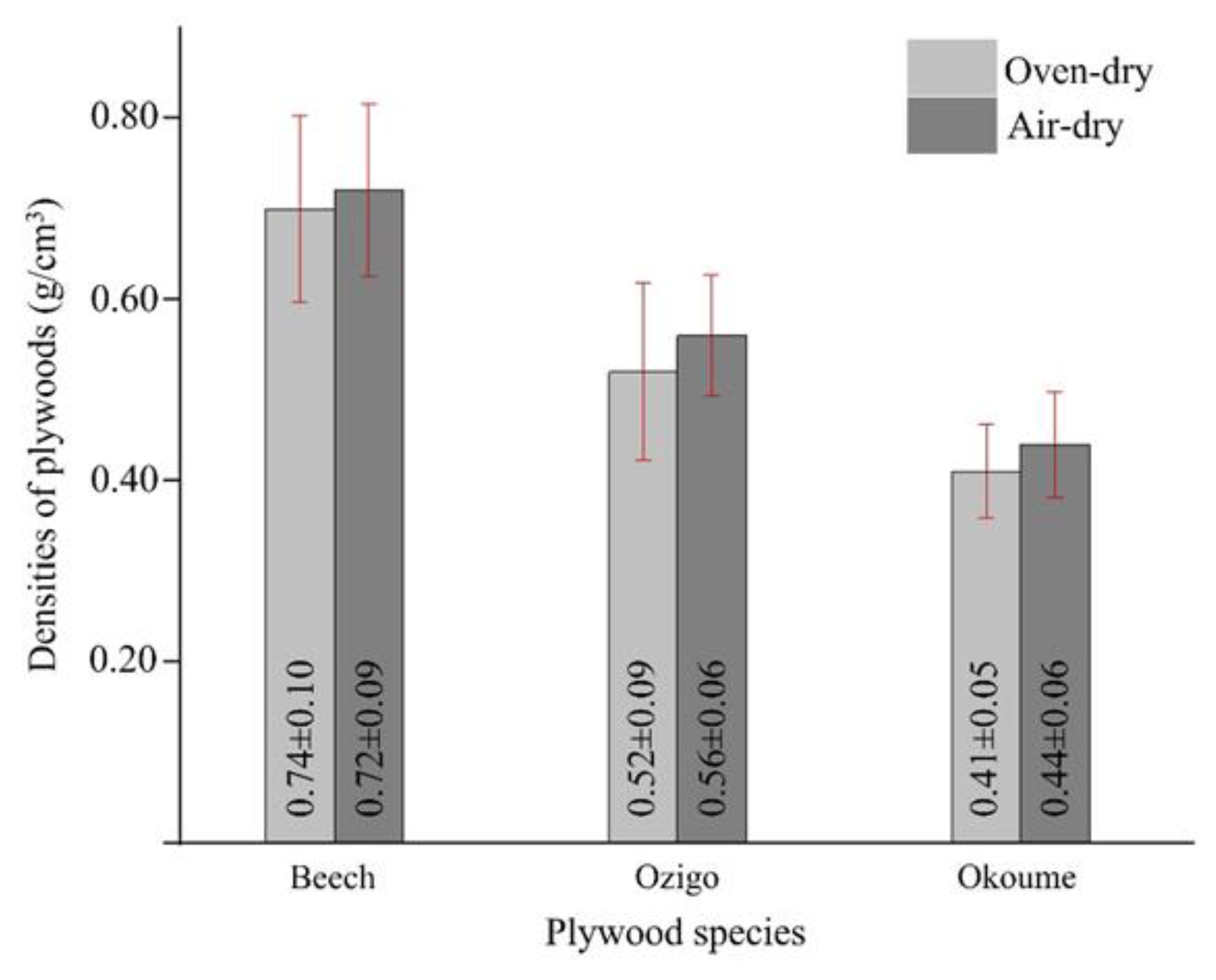

The oven-dry and air-dry densities of beech, ozigo, and okoume plywoods were determined according to TS EN 323 (

Figure 4). When the results were examined, the highest density was obtained in beech plywood, and the lowest density was obtained in okoume plywood. The oven-dry densities of beech, okoume, and ozigo solid woods are stated in the literature as 0.62 g/cm

3, 0.37 g/cm

3, and 0.53 g/cm

3, respectively. In this investigation, the densities of plywood manufactured from beech, okoume, and ozigo species were found to be higher than the densities of solid wood. This difference is assumed to be caused by the glue used in plywood manufacturing as well as condensation on the veneer sheets during pressing [

31,

32,

33,

34].

3.1. Plywood Species Effect on SDWR

Table 2 shows the mean SDWR values of beech, ozigo, and okoume plywood according to screwing time, screwing orientation, and number of cycles in FTC combinations. In general, when the SDWR values of face orientation in untreated plywoods were compared, it was determined that the highest values were obtained in beech (1279 N), ozigo (726 N), and okoume (691 N), respectively. When the SDWR values in edge orientation were compared, it was found that this order did not change and the SDWR values were 943 N, 563 N, and 487 N, respectively.

A comparison of the mean SDWR values of plywood types is given in

Table 3. When the mean SDWR values were compared, a statistically significant difference was found between the groups (p<0.05). When the mean SDWR values were compared, the highest values were obtained in beech plywood (873 N), ozigo plywood (561 N) and okoume plywood (486 N), respectively. According to this result, it was understood that the mean SDWR values were directly proportional to the density of the plywoods, in accordance with other studies in the literature [

35,

36,

37,

38].

3.2. Screwing Time Effect on SDWR

The main reason for examining the effect of screwing before and after the FTC process on SDWR is to understand how SDWR will change with the swelling and shrinkage that will occur in the screwed plywood after water treatment. On the other hand, it is known that screws made of metal will expand upon heating and contract upon freezing. It is also desirable to determine how the screwed plywoods will behave in this case with the FTC process.

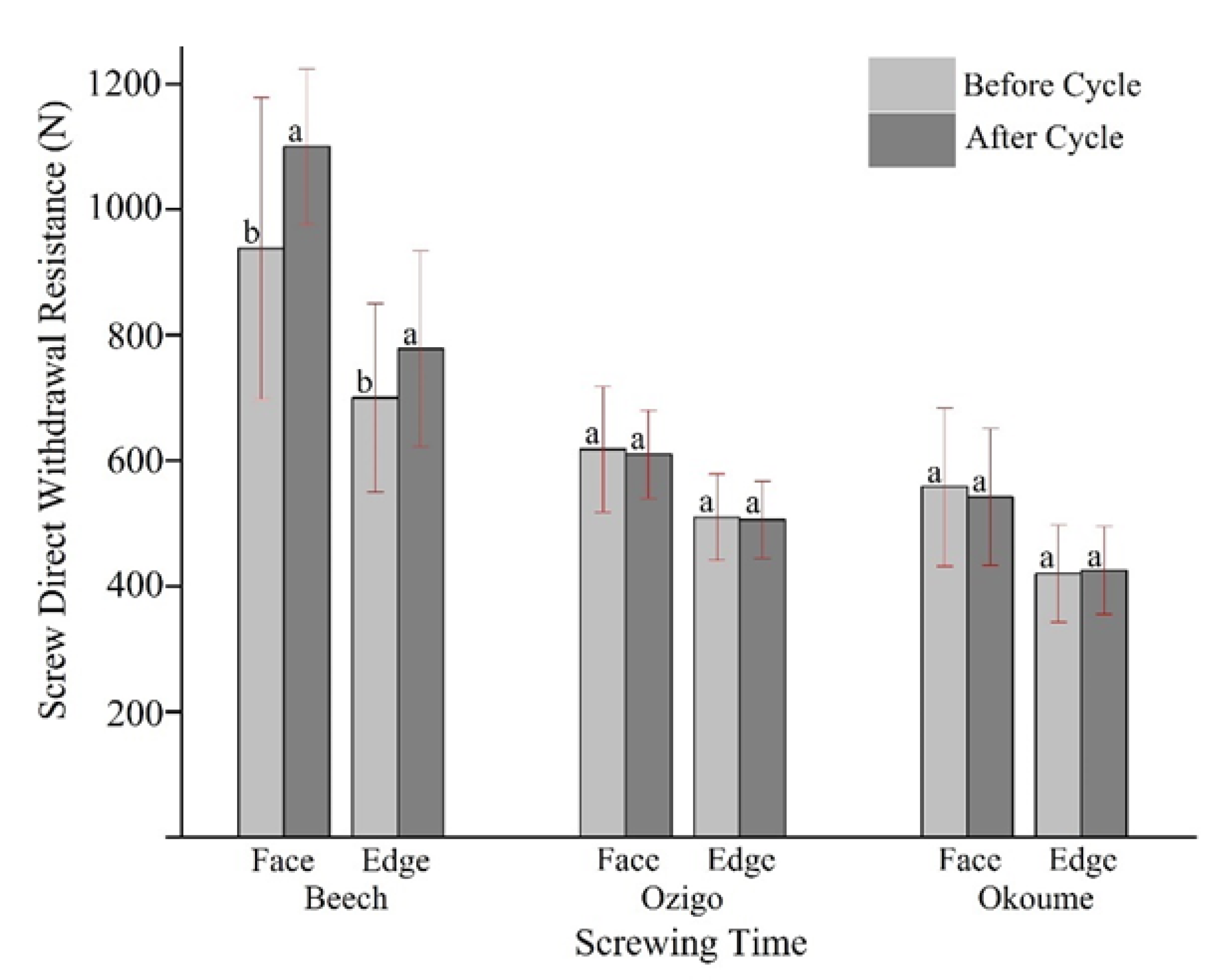

Figure 5 shows the effect of screwing time on the mean SDWR. Half of the plywoods were screwed before the FTC process and subjected to the FTC process as screwed. The other half of the plywood was subjected to conditioning after the FTC process, and after this process, pilot holes were drilled and screwed. According to

Figure 5, it is seen that the screwing time does not make a statistically significant difference in other plywoods except beech plywood (

p>0.05). Screwing after the FTC process in beech plywood gave better results than screwing before the FTC process.

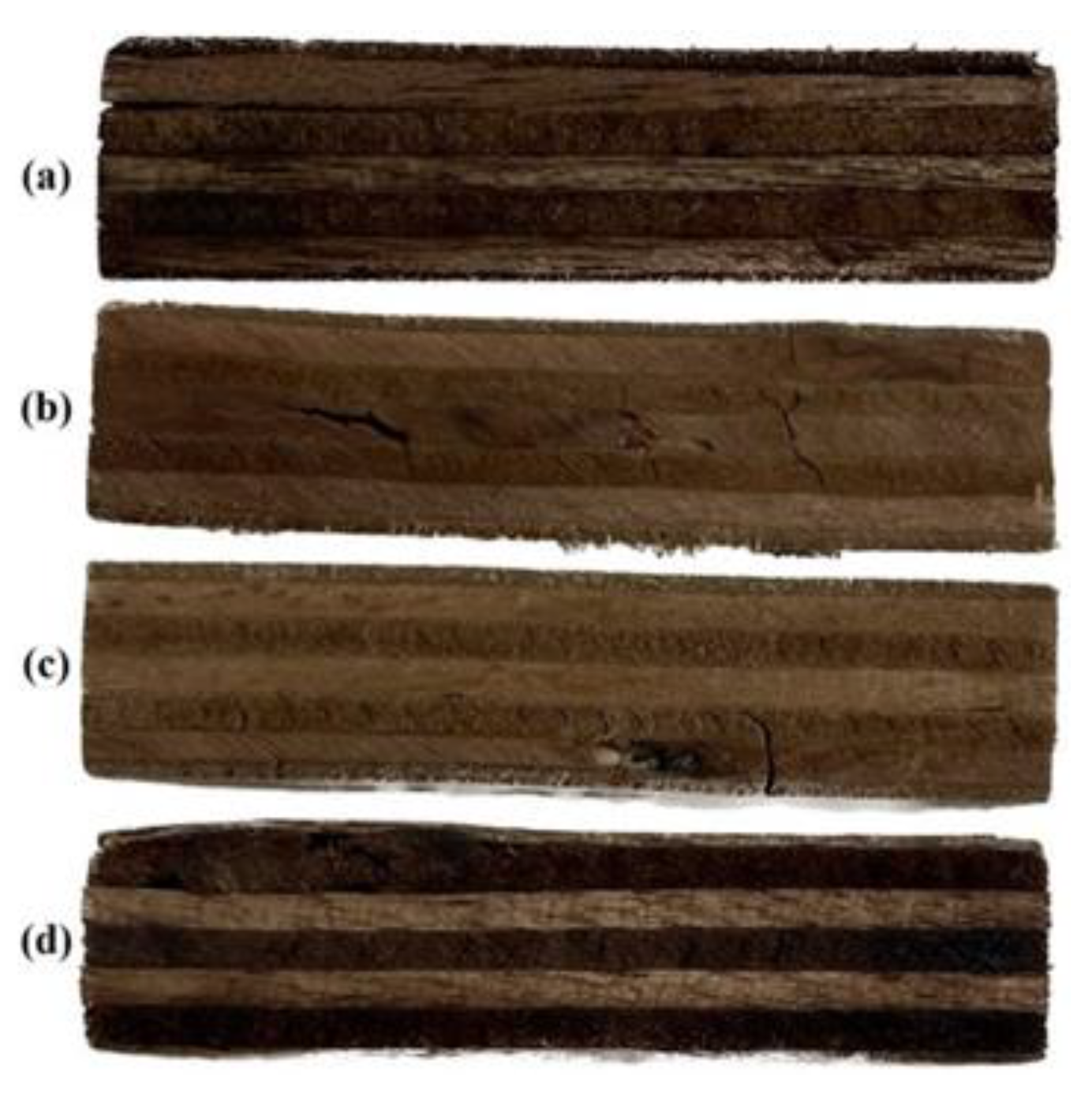

The shapes and external appearances of the plywoods under the influence of the FTC process were carefully monitored. It has been determined that the FTC process has little effect on the shape and appearance of ozigo and okoume plywoods compared to beech plywoods. At the end of the FTC process, small cracks were found on the surfaces of the beech plywoods (

Figure 6). In some samples, it was observed that there were separations in the glue line between the layers. This is thought to be due to the fact that the densities of beech plywoods are higher than that of ozigo and okoume plywoods. Since beech plywood has a high density, it is exposed to more swelling during water treatment and more shrinkage during drying than other plywoods. This causes the layers to separate from the glue line and cause cracks [

39,

40,

41].

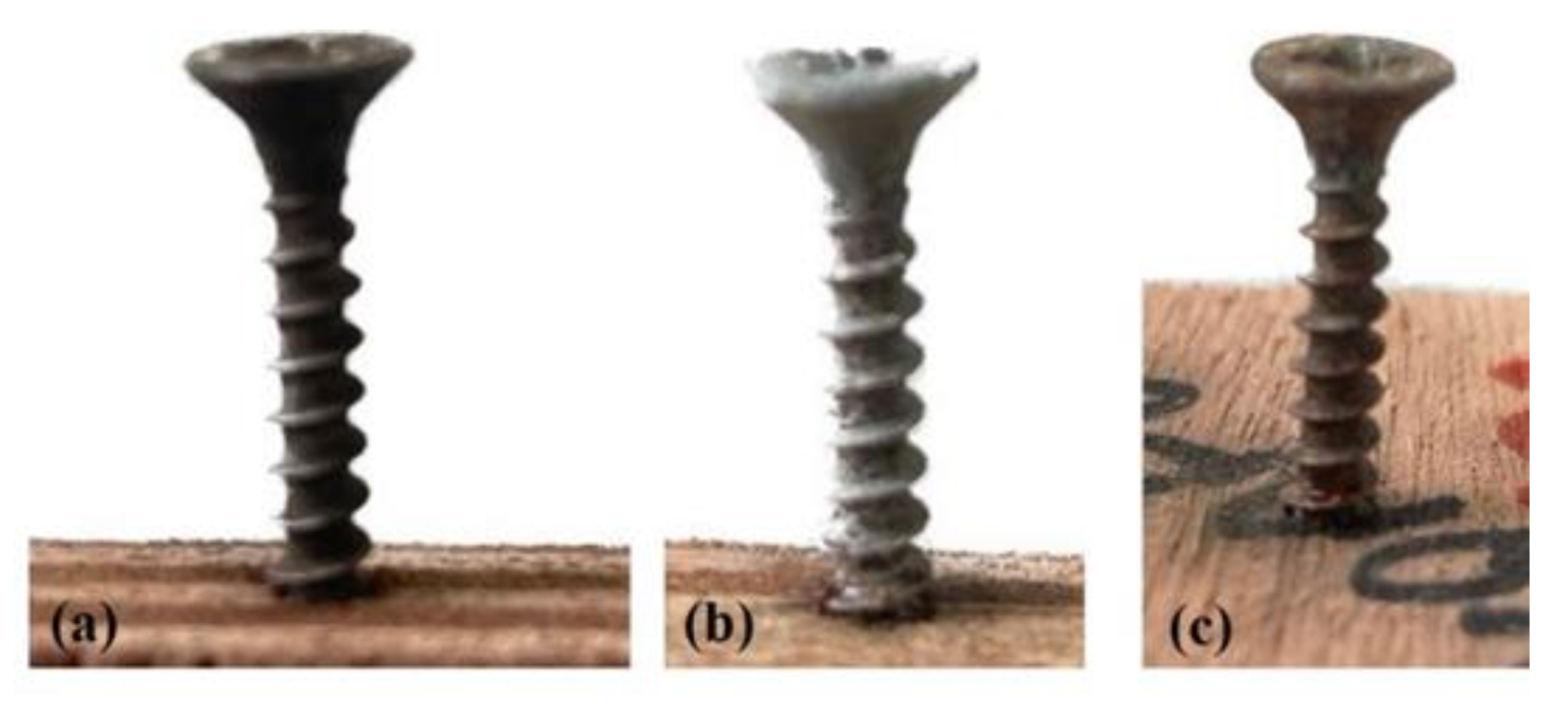

It was observed that the screws were corroded and rusted during the FTC process (

Figure 7). According to the observations made at the end of 7 cycles, no loosening, thinning, etc. findings were observed in the screws. It is thought that by increasing the number of cycles in the FTC process, the corrosion level of the screws will increase, and accordingly, SDWR will be affected.

According to all these findings, it was understood that the mean SDWR values of plywoods and the deformation in their shape and outer appearance were related to the effect of the FTC process. The main reason why the FTC process affects the mean SDWR of beech plywoods more than other plywood species may be that the density of beech plywoods is higher than other plywood species, and therefore, with higher swelling and shrinkage, it may be that the penetration of screw threads to the plywood is difficult, making the adhesion and reducing the SDWR. It is not possible to compare the results because there is no study in the literature examining the effect of the FTC process on SDWR in plywoods.

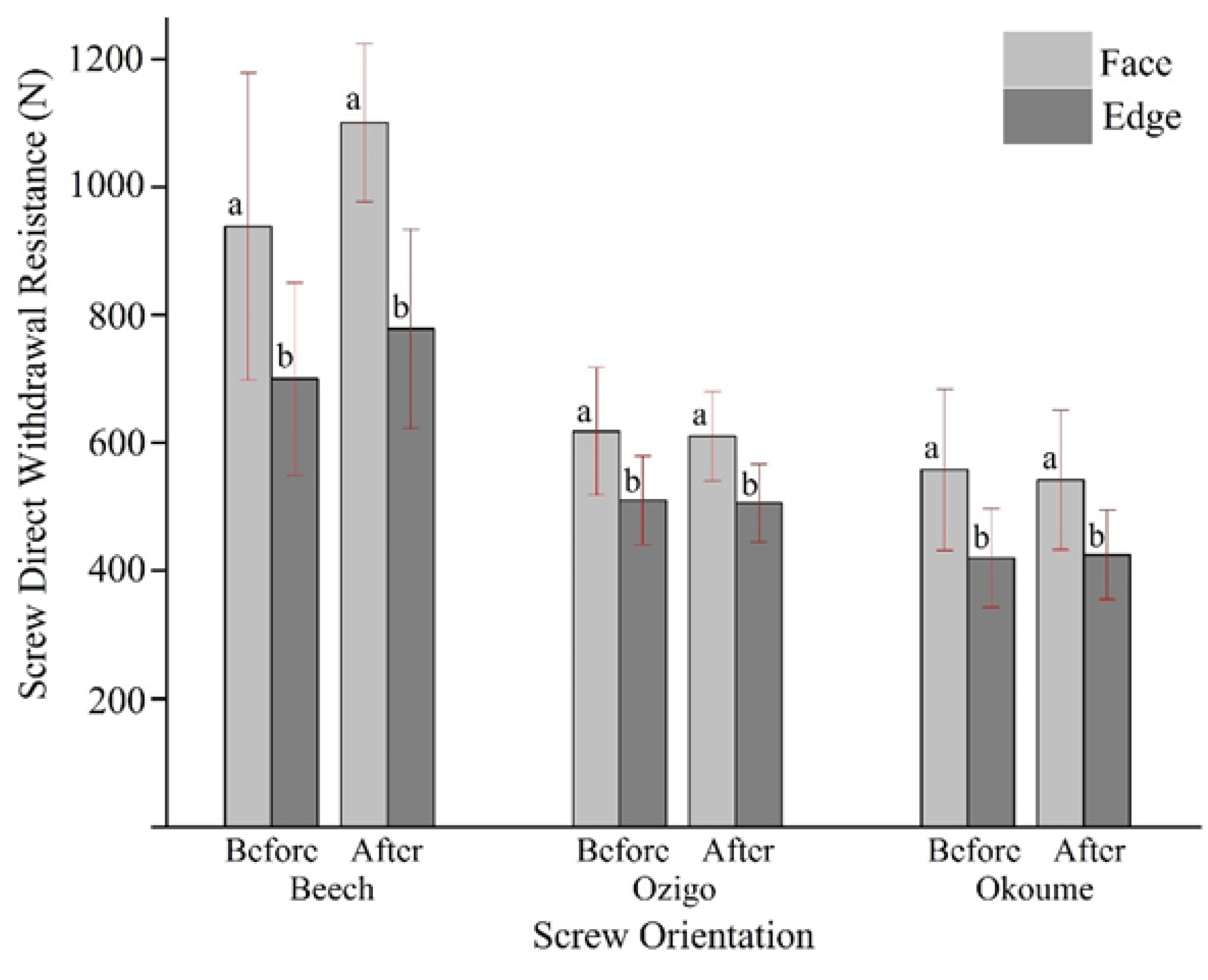

3.3. Screw Orientation Effect on SDWR

The SDWR test results performed on the face and edge directions of beech, ozigo, and okoume plywood are given in

Figure 8. A statistically significant difference was found between the mean SDWR values in all plywood species in face and edge orientation (p<0.05). It was determined that the mean SDWR values of plywood screwed in face orientation were higher in all plywood species than those screwed in edge orientation. It has been determined that the mean SDWR values of the plywoods screwed after the FTC process are generally higher than the screwed plywoods before the FTC process.

In general, it is known that with the increase in the density of wood and wood-based composites, their mechanical properties and SDWR values also increase. On the other hand, due to the pressing process of plywood during production, an increase in density occurs in the thickness direction. Therefore, the density in the face orientation is higher than in the edge orientation [

42,

43,

44]. The main reason for the higher SDWR in the face orientation than in the edge orientation is thought to be the difference in density. Also, during screwing from the face orientation, the screw penetrates each of the plywood layers. Screw treads can hold on to each layer. This does not apply to screwdriving from the edge orientation. When screwing from the edge, the screw treads can only hold on to a few of the plywood layers. Another reason for the SDWR differences in face and edge orientation is thought to be due to this situation.

3.4. Freeze Thaw Cycle Effect on SDWR

The SDWR test results of beech, ozigo, and okoume plywoods according to the effect of the FTC process are given in

Table 4. Accordingly, it was determined that there was a statistically significant difference between the mean SDWR values in all plywood species (

p<0.05).

When

Table 4 is examined, it is determined that the mean SDWR values of all plywood species decreased with the increase in the number of cycles in the FTC process. On the other hand, for all plywood species, it was observed that the mean SDWR values of screwed plywoods before the FTC process decreased more than those of screwed plywoods after the FTC process. According to this result, it can be said that there is a relationship between the FTC process and the screwing time.

When the relationship between the screwing of plywood from face and edge orientations and the number of cycles in the FTC process is examined, it is understood that the increase in the number of cycles has the most effect on screwing from the edge orientation. For example, when the samples screwed after the FTC process in beech plywood were examined, the mean SDWR values of the samples screwed from the face orientation decreased by 27.83% after the 7th cycle compared to the control groups, while the mean SDWR values of the samples screwed from the edge orientation decreased by 38.28%. This is thought to be due to the fact that the shrinkage and swelling ratio in the edge orientation, which occurs with moisture in plywoods, is higher than the shrinkage and swelling ratio in the face orientation, and accordingly, the bonding strength between the layers is reduced [

39,

45,

46,

47,

48].

It has been observed that the FTC process not only has an effect on SDWR in plywood, but also affects the appearance properties. In

Figure 9, it can be seen how the external appearance of beech, ozigo, and okoume plywood is affected after a total of 7 cycles with the control samples. The color of all plywoods, especially ozigo plywoods, darkened with the increase in the number of cycles.

4. Conclusions

This study basically presents the relationship between the FTC process and SDWR, but in real use, plywood is exposed to such extreme temperatures or more freezing effects periodically and for longer periods of time. It should be known that the increase or decrease in the number of cycles, temperature and exposure time in the FTC process may have an effect on SDWR. In addition, prolonged exposure to natural climatic temperature variation is required to better correlate data obtained under laboratory conditions with natural exposure results.

According to the results of the study, the oven dry densities of beech, ozigo, and okoume plywoods were determined as 0.74 gr/cm3, 0.52 gr/cm3, and 0.41 gr/cm3, respectively.

When the effect of plywood species on SDWR was examined, the mean SDWR values of beech, ozigo, and okoume plywoods were found to be 873 N, 561 N and 486 N, respectively, in direct proportion to the density.

When the mean SDWR values of the plywoods exposed to the FTC process were compared with the mean SDWR values of the plywoods that were not exposed to the FTC process, it was determined that there was no statistically significant difference except for the beech plywoods. When the mean SDWR values of beech plywoods are examined, better results are obtained in screwed plywoods after the FTC process compared to screwed plywoods before the FTC process. It is thought that this situation is caused by microcracks in beech plywoods due to the FTC process.

When the effect of screw orientation on mean SDWR was examined, it was determined that the test results obtained from face orientation were higher than those obtained from edge orientation in all plywood species.

When the effect of the FTC process on the mean SDWR was examined, it was determined that the mean SDWR decreased in all plywood species with the increase in the number of cycles in the FTC process. With the effect of the FTC process, mean SDWR decreased more in edge orientation than in face orientation. This shows that the FTC process affects edge orientation more than face orientation.

It has been determined that the color of the plywood under the influence of the FTC process generally becomes darker with the increase in the number of cycles in the FTC process. In addition, with the increase in the number of cycles in the FTC process, it has been observed that corrosion occurs in the screws.

It is recommended to carry out new studies by modifying the FTC process conditions and the cycle number and using different fasteners in order to support this study, which was carried out in order to understand how the resistance properties of the connection points are affected, especially in harsh outdoor weather conditions for plywood used in the construction and furniture industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B. and A.K.; methodology, E.B.; software, A.K.; validation, E.B. and A.K.; formal analysis, E.B.; investigation, E.B.; resources, E.B. and A.K.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B.; writing—review and editing, E.B.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, E.B.; project administration, E.B.; funding acquisition, E.B. and A.K.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kromoser, B.; Braun, M.; Ortner, M. Construction of All-Wood Trusses with Plywood Nodes and Wooden Pegs: A Strategy towards Resource-Efficient Timber Construction. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 2568. [CrossRef]

- Möller, E. Tendenzen Im Holzbau. Bautechnik 2013, 90, 42–46. [CrossRef]

- Jorda, J.; Kain, G.; Barbu, M.-C.; Petutschnigg, A.; Král, P. Influence of Adhesive Systems on the Mechanical and Physical Properties of Flax Fiber Reinforced Beech Plywood. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 3086. [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yang, L.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, J.; Syed-Hassan, S.S.A.; Sun, H.; Hu, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S. Conversion and Transformation of N Species during Pyrolysis of Wood-Based Panels: A Review. Environmental Pollution 2021, 270, 116120. [CrossRef]

- Kalami, S.; Arefmanesh, M.; Master, E.; Nejad, M. Replacing 100% of Phenol in Phenolic Adhesive Formulations with Lignin. J Appl Polym Sci 2017, 134, 45124. [CrossRef]

- Bekhta, P.; Sedliačik, J. Environmentally-Friendly High-Density Polyethylene-Bonded Plywood Panels. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11, 1166. [CrossRef]

- Karthäuser, J.; Biziks, V.; Mai, C.; Militz, H. Lignin and Lignin-Derived Compounds for Wood Applications—a Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 2533. [CrossRef]

- Karri, R.; Lappalainen, R.; Tomppo, L.; Yadav, R. Bond Quality of Poplar Plywood Reinforced with Hemp Fibers and Lignin-Phenolic Adhesives. Composites Part C: Open Access 2022, 9, 100299. [CrossRef]

- Kasal, A. Effect of the Number of Screws and Screw Size on Moment Capacity of Furniture Corner Joints in Case Construction. For Prod J 2008, 58.

- Krzyżaniak, Ł.; Kuşkun, T.; Kasal, A.; Smardzewski, J. Analysis of the Internal Mounting Forces and Strength of Newly Designed Fastener to Joints Wood and Wood-Based Panels. Materials 2021, 14, 7119. [CrossRef]

- Krzyżaniak, Ł.; Smardzewski, J. Impact Damage Response of L-Type Corner Joints Connected with New Innovative Furniture Fasteners in Wood-Based Composites Panels. Compos Struct 2021, 255, 113008. [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Haviarova, E. Lower Tolerance Limits for Screw Withdrawal in Wood. Wood and Fiber Science 2019, 51, 375–386. [CrossRef]

- Yorur, H.; Birinci, E.; Gunay, M.N.; Tor, O. Effects of Factors on Direct Screw Withdrawal Resistance in Medium Density Fiberboard and Particleboard. Maderas. Ciencia y tecnología 2020, 0–0. [CrossRef]

- Örs, Y.; Özen, R.; Doğanay, S. Screw Holding Ability (Strength) of Wood Materials Used in Furniture Manufacture. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry 1998, 22, 29–34.

- Kilic, M.; Celebi, G. Compression, Cleavage, and Shear Resistance of Composite Construction Materials Produced from Softwoods and Hardwoods. J Appl Polym Sci 2006, 102, 3673–3678. [CrossRef]

- Çağatay, K.; Efe, H.; Burdurlu, E.; Kesik, H.İ. Determination of Screw Holding Strength of Some Wood Materials. Kastamonu University Journal of Forestry Faculty 2012, 12, 321–328.

- Aytekin, A. Determination of Screw and Nail Withdrawal Resistance of Some Important Wood Species. Int J Mol Sci 2008, 9, 626–637. [CrossRef]

- Yorur, H.; Birinci, E.; Gunay, M.N.; Tor, O. Effects of Factors on Direct Screw Withdrawal Resistance in Medium Density Fiberboard and Particleboard. Maderas. Ciencia y tecnología 2020, 22, 0–0. [CrossRef]

- Rammer, D.R. Fastenings, Wood Handbook, Wood as Engineering Material. General Technical Report; 2010;

- Gašparík, M.; Karami, E.; Sethy, A.K.; Das, S.; Kytka, T.; Paukner, F.; Gaff, M. Effect of Freezing and Heating on the Screw Withdrawal Capacity of Norway Spruce and European Larch Wood. Constr Build Mater 2021, 303, 124457. [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, C.B.; Hernández, R.E. Balsam Fir Strength Behavior at Moisture Content in Service after Freezing in Green Condition. Bioresources 2018, 14, 401–408. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, J. Effect of Low Temperature Cyclic Treatments on Modulus of Elasticity of Birch Wood. Bioresources 2015, 10. [CrossRef]

- Gerhards, C.C. Effect of Moisture Content and Temperature on the Mechanical Properties of Wood: An Analysis of Immediate Effects. Wood and Fiber Science 1982, 14, 4–36.

- Hao, L.; Herrera-Avellanosa, D.; Del Pero, C.; Troi, A. What Are the Implications of Climate Change for Retrofitted Historic Buildings? A Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7557. [CrossRef]

- Phillipson, M.C.; Emmanuel, R.; Baker, P.H. The Durability of Building Materials under a Changing Climate. WIREs Climate Change 2016, 7, 590–599. [CrossRef]

- Vandemeulebroucke, I.; Caluwaerts, S.; Van Den Bossche, N. Factorial Study on the Impact of Climate Change on Freeze-Thaw Damage, Mould Growth and Wood Decay in Solid Masonry Walls in Brussels. Buildings 2021, 11, 134. [CrossRef]

- Pilarski, J.M.; Matuana, L.M. Durability of Wood Flour-Plastic Composites Exposed to Accelerated Freeze-Thaw Cycling. Part I. Rigid PVC Matrix. Journal of Vinyl and Additive Technology 2005, 11, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Pilarski, J.M.; Matuana, L.M. Durability of Wood Flour-Plastic Composites Exposed to Accelerated Freeze–Thaw Cycling. II. High Density Polyethylene Matrix. J Appl Polym Sci 2006, 100, 35–39. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sain, M.; Cooper, P.A. Hygrothermal Weathering of Rice Hull/HDPE Composites under Extreme Climatic Conditions. Polym Degrad Stab 2005, 90, 540–545. [CrossRef]

- Szmutku, M.B.; Campean, M.; Porojan, M. Strength Reduction of Spruce Wood through Slow Freezing. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products 2013, 71, 205–210. [CrossRef]

- Salca, E.-A.; Bekhta, P.; Seblii, Y. The Effect of Veneer Densification Temperature and Wood Species on the Plywood Properties Made from Alternate Layers of Densified and Don-Densified Veneers. Forests 2020, 11, 700. [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, A.; Borysiuk, P.; Mamiński, M.; Zbieć, M. Veneer Densification as a Tool for Shortening of Plywood Pressing Time. Drvna Industrija 2010, 61, 193–196.

- Jakob, M.; Stemmer, G.; Czabany, I.; Müller, U.; Gindl-Altmutter, W. Preparation of High Strength Plywood from Partially Delignified Densified Wood. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1796. [CrossRef]

- Bal, B.; Bektaş, İ. Determination of Relationship between Density and Some Physical Properties in Beech and Poplar Wood. Mobilya ve Ahşap Malzeme Araştırmaları Dergisi 2018, 1, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Dungani, R.; Karliati, T.; Hadiyane, A.; Suheri, A.; Suhaya, Y. Coconut Fibres and Laminates with Jabon Trunk (Anthocephalus Cadamba Miq.) Veneer for Hybrid Plywood Composites: Dimensional Stability and Mechanical Properties. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products 2019, 77, 749–759. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.A.; Salenikovich, A.; Mohammad, M. Localized Density Effects on Fastener Holding Capacities in Wood-Based Panels. For Prod J 2007, 57, 103–109.

- Khandkar-Siddikur, R.; Nazmul Alam, D.M.; Nazrul Islam, M.D. Some Physical and Mechanical Properties of Bamboo Mat-Wood Veneer Plywood. ISCA Journal of Biological Sciences 2012, 1, 61–64.

- Abdul Khalil, H.P.S.; Nurul Fazita, M.R.; Bhat, A.H.; Jawaid, M.; Nik Fuad, N.A. Development and Material Properties of New Hybrid Plywood from Oil Palm Biomass. Mater Des 2010, 31, 417–424. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Suzuki, S. Evaluating the Durability of Wood-Based Panels Using Internal Bond Strength Results from Accelerated Aging Treatments. Journal of Wood Science 2011, 57, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, M.; Chen, C.; Cao, G.; Mao, A.; Wan, H. Adhesives from Polymeric Methylene Diphenyl Diisocyanate Resin and Recycled Polyols for Plywood. For Prod J 2017, 67, 275–282. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Delgado, N.; Fuentes, J.; Fuentealba, C.; Vega-Lara, J.; García, D.E. Exterior Grade Plywood Adhesives Based on Pine Bark Polyphenols and Hexamine. Ind Crops Prod 2018, 122, 340–348. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q. Screw-Holding Capacity of Two Furniture-Grade Plywoods. Forest Products Journal 1999, 49, 56–59.

- Verma, C.S.; Chariar, V.M. Development of Layered Laminate Bamboo Composite and Their Mechanical Properties. Compos B Eng 2012, 43, 1063–1069. [CrossRef]

- Celebi, G.; Kilic, M. Nail and Screw Withdrawal Strength of Laminated Veneer Lumber Made up Hardwood and Softwood Layers. Constr Build Mater 2007, 21, 894–900. [CrossRef]

- Taghiyari, H.R.; Hosseini, S.B.; Ghahri, S.; Ghofrani, M.; Papadopoulos, A.N. Formaldehyde Emission in Micron-Sized Wollastonite-Treated Plywood Bonded with Soy Flour and Urea-Formaldehyde Resin. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 6709. [CrossRef]

- Sugahara, E.; Casagrande, B.; Arroyo, F.; De Araujo, V.; Santos, H.; Faustino, E.; Christoforo, A.; Campos, C. Comparative Study of Plywood Boards Produced with Castor Oil-Based Polyurethane and Phenol-Formaldehyde Using Pinus Taeda L. Veneers Treated with Chromated Copper Arsenate. Forests 2022, 13, 1144. [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Sato, M. Evaluation of the Self-Bonding Ability of Sugi and Application of Sugi Powder as a Binder for Plywood. Journal of Wood Science 2010, 56, 194–200. [CrossRef]

- Jakob, M.; Stemmer, G.; Czabany, I.; Müller, U.; Gindl-Altmutter, W. Preparation of High Strength Plywood from Partially Delignified Densified Wood. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1796. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).