1. Introduction

How COSs are designed have major impacts on how students use the space, and this in turn can affect the wellbeing, sense of belonging and learning success of students, namely their ‘student experience’. Many studies argue that the physical environment of a campus affects a university’s image and reputation (Eckert, 2012; Klassen, 2001; Palacio, Meneses, & Pérez, 2002; Suttell, 2007), as well as their students’ satisfaction and success (Mai, 2005; Pascarella, Ethington, & Smart, 1988; Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005; Strange & Banning, 2015). Numerous studies have shown the social, environmental, economic, and health benefits of COS (S. S. Lau & Yang, 2009; S. S. Y. Lau, Gou, & Liu, 2014; McFarland, Waliczek, & Zajicek, 2008; Woolley, 2003) which include: strengthening communities; sustaining the performance of students (encouraging social cohesion and inclusion, academic identity and cultural opportunities, and enhancing quality of life); providing more attractive places to study, play and live; improving the environment (air quality, foot print, biodiversity, energy saving); improving public health as well as its general mood and attitude (wellbeing and stress reduction); promoting better mental health (environmental awareness); functioning as a marketing tool for the institution; hosting universal events; supporting local communities and their economies, and attracting investment.

Consequently, finding the nexus between the use and experience of COSs, and their physical characteristics represents a step towards understanding their relevance to the student experience. An integrative relationship is also needed between campus buildings and open spaces for campuses to function in an efficient, comfortable, and sustainable manner. The role of a COS is crucial as it impacts student health, wellness, productivity, and overall satisfaction (Eckert, 2012; Zimring, 1982). Universities in the UK spend £4 billion annually on maintaining campuses which accounts for 11.7% of the UK’s total spend on the university sector (UK, 2018). Other references show that 38% is spent on campus developments and operating costs, and as COS represents 40 to 85% of the total campus area, it represents an area of significant investment (Desrochers & Wellman, 2011; Thanassoulis, Kortelainen, Johnes, & Johnes, 2011).

However, very little research demonstrates the links between the impacts of investments in campus planning - particularly for outdoor spaces - and the student experience. Campus planners and university estate departments need to optimise investments and verify the specific spaces and particular spatial improvements that would yield the best student experience, i.e. ensure that COS design developments achieve the best value for money. The aim of this paper is, therefore, to examine and determine the relationship between space design and user experience by considering the current status of the university (type, area and ranking features) and its level of investment (costs and impact) in its COSs. This aim is approached via a three-phase integrative framework and results in a validated assessment model - COS Experience Calculator – that quantifies the most used/vital, best used/engaging, and most valued/beneficial COS. The paper compares COSs in significant universities in the UK and USA with a of mix environments combining natural and high-quality/advanced features (e.g. well-maintained footpaths, comfortable seats, commercial facilities, and water landscapes) and their relationship with the students’ experiences. These factors comprise an essential part of any successful investment strategy.

This article draws on peer-reviewed publications to review the factors that contribute to campus design from different perspectives. A total of 501 references and databases, dating from 1968 to 2019, have been reviewed including: 89 books or book chapters, 297 journal papers, 20 doctoral theses, and 95 articles/reports/newsletters. This wide-ranging literature guided the analysis of the features which correspond to links between the campus design and user experience within campus - viewed here from three broad perspectives. These perspectives are:

Ph#1 - Student experience: Behavioural, mental, social and cultural aspects;

Ph#2 - Design perspective: Physical landscaping features and urban values;

Ph#3 - Investment perspective: Cost, value, repetition and/or benefits.

2. Literature Review - COS and the Outdoor Experience

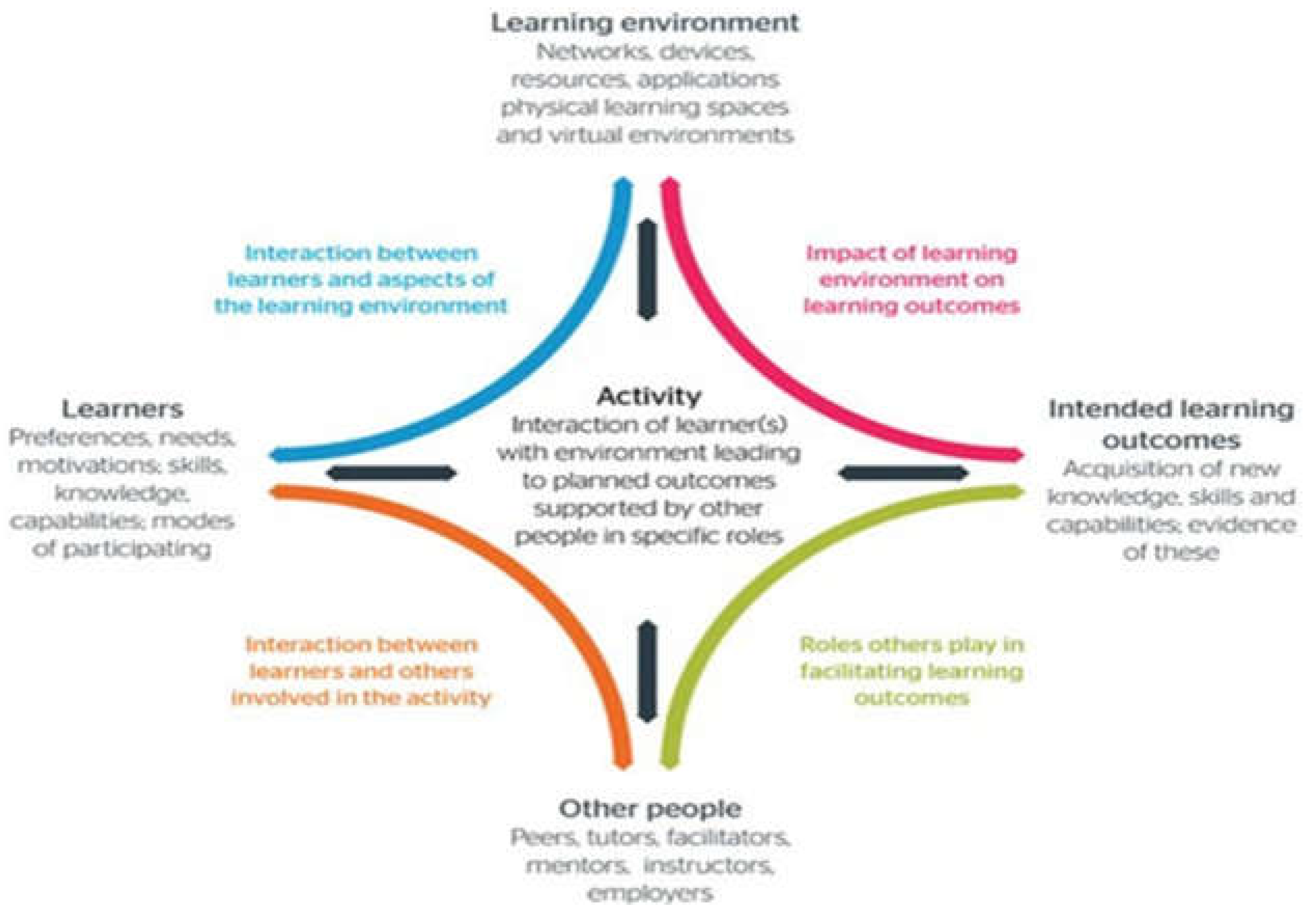

Several decades of research support the view that it is the activity that the learner engages in and the outcomes of that activity that are most significant for learning (Lippman, 2002). Design for learning should therefore focus primarily on the activities undertaken by learners, and then secondarily consider the facilities or materials that support them. Among the theories that emphasize the central importance of activity on the part of the learner or student is Beetham’s (2007) ‘learning activity design’ (illustrated in

Figure 1).

The first part of literature concerns the student experience generally gained from or enhanced within the university campus, and particularly the outdoor environment. Indeed, a big part of the university experience is determined by the social life a student leads which tends to mean joining the extracurricular activities and societies that comprise part of a university’s social provision. Although significant focus is placed on the academic ranking of universities, increasingly students are judging institutions by the overall university experience they offer. Within this study, several references were reviewed by key authors, such as Carney Strange, James Banning, Alexander Astin, George Kuh, Vincent Tinto (retention theory and interactions theory), and data was analysed from the systems and rankings of universities which addressed their range and quality of activities. The study focused on answering questions such as: What activities are most practiced on campus; which activities (positively or negatively) contribute to or impact the university and students’ education; when and how are these impacts experienced; what experiences are gained, and which should universities focus on improving (or maybe permitting)?

Multiple definitions of the terms ‘campus open space’ and ‘student experience’ are applied in the literature. This study adopts a narrower focus to the definition by incorporating all areas outside buildings, but inside the university campus. These are open for student and public use, and offer spaces to learn, relax, play, and interact with other experiences. This focus allows for the recognition of places and conditions for sports, recreation, relaxation, observation, meeting, and social activities. The quality of the spatial experience is not only accessed through its visual appearance, but also its ability to meet user needs and support the functional, convenient, safe, pleasant and exhilarating experiences of campus users (Hanan, 2013).

Maslow’s pyramid of human needs (McLeod, 2007) includes: (1) Physiological (food, warmth & survival); (2) safety and security; (3) affiliation (belonging & acceptance); (4) esteem (by feeling valued by others through a person’s status), and (5) self-actualization (through artistic expression and fulfilment). Designers and planners are expected to cater for these ‘human factor’ needs by creating responsive urban spaces where the human interacts with elements of the spatial environmental which are linked to their behaviour and their natural, psychological & sociological composition. Facilitating these activities through the physical outdoor environment in a way that encourages the best possible creative performance of students represents a challenge for both instructors and academics, as well as campus architects or planners.

Indeed, it has been proven that the use and popularity of a space depends greatly on the location and the details of its design (Marcus & Francis, 1997). Having reviewed literature on existing campus spaces, several authors have concluded that the quality of a COS represents values that directly and indirectly affect the interaction between students and the campus spaces, by embodying the quality of urban or university life (Chapman, 2006; Kenney, Dumont, & Kenney, 2005; Strange & Banning, 2001).

As such, this article considers the diverse typologies of COS as classified from a broad range of literature (CABE, 2000). One classification involves the ‘four components’ a student experiences in terms of the student journey (Temple, Callender, Grove, & Kersh, 2016): Application experience (interactions between potential students and campus); academic experience (interactions with the campus associated with students studies); campus experience (student life within campus), and the graduate experience (role in assisting a student’s transition to employment or further study).

Drawing on Bloom (1956), another classification outlines three basic dimensions to a student experience: Behavioural experiences (such as attendance and involvement); emotional experiences (such as interest, enjoyment, or a sense of belonging), and cognitive experiences (going beyond the learning requirements, and relishing challenge). Out-of-class activities that impact the development of cognitive skills may also promote the development of abilities in ethical and moral reasoning (Kuh, 1995). Each of these dimensions have a ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ quality, which represents a form of experience (added value) and is separated from inexperience (counterproductive behaviour or lack of involvement, withdrawal, or apathy).

In terms of the benefits, the value of actively involving students in the university grounds is generally described from one of four perspectives: Functional (how does it benefit the university?); developmental (how does it benefit the student?); social (how does it benefit society?), and ecological (the integration of all benefits to the environment). This classification is supported by several studies with minor differences. For example, Conyne and Clack (1981) stated that the campus environment includes the physical component, a social component, an institutional component and an ‘ecological-climate dimension’ derived from the interaction of the aforementioned three.

The ‘Campus Master Plan’ is a road map to the future of the physical campus; it incorporates the facilities, systems and activities needed to achieve the University’s core mission and enrolment goals (e.g. the quality of on campus a student’s experience). As such, the study reviews the development of different settings of open spaces like campus gateways, transitional spaces, outdoor learning commons, social hubs or cubicles, and other places where different learning scenarios occur that are influenced by physical space design features (Calvo-Sotelo, 2012, 2014; Coulson, Roberts, & Taylor, 2017; Dober, 2000; Francis, 2003). These represent the links between the typologies of COS design and the typologies of use (classifications of associated student needs and use). For example, varied opportunities for involvement and motivating factors stimulate students to form relationships within the external space and contribute to the quality of student life as well as create a connection to the campus. Several studies suggested that ‘group discussion’ in particular has made a significant contribution to student experiences on COS, and that such bonds lead to a strong campus community (Kuh, 1995). Planners in response look for the physical features that allow for and support such activities. As such, higher education institutions assess the performance of their students and facilities at different stages by applying different methods and using different factors/criteria (e.g. assessing formal and informal activities).

3. Research Methodology

This paper employed a multiple-method case study strategy involving three phases of data collection and analysis:

- (1)

Ph#1 - Explore & describe (University profile);

- (2)

Ph#2 - Observe & examine (Observation data sheets and COS Design Index);

- (3)

Ph#3 - Balance & validate (COS Exp score).

The three stages conclude with recommendations for three key sectors (academia, planning and investment) to achieve the best value for cost. These recommendations were developed and then validated with experts via interviews.

The ‘Structured Direct Observations’ approach - which is based on Space Syntax methods and includes gate counts, static snapshots, and movement traces - assumes that any effective analysis must be initiated by spending time in the space, observing how the place is used, and measuring and documenting the responses to the (intended) design criteria. These systematic observations were used in this study to count and analyse the amount, duration, and types of use involved in each COS. These were conducted at peak times for three of the five weekdays over 15 weeks. The author adopted a discreet vantage point to enable the maximum visibility of activities at three one-hour time periods (8:30 am, 12:00 noon, and 4:00 pm). All cases were studied over an eight-month period (two semesters during 2018-19) in good weather conditions. These timeframes helped to avoid any unique situations that might affect regular use (i.e. excluding days with extreme weather conditions or holidays). Activities were recorded in detail on observation data sheets which documented date, time, location, spatial features, density, and intensity for each typology, along with maps, plans and extensive field sketches/notes. These were later developed to form the COS Design Index.

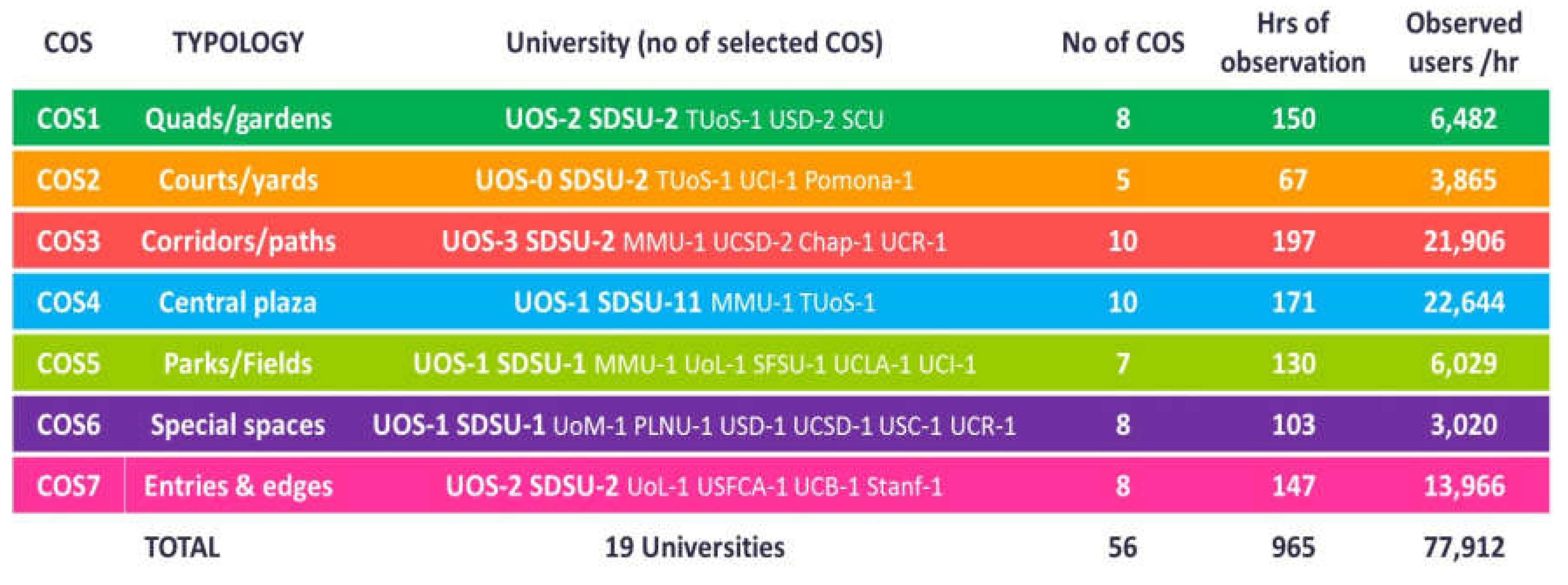

‘Unstructured Direct Observations’ were also used for specific purposes and described in detail. Here, the author often acted as a participant observer, taking sketches, field notes, short videos (30 seconds to three minutes). These were associated with walk-in interviews with students (n=138) which helped to verify behavioural patterns, student preferences, and regular uses. From the field observations across more than 30 universities (20+ in US & 15+ in the UK) comprising over 60 COSs, all student activity or outdoor experience fell into one (or more) of the following typologies (listed in

Table 1).

The walk-in interviews were followed by in depth interviews and conducted to discuss and verify the reasons why some COSs are more accessible or in higher demand by some students than others, or why students prefer to undertake a particular activity during a particular time in a particular space (or part thereof). These discussions were important because several observed uses or behaviours were not perceived as typical or intended by the campus planner.

Indicators/Measures for the COS Experience Score

The following provides a summary of the indicators (or factors) considered to calculate the performance of the student experience in relation to the COS design features (i.e. the process for calculating the overall average ‘COS Exp Score’).

- (1)

COS Profile (A1-A9). The profile starts with a general description of the university and its campus setting. This includes nine key features: University type and location, campus type, campus scale, university land area, campus capacity in terms of area and students, university rank, average tuition fees.

- (2)

COS Design Criteria (B1-B10). Identifies the ratios of 10 specific urban/landscape design features and spatial conditions including: COS area & cost, seating, enclosure (openness), circulation (density), intersections (connectivity), vegetation (useful), greenery (natural), shade (comfort), and site furniture (quality and diversity). These factors were developed from several studies, but particularly Dober (1992); Gabr, Elkadi, and Trillo (2019); Waite (2014); while the ‘visual quality’ approach was developed by Van Langelaar and Van der Spek (2010).

- (3)

-

Experience Typology (C1-C3). These factors indicate the intensity and variety of activities (indicators of the usefulness of the space). Although this does not include the diversity of the students (different ages-fields-cultures), it can indicate the degree of responsiveness of the space for different users and purposes. These users and purposes are categorized under four main experiences (individual-personal, group-social, programmed-academic, and active-energetic). Accordingly, the authors developed seven typologies of COS design (quads, courtyards, corridors/paths, plazas, playgrounds, special spaces, and edges/entries – excluding vehicle routes and parking). These were adapted from the campus masterplan data collection (Gabr et al., 2019), and include the following three key factors:

C1. Frequency of use / Density (Fu). Average users in a selected COS per hour.

C2. Duration of stay (Ds). Calculated by studying how much time is spent by how many users in each activity, which is captured under four categories: Less than 20 minutes (a corresponding score was assigned by multiplying users by 10); 21 to 40 minutes (multiply users by 30); 41 to 60 minutes (multiply by 50); 61+ minutes (multiply by 80).

C3. Intensity of use (Iu). This determines the frequency of use and duration of stay (user involvement per day) over the area of space, as calculated by the equation below:

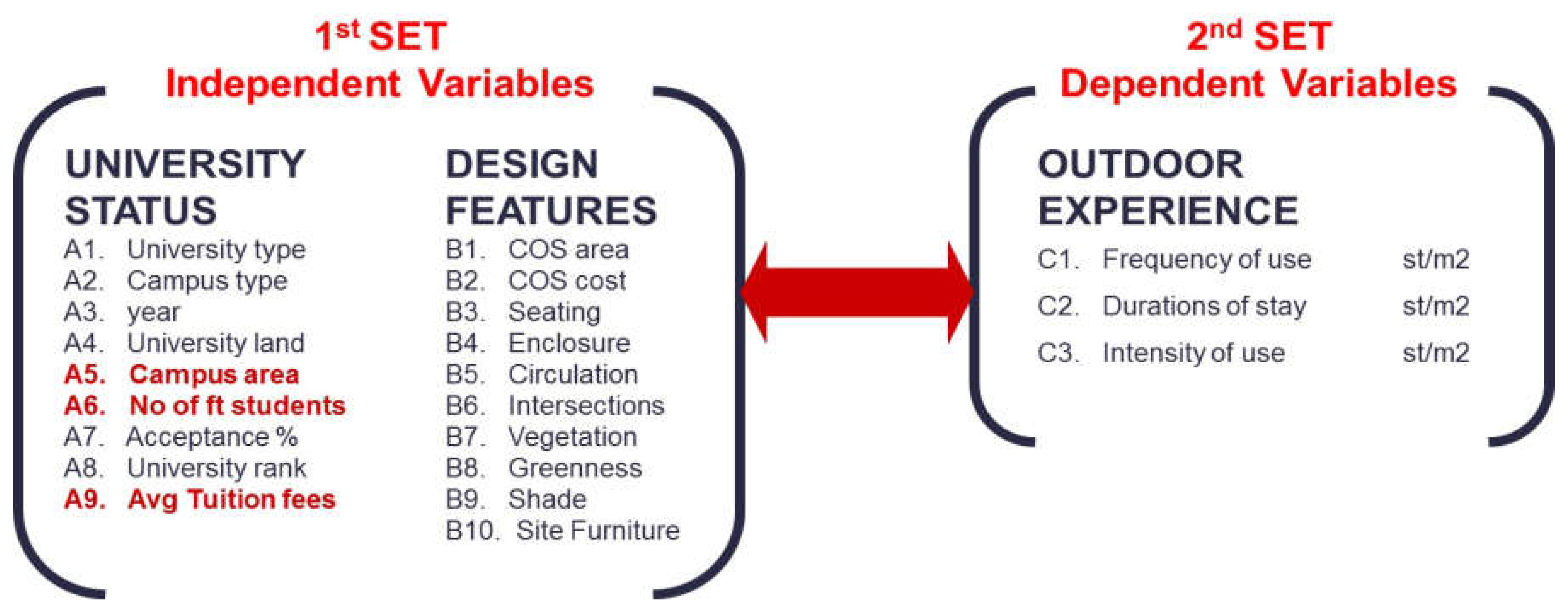

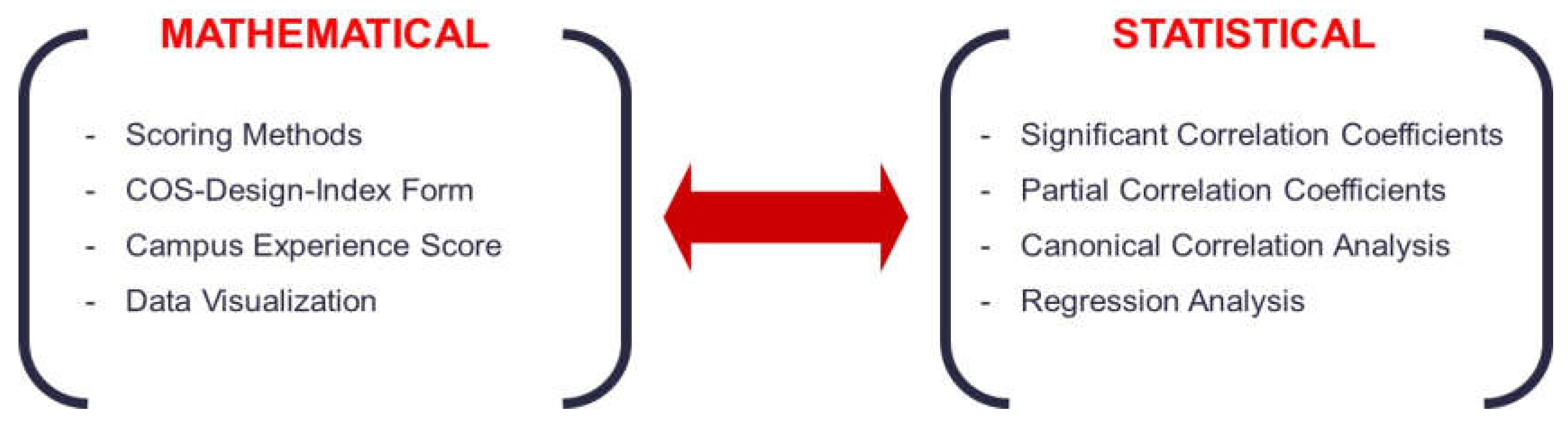

These calculations were developed from a number of urban studies; for example Gehl (2011); Gehl and Svarre (2013) verified that the overall social activity or liveliness of an environment is a product of the number of people and duration of their stay. This means that more experiences are allocated if the COS accommodates many people for a short duration or fewer people for longer. In particular, the total cost of each COS is specified by the development of the masterplan or calculated approximately based on the COS floor area, and natural and physical features (illustrated in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Figure 2 details the first set of variables shown, namely the inputs. To assure the application of common standards alongside readily available and objective information, three measures (A5, A6 & A9) were used in the calculations. These represented the ‘university status’, and were used to normalize the data compared among the COSs at different universities. The second set of variables shown represent the outputs, which were used to measure the impact of the ‘design features’ on the student experience. The two sets together represent the criteria and sub-criteria used to rate the quality of the COS design, user experience, and costs, which were compared through mathematical and statistical approaches (listed in

Figure 3).

4. Results & Discussion: Comparison of the Case Studies

Ph#1 – University Profile

A profile of the campuses and their contexts is established on three scales: Regional (relevant information about California and England), local/national (relevant information about the ‘university status’ which is reviewed in phase 1), and urban (campus and COS features reviewed in phase 2). In phase 3, this information was simplified, compared, and presented with specific indicators which were used to calculate the ‘COS exp. score’.

California and England have been selected as regions because they hold the two most populated, satisfactory, and most desired university destinations. The UK is a world leader in higher education, which can be demonstrated in its attraction to students; for example, in 2021/22, 2.75 million students (nearly 5% of total population) spent most of their time in over 132 UK universities (those eligible for national rankings) representing £30 billion of business (UK, 2018). It has the highest student retention, whereby 71% of the country’s students completed their undergraduate courses, in contrast with 49% in the US and just 31% in Australia (Indicators, 2022),. In 2011, capital expenditure on UK universities’ estates was calculated at £3.58 billion compared to around £1 billion in 1997 (over 130% inflation). Over the same period, the total number of UK students in higher education rose by around 43% between 1996/7 (at 1.76 million) and 2010/11 (at just over 2.5 million). Moreover, according to statistics gathered by the Higher Education Statistics Agency, in 2020/21, the UK also had the highest percentage of international students at 605,000. Several rankings and ratings are published on the performance of UK universities which concern their students, staff, facilities, etc. Three national UK university rankings are published annually: The Complete University Guide, The Guardian (jointly with The Times), and The Sunday Times (formerly produced by the Daily Telegraph and the Financial Times). The primary aims of the rankings are to inform potential applicants about UK universities based on a range of criteria, including entry standards, student satisfaction, staff/student ratios, academic services and facilities, expenditure per student, research quality, completion rates and student destinations, and so forth. Among 15 visited universities in the UK, the six observed universities were: University of Salford, University of Manchester, Manchester Metropolitan University, The University of Sheffield, University of Liverpool, and Huddersfield University.

In comparison, the California Higher Education system is the largest in the US, with over two million undergraduate students representing over 5% of the total population (Johnson, 2016). The state’s reputation for higher education and its ‘tech sector’ produce the most populous and most prestigious universities making it the most wanted study destination state among the US. The state has numerous world-class public and private universities (about 296 universities constituting £37 billion business) including the selected cases for this study. The US’s most popular and influential set of rankings is published by is US News and the World Report. Other reliable US sources used in this study are the National Centre for Education Statistics (NCES) and the National Student Clearinghouse. Private universities out-perform public universities in the ranking tables and enjoy a much stronger reputation academically. They usually exercise strict, very low acceptance rates to control the quality and quantity of students admitted to their programs. Their campuses and classes are smaller, and their programs are critically picked by the school administration which contrasts in approach with their public-school counterparts. Public universities offer large enrolment opportunities and lower tuition fees while often still maintaining an excellent standard of education. In California, as much as many other states, there are two main types of university systems: State universities (selected were SDSU, SFSU & SJSU from the 26 public universities available) and the University of California (selected were UC Berkeley, UC LA, UC SD, UC San Francisco, UC Irvine & UC Riverside from the 11 private universities), as well as 100+ private universities (selected were Stanford University, University of Southern California, Chapman University, Santa Clara University, Point Loma Nazarene University, and University of San Diego). These are aside from the 300+ public/state and private colleges across the USA. In total, 15 were universities selected from California (among the 19 visited universities) in addition to six universities from the UK. The difference in number between the UK and USA is attributed to the wider variety of university in California with more advanced COS designs.

Ph#2 – COS Design Index (Focused Comparative Campus Study)

The COSs were selected from each university campus as representative of the seven COS typologies of design (representing the most common design and use features of each typology). These include the analysis of the campus masterplan along with the analysis of the preliminary observations, which explored and rated 10 key parameters representing the quantity/quality of the physical design and urban qualities on a ‘COS Design Index’. The seven selected COSs represent only a small percentage and findings may therefore not be representative of all campus typologies. However, from the preliminary observations (comprising nine visits) the selected COS were the most used and/or preferred by students.

Figure 4 illustrates a list of all seven typologies observed, in which the universities, amount of COS per typology, hours of observation, and total number of observed users are shown. This is followed by a quick description and keynotes from the observations made for each COS typology.

COS1: Quads and Greens

These are the prominent natural open spaces (lawns) on the campus. They tend to be iconic and mostly native, natural landscapes which contribute to the beauty and unique character of the campus. They can be used for educational purposes and passive recreation. Gardens – as part of this typology - are also stimulating, intimate spaces to meet, relax or study (individually or within gatherings). These spaces are usually accessible yet semi-private and should be sufficiently diverse to accommodate different needs. They often contain more landscapes features, for example shelters when needed, various seats, ecosystems such as birds/nests, wilder elements such as fishes/ponds, and cultural elements such as fountain/s and sculpture/s. Secondary quads fill a variety of roles and are surrounded by formal geometric/square buildings. They provide a range of usable space, seating and other furnishings which make them suitable for study and social activities. Dramatic elements such as seasonally flowering trees can make a campus quad particularly memorable.

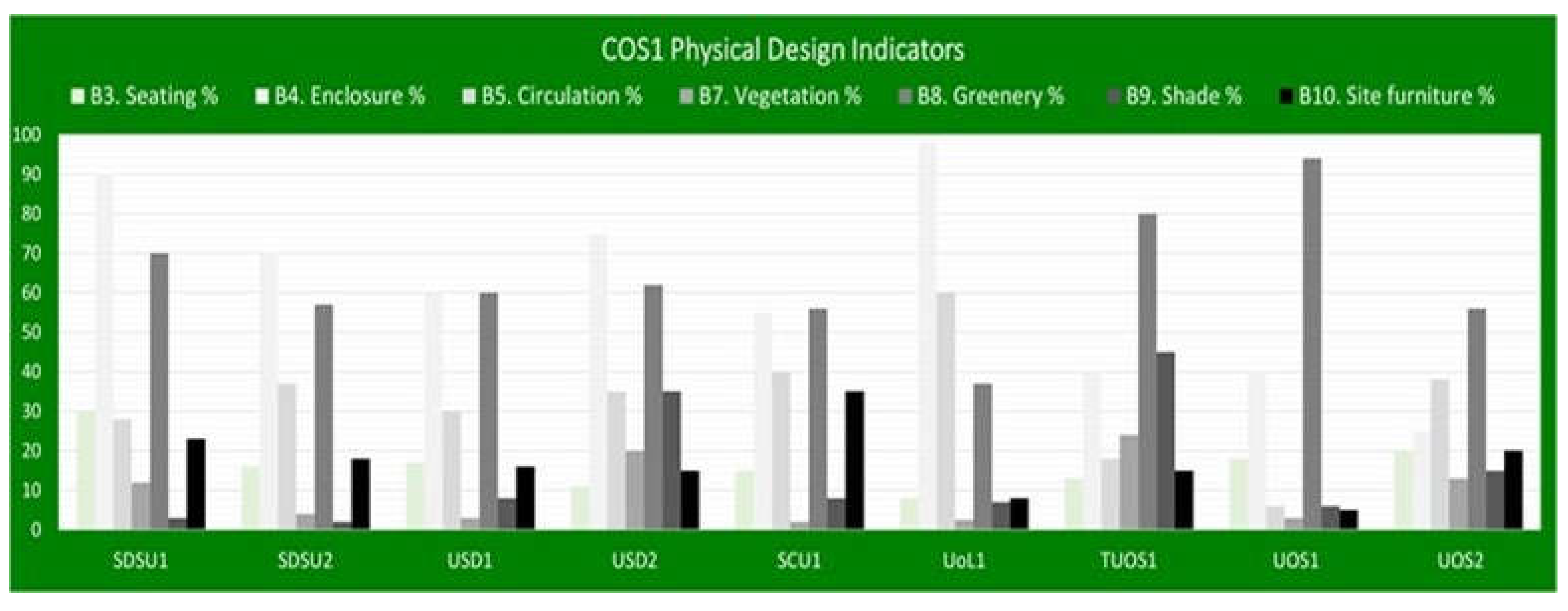

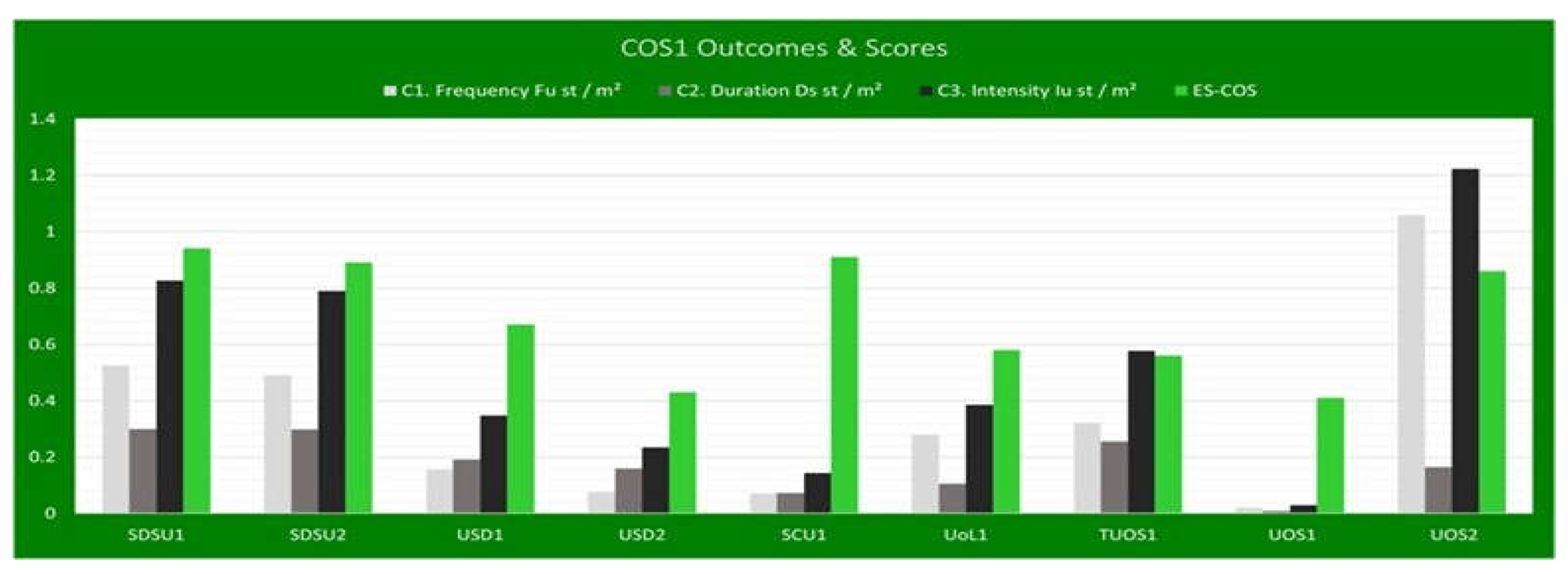

Figure 5 shows some visualization of the data for this typology in the form of ‘charts’, which was similarly done for the other six COS typologies. The charts show the rates of the 10 ‘physical design indicators’ (ph#2) and the rates of the associated outcomes, as represented in the student experience (ph#3).

COS2: Courts and Building Yards

These are areas of flat ground outside and, partly or completely, surrounded by one or more buildings. While not strictly defined as having a paved ground plane, most images of courtyards primarily show hard ground surfaces. Special attention tends to be given to seating areas and providing an academic yet welcoming environment. For example, this may mean including comfortable seating for gathering and ensuring that technology is enabled. Depending on its location and size, the design of these spaces should accommodate special academic events and be sufficiently diverse to accommodate different learning settings. In this context, features such as portable or flexible furniture, controlled areas/zones, and unique floor patterns and colours (representing the university image) are considered.

Many UK university campuses lack courtyards which are designed to allow outdoor classes, informal discussion, and quiet study. Such spaces can provide access to adjoining buildings and a restful view from neighbouring classrooms and offices. The design of courtyards tends to focus on providing a comfortable environment in virtually all seasons, with plenty of seating and a variety of opportunities for sun and shade.

COS3: Connections/Pathways/Corridors

These are typically linear spaces surrounded by and supporting the movement between academic and student life buildings. For major paths, pedestrian malls are common nowadays than typical corridors, as they are wider and larger meaning they can better provide gathering areas and accommodate a wider range of activities. Since these spaces usually involve the highest flow of students and potentially other users/guests, they may also be enhanced with new business-related stands (e.g. food stands and pop shops). These new connections are sometimes more complex to design as they need to enable greater/better walking experiences between the campus-residential-commercial spaces, and reflect a greater range of urban qualities. These qualities include: strengthening connections to improve permeability, providing a well-defined network of routes by ensuring longevity and coherence, and offering hierarchy and zoning interventions through the inclusion of conducive landscape features such as tree-lined boulevards and informative/way finding.

Efforts to improve an experienced-based campus design should focus on facilitating diverse walking paths that inspire students to use and discover new spaces or engage in new experiences. Such paths can border or surround existing active spaces and/or be created with additional landscaping features that provide different patterns to allow for different ways of commuting. They can also consider various shading strategies, interesting/guidance signs, unique points of interest, and/or schedule more regular events to encourage the engagement of students and community members. This means increasing the attractiveness and safety of sidewalks and roads around campus to encourage more students to walk at different times of the day/night and during weekends. One example of this addition is the centennial pedestrian mall (SDSU) which was developed in 2013 at a cost of $600,000 and raised funds of $1 million (as mentioned in the interview with the director of the SDSU Planning Department, 2019).

COS4: Plazas and Main Campus Squares

The central open space is a large area (semi-public square) defined by the main university buildings (library, student union, reception and administration, food court, and sometimes the oldest educational buildings). Hence, it usually involves a mixture of all elements such as learning, recreational, social, circulation while supporting other uses and facilities (such as housing bike racks, digital walls). A variety of relaxed paths may also be included to accommodate and enhance different modes of movement and activity. Central plazas are usually the biggest, richest, and most representative of the university’s image/identity. As such, top quality and significant amounts of landscaping elements are incorporated (capturing colour, scenery, topography, stage, and the largest and/or oldest landmarks) to meet the institution’s multi-faceted mission.

COS5: Parks and Playgrounds

These spaces can be part of the campus or attached to it, and tend to be set aside for the display, cultivation and enjoyment of plants and other forms of nature. Playgrounds can form part of the parks or included in separate built fields. Similarly, parks also incorporate both natural and manmade recreational areas which may exhibit structural enrichment such as water features, statuary, arbors, and so forth. A campus design should bond connections to a park by creating more positive edges and facilitating a more diverse range of activities (extended lawns, outdoor gyms, creative landforms). Primary campus open spaces are often among the most memorable elements and the most used buildings on campus; moreover, they have been found to be a key factor in the students’ evaluation of a campus.

COS6: Special Spaces

These spaces are unique with very specific environments supporting certain function/s. They can incorporate a specific typology of any of the other typologies, for example a theme or scientific park, outdoor learning lab, outdoor theater, intimate or relaxed space, or outdoor classrooms. These represent the newest COS typology and the most private spaces (sometimes used only for certain occasions or seasonal interest). Usually composed of a special mixture of architecture, landscape, and signage they provide subtle yet iconic demarcations of campus spaces.

COS7: Edges, Entries and Gateway Plazas

These spaces represent the campus entrances and/or its edges and boundaries. Usually, a campus is encircled with public or semi-public spaces which are transformational spaces used as the main points of entry/gateway from the neighboring communities. The campus benefits from a stronger entry sequence and sense of arrival on campus (i.e. iconic demarcations of campus boundaries represent the campus image or identity). The majority of campus developments concern the renovation of arrivals and exploiting character/identity. They tend to consider qualities such as the approach, visual and pedestrian access, drop off, and pick up. They can also incorporate a unique gateway experience with a key landmark and distinctive lawns/planting, and are sometimes also used for outdoor gigs, concerts, events or exhibitions.

Ph#3 – COS Exp Score (Experience & Cost)

After rating the quality of a COS design and its costs, the students’ responses or actions were measured to explore the extent to which the COS facilitated activity and social interaction, otherwise known as placemaking. Data from all selected universities and COSs, along with findings from the quantitative calculations, were input into Excel sheets within the ‘assessment model’. The assessment model produced the ‘COS exp score’, and a higher ‘COS exp score’ signified whether the space tended towards the:

‘Most used’ - COS with the highest frequency of use ‘footfall’. These spaces were usually the most important and most known on the university.

‘Best used’ - COS with the highest duration of stay, a ‘student-friendly space’. These spaces are usually the most satisfactory for some of the students as they were successful in facilitating one or more of the following practices: Standing around, gathering, eating, chatting, relaxing, playing, studying, stopping, passing through, or looking around. They allowed students to pause between movements, collect their thoughts, interact, or simply take a moment to relax.

‘Most valued’ - or most beneficial spaces. These were different from the ‘best used’ spaces as they offered advantages to a wider range of beneficiaries aside from students, and had greater impacts on the student experience. For example, this included COSs that were designed to expose students to staff, community, and ideas in more innovative ways. They included: the development of living labs within wildlife gardens; civic and cross-functional spaces with informal seating niches and recycling programs; recreational spaces with interesting athletics; innovation hubs with high-tech features, private-market spaces with entrepreneurial practices, etc, all can contribute to the environment, community, businesses/market and the industry in different ways. At the University of Salford, renovating the Irwell River for example, represents an area of great investment and will add more integrative activities for students and the community.

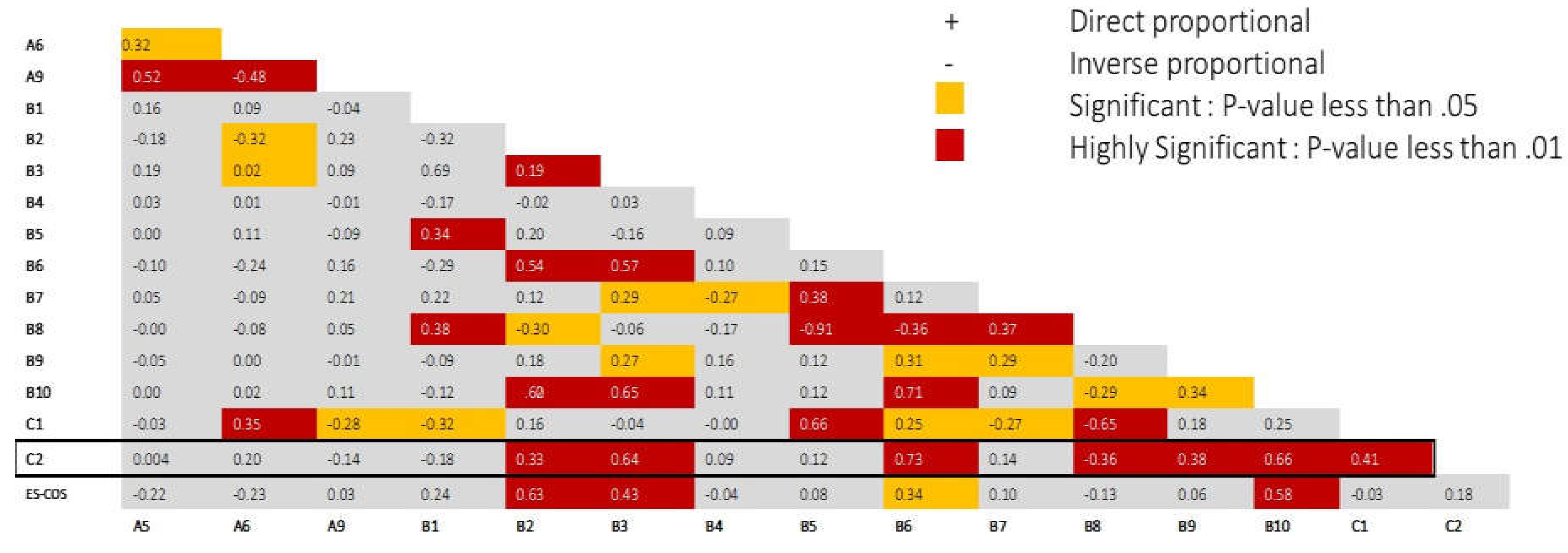

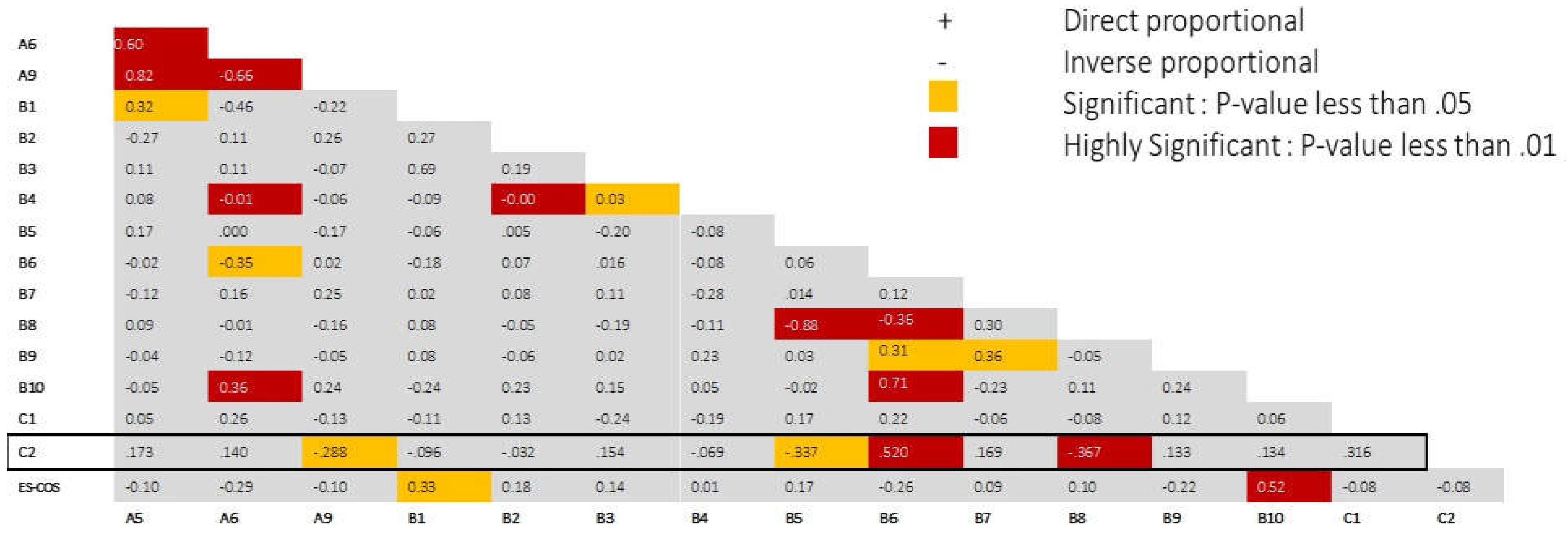

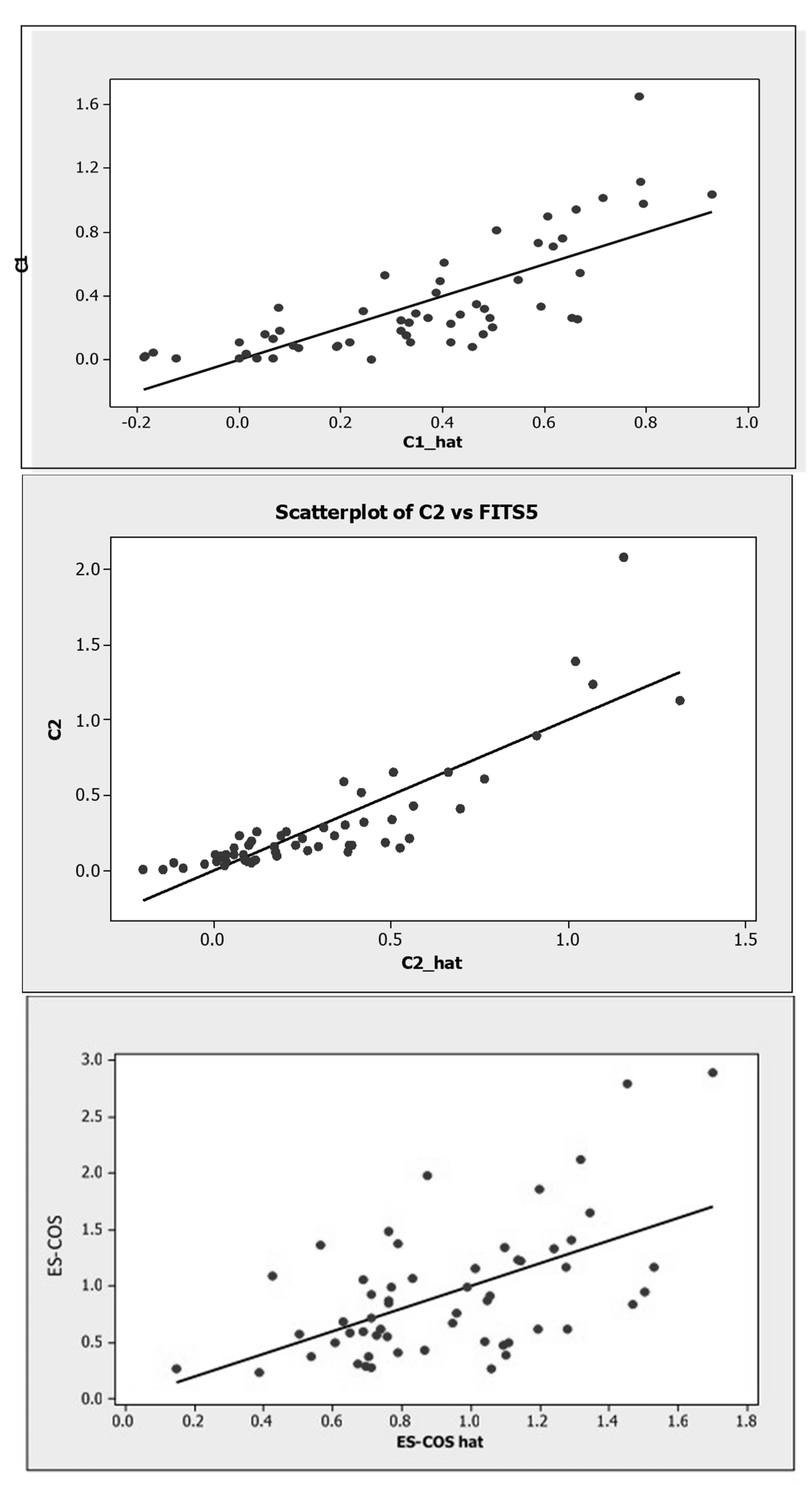

The relationships between the variables (inputs and outputs) were tested using four statistics methods. For example,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the correlation analyses, which were used to measure how much the variables are linearly associated or correlated with each other. The most correlated (highly significant) variables with C2 (duration) are, in descending order: B6, B10, B3, B9, and B2. These variables are directly proportional while B8 has the only inverse proportional correlated value.

The Canonical Correlation Analysis was another statistics test used to provide a linear relationship between the variables (

Table 2). The first set shows the highest correlation between the two pairs, which was determined by finding the linear combination of the matrices. The pairs of linear combinations are called the canonical variables (C.V.). The C.C. (Canonical Correlation) measures the strength of association between the two sets of variables through their C.V.

Figure 8 shows the regression analysis - the last statistical technique used to investigate and model the relationship between variables so that the variable can be predicted when examined in another setting. As such, if C1 represents the dependent or response variable and A5, A6, … B10 represent the independent or predictor variables, then the best subset multiple coefficients can be interpreted as, for example, the points of intersection (B6) which increases by 1 unit (1 point/100 m²) as C1 increases by 0.269. There are only four significant predictor variables, which result from the best subset regression equation of the response variable (C1) versus the 13 predictor variables with significant coefficients.

A composite score (ES-COS) was developed using the afore mentioned formula in the COS design index. The correlation analysis and ranking scores revealed the matches and gaps within campus type, or context, and/or for each COS typology. The top frequency rates were found at the linking steel bridge at SDSU (1.65) which sees 30,000 students passing through the academic day; this was followed by three corridors in three other campuses. The three top duration rates were seen in the following COS typologies: special/inspired spaces (COS6) and central plazas (COS3). The three dimensions with highest direct proportions (correlations) to each other were B6 (intersections), B10 (site furniture), and C2 (duration). While the two most inversely proportional variables were B5 (circulation) and B8 (greenery).

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Recommendations

This study provides new valuation methods ‘COS exp score’ which account for intangible urban variables such as campus urban qualities (walkability, accessibility, integration, and connectivity) which contribute to the student experience. The valuation scores present an integrative evidence base across a COS’s quality of design, use, and cost/value by applying mathematical and statistical methods that calculate quantitative indicators (e.g. frequency and intensity of use). The criteria academia-university, campus urban and landscape design, and costs-value.

Ranking scores indicate student preferences for COSs. The valuation methods and rating scores were developed via the observations and expert interviews, then tested on a total on 21 university campuses (six selected universities from the UK, and 15 from California in the USA). From the assessment and analysis, the highest frequency usually indicates the ‘Most-Used COS’, and the highest duration indicates the ‘Best-Used COS’, while the ‘Most-Valued’ indicates the most beneficial with most added values to students and beyond. These ranking scores take into account three key impacts of a quality COS design: Students (to enhance experiences and success), the university (to deliver its objectives), and business (to enable greater awareness of appropriate levels of investment). Accordingly, three specific sets of recommendations are listed below for academia (university, staff and students), estates departments in universities, and planners. The recommendations reinforce and enhance an understanding of the impacts of design and cost on the outcomes of campus outdoor development.

Recommendations to Academia – towards a Student-Centred COS

From an educational perspective, and specifically considering the student experience, the university vision should be monitored to check how it is being implemented, and how developers and planning applicants are responding to enhance the student experience. Based on the student responses in this study (success and satisfaction), a university’s planning and/or integrative assessment may need to be reviewed, as well as its marketing and investment tactics.

There are so many ways to add to the future of student life and their success to ensure spaces evolve with what is needed for comfort and productivity. One approach to increase student satisfaction is to make the campus a place where students want to spend time. If students feel compelled to stay, they can contribute positively to campus culture and have a fulfilling experience that prepares them for professional success. Meeting student satisfaction leads to a healthy state of mind, higher academic performance, and more positive outcomes during their study and after graduation. Health impacts our everyday functions and the ability for both students and a faculty to learn. As such, universities should consider strategies and activities, and seek environments that add value/s in caring for our physical and mental well-being.

Like the UK, an essential part of US rankings concerns students’ opinions, ensuring their satisfaction, and meeting their expectations. Current students and alumni annually provide feedback about their thougts on the institution, their life on- and off-campus, and their satisfaction with several key aspects including campus facilities, extracurricular activities, and financial provision.

As the student experience contributes to their success and satisfaction, the correlation, conflict, and links between the indoors/outdoors and formal/informal should be regularly monitored and reviewed. Academia should monitor student behaviours and their movement within campus (student responses to their needs and surroundings). For example, this includes noting when students meet/gather or need privacy, avoid or interact, eat or chat, study or discuss, play or relax, and for other positive or negative activities and reactions. Among the analysis of all observed typologies, the students mostly gather at food and beverages areas - over 50% of all other campus spaces - followed by the central plazas (30%). The longest durations of stay were recorded at the special spaces ‘COS6’, followed by the central plazas ‘COS4’. The Most-Used and Best-Used COSs (highest ‘Frequency’ & ‘Duration’) compete for students’ attention, and could achieve more if undertaken with direction from, and by meeting, the university’s academic missions. The Most-Valued COS seems more complicated to design, assess, and integrate with university missions concerning its wider impacts and added values (e.g. to create a better and more memorable student experience). Diversity in COS typologies of design and use can meet more diverse student needs which may be associated with particular sensations and/or physical responses (learning-mental, social-behavioral, emotional-personal, physical-active).

Recommendations to University Estates – towards a Value-Based Assessment

Estates - who typically guide, control, and/or manage the design and evaluation of COS quality and use - should facilitate more collaborative/integrative assessment methods among all parties (how effectively stakeholders work together) to resolve potential conflict. As such, this assessment should be informed by and incorporate data from different parties on students’ needs and activities. It should also consider opportunities and challenges associated with the local context, as well as the constraints of the university in terms of future investments (e.g. higher campus values and involving the public attention).

Higher education spending on luxurious campus facilities gives the impression that students are only attracted to ‘lavish campus details’. While this may be true of some universities and students, it is also noted that certain COSs are significantly improved when provided with high quality features and rich environments. However, this is not always the case and can be sometimes mean unnecessary spending on resources, and thus damage an otherwise experience-based and educationally sound rationale for campus development. Universities that invest too much in expensive campus projects may be putting themselves at risk, particularly considering current challenging worldwide economics. Recently, a growing number of colleges and universities have become aware of that possibility and are moving away from trophy buildings and other seemingly excessive amenities. Rather than solely investing in expensive design features that can sometimes create financial and public-relations risks, universities should focus on integrating the assessment of different COS typologies that better serve the overall academic context/environment. For example, ‘Greenness’ was found to have the biggest influence on the student’s ‘learning’ experience (quiet and pleasant environment), while ‘Circulation’ had the smallest. This shows that the correlation analysis among the COS design features and their impacts - when carefully manipulated - can add value to students and the university.

Moreover, estates can integrate this assessment with the strategies of campus investment that consider the best fit for life both during and after university. This could be inspired by innovative business solutions and services that significantly support and advance the needs of a diverse and dynamic campus community. The central plazas for example, offer a wide range of activities through the design of an economically and socially viable environment. As such, the ‘Location/Centrality’ was scored the most important urban quality in terms of the frequency of visits regardless of the purpose of the visit (whether the user was just passing by or through, or the COS was the destination).

Recommendations to Planners – towards an Experience-Driven Design

Adequate planning, design and assessment at different scales and stages maximizes the benefits of a COS. As university planners seek to develop the campus’s public realm, they should also aim to respond to student needs and enhance their experience on campus by integrating and examining the tangible and intangible design aspects to enable a better performance (e.g. access to better quality spaces and a greater range of amenities/facilities). In terms of students’ needs and satisfaction, planners should also aim to strengthen campus life through the development of centres of activity, including mixed use, commercial retail, and cultural and recreational facilities that promote social interaction on campus and bring the off-campus community onto the campus. Within this context, integrating this assessment with the planning process can guide or explore the links and conflicts among the COS typologies. For example, the results of the assessment have shown a negatively correlated relationship (i.e. inversely proportional) between COS Greenness (the areas of lawns and the levels of dense and decorative vegetation) and Circulation. However, both indicators are positively correlated with the outcome variables (frequency and intensity of use). This means that these two design features – although opposing scores – have the greatest impacts on the quantity and quality of the other design elements. Utilizing the ratios of Greenness and Circulation can also significantly distinguish between the COS typologies (formal/structured versus informal, or completely green or natural versus paved corridors). Nonetheless, such uses are not only dependent on urban and design qualities but can also be influenced by other variables such weather conditions, the urban and cultural context, the period of the academic year and the year of study, and student mode.

Planners should also prioritize design features specific to a COS typology as it is not possible to apply all quality parameters everywhere in the same way and in the same order, i.e. creating designs that facilitate all possible forms of experience, engaging, smart, natural, sustainable, welcoming, attractive, active, and quiet qualities. Some typologies need more active areas or to be open to the community while others need more quiet environments or opportunities for more private/personal use. Moreover, some need to be natural or strongly connected to nature while others need to be smart and support high-tech features; in addition, some should enable higher frequencies of use while others may require less frequency yet longer durations of stay. A clear finding that diversity is not preferred across all COS typologies is based on the outcome that special spaces ‘COS6’ along with the courtyards ‘COS2’ scored the highest levels of interaction to promote learning. To prioritize appropriate criteria, a well-managed design policy for the COS needs to be developed and linked with the curriculum, and rather be responding to the students’ backgrounds, needs, expectations and diverse experiences. The analysis also shows that among the 10 physical design features, the duration of stay in COSs mostly correlate to the number of intersections (B6) and the amount and quality of site furniture (B10).

Indeed, as typologies of COS vary according to their design and use, different stakeholders are likely to have very different motivations and perceptions, and are not fixed in time. Academic staff or students may have very different perceptions of what makes a good campus environment, from the university estate itself or a development charged with preservation and added value/s. In this regard, a broad range of stakeholders with varying backgrounds should be involved in making, using and managing campus developments, which in turn, will enable the expression and discussion of opposing viewpoints. The significance and level of stakeholder involvement in the planning process are majorly determined by the planner and the nature of the planning model. The campus planner may best know what sorts fit academic, entrepreneur or ecological environments for the benefits of students’ experience and satisfaction.

Campus planners can develop a more innovative and successful campus when keeping, developing and regularly assessing the elements of uniqueness and sense of place in their master plans while simultaneously following common models of practice. To some extent, designing a diverse COS may challenge the distinct character and identity of a campus. Campuses may also have similar identities if planners only adopt generic recommendations set by the state, government, HE, and/or university guidance. Strong personal and academic identity can be both promoted by not solely preserving symbolic parts on campus, such as historic buildings, rivers/lakes, and landmarks, but also by creating meaningful campus environments with a sense of charm and warmth (place-making). Place making can be developed through the use of both distinctive individual characteristics and the universal elements of a campus. From the analysis, 'flexibility’ (in design and design elements) is the most important factor to facilitate for the Best-Used COS with the lowest cost, followed by the ‘level of privacy’ (openness). Such highly universal features and values give the COS and wider university campus individuality and create the sense or support the use/s it needs. Examples of these features include towers/gates or landmark entrance spaces, avenues of trees, pocket parks, spacious footpaths, symbolic central plazas, distinctive landscapes and the proportions of spaces formed by these as a whole. It can also include many other elements found in an individual campus/COS that characterizes its individuality through points, lines, planes, as well as use/experience. Re-assessment assures that such historical or distinctive elements hold or conform to the educational, social, and investment values used for the vision/development.

Campus planners should consider offering a greater number of organized activities that promote moderate physical activity for students’ families, the community, and seniors. This indicates that experience-based design and assessment inform the design of COSs to establish positive interactions among academic, cultural, social, and physical activities. Furthermore, the most important interchanges or nodes should serve as focal points or gateways to the campus (e.g. main roundabouts, junctions, footpaths) which should be marked by a change of, or larger and diverse, uses. This promotes the concept that a campus represents a living-learning resource that is integral to the University’s mission, namely to protect and enhance the campus identity, image, beauty, and benefits.

References

- Beetham, H. (2007). An approach to learning activity design. Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age: Designing and delivering e-learning, 26-40.

- Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain. New York: McKay, 20, 24.

- CABE, D. (2000). By Design. Urban Design in the Planning system.

- Calvo-Sotelo, P. C. (2012). Urban & architectural models for innovative education. Paper presented at the International Conference on the Future of Education. 2nd conference edition.

- Calvo-Sotelo, P. C. (2014). From typological analysis to planning: modern strategies for university spatial quality. CIAN-Revista de Historia de las Universidades, 17(1), 31-58.

- Chapman, M. P. (2006). American places: In search of the twenty-first century campus: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Conyne, R. K., & Clack, R. J. (1981). Environmental assessment and design: A new tool for the applied behavioral scientist: Praeger publishers.

- Coulson, J., Roberts, P., & Taylor, I. (2017). University trends: Contemporary campus design: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Desrochers, D. M., & Wellman, J. V. (2011). Trends in College Spending 1999-2009. Where Does the Money Come from? Where Does It Go? What Does It Buy? A Report of the Delta Cost Project. Delta Project on Postsecondary Education Costs, Productivity and Accountability.

- Dober, R. P. (1992). Campus design: Wiley.

- Dober, R. P. (2000). Campus landscape: functions, forms, features: John Wiley & Sons.

- Eckert, E. (2012). Assessment and the outdoor campus environment: using a survey to measure student satisfaction with the outdoor physical campus. Planning for Higher Education, 41(1), 141.

- Francis, M. (2003). Urban open space: Designing for user needs: Island Press.

- Gabr, M., Elkadi, H., & Trillo, C. (2019). Recognizing greenway network for quantifying students experience on campus-based universities: assessing the campus outdoor spaces at San Diego State University. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Fábos Conference on Landscape and Greenway Planning: Vol. 6, Article 51. [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J. (2011). Life between buildings: using public space: Island Press.

- Gehl, J., & Svarre, B. (2013). How to study public life: Island press. [CrossRef]

- Hanan, H. (2013). Open space as meaningful place for students in ITB campus. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 85, 308-317. [CrossRef]

- Indicators, O. (2022). Education at a Glance 2022: OECD Publishing.

- Johnson, H. P. (2016). Higher education in California: Public Policy Instit. of CA.

- Kenney, D. R., Dumont, R., & Kenney, G. (2005). Mission and place: Strengthening learning and community through campus design: Praeger.

- Klassen, M. L. (2001). Lots of fun, not much work, and no hassles: Marketing images of higher education. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 10(2), 11-26. [CrossRef]

- Kuh, G. D. (1995). The other curriculum: Out-of-class experiences associated with student learning and personal development. The Journal of Higher Education, 66(2), 123-155. [CrossRef]

- Lau, S. S., & Yang, F. (2009). Introducing healing gardens into a compact university campus: design natural space to create healthy and sustainable campuses. Landscape Research, 34(1), 55-81. [CrossRef]

- Lau, S. S. Y., Gou, Z., & Liu, Y. (2014). Healthy campus by open space design: Approaches and guidelines. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 3(4), 452-467. [CrossRef]

- Lippman, P. (2002). Understanding activity settings in relationship to the design of learning environments. CAE Quarterly Newsletter.

- Mai, L.-W. (2005). A comparative study between UK and US: The student satisfaction in higher education and its influential factors. Journal of marketing management, 21(7-8), 859-878. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C. C., & Francis, C. (1997). People Places: Design Guidlines for Urban Open Space (2, illustrated ed.): John Wiley & Sons.

- McFarland, A., Waliczek, T., & Zajicek, J. (2008). The relationship between student use of campus green spaces and perceptions of quality of life. HortTechnology, 18(2), 232-238. [CrossRef]

- McLeod, S. (2007). Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Available from internet: http://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html.

- Palacio, A. B., Meneses, G. D., & Pérez, P. J. P. (2002). The configuration of the university image and its relationship with the satisfaction of students. Journal of Educational administration. [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, E. T., Ethington, C. A., & Smart, J. C. (1988). The influence of college on humanitarian/civic involvement values. The Journal of Higher Education, 59(4), 412-437. [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How College Affects Students: A Third Decade of Research. Volume 2: ERIC.

- Strange, C. C., & Banning, J. H. (2001). Educating by Design: Creating Campus Learning Environments That Work. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series: ERIC.

- Strange, C. C., & Banning, J. H. (2015). Designing for learning: Creating campus environments for student success: John Wiley & Sons.

- Suttell, R. (2007). The changing campus landscape: Buildings.

- Temple, P., Callender, C., Grove, L., & Kersh, N. (2016). Managing the student experience in English higher education: Differing responses to market pressures. London Review of Education, 14(1), 33-46. [CrossRef]

- Thanassoulis, E., Kortelainen, M., Johnes, G., & Johnes, J. (2011). Costs and efficiency of higher education institutions in England: a DEA analysis. Journal of the operational research society, 62(7), 1282-1297. [CrossRef]

- UK, U. (2018). Higher education in facts and figures 2018: Universities UK London.

- Van Langelaar, T., & Van der Spek, S. (2010). Visualising pedestrian flow using PGS tracking to improve inner city quality.

- Waite, P. (2014). Reading campus landscapes. The Physical University: Contours of space and place in higher education, 72-83.

- Woolley, H. (2003). Urban open spaces: Taylor & Francis.

- Zimring, C. (1982). The built environment as a source of psychological stress: impacts of buildings and cities on satisfaction and behavior. Environmental stress, 151-178.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).