Submitted:

18 April 2023

Posted:

19 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Economic Importance of Ammonia

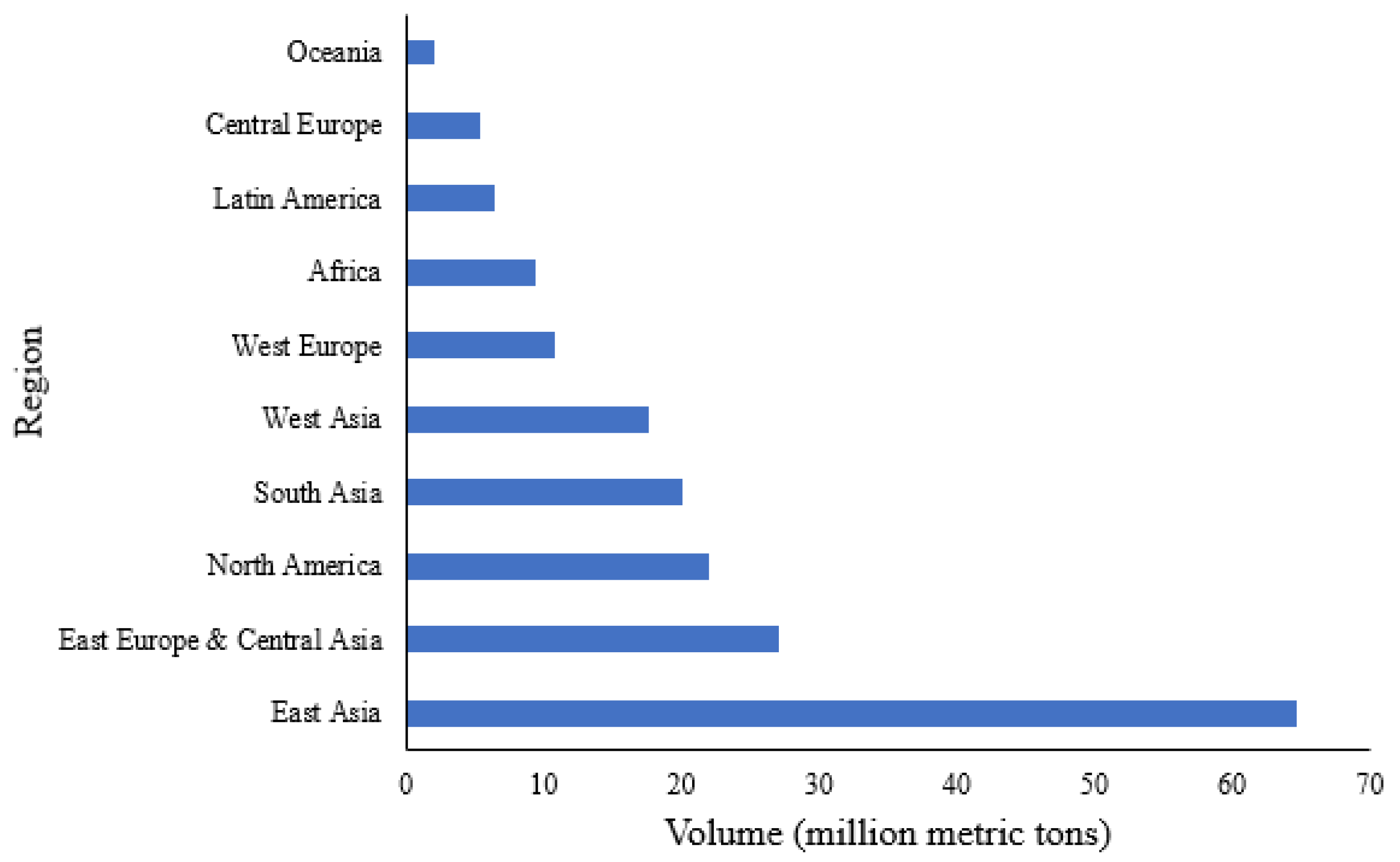

2.1. Scale of production

2.2. Application as fertilizer

2.3. Fuel potential

3. Ammonia Classification

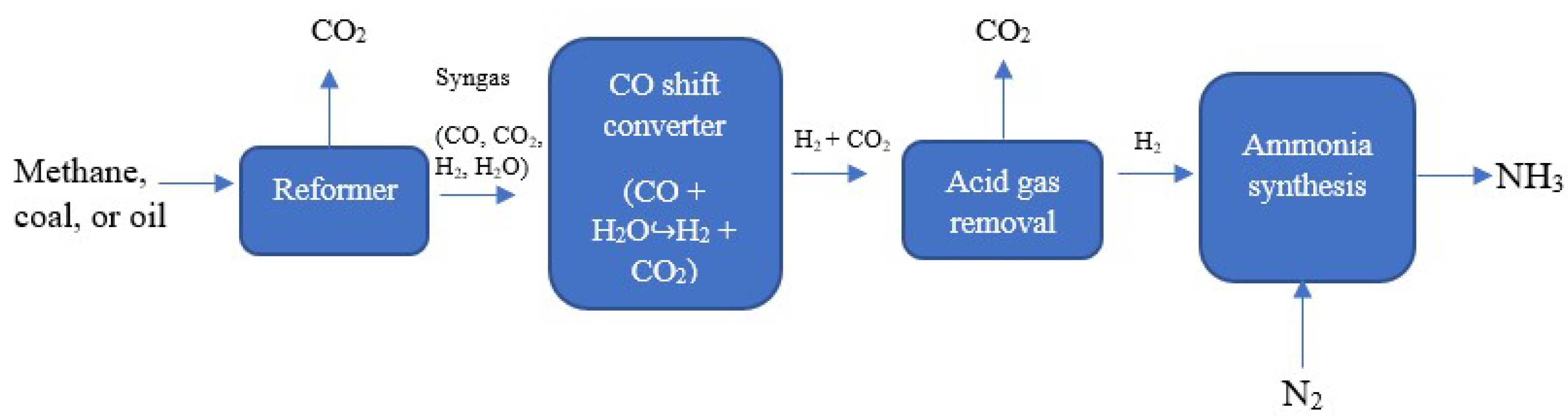

3.1. Brown (or Grey) ammonia

3.2. Blue Ammonia

3.3. Green Ammonia

4. Biological Ammonia Production

4.2. Cell and Metabolic Engineering for Ammonia Production

4.3. Hyper ammonia-producing bacteria route

5. Developing Biological Ammonia Biomanufacturing

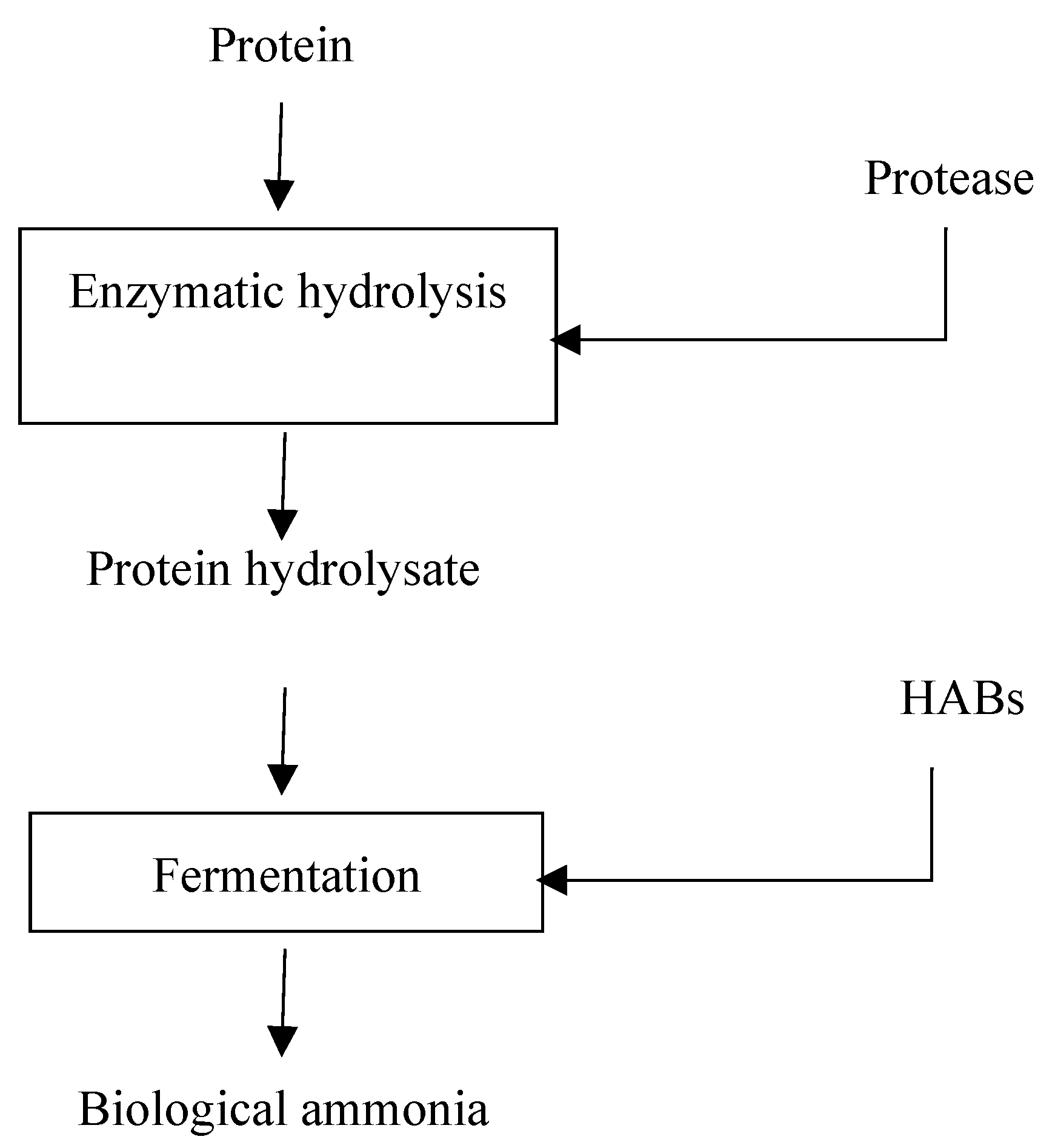

5.1. Conceptual bioprocess flow

5.2. Protein Hydrolysis

5.2.1. Biological/Enzymatic Protein Hydrolysis

5.2.2. Multi-enzymatic Hydrolysis

5.3. Leading HABs for Biological Ammonia Production

5.4. Factors affecting biological ammonia production

5.4.1. Effect of diet, substrate, and substrate combination

5.4.2. Effect of pH

5.4.3. Effect of Temperature

5.4.4. Effect of Agitation

5.4.5. Effect of time

5. Conclusions

Funding

References

- MDA Physical and Chemical Properties of Anhydrous Ammonia.

- IIAR Ammonia Data Book; 2nd Editio.; International Institute of Ammonia Refrigeration: Alexandria, VA, 2008; ISBN 1635473500, 9781635473506.

- Smith, C.; Hill, A.K.; Torrente-Murciano, L. Current and Future Role of Haber-Bosch Ammonia in a Carbon-Free Energy Landscape. Energy and Environmental Science 2020, 13, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smil, V. Enriching the Earth: Fritz Haber, Carl Bosch, and the Transformation of World Food Production; MIT press, 2004. F: the Earth.

- Liu, B.; Manavi, N.; Deng, H.; Huang, C.; Shan, N.; Chikan, V.; Pfromm, P. Activation of N2 on Manganese Nitride-Supported Ni3 and Fe3 Clusters and Relevance to Ammonia Formation. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2021, 12, 6535–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, C.; Lamprecht, R.E.; Marushchak, M.E.; Lind, S.E.; Novakovskiy, A.; Aurela, M.; Martikainen, P.J.; Biasi, C. Warming of Subarctic Tundra Increases Emissions of All Three Important Greenhouse Gases–Carbon Dioxide, Methane, and Nitrous Oxide. Global Change Biology 2017, 23, 3121–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norskov, J.; Chen, J.; Bullock, M.; Chirik, P.; Chorkendorff, I. Sustainable Ammonia Synthesis. DOE Roundtable Report 2016, 2–2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Van, J.; Maréchal, F.; Desideri, U. Techno-Economic Comparison of Green Ammonia Production Processes. Applied Energy 2019, 114135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavam, S.; Vahdati, M.; Wilson, I.G.; Styring, P. Sustainable Ammonia Production Processes. Frontiers in Energy Research 2021, 9, 580808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, L. Ammonia Production Worldwide from 2010 to 2021 Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1266378/global-ammonia-production/#:~:text=In 2021%2C the global production,approximately 64.6 million metric tons.

- Pfromm, P.H. Towards Sustainable Agriculture : Fossil-Free Ammonia Towards Sustainable Agriculture : Fossil-Free Ammonia. 2017, 034702. [CrossRef]

- FAO, F. World Fertilizer Trends and Outlook to 2020. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2017.

- Bird, F.; Clarke, A.; Davies, P.; Surkovic, E. Ammonia: Zero-Carbon Fertiliser, Fuel and Energy Store; KBR Inc.: London, 2020; ISBN 9781782524489. [Google Scholar]

- Papavisasam, S. Oil and Gas Industry Network. In Corrosion Control in the Oil and Gas Industry; 2014; pp. 41–131.

- Paschkewitz, T.M. Ammonia Production at Ambient Temperature and Pressure, University of Iowa, 2012.

- Boerner, L.K. Industrial Ammonia Production Emits More CO2 than Any Other Chemical-Making Reaction. Chemists Want to Change That. Chem. Eng. News 2019, 97, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yüzbaşıoğlu, A.E.; Tatarhan, A.H.; Gezerman, A.O. Decarbonization in Ammonia Production, New Technological Methods in Industrial Scale Ammonia Production and Critical Evaluations. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussin, F.; Aroua, M.K. Recent Trends in the Development of Adsorption Technologies for Carbon Dioxide Capture: A Brief Literature and Patent Reviews (2014–2018). Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 253, 119707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkareem, M.A.; Lootah, M.A.; Sayed, E.T.; Wilberforce, T.; Alawadhi, H.; Yousef, B.A.A.; Olabi, A.G. Fuel Cells for Carbon Capture Applications. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 769, 144243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamble, A.R.; Patel, C.M.; Murthy, Z.V.P. A Review on the Recent Advances in Mixed Matrix Membranes for Gas Separation Processes. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 145, 111062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutch, G.A.; Qu, L.; Triantafyllou, G.; Xing, W.; Fontaine, M.L.; Metcalfe, I.S. Supported Molten-Salt Membranes for Carbon Dioxide Permeation. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2019, 7, 12951–12973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, R.M.; Freitas, G.R.; Peixoto, H.R.; Nascimento, J.F.D.; Musse, A.P.S.; Torres, A.E.B.; Azevedo, D.C.S.; Bastos-Neto, M. Carbon Dioxide Capture by Pressure Swing Adsorption. Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 2182–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, I.; Rasaq, N.; Adeniyi, A.; Hammed, A. Enzyme Aided Processing of Oil. International Journal of Halal Research 2021, 3, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavam, S.; Vahdati, M.; Wilson, I.A.G.; Styring, P. Sustainable Ammonia Production Processes. Frontiers in Energy Research 2021, 9, 580808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.A.; Bouzek, K.; Hnat, J.; Loos, S.; Bernäcker, C.I.; Weißgärber, T.; Röntzsch, L.; Meier-Haack, J. Green Hydrogen from Anion Exchange Membrane Water Electrolysis: A Review of Recent Developments in Critical Materials and Operating Conditions. Sustainable Energy and Fuels 2020, 4, 2114–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Weng, W.; Xiao, W. Electrochemical Synthesis of Ammonia in Molten Salts. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2020, 43, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ji, X.; Ren, X.; Ma, Y.; Shi, X.; Tian, Z.; Asiri, A.M.; Chen, L.; Tang, B.; Sun, X. Electrochemical Ammonia Synthesis via Nitrogen Reduction Reaction on a MoS2 Catalyst: Theoretical and Experimental Studies. Advanced Materials 2018, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casallas, C.; Dincer, I. Assessment of an Integrated Solar Hydrogen System for Electrochemical Synthesis of Ammonia. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 21495–21500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddey, S.; Badwal, S.P.S.; Kulkarni, A. Review of Electrochemical Ammonia Production Technologies and Materials. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 14576–14594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frattini, D.; Cinti, G.; Bidini, G.; Desideri, U.; Cioffi, R.; Jannelli, E. A System Approach in Energy Evaluation of Different Renewable Energies Sources Integration in Ammonia Production Plants. Renewable Energy 2016, 99, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, E.S.; Peters, J.W. New Insights into the Evolutionary History of Biological Nitrogen Fixation. Frontiers in Microbiology 2013, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarnalakshmi, K.; Yadav, V.; Murugeasn, S.; Dhar, D. Biofertilizers for Higher Pulse Production in India : Scope, Accessibility and Challenges. Indian Journal of Agronomy 2016, 61, 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Khosro, M.; Yousef, S. Bacterial Biofertilizers for Sustainable Crop Production : A Review. Journal of Agricultural and Bological Science 2012, 7, 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Rapson, T.D.; Wood, C.C. Analysis of the Ammonia Production Rates by Nitrogenase. Catalysts 2022, 12, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, K.; Mousavi, S.A. Effectiveness of Nitrogen Fixation in Rhizobia. Microbial Biotechnology 2020, 13, 1314–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Lemanceau, P.; Van Der Putten, W.H. Going Back to the Roots: The Microbial Ecology of the Rhizosphere. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2013, 11, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temme, K.; Zhao, D.; Voigt, C.A. Refactoring the Nitrogen Fixation Gene Cluster from Klebsiella Oxytoca. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2012, 109, 7085–7090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Torrejón, G.; Burén, S.; Veldhuizen, M.; Rubio, L.M. Biosynthesis of Cofactor-Activatable Iron-Only Nitrogenase in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Microbial Biotechnology 2021, 14, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takimoto, R.; Tatemichi, Y.; Aoki, W.; Kosaka, Y.; Minakuchi, H.; Ueda, M.; Kuroda, K. A Critical Role of an Oxygen-Responsive Gene for Aerobic Nitrogenase Activity in Azotobacter Vinelandii and Its Application to Escherichia Coli. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xu, A.; Elmerich, C.; Ma, L.Z. Biofilm Formation Enables Free-Living Nitrogen-Fixing Rhizobacteria to Fix Nitrogen under Aerobic Conditions. ISME Journal 2017, 11, 1602–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.; Feng, P.C.C.; Pitkin, J. Methods and Compositions for Improving Plant Health 2014.

- Yenigün, O.; Demirel, B. Ammonia Inhibition in Anaerobic Digestion: A Review. Process Biochemistry 2013, 48, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, M.J.; Everitt, T.; Villa, R. A Mass Transfer Model of Ammonia Volatilisation from Anaerobic Digestate. Waste Management 2010, 30, 1808–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Iyer, K.; Heaven, S.; Banks, C.J. Ammonia Removal in Anaerobic Digestion by Biogas Stripping: An Evaluation of Process Alternatives Using a First Order Rate Model Based on Experimental Findings. Chemical Engineering Journal 2011, 178, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Wernick, D.G.; Tat, C.A.; Liao, J.C. Consolidated Conversion of Protein Waste into Biofuels and Ammonia Using Bacillus Subtilis. Metabolic Engineering 2014, 23, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, Y.; Yoneda, H.; Tatsukami, Y.; Aoki, W.; Ueda, M. Ammonia Production from Amino Acid - Based Biomass - like Sources by Engineered Escherichia Coli. AMB Express 2017, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Aoki, W.; Ueda, M. Improved Ammonia Production from Soybean Residues by Cell Surface-Displayed l-Amino Acid Oxidase on Yeast. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 2021, 85, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatemichi, Y.; Kuroda, K.; Nakahara, T.; Ueda, M. Efficient Ammonia Production from Food by - Products by Engineered Escherichia Coli. AMB Express 2020, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, M. Establishment of Cell Surface Engineering and Its Development. Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry 2016, 80, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, K.; Ueda, M. Cell Surface Engineering of Yeast for Applications in White Biotechnology. Biotechnology letters 2011, 33, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Kuroda, K.; Tatemichi, Y.; Nakahara, T.; Aoki, W.; Ueda, M. Construction of Engineered Yeast Producing Ammonia from Glutamine and Soybean Residues ( Okara ). AMB Express 2020, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Ma, D.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, G.Q.; Deng, H.; Shi, Y. L-Glutamine Provides Acid Resistance for Escherichia Coli through Enzymatic Release of Ammonia. Cell Research 2013, 23, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloess, S.; Beuel, T.; Krüger, T.; Sewald, N.; Dierks, T.; Fischer von Mollard, G. Expression, Characterization, and Site-Specific Covalent Immobilization of an L-Amino Acid Oxidase from the Fungus Hebeloma Cylindrosporum. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2019, 103, 2229–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puniya, A.K.; Singh, R.; Kamra, D.N. Rumen Microbiology: From Evolution to Revolution. Rumen Microbiology: From Evolution to Revolution 2015, 1–379. [CrossRef]

- Eschenlauer, S.C.P.; McKain, N.; Walker, N.D.; McEwan, N.R.; Newbold, C.J.; Wallance, R.J. Ammonia Production by Ruminal Microorganisms and Enumeration, Isolation, and Characterization of Bacteria Capable of Growth on Peptides and Amino Acids from the Sheep Rumen. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2002, 68, 4925–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychlik, J.L.; Russell, J.B. Bacteriocin-Like Activity of Butyrivibrio Fibrisolvens JL5 and Its Effect on Other Ruminal Bacteria and Ammonia Production. Applied 2002, 68, 1040–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpeng, W.; Tan, Z. Ammonia Assimilation in Rumen Bacteria: A Review. Animal Biotechnology 2013, 24, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, A.; Calsamiglia, S.; Stern, M.D. Nitrogen Metabolism in the Rumen. Journal of dairy science 2005, 88, E9–E21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Soest, P.J. Nitrogen Metabolism. Nutritional ecology of the ruminant 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rychlik, J.L.; Lavera, R.; Russell, J.B. Amino Acid Deamination by Ruminal Megasphaera Elsdenii Strains. 2002, 45, 340–345. [CrossRef]

- Doelle, H.W. Nitrogen Metabolism as an Energy Source for Anaerobic Microorganisms (Clostridium). Bacterial Metabolism; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Strock, J.S. Nitrogen Cycle. 2008, 162–165.

- Nolan, J.V. Quantitative Models of Nitrogen Metabolism in Sheep. Digenstion and Metabolism in the Ruminant 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Valente, T.N.P.; da Silva Lima, E.; dos Santos, W.B.R.; Cesário, A.S.; Tavares, C.J.; de Freitas, M.A.M. Ruminal Microorganism Consideration and Protein Used in the Metabolism of the Ruminants: A Review. African Journal of Microbiology Research 2016, 10, 456–464. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraja, T.G. Microbiology of the Rumen. Rumenology 2016, 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, T.R.; Cotta, M.A. Isolation and Identification of Hyper-Ammonia Producing Bacteria from Swine Manure Storage Pits. Current Microbiology 2004, 48, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeniyi, A.; Bello, I.; Mukaila, T.; Hammed, A. A Review of Microbial Molecular Profiling during Biomass Valorization. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rychlik, J.L.; Russell, J.B. Mathematical Estimations of Hyper-Ammonia Producing Ruminal Bacteria and Evidence for Bacterial Antagonism That Decreases Ruminal Ammonia Production 1. 2000, 32, 121–128.

- Slyter, L.L. Influence of Acidosis on Rumen Function. Journal of animal science 1976, 43, 910–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Russell, J.B. More Monensin-Sensitive, Ammonia-Producing Bacteria from the Rumen. Applied and environmental microbiology 1989, 55, 1052–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, I.W. The Absorption of Ammonia from the Rumen of the Sheep. Biochemical Journal 1948, 42, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, M.P. The Characteristics of Strains of Selenomonas Isolated from Bovine Rumen Contents. Journal of Bacteriology 1956, 72, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, M.P.; Small, N. The Anaerobic Monotrichous Butyric Acid-Producing Curved Rod-Shaped Bacteria of the Rumen. Journal of Bacteriology 1956, 72, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, B.K.; Dufault, R.J.; Hassell, R.; Cutulle, M.A. Affinity of Hyperammonia-Producing Bacteria to Produce Bioammonium/Ammonia Utilizing Five Organic Nitrogen Substrates for Potential Use as an Organic Liquid Fertilizer. ACS omega 2018, 3, 11817–11822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M. Limiting Factors for the Enzymatic Accessibility of Soybean Protein; Wageningen University and Research, 2006.

- Sun, X.S. Bio-Based Polymers and Composites. In Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Soy Proteins; Elsevier Inc., 2005; pp. 292–326.

- Wang, L.; Liu, K.; Wang, Z.; Bai, X.; Peng, Q.; Jin, L. Bacterial Community Diversity Associated with Different Utilization Efficiencies of Nitrogen in the Gastrointestinal Tract of Goats. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, J.; Beal, J.D. Vegetable Protein Meals and the Effects of Enzymes. In Enzymes in farm animal nutrition; Bedford, M.R., Partridge, G.G., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2000; pp. 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, M.R. Exogenous Enzymes in Monogastric Nutrition - Their Current Value and Future Benefits. Animal Feed Science and Technology 2000, 86, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Sun, N.; Li, Y.; Cheng, S.; Lin, S. Targeted Regulation of Hygroscopicity of Soybean Antioxidant Pentapeptide Powder by Zinc Ions Binding to the Moisture Absorption Sites. Food Chemistry 2018, 242, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.; Huang, Y.; Islam, S.; Fan, B.; Tong, L.; Wang, F. Influence of the Degree of Hydrolysis on Functional Properties and Antioxidant Activity of Enzymatic Soybean Protein Hydrolysates. Molecules 2022, 27, 6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsman, G.J.P.; Gruppen, H.; Mul, A.J.; Voragen, A.G.J. In Vitro Accessibility of Untreated, Toasted, and Extruded Soybean Meals for Proteases and Carbohydrases. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1997, 45, 4088–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallés, J.P.; Huet, A.; Quillien, L.; Plumb, G.W.; Mills, E.N.C.; Morgen, M.R.A.; Toullec, R. Duodenal Passage of Immunoreactive Glycinin and B−conglycinin from Soya Bean in Preruminant Calves. In Recent advances of research in antinutritional factors in legume seeds and rapeseed; Jansman, A.J.M., Hill, G.D., Huisman, J., van der Poel, A.F.B., Eds.; Wageningen Press: Wageningen, 1998; pp. 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Merz, M.; Eisele, T.; Berends, P.; Appel, D.; Rabe, S.; Blank, I.; Stressler, T.; Fischer, L. Flavourzyme, an Enzyme Preparation with Industrial Relevance: Automated Nine-Step Purification and Partial Characterization of Eight Enzymes. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2015, 63, 5682–5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nchienzia, H.A.; Morawicki, R.O.; Gadang, V.P. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Poultry Meal with Endo- and Exopeptidases. Poultry Science 2010, 89, 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente, A.; Vioque, J.; Sánchez-Vioque, R.; Pedroche, J.; Bautista, J.; Millán, F. Protein Quality of Chickpea (Cicer Arietinum L.) Protein Hydrolysates. Food Chemistry 1999, 67, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, H.J.; In, M.J.; Kim, M.H. Process Development for the Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Food Protein: Effects of Pre-Treatment and Post-Treatments on Degree of Hydrolysis and Other Product Characteristics. Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering 1998, 3, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamnerdpetch, C.; Weiss, M.; Kasper, C.; Scheper, T. An Improvement of Potato Pulp Protein Hydrolyzation Process by the Combination of Protease Enzyme Systems. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 2007, 40, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nchienzia, H.A.; Morawicki, R.O.; Gadang, V.P. Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Poultry Meal with Endo- and Exopeptidases. Poultry Science 2010, 89, 2273–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunsakul, K.; Laokuldilok, T.; Sakdatorn, V.; Klangpetch, W.; Brennan, C.S.; Utama-ang, N. Optimization of Enzymatic Hydrolysis by Alcalase and Flavourzyme to Enhance the Antioxidant Properties of Jasmine Rice Bran Protein Hydrolysate. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Bu, G.; Chen, F. The Influence of Composite Enzymatic Hydrolysis on the Antigenicity of β-Conglycinin in Soy Protein Hydrolysates. Journal of Food Biochemistry 2018, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paster, B.J.; Russell, J.B.; Yang, C.M.J.; Chow, J.M.; Woese, C.R.; Tanner, R. Phylogeny of the Ammonia-Producing Ruminal Bacteria Peptostreptococcus Anaerobius, Clostridium Sticklandii, and Clostridium Aminophilum Sp. Nov. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 1993, 43, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balows, A.; Trüper, H.G.; Dworkin, M.; Harder, W.; Schleifer, K.-H. The Prokaryotes: A Handbook on the Biology of Bacteria: Ecophysiology, Isolation, Identification, Applications; Springer, 1992; Vol. 3;

- Gano, J.M. Amino Acid-Fermenting Bacteria from the Rumen of Dairy Cattle-Enrichment, Isolation, Characterization, and Interaction with Entodinium Caudatum. PhD Thesis, The Ohio State University, 2013.

- Chen, G.J.; Russell, J.B. Fermentation of Peptides and Amino Acids by a Monensin-Sensitive Ruminal Peptostreptococcus. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1988, 54, 2742–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attwood, G.T.; Klieve, A.V.; Ouwerkerk, D.; Patel, B.K.C. Ammonia-Hyperproducing Bacteria from New Zealand Ruminants. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1998, 64, 1796–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, C.J.; Wallace, R.J.; Eschenlauer, S.C.P.; Mckain, N.; Walker, N.D.; Mcewan, N.R.; Newbold, C.J. Ammonia Production by Ruminal Microorganisms and Enumeration, Isolation, and Characterization of Bacteria Capable of Growth on Peptides and Amino Acids from the Sheep Rumen Ammonia Production by Ruminal Microorganisms and Enumeration, Isolation, and C. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Kuiken, K.A.; Lyman, C.M.; Bradford, M.; Trant, M.; Dieterich, S. Essential Amino Acid Composition of Soy Bean Meals Prepared from Twenty Strains of Soy Beans. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1949, 177, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, I.; Adeniyi, A.; Mukaila, T.; Hammed, A. Optimization of Soybean Protein Extraction with Ammonium Hydroxide (NH4OH) Using Response Surface Methodology. Foods 2023, 12, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, T.R.; Cotta, M.A. Isolation and Identification of Hyper-Ammonia Producing Bacteria from Swine Manure Storage Pits. 2004, 48, 20–26.

- Attwood, G.T.; Klieve, A.V.; Ouwerkerk, D.; Patel, B.K. Ammonia-Hyperproducing Bacteria from New Zealand Ruminants. Applied and environmental microbiology 1998, 64, 1796–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bladen, H.A.; Bryant, M.P.; Doetsch, R.N. A Study of Bacterial Species from the Rumen Which Produce Ammonia from Protein Hydrolyzate. Applied Microbiology 1961, 9, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.J.; Russell, J.B. Effect of Monensin and a Protonophore on Protein Degradation, Peptide Accumulation, and Deamination by Mixed Ruminal Microorganisms in Vitro. Journal of Animal Science 1991, 69, 2196–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al, R.E.T. Effect of Carbohydrate Limitation on Degradation and Utilization of Casein by Mixed Rumen Bacteria. Journal of Dairy Science 1983, 66, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approach | Description | Host | Substrates | Ref |

| Gene knockout | Deletion of CodY gene which regulates genes:

|

Bacillus subtilis | Amino acid | [45]. |

| Gene knockout | Deletion of gene BkdB which helps in the biosynthesis of branched chain fatty acids | Bacillus subtilis | Amino acid | [45]. |

| Gene overexpression | Over expression of proteins leuDH, and two-keto-acid decarboxylase which respectively converts amino acids to important metabolic intermediates and increases the availability of metabolic precursors for ammonia production | Bacillus subtilis | Amino acid | [45]. |

| Gene knockout | Deletion of genes glnA and gdhA which aids ammonia assimilation | Eschericia coli | Amino acid | [46]. |

| Gene knockout | Deletion of ptsG (glucose transporter gene) and deletion of phosphoenol pyruvate (glucose transporter) | Eschericia coli | Soybean residue and food waste | [48] |

| Cell surface engineering | HcLAAO (L-amino acid oxidase) display on yeast cell surface by gene insertion | Yeast cells | Amino acids from soybean residue | [47] |

| Cell surface engineering | Glutaminase gene (Ybas) display on yeast cell surface by gene insertion. | Yeast cells | Soybean residue and glutamine | [51]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).