Submitted:

19 April 2023

Posted:

19 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Plant materials and growth conditions

2.2. Tissue section

2.3. Scanning electron microscopy

2.4. Quantification of cytokinins

2.5. RNA extraction, sequencing and analysis

2.6. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

2.7. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phenotype investigation of MS mutant

3.2. Abnormal development of the SAM in MS mutant

3.3. CK levels are elevated in the SAM of the MS mutant

3.4. RNA-seq analysis of the SAM in MS mutant

3.5. Differential transcriptional in different developmental stages in the SAM of MS mutant

3.6. GO and KEGG analysis of all DEGs

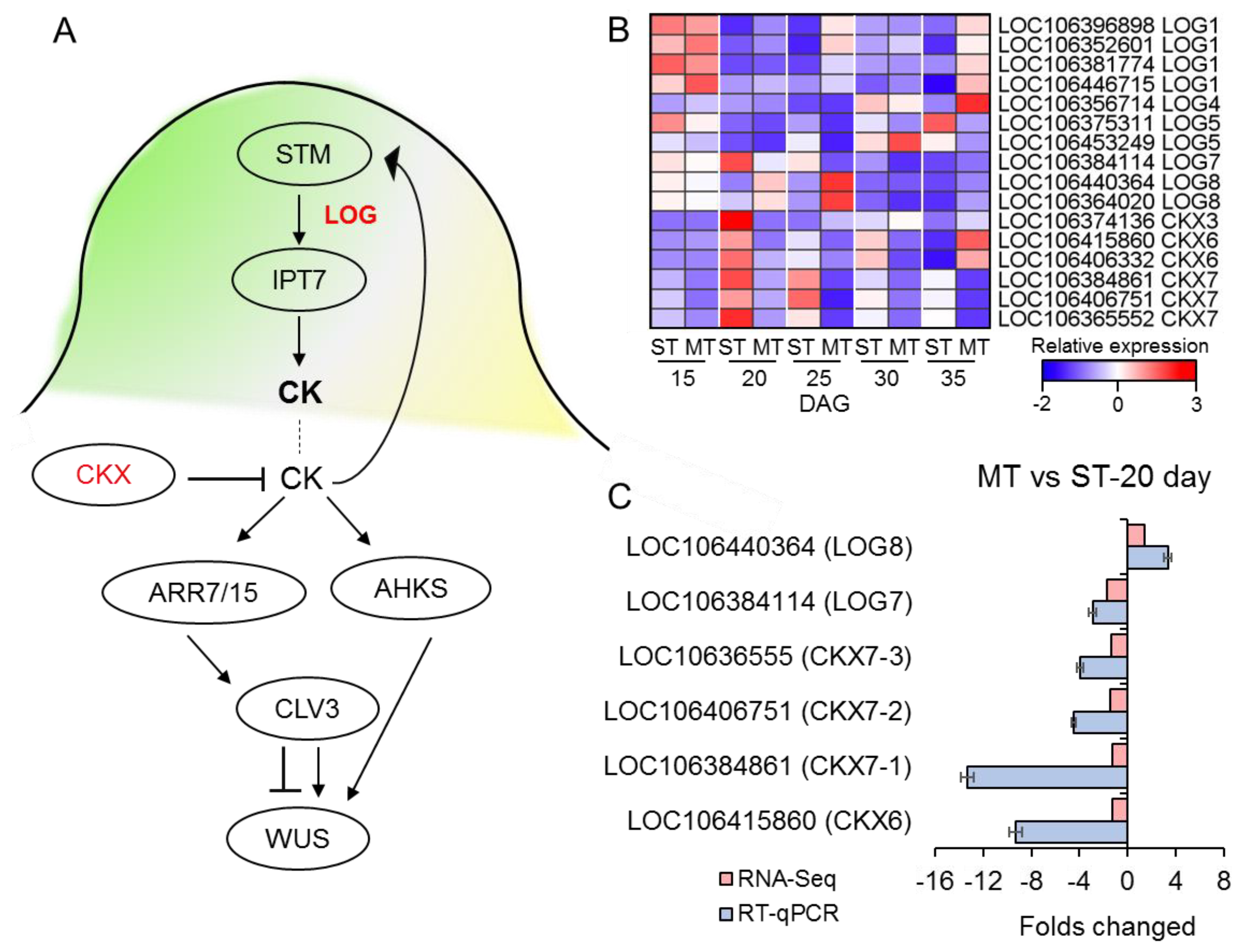

3.7. The expression of CK-related genes was affected in the SAM of MS mutant

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mänd M., Williams I.H., Viik E., Karise R.: Oilseed rape, bees and integrated pest management. In: Biocontrol-Based Integrated Management of Oilseed Rape Pests. Edited by Williams IH. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2010: 357-379.

- Raboanatahiry N., Li H., Yu L., Li M.: Rapeseed (Brassica napus): Processing, Utilization, and Genetic Improvement. In: Agronomy. vol. 11; 2021.

- Shimizu-Sato, S.; Mori, H. Shimizu-Sato, S.; Mori, H. Control of outgrowth and dormancy in axillary buds. Plant physiology 2001, 127, 1405–1413.

- McSteen, P.; Leyser, O. McSteen, P.; Leyser, O. Shoot branching. Annual review of plant biology 2005, 56, 353–374. [CrossRef]

- Aichinger, E.; Kornet, N.; Friedrich, T.; Laux, T. Aichinger, E.; Kornet, N.; Friedrich, T.; Laux, T. Plant stem cell niches. Annual review of plant biology 2012, 63, 615–636. [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.K. Barton, M.K. Twenty years on: the inner workings of the shoot apical meristem, a developmental dynamo. Dev Biol 2010, 341, 95–113. [CrossRef]

- Barbier, F.F.; Dun, E.A.; Kerr, S.C.; Chabikwa, T.G.; Beveridge, C.A. Barbier, F.F.; Dun, E.A.; Kerr, S.C.; Chabikwa, T.G.; Beveridge, C.A. An Update on the Signals Controlling Shoot Branching. Trends Plant Sci 2019, 24, 220–236. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Smith, S.M.; Li, J. Wang, B.; Smith, S.M.; Li, J. Genetic Regulation of Shoot Architecture. Annual review of plant biology 2018, 69, 437–468. [CrossRef]

- Shani, E.; Yanai, O.; Ori, N. Shani, E.; Yanai, O.; Ori, N. The role of hormones in shoot apical meristem function. Current opinion in plant biology 2006, 9, 484–489. [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, H. Sakakibara, H. Cytokinins: activity, biosynthesis, and translocation. Annual review of plant biology 2006, 57, 431–449. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, C.; Ohashi, Y.; Sato, S.; Kato, T.; Tabata, S.; Ueguchi, C. Nishimura, C.; Ohashi, Y.; Sato, S.; Kato, T.; Tabata, S.; Ueguchi, C. Histidine kinase homologs that act as cytokinin receptors possess overlapping functions in the regulation of shoot and root growth in Arabidopsis. The Plant cell 2004, 16, 1365–1377. [CrossRef]

- Tantikanjana, T.; Yong, J.W.; Letham, D.S.; Griffith, M.; Hussain, M.; Ljung, K.; Sandberg, G.; Sundaresan, V. Tantikanjana, T.; Yong, J.W.; Letham, D.S.; Griffith, M.; Hussain, M.; Ljung, K.; Sandberg, G.; Sundaresan, V. Control of axillary bud initiation and shoot architecture in Arabidopsis through the SUPERSHOOT gene. Genes & development 2001, 15, 1577–1588. [CrossRef]

- Giulini, A.; Wang, J.; Jackson, D. Giulini, A.; Wang, J.; Jackson, D. Control of phyllotaxy by the cytokinin-inducible response regulator homologue ABPHYL1. Nature 2004, 430, 1031–1034. [CrossRef]

- Werner, T.; Köllmer, I.; Bartrina, I.; Holst, K.; Schmülling, T. Werner, T.; Köllmer, I.; Bartrina, I.; Holst, K.; Schmülling, T. New insights into the biology of cytokinin degradation. Plant biology (Stuttgart, Germany) 2006, 8, 371–381. [CrossRef]

- Werner, T.; Motyka, V.; Laucou, V.; Smets, R.; Van Onckelen, H.; Schmülling, T. Werner, T.; Motyka, V.; Laucou, V.; Smets, R.; Van Onckelen, H.; Schmülling, T. Cytokinin-deficient transgenic Arabidopsis plants show multiple developmental alterations indicating opposite functions of cytokinins in the regulation of shoot and root meristem activity. The Plant cell 2003, 15, 2532–2550. [CrossRef]

- Motyka, V.; Faiss, M.; Strand, M.; Kaminek, M.; Schmulling, T. Motyka, V.; Faiss, M.; Strand, M.; Kaminek, M.; Schmulling, T. Changes in Cytokinin Content and Cytokinin Oxidase Activity in Response to Derepression of ipt Gene Transcription in Transgenic Tobacco Calli and Plants. Plant physiology 1996, 112, 1035–1043. [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.O.; Bilyeu, K.D.; Laskey, J.G.; Cheikh, N.N. Morris, R.O.; Bilyeu, K.D.; Laskey, J.G.; Cheikh, N.N. Isolation of a gene encoding a glycosylated cytokinin oxidase from maize. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 1999, 255, 328–333. [CrossRef]

- Ashikari, M.; Sakakibara, H.; Lin, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Takashi, T.; Nishimura, A.; Angeles, E.R.; Qian, Q.; Kitano, H.; Matsuoka, M. Ashikari, M.; Sakakibara, H.; Lin, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Takashi, T.; Nishimura, A.; Angeles, E.R.; Qian, Q.; Kitano, H.; Matsuoka, M. Cytokinin oxidase regulates rice grain production. Science 2005, 309, 741–745. [CrossRef]

- Mameaux, S.; Cockram, J.; Thiel, T.; Steuernagel, B.; Stein, N.; Taudien, S.; Jack, P.; Werner, P.; Gray, J.C.; Greenland, A.J.; et al. Mameaux, S.; Cockram, J.; Thiel, T.; Steuernagel, B.; Stein, N.; Taudien, S.; Jack, P.; Werner, P.; Gray, J.C.; Greenland, A.J.; et al. Molecular, phylogenetic and comparative genomic analysis of the cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase gene family in the Poaceae. Plant Biotechnol J 2012, 10, 67–82. [CrossRef]

- Le, D.T.; Nishiyama, R.; Watanabe, Y.; Vankova, R.; Tanaka, M.; Seki, M.; Ham le, H.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Tran, L.S. Le, D.T.; Nishiyama, R.; Watanabe, Y.; Vankova, R.; Tanaka, M.; Seki, M.; Ham le, H.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Tran, L.S. Identification and expression analysis of cytokinin metabolic genes in soybean under normal and drought conditions in relation to cytokinin levels. PLoS One 2012, 7, e42411. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, C.; Ma, J.Q.; Zhang, L.Y.; Yang, B.; Tang, X.Y.; Huang, L.; Zhou, X.T.; Lu, K.; Li, J.N. Liu, P.; Zhang, C.; Ma, J.Q.; Zhang, L.Y.; Yang, B.; Tang, X.Y.; Huang, L.; Zhou, X.T.; Lu, K.; Li, J.N. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Profiling of Cytokinin Oxidase/Dehydrogenase (CKX) Genes Reveal Likely Roles in Pod Development and Stress Responses in Oilseed Rape (Brassica napus L.). Genes (Basel) 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Kurakawa, T.; Ueda, N.; Maekawa, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Kojima, M.; Nagato, Y.; Sakakibara, H.; Kyozuka, J. Kurakawa, T.; Ueda, N.; Maekawa, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Kojima, M.; Nagato, Y.; Sakakibara, H.; Kyozuka, J. Direct control of shoot meristem activity by a cytokinin-activating enzyme. Nature 2007, 445, 652–655. [CrossRef]

- Kuroha, T.; Tokunaga, H.; Kojima, M.; Ueda, N.; Ishida, T.; Nagawa, S.; Fukuda, H.; Sugimoto, K.; Sakakibara, H. Kuroha, T.; Tokunaga, H.; Kojima, M.; Ueda, N.; Ishida, T.; Nagawa, S.; Fukuda, H.; Sugimoto, K.; Sakakibara, H. Functional analyses of LONELY GUY cytokinin-activating enzymes reveal the importance of the direct activation pathway in Arabidopsis. The Plant cell 2009, 21, 3152–3169. [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, H.; Kojima, M.; Kuroha, T.; Ishida, T.; Sugimoto, K.; Kiba, T.; Sakakibara, H. Tokunaga, H.; Kojima, M.; Kuroha, T.; Ishida, T.; Sugimoto, K.; Kiba, T.; Sakakibara, H. Arabidopsis lonely guy (LOG) multiple mutants reveal a central role of the LOG-dependent pathway in cytokinin activation. The Plant journal : for cell and molecular biology 2012, 69, 355–365. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Shao, G.; Xiong, J.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, G.; Meng, X.; Liang, Y.; Xiong, G.; Wang, Y.; et al. Lu, Z.; Shao, G.; Xiong, J.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, G.; Meng, X.; Liang, Y.; Xiong, G.; Wang, Y.; et al. MONOCULM 3, an ortholog of WUSCHEL in rice, is required for tiller bud formation. Journal of genetics and genomics = Yi chuan xue bao 2015, 42, 71–78. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.S.; Ren, T.H.; Li, Z.; Tang, Y.Z.; Ren, Z.L.; Yan, B.J. Hu, Y.S.; Ren, T.H.; Li, Z.; Tang, Y.Z.; Ren, Z.L.; Yan, B.J. Molecular mapping and genetic analysis of a QTL controlling spike formation rate and tiller number in wheat. Gene 2017, 634, 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chao, H.; Zhang, L.; Ta, N.; Zhao, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, K.; Guan, Z.; Hou, D.; Chen, K.; et al. Zhao, W.; Chao, H.; Zhang, L.; Ta, N.; Zhao, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, K.; Guan, Z.; Hou, D.; Chen, K.; et al. Integration of QTL Mapping and Gene Fishing Techniques to Dissect the Multi-Main Stem Trait in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Front Plant Sci 2019, 10, 1152. [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Wei, C. Xu, A.; Wei, C. Comprehensive comparison and applications of different sections in investigating the microstructure and histochemistry of cereal kernels. Plant methods 2020, 16, 8. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Ebrahimpour, P.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Alonso, L.C. Kong, Y.; Ebrahimpour, P.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Alonso, L.C. Pancreatic Islet Embedding for Paraffin Sections. J Vis Exp 2018, 10.3791/57931. [CrossRef]

- Tarkowski, P.; Ge, L.; Yong, J.W.H.; Tan, S.N. Tarkowski, P.; Ge, L.; Yong, J.W.H.; Tan, S.N. Analytical methods for cytokinins. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2009, 28, 323–335. [CrossRef]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.H.; Xia, R. Chen, C.J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.H.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Molecular Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods (San Diego, Calif.) 2001, 25, 402–408. [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Vernoux, T. Shi, B.; Vernoux, T. Hormonal control of cell identity and growth in the shoot apical meristem. Current opinion in plant biology 2022, 65, 102111. [CrossRef]

- Skylar, A.; Wu, X. Skylar, A.; Wu, X. Regulation of meristem size by cytokinin signaling. Journal of integrative plant biology 2011, 53, 446–454. [CrossRef]

- Skoog, F.; Thimann, K.V. Skoog, F.; Thimann, K.V. Further Experiments on the Inhibition of the Development of Lateral Buds by Growth Hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1934, 20, 480–485. [CrossRef]

- Stirnberg, P.; van De Sande, K.; Leyser, H.M. Stirnberg, P.; van De Sande, K.; Leyser, H.M. MAX1 and MAX2 control shoot lateral branching in Arabidopsis. Development 2002, 129, 1131–1141. [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhai, W.; Pan, X.; Zhu, L. Zou, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, G.; Zhao, X.; Zhai, W.; Pan, X.; Zhu, L. Characterizations and fine mapping of a mutant gene for high tillering and dwarf in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Planta 2005, 222, 604–612. [CrossRef]

- Beveridge, C.A. Beveridge, C.A. Long-distance signalling and a mutational analysis of branching in pea. Plant Growth Regulation 2000, 32, 193–203. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Roldan, V.; Fermas, S.; Brewer, P.B.; Puech-Pages, V.; Dun, E.A.; Pillot, J.P.; Letisse, F.; Matusova, R.; Danoun, S.; Portais, J.C.; et al. Gomez-Roldan, V.; Fermas, S.; Brewer, P.B.; Puech-Pages, V.; Dun, E.A.; Pillot, J.P.; Letisse, F.; Matusova, R.; Danoun, S.; Portais, J.C.; et al. Strigolactone inhibition of shoot branching. Nature 2008, 455, 189–194. [CrossRef]

- Hayward, A.; Stirnberg, P.; Beveridge, C.; Leyser, O. Hayward, A.; Stirnberg, P.; Beveridge, C.; Leyser, O. Interactions between auxin and strigolactone in shoot branching control. Plant physiology 2009, 151, 400–412. [CrossRef]

- Domagalska, M.A.; Leyser, O. Domagalska, M.A.; Leyser, O. Signal integration in the control of shoot branching. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology 2011, 12, 211–221. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, S.P.; Chickarmane, V.S.; Ohno, C.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Gordon, S.P.; Chickarmane, V.S.; Ohno, C.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Multiple feedback loops through cytokinin signaling control stem cell number within the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 16529–16534. [CrossRef]

- Salam, B.B.; Malka, S.K.; Zhu, X.; Gong, H.; Ziv, C.; Teper-Bamnolker, P.; Ori, N.; Jiang, J.; Eshel, D. Salam, B.B.; Malka, S.K.; Zhu, X.; Gong, H.; Ziv, C.; Teper-Bamnolker, P.; Ori, N.; Jiang, J.; Eshel, D. Etiolated Stem Branching Is a Result of Systemic Signaling Associated with Sucrose Level. Plant physiology 2017, 175, 734–745. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Bai, X.; Zhang, C.; He, Y. Xiao, Q.; Bai, X.; Zhang, C.; He, Y. Advanced high-throughput plant phenotyping techniques for genome-wide association studies: A review. J Adv Res 2022, 35, 215–230. [CrossRef]

- Brachi, B.; Morris, G.P.; Borevitz, J.O. Brachi, B.; Morris, G.P.; Borevitz, J.O. Genome-wide association studies in plants: the missing heritability is in the field. Genome biology 2011, 12, 232. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Saeed, S.; Khan, M.H.U.; Fan, C.; Ahmar, S.; Arriagada, O.; Shahzad, R.; Branca, F.; Mora-Poblete, F. Khan, S.U.; Saeed, S.; Khan, M.H.U.; Fan, C.; Ahmar, S.; Arriagada, O.; Shahzad, R.; Branca, F.; Mora-Poblete, F. Advances and Challenges for QTL Analysis and GWAS in the Plant-Breeding of High-Yielding: A Focus on Rapeseed. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Liu, J.; Hua, W.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Sun, F.; Liu, J.; Hua, W.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Identification of stable QTLs for seed oil content by combined linkage and association mapping in Brassica napus. Plant Sci 2016, 252, 388–399. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wei, L.; Wang, J.; Xie, L.; Li, Y.Y.; Ran, S.; Ren, L.; Lu, K.; Li, J.; Timko, M.P.; et al. Wang, T.; Wei, L.; Wang, J.; Xie, L.; Li, Y.Y.; Ran, S.; Ren, L.; Lu, K.; Li, J.; Timko, M.P.; et al. Integrating GWAS, linkage mapping and gene expression analyses reveals the genetic control of growth period traits in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Biotechnol Biofuels 2020, 13, 134. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Xie, M.; Liang, L.; Yang, L.; Han, H.; Qin, X.; Zhao, J.; Hou, Y.; Dai, W.; Du, C.; et al. Zhao, C.; Xie, M.; Liang, L.; Yang, L.; Han, H.; Qin, X.; Zhao, J.; Hou, Y.; Dai, W.; Du, C.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Analysis Combined With Quantitative Trait Loci Mapping and Dynamic Transcriptome Unveil the Genetic Control of Seed Oil Content in Brassica napus L. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 929197. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, T.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Fu, T.; Meng, J.; Tu, J.; Ma, C.J.C. Li, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, T.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Fu, T.; Meng, J.; Tu, J.; Ma, C.J.C. QTL analysis of yield-related traits and their association with functional markers in Brassica napus L. Crop and Pasture Science 2007, 58, 759–766.

- Shi, J.; Li, R.; Qiu, D.; Jiang, C.; Long, Y.; Morgan, C.; Bancroft, I.; Zhao, J.; Meng, J. Shi, J.; Li, R.; Qiu, D.; Jiang, C.; Long, Y.; Morgan, C.; Bancroft, I.; Zhao, J.; Meng, J. Unraveling the complex trait of crop yield with quantitative trait loci mapping in Brassica napus. Genetics 2009, 182, 851–861. [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Zhao, Z.; Liao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Shi, L.; Long, Y.; Xu, F. Ding, G.; Zhao, Z.; Liao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Shi, L.; Long, Y.; Xu, F. Quantitative trait loci for seed yield and yield-related traits, and their responses to reduced phosphorus supply in Brassica napus. Annals of botany 2012, 109, 747–759. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, B.; Tu, J.; Tingdong, F. Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, B.; Tu, J.; Tingdong, F. Detection of QTL for six yield-related traits in oilseed rape (Brassica napus) using DH and immortalized F(2) populations. TAG. Theoretical and applied genetics. Theoretische und angewandte Genetik 2007, 115, 849–858. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Ma, C.; Yue, Y.; Hu, K.; Li, Y.; Duan, Z.; Wu, M.; Tu, J.; Shen, J.; Yi, B.; et al. Luo, X.; Ma, C.; Yue, Y.; Hu, K.; Li, Y.; Duan, Z.; Wu, M.; Tu, J.; Shen, J.; Yi, B.; et al. Unravelling the complex trait of harvest index in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) with association mapping. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 379. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Chen, B.; Xu, K.; Gao, G.; Yan, G.; Qiao, J.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Xiao, X.; et al. Li, F.; Chen, B.; Xu, K.; Gao, G.; Yan, G.; Qiao, J.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Xiao, X.; et al. A genome-wide association study of plant height and primary branch number in rapeseed (Brassica napus). Plant Sci 2016, 242, 169–177. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wu, D.; Wei, D.; Fu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Dong, H.; Tan, C.; Qian, W. He, Y.; Wu, D.; Wei, D.; Fu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Dong, H.; Tan, C.; Qian, W. GWAS, QTL mapping and gene expression analyses in Brassica napus reveal genetic control of branching morphogenesis. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 15971. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Peng, C.; Liu, H.; Tang, M.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; et al. Zheng, M.; Peng, C.; Liu, H.; Tang, M.; Yang, H.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals Candidate Genes for Control of Plant Height, Branch Initiation Height and Branch Number in Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Front Plant Sci 2017, 8, 1246. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Gao, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Shen, W.; Yi, B.; Wen, J.; Ma, C.; Shen, J.; Fu, T.; et al. Li, B.; Gao, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Shen, W.; Yi, B.; Wen, J.; Ma, C.; Shen, J.; Fu, T.; et al. Identification and fine mapping of a major locus controlling branching in Brassica napus. TAG. Theoretical and applied genetics. Theoretische und angewandte Genetik 2020, 133, 771–783. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Su, T.; Zhang, B.; Li, P.; Xin, X.; Yue, X.; Cao, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Yu, Y.; et al. Li, P.; Su, T.; Zhang, B.; Li, P.; Xin, X.; Yue, X.; Cao, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Yu, Y.; et al. Identification and fine mapping of qSB.A09, a major QTL that controls shoot branching in Brassica rapa ssp. chinensis Makino. TAG. Theoretical and applied genetics. Theoretische und angewandte Genetik 2020, 133, 1055–1068. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).