Submitted:

19 April 2023

Posted:

20 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. General and historical profiles

1.2. Clinical profiles

1.3. Aim

- Is it possible to distinguish one or more forms of hypersexuality? And if so, is there a pathological form and how does it differ from the other hypotheses?

- Is it possible to say that pathological hypersexuality is a clinical condition, medically relevant, or is it a subjective maladaptive behaviour? And if it is a condition, is it primary or secondary?

- Is it possible to identify the aetiology of pathological hypersexuality with scientific certainty, thus in a reproducible and agreeable manner?

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Review Questions

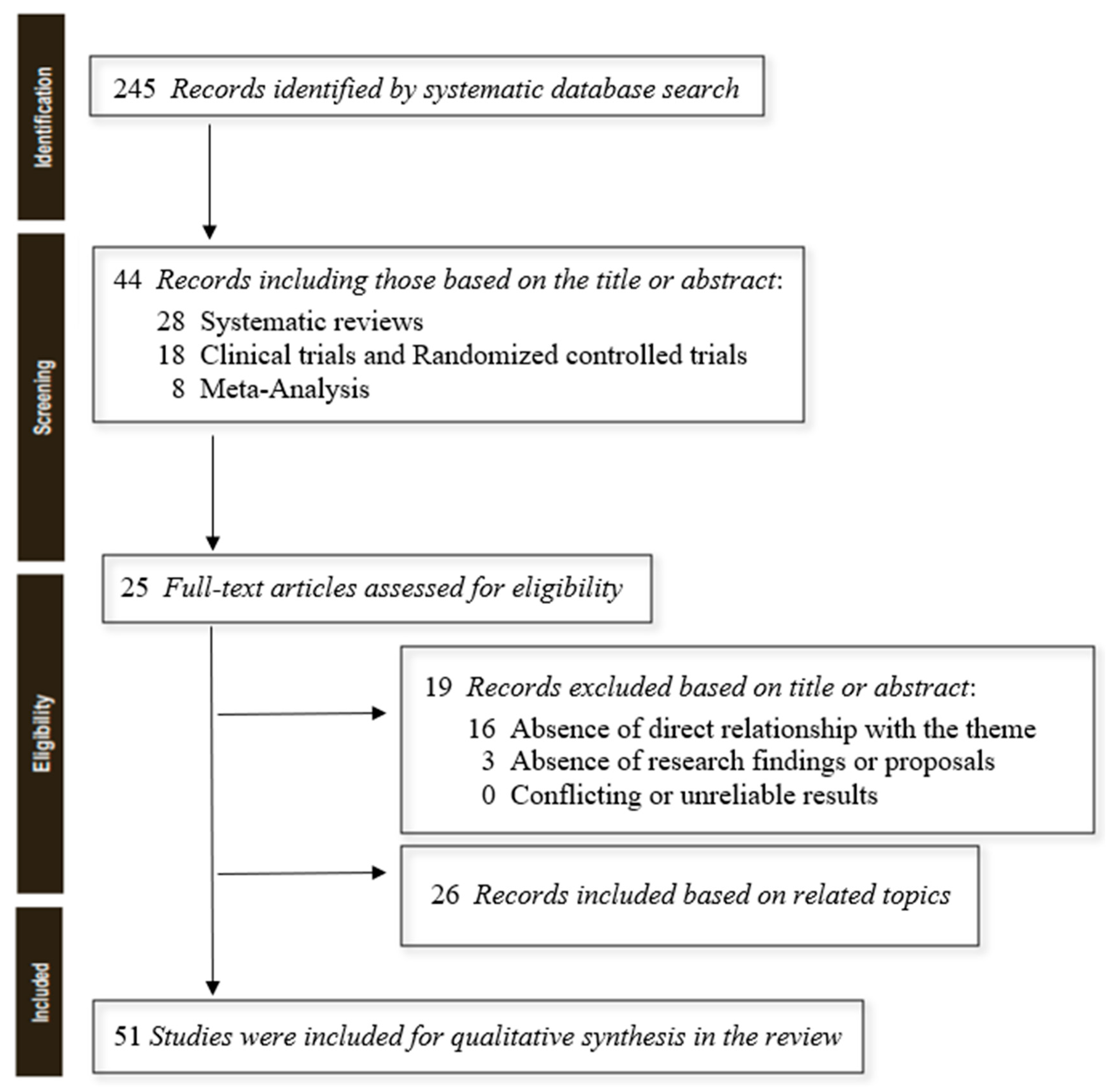

2.3. Materials and methods

3. Results

3.1. The different forms of hypersexuality

3.2. Hypersexuality as a clinical condition or maladaptive behaviour?

3.3. The etiopathological theories of hypersexuality

| Theoretical models | Content |

|---|---|

| Compulsive | Hypersexuality is a modality of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), in that they would manifest as recurrent and intense sexual fantasies that interfere with the performance of normal daily activities, while compulsions could be configured as sexual behaviours that are very difficult to counteract and take up a lot of the person's available time. In addition, the sexual act (whether masturbatory or through intercourse with a partner) is seen as a libidinal drive release mechanism that increases concerning times of high stress. However, unlike OCD, thoughts and behaviours related to sexuality are egosyntonic, i.e., consistent with one's self; they do not create discomfort for the person and are seen as natural and devoid of any problematic aspects, on par with personality disorders. Those suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder, on the other hand, perceive obsessions as highly intrusive. Hypersexuality cannot, therefore, be part of the category of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, strictly speaking. |

| Impulsive | The impulsive dysfunctional model is the one deemed correct by the World Health Organization, in which hypersexuality is seen as an impulse control disorder. Underlying it is the idea that the hypersexual person is unable to adequately manage his or her sexual impulses: he or she would act on them, without modulating them, the moment he or she feels them. This presupposes a sexual tension that cannot be procrastinated before the act and its release during the act, which would be followed by guilt. The lack of inhibition is due to frontal lobe malfunction. This position, however, clashes with the behavioural representation of the hypersexual subject who is anything but impulsive in organizational acting out: although the impulse may be correctly labelled as irrepressible, in most cases the subject then comes to plan his or her activities in a lucid, rational and methodical manner. |

| Additional (neurobiology) | The addiction model attempts to explain hypersexuality as a behavioral addiction because of the peculiar characteristics common to addictions precisely: the tendency to tolerate sexual activity (sexual intercourse is less and less satisfying); the occurrence of withdrawal symptoms in the absence of sexual activity, such as rumination, anxiety and guilt; the difficulty in reducing, or otherwise controlling, sexual behaviors (such as compulsive masturbation, heavy use of pornography, seeking sexual stimulation through the Internet and social networks, cybersex practices, promiscuous, multiple and/or casual sexuality, disinterest in the risk of contracting diseases through unprotected sexual conduct, prostitution, need for infidelity); the use of more and more considerable time aimed at seeking partners; the reduction of time devoted to other activities (sociality disappears in favor of sexual activity); the act is perpetrated despite the fact that it entails negative consequences more or less impacting the subject's personal and social life. Moreover, this model finds particular reinforcement from scientific evidence, which has been derived from studies of the neurophysiological correlates of hypersexuality. Neuroimaging techniques have revealed dysfunction in the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems, frameworks typical of addictions, precisely underlying the compulsive and uncontrolled pursuit of sexual satisfaction. The dopamine neurotransmitter emitted by neurons located in the limbic system (nucleus accumbens) would be released in a dysregulated manner in individuals with hypersexuality, due to an exaggerated and disproportionate overactivity of the Mesolimbic-dopaminergic and nigrostriatal pathways. In individuals with impulse dysregulation disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder, it is precisely this function that would be affected. Although not yet definitively validated by significant scientific research, scholars have also theorized the involvement in the aetiology of hypersexuality of the neurotransmitter serotonergic, a neuronal hormone that makes people experience the feeling of happiness, satiety and fulfilment. The same reasoning must also be applied to oxytocin [41], which is directly involved in social and affective relationships. |

| Psychodramatic | It distinguishes the disorder of hypersexuality from normal intense sexual activity, citing traumatic reasons behind the establishment of dysfunctional behaviour. Psychometric instruments are used to shareable label the clinical response. [1,39,40,42] |

| Questions | Answers |

|---|---|

| Is it possible to distinguish one or more forms of hypersexuality? And if so, is there a pathological form and how does it differ from the other hypotheses? | Currently, it is not possible in the literature to distinguish between the different forms of hypersexuality, except by trying to identify the form deemed pathological because it meets the diagnostic criteria proposed by ICD-11. For this reason, the Perrotta Hypersexuality Scale (PHS-1) was suggested. |

| Is it possible to say that pathological hypersexuality is a clinical condition, medically relevant, or is it a subjective maladaptive behaviour? And if it is a condition, is it primary or secondary? | Hypersexuality is a potentially clinically relevant condition, secondary to another medical condition (encephalic trauma, neurological, drugs, substance abuse, and psychiatric) and consisting of one or more dysfunctional and pathological behaviours of one's sexual sphere. |

| Is it possible to identify the aetiology of pathological hypersexuality with scientific certainty, thus in a reproducible and agreeable manner? | Several etiopathological theories in the literature try to explain hypersexuality, but all of them do not seem to be fully satisfactory enough to answer the question in a supportable and reproducible way. However, if the compulsive, impulsive, and psycho-traumatic models can partially explain the hypersexual condition, the neurobiological model manages to be more precise. |

| Author (Year) | Objectives | Type | Key Results and Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Montgomery-Graham, S. (2017) | Conceptualization and Assessment of Hypersexual Disorder | R | The Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory, the measures proposed for the clinical screening of HD by the DSM-5 workgroup, currently has the strongest psychometric support. |

| Parra-Dìaz, P. et al. (2020) | Impulse control disorders (ICDs) and Parkinson's disease (PD) | R | The tendency towards a different ICD profile in different geographical areas may be attributable to socio-economical, cultural or political influences in the phenomenology of these disorders. |

| Soldati, L. et al. (2020) | Sexual Function/Dysfunctions and ADHD | M | ADHD is a mental disorder affecting sexual health. Further studies are warranted to learn more about sexuality in subjects with ADHD. |

| Korchia, T. et al. (2022) | ADHD prevalence in patients with hypersexuality and paraphilic disorders | M | ADHD is much more frequent in populations with hypersexuality or paraphilic disorders compared to the general population. |

| Latella, D. et al. (2021) | Hypersexuality in neurological diseases | M | Hypersexuality is a frequent sexual disorder in patients with neurological disorders, especially neurodegenerative ones. |

| Codling, D. et al. (2015) | Hypersexuality in Parkinson's Disease | R | A brief survey of the neurobiology of sexuality, suggests possible avenues for further research and treatment of HS. |

| Nakum, S., Cavanna, A.E. (2016) | Hypersexuality in Parkinson's Disease | R | Hypersexuality is not rare in patients with PD treated with DRT, particularly in those on dopamine agonists. |

| de Oliveira, M. et al. (2013) | Pharmacological treatment for Kleine-Levin syndrome | R | Therapeutic trials of pharmacological treatment for Kleine-Levin syndrome with a double-blind, placebo-controlled design are needed. |

| Burley, C.V. et al. (2022) | Pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches and dementia | R | Pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches to reduce disinhibited behaviours in dementia |

| de Alarcòn, R. et al. (2019) | Online Porn Addiction | R | Hypersexual disorder fits this model and may be composed of several sexual behaviours, like problematic use of online pornography (POPU). |

| Karila, L. et al. (2014) | Sexual addiction or hypersexual disorder | R | Addictive, somatic and psychiatric disorders coexist with sexual addiction. |

| Castellini, G. et al. (2016) | Sexuality in eating disorders patients | R | The analysis of the literature showed an association between sexual orientation and gender dysphoria with EDs psychopathology and pathological eating behaviours, confirming the validity of research developing new models of maintaining factors of EDs related to the topic of self-identity. |

| Kowatch, R.A. et al. (2005) | Phenomenology and clinical characteristics of mania in children and adolescents | M | The clinical picture that emerges is that of children or adolescents with periods of increased energy (mania or hypomania), accompanied by distractibility, pressured speech, irritability, grandiosity, racing thoughts, decreased need for sleep and euphoria/elation. |

| de Oliveira, L. et al. (2020) | The Link Between Boredom and Hypersexuality | R | Although current literature identifies a link between boredom and hypersexuality, further substantive research is still much needed to clarify the associations between the 2 constructs. |

| Schultz, K. et al. (2014) | Nonparaphilic Hypersexual Behavior and Depressive Symptoms | M | There was a moderate, positive relation between non-paraphilic hypersexual behaviour and depressive symptoms. This relation was similar across gender, sexual orientation, and age. |

| Jennings, T.L. (2021) | Compulsive sexual behaviour, religiosity, and spirituality | R | Although research examining CSB and religiosity has flourished, such growth is hampered by cross-sectional samples lacking in diversity. Moral incongruence assists in explaining the relationship between religiosity and PPU, but future research should consider other manifestations of CSB beyond PPU. |

| Landgren, V. (2022) | Effects of testosterone suppression on desire, hypersexuality, and sexual interest in children in men with pedophilic disorder | RES | The effects of testosterone withdrawal on significant correlates of paedophilic disorder (PeD) are largely unknown. The purpose of this study was to explore in detail the effects of testosterone suppression from degarelix as compared to placebo on desire, hypersexuality, and subjectively experienced sexual interest in participants with PeD. We compared the sexual effects of degarelix, a GnRH antagonist, on men with PeD assigned to degarelix or placebo. Sexual Desire Inventory scores decreased significantly at two weeks and ten weeks in participants assigned degarelix, whereas HBI ratings did not differ significantly at two weeks, but did so at ten weeks. 15 out of 26 individuals (58%) in the group given degarelix and 3 out of 26 (12%) in the group given the placebo reported no further sexual interest in children, at ten weeks. |

| Walton, M.T. (2017) | Hypersexuality | R | Our discussion of hypersexuality covers a diversity of research and clinical perspectives. |

| Hallberg, J. (2017) | A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Group Intervention for Hypersexual Disorder | RES | Although participants reported decreased HD symptoms after attending the CBT program, future studies should evaluate the treatment program with a larger sample and a randomized controlled procedure to ensure treatment effectiveness. |

| Hallberg, J. (2017) | A Randomized Controlled Study of Group-Administered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Hypersexual Disorder in Men | RES | A significantly greater decrease in HD symptoms and sexual compulsivity, as well as significantly greater improvements in psychiatric well-being, were found for the treatment condition compared with the waitlist. These effects remained stable at 3 and 6 months after treatment. |

| Schecklmann, M. (2020) | Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation as a Potential Tool to Reduce Sexual Arousal | RES | The results indicate that 1 session of high-frequency rTMS (10 Hz) of the right DLPFC could significantly reduce subjective sexual arousal induced by visual stimuli in healthy subjects. |

| Chatzittofis, A. (2016) | HPA axis dysregulation in men with hypersexual disorder | RES | Hypersexual disorder integrating pathophysiological aspects such as sexual desire deregulation, sexual addiction, impulsivity and compulsivity was suggested as a diagnosis for the DSM-5. The patients reported significantly more childhood trauma and depression symptoms compared to healthy volunteers. The diagnosis of hypersexual disorder was significantly associated with DST non-suppression and higher plasma DST-ACTH even when adjusted for childhood trauma. The results suggest HPA axis dysregulation in male patients with hypersexual disorder |

| Oei, N.Y.L. et al. (2012) | Dopamine modulates reward system activity during the subconscious processing of sexual stimuli | RES | Brain activation was assessed during a backwards-masking task with subliminally presented sexual stimuli. Results showed that levodopa significantly enhanced the activation in the nucleus accumbens and dorsal anterior cingulate when subliminal sexual stimuli were shown, whereas haloperidol decreased activations in those areas. Dopamine thus enhances activations in regions thought to regulate 'wanting' in response to potentially rewarding sexual stimuli that are not consciously perceived. This running start of the reward system might explain the pull of rewards in individuals with compulsive reward-seeking behaviours such as hypersexuality and patients who receive dopaminergic medication |

4. Discussion and limitations

| High-functioning pathological | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Colour | Definition | Behaviour |

| 1 | Pink | Pro-active hypersexuality | The subject presents an accentuation of the sexual storyline, in terms of drive needs that are higher than the statistical average of the reference population but still fall within the physiological framework or subjective normality because they do not respond to any existing nosographic pathological profile. He or she can moderate his or her behaviour and adapt to the social context, despite feeling a reasonably more significant drive present than expected, due to age and individual and collective relational context. The fulfilment of these needs is embodied in a greater drive to seek and achieve them, but no dysfunctional conduct, relevant paraphiliac comorbidities, or excessively impulsive acts are present. |

| 2 | Yellow | Dynamic hypersexuality | The subject presents a marked accentuation of the sexual plot, in terms of drive needs higher than the statistical average of the reference population but still falling within the physiological framework or subjective normality, because they do not respond to any existing nosographic pathological profile. He is still able to moderate his behaviour and adapt to the social context, despite feeling an unreasonably more significant drive present than expected, due to age and individual and collective relational context. The fulfilment of these needs is embodied in a greater propulsive drive in the pursuit and realization in practice, but dysfunctional behaviours and paraphiliac comorbidities of mild significance are already present, in the absence, however, of excessively impulsive or egregious acts. |

| Pathological attenuated functioning | |||

| Level | Colour | Definition | Behaviour |

| 3 | Orange | Dysfunctional hypersexuality | The subject presents a significantly marked accentuation of the sexual plot, in terms of drive needs that are higher than the statistical average of the reference population and no longer within the physiological or subjective normal framework. He moderates his behaviour with difficulty, and his functional adaptation to the social context appears coarse and irreverent, precisely because of the markedly more significant sexual drive than expected, due to age and individual and collective relational context. The fulfilment of these needs is substantiated by an excessive propulsive drive in the concrete pursuit and realization, dysfunctional conduct, paraphiliac comorbidities of moderate significance, and impulsive acts out of context are present. |

| 4 | Red | Pathological hypersexuality (grade I) | The subject presents a disproportionate accentuation of the sexual plot, in terms of drive needs that are higher than the statistical average of the reference population and no longer within the physiological framework or subjective normality. He is hardly able to moderate his behaviour and his functional adaptation to the social context appears out of context and often excessive, precisely because of the significantly more pronounced sexual drive than expected, due to age and individual and collective relational context. The fulfilment of these needs is substantiated by an extreme drive in the concrete pursuit and realization, and dysfunctional behaviours, paraphiliac comorbidities of serious relevance, and impulsive out-of-context acts are present; however, he is aware of his acts and is concerned about the possible negative implications in the social context (ego-dystonia) but is not fully attuned to his emotional plan |

| Pathological to corrupt functioning | |||

| Level | Colour | Definition | Behaviour |

| 5 | Purple | Pathological hypersexuality (grade II) | The subject presents a disproportionate and unreasonable accentuation of the sexual plot, in terms of drive needs well above the statistical average of the reference population and no longer within the physiological or subjective normalcy framework. He is unable to moderate his behaviour, and his functional adaptation to the social context appears severely compromised, precisely because of the significantly more pronounced sexual drive than expected, due to age and individual and collective relational context. He exposes himself to danger to himself and others, gives no weight to the negative consequences of his behaviour, and adopts insane, promiscuous, impulsive and instinctive conduct. The fulfilment of such needs is substantiated by an uncontrollable propulsive drive in concrete pursuit and fulfilment, and severe dysfunctional conduct, paraphiliac comorbidities of extreme pathological relevance, and impulsive and irrational acts out of context are present. He is not aware of his acting out (ego-syntony) and his emotional plane, although he may display emotions and feelings that seemingly may prove otherwise. |

5. Conclusions

6. Implications for Clinical Practice

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bernorio, R.; Mori, G.; Casnici, F.; Polloni, G. L’approccio diagnostico in sessuologia. 2020, Franco Angeli Ed.

- Simonelli, C. L’approccio integrato in sessuologia clinica. 2006, Franco Angeli Ed.

- World Health Organization (WHO) ICD-11: International classification of diseases (11th revision). 2022: https://icd.who.int/.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). <b>2013</b>: Washington, DC. American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). 2013: Washington, DC.

- Montgomery-Graham, S. Conceptualization and Assessment of Hypersexual Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sex Med Rev 2017, 5, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Dìaz, P.; Chico-Garcìa, J.L.; Beltràn-Corbellini, A.; Rodrìguez-Jorge, F.; Fernàndez-Escandòn, C.L.; Alonso-Cànovas, A.; Martìnez-Castrillo, J.C. Does the Country Make a Difference in Impulse Control Disorders? A Systematic Review. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2020, 8, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrotta, G. Paraphilic disorder: definition, contexts and clinical strategies. Neuro Research 2019, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. Dysfunctional sexual behaviours: definition, clinical contexts, neurobiological profiles and treatments. Int J Sex Reprod Health Care 2020, 3, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Soldati, L.; Bianchi-Demicheli, F.; Schockaert, P.; Kohl, J.; Bolmont, M.; Hasler, R.; Perroud, N. Association of ADHD and hypersexuality and paraphilias. Psychiatry Res 2021, 295, 113638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korchia, T.; Boyer, L.; Deneuville, M.; Etchecopar-Etchart, D.; Lancon, C.; Fond, G. ADHD prevalence in patients with hypersexuality and paraphilic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2022, 272, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrotta, G. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: definition, contexts, neural correlates and clinical strategies. J Addi Adol Beh 2019, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latella, D.; Maggio, M.G.; Andaloro, A.; Marchese, D.; Manuli, A.; Calabrò, R.S. Hypersexuality in neurological diseases: do we see only the tip of the iceberg? J Integr Neurosci 2021, 20, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codling, D.; Shaw, P.; David, A.S. Hypersexuality in Parkinson's Disease: Systematic Review and Report of 7 New Cases. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2015, 2, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakum, S.; Cavanna, A.E. The prevalence and clinical characteristics of hypersexuality in patients with Parkinson's disease following dopaminergic therapy: A systematic literature review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2016, 25, 10–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.M.; Conti, C.; Prado, G.F. Pharmacological treatment for Kleine-Levin syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016, 5, CD006685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burley, C.V.; Burns, K.; Brodaty, H. Pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches to reduce disinhibited behaviors in dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrotta; G. General overview of “human dementia diseases”: definitions, classifications, neurobiological profiles and clinical treatments. Gerontol & Geriatric stud. 2020, 6, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta, G. Autism Spectrum Disorder: Definition, contexts, neural correlates and clinical strategies. J Neurol Neurother 2019, 4, 2–136. [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta; G. Sleep-wake disorders: Definition, contexts and neural correlations. J Neurol Psychol. 2019, 7, 09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Alarcon, R.; de la Iglesia, J.; Casado, N.M.; Montejo, A.L. Online Porn Addiction: What We Know and What We Don't-A Systematic Review. J Clin Med 2019, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrotta, G. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: definition, contexts, neural correlates and clinical strategies. Journal of Neurology 2019, 1, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta, G. Behavioral addiction disorder: definition, classifications, clinical contexts, neural correlates and clinical strategies. J Addi Adol Beh 2019, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. Bipolar disorder: definition, differential diagnosis, clinical contexts and therapeutic approaches. J. Neuroscience and Neurological Surgery 2019, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. Borderline Personality Disorder: definition, differential diagnosis, clinical contexts and therapeutic approaches. Ann Psychiatry Treatm 2020, 4, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta, G. Narcissism and psychopathological profiles: definitions, clinical contexts, neurobiological aspects and clinical treatments. J Clin Cases Rep 2020, 4, 12–25. [Google Scholar]

- Karila, L.; Wery, A.; Weinstein, A.; Cottencin, O.; Petit, A.; Reynaud, M.; Billieux, J. Sexual addiction or hypersexual disorder: different terms for the same problem? A review of the literature. Curr Pharm Des 2014, 20, 4012–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellini, G.; Lelli, L.; Ricca, V.; Maggi, M. Sexuality in eating disorders patients: etiological factors, sexual dysfunction and identity issues. A systematic review. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2016, 25, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowatch, R.A.; Youngstrom, E.A.; Danielyan, A.; Findling, R.L. Review and meta-analysis of the phenomenology and clinical characteristics of mania in children and adolescents. Bipolar Disord 2005, 7, 483–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, L.; Carvalho, J. The Link Between Boredom and Hypersexuality: A Systematic Review. J Sex Med 2020, 17, 994–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, K.; Hook, J.N.; Davis, D.E.; Penberthy, J.K.; Reid, R.C. Nonparaphilic hypersexual behavior and depressive symptoms: a meta-analytic review of the literature. J Sex Marital Ther 2014, 40, 477–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, T.L.; Lyng, T.; Gleason, N.; Finotelli, I.; Coleman, E. Compulsive sexual behavior, religiosity, and spirituality: A systematic review. J Behav Addict 2021, 10, 854–878. [Google Scholar]

- Landgren, V.; Olsson, P.; Briken, P.; Rahm, C. Effects of testosterone suppression on desire, hypersexuality, and sexual interest in children in men with pedophilic disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry 2022, 23, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.F. Sexually Compulsive Behavior: Hypersexuality (Psychiatric Clinics of North America), Vol. 31, No. 4. 2008, Sauders Pub.

- Walton, M.T. Hypersexuality: A Critical Review and Introduction to the "Sexhavior Cycle". Arch Sex Behav 2017, 46, 2231–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. The strategic clinical model in psychotherapy: theoretical and practical profiles. J Addi Adol Beh 2020, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, J.; Kaldo, V.; Arver, S.; Dhejne, C.; Oberg, K.G. A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Group Intervention for Hypersexual Disorder: A Feasibility Study. J Sex Med 2017, 14, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallberg, J.; Kaldo, V.; Arver, S.; Dhejne, C.; Jokinen, J.; Oberg, K.G. A Randomized Controlled Study of Group-Administered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Hypersexual Disorder in Men. J Sex Med 2019, 16, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schecklmann, M.; Sakreida, K.; Oblinger, B.; Langguth, B.; Poeppl, T.B. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation as a Potential Tool to Reduce Sexual Arousal: A Proof of Concept Study. J Sex Med 2020, 17, 1553–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzittofis, A.; Arver, S.; Oberg, K.; Hallberg, J.; Nordstrom, P.; Jokinen, J. HPA axis dysregulation in men with hypersexual disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 63, 247–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oei, N.Y.L.; Rombouts, S.A.; Soeter, R.P.; van Gerven, J.M.; Both, S. Dopamine modulates reward system activity during subconscious processing of sexual stimuli. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012, 37, 1729–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrotta, G. Oxytocin and the role of “regulator of emotions”: definition, neurobiochemical and clinical contexts, practical applications and contraindications. Arch Depress Anxiety 2020, 6, 001–005. [Google Scholar]

- Cantelmi, T.; Lambiase, E. Schiavi del sesso. 2016, Alpes Ed.

- Cleveland Clinic. Source: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/22690-sex-addiction-hypersexuality-and-compulsive-sexual-behavior.

- Asiff, M.; Sidi, H.; Masiran, R.; Kumar, J.; Das, S.; Hatta, N.H.; Alfonso, C. Hypersexuality As a Neuropsychiatric Disorder: The Neurobiology and Treatment Options. Curr Drug Targets. 2018, 19, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, F.J.; Walters, G.D.; Harris, D.A.; Knight, R.A. Is Hypersexuality Dimensional or Categorical? Evidence From Male and Female College Samples. J Sex Res. 2016, 53, 224–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, M.T.; Cantor, J.M.; Bhullar, N.; Lykins, A.D. Hypersexuality: A Critical Review and Introduction to the "Sexhavior Cycle". Arch Sex Behav. 2017, 46, 2231–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).