Submitted:

19 April 2023

Posted:

20 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

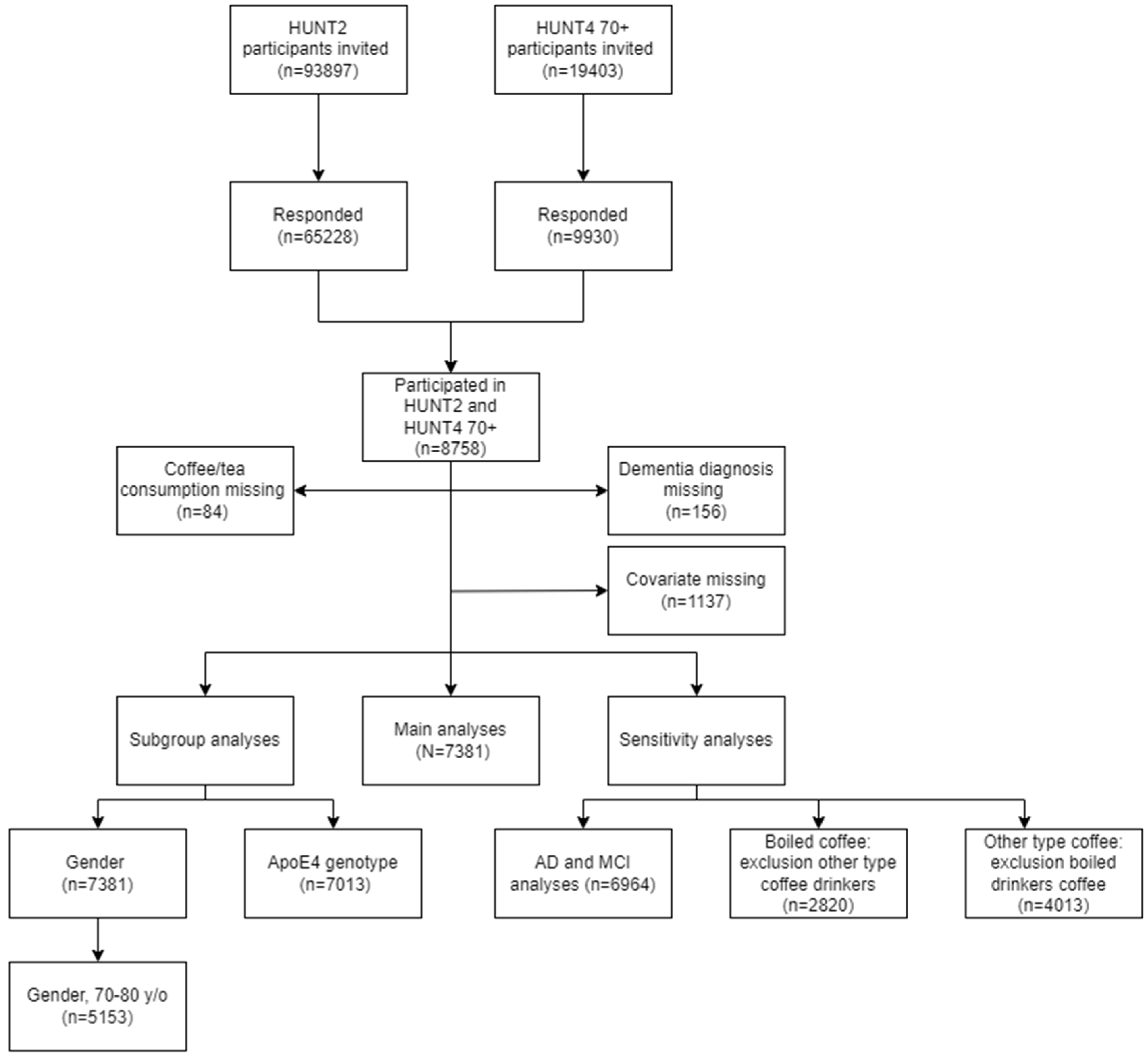

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study population and design

2.2. Exposure assessment

2.3. Outcome assessment

2.4. Covariates

2.5. Statistical analyses

2.6. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Coffee and tea consumption and dementia risk

3.3. Type of coffee and dementia risk

3.4. Coffee, tea and the risk of MCI and AD

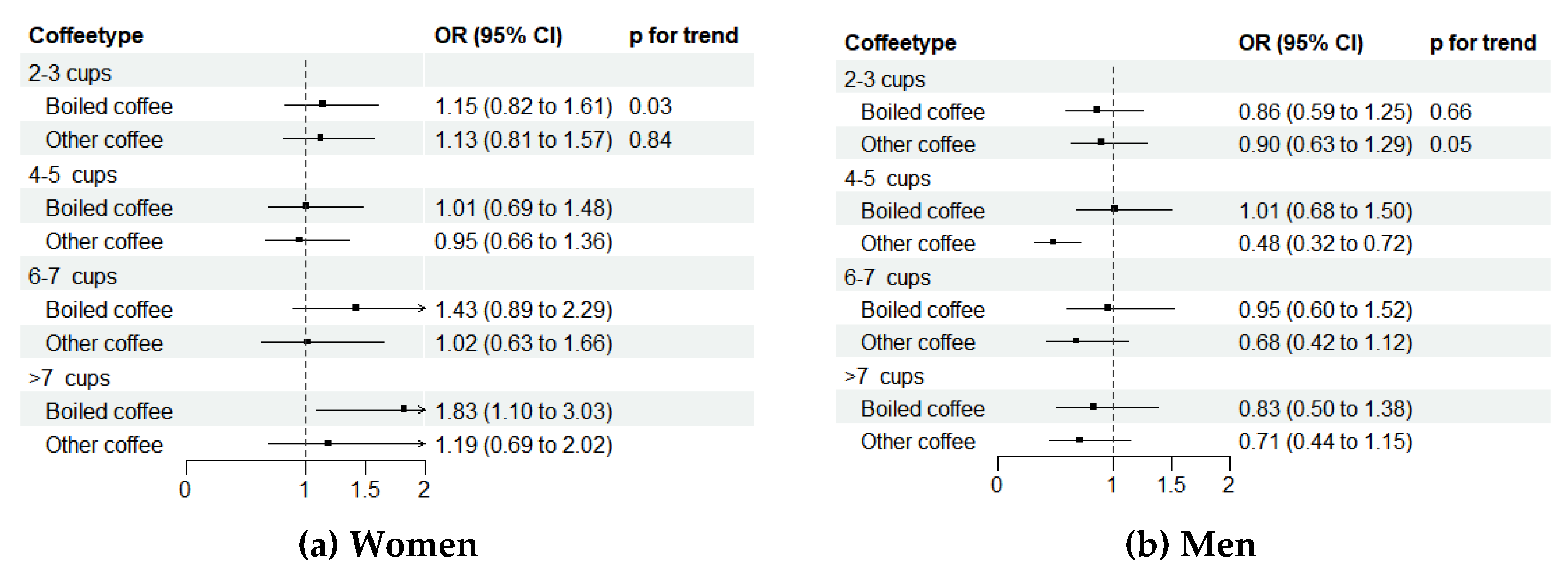

3.5. Sex differences

3.6. ApoE4 carrier status

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 0 |

1 |

2 |

≥3 |

p-value for trend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCI | n | 1571 | 358 | 412 | 211 | ||||

| Ref | 0.91 (0.78-1.06) | 1.07 (0.93-1.25) | 0.95 (0.78-1.16) | 0.91 | |||||

| AD | n | 354 | 84 | 88 | 46 | ||||

| Ref | 0.94 (0.71-1.25) | 0.90 (0.68-1.19) | 1.01 (0.71-1.45) | 0.68 | |||||

| Coffee consumption (cups/day) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 |

2-3 | 4-5 | 6-7 | ≥8 | p-value for trend | |||

| Boiled Coffee | Female | n | 1578 | 403 | 358 | 183 | 161 | |

| Ref | 1.01 (0.57-1.80) | 1.28 (0.69-2.36) | 1.49 (0.73-3.05) | 2.68 (1.35-5.33) | <0.01 | |||

| Male | n | 1454 | 353 | 304 | 174 | 185 | ||

| Ref | 0.47 (0.25-0.85) | 1.02 (0.60-1.77) | 0.52 (0.25-1.09) | 0.78 (0.40-1.53) | 0.47 | |||

| Other type coffee | Female | n | 1083 | 577 | 582 | 254 | 187 | |

| Ref | 1.26 (0.75-2.14) | 0.94 (0.52-1.71) | 1.06 (0.50-2.25) | 1.59 (0.75-3.40) | 0.48 | |||

| Male | n | 1019 | 444 | 494 | 220 | 293 | ||

| Ref | 0.78 (0.46-1.32) | 0.49 (0.28-0.87) | 0.57 (0.28-1.14) | 0.64 (0.34-1.21) | 0.10 | |||

| Sex | 0 |

1 |

2 |

≥3 |

p-value for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | n | 2184 | 635 | 773 | 357 | |

| Ref | 0.96 (0.71-1.29) | 0.97 (0.74-1.28) | 1.33 (0.92-1.92) | 0.39 | ||

| Male | n | 2229 | 497 | 411 | 295 | |

| Ref | 0.89 (0.63-1.26) | 0.92 (0.65-1.30) | 0.72 (0.47-1.10) | 0.15 |

| ApoE4 carrier status | 0 |

1 |

2 |

≥3 |

p-value for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | n | 2950 | 767 | 769 | 42 | |

| Ref | 0.98 (0.74-1.30) | 0.95 (0.72-1.26) | 0.98 (0.69-1.41) | 0.79 | ||

| Positive | n | 1255 | 315 | 348 | 183 | |

| Ref | 0.85 (0.57-1.28) | 0.91 (0.63-1.32) | 1.16 (0.71-1.87) | 0.95 |

References

- Global Burden of Disease Dementia Forecasting Collaborators, Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health, 2022. 7(2): p. e105-e125. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Dementia. Fact Sheets 2022 [cited 2022 02-11]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

- Livingston, G.; et al., Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet, 2020. 396(10248): p. 413-446. [CrossRef]

- Middleton, L.E. and K. Yaffe, Targets for the prevention of dementia. J Alzheimers Dis, 2010. 20(3): p. 915-24. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Ruiz, J.A., D.S. Leake, and J.M. Ames, In vitro antioxidant activity of coffee compounds and their metabolites. J Agric Food Chem, 2007. 55(17): p. 6962-9. [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; et al., Caffeine suppresses amyloid-beta levels in plasma and brain of Alzheimer's disease transgenic mice. J Alzheimers Dis, 2009. 17(3): p. 681-97. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; et al., Caffeine prevents d-galactose-induced cognitive deficits, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in the adult rat brain. Neurochem Int, 2015. 90: p. 114-24. [CrossRef]

- Fredholm, B.B.; et al., Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use. . Pharmacol Rev, 1999. 51(1): p. 83-133.

- Chen, J.Q.A.; et al., Associations Between Caffeine Consumption, Cognitive Decline, and Dementia: A Systematic Review. J Alzheimers Dis, 2020. 78(4): p. 1519-1546. [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, N.; et al., Association of coffee, green tea, and caffeine with the risk of dementia in older Japanese people. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2021. 69(12): p. 3529-3544. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al., Consumption of coffee and tea and risk of developing stroke, dementia, and poststroke dementia: A cohort study in the UK Biobank. PLOS Medicine, 2021. 18(11): p. e1003830. [CrossRef]

- Gelber, R.P.; et al., Coffee intake in midlife and risk of dementia and its neuropathologic correlates. J Alzheimers Dis, 2011. 23(4): p. 607-15. [CrossRef]

- Villemagne, V.L., Burnham, S., Bourgeat, P., Brown, B., Ellis, K. A., Salvado, O., Szoeke, C.,, S.L. Macaulay, Martins, R., Maruff, P., Ames, D., Rowe, C. C., Masters, C. L., Australian, and B. Imaging, Amyloid beta deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer's disease: A prospective cohort study. . Lancet Neurol, 2013. 12(4): p. 357-367. [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.R. and A.D. Roses, Genetics of Alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Neurology, 1991: p. 25-26:41-51.

- Norwitz, N.G.; et al., Precision Nutrition for Alzheimer's Prevention in ApoE4 Carriers. Nutrients, 2021. 13(4). [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., D. Sun, and Y. He, Coffee intake and the incident risk of cognitive disorders: A dose-response meta-analysis of nine prospective cohort studies. Clin Nutr, 2017. 36(3): p. 730-736. [CrossRef]

- Schoeneck, M. and D. Iggman, The effects of foods on LDL cholesterol levels: A systematic review of the accumulated evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 2021. 31(5): p. 1325-1338. [CrossRef]

- Clair, L.; et al., Cardiovascular disease and the risk of dementia: A survival analysis using administrative data from Manitoba. Can J Public Health, 2022. 113(3): p. 455-464. [CrossRef]

- Farnsworth Von Cederwald, B.; et al., Association of Cardiovascular Risk Trajectory With Cognitive Decline and Incident Dementia. Neurology, 2022: p. 10.1212/WNL.000. [CrossRef]

- Gjøra, L.; et al., Current and Future Prevalence Estimates of Mild Cognitive Impairment, Dementia, and Its Subtypes in a Population-Based Sample of People 70 Years and Older in Norway: The HUNT Study. J Alzheimers Dis, 2021. 79(3): p. 1213-1226. [CrossRef]

- Black, D.W. and J.E. Grant, The essential companion to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition 2014: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Holmen, J., Midthjell, K., Krüger, Ø., Langhammer, A., Lingaas Holmen, T., Bratberg, G., Vatten, L., & Lund-Larsen, P. , The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study 1995-97 (HUNT 2): Objectives, contents, methods and participation. Norsk Epidemiologi, 2003. 13(1): p. 19-32.

- Araújo, L.F.; et al., Association of Coffee Consumption with MRI Markers and Cognitive Function: A Population-Based Study. J Alzheimers Dis, 2016. 53(2): p. 451-61. [CrossRef]

- Mirza, S.S.; et al., Coffee consumption and incident dementia. Eur J Epidemiol, 2014. 29(10): p. 735-41. [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; et al., Long-term coffee consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Circulation, 2014. 129(6): p. 643-59. [CrossRef]

- Tverdal, A.; et al., Coffee consumption and mortality from cardiovascular diseases and total mortality: Does the brewing method matter? Eur J Prev Cardiol, 2020. 27(18): p. 1986-1993. [CrossRef]

- Urgert, R., van der Weg, G., Kosmeijer-Schuil, T. G., van de Bovenkamp, P., Hovenier, R., & Katan, M. B., Levels of the Cholesterol-Elevating Diterpenes Cafestol and Kahweol in Various Coffee Brews. . Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 1995. 43(8): p. 2167–2172. [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Kozlow, M.; et al., Coffee consumption and cognitive function among older adults. Am J Epidemiol, 2002. 156(9): p. 842-50. [CrossRef]

- Barp, J.; et al., Myocardial antioxidant and oxidative stress changes due to sex hormones. Braz J Med Biol Res, 2002. 35(9): p. 1075-81. [CrossRef]

- Ide, T.; et al., Greater oxidative stress in healthy young men compared with premenopausal women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2002. 22(3): p. 438-42. [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, Y.; et al., Relationship between coffee consumption, oxidant status, and antioxidant potential in the Japanese general population. Clin Chem Lab Med, 2013. 51(10): p. 1951-9. [CrossRef]

- Mahley, R.W., Apolipoprotein E: Cholesterol transport protein with expanding role in cell biology. Science, 1988. 240(4852): p. 622-30. [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.; et al., Cholesterol, APOE genotype, and Alzheimer disease: An epidemiologic study of Nigerian Yoruba. Neurology, 2006. 66(2): p. 223-7. [CrossRef]

- Wroolie, T.; et al., Effects of LDL Cholesterol and Statin Use on Verbal Learning and Memory in Older Adults at Genetic Risk for Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis, 2020. 75(3): p. 903-910. [CrossRef]

- Eskelinen, M.H.; et al., Midlife coffee and tea drinking and the risk of late-life dementia: A population-based CAIDE study. J Alzheimers Dis, 2009. 16(1): p. 85-91. [CrossRef]

- Almajano, M.P., Carbó, R., Jiménez, J. A. L., & Gordon, M. H. , Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of tea infusions. Food chemistry, 2008. 108(1): p. 55-63. [CrossRef]

- Beresniak, A.; et al., Relationships between black tea consumption and key health indicators in the world: An ecological study. BMJ Open, 2012. 2(6): p. e000648. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; et al., Gender differences in the protective effects of green tea against amnestic mild cognitive impairment in the elderly Han population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2018. 14: p. 1795-1801. [CrossRef]

- Noguchi-Shinohara, M.; et al., Consumption of green tea, but not black tea or coffee, is associated with reduced risk of cognitive decline. PLoS ONE, 2014. 9(5): p. e96013. [CrossRef]

- Kolahdouzan, M. and M.J. Hamadeh, The neuroprotective effects of caffeine in neurodegenerative diseases. CNS Neurosci Ther, 2017. 23(4): p. 272-290. [CrossRef]

- Luca, M., A. Luca, and C. Calandra, The Role of Oxidative Damage in the Pathogenesis and Progression of Alzheimer's Disease and Vascular Dementia. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2015. 2015: p. 504678. [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; et al., Independent and Joint Associations of Tea Consumption and Smoking with Parkinson's Disease Risk in Chinese Adults. J Parkinsons Dis, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ross, G.W., Association of Coffee and Caffeine Intake With the Risk of Parkinson Disease. JAMA, 2000. 283(20): p. 2674. [CrossRef]

- Adu, M.D.; et al., Association between non-tea flavonoid intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: The Australian diabetes, obesity and lifestyle study. Food Funct, 2022. 13(8): p. 4459-4468. [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, P.; et al., Long-term effects of coffee and caffeine intake on the risk of pre-diabetes and type 2 diabetes: Findings from a population with low coffee consumption. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 2018. 28(12): p. 1261-1266. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; et al., Coffee and tea consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease and cancer: A pooled analysis of prospective studies from the Asia Cohort Consortium. Int J Epidemiol, 2022. 51(2): p. 626-640. [CrossRef]

- Krokstad, S.; et al., Cohort Profile: The HUNT Study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol, 2013. 42(4): p. 968-77. [CrossRef]

- Åsvold, B.O.; et al., Cohort Profile Update: The HUNT Study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol, 2022. [CrossRef]

| Coffee consumption (cups/day) | Tea consumption (cups/day) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 0-1 | 2-3 | 4-5 | 6-7 | ≥8 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ≥3 | |||

| Total study population, n |

7381 |

580 | 1770 | 2584 | 1248 | 1199 | 4413 | 1132 | 1184 | 652 | ||

| Sex, male | 3432 (46.5) | 286 (49.3) | 768 (43.4) | 1099 (42.5) | 594 (47.6) | 685 (57.1) | 2229 (50.5) | 497 (43.9) | 411 (34.7) | 295 (45.2) | ||

| Age | 55.85 ± 6.20 | 56.22 ± 6.19 | 56.57 ± 6.56 | 56.18 ± 6.43 | 55.40 ± 5.96 | 54.39 ± 5.36 | 55.76 ± 6.21 | 55.83 ± 6.31 | 56.22 ± 6.47 | 55.90 ± 5.96 | ||

| Educational attainment | ||||||||||||

| Primary school | 2976 (40.3) | 162 (27.9) | 633 (35.8) | 1104 (42.7) | 532 (42.6) | 545 (45.5) | 1918 (43.5) | 363 (32.1) | 454 (38.3) | 241 (37.0) | ||

| High school | 2655 (36.0) | 222 (38.3) | 642 (36.3) | 891 (34.5) | 452 (36.2) | 448 (37.4) | 1578 (35.8) | 425 (37.5) | 432 (36.5) | 220 (33.7) | ||

| College/university | 1750 (23.7) | 196 (33.8) | 495 (28.0) | 589 (22.8) | 264 (21.2) | 206 (17.2) | 917 (20.8) | 344 (30.4) | 298 (25.2) | 191 (29.3) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Unmarried | 310 (4.2) | 42 (7.2) | 70 (4.0) | 104 (4.0) | 47 (3.8) | 47 (3.9) | 197 (4.5) | 42 (3.7) | 41 (3.5) | 30 (4.6) | ||

| Married | 6097 (82.6) | 462 (79.7) | 1457 (82.3) | 2137 (82.7) | 1057 (84.7) | 984 (82.1) | 3635 (82.4) | 945 (83.5) | 984 (83.1) | 533 (81.7) | ||

| Widow(er)/divorced/ separated |

974 (13.2) |

76 (13.1) | 243 (13.7) | 343 (13.3) | 144 (11.5) | 168 (14.0) | 581 (13.2) | 145 (12.8) | 159 (13.4) | 89 (13.7) | ||

| Tea consumption (cups/day) | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 4413 (59.8) | 181 (31.2) | 721 (40.7) | 1595 (61.7) | 935 (74.9) | 981 (81.8) | ||||||

| 1 | 1132 (15.3) | 103 (17.8) | 436 (24.6) | 398 (15.4) | 120 (9.6) | 75 (6.3) | ||||||

| 2 | 1184 (16.0) | 119 (20.5) | 397 (22.4) | 438 (17.0) | 139 (11.1) | 91 (7.6) | ||||||

| ≥3 | 652 (8.8) | 177 (30.5) | 216 (12.2) | 153 (5.9) | 54 (4.3) | 52 (4.3) | ||||||

| Coffee consumption (cups/day) | ||||||||||||

| 0-1 | 580 (7.9) | 181 (4.1) | 103 (9.1) | 119 (10.1) | 177 (27.1) | |||||||

| 2-3 | 1770 (24.0) | 721 (16.3) | 436 (38.5) | 397 (33.5) | 216 (33.1) | |||||||

| 4-5 | 2584 (35.0) | 1595 (36.1) | 398 (35.2) | 438 (37.0) | 153 (23.5) | |||||||

| 6-7 | 1248 (16.9) | 935 (21.2) | 120 (10.6) | 139 (11.7) | 54 (8.3) | |||||||

| ≥8 | 1199 (16.2) | 981 (22.2) | 75 (6.6) | 91 (7.7) | 52 (8.0) | |||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||||||||

| < 25 | 2449 (33.2) | 223 (38.4) | 613 (34.6) | 853 (33.0) | 383 (30.7) | 377 (31.4) | 1392 (31.5) | 407 (36.0) | 403 (34.0) | 247 (37.9) | ||

| 25-29.99 | 3759 (51.0) | 272 (46.9) | 888 (50.2) | 1317 (51.0) | 671 (53.8) | 611 (51.0) | 2286 (51.8) | 575 (50.8) | 597 (50.4) | 301 (46.2) | ||

| 30-34.99 | 939 (12.7) | 61 (10.5) | 210 (11.9) | 333 (12.9) | 163 (13.1) | 172 (14.3) | 597 (13.5) | 113 (10.0) | 146 (12.3) | 83 (12.7) | ||

| ≥ 35 | 234 (3.2) | 24 (4.1) | 59 (3.3) | 81 (3.1) | 31 (2.5) | 39 (3.3) | 138 (3.1) | 37 (3.3) | 38 (3.2) | 21 (3.2) | ||

| Alcohol (units/week) | 1.71 ± 2.22 | 1.27 ± 2.13 | 1.61 ± 2.19 | 1.68 ± 2.13 | 1.78 ± 2.07 | 2.06 ± 2.58 | 1.78 ± 2.36 | 1.68 ± 2.02 | 1.50 ± 1.94 | 1.65 ± 2.12 | ||

| PA (MET-h/week) | ||||||||||||

| ≤8.3 | 3930 (53.2) | 303 (52.2) | 908 (51.3) | 1363 (52.7) | 672 (53.8) | 684 (57.0) | 2439 (55.3) | 558 (49.3) | 618 (52.2) | 315 (48.3) | ||

| 8.3-16.6 | 2273 (30.8) | 168 (29.0) | 575 (32.5) | 812 (31.4) | 393 (31.5) | 325 (27.1) | 1302 (29.5) | 383 (33.8) | 369 (31.2) | 219 (33.6) | ||

| >16.6 | 1178 (16.0) | 109 (18.8) | 287 (16.2) | 409 (15.8) | 183 (14.7) | 190 (15.8) | 672 (15.2) | 191 (16.9) | 197 (16.6) | 118 (18.1) | ||

| Smoking | ||||||||||||

| Never | 3305 (44.8) | 402 (69.3) | 1028 (58.1) | 1186 (45.9) | 441 (35.3) | 248 (20.7) | 1682 (38.1) | 636 (56.2) | 638 (53.9) | 349 (53.5) | ||

| Previous | 2579 (34.9) | 133 (22.9) | 571 (32.3) | 943 (36.5) | 481 (38.5) | 451 (37.6) | 1608 (36.4) | 351 (31.0) | 395 (33.4) | 225 (34.5) | ||

| Current | 1497 (20.3) | 45 (7.8) | 171 (9.7) | 455 (17.6) | 326 (26.1) | 500 (41.7) | 1123 (25.4) | 145 (12.8) | 151 (12.8) | 78 (12.0) | ||

| DM, yes | 141 (1.9) | 14 (2.4) | 32 (1.8) | 49 (1.9) | 29 (2.3) | 17 (1.4) | 69 (1.6) | 25 (2.2) | 31 (2.6) | 16 (2.5) | ||

| CVD, at least one |

179 (2.4) |

11 (1.9) | 43 (2.4) | 59 (2.3) | 26 (2.1) | 40 (3.3) | 120 (2.7) | 25 (2.2) | 20 (1.7) | 14 (2.1) | ||

| ApoE4 carrier status, positive | 2101 (30.0) | 182 (33.1) | 480 (28.7) | 721 (29.4) | 368 (31.1) | 350 (30.3) | 1255 (29.8) | 315 (29.1) | 348 (31.2) | 183 (30.0) | ||

| Cognitive status | ||||||||||||

| No CI | 3840 (55.1) | 331 (61.1) | 927 (55.8) | 1344 (55.1) | 636 (53.6) | 602 (53.0) | 2230 (53.7) | 636 (59.0) | 617 (55.2) | 357 (58.1) | ||

| MCI | 2552 (36.7) | 177 (32.7) | 584 (35.2) | 896 (36.7) | 448 (37.8) | 447 (39.4) | 1571 (37.8) | 358 (33.2) | 412 (36.9) | 211 (34.4) | ||

| Dementia all causes | 985 (13.4) | 71 (12.2) | 259 (14.6) | 343 (13.3) | 163 (13.1) | 149 (12.4) | 610 (13.8) | 136 (12.0) | 155 (13.1) | 84 (12.9) | ||

| AD | 572 (8.2) | 34 (6.3) | 150 (9.0) | 200 (8.2) | 102 (8.6) | 86 (7.6) | 354 (8.5) | 84 (7.8) | 88 (7.9) | 46 (7.5) | ||

| Coffee consumption (cups/day) | Tea consumption (cups/day) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 |

2-3 | 4-5 | 6-7 | ≥8 | p-value for trend | 0 | 1 | 2 | ≥3 | p-value for trend | |

| Model 1 | Ref | 1.16 (0.86-1.57) | 1.09 (0.81 -1.46) | 1.26 (0.91 -1.73) | 1.45 (1.05 -2.01) | 0.02 | Ref | 0.81 (0.66-1.01) | 0.84 (0.69-1.03) | 0.91 (0.70-1.18) | 0.11 |

| Model 2 | Ref | 1.12 (0.82-1.52) | 0.95 (0.70-1.30) | 1.06 (0.75-1.48) | 1.11 (0.78 -1.57) | 0.81 | Ref | 0.92 (0.74-1.15) | 0.92 (0.75-1.14) | 1.02 (0.77-1.34) | 0.71 |

| Model 3 | Ref | 1.11 (0.81 -1.51) | 0.94 (0.69-1.28) | 1.04 (0.74-1.46) | 1.09 (0.77-1.54) | 0.90 | Ref | 0.92 (0.74-1.16) | 0.92 (0.74-1.14) | 1.01 (0.76-1.33) | 0.65 |

| Coffee consumption (cups/day) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 |

2-3 | 4-5 | 6-7 | ≥8 | p-value for trend | ||

| Boiled coffee | n | 4284 | 1123 | 1006 | 511 | 457 | |

| Model 2 | Ref | 1.14 (0.93-1.41) | 1.14 (0.92-1.41) | 1.38 (1.05-1.81) | 1.46 (1.08-1.96) | <0.01 | |

| Model 4 | Ref | 1.01 (0.79-1.30) | 1.00 (0.75-1.30) | 1.19 (0.86-1.66) | 1.26 (0.88-1.80) | 0.17 | |

| Other type coffee | n | 3148 | 1447 | 1540 | 639 | 607 | |

| Model 2 | Ref | 0.96 (0.79-1.18) | 0.67 (0.54-0.82) | 0.80 (0.60-1.07) | 0.86 (0.64-1.15) | <0.01 | |

| Model 4 | Ref | 1.01 (0.80-1.28) | 0.71 (0.54-0.92) | 0.86 (0.61-1.21) | 0.93 (0.65-1.32) | 0.24 | |

| Coffee consumption (cups/day) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 |

2-3 | 4-5 | 6-7 | ≥8 | p-value for trend | ||||

| MCI | Boiled coffee | n | 1405 | 369 | 407 | 199 | 172 | ||

| Ref | 1.03 (0.87-1.22) | 1.41 (1.16-1.70) | 1.29 (1.01-1.63) | 1.11 (0.86-1.43) | 0.04 | ||||

| Other type of coffee | n | 1138 | 462 | 521 | 212 | 219 | |||

| Ref | 0.98 (0.83-1.16) | 0.97 (0.81-1.15) | 0.94 (0.75-1.18) | 1.01 (0.80-1.28) | 0.87 | ||||

| AD | Boiled coffee | n | 279 | 94 | 97 | 59 | 43 | ||

| Ref | 1.15 (0.83-1.58) | 1.37 (0.96-1.95) | 1.85 (1.22-2.81) | 1.65 (1.03-2.53) | <0.01 | ||||

| Other type of coffee | n | 295 | 109 | 92 | 41 | 35 | |||

| Ref | 1.14 (0.83-1.55) | 0.79 (0.56-1.12) | 1.00 (0.64-1.56) | 1.03 (0.64-1.67) | 0.71 | ||||

| Coffee consumption (cups/day) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 |

2-3 | 4-5 | 6-7 | ≥8 | p-value for trend | |||

| Boiled Coffee | Negative | n | 2844 | 753 | 675 | 330 | 310 | |

| Ref | 1.15 (0.84-1.58) | 1.15 (0.81-1.64) | 1.53 (1.00 -2.32) | 1.31 (0.82-2.09) | 0.10 | |||

| Positive | n | 1227 | 314 | 281 | 156 | 123 | ||

| Ref | 0.87 (0.56-1.35) | 0.80 (0.44-1.46) | 1.02 (0.47-1.48) | 1.45 (0.79-2.66) | 0.57 | |||

| Other type coffee | Negative | n | 2070 | 983 | 1031 | 417 | 411 | |

| Ref | 1.14 (0.84-1.55) | 0.77 (0.54-1.09) | 0.81 (0.51-1.29) | 0.86 (0.54-1.39) | 0.19 | |||

| Positive | n | 912 | 392 | 433 | 29 | 181 | ||

| Ref | 0.78 (0.51-1.20) | 0.61 (0.39-0.96) | 0.85 (0.48-1.52) | 1.05 (0.58-1.89) | 0.84 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).