1. Introduction

In recent decades, we have witnessed a proliferation of research on the experiences of Japanese-American internment camp inmates, partly due to institutions' archival work and the American government's release of documentation [

1]. Over the years, debates have raged over what to call these camps. Even though officialdom has spoken of internees, the characteristics of the confinement and the type of life have led many scholars to speak of prisoners and incarceration or imprisonment camps [

2]. For example, it is often quoted that the renowned anthropologist Ruth Benedict composed her pivotal essay on Japanese culture,

The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (1946), without traveling to Japan but through interviewing the inmates of Manzanar. What seems certain is that a group of people who shared common ancestors and a life in a foreign country was imprisoned for the same period and for the same length of time in structures that were created from scratch, in spaces that had not previously been constituted for any other population group.

It is now established that artistic practice in the Japanese American internment camps of the Pacific War was helpful in the daily survival of the internees. Moreover, the release of documentation by the U.S. government, plus the archives that certain institutions continue to receive of objects and images related to that experience, has encouraged research on this field in recent decades.

Recovering and cataloging the works produced, detecting artistic trajectories, and exploring the specific characteristics of particular internment camps have been the most frequent tendencies in studying the art produced in these spaces. However, it remains to relate how the city’s fiction was built with the role that artistic activities played in it, both by the predominant ideology and in revealing the secret history of these so-called 'cities'[

3].

Starting from the idea of 'gender fiction' as a tool for the construction of realities assigned to gender by the audio-visual media [

4], we wonder if there was a 'city fiction' that constructed the experience of city dwellers in spaces that were veritable prisons, which would lead to some extent to endurance for the period of stay in the camps, as well as to the prolonged blindness and failure to recognize the pain inflicted by the government to second-class citizens. To be sure, photographic and artistic tools played a fundamental role in this 'fiction of the city' (both to corroborate and dwell in it sustainably despite its many contradictions).

Recognizing the historical error of the imprisonment of American citizens just for their Japanese ancestry was a step forward in civil rights. This struggle had been intensified by the third generation of these sagas, the Sansei (children of the Nisei, born in America, and grandchildren of the Issei, immigrants from Japan)1. An essential aspect of the delay of recognition of the faults has to do with the official visual documentation on the art schools that were created in the camps and the artistic and handicraft works that were produced in the period that began with Executive Order 9066, signed by Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942.

How did art intervene in constructing a city’s fiction that created feigned realities in the internment camps? Throughout this essay, we will contemplate the following steps:

A fiction of the city was produced from the ideological apparatus of the State. Such an entity is an evolution of its repressive apparatus. The latter is achieved through violence and physical force. The former, through the power of ideology and consensus. The school apparatus, for example, would be a dominant ideological one whose objective is to reproduce the status quo. Ideology is the false consciousness created and represents an imaginary relationship between individuals with their actual conditions of existence (which ultimately become the relationships of production to which it is subject) [

5]. What do they produce in the case that we are examining? Art. The fiction of the city generated the experience of the city, and art intervened in it, as we shall see below.

The conditions of life imposed make this 'fiction of the city' inhabitable.

In doing so, the 'city’s fiction' constructed urban realities, reflected in the Government's exhaustive photographic documentation.

Once the spaces had become inhabitable thanks to the activities of the inmates (furniture, installations...), the need to elaborate aesthetic elements began (this is where the role of art would fit).

At the same time, the State had organized an educational system that included practical artistic subjects at all levels. Art schools were founded.

Subsequently, many artistic products are generated that reinforce the city's fiction in point 1: landscapes that intensify beauty, students' works with references to US culture such as drawings of superheroes, paintings with patriotic symbols, etc. [

6]

But we also find works that include elements that contravene or modify the former city’s fiction of the ideological apparatus of the State.

Therefore, art functions in these contexts with a double game: that of resilience and survival, reinforcing the ideological apparatus of the State, and on the other hand documenting, in the cracks of the system, features of its repressive apparatus.

This manuscript highlights that the metaphor of the city in the context of what was, in reality, prisons (the internment camps) was also, curiously enough, a sustainable stance supported by the consistent reverence of the Japanese people towards nature 2, which translates into the activity of artists, who, in turn, used their scarce resources to ensure the continuity of a life that transformed the idea of prison into the concept of daily life in the city. This effect in the future can be beneficial because, in the current situation of conflicts and migrations, the review of the artistic activity of the past under severe hostility can provide keys to survival and recognition of others, the different, the misfits, and the minorities.

The idyllic image of tranquility in the camps was not actual. Among the postcards that were handed about the spectacular spaces where the inhabitants were going to live, texts such as the following were included:

“July 16. Manzanar,

California. JAPS RELOCATE IN SCENIC SPOT—Evacuated from their homes in vital defense areas, alien and American Japanese have been relocated and are living in homes like these. Mt. Whitney, highest United States Peak, rising in the background, gives a touch of Mt. Fuji-dominated Japanese postcards to the pretty scene. (APNI PHOTO FROM OEM) (GWP 51007 OEM)1942” (

Figure 1)

What greater sense of home for a Japanese in America than to see a simile of Mount Fuji, as if he were in Japan? This was an extreme example of propaganda. Parks [

7] points out that the U.S. government reflected and reacted to public opinion over time and that a review of official documents about the Manzanar camp (released at the convenience of the moment) contrasted an idyllic image (including the 'Art Schools') with other photographs that included incidents involving mistreats that often included injuries and deaths. On the other hand, Nipponese industries have often used such an image of perpetual snow as an ersatz for “Nordic” efficacy and productivity. At the same time, the actual climate tends to be warm and humid.

2. Context: Race Fiction and Hatred of Asian-Ness: Its Contradictory Consequences for Artistic Works in Incarceration Camps.

After the end of the period of isolation known as Sakoku 鎖国 (literally, enchained country), the West rediscovered, awkwardly and gradually, some fragments of what today would be termed " forgotten Japan,” a unitary set of facts product of a singular culture, based on nature that was deliberately subjected to secular isolation. During the last quarter of the 19th century -after the opening of the Meiji restoration - and the first quarter of the 20th century, Japanese fashion and ways triumphed in Europe and America in architecture, garden design, and other art forms 3. As a result, many collectors became interested in Japanese art 4.

Before Executive Order 9066, the skills of the Japanese in design, construction, and landscaping were recognized. Moreover, the Japan Style joined other trends (Spanish Colonial Revival, Italianate, Saracen) that white artists and architects executed. However, Dubrow [

8] points out an important aspect: the people of Japanese ancestry (Issei) were limited to putting their knowledge into practice in their native skills. The Nisei, their descendants, were continually pressured to assimilate into American culture by minimizing signs of cultural difference and ruling out the Japanese language, which most descendants could not utter fluently. This seems to us a mere consequence in the artistic field of that anti-Asian response due to the migratory flows in America, especially on the Pacific Coast [

11], which translated into cases of vandalism, looting, and arson. A paradoxical case is the Hagiwara family, who created a Japanese garden in Golden Gate Park thanks to an agreement with the park’s superintendent. It is one of the most valued signs in San Francisco. However, work on this garden, which occupied the Hagiwara family for nearly 50 years, ended abruptly when the Hagiwara were forcibly removed to internment camps (

Figure 2) [

8].

The change in the life trajectories of the artists after Executive Order 9066 occupies an immense range that includes a variegated casuistry. They all have in common that they were decisive experiences and turning points in their life paths that affected the citizens of Nipponese descent in very different and drastic ways. The field to investigate, in this sense, is overwhelming: the cases of Bumpei Usui (interrogated, not interned), Isamu Noguchi (voluntarily interned, but then withheld without his consent), Mrs. Ninomiya, Hisako Shimizu Hibi and her husband George Matsusaburo Hibi (founders of the art schools in the Tanforan and Topaz camps), Chiura Obata (teacher and director in Tanforan after George Matsusaburo Hibi), Henry Yuzuru Sugimoto (and whose earlier work could not be claimed after his release from internment at Jerome and Rohwer, both in Arkansas, because it had been auctioned off), Jimmy Tsutomu Mirikitani (whose life trajectory was made known in the stunning documentary The cats of Mirikitani), Charles Erabu (Suiko) Mikami (sumi-e specialist, interned at Tule Lake and Topaz), Mine Okubo (interned at Tanforan and Topaz, and as we will discuss later, author of the book Citizen 13660, a graphic memoir of her confinement)… the list is endless.

Interpretation of the consequences of artistic activities in the camps has been controversial over time. For example, Senator Sam Hayakawa’s testimony before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Interment of Civilians in 1981 described life in the camps as "trouble-free and relatively happy" and, after the audible protest of the audience (consisting of internees and descendants), he justified this statement with the following idea: "How else can one explain the tremendous output of these amateur artists who, having free time, created small masterpieces of sculpture, ceramics, painting and flower arrangements?" [

9] (1).

More contradictions are added to this controversial issue, which indicates the idea of the city as a metaphor. Since the 19th century, limitations on Asian immigrants' access to U.S. citizenship had multiplied [

10]. Throughout the century, anti-Asian sentiment was spreading throughout the West. On the one hand, first Hawaii (which would not be recognized as a state until 1959) and then the West Coast of the United States (starting with the gold rush, then with the railroads...) had been welcoming numerous Asian immigrants since the 19th century, while at the same time, resentment was growing. Its seed can be identified in what Europe called 'the Yellow Peril' (

Figure 3). Anti-Asian sentiment in the U.S. was further intensified by enacting the Chinese Exclusion Act, limiting immigration between 1885 and 1943 [

11]. It is also interesting to note that in both images in Fig.3, delicate European female figures, though armor-clad and protected by the holy cross (a), seem to be the preferred objective of the lustful Asian fiends.

It suffices to remember that until 1968, the term 'Asian-American' was not recognized, as if Asians had not been part of that nation. Then, however, there was talk of Japanese, Chinese, Filipinos, Koreans... on American soil. Numerous Asians had served in the U.S. Navy in the Pacific War, but the officers were reluctant to acknowledge a citizenship that was nevertheless demonstrated in acts of patriotism. The uncertainty and fear of civilians interned amid a world conflagration, the dislocation, configured a situation of difficult psychological support5.

This paradoxical treatment is reflected in several contradictions between the hatred against the Asian population (

Figure 3) and the paternalistic and generous propaganda apparatus about where the future immigrants needed to settle, as we have seen (

Figure 1).

In a way, these contradictions would be present in the experience of living in prisons as if they were cities: whether, on the one hand, citizenship and freedom of movement were limited to the civilian population of Japanese ancestry (a long-term consequence of hatred of the Asian, and in the short term of the attack on Pearl Harbor), on the other hand, they were offered the possibility of expressing themselves within the limits of formal school (middle school, high school, etc.) or art schools. The case of Miné Okubo is illustrative of these contradictions. Her delightful book

Citizen 13660 is a graphic novel about her experience in several internment camps. It had different prefaces. In the 1983 edition, she evaluates the outcome of the experience. For the Nisei, the evacuation opened the doors to the world [

12]. She explains that the Nisei were the youngest, and a process of Americanization had developed with them in the classes (not only in art). In the arts, the drawing referents were often superheroes or other motifs that had nothing to do with the visual culture of their elders or their native language [

6]. In addition, there had been a generational break that meant they had more authority than their parents in the eyes of American supervisors (the opposite of the case in Japanese culture). The Sansei, children of the Nisei, barely understood what had happened due to their age. By the 1950s, the history of the Japanese-American internment camps had been forgotten. In the mid-1970s and until 1981, the story was widely reported in the media [

12]. After that, the political movements culminated in recognition and formal apologies for the camps’ existence [

12].

There are quite a few differences between this 1983 perspective and when

Citizen 13660 was published. The War Relocation Authority promoted this graphic novel, the agency in charge of running the camps, together with allies outside the government. It was part of an assimilation and absorption plan that they designed for the Nisei to abandon the roots of their ancestors [

14]. Okubo participated by compiling the text and illustrations and making public statements that set the meaning of her narrative. However, despite these facts, the reading of

Citizen 13660 is twofold: the facts of everyday experiences appear, and it carries a gentle critique of the situation. On the other hand, from today's point of view, Okubo's 1983 words seem naïve since racial minorities continue to be subjected to indignities, discrimination, and mass incarceration. As Christine Hong [

15] pointed out, critics considered Okubo's work to represent the triumph of democracy, as an internee had been allowed to express her own views on incarceration.

We want to note that many derogatory terms for the Japanese and other nationalities in the US do appear in the extraordinary dystopian novel by Philip K. Dick, The Man in the High Castle of 1950.

3. Results: This Is not the City They Showed.

Numerous testimonies of the internees' experiences recounted the uncertainty of being forced to move; no one knew where. From the visual point of view, both the early

Citizen 13660 [

13] and the more recent

They call us enemy [

16] deal with the testimonial result of psychological violence. In both well-known cases, the visual aspect reveals what was hidden inside the camps. However, in our research, we have investigated those elements that became exposed.

First, one must consider the location, topography, vegetation, climate, number of inmates, organization into internal and external spaces, and permanence over time. These variants affected the degree in which artistic activities could create (or detach themselves from) the city's fiction.

However, of course, a fiction of a city, like a figment of gender or race, creates performances of gender, as De Lauretis said. This operates logically on a cultural level. Nevertheless, the images do not bring aroma; they do not freeze or burn. The locations of camps were mostly inhospitable places (especially considering that a great deal of the internees had been living on the California coast, which has a milder climate than the extreme temperatures of the hinterland of the United States). The depiction of wind, sandstorms, and snow blizzards and how these atmospheric phenomena affected the inmate population constitutes a large part of the pictorial and draftsmanship work done in the camps. They echo the remark of the philosopher Watsuji, in the sense that

history can never be separated from climate [

17]. Suppose that our findings consist of numerous artistic works based on copying which was performed in the camps. In that case, we would prove that more personal and original pieces describe the population's distress due to the weather adversities. Appendix 1 shows a selection of artworks (moreover paintings) in which the theme of the atmospheric phenomena is detected using a bibliographic survey.

The mere relocation into a new place was already an act of dispossession or exile, therefore, of violence. However, the consequences affected daily life if the area was barren and inhospitable. The dust and snow storms, the extreme hot and cold temperatures, and the wind that constantly accompanied the internees are expressed pictorially in numerous works. The titles are illustrative: "Dust Storm in Topaz,” "Winter Snowstorm,” "Cloudburst in Poston,” etc.

On the other hand, overcrowding and insalubrious conditions were shown pictorially and graphically by describing the interiors of the Mess Halls or the barracks, the communal laundry, or other spaces that showed that families and single inmates had already lost their privacy. The testimonies of inmates spoke of unsanitary conditions, but these were difficult to describe pictorially. At least Miné Okubo succeeded by surrounding the inmates with gnats in her illustrations. Henry Sugimoto's paintings, which he called Documentaries, also demonstrated these realities. For example, the oil on board “Documentary, Our Washroom, Jerome camp" (1942)9 depicted people washing themselves and at the same time cleaning clothes or kitchen utensils, and "Documentary, Our Mess Hall" (1942) 10 included background posters with instructions such as "No Second Serving!" and "Milk for Children and Sick people only." These graphic descriptions are not associated with an idea of a city but of confinement at an internment camp or sites that contravened the fiction of a cozy and livable place with which we began our manuscript.

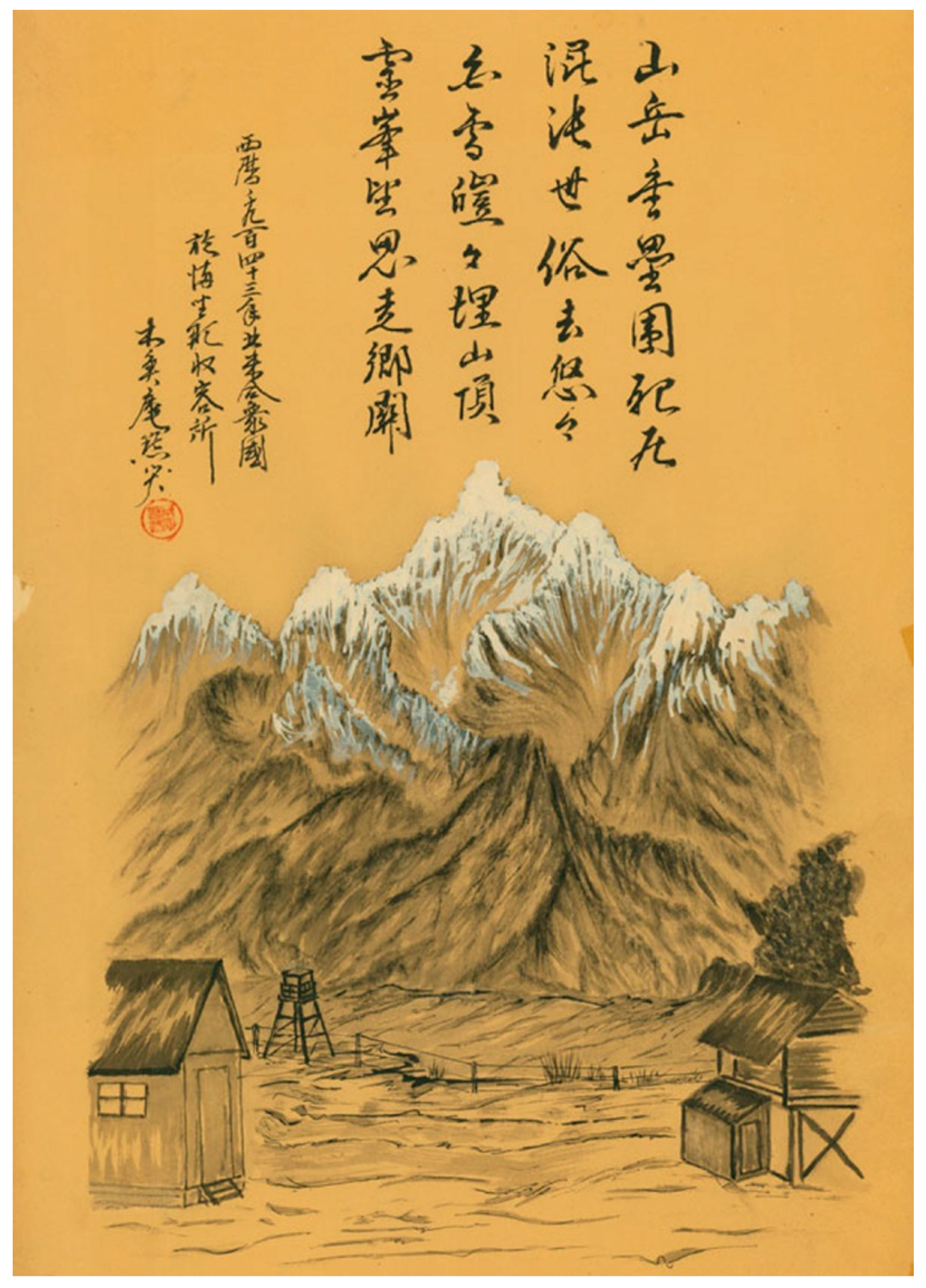

We saw that the internment camps were offered as charming spaces for settlement in a proposal for a pleasant city to inhabit because of the scenarios they offered (

Figure 1). Moreover, this proposal would have continuity through artistic experiences. By granting something akin to the very origins of the Issei, the inmates could approach inner peace through nature, inducing them imaginatively or through meditation in the quest for Nippon (

Figure 5).

This anonymous painting and its poem, which follows the dynamic of text-to-image interaction of the Japanese pictorial tradition, reflects a state of transcendence in its upper part. However, it is an uninhabited space, albeit a sublime one. The lower part of the image takes us to the reality of barbed wire fences and watchtowers. Are those the limits of a city? Nay, they would rather be those in prison or a concentration camp. The image (

Figure 5) elucidates the limiting elements of Manzanar's internment camp. Meanwhile, this anonymous painting presents them in the image, but in the text, it seems as if the spirit could move, in such entwinement with nature, to the highest peaks, in a sort of mysticism linked to the homeland. Thus, what may be contemplated as the assimilation of the government's proposal on inhabiting a city at first sight, suddenly surmises a hidden revelation. The poem is written in Chinese, not even in Japanese. Who could read it? The signature is illegible: Is it not an image that accepts the government's proposal and puts it into practice but adds some concerns that must remain secret? In other words, this document employs different codes from the ones used in the environment where the text is to be read. The idea of self-protection seems to be concealed by using such codes, which must remain secret and forbidden. This idea of misleading images (that stem from familiarly pleasant frameworks) is repeated in many documents.

Barbed wire fences, watchtowers, and armed soldiers are often incorporated into paintings as allotopias (a discordant element to what is expected within a genre), often without becoming the thematic focus. For example, Sugimoto's Cezannian-style country recreation scene

11 depicts a military guard in a corner. In this case, the artist relates that he did not know how to answer for his 5-year-old daughter, who did not come home after a picnic [

18]. In another case, in the background of a still life containing fruit, flowers, a bible, and an Arkansas newspaper, he shows a watch tower in the distance. The "cartoon" style seems more commonly adapted to disguise controversial or problematic themes. It is the case of the oeuvre of Kango Takamura, a photo retoucher at RKO Studios until the Second World War. He recalled: “As you know, we cannot use any camera. So I thought sketching’s all right. But I was afraid I was not supposed to sketch. Maybe government doesn’t like that I sketch…. So I work in a very funny way purposely, made these funny pictures“ [

18] (pp. 119-120). In a few cases, barbed wire fences, the barriers that indicate that the population is incarcerated, become the main object depicted in the paintings. For example, this occurs in a cubist decomposition in watercolor entitled

Minidoka, barbed wire montage by Takuichi Fujii

12 and many others from his Diary, in highly expressionistic charcoal drawings by Miné Okubo with an intense trace of the Mexican muralism that was part of her artistic training, in Estelle Ishigo’s

Children flying a kite, where the kite is trapped by the barbed wire, or in the graphic representation of traumatic events such as death by shooting beside a fence (the case of

Hatsuki Wasaka shot by MP, a drawing by Chiura Obata on 11 April 1943, in Topaz). Riots, fires, and assaults were occasionally depicted -for instance, in

Poston Strike Rally, a watercolor by Gene Sogioka [

18] (p. 153). However, they can be considered exceptions to the usual exercises during art classes.

4. Discussing the Role of Art and Art Schools in Internment Camps—Ways towards Sustainability.

Along with the sense of loss, Dusselier [

9] indexes survival's physical and mental landscapes and establishes two steps. First, it was necessary to improve the degraded living conditions. The inmates created all kinds of furniture from discarded wood and cardboard pieces, tree branches, slats left by government carpenters, etc. After their furniture needs were barely satisfied, they focused on aesthetic issues and decoration. Here is when the activity of needlework, wood carvings, ikebana, paintings, shell art, etc., developed further. Undoubtedly, both aspects of activity focused on creating living environments, that is to say, on creating a city, on putting into practice the metaphor that the government itself had disseminated. When the internees created flower gardens and orchards, roads, and finally, Japanese gardens, it seemed that the image projected by the American government was being put into practice. Let us remember that the Japanese garden, unlike the French geometric garden, initially intends to recreate the unaltered scenarios of Nature.

On the other hand, the relationship with space was embedded in the peculiarities of each terrain, and the use of materials led to the creation of specific objects. In Topaz and Tule Lake, women collected things from the soil: "tiny shells from which brooches and decorative plaques were made. Kobu evolved into a significant art form in Rohwer and Jerome, Arkansas. Discarded fruit crates were essential for furniture makers, weavers used weeds and grass to make hats, and clay provided material for sculptures and crockery. In this way, incarcerated Japanese Americans employed physiological landscapes to refurbish the place" [

9] (p.161).

We witnessed, therefore, an overcoming of hostile conditions by virtue of motivating activities that created a sense of the city, a fact that the government took great care to document. At the same time, the desire for survival and projection into the future that sustainability implies did act to the detriment of recognizing the victims’ pain, as we saw above. This implies a perverse mentality because if the Issei and Nisei had not acted this way, they probably would not have endured. To use that argument is to blame the victim for wanting to keep up living6.

Without knowing how long the situation would last, we cannot deny the sustainable attitude that resulted from these activities: their descendants could even inherit that internment camp. The uncertainty of the new times created habitable spaces also for the future. Ironically one can only wonder about the aftermath in the inmates of the advent of a hypothetic “liberation” force from Japan.

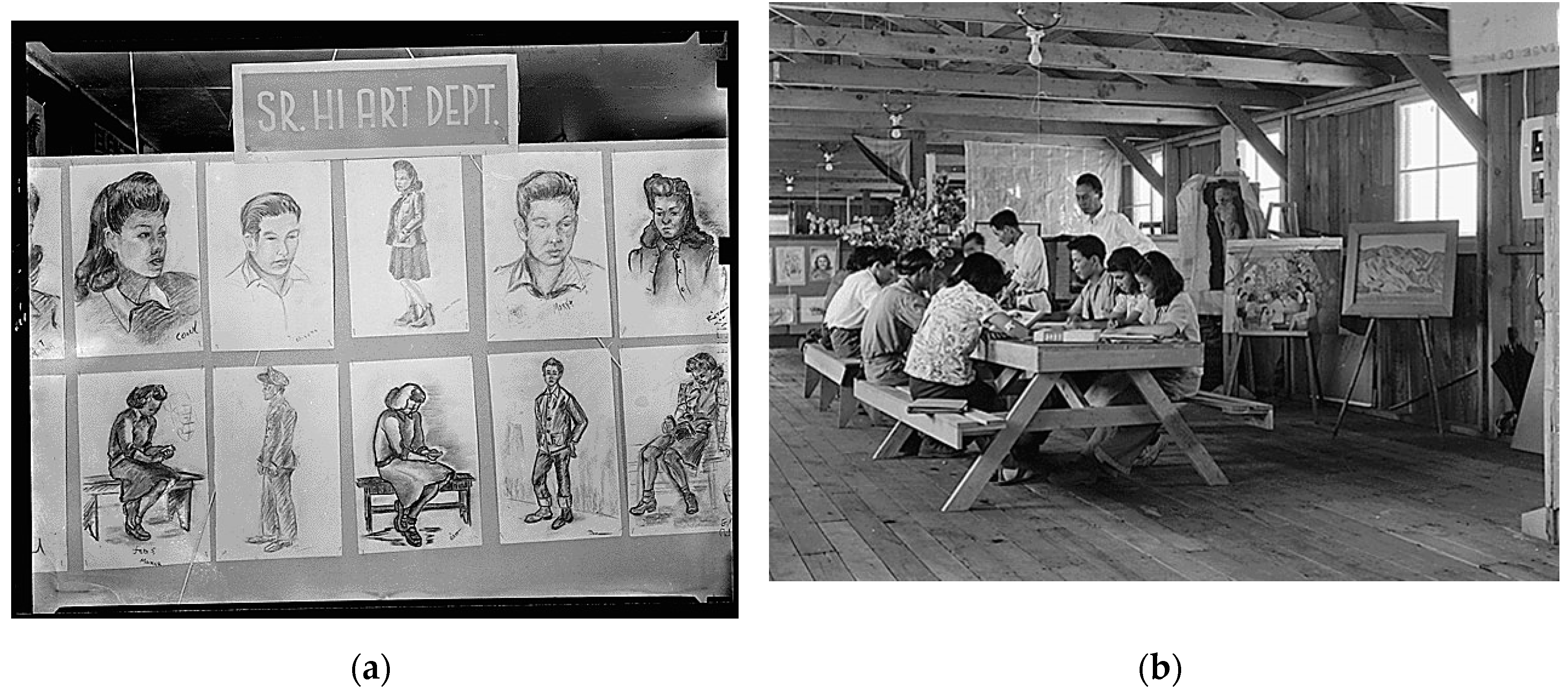

Art also allowed the establishment of community activities [

19]—the exhibitions supported and reformed new family and friend links (

Figure 6). Artistic creation conveyed emotional and mental well-being within the oppressive environment of an internment camp, and participation in art classes and exhibitions enhanced emotional comfort to the level of relationships as well [

9]. Material objects were not something static that fulfilled their function once such were finished but became objects that empowered the psyche, allowed for relationships with one another, and facilitated the fabric of community and city, that is, machi-zukuri in Japanese. Art helped to acknowledge the painful losses of the past, recognizing that such damage would never be erased or banished. Instead, the said works imply an engagement with grief because this process helps us to imagine and give birth to more humane, sustainable futures.

Curiously enough, the WRA and the FBI wanted to destroy these group links when the internees were released. So they forced them to promise to avoid other Japanese American persons who left the camp [

14]

7.

Other aspects of sustainability should be emphasized in this performance of art in the camps.

Firstly, the photographic documentation and the event that the schools were formed have helped to ensure that practically the majority of the preserved work of these artists corresponds to the period of internment or their later artistic activity. It should be noted that the Hibis, like many others, had to give away their earlier work when they were incarcerated in the internment camps. In the case of George Hibi, part of his work is preserved in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Although the artistic practice was present, these units have gone down in history as the 'silent Americans' [

20,

21]. The Nisei did not want to discuss their experience, nor could psychosocial healing arrive from silencing the systemic violence perpetrated against them. It is to this silence endurance that they call Gaman我慢, to resist the unbearable with patience and dignity [

20]. A Zen Buddhist principle that we can link to sustainability. The word gave rise to the name of an exhibition at the Renwick Gallery in Washington D.C., next to the White House, which gives an idea of the re-acknowledgment of the political mistake made. The exhibition was called

The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942-1946 [

20] and ran for nine months between March 2010 and January 2011. This exhibition and the one held in 1992 entitled

The View from Within: Japanese American Art from the internment camps, 1942-1945 (Wight Art Gallery, 13 October to 6 December 1992) [

22] indicate that the work of recognition and reparation includes the extensive effort to catalog artists, artisans and works produced during the internment.

Another interesting idea related to the sustainable dimension of the situation is to think of these citizens as the holders of supernatural citizenship, in the sense of the cases in which they prove with their deeds (in this study, the artistic work, but also the activity to have a more inhabitable space), a way of sustaining democratic principles when the government itself forgets them [

23].

When Miné Okubo graphically describes the tasks of improving space, she is abandoning the idea of the 'bad subject' that was widespread. In this sense, a model citizenry would not resist and combats the inanities of a misguided state, as we might expect at first, but would be forged by flexible survival strategies of Asian Americans, which can transcend binary assimilation of resistance.

“Although it may seem counterintuitive, supernatural citizenship counteracts the power imbalance between citizen and state by highlighting the necessity for forgiveness. Performances of divine citizenship—in which individuals bear witness to the wrongs of the state, deliberately practice forgiveness, and look forward to a new and different future—place the power for transformative change in the hands of those groups who have endured traumatic experiences, as have the Japanese Americans.” [

23] (p. 90). Citizenship is projected as a condition of social membership produced by personal acts and values. In these cases, the behavior of many internees can be read as an act of heroic pedagogy (or Divine Citizenship in the words of Sokolowski [

23].

The machinery for producing race fiction was added to the production of city fiction for the internment camps. In this machinery, art schools functioned as materializing agents of the city itself. The school, that ideological apparatus of the state, would watch over the creation of imaginaries, about who is the enemy, for the control of the bodies of the internees. Moreover, what better control than that which came from themselves? Hence, most of the images produced by the internees were neither problematic nor controversial. On the contrary, acting by the fiction of the city that had been hereby promulgated could lead to their survival. Moreover, here the artistic activities reflect, as we have seen, sundry responses and accommodations of the mind.

5. Conclusions

The comparison of survival strategies through the generation and teaching of fine arts and handicrafts tells us of a search for emotional and physical sustainability within the uncertainty and hardship of the situation. Even from the point of view of recycling, the activities with the debris of the few materials at those infamous centers where no visual or graphic material was provided speak to us of a spirit of survival with the little leftovers in the words of Junichiro Tanizaki's

Praise of Shadows [

24]. Apart from sumi-e painting, which occurred everywhere, other examples such as miniature landscape painting on polished stones have appeared in particular places (in this case in Amache), pictorial decoration of small carved objects, and paintings on canvas in enclaves where art schools were set up to make the passing of time more bearable. Nor can we forget a curious germ of creation related to the Japanese garden. The Japanese garden arose as a three-dimensional recreation of landscape paintings, and curiously, numerous orchards and gardens were upheld throughout the internment.

To control and maintain order in the camps, the government implemented policies to secure the internees’ occupation and bare satisfaction—one such policy developed through encouraging creative expression through art and literature. In the internment camps, the government established programs to support the production of fiction, poetry, and other creative works realized by internees.

The consequences of this policy varied. On the one hand, it allowed some people to express their creativity and provided a sense of purpose and accomplishment in a complex and oppressive situation. However, on the other hand, it also allowed for documenting their experiences and perspectives, which can serve as a valuable historical record of the confinement period, not unlike the actual receding pandemics.

Nevertheless, the government censored the production of fiction and other creative works which intended to control the internment narrative and maintain a positive image of the camps. This censorship could lead to self-refraining among individuals, stifling their ability to express themselves fully.

Moreover, the encouragement of creative expression in the camps did not negate the fact that the internment violated the civil rights of individuals and enacted a traumatic experience that presented long-lasting effects on them and their communities.

The artistic responses by internees of Japanese American camps are a form of cultural sustainability. By creating art, people could maintain and express their cultural heritage and identity, allowing them to still retain a sense of community and self-identity during forced relocation and discrimination.

Furthermore, the artistic responses created by subjects possess a lasting cultural value, as they record the experiences and perspectives of those who endured living in the internment camps. These works can help future generations understand the internment’s impact on individuals and communities and their pining. In addition, they would act as a reminder of the need to protect civil rights and prevent discrimination.

However, it is essential to note that the artistic responses alone do not constitute a particular case of sustainability. Sustainable solutions require addressing the root causes of the problem, in this case, systemic racism and discrimination that led to seclusion. Moreover, it is necessary to promote equity, justice, and inclusion to prevent similar injustices from happening in the future.

The government planned the fiction of the city and how cities were imagined, constructed, and represented. Just as gender is a social construct shaped by cultural and historical forces, cities are also constructed and given form by social, political, and economic strains. The representation of cities in fiction may reflect specific cultural ideas and values while modeling our understanding and perceptions of urban spaces and communities. The development of art in the internment camps that we have analyzed demonstrated that the contemplation of the sad reality of the internees paradoxically enriched the fiction of the city presented.

On the other hand, the space where these minorities were forcibly settled and which, after having functioned as cities, had been abandoned and dismantled after the Pacific War should not be considered a mere recollection of the past since the recognition of such historical heritage still remains topical.

Author Contributions

J. C-L re-writing and conceptual supervision. I. R-C. original manuscript writing.

Funding

This research was funded by EU, NextGenerationEU, through Ministerio de Universidades and University of Seville, grant number 19994.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Jialei Wu for helping to translate the Chinese text in Figure 5. They also appreciate the wisdom and experience of Mr. Aitor Lanjarin-Encina and the Department of Art and Art History of the Colorado State University, the help and generosity of Mr. Jonathan Carlyon, Chair of the Department of Languages, Literatures and Cultures of the Colorado State University, the open-mindedness and efficacy of Erin Tomkins (International Student and Scholar Services of CSU), and Gretchen Zarle-Lightfoot (assistant to the editor of Confluencia, Revista Hispánica de Cultura y Literatura). Moreover, we would like to highlight the extraordinary assistance of the International Women’s Club of Fort Collins International Center, especially from Sara Hunt. We cannot forget the expertise and kindness of Karen Smith (English teacher at Fort Collins International Center) and our deep love for the outstanding ELS instructor Andrea Heyman. In addition, we thank the careful and generous work of the Front Range Community College staff in Fort Collins.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Information about the Painting |

Author |

Origin |

Title 4 |

|

Topaz Duststorm. August 1945. Watercolor. |

Chiura Obata |

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p. 46. |

Wind, dust |

| Topaz at night |

Suiko Mikami |

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p. 64 |

Snow |

|

Duststorm in Poston. Oil. |

Frank Kadowaki |

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p.48 |

Duststorm |

|

Duststorm (Topaz) Tempera |

Miné Okubo |

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p. 72. |

Wind, dust |

|

Wind and Dust, 1942. Gouache on cardboard. 19”x24”. |

Miné Okubo |

Collection of the Miné Okubo Estate |

Wind, dust |

| Untitled (Winter Internment Scene) ca. 1943. Oil on canvas. 48”x40”. |

George Matsusaburo Hibi |

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p. 79 In Japanese American National Museum. Los Angeles. Gift of Ibuji Hibi Lee, 99.63.17. |

Snow |

|

Topaz in winter. Woodcut. |

Matsusaburo Hibi |

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p. 90 |

Snow |

| The same artwork as Untitled (Topaz, Utah) (1943), woodcut, 6 x 8.2 cm. Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts. Gift of Mrs. Hisako Hibi. 1997.102.2. |

Matsusaburo (George) Hibi, |

https://www.jstor.org/stable/26350652

Schultz, 2015, p.4. |

Snow |

|

Snowstorm at Topaz (1944). Watercolor. |

Suiko Mikami |

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p. 102 |

Snow, wind

|

|

A day in February (Topaz, 1945) |

Hisako Hibi |

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p. 107 |

Wind, Dark clouds |

|

Lucky Cloud (Santa Fe) |

Kango Takamura |

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p. 121 |

Big cloud |

At evening Sketched this Beautiful Unusual Cloud Formation. 1942. Watercolor 10”x15”.

(This work and the previous one are very similar). |

Kango Takamura |

Higa 1992, p. 84. Department of Special Collections. University Research Library, UCLA |

Big cloud |

|

First impression of Manzanar (June 1942) |

Kango Takamura |

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p. 122 |

Wind |

|

Winter snowstorm (Manzanar, February 22, 1944) |

Kango Takamura |

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p. 127 |

Snowstorm |

|

Cloudburst at Poston. Watercolor |

Gene Sogioka |

Gesenway and Roseman 1987, p. 127 |

Cloudburst |

| Illustrations of pages: 56, 182 (windy and dusty), 122, 123, 127 (cloud of dust), 145 (first snow), 183, 184, 185 (wind), 189, 190 (heat) |

Miné Okubo |

Okubo, 1946 |

See first column |

|

Forced Removal, Act II. 1944. Oil on canvas. 24”x30”. |

Byron Takashi Tsuzuki |

Higa 1992. Collection of August and Kitty Nakagawa |

Wind |

|

Dust Storm, Topaz, (1943). Watercolor on paper, 14 1/4 x 19 1/4 in. Private collection. |

Chiura Obata |

https://www.crockerart.org/oculus/chiura-obata-an-american-modern |

Duststorm |

|

Gathering coal at Heart Mountain Relocation Camp, 1945. |

Estelle Ishigo |

Department of Special Collections/UCLA Library Estelle Ishigo |

Wind, snow |

Notes

| 1 |

It is the Sansei, through the Japanese American Citizens League, in their Redress movement, who finally succeeded in 1988 in getting the U.S. Congress to pass the Civil Liberties Act, which provided a presidential apology and a symbolic payment of $20,000 to people whose civil rights had been violated by the federal government during World War II. |

| 2 |

To some extent, this article resonates with another research that we have published about Antonin Raymond, a Western architect strongly influenced by Japanese philosophy, and where we have glimpsed suggestive elements of sustainability [ 25, 26] |

| 3 |

One example is that the Freer Gallery and the Sackler Gallery (part of the Smithsonian network of museums in Washington, specifically the Asian Art Museum) house part of the legacy of Tessai Tamioka, who became the official painter to the Meiji Emperor in 1907. The attention that collectors Freer and Arthur M. Sackler paid to this painter, who followed the Chinese tradition in Japan, is well documented in the Cowles Collection and the exhibition Meeting Tessai: Modern Japanese Art from the Cowles Collection. The economic wealth of American collectors implies an abundance of examples of Asian art in U.S. museums. On the other hand, in other writings, we have recovered Fenollosa's fundamental work in spreading the culture of Japan in the West, especially in America [ 27]. |

| 4 |

With the reactivation of maritime trade with Japan, Japanese prints, ceramics, and textiles quickly became popular in Europe and America. In this context, Japonaisserie began to seduce the Western artistic avant-garde. This influence of Japanese culture began with collecting manufactures and mainly works of art. The Meiji Era showed in the West works with visual budgets foreign to Europeans. Van Gogh, Toulouse Lautrec, and practically their entire generation had seen the images that enveloped the ceramics brought from the East; Mackintosh (Charles Rennie and Margaret) had received the publication Le Japon Artistique by Sigfried Bing (1888-1891), published in French, English, and German. |

| 5 |

For example, in Los Angeles, at the Japanese American History Museum, a newspaper text is displayed in which the reporter clarifies that despite his Asian features, he is Chinese, not Japanese". There was, therefore, a fear of being mistaken for a Japanese because the consequences in his life would not be at all good. |

| 6 |

To draw a parallel with a very distant case of violence, we would like to bring up the argument that a gang rape did not occur because the victim, days later, was trying to get her life back on track, go out, go with friends, etc. This argument in Spain was used against the La Manada gang rape case victim and implied a rethinking of the trial to the victims, not the rapists [ 28]. |

| 7 |

This did not happen, and the released internees gathered in enclaves because of internal (religion or affinity) and external (racial hostility and exclusion) factors [ 14]. |

| 8 |

On March 18, 2022, President Biden signed a Democratic-Republican bill designating the Amache property, the Relocation Center in Granada, Colorado, as a National Historic Site. Since that date, the Granada Relocation Center has been owned by the State and overseen by the National Park Service. Previously, the Amache Center was owned by the Granada City Council until its transfer to the National Park Service. The Granada Relocation Center has been recognized as a National Historic Monument. Much of the work to preserve the site had been done by students of the Amache Preservation Society (APS) of Granada High School under teacher/principal Mr. John Hooper. According to Biden, this action "will permanently protect the site for future generations and help tell the story of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. " [ 29] |

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

“Recreation time,” by Henry Sugimoto. 1942. [ 18] (p.34) |

| 12 |

|

References

- Suzuki, T. Wandering the Web--Exploring Information of Japanese Americans' Experiences in Internment Camps during World War II, Against the Grain. 2016. Vol. 28: Iss. 1, Article 39. [CrossRef]

- Camp, S. L. Landscapes of Japanese American Internment. Historical Archaeology, 2016. 50(1):169–186.

- Mehta, S.. La vida secreta de las ciudades. Barcelona, Penguin Random House. 2017.

- De Lauretis, T. Technologies of Gender. Essays on Theory, Film and Fiction, London, Macmillan Press. 1989.

- Althusser, L. Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. (Notes towards an investigation). In Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. 1971. New York and London, Monthly Review Press pp. 142–7, 166–76. Available at: https://mforbes.sites.gettysburg.edu/cims226/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Week-3b-Louis-Althusser.pdf.

- Wenger, G. M. History Matters: Children's Art Education Inside the Japanese American Internment Camp. Studies in Art Education, 2012. FALL 2012, Vol. 54, No. 1, pp. 21-–6. National Art Education Association Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24468128.

- Parks, K. R. Revisiting Manzanar: A history of Japanese American internment camps as presented in selected federal government documents 1941–2002. Journal of government information, 2004, Vol.30 (5), p.575-593.

- Dubrow, G. The Architectural Legacy of Japanese America In Finding a Path Forward, Asian American and Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks theme study. 2017. Edited by Odo, Franklin. Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior pp. 161-187.

- Dusselier, J. E.. Artifacts of Loss: crafting survival in Japanese American concentration camps. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press. 2008.

- Thiesmeyer, L. The discourse of official violence: anti-Japanese North American discourse and the American internment camps Discourse & Society, 1995, Vol.6 (3), p.319-352 London-California: SAGE Publications.

- Spence, J. D. The Chan’s Great Continent: China in Western Minds. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 1998.

- Okubo, M. Preface from the 1983 edition of Citizen13660, Amerasia Journal, 2004, 30:2, 9-14. [CrossRef]

- Okubo, M. Citizen 13660. AMS Press. Nueva York 1966.

- Robinson, G. After Camp: Portraits In Midcentury Japanese American Life and Politics.E-book, Berkeley: University of California Press. 2012. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb33065.0001.001.

- Brown, M. S. [Review of Citizen 13660, Classics of Asian American Literature, [1946], by M. Okubo]. The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 2014, 105(4), 199–199. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24632141.

- Takei, G., Eisinger J., Scott S. They called us Enemy. Marietta, Georgia: Top Shelf Productions. 2019.

- Watsuji, T. Climate and Culture. A Philosophical Study. Greenwood Press: University of California. 1988 [1927].

- Gesenway, D., Roseman, M. Beyond words: Images from Amerioca’s Concentration Camps. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. 1987.

- Kamp-Whittaker, A., Clark, B. J . Social Networks and the Development of Neighborhood Identities in Amache, a WWII Japanese American Internment Camp. Archeological papers of the American Anthropological Association, 2019, Vol.30 (1), p.148-158. Wiley Subscription Services, Inc. Arlington.

- Hirasuna, D. The art of gaman: Arts and crafts from the Japanese American internment camps, 1942-1946 Ten Speed Press.Berkeley, California. 2013.

- Nagata, D. K, Kim, J H. J ; Wu, K.; Hall, G. N.; Kazak, A. E; Neville, H. A; Comas-Díaz, L. The Japanese American Wartime Incarceration: Examining the Scope of Racial Trauma.The American Psychologist, 2019, Vol.74 (1), p.36-48. American Psychological Association. United States.

- Higa, K. M. The View from Within: Japanese American art from the internment camps, 1942-1945 : Wight Art Gallery October 13 through December 6, 1992. University of California, Japanese American National Museum, Asian American Studies Center. Los Angeles. 1992.

- Sokolowski, J. Internment and Post-War Japanese American Literature: Toward a Theory of Divine Citizenship The Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States Melus, 2009, Vol.34 (1), p.69-93. Oxford.

- Tanizaki, J. Elogio de la sombra. Madrid: Siruela. 2015.

- Almodovar- Melendo, J.M., Rodríguez-Cunill, I., Cabeza-Lainez, J. The Search for Solar Architecture in Asia in the Works of the Architect Antonin Raymond: A Protracted Balance between Culture and Nature. Buildings 2022. 12 (10) 1514; [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Lainez, J.; Almodovar-Melendo, J.M.; Rodríguez-Cunill, I.. The search for sustainable architecture in Asia in the oeuvre of Antonin Raymond: a new attunement with nature. Sustainability 2022. 14 (16) 10273 . [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Lainez, J. M.; Almodovar-Melendo, J. M., Rodríguez-Cunill, I.. Ernest Fenollosa, Kakuzo Okakura y el arte japonés. Un diálogo fructífero entre Oriente y Occidente. Ucoarte. Revista de Teoría e Historia del Arte 2022. 11, pp. 123-139. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, C. E. El caso de ‘La Manada’: cuando se culpa a la víctima y no al agresor. Medios de comunicación y usuarios de las redes sociales han juzgado el comportamiento de la víctima tras poner la denuncia. Huffpost November 17th 2017. Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.es/entry/el-caso-de-la-manada-cuando-se-juzga-a-la-victima-y-no-al-agresor_es_5c8aca9be4b066940329693c.html.

- National Park Service/ Office of Communications. President Biden designates Amache National Historic Site as America’s newest national park. March 18, 2022. Available at: https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1207/amache-nhs-designation.htm.

- Schultz, C. M. Paper Planes: Art from Japanese American Internment Camps Author. Art in Print September – October 2015, Vol. 5, No. 3 (September – October 2015), pp. 22-26 Art in Print Review Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26350652.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content., |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).