1. Introduction

School physical education for the initiation of invasion sports is a privileged scenario for the promotion of physical activity [

1]. The Self-Determination Theory is a theory of human motivation and personality that emphasizes the importance of the individual's ability to self-regulate his or her behavior, that is, it understands that individuals are responsible for their actions and relates self-determined behaviors to the propensity to engage in a wide range of human activities [

2]. It comprises four mini-theories, including the Basic Psychological Needs (BPNs) Theory. The BPNs theory involves three basic needs for the individual to develop and thrive: (1) autonomy (i.e., the possibility of voluntary choice in one's own activities and goals through participation in the decision-making process); (2) perceived competence (i.e., the ability to participate and engage in activities, and the execution (effectiveness) of the activities to achieve goals and success); and (3) social relationships (i.e., the need to reinforce the feeling of acceptance and belonging to the community in which one lives) [

3].

Interventions based on the Self-Determination Theory could be useful in the process of promotion and adherence to, physical activity [

4]. Thus, the satisfaction of three BPNs by students or players leads to an increase in intrinsic motivation, the most self-determined regulation, which causes students or players to engage in a sport modality on their own initiative (e.g., involvement in a sport for pleasure, fun, etc.). However, the frustration of these BPNs leads to an increase in extrinsic motivation (e.g., involvement in a sport to obtain a reward or avoid punishment) or demotivation (which can lead to the abandonment of sport practice) [

5]. Therefore, the motivation generated by the sport practice is one of the reasons that lead students or players to get involved in, or on the contrary, to abandon the sport practice [

6]. In physical education, García-Ceberino, Gamero, Feu and Ibáñez [

1] report that the more competent the students feel in school soccer, the greater the degree of adherence shown by them. In turn, Lamoneda and Huertas-Delgado [

7] report that students perceive a lower satisfaction of the BPNs as they advance in level and educational stage, producing a decrease in sport practice. In this regard, physical education teachers have a decisive role in the promotion of sport and adherence in and out-of-schools [

8]. In has regard, it has been shown that the teacher's adoption of a controlling interpersonal style is closely related to less self-determined regulations of motivation, thus generating a negative environment conditioned by the students' lack of autonomy [

9].

In the field of Sports Pedagogy, there are different methods to teach invasion sports during physical education classes [

10]. Given its proven benefits, teachers should implement a game-centered approach that facilitates the enhancement of motor learning, technical skills and the development of the tactical cognition process of the sport in question, moving away from direct instruction excessively focused on teaching technical skills [

11]. Therefore, this approach focuses attention on the student through tasks that stimulate the intertwined development of technical skills and tactical awareness [

11]. Within the game-centered approaches, the Tactical Games Approach (TGA) [

12] is suitable for the teaching of invasion sports. The TGA is an adaptation of the Teaching Games for Understanding (precursor of the game-centered approach) [

13], and is characterized by the use of small-sided games to facilitate the understanding of the game [

12]. Small-sided games allow students or players to experiment and solve tactical problems by modifying or adapting the length of the field, the number of players and/or the rules of each selected game [

14]. Specific formative programs have been intentionally designed and validated for the teaching of invasion sports, such as soccer [

15,

16] and basketball [

17,

18,

19]. These programs are oriented to primary physical education and based on different methods: TGA and traditional direct instruction.

From a pedagogical perspective, in addition to the method applied, it is relevant to take into account the gender and initial experience of the students when planning sport teaching in physical education, since both factors influence the teaching-learning process when working with mixed and heterogeneous school groups. This fact has been demonstrated in previous research on soccer [

20,

21,

22] and basketball [

23,

24] in primary schools. However, most of the research related to the methodological aspect does not usually consider the effect of both factors.

The lack of interest of students in physical education classes during primary school is increasing [

25]. One of the reasons for this lack of interest/participation could be linked to the method applied by the teacher, which in turn should consider the heterogeneity of the group-classes. Therefore, this study aimed to analyze whether students' gender and sport experience, and teaching method influence the psychological variables (BPNs and adherence to sport) when teaching school soccer and basketball. Moreover, correlations between both psychological variables were calculated. We hypothesized that: (1) Boys would report higher BPNs satisfaction and adherence to sport than girls; (2) Experienced students would report higher BPNs satisfaction and adherence to sport than non-experienced students; (3) The BPNs would be correlated with the intention to practice physical activity (adherence to sport); and (4) The perceived competence is the need that would report the highest correlation with the degree of adherence to sport.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A quasi-experimental study was carried out [

26]. Different teaching programs on soccer [

15,

16] and basketball [

17,

18,

19] were applied in the primary schools. These programs lasted three months (April to June), with one or two sessions per week (11 practical sessions in total). The school authorities indicated the days when researchers could go to the schools. It was also a cross-sectional study [

26], as data collection took place on a specific day at the end of the teaching programs. The class-groups of the participating primary schools were not modified, thus maintaining the ecological validity of the study.

Despite the fact that the study did not require invasive measures to obtain the data, the University Ethics Committee approved its protocol [protocol code: 105/2022]. Authorization was also requested from the primary schools and the physical education teachers at these schools. Moreover, the school board within the school curriculum approved the implementation of the study.

2.2. Participants and Procedure

The study involved 165 fifth and sixth grade students (age, 11.27 ± 0.68 years old), including 78 boys (47.30%) and 87 girls (52.70%), from five Spanish public primary schools in the autonomous community of Extremadura. In this regard, a non-random convenience sample was used, since the samples were selected according to two aspects: attendance at the schools where the academic authorities authorized their participation, and the proximity of the researchers’ residence to these schools (about 30 kilometers). The class-groups in the Spanish educational system are mixed and heterogeneous.

The inclusion criteria for participation in the study were: (1) the parents/legal guardians had to have signed an informed consent; (2) participants had to have attended at least 80% of the sessions; and (3) they had to have responded adequately (i.e., all items) to the instruments.

Information on the schools and class-groups participating in this study are shown in

Table 1, clarifying the professional and the teaching method used with each school and class-group.

The soccer [

15,

16] and basketball [

17,

18,

19] programs taught by researchers from outside the school, based on the TGA and DI methods (

Table 1), were specifically designed for teaching these invasion sports in physical education. In addition, they were validated by an expert panel with excellent content validity and internal consistency values. For each invasion sport, the programs differed in method (TGA/DI), but they were similar in specific content and game phases. In turn, the didactic units designed by the in-service teachers were based on a mixed method, closer to the DI method.

The choice of the class-groups to participate in each formative program/didactic unit was randomly selected. Both invasion sports contain common tactical principles, among others: maintaining possession of the ball or the advance towards the opponent's goal [

27].

At the end of the application of the teaching programs and didactic units in the different schools, the students answered two instruments, in the Spanish version adapted to physical education: (1) the scale for the Measurement of Basic Psychological Needs in Physical Exercise (four items for each need) [

28]; and (2) the Measure of Intention to be Physically Active (five items) [

29]. Both instruments were answered using a Likert-type scale from one to five points, with one = strongly disagree and five = strongly agree. The approximate response time was 25-30 minutes. The main researchers were present to explain the instruments and answer any questions.

Finally, once all the data were collected, they were exported to the statistical software for descriptive and inferential analysis.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data were calculated, using the mean and standard deviation, to characterize students' scores on the BPNs and the degree of adherence to sport.

The data presented a non-normal distribution, indicating the use of non-parametric tests. The students' scores on the BPNs and the degree of sport adherence were compared, according to gender and sport experience, using the Mann-Whitney U test (two categories); and according to teaching method, using the Kruskall-Wallis H test (three categories) [

30]. Furthermore, effect size was calculated using Rosenthal's r formula for the Mann-Whitney U test and the Epsilon-squared coefficient (

E2R) for the Kruskall-Wallis H test [

31,

32].

A regression analysis (structural equation model) was also calculated to verify the predictive capacity of the BPNs for the intention to practice physical activity (adherence to sport).

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS, version 27 (IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Differences were considered significant when p ≤ 0.05.

2.4. Endpoints

An acceptable model fit was obtained with the instruments grouped together (

Table 2), according to the values proposed by Hu and Bentler [

33]. The AMOS plugin (for SPSS 27.0 statistical software) was used for the analysis [

34]. In addition, Cronbach's alpha was good for both instruments (

α > 0.80) [

30,

35].

3. Results

There were significant differences in the autonomy and perceived competence needs according to the gender of the students (boys’ > girls’ scores). In addition, there were also significant differences according to the gender of the students (boys’ > girls’ scores) and sport experience (experienced students > inexperienced students) in adherence to sport.

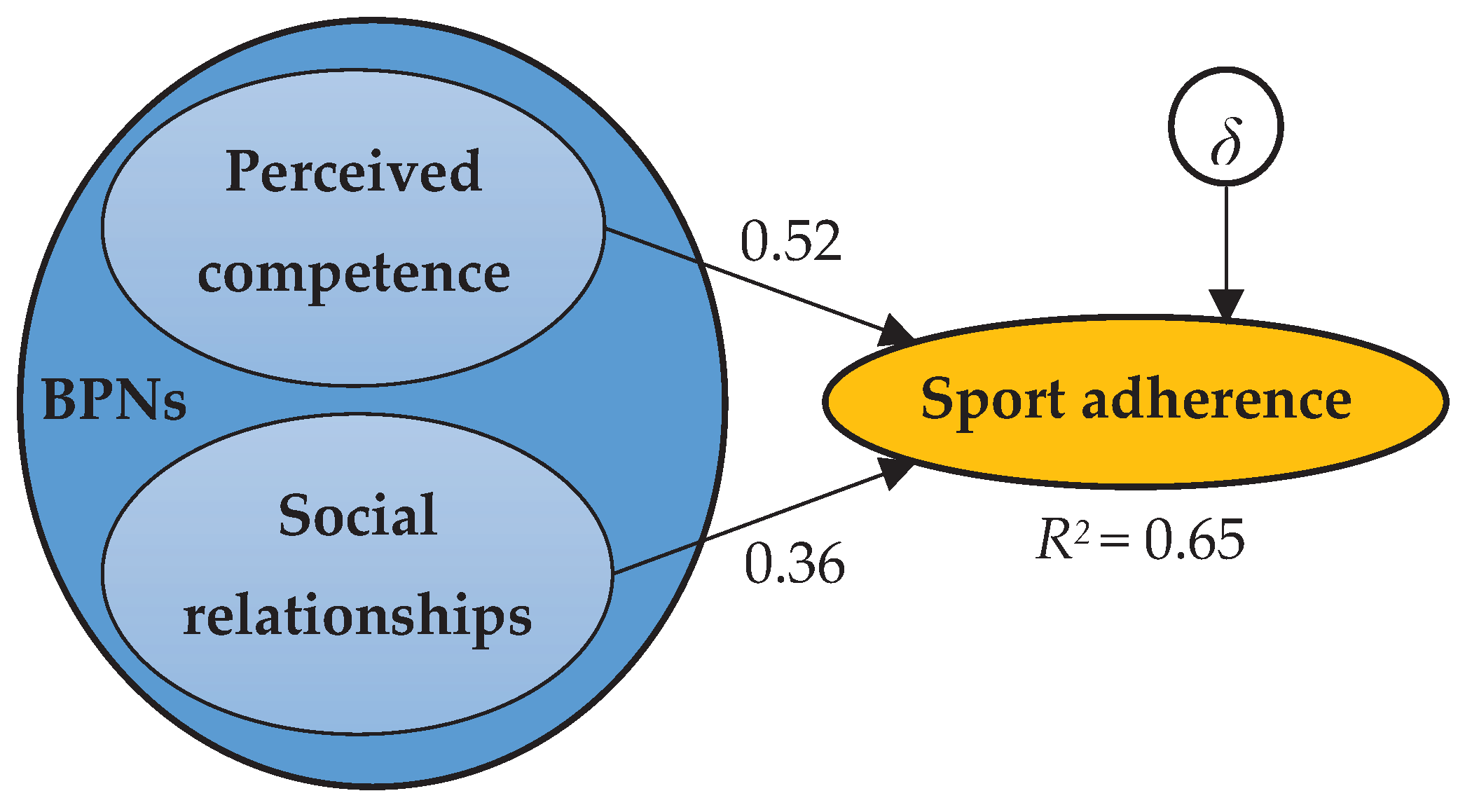

The proposed model shows that the perceived competence (

β = 0.52) and social relationships (

β = 0.36) correlate significantly with the sport adherence, obtaining a high coefficient of determination (

R2 = 0.65). Therefore, both needs predicts 65% commitment (

Figure 1) to sport adherence. The perceived competence is the main predictor factor. This percentage of commitment is reported by eliminating the autonomy need from the model because it shows a low correlation with sport adherence.

4. Discussion

The satisfaction of the BPNs increases students’ intention to be physically active [

36]. The heterogeneity of physical education classes in the Spanish educational system could mean that BPNs satisfaction is not perceived equally within the group of students. The purpose of this study was to analyze whether students' gender and experience in sport, and teaching method influence the various psychological variables (BPNs and sport adherence) when teaching school soccer and basketball. In addition, correlations between both psychological variables were calculated. The main results showed that there were significant differences in the needs for autonomy and perceived competence according to the students’ gender (boys > girls). Moreover, there were also significant differences according to the students’ gender (boys > girls) and sport experience (experienced students > inexperienced students) in sport adherence. Therefore, hypotheses 1 and 2 were partially accepted because there were no significant differences in all needs. On the other hand, the perceived competence and social relationships predicted 65% of adherence to sport, with the perceived competence as the main predictor. For these reasons, hypothesis 3 was partially accepted since autonomy showed a low correlation, and hypothesis 4 was fully accepted.

The participating boys reported greater autonomy, perceived competence and sport adherence in the invasion sports of soccer and basketball. In this regard, García-Ceberino, Gamero, Feu and Ibáñez [

1] reported that gender influenced perceived competence and students' intentionality to continue playing soccer in and out-of-school, in favor of boys. Gender-based analysis in another study [

37] reported higher BPNs satisfaction and higher intention to be physically active associated with boys (physical education students). Likewise, Gutierrez and García-López [

38] reported stereotypical participation, mainly in invasion sports, with girls being relegated to a spectator role. In contrast, Fernández-Hernández

, et al. [

39] reported no significant differences in satisfaction with the three BPNs or in the intention to be physically active according to the gender of the primary students.

Experienced students reported greater sport adherence in the invasion sports of soccer and basketball; however, there were no significant differences in three BPNs. A previous study [

1] reported that the initial experience influenced the students’ interest in continuing to play soccer in and out-of-school, but it did not influence their perceived competence. On the contrary, Heredia-León

, et al. [

40] reported that students who participated in extracurricular activities (i.e., out-of-school) were associated with self-determined profiles.

Rodríguez

, et al. [

41] noted the importance of taking into account the technical differences and motor condition of each student in physical education classes. In addition, adolescents girls reported greater barriers to physical activity practice compared to their boy classmates [

42]. Based on our results, physical education teachers should promote more self-determined regulations during the teaching-learning of school soccer and basketball, with especial attention on girls and inexperienced students.

As in the study developed by García-Ceberino, Gamero, Feu and Ibáñez [

1], on school soccer, there were no significant differences in the psychological variables studied according to the teaching method. In physical education, the role of the teacher has been shown to be determinant in students' satisfaction of BPNs [

43]. The teacher can condition students’ behavior through the method employed, creating an environment that generates greater motivation and self-determined regulation. In this regard, Contreras

, et al. [

44] reported that controlling methods focused on technical skills, as opposed to methods focused on understanding the game (e.g., the TGA), lead to lower motivation levels in students. Therefore, it is necessary to encourage students' motivation through attractive games (tactical problems) that generate active participation, fun and decision making, in order to obtain significant learning.

The model proposed in our study showed that perceived competence and social relationships were significantly and highly correlated with adherence to the soccer and basketball sports. A previous study [

37] also reported correlations between the BPNs satisfaction and the intention to be physically active in line with Self-Determination Theory. In addition, perceived competence was the strongest predictor of adherence to sport in this study. In this regard, Lamoneda and Huertas-Delgado [

7] indicated that, of the BPNs, perceived competence was also the most positively predictive of physical activity. A previous study, on school soccer [

1], reported that the more competent students feel, the greater their adherence to this sport. In a study with adolescents [

45], perceived competence was significantly associated with their participation in organized sports. Therefore, interventions based on Self-Determination Theory, supported by BPNs, could be a useful didactic strategy to motivate primary students to practice physical activity in other contexts.

Among the limitations of this study, it should be noted that the sport type and the educational stage of the students could cause the results to vary. Therefore, these results cannot be generalized to sports that do not have the same internal logic as soccer and basketball (e.g., individual sports) nor to middle school or high school. The findings reported the importance of satisfying the BPNs, especially perceived competence, to improve participation rates in invasion sports with health benefits (active lifestyle). In turn, Fernández-Espínola, Almagro, Tamayo-Fajardo, Paramio-Pérez and Saénz-López [

4] indicated that the involvement of families could also influence the promotion of physical activity in children and adolescents, therefore, this should be taken into account in future research.

5. Conclusions

The results of the study indicate that interventions based on Self-Determination Theory, supported by the BPNs, are necessary to motivate primary school students to practice physical activity in different contexts. In this regard, it is important that students feel competent in the sport in question, in order to increase their intention to be physically active. On the other hand, the heterogeneity of physical education classes is a factor to take into account when planning the teaching of soccer and basketball sports, paying special attention to girls and inexperienced students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.G.-C. and S.F.; methodology, J.M.G.-C. and S.F.; formal analysis, J.M.G.-C. and S.F.; investigation, J.M.G.-C., S.F., M.G.G. and S.J.I.; data curation, S.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.G.-C.; writing—review and editing, S.F., M.G.G. and S.J.I.; visualization, S.F., M.G.G. and S.J.I.; supervision, S.F. and S.J.I.; funding acquisition, S.J.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been partially subsidized by the Aid for Research Groups (GR21149) from the Regional Government of Extremadura (Department of Economy, Science and Digital Agenda), with a contribution from the European Union from the European Funds for Regional Development. The author J.M.G.-C. was supported by a grant from the Universities Ministry of Spain and the European Union (NextGenerationUE) “Ayuda del Programa de Recualificación del Sistema Universitario Español, Modalidad de ayudas Margarita Salas para la formación de jóvenes doctores” (MS-01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of the University of Extremadura (approval number: 105/2022; 29 June 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians of the students who were involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the academic authorities of the schools, the physical education teachers and the students for their participation in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Gamero, M.G.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. La percepción de la competencia en fútbol como indicador de la intencionalidad de los estudiantes de ser físicamente activos. e-Balonamo com 2021, 17, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior; Plenum Press: New York and London, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Espínola, C.; Almagro, B.J.; Tamayo-Fajardo, J.A.; Paramio-Pérez, G.; Saénz-López, P. Effects of Interventions Based on Achievement Goals and Self-Determination Theories on the Intention to Be Physically Active of Physical Education Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Soenens, B. Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion 2020, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garn, A.C.; Cothran, D.J. The fun factor in physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 2006, 25, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoneda, J.; Huertas-Delgado, F.J. Necesidades psicológicas básicas, organización deportiva y niveles de actividad física en escolares. Revista de Psicología del Deporte 2019, 28, 115–124. [Google Scholar]

- da Costa, L.C.A.; Passos, P.C.B.; de Souza, V.F.M.; Vieira, L.F. Educação física e esportes: Motivando para a prática cotidiana escolar. Movimento 2017, 23, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granero-Gallegos, A.; Jorquera-Jordán, J.; Carrasco-Poyatos, M.; Gómez-López, M. Controlling interpersonal style and motivation in Physical Education: A systematic review. e-Balonmano com 2022, 18, 257–270. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Pueyo, Á.; Hortigüela-Alcalá, D.; Fernández-Río, J. Los modelos pedagógicos en educación física: qué, cómo, por qué y para qué; Servicio de Publicaciones: Universidad de León, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R.; Farias, C.; Ramos, A.; Mesquita, I. Implementation of Game-Centered Approaches in Physical Education: A Systematic Review. Journal of Physical Education and Sport 2021, 21, 3246–3259. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, S.; Mitchell, S.A.; Oslin, J.; Griffin, L.L. Teaching sport concepts and skills: A tactical games approach; Human Kinetics Publishers: Champaign, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bunker, D.; Thorpe, R. A model for the teaching of games in secondary schools. Bulletin of Physical Education 1982, 18, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Espínola, C.; Abad-Robles, M.T.; Giménez, F.J. Small-sided games as a methodological resource for team sports teaching: A systematic review 2020, 17, 1884–1884. [CrossRef]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. Comparative Study of Two Intervention Programmes for Teaching Soccer to School-Age Students. Sports 2019, 7, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Antúnez, A.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. Validación de dos programas de intervención para la enseñanza del fútbol escolar / Validation of Two Intervention Programs for Teaching School Soccer. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de la Actividad Física y el Deporte 2020, 20, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Espinosa, S.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Feu, S. Design of two basketball teaching programs in two different teaching methods. e-Balonmano com 2017, 13, 131–152. [Google Scholar]

- González-Espinosa, S.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Feu, S.; Galatti, L.R. Programas de intervención para la enseñanza deportiva en el contexto escolar, PETB y PEAB: Estudio preliminar. Retos. Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación 2017, 31, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamero, M.G.; García-Ceberino, J.M.; Rodriguez-Rocha, J.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Feu, S. Estudio de tres programas de intervención para la enseñanza del baloncesto en edad escolar. Un estudio de casos. e-Balonmano com 2022, 18, 127–148. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Gamero, M.G.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. Experience as a Determinant of Declarative and Procedural Knowledge in School Football. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Gamero, M.G.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. Differences in Technical and Tactical Learning of Football According to the Teaching Methodology: A Study in an Educational Context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Antúnez, A.; Feu, S.; Ibáñez, S.J. Quantification of Internal and External Load in School Football According to Gender and Teaching Methodology. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamero, M.G.; García-Ceberino, J.M.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Feu, S. Analysis of Declarative and Procedural Knowledge According to Teaching Method and Experience in School Basketball. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamero, M.G.; García-Ceberino, J.M.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Feu, S. Influence of the Pedagogical Model and Experience on the Internal and External Task Load in School Basketball. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 11854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aniszewski, E.; Henrique, J.; Oliveira, A.J.d.; Alvernaz, A.; Vianna, J.A. (A)Motivation in physical education classes and satisfaction of competence, autonomy and relatedness. Journal of Physical Education 2019, 30, e3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ato, M.; López-García, J.J.; Benavente, A. Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de Psicología 2013, 29, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, C. La Enseñanza de los Juegos Deportivos Colectivos; Hispano Europea: Barcelona, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J.A.; González-Cutre, D.; Chillón, M.; Parra, N. Adaptación a la educación física de la escala de las necesidades psicológicas básicas en el ejercicio. Revista Mexicana de Psicología 2008, 25, 295–303. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J.A.; Moreno, R.; Cervelló, E. El autoconcepto físico como predictor de la intención de ser físicamente activo. Psicología y Salud 2007, 17, 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering statistics using SPSS statistics, 4th ed.; Sage Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect Size Estimates: Current Use, Calculations, and Interpretation. Journal of Experimental Psychology General 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, M.; Tomczak, E. The need to report effect size estimates revisited. An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. TRENDS in Sport Sciences 2014, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, J.; Lim, J. Model Fit Measures (AMOS Plugin). Gaskination’s StatWiki: 2016.

- Cronbach, L.J. Essentials of psychological testing, 5th ed.; Harper & Row: New York, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas-Campos, R.; Fernández-Bustos, J.G.; González-Cutre, D.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Need satisfaction and need thwarting in physical education and intention to be physically active. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Espínola, C.; Jorquera-Jordán, J.; Paramio-Pérez, G.; Almagro, B.J. Psychological needs, motivation and intent to be physically active of the physical education student. Journal of Sport and Health Research 2021, 13, 467–480. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, D.; García-López, L.M. Gender differences in game behaviour in invasion games. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy 2012, 17, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Hernández, A.; Manzano-Sánchez, D.; Jiménez-Parra, J.F.; Valero-Valenzuela, A. Analysis of differences according to gender in the level of physical activity, motivation, psychological needs and responsibility in Primary Education. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise 2021, 16, S580–S589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia-León, D.A.; Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Gómez-Marmol, A.; Manzano-Sánchez, D. Motivational Profiles in Physical Education: Differences at the Psychosocial, Gender, Age and Extracurricular Sports Practice Levels. Children 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Á.; Chicaiza, L.; Cusme, A. Metodologías emergentes para la enseñanza de la Educación Física (Revisión). Revista Científica Olimpia 2022, 19, 98–115. [Google Scholar]

- Macarro-Sillero, A.; Carlos-Vivas, J.; Barrios-Fernández, S.; Mendoza-Muñoz, M.; Pastor-Cisneros, R.; Franco-García, J.M. Relación entre las barreras para la práctica deportiva y la condición física en adolescentes extremeños desde una perspectiva de género. e-Motion: Revista de Educación, Motricidad e Investigación 2021, 17, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro-Suero, S.; Almagro, B.J.; Sáenz-López, P.; Carmona-Márquez, J. Perceived novelty support and psychological needs satisfaction in physical education. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health 2020, 17, 4169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, O.R.; de la Torre, E.; Velázquez, R. Iniciación deportiva; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Spruijtenburg, G.E.; van Abswoude, F.; Platvoet, S.; de Niet, M.; Bekhuis, H.; Steenbergen, B. Factors Related to Adolescents’ Participation in Organized Sports. International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health 2022, 19, 15872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).