1. Introduction

Community-based medical education (CBME) is a type of medical education that focuses on providing students with hands-on experience in the community. This type of education emphasizes learning from and engaging with patients, families, and other community members. It also encourages students to understand the social determinants of health, such as poverty, racism, and access to healthcare. Community-based medical education can occur in various settings, including hospitals, clinics, schools, and community centers [

1]. CBME is an approach that emphasizes the importance of involving local communities in the educational process [

2]. It is a collaborative effort between schools, families, and community members to create a learning environment that is relevant, meaningful, and responsive to the community's needs [

3].

CBME recognizes that education is about academic achievement and developing social skills, cultural awareness, and civic responsibility [

4]. CBME aims to empower individuals and communities to actively shape their educational experiences and outcomes [

5]. This approach effectively improves student engagement, academic performance, and well-being [

6].

Primary healthcare physicians are crucial in community-based medical education [

7]. They are the first point of contact for patients seeking medical care and are responsible for providing comprehensive and continuous care to their patients. As such, they have a unique perspective on the health needs of their community and can provide valuable insights into the development of community-based medical education programs [

8].

One of the primary roles of primary healthcare physicians in community-based medical education is to serve as mentors and preceptors for medical students and residents [

9]. They can guide and support these learners as they develop their clinical skills and knowledge. This includes teaching them how to conduct patient assessments, diagnose illnesses, develop treatment plans, and communicate effectively with patients [

9].

In addition to serving as mentors, primary healthcare physicians can contribute to developing community-based medical education programs by sharing their knowledge and expertise with educators [

10]. They can provide insights into the health needs of their community, identify areas where additional training may be needed, and help educators design relevant and effective programs [

11].

Primary healthcare physicians can be vital in promoting community engagement among medical learners [

12]. By involving learners in community outreach activities such as health fairs or vaccination clinics, they can help them develop a deeper understanding of the social determinants of health and the importance of working collaboratively with other healthcare providers [

13].

Primary healthcare physicians are essential in community-based medical education [

14]. Through their mentorship, expertise, and engagement with learners and educators alike, they can help ensure that future generations of healthcare providers are well-prepared to meet the needs of their communities [

15].

The primary health care system in Saudi Arabia is an established and effective system that provides opportunities for PHPs to participate in CBME activities and greater integration with medical school. CBME can build partnerships between the university, service providers, and community and the student’s learning and service activities, positively influencing community health and preparing students to care for people in rural communities. In this context, this study aimed to explore the awareness and engagement of PHPs toward community-based medical education and investigate the factors influencing their participation in the CBME organized by the College of Medicine, University of Bisha.

2. Materials and Methods

Study design: This mixed study was conducted in two phases from June 2022 to December 2022. In the first phase, a qualitative study was conducted using semi-structured interviews with PHPs, and thematic analysis related to their awareness and engagement in CBME. In the second phase, a quantitative survey was conducted among the participants' pre- and post-training programs.

Participants and sampling: All physicians working in PHC centers in Bisha province were invited to participate in the study conducted University of Bisha (n = 72), identifying the predictors of primary healthcare physicians towards engagement in community-based medical education. They work in 33 PHC centers with clinical or clinical duties and administrative tasks. They provide general practice, family medicine, obstetrics, and Pediatrics services.

The sample size was determined using a power analysis based on the estimated population size of primary healthcare physicians working in community health centers. A random sampling technique was used to select participants from different PHCs.

Training workshops: We designed a program of three serial workshops about community-based medical education. The assessment was done at the beginning of the first workshop and the end of the third workshop. In between, a hotline is active to respond to their questions.

Key points from the workshop emphasized the importance of community-based medical education for training primary healthcare physicians to engage with their communities and commit to improving patient outcomes. They were asked to complete the questionnaire containing the same items in pre- and post-evaluation. The main areas covered in the training program included:

Introduction to CBME

Understanding the community:

Engaging with the community:

Curriculum development:

Faculty development: how to train faculty members to teach in a CBME program.

Evaluation and assessment: how to evaluate and assess the effectiveness of a CBME.

Sustainability focuses on how to ensure that program is sustainable over time.

Data collection: The quantitative data collection using a self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire was distributed to participants through their workplace or by email. Participants have the option to complete the questionnaire online or on paper.

The questionnaire includes the following sections:

1. The sociodemographic data and general characteristics of the study population, including (age, nationality, professional position, gender, years of experience, place of work, and Academic experience)

2. Awareness towards CBME, including (the influence of CBME on the student selection for rural placement, CBME as an additional opportunity for students going on rural placement, and to improve the interest of graduates to work in the rural area)

3. PHC physicians intend to engage in the CBME program at the University of Bisha and be willing to participate in training medical students at the University of Bisha.

Qualitative data collection was collected by using open questions survey pre-training programs.to provide a comprehensive understanding of how community-based medical education programs impact primary healthcare physicians' awareness and engagement levels.

Data Analysis: The quantitative data were analyzed using Stata/ BE 17.0 Stata Corp LLC. Descriptive statistics were summarized. Logistic regression analysis identified predictors of primary healthcare physicians' engagement in community-based medical education.

By a thematic analysis approach, the qualitative analysis identified three main themes related to PHPs' awareness and engagement in CBME: (1) lack of knowledge about CBME; (2) limited involvement in CBME activities; and (3) perceived benefits of engaging in CBME.

3. Results

In this study, 72 PHC physicians were enrolled and participated in a comprehensive educational program. More than half were under 40 (54.2%), and most were non-Saudi (91.7%). Most were female (68.1%) and worked in urban settings (66.7%). Regarding their work experience, we found that more than half have ten years of experience (63.9%). In contrast, most (88.9%) perform purely clinical duties, and 83.3% have no academic experience (

Table 1).

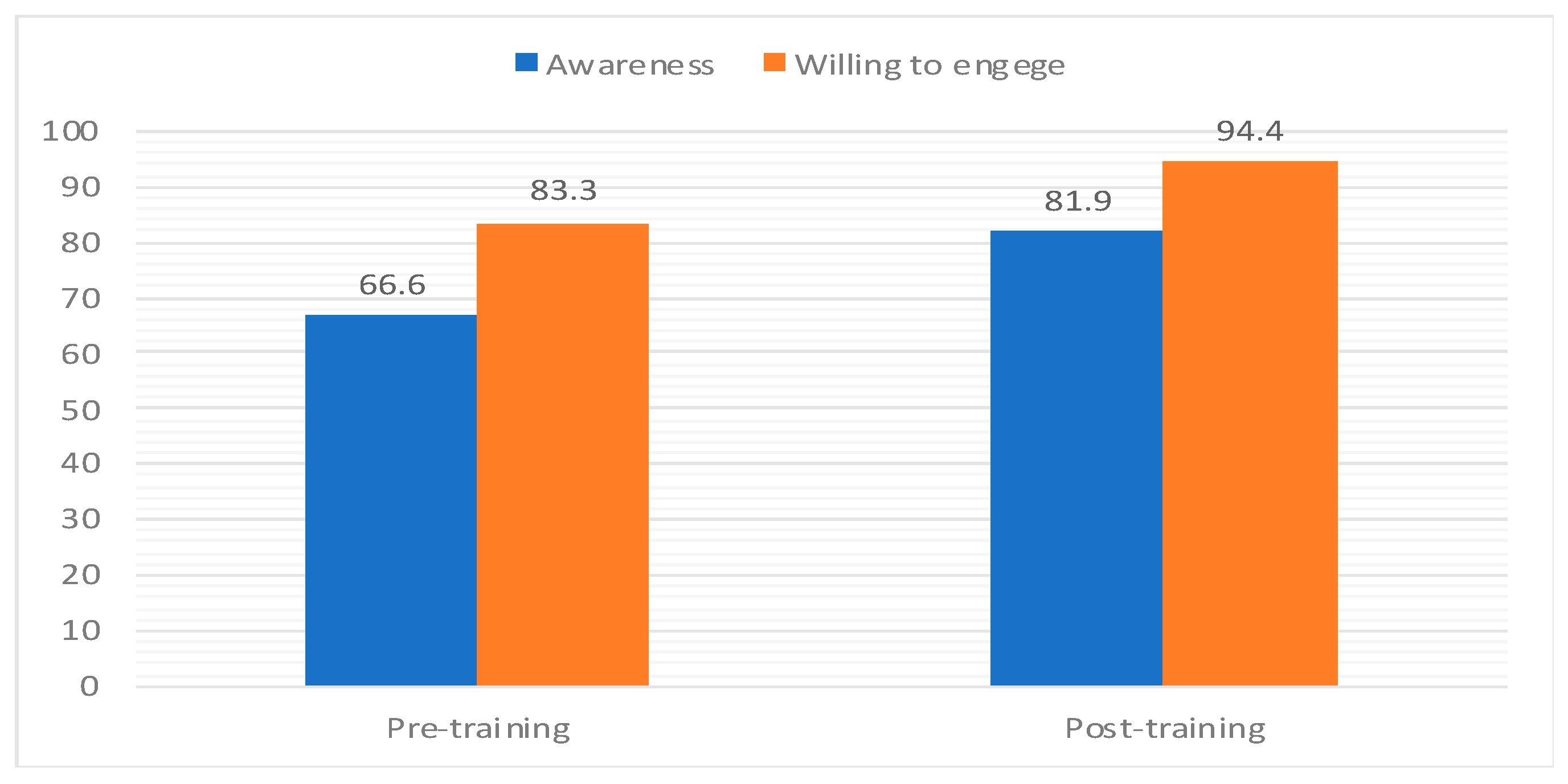

The training program influences PHC physicians' willingness to participate in community-based medical education activities at the College of Medicine, University of Bisha. The proportion of PHC physicians who desired to engage in CBME increased from 83.3% to 94.4% (p-value = 0.001). Age 40 (p-value = 0.05), female gender (p-value = 0.002), pure clinical duties (p-value = 0.001), working in urban settings (p-value = 0.001), and academic experience (p-value = 0.001) were significant predictors of willingness. However, nationality and years of experience do not demonstrate substantial correlations (p-values greater than 0.05), but their willingness is positively reflected and increased after the training program (

Table 2). The training program's impact on the awareness and desire to engage PHC physicians in the CBME is explained in (

Figure 1).

Considering the importance of awareness in CBME engagement, most PHC physicians have an acceptable level of understanding, which increased substantially (p-value = 0.03) from 66.6% to 81.9% after the training. The majority (66.6% vs. 87.5%) of PHC physicians reported that students' community involvement influences their decision to choose a rural placement after training (p-value = 0.001). Most participants were aware that the CBME encouraged students to train in PHC and rural institutions (p-value 0.001). In addition, most participants knew that CBME offers pre- and post-training opportunities for students and graduates to work in rural placements (86.1%, 97.2%, and 75%, 93%). (

Table 3).

Logistic regression models were used to identify factors that positively predict the PHC physicians willing to engage in CBME activities at the University of Bisha. Binary logistic analysis revealed that non-Saudi physicians are 10.33 times more likely to be associated with willingness to be a part of CBME than Saudi (p-value=0.001, 95% CI=4.47-23.88). However, the willingness to participate is significantly high among physicians with work experience of more than ten years. (OR =1.61, p-value=0.05, 95 % CI=0.99-2.63). Professions with pure clinical duties versus clinical and administration showed a highly significant welling to participate in CBME (OR= 7.5) more time (p-value=0.001, 95 % CI=3.586-15.68). PHC physicians with academic experiences were more willing to participate in CBME than those with non-academic experience ((OR =0.21, p-value=0.001, 95 % CI=0.11-0.39). Age and place of work are not strong predictors for detection of the willingness to participate in CBME ((OR =0.94, p-value=0.08, 95 % CI=0.58-1.51), ((OR =0.14, p-value=0.1, 95 % CI=0.01-1.5), respectively. More details of logistic regression models showed in (

Table 4).

The qualitative analysis identified that PHPs were found to have a positive attitude toward CBME. They believed it was an effective way to improve the quality of healthcare services in the community and enhance their professional development. The physicians also expressed a willingness to participate in community-based medical education activities, such as teaching and mentoring medical students and residents. The predictors of primary healthcare physicians' engagement in community-based medical education included their experience level, workload, availability of resources, and support from their organizations. Physicians with more experience were more likely to engage in community-based medical education activities, while those with heavier workloads were less likely to do so. Support from their organizations, including recognition and incentives for participation, was crucial for motivating physicians to engage in community-based medical education. However, efforts are needed to address the barriers that prevent them from engaging fully in these activities, including workload and resource constraints. Organizations should also provide support and incentives for physicians who engage in CBME to ensure its sustainability over time (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

In Saudi Arabia, primary health physicians play a crucial role in the healthcare system by providing direct care services to individuals and families. They are often the first point of contact for patients seeking medical attention. They are responsible for diagnosing and treating common illnesses, managing chronic conditions, and promoting preventive health measures. CBME approach aims to prepare medical students for the challenges they will face in their future careers by providing them with hands-on experience working with diverse patient populations and addressing social determinants of health. In this discussion, we will explore the awareness and engagement in addition to the influencing factors of PHC physicians toward CBME. Further in-depth analysis will be discus on qualitative factors of CBME in a newly established medical school in Saudi Arabia.

In this study, most PHC physicians are adequately aware of CBME, which increased following training. This finding is inconsistent with (Bansal A et al. 2022), indicating that the activity could significantly raise primary healthcare physicians' awareness of community-based medical education [

16]. (Reis et al. 2022) revealed that the movement can play a crucial role in increasing the awareness of primary healthcare physicians toward community-based medical education [

17]. Our training program provides the participants with the necessary skills and knowledge, aiming to help improve patient healthcare outcomes and promote more effective collaboration between providers and communities. This is the alliance with the vision of the University of Bisha as a medical college established in rural service areas in Saudi Arabia.

In this study, the participants reported that the involvement of students in their communities influences their decision to choose a rural placement, and community-based medical education can provide opportunities for students and graduates to work in rural stations. This finding is consistent with a recent study from the USA which indicated that the involvement of students in their communities could significantly impact their decision to choose a rural placement [

18]. Also, another study from Australia showed that community-based medical education programs provide opportunities for students and graduates to work in rural stations [

19]. When students engage with the local community, they better understand rural populations' healthcare needs and challenges. This exposure can help them develop a sense of purpose and commitment to serving these underserved communities. Our programs offer hands-on training and experience in rural healthcare settings, which can help students develop the skills and knowledge needed to provide quality care in these areas. Besides that, community-based medical education programs often offer mentorship and support for students as they navigate the challenges of working in rural settings.

This study showed that the training program increased the willingness of PHC physicians to participate in community-based medical education activities conducted by the College of Medicine at the University of Bisha. These findings, consistent with the study, indicated that the engagement of primary healthcare in community-based medical education is crucial for developing competent and compassionate healthcare professionals [

20]. Ndambo, 2022 showed that engaging primary healthcare providers in community-based medical education also benefits the providers themselves [

21]. The impact of training in increasing the engagement of primary healthcare in community-based medical education was confirmed by [

22,

23,

24]. The concentration of primary healthcare in community-based medical education is essential for building a robust healthcare workforce equipped to meet diverse populations' needs. Medical schools and primary healthcare providers must collaborate to create meaningful learning experiences that benefit students and patients.

Significant predictors of willingness were age over 40, female gender, pure clinical duties, working in urban settings, and academic experience. However, nationality and years of experience did not have significant correlations. These findings have been highlighted in the literature, and several important factors can influence primary healthcare physicians' willingness to participate in community-based medical education [

24,

25]. We are in the College of Medicine, University of Bisha. We will consider understanding these factors and work towards addressing them to encourage more primary healthcare physicians to participate in community-based medical education programs.

An in-depth qualitative analysis was highlighted to understand the factors that impact the interest and motivation of primary healthcare physicians towards more engagement in CBME activities at the University of Bisha. It was indicated that physicians' interest benefits their professional development, patient care, effective community engagement, receiving institutional support, and having enough spare time to engage in CBME.

This study consisted of findings that revealed several factors that impact the interest of primary health physicians in community-based education [

26,

27]. This qualitative approach involved in-depth interviews with primary health physicians with community-based education experience. We can use these findings to understand better the environment that can help adopt CBME at the University of Bisha. Physicians who participate in community-based medical education programs also benefit from the experience. They have the opportunity to mentor and teach the next generation of healthcare providers, which can be a rewarding experience. They may gain new insights into the healthcare needs of their community and develop new strategies for addressing those needs.

This study indicated that physicians firmly committed to the local community are more likely to participate in community-based medical education programs. The relationship between physicians and a strong commitment to their local community is extensively evaluated in the literature [

28,

29,

30,

31], which indicates that they are more likely to participate in community-based medical education programs because they see it as an opportunity to positively impact the health of their neighbors and build stronger connections within their professional network. The CBME programs at the University of Bisha provide opportunities for medical students and residents to gain hands-on experience in community settings, such as clinics, hospitals, and community health centers. By working alongside experienced physicians in these settings, students can learn about the local population's unique health needs and challenges and develop critical clinical skills.

We argued that involving students in their communities and providing community-based medical education opportunities can help address the shortage of healthcare professionals in rural areas. By fostering a sense of connection and commitment to these communities, we can encourage more students to choose rural placements and ultimately improve access to healthcare for underserved populations. The curriculum of the College of Medicine, University of Bisha, will be updated according to the community-based medical education curriculum. The current situation around Bisha University is suitable for students to train in their community settings. The finding of this research will help us in the curriculum review and update of the College of Medicine, Saudi Arabia. Curriculum update focuses on at least one of the components of community-based medical education (CBME); primary healthcare centers, families, and rural hospitals.

5. Conclusions

The study findings highlighted the importance of increased awareness and the factors that enhance PHPs' engagement in CBME. This positive perspective of the PHPs helps build effective partnerships and facilitates the extension of the curriculum to apply CBME. It also emphasizes the need to address the barriers that prevent PHPs from engaging in CBME activities. Future research should focus on developing strategies to increase PHPs' engagement in CBME and evaluating the impact of such strategies on medical education and healthcare outcomes.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception, data collection and analysis, statistical analysis, written review, copyediting, and L.V. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“This research received no external funding”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the College of Medicine, University of Bisha, Saudi Arabia.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the contributions of the PHC physicians to the success of the program and the College of Medicine of Bisha University for their logistical support. We'd also like to thank the community-based medical education unit for their technical help.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- D’Adamo, C.R.; Workman, K.; Barnabic, C.; Retener, N.; Siaton, B.; Piedrahita, G.; Bowden, B.; Norman, N.; Berman, B.M. Culinary medicine training in core medical school curriculum improved medical student nutrition knowledge and confidence in providing nutrition counseling. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2022, 16, 740–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claramita, M.; Setiawati, E.P.; Kristina, T.N.; Emilia, O.; Van Der Vleuten, C. Community-based educational design for undergraduate medical education: a grounded theory study. BMC medical education. 2019, 19, 1–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagatpatan Jr CP, Valdezco JA, Lauron JD. Teaching the affective domain in community-based medical education: A scoping review. Medical teacher. 2020, 42, 507–14. [CrossRef]

- Majewska, IA. Teaching global competence: Challenges and opportunities. College Teaching. 2022, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacoby, Y.; Girash, J.; Parkes, D.C. Empowering First-Year Computer Science Ph. D. Students to Create a Culture that Values Community and Mental Health. InProceedings of the 54th ACM Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education V. 1 2023 Mar 2 (pp. 694-700). [CrossRef]

- Patrick, L.E.; Duggan, J.M.; Dizney, L. Integrating evidence-based teaching practices into the mammalogy classroom. Journal of Mammalogy. 2023, gyad011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunathilake, I.; Kristina, T.N. Curriculum Design of Community-Based Education, Toward Social Accountability of Health Profession Education. InChallenges and Opportunities in Health Professions Education: Perspectives in the Context of Cultural Diversity 2022, (pp. 87-109). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Gizaw, Z.; Astale, T.; Kassie, G.M. What improves access to primary healthcare services in rural communities? A systematic review. BMC Primary Care. 2022, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casola, A.R.; Cunningham, A.; Crittendon, D.; Kelly, S.; Sifri, R.; Arenson, C. Implementing and Evaluating a Fellowship for Community-Based Physicians and Physician Assistants: Leadership, Practice Transformation, and Precepting. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2022, 42, 144–7 DOI%3A%20101097/CEH0000000000000427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, S.; Kruger, W.H.; Walsh, C.M. Chronic diseases of lifestyle curriculum: Students’ perceptions in primary health care settings. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine. 2023, 15, 3775. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Yan, D.; Hu, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, D.; Wang, J. Comparison of attitudes toward the medical student-led community health education service to support chronic disease self-management among students, faculty and patients. BMC Medical Education. 2023, 23, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reath, J.; Lau, P.; Lo, W.; Trankle, S.; Brooks, M.; Shahab, Y.; Abbott, P. Strengthening learning and research in health equity–opportunities for university departments of primary health care and general practice. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2022 Nov 8. [CrossRef]

- Gunaldo, T.P.; Ankam, N.S.; Black, E.W.; Davis, A.H.; Mitchell, A.B.; Sanne, S.; Umland, E.M.; Blue, A.V. Sustaining large scale longitudinal interprofessional community-based health education experiences: Recommendations from three institutions. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice. 2022, 29, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblanc, P.; Occelli, P.; Etienne, J.; Rode, G.; Colin, C. Assessing the implementation of community-based learning in public health: a mixed methods approach. BMC Medical Education. 2022, 22, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, D.A.; Naccarato, T.T.; Philip, M.T.; Ploszay, V.K.; Winkler, J.; Sanchez-Ramirez, D.C.; Penner, J.L. Understanding student-run health initiatives in the context of community-based services: a concept analysis and proposed definitions. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health. 2022, 13:21501319221126293. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Greenley, S.; Mitchell, C.; Park, S.; Shearn, K.; Reeve, J. Optimising planned medical education strategies to develop learners' person-centredness: A realist review. Medical Education. 2022, 56, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, T. , Faria, I., Serra, H. et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing a continuing medical education intervention in a primary health care setting. BMC Health Serv Res 2022, 22, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowl, S.; Smith, R.A.; Brown, M.G. Rural college graduates: Who comes home? . Rural Sociology. 2022, 87, 303–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, C.E. , Green, E. and Freire, K. Effect of rural clinical placements on intention to practice and employment in rural Australia: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2022, 19, 5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Button, B.L.; Cheu, H.; Stroink, M.; Cameron, E. Exploring rural medical education: a study of Canadian key informants. Rural and Remote Health. 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndambo, M.K.; Munyaneza, F.; Aron, M.B.; et al. Qualitative assessment of community health workers’ perspective on their motivation in community-based primary health care in rural Malawi. BMC Health Serv Res 2022, 22, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweku, M.; Amu, H.; Awolu, A.; Adjuik, M.; Ayanore, M.A.; Manu, E.; Tarkang, E.E.; Komesuor, J.; Asalu, G.A.; Aku, F.Y.; Kugbey, N. Community-based health planning and services plus programme in Ghana: a qualitative study with stakeholders in two systems learning districts on improving the implementation of primary health care. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0226808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushamiri, I.; Belai, W.; Sacks, E.; Genberg, B.; Gupta, S.; Perry, H.B. Evidence on the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving HIV/AIDS outcomes for mothers and children in low-and middle-income countries: findings from a systematic review. Journal of global health. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, V.; Chetty, V.; Maddocks, S.; Chemane, N. Community-based primary healthcare training for physiotherapy: students’ perceptions of a learning platform. South African Journal of Physiotherapy. 2019, 75, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.Y.; Chuang, M.C.; Chen, I.P.; Yu, P.H. Primary drivers of willingness to continue to participate in community-based health screening for chronic diseases. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2019, 16, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booker, Q.S.; Austin, J.D.; Balasubramanian, B.A. Survey strategies to increase participant response rates in primary care research studies. Family Practice. 2021, 38, 699–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Findyartini, A.; Kambey, D.R.; Yusra, R.Y.; Timor, A.B.; Khairani, C.D.; Setyorini, D.; Soemantri, D. Interprofessional collaborative practice in primary healthcare settings in Indonesia: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice. 2019, 17, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotchoungchatchai, S.; Marshall, A.I.; Witthayapipopsakul, W.; Panichkriangkrai, W.; Patcharanarumol, W.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Primary health care and sustainable development goals. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2020, 98, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisa, R.; Omitogun, T.I. Awareness, knowledge, attitude and practice of adverse drug reaction reporting among health workers and patients in selected primary healthcare centres in Ibadan, southwestern Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res 2019, 19, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyhne, C.N.; Bjerrum, M.; Jørgensen, M.J. Person-centred care to prevent hospitalisations – a focus group study addressing the views of healthcare providers. BMC Health Serv Res 2022, 22, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwole, A.S.; Bettee, A.K.; Nganda, M.M.; Piotrowski, H.L.; Fapohunda, V.O.; Adejobi, J.B.; Soneye, I.Y.; Kafil-Emiola, M.A.; Soyinka, F.O.; Nebe, O.J.; Ekpo, U.F. A quality improvement approach in co-developing a primary healthcare package for raising awareness and managing female genital schistosomiasis in Nigeria and Liberia. International Health. 2023, 15 (Supplement_1), i30-42. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).