1. Introduction

Ecotourism is the most effective means of enhancing biodiversity preservation and lowering poverty in local communities in protected areas. This is because it makes use of a sizable labor force, attracts outside money for infrastructure development, and benefits from local expertise (Mbaiwa & Stronza, 2010). The same sources also emphasized how, if done well, ecotourism may be used as a pro-poor strategy for the rural poor communities that reside adjacent to the protected area. Yet, it is well acknowledged that the development of ecotourism does not always benefit the environment and local residents; in fact, ecotourism can occasionally have significant negative effects on the ecosystem and the socioeconomic situation (Mariam, 2015; Nor et al., 2018; Teshome et al., 2021).

One of the main reasons for the negative perception of local communities was the lack of participation by local communities. If they do not get involved with different ecotourism activities and benefit from them, local people in protected areas are more likely to have a negative attitude towards the development of ecotourism (Liu et al., 2012). For ecotourism to successfully develop in destination areas, it is crucial to understand the factors that affect local residents' participation in it and their perceptions of its effects (Wang et al., 2006). Since local communities' opinions about ecotourism are influenced by how tourism is perceived to affect their communities, both favorably and negatively, the study of park communities' attitudes toward tourism has been a significant topic of research in the field (Holladay & Ormsby, 2011; Xu et al., 2022).

Several research results recommended that the ecotourism industry in the destinations needs to be successfully planned, carried out, and focused on the community in terms of management, decision-making, and benefit-sharing methods. This is because ecotourism would negatively impact the viability of the local environment and the living conditions of the residents (Abuhay et al., 2019; Amogne, 2014; Pengwei & Linsheng, 2018). Integrated conservation and development projects (ICDP) and payment for ecosystem services (PES) programs are currently being employed to reduce the direct danger to biodiversity posed by the local population. These novel approaches acknowledge the trade-offs and connections between human livelihood and biodiversity conservation. In order to bring economic value to biodiversity, they emphasize incorporating local communities in conservation and using market tools. Using these approaches, it is suggested that poverty can be decreased and attitudes towards environmental awareness and conservation can be improved by giving local residents new opportunities for work or direct payment (Abdurahman et al., 2016; Bown, 2010; K et al., 2014; Reindrawati et al., 2022).

Few studies have been done in this context to date to examine and assess the factors influencing how ecotourism affects the local communities residing in and around the parks (Chamboko-Mpotaringa & Tichaawa, 2021; K et al., 2014; Kimengsi, 2015).The results of the current study will therefore help policymakers and decision-makers develop and put into action a strategy that would address the concerns of the park communities that reside in and around the park, achieve sustainable biodiversity conservation, and actualize environmentally friendly livelihood alternatives (Abukari & Mwalyosi, 2020; He et al., 2020; Salman et al., 2020). The aforementioned insights and the reviewed literature have revealed that the majority of studies on the livelihood impacts of ecotourism in the PAs of Ethiopia predominantly focused on the role that ecotourism plays in enhancing livelihoods while ignoring the impacts of ecotourism perceived by local communities.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were: (1) to assess the park communities’ perceptions of the economic, socio-cultural, and environmental impacts of ecotourism; (2) to identify the determinant factors that affect the local community’s perception of the impact of ecotourism; and (3) to examine the relationship between socio-demographic variables and participation in ecotourism activities in SMNP, North Gondar, Ethiopia.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods approach to obtain both qualitative and quantitative data. This approach was selected because of the nature of the topic under study and the stakeholders involved. By combining data from different sources, the researchers aimed to triangulate the findings, increase the validity of the conclusions, and overcome the limitations of using a single approach. The study used a sequential embedded mixed method, where qualitative data was used to support the development of survey instruments and to follow up on and explain quantitative results.

A multi-stage probability and non-probability selection technique was used to select the study area and participants. The five districts bordering the SMNP were chosen, and three woredas (districts) were randomly selected from them. Three kebeles(villages) were then randomly chosen from each woreda(district). The sample size of 397 households was determined using the Yemane formula, and households were randomly selected using systematic and proportional random selection. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected using a questionnaire, interviews, focus groups, observations, and secondary data sources. The questionnaire included open-ended, multiple-choice, yes-or-no, and rating-scale questions and was used to measure community support for ecotourism and awareness of it in the study area. Interviews and focus groups were used to gather secondary data, while published and unpublished sources were used to support the primary data collected.

The frequency distribution and fundamental descriptive statistics, such as mean and standard deviation, were computed for each variable. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 25(SPSS) was used to analyze the data. Descriptive techniques such as mean and standard deviation and inferential techniques such as the T-test and multiple regression were used to analyze the data. Qualitative data from interviews and focus groups were used to support the quantitative findings. Overall, the methodology used in this study was appropriate for the research question and allowed for the collection of suitable and relevant data.

3. Results and Discussions

Perceptions of communities on the impacts of ecotourism

The study aimed to investigate the perceptions of park communities towards ecotourism development in SMNP in terms of economic, environmental, and sociocultural impacts. The study used a likert scale with 17 items to measure respondents' perceptions of ecotourism's impacts on employment opportunities, improvement of living standards, local business development, community facilities, social relationships, cultural identity and pride, and environmental issues. The scale required respondents to rate their agreement on statements ranging from 1 to 5, with a high score indicating greater levels of positive impact from ecotourism.

As shown in

Table 1, the findings showed that respondents generally had a positive perception of both the economic and socio-cultural impact of ecotourism. The mean score for the perception of economic impacts was 4.0, and the standard deviation was 0.78, while the mean score for the perception of socio-cultural impacts was 4.1, with a standard deviation of 0.55. The small difference in mean scores between groups indicated that people generally had similar views on the effects implied by the statements. The strongest agreement was found for the statements that ‘ecotourism creates employment opportunities’ and ‘encourages investments and the improvement of infrastructure,’ with means of 4.28 and 4.21, respectively. The mean measures of community perceptions on the statements ‘Ecotourism provides cultural exchange and education opportunities to the host community,’ “Ecotourism facilitates the development of community facilities and services,” and “Ecotourism creates new learning opportunities for residents” received the highest scores from the five items in the socio-cultural aspects. While the remaining two items were rated relatively low, a significant number of respondents did not perceive ecotourism's socio-cultural impacts positively.

The study also used a one-sample t-test on both the socio-cultural and economic impacts of ecotourism scores to determine if the mean score of the perception of impacts of ecotourism was significantly different from a hypothesized test value of 3, a neutral response. The sample mean of 4.0 and standard deviation of 0.78 were significantly different from 3.0, t (396) = 120, p = 0.00 for economic impacts. In the same vein, the sample mean of 4.1 and standard deviation of 0.55 were significantly different from 3 t (397) = 56.6, p = 0.05 for socio-cultural impacts, indicating that locals did not believe ecotourism had a significant negative impact on the sociocultural aspects of the study area.

Overall, the findings suggest that ecotourism development had positive impacts on the local community in terms of economic and sociocultural aspects. These results are consistent with the information gathered by FGD and key informants, which showed that ecotourism raises living standards, expands recreational and entertainment options, encourages cultural change, and strengthens the host community's sense of cultural identity.

Demographic differences in perceptions of Economic impacts of ecotourism

The study also looked at the socio-demographic variations in how various categories of local communities perceived the economic impacts. The perception of economic impacts of ecotourism by demographic factors were measured using an independent sample t-test and one-way ANOVA statistics. In post hoc analyses, the precise between-category means that were significantly different were determined using the Scheffe multiple comparison test when the F-test revealed significant mean differences on a particular variable. The table below displays a summary of the findings:

Table 2 revealed notable differences in the economic perception of ecotourism among respondents based on their gender, education level, location, and residence. Gender was found to significantly impact the economic impacts of ecotourism (t (397) = 4.46, P = 0.00), with male respondents reporting more positive perceptions (M = 27.98, SD = 3.99) than their female counterparts (M = 23.52, SD = 1.67). This disparity could be attributed to the fact that many ecotourism activities in the study area were primarily performed by men due to their physically demanding nature, resulting in low female participation rates. The interview and focus group discussion (FGD) results further supported this argument.

To participate in tourism-related activities, individuals must possess physical strength and stamina since these activities often involve lengthy walks lasting up to 12 days. If community members are unable to provide tour services, they may choose to collaborate with each other, taking turns working and splitting the meager earnings. Generally, younger individuals, primarily males, tend to participate in these activities. Those who own mules or horses can rent them out for 120 Birr per day per horse, while others can serve as mule porters for the same amount.Top of Form

The ANOVA analysis showed significant differences in how people perceived the economic effects of ecotourism in different locations F (2,394) = 7.7, P=0.001). Post-hoc comparisons revealed that households in Debark rated the positive impact of ecotourism more highly (M=29.05, SD=3.42, P=0.01) than those in Beyeda district (M=27.05, SD=5.22, P=0.01) and Janamora district (M=27.50, SD=2.86, P=0.01). The respondents' level of education was also a significant factor, with those in the formal education sector or with diploma-level education and above perceiving the economic impacts of ecotourism more positively than those with lower levels of education. This trend suggests that higher education levels may enable people to benefit more from ecotourism, as they are more likely to work as tour guides or interpreters. According to interviews, having higher levels of education also provides more opportunities to engage in lucrative ecotourism activities, improving individual livelihood survival skills. Additionally, younger respondents had a more favorable perception of the benefits of ecotourism than older respondents (M=29.11, SD=4.28).

The study's findings were reinforced by the insights gathered from focus group discussions and interviews, which highlighted the various ways that ecotourism can boost economic development by fostering the growth of hotels, lodges, resorts, restaurants, infrastructure, gift shops, travel and tour companies, and grocery stores. These facilities support a range of ecotourism-related activities and provide employment opportunities for large numbers of people, while also serving as a platform for the production and distribution of regional goods such as food, livestock, and handcrafted tourist items. The discussants agreed that ecotourism has played a significant role in driving economic growth in the study area by expanding business opportunities and creating jobs. According to the results of the SMNP management plan survey (2021), ecotourism activities in the park have created employment opportunities for over 8,000 people, or more than 2,196 households. However, the discussants also noted that the benefits of ecotourism were not evenly distributed, with some individuals reaping more benefits than others. The unequal distribution of benefits was also identified as a challenge by the study's respondents. While ecotourism has the potential to generate economic growth and development, it can also exacerbate existing social and economic disparities. For instance, some individuals may lack the resources or skills necessary to participate in ecotourism activities, limiting their ability to benefit from these opportunities. Moreover, some groups may face discrimination or exclusion from the tourism industry, further perpetuating inequalities.

Demographic differences in perceptions of the Socio-cultural impacts of ecotourism

In this study, comparisons using t-test and one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted to make sure the existence of demographic differences in the perception of socio-cultural impacts of ecotourism.

Table 4 below summarizes the results.

Based on the results presented in

Table 4, the one-way ANOVA findings indicated that the mean socio-cultural effects of ecotourism were significantly different based on respondents' education level, age, and place of residence. Specifically, there was a significant difference in perceptions of socio-cultural impacts of ecotourism among respondents with varying education levels (F (4, 396) = 4.88, p =.01). Post-hoc analyses revealed that individuals with higher education levels had more favorable perceptions of the socio-cultural effects of ecotourism than those with lower education levels. Moreover, the positive perception of the socio-cultural impacts of ecotourism decreased as education level decreased.

The ANOVA results also showed a significant difference in how people perceived the socio-cultural impacts of ecotourism based on age (F (4, 396) = 5.44, p = 0.00) and place of residence (F (4, 396) = 1.65, p = 0.01). Older age groups of respondents held more favorable opinions of the socio-cultural impacts of ecotourism compared to younger age groups, which was contradictory to the findings on the economic impact of ecotourism. On the other hand, there was no significant difference in perception of sociocultural impacts of ecotourism based on occupation, family size, or residence year.

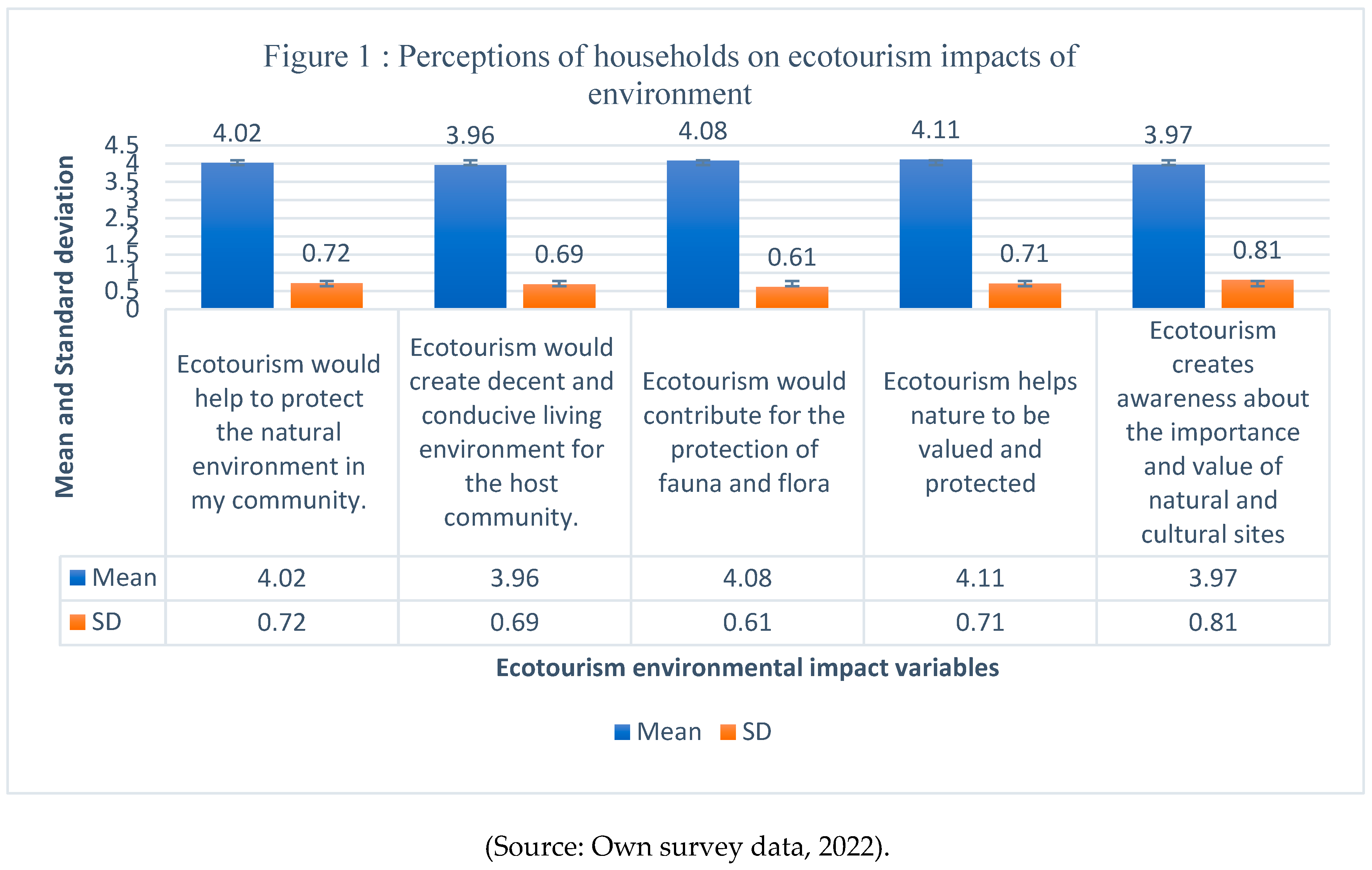

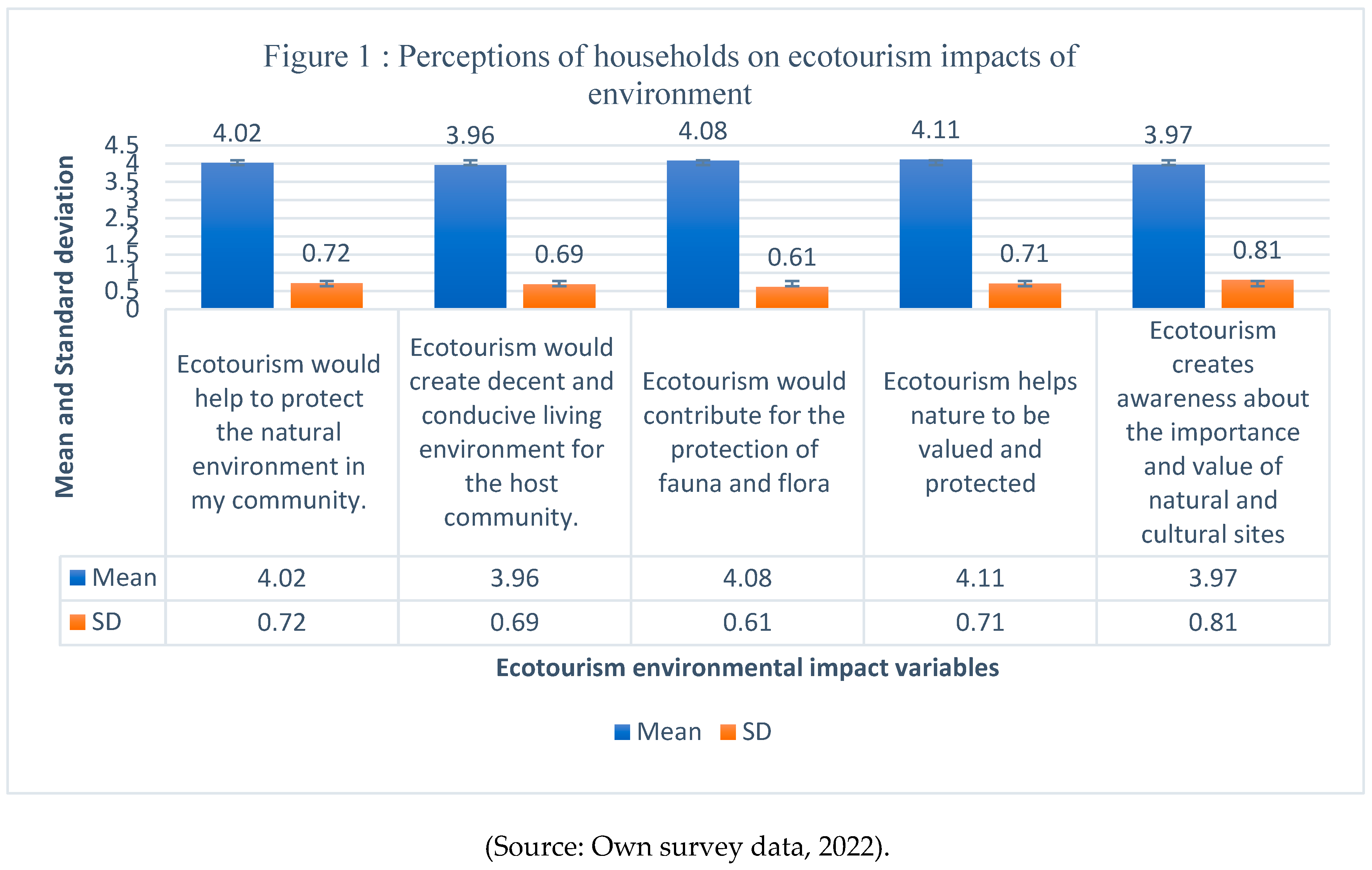

Perception of park communities on the environmental impact of ecotourism

Figure 1 displays that the respondents' average score for the environmental impacts of ecotourism was 4.02, and the standard deviation was 0.70. This indicates that the respondents had a favorable perception of ecotourism's effects, and they did not believe that ecotourism had any significant negative impact on the park environment or the local environment. The respondents valued and protected nature, and they thought that ecotourism helped to preserve and protect the environment in their communities. The mean and standard scores of the environmental impacts of ecotourism that were favored by the local communities are as follows: "Ecotourism would help to protect the natural environment in my community." (M = 4.02, SD = 0.72)", "Ecotourism helps nature to be valued and protected (M = 4.11, SD = 0.71), "Ecotourism creates awareness about the importance and value of natural and cultural sites (M = 3.97, SD = 0.81), "Ecotourism would create a decent and conducive living environment for the host community (M = 3.96, SD = 0.69)," and "Ecotourism will improve the local community's awareness of the protection of fauna and flora in my community (M = 4.08, SD = )". The communities in Semien Mountain National Park believe that ecotourism has benefited them based on these five factors under the category of environmental impact. Additionally, in an interview with park officers, it was acknowledged that the communities largely agreed that the park's development as an ecotourism destination sparked local efforts to protect the environment. The development of ecotourism could potentially address the issues related to the conservation and development impacts on biodiversity, endangered species, people, and the environment.

In contrast to the expected benefits, the outcomes of the interviews and focus groups indicated that ecotourism has a detrimental effect on the wildlife and environment of the park. Human intervention within the park due to ecotourism activities has significantly increased, leading to congestion of tourists in certain areas, which has had a significant negative impact. The interviews and focus groups revealed several negative impacts of tourism on the park, including litter problems, unhygienic campsites, animal disturbance, and the utilization of wood for campfires and cooking. Additionally, the park's resources were negatively affected by the establishment of infrastructure such as road construction and the introduction of horses and mules from faraway places. To test the environmental impact of ecotourism, a one-sample t-test was conducted, revealing a mean of 20.16 (SD = 2.95), which was significantly different from the neutral result of 30 (t (396) = 34.8, p = 0.00). The ANOVA and T-test findings revealed no significant variations in the environmental impact of ecotourism based on respondents' age, gender, or place of residence, except for their level of education.

Park communities’ level of participation in ecotourism

The literature seems to recognize the value of local community involvement in the expansion of the tourism sector. Tosun (2000) added that "the opportunities for local communities to participate may change over time with the type and scale of tourism produced, entrance requirements, and the market served." Therefore, using a household survey questionnaire, respondents were asked to check the likelihood of participation ecotourism in the study area. Researchers were able to assess how much the communities were involved in ecotourism with the change of different demographic independent variables. A logistic regression analysis is presented in

Table 5 to illustrate the relationship between demographic traits (independent variables) and participation in ecotourism activities (dependent variables).

According to

Table 5, a total of 252 households (equivalent to 63.5% of the entire sample) participated in ecotourism activities. The logistic regression model revealed that when all independent variables were considered together, they accounted for 21.2% of the variance in the dependent variable. The logistic regression analysis further revealed that gender, education level, and household location were the three demographic variables that were significantly related to participation in ecotourism activities. Therefore, these variables were directly and significantly associated with the probability of households participating in ecotourism activities. The findings also revealed that men were more likely than women to participate in ecotourism, with a 1.85-unit increase in male participation resulting in a change in ecotourism participation. This can be attributed to the fact that ecotourism activities were generally considered to be more suitable for men than women due to the physical and courageous demands of activities such as hiking, camping, and trekking. The results of the logistic regression model showed that age, marital status, family size, and landholding size had no significant effect on participation in ecotourism activities. However, the study revealed that participation in ecotourism activities increased by 0.238 for every one-unit increase in education level. The interview results also revealed that individuals with higher levels of education were more likely to work in ecotourism-related professions, such as tour guiding and travel agency services. Finally, the results showed that the location of household respondents had a statistically significant impact on participation in ecotourism activities. Specifically, for every one-unit increase in the number of individuals in Debark, participation in ecotourism activities increased by 0.42.

Discussions

According to the study's findings, the SMNP park-adjacent communities generally had a favorable perception of the socioeconomic and environmental impacts of ecotourism. Additionally, it demonstrated that there was little variation in the mean scores, which suggests that people had similar views on the effects implied by the statements. Despite their belief that park communities participated to a lesser extent, they claimed that the community outside the park controlled the majority of the economic benefits or revenues derived from ecotourism services. The study's findings also showed that the residents of the park's households were aware of the growth of ecotourism and understood its widespread effects—both good and bad—on the area's environment, economy, and sociocultural aspects.

Similar to this outcome, ecotourism is constantly criticized in many regions of Ethiopia for its underdevelopment, the disempowerment of the local populations, and even the unfair profit of the host community of local destination locations, primarily in rural areas. A large proportion of the income from ecotourism taking place in protected areas never reaches the majority of the host people. It mainly benefits the tourist service providers who came out of the destinations (Eshetie, 2012; Weinberg, 2010; and UNDP, 2012). This result was also supported by findings from previous studies out of Ethiopia, like Goodwin (2002) and Kiss (2004), which showed that although ecotourism in the park brought additional income and employment opportunities, the rural communities near the park (for example, the Komodo National Park in Indonesia) remain largely marginalized and unprivileged from the ecotourism-related developments, while the majority of the ecotourism benefits go to the nearby town residents. Similar results were also obtained in the study conducted in South African protected areas, where the local communities had a negative attitude towards the park since they were not involved in many ecotourism activities.

In contrast to the above findings, the practical experiences of many countries like Nepal, many Asian countries, Kenya, and Tanzania revealed the benefit of ecotourism activities to the host communities. Nepal's community-based ecotourism management is a unique example of community engagement for conserving the environment and promoting sustainable livelihoods, with effective management, empowerment of local communities, and synergetic efforts of customary governance, non-governmental organizations, and government agencies (Yaw et al., 2019; Manu et al., 2012; and Muganda, 2009). Ecotourism has also been used as an alternative livelihood strategy in Tanzania and Ghana, providing income and employment opportunities, as well as conservation of the local ecosystem and culture (Yaw et al., 2019; Manu, et al., 2012; Muganda, 2009).

Conclusions

The study's findings demonstrate that the local communities in the study area has a positive perception on socio-cultural, economic and environment impacts of ecotourism. This implies that the host community's perception of the benefits of ecotourism is correlated with how inclined to support the growth of ecotourism and attribute the improvement of their community to tourism development. A closer look at the underlying statistics of the mean scores, however, reveals that the perceived impact of ecotourism is only moderately positive, indicating that the advantages of tourism are not yet fully appreciated. Out of the three types of tourism impacts, the economic benefit of ecotourism to local communities has received the most attention in the study. Respondents had a more positive perception of ecotourism's economic benefits than of its socio-cultural and environmental effects.

Additionally, the results of this study showed that locals' perceptions of the economic, sociocultural, and environmental effects of tourism varied significantly according to their socio-demographic characteristics. More specifically, it was really fascinating to observe how demographic factors influenced how tourism impacted the economy. The benefits of ecotourism were felt more strongly by men than by women and by respondents with higher levels of education (diploma holders than illiterates). In addition, the tourist destinations in the Debark woreda (district) have a more favorable perception of the economic advantages of ecotourism than their rivals (Janamora and Beyeda study areas). Overall, the results show that citizens' perceptions of tourism's economic effects are more variable than those of its impacts on the environment and socio-cultural in general. Additionally, the findings demonstrated that, of all the socio-demographic factors investigated, gender and educational attainment offered statistically significant variations on the three dimensions of the ecotourism effect taken into consideration in the current study.

Recommendation

It is known that ecotourism has been used as one viable strategy to narrow and resolve the conflicting objectives of conservation and development in the park. With reference to this model, the study's findings have important policy implications for the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Agency, the Ministry of Tourism, and other stakeholders. Hence, the researchers have the following recommendations

To maximize benefits and reduce negative effects, important stakeholders, including the Park office, the EWCA, governmental organizations, the private sector, and the local community, should work together closely and should step up their current initiatives to fully realize the greatest benefits for residents and to develop ecotourism development at the destination. Participation from multi-sectoral stakeholders is necessary to maximize the advantages for nearby communities. There should be a formal relationship between the various tourism stakeholders that is structured, has boundaries, and is clearly defined.

Both the local and federal governments, concerned sectors (EWCA), tourism offices at all levels, and other concerned bodies must improve the variety of recreational activities if they want to encourage tourists to remain longer and bring about the development of the tourism industry. As a result, the study site must establish, build, and improve road construction, camping sites, lodges, even arrangements, gardens, and other infrastructure. Communities are urged to make investments in the industry because tourists don't only come to one location.

Public education on the importance of ecotourism: the local communities especially those who reside nearby the tourist attraction sites shall be well informed about the importance of tourism development and make them to pledge to cooperate for the sustainable tourism development in the area. Education of locals about the potential benefits of tourism is essential to securing support for tourism development and establishing sustained community development.

Data availability

The study is a part of PhD dissertation. Hence, the data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declaration of conflict of interest

The author(s) declare(s) that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of the study particularly for the household heads and the park staff members in the study areas for their sound input for this study.

References

- Aarti, M. , & Sunita, B. (2013). Innovative trends in tourism management-need of the hour. Golden Research Thoughts, 2(9).

- Boo, E. (1990). Ecotourism: the potentials and pitfalls: country case studies. WWF.

- Cater, E. (1994). Ecotourism in the Third World: problems and prospects for sustainability. Ecotourism: a sustainable option. 69-86.

- Ethiopian Economics Association. (2011). the development of key national policies with respect to rainwater management in Ethiopia: A review. NBDC Technical Report.

- Harilal, V. , & Tichaawa, T. M. (2018). COMMUNITY AWARENESS AND UNDERSTANDING OF ECO-TOURISM WITHIN THE CAMEROONIAN CONTEXT. South African Geographers, 1, 163.

- Harun, R.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Sirwan, K.; Arion, F.H.; Muresan, I.C. Attitudes and Perceptions of the Local Community towards Sustainable Tourism Development in Kurdistan Regional Government, Iraq. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimengsi, J.N. Threats to Ecotourism Development and Forest Conservation in the Lake Barombi Mbo Area (LBMA) of Cameroon. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 2014, 17, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, D.-W.; Stewart, W.P. A structural equation model of residents’ attitudes for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2002, 23, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Wall, G. Ecotourism: towards congruence between theory and practice. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H. S. , & Stubbles, R. L. (1998). Residents' attitudes and importance-performance evaluation toward the impacts of tourism in the Black Hills, USA. Journal of Korean Society of Forest Science, 87(2), 179-187.

- Stronza, A. (2002). Revealing the true promise of community-based ecotourism: The case of Posada Amazonas. In Sustainable Development and management of ecotourism in the Americas preparatory conference for the International Year of Ecotourism.

- Wang, Y. (.; Pfister, R.E. Residents' Attitudes Toward Tourism and Perceived Personal Benefits in a Rural Community. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurahman, A.Z.A.; Ali, J.K.; Khedif, L.Y.B.; Bohari, Z.; Ahmad, J.A.; Kibat, S.A. Ecotourism Product Attributes and Tourist Attractions: UiTM Undergraduate Studies. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 224, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhay, T. , Abiew, D., & Leulseged, T. (2019). Challenges and opportunities of the tourism industry in Amhara Regional State: The World Heritage sites in focus. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 8(5).

- Abukari, H.; Mwalyosi, R.B. Local communities’ perceptions about the impact of protected areas on livelihoods and community development. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amogne, A.E. Development of community based ecotourism in Borena-Saynt National Park, North central Ethiopia: Opportunities and Challenges. J. Hosp. Manag. Tour. 2014, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bown, N. K. (2010). Contested models of marine protected area (MPA) governance: A Case Study of the Cayos Cochinos, Honduras SUBMITTED TO FULFIL THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SCHOOL OF GEOGRAPHY, POLITICS AND SOCIOLOGY.

- Chamboko-Mpotaringa, M.; Tichaawa, T. Tourism Digital Marketing Tools and Views on Future Trends: A Systematic Review of Literature. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadinga, W.F.; Tchamba, N.M.; Barnabas, N.N.; Nyong, P.A.; Chimi, C.D.; Diabe, E.S.; Reeves, M.F. Assessing the impact of ecotourism on livelihood of the local population living around the Campo Maan National Park, South Region of Cameroon. J. Hosp. Manag. Tour. 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, R.; Chiciudean, G.O.; Sirwan, K.; Arion, F.H.; Muresan, I.C. Attitudes and Perceptions of the Local Community towards Sustainable Tourism Development in Kurdistan Regional Government, Iraq. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Yang, L.; Min, Q. Community Participation in Nature Conservation: The Chinese Experience and Its Implication to National Park Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holladay, P.J.; Ormsby, A.A. A comparative study of local perceptions of ecotourism and conservation at Five Blues Lake National Park, Belize. J. Ecotourism 2011, 10, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K, S. O. , I, A. E. ( 2014(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Kimengsi, J.N. Threats to Ecotourism Development and Forest Conservation in the Lake Barombi Mbo Area (LBMA) of Cameroon. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 2014, 17, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Vogt, C.A.; Luo, J.; He, G.; Frank, K.A.; Liu, J. Drivers and Socioeconomic Impacts of Tourism Participation in Protected Areas. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e35420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariam, T.K. Ethiopia: Opportunities and Challenges of Tourism Development in the Addis Ababa-upper Rift Valley Corridor. J. Tour. Hosp. 2015, 04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaiwa, J.E.; Stronza, A.L. The effects of tourism development on rural livelihoods in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, E. , Hassan, K. ( 36(1), 85–92. [CrossRef]

- Pengwei, W.; Linsheng, Z. Tourist Willingness to Pay for Protected Area Ecotourism Resources and Influencing Factors at the Hulun Lake Protected Area. J. Resour. Ecol. 2018, 9, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reindrawati, D. Y. , Rhama, B., & Hisan, U. F. C. (2022). Threats to Sustainable Tourism in National Parks: Case Studies from Indonesia and South Africa. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 11(3), 919–937. [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; Jaafar, M.; Mohamad, D. Strengthening Sustainability: A Thematic Synthesis of Globally Published Ecotourism Frameworks. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshome, E.; Shita, F.; Abebe, F. Current community based ecotourism practices in Menz Guassa community conservation area, Ethiopia. GeoJournal 2020, 86, 2135–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-C.; Hung, W.-T.; Shang, J.-K. Measuring the Cost Efficiency of International Tourist Hotels in Taiwan. Tour. Econ. 2006, 12, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xu, W.; Jiang, C.; Dai, H.; Sun, Q.; Cheng, K.; Lee, C.-H.; Zong, C.; Ma, J. Evaluating Communities’ Willingness to Participate in Ecosystem Conservation in Southeast Tibetan Nature Reserves, China. Land 2022, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Results of descriptive statistics for perceived impacts of ecotourism (N= 397).

Table 1.

Results of descriptive statistics for perceived impacts of ecotourism (N= 397).

| No |

Economic Impacts |

M |

SD |

| 1 |

Ecotourism brings economic benefits for the residents |

3.95 |

0.75 |

| 2 |

Ecotourism contributes to improve incomes and living standards |

4.00 |

0.72 |

| 3 |

Ecotourism creates a local business environment |

4.05 |

0.72 |

| 4 |

Ecotourism creates employment opportunities for local residents |

4.28 |

0.69 |

| 5 |

Ecotourism encourages investments and infrastructure improvement |

4.21 |

0.75 |

| 6 |

Ecotourism promotes local products by creating new market |

3.86 |

0.89 |

| 7 |

Ecotourism generates substantial tax revenues for government |

3.65 |

1.0 |

| |

Average score Economic impacts |

4.0 |

0.78 |

| |

Socio-cultural impacts |

Mean |

SD |

| 1 |

Ecotourism provides cultural exchange and education opportunities to the host community. |

4.33 |

0.51 |

| 2 |

Ecotourism facilitates the development of community facilities and services |

4.14 |

0.54 |

| 3 |

Ecotourism preserves cultural values and customs of the community |

3.91 |

0.59 |

| 4 |

Ecotourism creates new learning opportunities for residents |

4.05 |

0.57 |

| 5 |

Ecotourism increases pride in cultural identity |

4.04 |

0.55 |

| |

Average score Socio-Cultural impacts |

4.10 |

0.55 |

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Summary of t-Tests and ANOVA Results for Scores on the Economic effects of Ecotourism (N = 397).

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Summary of t-Tests and ANOVA Results for Scores on the Economic effects of Ecotourism (N = 397).

| |

Mean |

SD |

F Ratio |

F Prob. |

| Gender |

|

|

4.6 |

0.00 |

| Male |

27.98 |

3.93 |

|

|

| Female |

23.52 |

1.67 |

|

|

| Woreda(district) of residence |

|

|

7.71 |

0.001 |

| Debark |

29.05 |

3.42 |

|

|

| Janamora |

27.50 |

2.86 |

|

|

| Beyeda |

27.05 |

5.22 |

|

|

| Highest education level |

|

|

5.33 |

0.001 |

| Illiterate |

29.00 |

2.74 |

|

|

| Read and Write |

29.33 |

3.77 |

|

|

| Primary |

30.12 |

.29 |

|

|

| Secondary |

31.50 |

6.88 |

|

|

| Diploma and above |

31.40 |

5.12 |

|

|

| Age |

|

|

1.34 |

.039 |

| 18-29 years |

29.11 |

4.28 |

|

|

| 30-45 years |

28.12 |

4.25 |

|

|

| 46-60 years |

27.73 |

4.06 |

|

|

| Above 60 years |

27.12 |

2.47 |

|

|

Table 4.

Summary of T-test and ANOVA results for scores on the socio cultural impacts of ecotourism.

Table 4.

Summary of T-test and ANOVA results for scores on the socio cultural impacts of ecotourism.

| Variables |

|

Mean |

SD |

F Ratio |

F Prob. |

| Sex |

M |

20.61 |

1.85 |

5.23

5.44 |

0.01

0.00 |

| F |

18.43 |

1.99 |

| Age |

18-29 |

20.34 |

2.01 |

| 30-45 |

20.43 |

2.13 |

| 46-60 |

20.8 |

1.65 |

| Above to 60 |

20.5 |

1.20 |

| Education |

Illiterate |

20.09 |

1.89 |

4.88 |

0.01 |

| Basic education |

20.63 |

2.0 |

| Primary education completed |

20.84 |

1.62 |

| Secondary education complete |

20.9 |

1.48 |

| Diploma and above |

21.85 |

2.34 |

Table 5.

Logistic regression showing on the relationship between independent variables and ecotourism activity participation in SMNP.

Table 5.

Logistic regression showing on the relationship between independent variables and ecotourism activity participation in SMNP.

| Independent Variables |

B |

P-level |

Exp(B) |

| Gender |

1.85* |

0.023 |

2.021 |

| Age |

-0.43 |

0.412 |

0.233 |

| Education |

0.238* |

0.032 |

3.121 |

| Place of residence |

0.42* |

0.041 |

3.661 |

| Marital status |

0.079 |

0.321 |

0.123 |

| Landholding size |

0.432 |

0.161 |

1.121 |

| Family size |

0.313 |

0.845 |

0.321 |

| Number of observation |

397 |

|

|

| -2lig likelihood |

112.232 |

|

|

| NagelkerkerR2

|

0.212 |

|

|

| Level of significance |

5% |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).