Submitted:

21 April 2023

Posted:

23 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Search methods.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

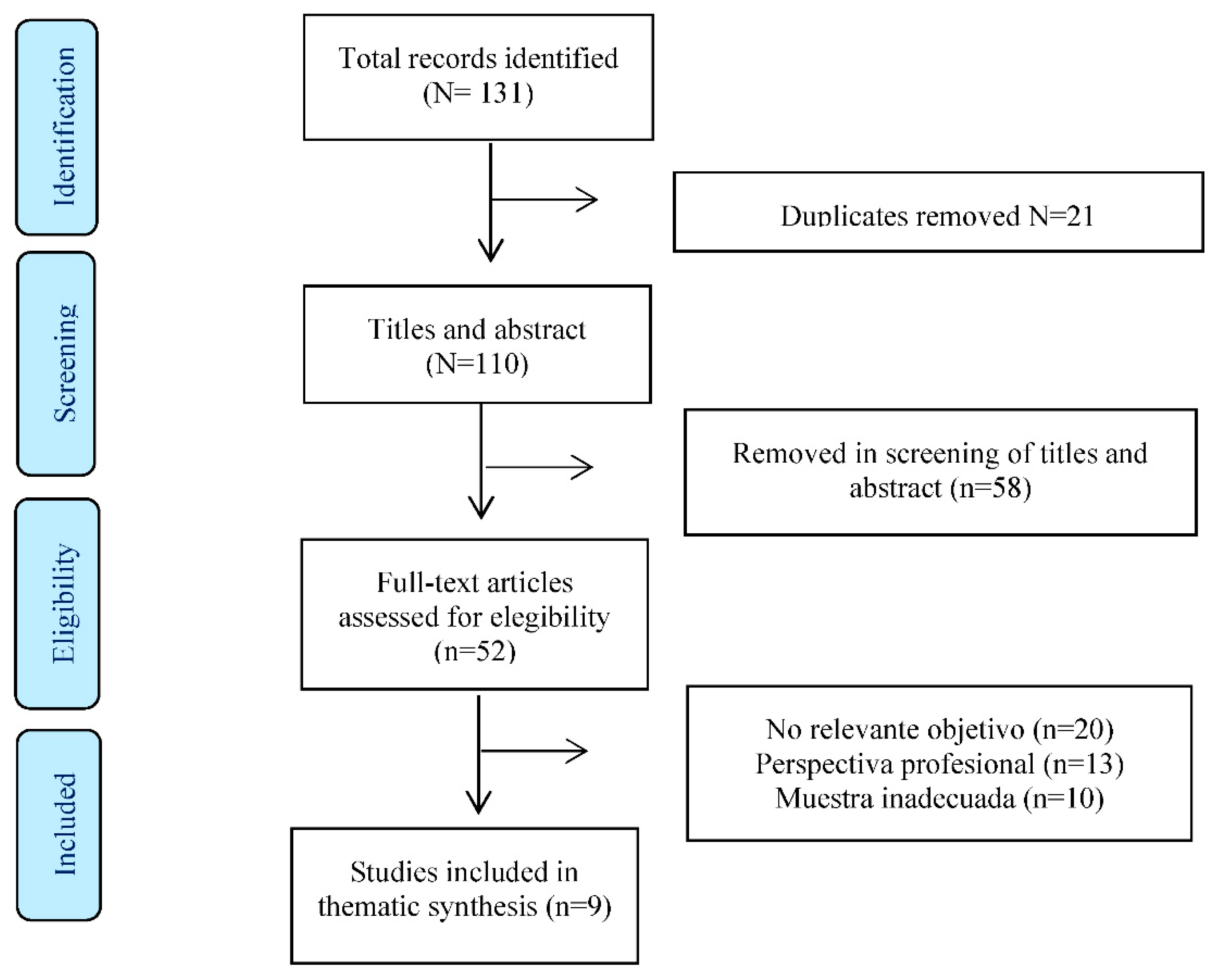

2.4. Results of the search.

2.5. Quality assessment.

| Keygnaert et al., 2014 |

2.6. Data extraction

Data synthesis and analysis

| STAGE 2 |

2.7. Rigor

3. Results

3.1. The need to focus emergency care on SRH.

3.1.1. IMW: victims of trafficking and sexual exploitation.

“They come and rape you for days and when it suits them, they leave you there, bleeding... and you have to get on with the journey as best you can" [10]

3.1.2. The need to develop suitable safety protocols.

“Who is protecting my baby? Who is protecting my family?” [10]

3.2. Unsatisfactory clinical experiences.

3.2.1. The need for interpreters.

"I rang the bell several times asking for help, I was worried that something was wrong with the baby who was screaming and screaming. After a long time, the staff came in and said something incomprehensible in Swedish, then they left and did not come back.” [24]

“She (the physician) didn't explain what the test would be like properly; I thought it was the one with the needle, so I said no.” [18]

3.2.2. Healthcare providers’ lack of cultural competence.

"They claimed it was not amniotic fluid, but rather I had urinated on myself. I said I had already given birth to four children. I know the difference between urine and amniotic fluid. They never looked at the amniotic fluid and never performed a cardiotocography. The fluid and blood continued to leak out over the next week.” [18]

3.3. Forced reproduction.

3.3.1. Practices that put the IMW’s personal health at risk.

“HIV and cancer are diseases… in my eyes, HIV is the worst” [25]

"For example, I used the calendar method as contraception. For a year and a half, I only used the calendar method for contraception " [1]

3.3.2. Pregnancies characterised by IMW’s irregular status.

"With my two children I always started going to the gynaecologist after 6 months of pregnancy. With the other one I went at eight months and I had no problems with my son. I said to myself ‘I can have my daughter without anyone needing to care for me'." [17]

“The doctor might check the baby and put the instruments inside the baby, which could accidentally damage it and cause a miscarriage.” [18]

"I got pregnant and was working at the time. I said: ... 'The lady will fire me because she doesn't want me to work.’ So I didn't say anything to the lady.” [18]

3.3.3. Unsafe sex life.

“I asked my partner to use condoms, but he said that masculinity should be felt and left free, not tied to a condom. And he told me that he would leave with his other girlfriends and I should find another partner.” [11]

“No, I don't use protection with my boyfriend' (sex worker). If it itches you can use antibiotics or preventative gels..." [24]

3.4. Alternating between formal and informal healthcare services.

3.4.1. Access to information and care.

“They said they couldn't do anything because I don’t have papers,'you're undocumented', after sitting there for 10 hours.... We felt ignored and drove home.” [24]

"No one listened to my wishes. I was forced to have a vaginal delivery, regardless of my pre-existing risks." [26]

"It was really challenging, I was in labour for two days. The doctors came, the interns came, the nurses came, they kept coming, but they didn't treat me." [26].

3.4.2. Unsafe abortions.

“If I ever notice I miss my period in the first month, I will start clenching and banging my stomach very hard. I will work hard physically, I will jump and massage myself. I will drink a lot of herbal water. If I start early, I will be able to get the baby out easily.” [26]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keygnaert, I.; Vettenburg, N.; Roelens, K.; Temmerman, M. Sexual health is dead in my body: Participatory assessment of sexual health determinants by refugees, asylum seekers and undocumented migrants in Belgium and the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Organization of Migration. World Migration Report 2020. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- International Organization of Migration. World Migration Report 2022. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/WMR-2022.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) [National Institue of Statistics]. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/t20/e245/p08/l0/&file=02005.px (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Consejo Económico y Social (CES) [Economic and Social Council] (2019). La inmigración en España: Efectos y oportunidades. [Immigration in Spain: Effects and opportunities] Available online:. Available online: https://www.ces.es/documents/10180/5209150/Inf0219.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- International Organization for Migration. Glossary on Migration. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf (accessed on 27th March 2023).

- Granero-Molina, J.; Jiménez-Lasserrrotte, M. D. M.; Fernández-Sola, C.; Hernández-Padilla, J. M.; Sánchez Hernández, F.; López Domene, E. Cultural Issues in the Provision of Emergency Care to Irregular Migrants Who Arrive in Spain by Small Boats. J Transcult Nurs. 2019, 30, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Real Decreto-ley 16/2012, de 20 de abril, de medidas urgentes para garantizar la sostenibilidad del Sistema Nacional de Salud y mejorar la calidad y seguridad de sus prestaciones. [Royal Decree-Law 16/2012, of 20th April, on urgent measures to guarantee the sustainability of the National Health System and improve the quality and safety of its services.] Available online:. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2012/BOE-A-2012-5403-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Real Decreto-ley 7/2018, de 27 de julio, sobre el acceso universal al Sistema Nacional de Salud. [Royal Decree-Law 7/2018, of 27th July, on universal access to the National Health System.] Available online:. Available online: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2018/07/30/pdfs/BOE-A-2018-10752.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- López-Domene, E.; Granero-Molina, J.; Fernández-Sola, C.; Hernández-Padilla, J. M.; López-Rodríguez, M.M.; Fernández-Medina, I. M. , Guerra-Martín, M. D., Jiménez-Lasserrrotte, M. M. Emergency care for women irregular migrants who arrive in spain by small boat: A qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019, 16(18). [CrossRef]

- Hegde, S.; Hoban, E.; Nevill, A. Unsafe abortion as a birth control method: Maternal mortality risks among unmarried Cambodian migrant women on the Thai-Cambodia border. Asia Pac J Public Health, 2012, 24, 989–1001. [CrossRef]

- Chiarenza, A.; Dauvrin, M.; Chiesa, V.; Baatout, S.; Verrept, H. Supporting access to healthcare for refugees and migrants in European countries under particular migratory pressure. BMC Health Serv Res, 2019, 19, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, C. (2018). “For a better life …“A study on migration and health in Nicaragua.’ Glob Health Action, 2018, 11, 1428467. [CrossRef]

- Granero-Molina, J.; Jiménez-Lasserrotte, M.D.M.; Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Fernández-Medina, I.M.; López-Rodríguez, M.M. , Fernández-Sola, C. Physicians' experiences of providing emergency care to undocumented migrants arriving in Spain by small boats. Int Emerg Nurs, 2021, 56, 101006. [CrossRef]

- Granero-Molina, J.; Jiménez-Lasserrotte, M.D.M.; Fernández-Medina, I.M.; Ruiz-Fernández, M.D.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Fernández-Sola, C. Nurses' experiences of emergency care for undocumented migrants who travel by boats. Int Nurs Rev. 2022, 69, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Lasserrotte, M.D.M.; López-Domene, E. ; Fernández-Sol,a C.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Fernández-Medina, I.M.; Granero-Molina J. Accompanied child irregular migrants who arrive to Spain in small boats: Experiences and health needs. Glob Public Health, 2020a, 15, 345-357. [CrossRef]

- Barona-Vilar, C.; Más-Pons, R.; Fullana-Montoro, A.; Giner-Monfort, J.; Grau-Muñoz, A.; Bisbal-Sanz, J. Perceptions and experiences of parenthood and maternal health care among Latin American women living in Spain: A qualitative study. Midwifery, 2013, 29, 332–337. [CrossRef]

- Sami, J.; Lötscher, K. C. Q.; Eperon, I.; Gonik, L.; De Tejada, B. M.; Epiney, M.; Schmidt, N. C. Giving birth in Switzerland: A qualitative study exploring migrant women’s experiences during pregnancy and childbirth in Geneva and Zurich usingfocus groups. Reprod Health, 2019, 16, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Florczak, K. L. In the Zeal to Synthesize: A Call for Congruency. Nurs Sci Q, 2013, 26, 220–225. [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care, 2007, 19, 349–357. [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res, 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (2020). Checklist for qualitative research. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 28 March 2023).

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2008, 8, 45. [CrossRef]

- Barkensjö, M.; Greenbrook, J. T. V; Rosenlundh, J.; Ascher, H.; Elden, H. The need for trust and safety inducing encounters: a qualitative exploration of women's experiences of seeking perinatal care when living as undocumented migrants in Sweden. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 2018, 18, 217. [CrossRef]

- Coma, N.; Mejía-Lancheros, C.; Berenguera, A. Pujol-Ribera, E. Risk perception of sexually transmitted infections and HIV in Nigerian commercial sex workers in Barcelona: a qualitative study. BMJ Open, 2015, 5:e006928. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, B. Health inequities faced by Ethiopian migrant domestic workers in Lebanon. Health Place, 2018, 50, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Lasserrotte, M. D. M. , López-Domene, E., Hernández-Padilla, J. M., Fernández-Sola, C., Fernández-Medina, I. M., Faqyr, K. E. M. E., Dobarrio-Sanz, I., & Granero-Molina, J. Understanding Violence against Women Irregular Migrants Who Arrive in Spain in Small Boats. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 2020, 8, 299. [CrossRef]

- Pottie, K.; Martin, J. P.; Cornish, S.; Biorklund, L.M.; Gayton, I.; Doerner, F. Schneider, F. Access to healthcare for the most vulnerable migrants: a humanitarian crisis. Conflict health, 2015; Volume 9, p. 16. [CrossRef]

- Matose, T.; Maviza, G.; Nunu, W. N. Pervasive irregular migration and the vulnerabilities of irregular female migrants at Plumtree border post in Zimbabwe. J Migr Health, 2022; 5, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agadjanian, V.; Oh, B.; Menjívar, C. ). (Il) legality and psychosocial well-being: Central Asian migrant women in Russia. J Eth Migr Stud, 2022, 48, 53–73. [CrossRef]

- Mamuk, R.; Şahin, N. H. Reproductive health issues of undocumented migrant women living in Istanbul. Eur J Contracep Reprod Health Care, 2021, 26, 202–208. [CrossRef]

- Bahamondes, L.; Laporte, M.; Margatho, D.; de Amorim, H. S. F.; Brasil, C.; Charles, C. M.; Becerra, A.; Hidalgo, M. M. Maternal health among Venezuelan women migrants at the border of Brazil. BMC Public Health, 2020, 20, 1771. [CrossRef]

- Marti Castaner, M.; Slagstad, C.; Damm Nielsen, S.; Skovdal, M. Tactics employed by healthcare providers in the humanitarian sector to meet the sexual and reproductive healthcare needs of undocumented migrant women in Denmark: A qualitative study. Sex Reprod Healthc, 2022. 34. [CrossRef]

- Funge, J. K.; Boye, M. C.; Parellada, C. B.; Norredam, M. Demographic characteristics, medical needs and utilisation of antenatal Care among pregnant undocumented migrants living in Denmark between 2011 and 2017. Scand J Public Health, 2022, 50, 575–583. [CrossRef]

- Deeb-Sossa, N.; Olavarrieta, C. D.; Juárez-Ramírez, C.; García, S. G.; Villalobos, A. Experiences of undocumented Mexican migrant women when accessing sexual and reproductive health services in California, USA: a case study. Cad Saude Publica, 2013, 29, 981–991. [CrossRef]

- Mengesha, Z. B.; Perz, J.; Dune, T.; Ussher, J. Refugee and migrant women's engagement with sexual and reproductive health care in Australia: A socio-ecological analysis of health care professional perspectives. PloS one, 2017, 12, e0181421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndumbi, P.; Del Romero, J.; Pulido, F.; Velasco, M.; Dronda, F.; Blanco, J. R.; García, P.; Ocaña, I.; Belda-Ibañez, J. , Del Amo, J.; … Barriers to health care services for migrants living with HIV in Spain. Eur J Public Health, 2018, 28, 451–457. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, C.; Hossain, M.; Watts, C. Human trafficking and health: a conceptual model to inform policy, intervention and research. Soc Sci Med, 2011, 73, 327–335. [CrossRef]

- Metusela, C.; Ussher, J.; Perz, J.; Hawkey, A.; Morrow, M.; Narchal, R.; Estoesta, J.; Monteiro, M. "In My Culture, We Don't Know Anything About That": Sexual and Reproductive Health of Migrant and Refugee Women. Int J Behav Med, 2017, 24, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Linares, J. M.; López-Entrambasaguas, O. M.; Fernández-Medina, I. M.; Berthe-Kone, O.; Fernández-Sola, C.; Jiménez-Lasserrotte, M.D.M.; Hernández-Padilla, J.M.; Canet-Vélez, O. Lived experiences and opinions of women of sub-Saharan origin on female genital mutilation: A phenomenological study. J Clin Nurs, 2022, 10.1111/jocn.16294. [CrossRef]

- González-Timoneda, A.; González-Timoneda, M.; Cano, A.; Ruiz, V. Female Genital Mutilation Consequences and Healthcare Received among Migrant Women: A Phenomenological Qualitative Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2021, 18(13), 7195. [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.; Tweheyo, R.; McGarry, J.; Eldridge, J.; Albert, J.; Nkoyo, V.; Higginbottom, G. Improving care for women and girls who have undergone female genital mutilation/cutting: qualitative systematic reviews. NIHR Journals Library, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Visalli, G.; Facciolà, A.; Carnuccio, S. M.; Cristiano, P.; D'Andrea, G.; Picerno, I.; Di Pietro, A. Health conditions of migrants landed in north-eastern Sicily and perception of health risks of the resident population. Public health, 2020. 185, 394–399. [CrossRef]

- Garbett, A.; de Oliveira, N. C.; Riggirozzi, P.; Neal, S. The paradox of choice in the sexual and reproductive health and rights challenges of south-south migrant girls and women in Central America and Mexico: A scoping review of the literature. J Migr Health, 2022, 7, 100143. [CrossRef]

- Auli, N. C.; Mejía-Lancheros, C.; Berenguera, A.; Pujol-Ribera, E. Risk perception of sexually transmitted infections and HIV in Nigerian commercial sex workers in Barcelona: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 2015, 5. [CrossRef]

- Mona, H.; Andersson, L. M. C.; Hjern, A.; Ascher, H. Barriers to accessing health care among undocumented migrants in Sweden - a principal component analysis. BMC Health Serv Res, 2021, 21, 830. [CrossRef]

- Serre-Delcor, N.; Oliveira, I.; Moreno, R.; Treviño, B.; Hajdók, E.; Esteban, E.; Muri-as-Closas, A.; Denial, A.; Evangelidou, S. A Cross-Sectional Survey on Profes-sionals to Assess Health Needs of Newly Arrived Migrants in Spain. Front Public Health, 2021. 9, 667251. [CrossRef]

| Article | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedge et al, 2012 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Keygnaert et al., 2014 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Auli et al., 2015 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Barona-Vilar et al., 2013 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ↔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ |

| Sami et al., 2019 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| López-Domene et al., 2019 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Barkensjö et al., 2018 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Fernández, 2018 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Deeb-Sossa et al., 2013 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ↔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Stage | Description | Steps |

|---|---|---|

| STAGE 1 | Text coding | Recall review question Read/re-read findings of the studies Line-by-line inductive coding Review of codes in relation to the text |

| STAGE 2 | Development of descriptive themes | Search for similarities/differences between codes Inductive generation of new codes Write preliminary and final report |

| STAGE 3 | Development of analytica themes | Inductive analysis of sub-themes Individual/independent analysis Pooling and group review |

| Author and year | Country | Sample (IMW) | Age (years) | Interview duration | Data collection |

Data analisys |

Main Theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hegde et al.,2012 | Cambodia | 15 | 18-28 | Not interviewed | IDI | Manual analysis of codede data | Attitudes /practice of unsafe abortions |

| Auli et al., 2015 | Spain | 8 | 23-40 | 30 min. | IDI | Content analysis | Risk of STIs and HIV in sex workers |

| Barona-Vilar et al., 2013) | Spain | 26 | 20-35 | 3 h. | FGs | Thematic analyss | IMW’s experiences of maternity care |

| Sami et al., 2019 | Switzerland | 33 | 21-40 | Not interviewed | FGs | Analysis of themes and subthemes | Experiences of maternal health services |

| López-Domene et a., 2019 | Spain | 13 | 18-35 | 18 min. | IDI | Valerie Fleming stages | IMW’s health needs |

| Barkensjö et al., 2018 | Sweden | 13 | 18-36 | 45 min | IDI | Qualitative analysis of content | Clincial experiences of birth/pregnancy |

| Fernández, 2018 | Lebanon | 35 | Not provided | 1 h. | IDI | Ethnographic analysis of themes | Unequal access to care for IMW |

| Deeb-Sossa et al., 2013 | United States | 8 | 20-45 | Not interviewed | Life story | Analysis of statements | Cultural needs and access restrictions |

| Keygnaert et al., 2014 | Belgium Netherlands |

14 | 15-49 | Not interviewed | IDI | Inductive analysis | Sexual health determinants |

| Themes | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| 3.1 The need to focus emergency care on SRH | 3.1.1 IMW: victims of trafficking and sexual exploitation. |

| 3.1.2 The need to develop suitable safety protocols. | |

| 3.2. Unsatisfactory clinical experiences | 3.2.1 The need for interpreters. |

| 3.2.2 Healthcare providers’ lack of cultural competence. | |

| 3.3 Forced reproduction | 3.3.1 Practices that put the IMW’s personal health at risk. |

| 3.3.2 Pregnancies characterised by the IMW’s irregular status. | |

| 3.3.3 Unsafe sex life. | |

| 3.4 Alternating between formal and informal healthcare services. | 3.4.1 Access to information and care. |

| 3.4.2 Unsafe abortions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).