1. Introduction

A game is symmetric if all players have the same strategy set and the payoff of a given strategy is determined merely by the strategy itself and has nothing to do with who plays it. Symmetric games have been widely studied since the dawn of game theory, and together with zero-sum games, they form one of the most classical subclasses of games. For example, Nash [

1,

2] proposed a very important concept of equilibrium, called Nash equilibrium, which is a strategy profile in which each player’s strategy is an optimal response to the strategies of the other players. This concept has a nice property that there is at least one Nash equilibrium for every finite game, and every finite symmetric game leads to a symmetric Nash equilibrium (an equilibrium in which all players use the same strategy) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Some researchers were devoted to symmetric games; for additional statements, one can refer to [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

The symmetric game, in particular, is important in the study of economic and biological models [

16,

17,

18,

19]. As we know, many interactions have been modeled in terms of one-shot and some of them have been reported as symmetric two-player cooperative dilemmas, including the Prisoner’s Dilemma [

20,

21], Hawk Dove Game [

21], Snowdrift Game [

22], and Stag-Hunt Game [

23]. If each player has

n actions to choose in a 2-player symmetric game, the game can be represented by two

n-by-

n matrices [

24,

25]. It is known that the 2-player symmetric game can be formulated as a linear complementary problem. The Lemke-Howson algorithm [

24] is a well known method which was designed to solve the above mentioned linear complementary problem.

However, in many real-life situations, decisions are made by groups of people that include more than two individuals [

19]. This type of collective action problem is better to be described as an

m-person symmetric game [

26,

27,

28]. We prefer to find symmetric equilibria for an

m-person symmetric game because asymmetric behavior appears relatively unintuitive [

6] and difficult to explain in a one-shot interaction [

29]. Nash proved that there is a symmetric equilibrium in every

m-person symmetric game [

2], but the Nash equilibrium equations for

m-person games are non-linear which are difficult to be solved analytically in general.

To better address the

m-person game, Huang and Qi [

30] extended the classic form of a game to a tensor form by using a tensor to represent the utility function of each player. They reformulated the

m-person game as a tensor complementary problem, and showed that finding a Nash equilibrium of the

m-person is equivalent to finding a solution to the resulting tensor complementary problem. Abdou et al. [

31] presented an efficient method to solve the pure Nash equilibrium by using tensor operations. However, they did not take the Nash equilibrium of a multiplayer symmetric game into consideration.

In this paper, we consider the tensor-based

m-person symmetric games. We demonstrate that the payoff tensors of the

k-th player in an

m-person symmetric game are

k-mode symmetric and that the payoff tensors between different players are the transpose of each other. We also reformulate the

m-person symmetric games as a tensor complementary problem. It is worth noting that the order of tensors in the tensor complementary problem is less than that resulting in [

30]. In addition, we show that finding a symmetric Nash equilibrium of the

m-person symmetric game is equivalent to finding a solution to the resulting tensor complementary problem. Finally, we apply a hyperplane projection algorithm to solve the resulting tensor complementary problem and provide some numerical results for solving the symmetric Nash equilibrium.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: In

Section 2, we present some definitions and notations that will be frequently used in the following parts. In

Section 3, we provide a brief description of the

m-person symmetric game. Some experimental results that can be used to explain our proposed theory’s reliability are shown in

Section 4. Finally, we provide a brief summary in

Section 5.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we introduce some definitions and notations, which will be used in the sequel. Throughout this paper, we use small letters (e.g.,a), small bold letters (e.g.,), capital letters (e.g.,A), and calligraphic letters (e.g.,) to denote scalars, vectors, matrices, and tensors, respectively. For a positive integer n, let .

A real

m-th order

-dimensional tensor is a multidimensional array, and its elementwise form can be denoted as

When , is an -by- matrix. If , is called a real m-th order n-dimensional tensor. We denote the set of all real m-th order -dimensional tensors by and denote the set of all real m-th order n-dimensional tensors by . When , is simplified as , which is the set of all n-dimensional real vectors. We denote the set of all nonnegative n-dimensional real vectors by . Let , , and 0 denote the n-dimensional vector of all ones, the i-th column of the n-dimensional identity matrix, and the zero vector, respectively. The order ⩾ means that each component of is nonnegative.

The definition of the k-mode product of a tensor with a vector is recalled as follows.

Definition 1. [

32]

The k-mode (vector) product of a tensor multiplied by a vector is denoted by , which leads to a real -th order -dimensional tensor with

for any with .

Let

and

with

. According to Definition 1, it follows that

where

is an

-dimensional vector with entries

For simplicity of notion, we use

to denote the scale

and use

to denote the real

-dimensional vector

Particularly, when

, and

, we take the symbols

,

, and

to denote the scales

and

respectively. The symbol

is short for the

n-dimensional vector

.

The definitions of symmetric and semi-symmetric tensors are given as follows.

Definition 2. [

33,

34]

A tensor is called symmetric, if

where is the set of permutations of length m.

Definition 3. [

32]

A tensor is called semi-symmetric, if for any ,

We provide a more general definition about k-mode symmetric of a tensor.

Definition 4.

A tensor is called k-mode symmetric, if for any ,

Remark 1. When , is 1-mode symmetric if and only if is semi-symmetric. An m-th order n-dimensional tensor has independent entries. If is k-mode symmetric, then has n independent entries. If is symmetric, then has only independent entries.

By Definitions 1, 2, and 4, we have the following lemma.

Lemma 1. Let . Then is k-mode symmetric if and only if is a symmetric tensor for all .

Proof. From Definition 1, we get

which implies that for all

,

if and only if

According to Definitions 2 and 4, it comes with that is k-mode symmetric if and only if is a symmetric tensor for all . □

In [

35], the definition of transpose of a tensor was introduced as follows:

Definition 5. [

35]

Let and . The σ-transpose of is an m-th order n-dimensional tensor, denoted by , with entries

Remark 2. When , is an n-by-n matrix. Let with and , then reduces to its matrix transpose.

We recall the psdudomonotone mapping and projection operator, which will be used in

Section 4.

Definition 6. A mapping is said to be pseudomonotone on if for every x and y in , and it follows that if is true then is true.

Definition 7.

Let be a nonempty convex subset of . denotes the projection operator that maps from to and is defined as

where is -norm in .

Remark 3.

When , is simplified as . The projection operator can be computed as follows

where the max operator denotes the componentwise maximum of two vectors.

3. Description of the m-person symmetric game

In this section, we first provide the definition of a tensor form of an

m-person game, adapted from [

30] and [

31].

Definition 8. [

30,

31]

An m-person game in a tensor form is a tuple

where is the set of players, is the pure strategy set of player k, is the payoff tensor of player k, that is, for any with any , if the player 1 plays his -th pure strategy, the player 2 plays his -th pure strategy, ⋯, and the player m plays his -th pure strategy, then the payoffs of player 1, player 2, ⋯, and player m are , , ⋯, and , respectively.

Given an

m-person game

. A mixed strategy of player

k is the probability distribution on pure strategy set

. Let

denote the set of the all probability distributions on

. For

, the probability assigned to

-th pure strategy of player

k is

.

Using

denote the set of strategy profiles. We say that

is a mixed strategy combination if

is a mixed strategy of player

k for any

. If a mixed strategy combination

is played, then the expected payoff of player

k is

Definition 9. [

2,

30]

A mixed strategy combination is a Nash equilibrium of the m-person game, if for each strategy combination and , it holds that

What we consider here is the m-person symmetric games. In such games, all players play the same role in the game and moreover the payoff of any player depends only upon its strategy and the combination of the strategies of its opponents.

Definition 10.

An m-person game is symmetric if the players have identical pure strategy set, that is , and every payoff tensor satisfies

where is the inverse of the permutation σ.

It is well know that the payoff matrices of the 2-person symmetric game are transpose of each other [

20]. Furthermore, we come to a similar conclusion for the

m-person symmetric game.

Theorem 1. Suppose that be an m-person game. Then G is symmetric if and only if

- (i)

is k-mode symmetric for all ;

- (ii)

if , then , for all satisfies .

Proof. Firstly, we show the necessity. By Definition 10, it comes with

. Combing it with Definition 1, we have

Let

be a permutation on set

and

satisfies

By (

1) and Definition 10, we have

Therefore, is a symmetric tensor for all . By Lemma 1, is k-mode symmetric. Hence, the statement (i) holds.

Since

satisfies

. From Definition 5, we have

which implies

. Hence, the statement (ii) holds.

Now, we show the sufficiency. It is comes to for is k-mode symmetric. For any and fixed index j, we have or . To prove our statement we have to talk about it in the following two cases.

Case 1:

. Let

be a permutation on set

that satisfies

. Since

is

k-mode symmetric, we have

Case 2:

. According to

, we obtain

By Definition 10, we have is an m-person symmetric game. □

Remark 4. (I) Consider the m-player Volunteer’s Dilemma[

36,

37]

, m individuals observe an approaching predator and need to decide whether or not to sound the alarm, independently and without coordination. If an individual alarms, the predator’s ambush may be ruined. Each individual has two choices: volunteer (alarm) or ignore (no alarm). An alarm call would benefit everyone because it would deter the predator from attacking again; each player, however, prefers that the other players report the presence of the predator because giving the alarm has a cost . If one sets the alarm, he has a payoff of , while the others who do not set the alarm have a payoff of b. If nobody raises the alarm, the predator attacks, inflicting damage and a payoff of on everyone. Herein, we use the digits “1” and “2" to denote the alarm and non-alarm strategies, respectively. Therefore, the tensor form of the m-player Volunteer’s Dilemma can be represented as , where

By calculation, we get that the statements (i) and (ii) of Theorem 1 are held. Therefore, the m-player Volunteer’s Dilemma is symmetric.

(II) From Theorem 1

, we have the first player’s payoff tensor is 1-mode symmetric. The payoffs in m-person symmetric games are uniquely determined by the first player’s payoff tensor . Therefore, in the rest of this paper, we denote an m-person symmetric game by the tuple , and let

Definition 11. [

2]

A Nash equilibrium is symmetric if all players take the same strategy, that is, .

Nash proved the existence of equilibrium for

m-person games and symmetric equilibrium for symmetric

m-person games in 1951 [

2], and the statement is summarized in the following Lemma.

Lemma 2. [

2]

Every m-person symmetric game has a symmetric Nash equilibrium.

Now, we are going to propose two equivalent conditions to ensure that a mixed strategy combination is a symmetric Nash equilibrium, which are shown in Theorems 2 and 3.

Lemma 3.

Suppose that be an m-person symmetric game, then is a symmetric Nash equilibrium if and only if is an optimal solution to the following optimization problem,

Proof. By Definition 9,

is a symmetric Nash equilibrium if and only if for any strategy combination

and any

, namely,

Let

with

, and

for all

. By Definition 1, we have

and

Together with Theorem 1, we can get

. Therefore, the inequality (

3) is equivalent to

The proof is completed. □

Let

where

and

is an

m-th order

n-dimensional tensor whose all entries are ones. According to

is 1-mode symmetric we can see that

is also a 1-mode symmetric tensor with all entries are positive.

Theorem 2.

Suppose that be an m-person symmetric game, and is defined as (

4)

, then is a symmetric Nash equilibrium if and only if is an optimal solution to the following optimization problem:

Proof. For any mix strategy

, we have

Therefore,

is an optimal solution to the optimization problem (

5) if and only if

is an optimal solution to the optimization problem (

2). □

We consider the following model: Find a mixed strategy combination

such that

is an optimal solution to the optimization problem (

5). Given a tensor

and a vector

, the tensor complementary problem, denoted by TCP

, is to find a vector

such that

The TCP

was introduced by Song and Qi [

38] and was further studied by many researchers [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. The tensor complementary problem is a generalization of the linear complementary problem (corresponding to

) [

49] and also a special instance of a nonlinear complementary problem, as well as a particular case of a variational inequality problem corresponding to the close convex cone

[

50]. Denote the solution set of the TCP(

) by SOL(

). In this section, we show that the

m-person symmetric game can be reformulated as a specific tensor complementary problem.

Let

be an

m-person symmetric game and

defined as (

4). We construct a tensor complementary problem as follows,

There is an explicit corresponding relation between the solutions of a symmetric Nash equilibrium of the

m-person symmetric game and a solution to the TCP

(

7).

Theorem 3.

Suppose that be an m-person symmetric game and defined as (

4)

. If is a symmetric Nash equilibrium of the game , then SOL

, where

Conversely, if SOL

, then and with

is a symmetric Nash equilibrium of the game .

Proof. Firstly, we show the necessity. Suppose that

is a symmetric Nash equilibrium of the

m-person symmetric game

. By the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker conditions of problem (

5), there exist a number

and a nonnegative vector

such that

and

By (

10), we have

which together with (

11) it yields

According to (

10), we obtain

Combing (

13) with (

11), we get

Apply the results of (

13) and (

14) to (

12) we obtain that

defined by (

8) is a solution to the TCP

. That is,

.

Now, we show the sufficiency. Suppose that

, then

By the first and second inequalities of (

15), we have

. Next, we prove that

defined by (

9) is a symmetric Nash equilibrium of the

m-person symmetric game

. For this purpose, we need to prove that there exists a number

and a nonnegative vector

such that (

10) and (

11) hold.

We get the following equation from the iequalities of (

15).

Since

and

follow, this implies that

follows, and then

By (

9), the above equality becomes

From

,

, and the definition of

, it follows that

and

. In addition, by the second inequality of (

15), we have

which implies that there exists a nonnegative vector

such that

The above result together with (

16), yields

So, we obtain that (

10) and (

11) hold with

Therefore,

defined by (

9) is a symmetric Nash equilibrium of the

m-person symmetric game

. □

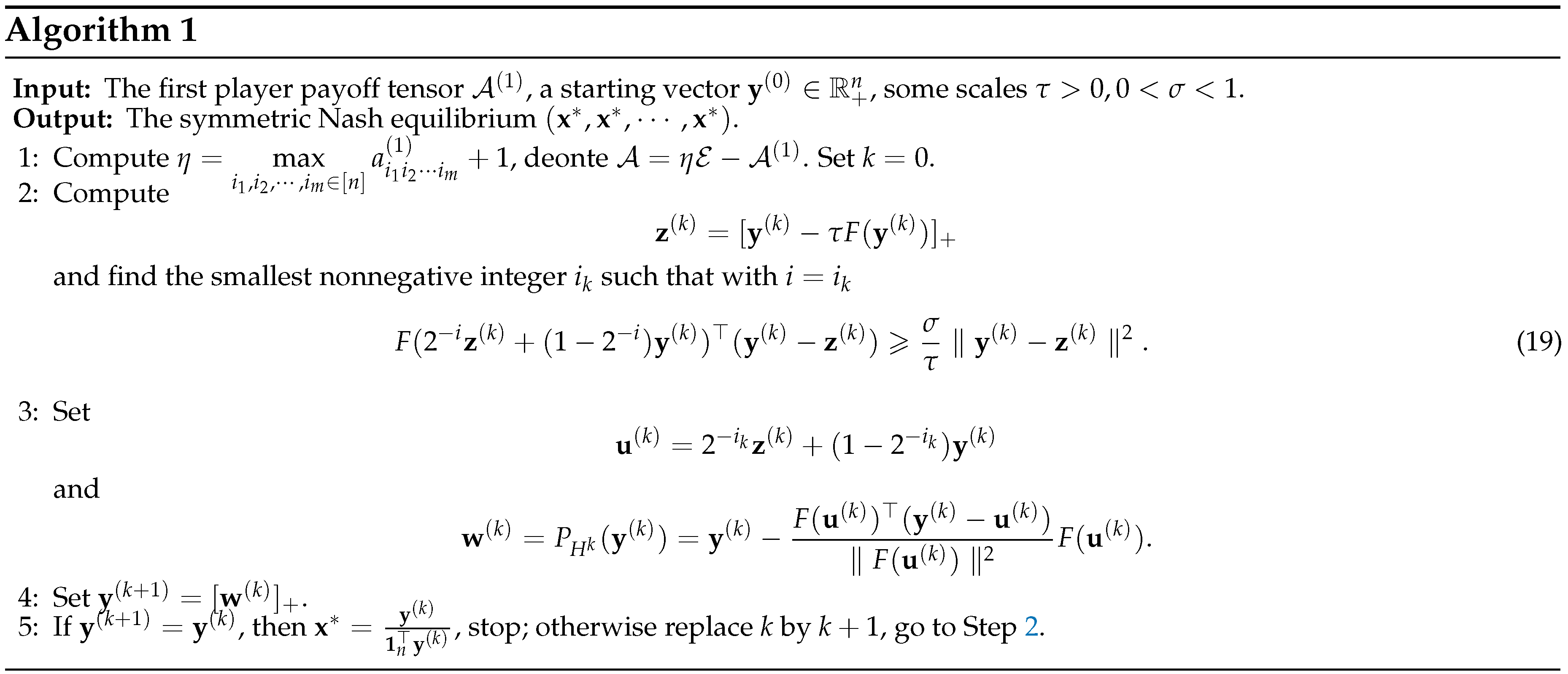

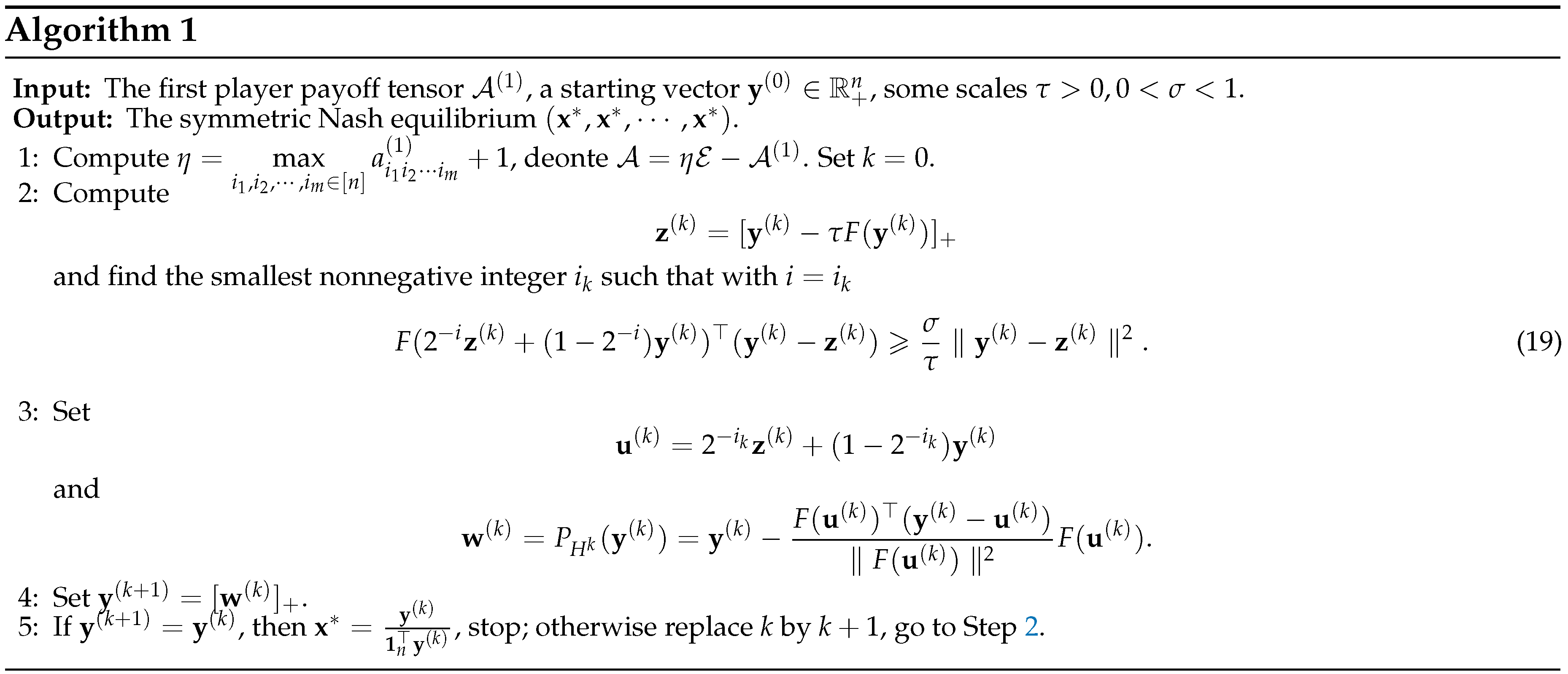

4. Algorithm and numerical results

It is well known that the hyperplane projection algorithm [

50] is a class of effective methods for solving variational inequalities and complementary problems. In this section, we apply the hyperplane projection algorithm to solve the TCP

and provide some preliminary numerical results for solving the

m-person symmetric game.

Let

be an

m-person symmetric game and

defined as (

4). Denote

, then we can rewrite the TCP

(

7) as follows,

It is well know that (

17) is equivalent to the variational inequality problem: Find a nonnegative vector

such that

and it is equivalent to finding a root of the following equations

We use the hyperplane projection algorithm, see Algorithm 1, to solve the problem (

17), which can be described geometrically as follows. Let

be a fixed scale, and

is a given vector. Firstly, we compute the point

. Secondly, based on the Armijo-type search routine, we search the line segment joining the

and

and get a point

such that the hyperplane

strictly separates

from SOL

. We project

onto

and get a point

, and project the point

onto

, then

is obtained. It can be shown that

is closer to SOL

than

[

50].

From [

50], we obtain the following theorems.

Theorem 4.

Suppose that is not a solution to the TCP(

17)

. Then there exists a finite integer such that (19) holds and

Remark 5.

If is pseudomonotone on , the inequality (20)

shows that the hyperplane strictly separates from SOL. Based on and the inequality(

18)

, it follows that for any solution of the TCP, we have

Based on the fact that is pseudomonotone on , then combing (20)

and (21)

it yields

Theorem 5.

Suppose that is pseudomonotone on , then there exists such that

In the following, we give some preliminary numerical results of Algorithm 1 for solving the symmetric Nash equilibrium of the

m-person symmetric game. Throughout our experiments, the parameters used in Algorithm 1 are chosen as

We use as the stopping rule. All tests are conducted in MATLAB R2015a with the configuration: Intel(R) Core(TM)i7-7500U CPU 2.70GHz and 8.00G RAM.

Example 1.

According to Remark 4

. The tensor form of the m-player Volunteer’s Dilemma can be represented as , where

We use Algorithm 1

to solve the symmetric Nash equilibrium of the m-player Volunteer’s Dilemma and the numerical results are reported in Table 1. In this table, the number of iteration steps are denoted by No.Iter, the CPU time in seconds are denoted by CPU(s). As the algorithm stops the value of is computed and denoted by Res and the first player’s strategy in symmetric Nash equilibrium is denoted by SNE().

Example 2.

In the m-player Snowdrift Game [

51]

, m individuals are driving on a crossroad that is blocked by a snowdrift. Each individual has the option to cooperate by shoveling the snow or not. The snow need to be removed before they continue their journey home. Again, everyone wants to go home, but not everyone is willing to shovel. If the benefit of getting home is defined as b and the cost of shoveling is defined as c. Assuming that the benefit exceeds the cost, i.e., . If everyone shovels, then everyone gets . But if only k individuals shovel, they get whereas those who refuse to shovel get home for free and get b. Nobody gets anything if everyone refuses to shovel. Let 1 and 2 denote the shovel snow and do not shovel snow strategies, respectively. It is easy to obtain that the m-player Snowdrift Game is symmetric. Let denote the number of 1 in . The tensor form of the m-player Snowdrift Game can be represented as , where

We use Algorithm 1

to solve the symmetric Nash equilibrium of m-player Snowdrift Game. The numerical results are reported in Table 2, where No.Iter, CPU(s), Res and SNE are the same as those used in Table 1.

Example 3.

Consider the bimatrix symmetric game “Rock-Paper-Scissors”[

9,

52]

. The tensor form of “Rock-Paper-Scissors” can be represented as , where

We use Algorithm1

to solve the symmetric Nash equilibrium of “Rock-Paper-Scissors”. A symmetric Nash equilibrium with

is obtained with 23 iteration steps in 0.2921 seconds.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we show that the payoff tensor of the kth player in an m-person symmetric game is k-mode symmetric, and the payoff tensors of two different individuals are the transpose of each other. We also reformulate the m-person symmetric games as tensor complementary problems and demonstrate that finding a symmetric Nash equilibrium of the m-person symmetric game is equivalent to finding a solution to the resulting tensor complementary problem. Finally, we apply the hyperplane projection algorithm to solve the resulting tensor complementary problem and provide some numerical results for solving the symmetric Nash equilibrium.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q. Liu and Q. Liao; methodology, Q. Liu and Q. Liao; software, Q. Liu; writing—original draft preparation, Q. Liu; writing—review and editing, Q. Liao. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by the Natural Science Foundation of the Educational Commission of Guizhou Province under Grant Qian-Jiao-He KY Zi [2021]298 and Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects under Grant QKHJC-ZK[2023]YB245.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nash, J. Equilibrium points in n-person games. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1950, 36, 48–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, J. Non-cooperative games. Ann. Math. 1951, 54, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Wu, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. Finding Nash equilibrium for imperfect information games via fictitious play based on local regret minimization. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 6152–6167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelsen, M.L.T.; Hansen, K.A. On the computational complexity of decision problems about multi-player Nash equilibria. Theor. Comput. Syst. 2022, 66, 519–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, G. Evolutionary stable strategies and game dynamics for n-person games. J. Math. Biol. 1984, 19, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, D.M. Game theory and economic modelling; Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Von Stengel, B. Computing equilibria for two-person games. Handbook of game theory with economic applications 2002, 3, 1723–1759. [Google Scholar]

- Govindan, S.; Wilson, R. A global Newton method to compute Nash equilibria. J. Econ. Theory 2003, 110, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.F.; Reeves, D.M.; Vorobeychik, Y.; Wellman, M.P. Notes on equilibria in symmetric games 2004. pp. 71–78.

- Roughgardenl, T. Computing equilibria in multi-player games. Proceedings of the Sixteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms. SIAM, 2005, Vol. 118, p. 82.

- Amir, R.; Jakubczyk, M.; Knauff, M. Symmetric versus asymmetric equilibria in symmetric supermodular games. Int. J. Game Theory 2008, 37, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefti, A. Equilibria in symmetric games: Theory and applications. Theor. Econ. 2017, 12, 979–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reny, P.J. Nash equilibrium in discontinuous games. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2020, 12, 439–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilò, V.; Mavronicolas, M. The complexity of computational problems about Nash equilibria in symmetric win-lose games. Algorithmica 2021, 83, 447–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armony, M.; Roels, G.; Song, H. Capacity choice game in a multiserver queue: Existence of a Nash equilibrium. Nav. Res. Log. 2021, 68, 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomze, I.M. Non-cooperative two-person games in biology: A classification. Int. J. Game Theory 1986, 15, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myerson, R.B. Nash equilibrium and the history of economic theory. J. Econ. Lit. 1999, 37, 1067–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.M. Evolutionary game theory. Physica D. 1986, 22, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, M.; Rychtár, J. Game-theoretical models in biology; CRC Press, 2013.

- Rapoport, A.; Chammah, A.M.; Orwant, C.J. Prisoner’s dilemma: A study in conflict and cooperation; Vol. 165, University of Michigan press, 1965.

- Axelrod, R.; Hamilton, W.D. The evolution of cooperation. Sci. 1981, 211, 1390–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugden, R.; others. The economics of rights, co-operation and welfare; Springer, 2004.

- Skyrms, B. The stag hunt and the evolution of social structure; Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Lemke, C.E.; Howson, Jr, J. T. Equilibrium points of bimatrix games. J. Soc. Indust. Appl. Math. 1964, 12, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, M.S.; Sznajder, R. A generalization of the Nash equilibrium theorem on bimatrix games. Int. J. Game Theory 1996, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R. Computing equilibria of n-person games. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1971, 21, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.O.; Pacheco, J.M.; Santos, F.C. Evolution of cooperation under N-person snowdrift games. J. Theor. Biol. 2009, 260, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.D.; Pinheiro, F.L.; Santos, F.C.; Pacheco, J.M. Dynamics of N-person snowdrift games in structured populations. J. Theor. Biol. 2012, 315, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenschein, J.S.; Zlotkin, G. Rules of encounter: designing conventions for automated negotiation among computers; MIT press, 1994.

- Huang, Z.; Qi, L. Formulating an n-person noncooperative game as a tensor complementarity problem. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2017, 66, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, J.; Safatly, E.; Nakhle, B.; Khoury, A.E. High-dimensional nash equilibria problems and tensors applications. Int. Game Theory Rev. 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolda, T.G.; Bader, B.W. Tensor decompositions and applications. SIAM Rev. 2009, 51, 455–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofidis, E.; Regalia, P.A. On the best rank-1 approximation of higher-order supersymmetric tensors. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 2002, 23, 863–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L. Eigenvalues of a real supersymmetric tensor. J. Symb. Comput. 2005, 40, 1302–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnarsson, S.; Van Loan, C.F. Block tensors and symmetric embeddings. Linear Algebra Appl. 2013, 438, 853–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murnighan, J.K.; Kim, J.W.; Metzger, A.R. The volunteer dilemma. Admin. Sci. Quart. 1993, pp. 515–538.

- Archetti, M. The volunteer’s dilemma and the optimal size of a social group. J. Theor. Biol. 2009, 261, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Qi, L. Properties of some classes of structured tensors. J. Optimiz. Theory App. 2015, 165, 854–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y. Global uniqueness and solvability for tensor complementarity problems. J. Optimiz. Theory App. 2016, 170, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, M.; Qi, L.; Wei, Y. Positive-definite tensors to nonlinear complementarity problems. J. Optimiz. Theory App. 2016, 168, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Luo, Z.; Qi, L. P-tensors, P0-tensors, and their applications. Linear Algebra Appl. 2018, 555, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Qi, L.; Xiu, N. The sparsest solutions to Z-tensor complementarity problems. Optim. Lett. 2017, 11, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Qi, L. Tensor complementarity problem and semi-positive tensors. J. Optimiz. Theory App. 2016, 169, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Qi, L. Properties of tensor complementarity problem and some classes of structured tensors. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.0113 2014.

- Xie, S.; Li, D.; Hongru, X. An iterative method for finding the least solution to the tensor complementarity problem. J. Optimiz. Theory App. 2017, 175, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; He, H.; Ling, C. On error bounds of polynomial complementarity problems with structured tensors. Optimization 2018, 67, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yu, G. Properties of solution set of tensor complementarity problem. J. Optimiz. Theory App. 2016, 170, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Bai, X. Exceptionally regular tensors and tensor complementarity problems. Optimi. Method. Softw. 2016, 31, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottle, R.; Pang, J.; Stone, R. The linear complementarity problem, 1992.

- Facchinei, F.; Pang, J. Finite-dimensional variational inequalities and complementarity problems, Volume II; Springer Science & Business Media, 2007.

- Souza, M.O.; Pacheco, J.M.; Santos, F.C. Evolution of cooperation under N-person snowdrift games. J. Theor. Biol. 2009, 260, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinervo, B.; Lively, C.M. The rock–paper–scissors game and the evolution of alternative male strategies. Nature 1996, 380, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

The numerical results of the problem in Example 1

Table 1.

The numerical results of the problem in Example 1

| m |

b |

a |

c |

No.Iter |

CPU(s) |

Res |

SNE

|

| 3 |

200 |

4 |

1 |

10 |

0.0582 |

4.18e-7 |

(0.5000,0.5000) |

| |

|

4 |

2 |

41 |

0.2277 |

9.99e-7 |

(0.2929,0.7071) |

| |

|

16 |

2 |

47 |

0.2644 |

7.62e-7 |

(0.6465,0.3235) |

| |

|

32 |

1 |

50 |

0.3912 |

7.42e-7 |

(0.8232,0.1768) |

| |

|

64 |

3 |

21 |

0.1919 |

9.82e-7 |

(0.7835,0.2165) |

| |

|

192 |

3 |

72 |

0.6176 |

9.19e-7 |

(0.8750,0.1250) |

| 6 |

200 |

4 |

1 |

121 |

0.8751 |

9.18e-7 |

(0.2422,0.7578) |

| |

|

4 |

2 |

101 |

0.7523 |

9.17e-7 |

(0.1295,0.8705) |

| |

|

16 |

2 |

63 |

0.5111 |

8.43e-7 |

(0.3403,0.6597) |

| |

|

32 |

1 |

9 |

0.1503 |

3.53e-7 |

(0.5000,0.5000) |

| |

|

64 |

3 |

11 |

0.0818 |

3.54e-7 |

(0.4578,0.5422) |

| |

|

192 |

3 |

14 |

0.1152 |

4.32e-7 |

(0.5647,0.4353) |

| 9 |

600 |

64 |

0.25 |

14 |

0.1891 |

5.95e-7 |

(0.5000,0.5000) |

| |

|

64 |

0.5 |

59 |

0.5382 |

8.54e-7 |

(0.4548,0.5452) |

| |

|

64 |

1 |

30 |

0.2826 |

5.90e-7 |

(0.4054,0.5946) |

| |

|

512 |

0.25 |

88 |

0.7381 |

8.84e-7 |

(0.6145,0.3855) |

| |

|

512 |

0.5 |

77 |

0.7354 |

6.79e-7 |

(0.5796,0.4204) |

| |

|

512 |

1 |

54 |

0.6315 |

7.15e-7 |

(0.5415,0.4585) |

| 12 |

600 |

64 |

0.25 |

206 |

2.1890 |

9.43e-7 |

(0.3960,0.6040) |

| |

|

64 |

0.5 |

143 |

1.8373 |

9.61e-7 |

(0.3567,0.6433) |

| |

|

64 |

1 |

114 |

1.2770 |

9.67e-7 |

(0.3149,0.6851) |

| |

|

512 |

0.25 |

11 |

0.5486 |

5.97e-7 |

(0.5000,0.5000) |

| |

|

512 |

0.5 |

53 |

0.7763 |

9.67e-7 |

(0.4675,0.5325) |

| |

|

512 |

1 |

27 |

0.5974 |

8.64e-7 |

(0.4329,0.5671) |

| 15 |

2500 |

2048 |

0.125 |

8 |

3.1455 |

3.90e-7 |

(0.5000,0.5000) |

| |

|

2048 |

64 |

63 |

3.6172 |

4.56e-7 |

(0.2193,0.7807) |

| |

|

2048 |

128 |

65 |

3.8518 |

9.35e-7 |

(0.1797,0.8203) |

| |

|

1024 |

0.125 |

177 |

4.6659 |

9.93e-7 |

(0.4747,0.5253) |

| |

|

1024 |

64 |

47 |

3.3835 |

8.62e-7 |

(0.1797,0.8203) |

| |

|

1024 |

128 |

85 |

4.4102 |

7.11e-7 |

(0.1380,0.8620) |

Table 2.

The numerical results of the problem in Example 2

Table 2.

The numerical results of the problem in Example 2

| m |

b |

c |

No.Iter |

CPU(s) |

Res |

SNE

|

| 3 |

8 |

1 |

71 |

0.3320 |

8.84e-7 |

(0.7686,0.2314) |

| |

8 |

2 |

34 |

0.1822 |

8.49e-7 |

(0.6496,0.3504) |

| |

10 |

5 |

26 |

0.1606 |

8.69e-7 |

(0.4418,0.5582) |

| |

10 |

8 |

161 |

0.8231 |

8.92e-7 |

(0.1886,0.8114) |

| |

20 |

1 |

20 |

0.1729 |

9.22e-7 |

(0.8611,0.1389) |

| |

20 |

10 |

27 |

0.1719 |

7.46e-7 |

(0.4417,0.5583) |

| 6 |

8 |

1 |

136 |

0.8696 |

8.79e-7 |

(0.4653,0.5347) |

| |

8 |

2 |

134 |

0.7635 |

9.08e-7 |

(0.3595,0.6405) |

| |

10 |

5 |

132 |

0.8305 |

9.62e-7 |

(0.2162,0.7838) |

| |

10 |

8 |

157 |

0.9867 |

8.08e-7 |

(0.0817,0.9183) |

| |

20 |

1 |

92 |

0.5705 |

8.62e-7 |

(0.5711,0.4289) |

| |

20 |

10 |

92 |

0.6909 |

7.21e-7 |

(0.2162,0.7838) |

| 9 |

8 |

1 |

95 |

0.7384 |

2.12e-7 |

(0.3291,0.6709) |

| |

8 |

2 |

68 |

0.5151 |

8.84e-7 |

(0.2466,0.7534) |

| |

10 |

5 |

59 |

0.4447 |

3.20e-7 |

(0.1436,0.8574) |

| |

10 |

8 |

84 |

0.7784 |

8.17e-7 |

(0.0520,0.9480) |

| |

20 |

1 |

164 |

1.2335 |

9.53e-7 |

(0.4179,0.5821) |

| |

20 |

10 |

56 |

0.5454 |

4.96e-7 |

(0.1426,0.8574) |

| 12 |

8 |

1 |

370 |

3.4376 |

9.99e-7 |

(0.2542,0.7458) |

| |

8 |

2 |

283 |

2.6579 |

9.51e-7 |

(0.1876,0.8124) |

| |

10 |

5 |

191 |

1.8678 |

7.55e-7 |

(0.1065,0.8935) |

| |

10 |

8 |

198 |

1.9516 |

7.56e-7 |

(0.0383,0.9617) |

| |

20 |

1 |

319 |

3.0998 |

9.39e-7 |

(0.3283,0.6717) |

| |

20 |

10 |

161 |

1.5762 |

9.82e-7 |

(0.1066,0.8934) |

| 15 |

8 |

1 |

357 |

6.1214 |

9.91e-7 |

(0.2068,0.7932) |

| |

8 |

2 |

249 |

5.3642 |

9.38e-7 |

(0.1512,0.8488) |

| |

10 |

5 |

199 |

4.5910 |

9.94e-7 |

(0.0850,0.9150) |

| |

10 |

8 |

214 |

4.7155 |

8.20e-7 |

(0.0304,0.9696) |

| |

20 |

1 |

338 |

6.1258 |

9.69e-7 |

(0.2699,0.7301) |

| |

20 |

10 |

180 |

4.7217 |

9.65e-7 |

(0.0850,0.9150) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).