1. Introduction

Bisphenol A (BPA), as an industrial raw material, is mainly used in the production of epoxy and polysulfide resins [

1]. BPA is also widely applied in commercial products, especially food contact materials, such as plastics, coatings of food cans, thermal papers and baby bottles [

2,

3,

4]. BPA can migrate from plastic bottles and cans to high-acid food, which can cause the food pollution [

5,

6]. Unfortunately, as a kind of endocrine disrupting chemicals, BPA can mimic estrogen, and many studies have demonstrated that the exposure to BPA was related to multiple irreversible damage to human body [

7]. Therefore, it is of great practical significance to found a convenient and accurate method to detect BPA.

The commonly methods used to detect BPA include liquid chromatography [

8], gas chromatography [

9], spectrophotometry [

10], immunoassays [

11] and fluorimetry [

12,

13]. Although these analytical techniques are mature for BPA detection, they still have many shortcomings, such as high cost, professional operation and complicated sample pretreatment [

14]. Hence, it is significant to found more convenient methods for BPA determination. Electrochemical sensor is regarded as an ideal method for BPA determination because of many merits such as low cost, fast analysis speed, high sensitivity, simplicity and easy miniaturization. For example, Xu et al. designed the electrochemical biosensor based on graphdiyne for the detection of BPA [

15]. However, the construction of electrochemical sensors is often based on some biomolecules, such as DNA, enzyme, protein, etc. These sensors mainly rely on the catalytic capacity of biomolecules. Nevertheless, these biomolecules always suffer from some inherent weaknesses such as expensive, hard to preserve and ease of denaturation, which seriously hinder the application in real sample detection [

16,

17].

It is crucial to choose suitable electrode material for improving the performances of electrochemical sensor. Nanozyme, a kind of synthetic nanomaterial with enzyme-like activity, which has attracted much attention due to its facile synthesis, tenability, favorable catalytic activity and low cost [

18,

19,

20]. Metal nanoparticles have attracted wide attention because of the effective catalytic activity similar to natural enzymes [

21]. Compared with single metal nanomaterials, trimetallic nanomaterials have higher specific surface area, superior catalytic activity and good stability due to the synergy effects between multiple elements [

22,

23,

24]. Therefore, trimetallic nanomaterials are considered as advanced nanozymes, which hold great promise in the field of electrochemical sensor. Additionally, Au, Pd, and Pt show excellent electrocatalytic activity and favorable conductivity. The combination of Au, Pd, and Pt shows synergistic effect to improve the properties of catalytic and further increase the sensitivity of sensor. [

25,

26]. For example, Barman et al. reported a AuPtPd nanocomposites on -COOH terminated graphene oxide for analysis of prostate biomarkers [

27], and Cen et al. introduced an immunosensor based on ultrasensitive label-free AuPtPd porous fluffy-like nanodendrites for detecting cardiac troponin I [

28]. In addition, multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) have vast applications in electrochemical fields for the large surface area and efficient electrons transfer which improves electrochemical activity and sensitivity of the electrochemical sensor.[

29] However, the stability of these individual nanomaterials on electrode surface is usually not very favorable. Hence, it is necessary to combine nanozyme with biological macromolecules to construct nanocomposites to improve the stability of electrochemical sensors.

Chitosan can be obtained from the deacetylation of chitin, is popularly used in combination with nanomaterials because of its good biocompatibility and excellent membrane-forming capacity, which makes it suitable for developing sensors [

30,

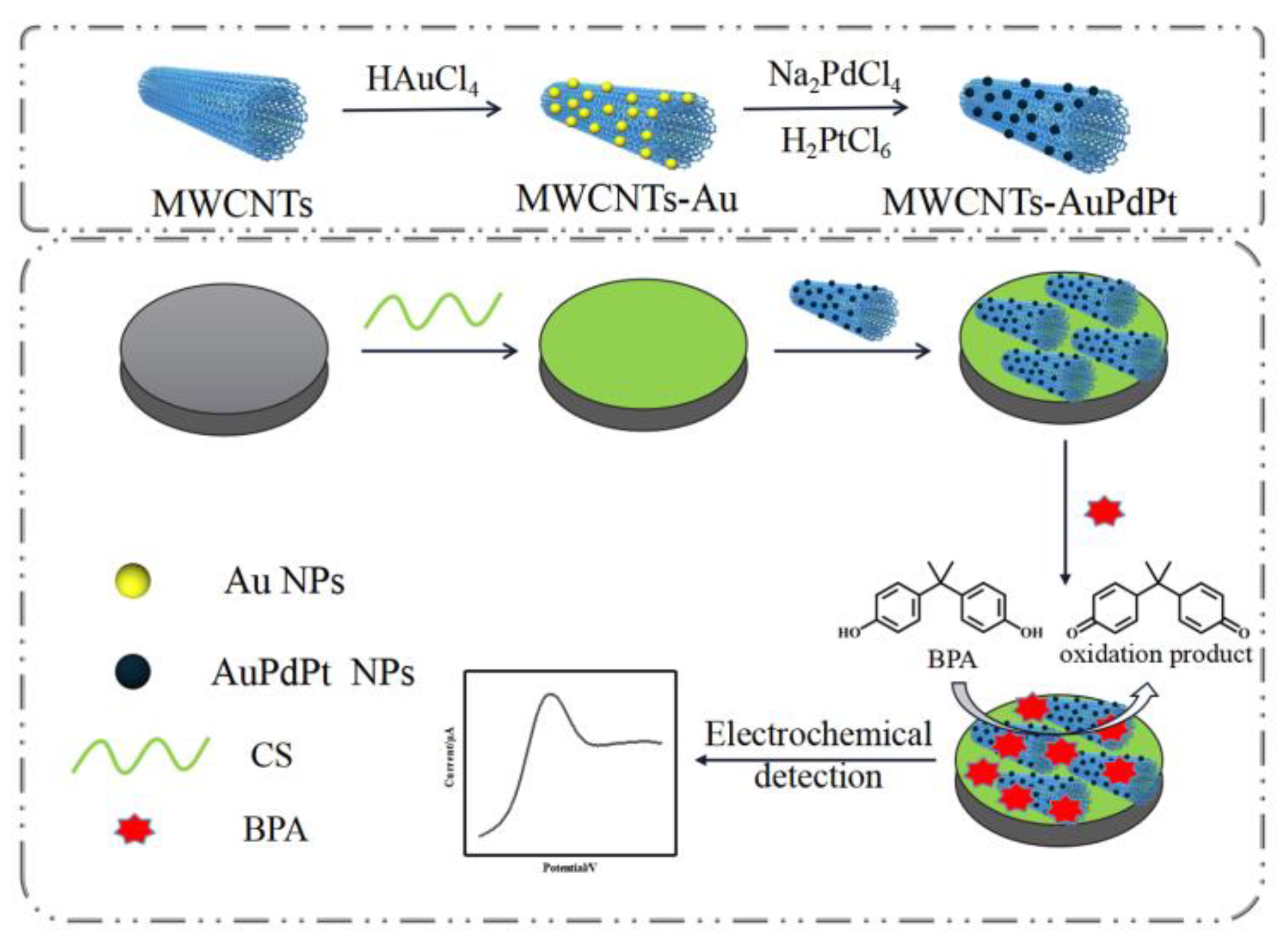

31]. Herein, a sensitive electrochemical sensor based on AuPtPd trimetallic nanoparticles functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes coupled with chitosan modified glassy carbon electrode (GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd) was proposed to realize the detection of BPA in food. The process of the electrochemical sensors was displayed in

Figure 1. AuPtPd were first assembled on the surface of MWCNTs to obtain MWCNTs-AuPtPd nanocomposites. Then MWCNTs-AuPtPd was further dispersed on the chitosan modified electrode surface to form GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd sensor. The features of the nanocomposites were investigated such as structural morphology, optical properties and electrochemical behavior. The effect of buffer pH, concentrate of MWCNTs-AuPtPd and accumulation time were optimized to obtain the optimum experiment conditions for BPA determination. DPV was used to study the performances of the prepared sensor, and the results showed that the nanocomposites of CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd had good electrochemical response to BPA, which was reliable for the rapid detection of BPA in actual food samples.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

Tetrachloroauric (III) acid tetrahydrate (HAuCl4·4H2O), chloroplatinic acid hexahydrate (H2PtCl6·6H2O), sodium tetrachloropalladate (Na2PdCl4), ascorbic acid (AA), trisodium citrate, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP; K-30), potassium ferricyanide (K3Fe(CN)6), potassium hexacyanoferrate (K4Fe(CN)6), hydroquinone (HQ), catechol (CT), disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na2HPO4) and sodium dihydrogen phosphate (NaH2PO4) were bought from Shanghai Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co, Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) were bought by Xian Feng Nanotech Port Co, Ltd. (Nanjing, China).

2.2. Apparatus

Electrochemical experiments were conducted on CHI 660D electrochemical workstation (Chenhua Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) with a conventional three-electrode system. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained from JEM-2100 (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained from Quanta FEG 250 (FEI Ltd., Hillsboro, OR, USA). UV-vis was recorded by UV-1061.

2.3. Preparation of MWCNTs-AuPtPd

First, 0.1 g PVP and 20 mg MWCNTs were dispersed in 50 mL of HAuCl4 under constant stirring, and the mixture was heated to boiling. Then, 1 ml trisodium citrate (1%) was mixed to the above mixture. Two minutes later, 2 mL ascorbic acid (0.1 M) was mixed to the above solution, and subsequently added 50 mL Na2PdCl4 (0.6 mM) and 50 mL H2PtCl6 (0.6) mM to get a black mixture. Finally, the obtained mixture was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 10 min and washed with distilled water for 3 times, then, it was dispersed in ultrapure water and stored at 4 °C.

2.4. Preparation of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd

The bare electrode was polished by 0.3 μm alumina solution powder, then the electrode was cleaned by absolute ethanol and distilled water, and finally dried in air. Next, 8 μL of 1.5 mg ml-1 chitosan solution was transferred onto the electrode surface and waited for 1 hour. Then, 15 μL of 0.5 mg ml-1 MWCNT-AuPtPd dispersion was transferred onto the chitosan modified electrode surface and dried in air.

2.5. Analytical procedure

BPA was dissolved in a small amount of anhydrous ethanol. After dissolution, the BPA was diluted with PBS. Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) and cyclic voltammetry (CV) were conducted to characterize different modified electrodes. The voltage range of CVs was from -0.5 to 0.7 V in BPA solution and from -0.6 to 0.7 V in [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− solution with 50 mV s-1. DPV was performed from 0.1 to 0.9 V in BPA solution.

2.6. Sample detection

The samples of orange juice and milk were obtained from supermarket. The recoveries in actual samples were determined by standard addition method with various concentrations of BPA solution. The milk and orange juice were centrifugated for 5 min at 4000 rpm. The obtained solution was diluted with PBS solution (0.1M, pH 7.0) at a ratio of 9:1. Then, the samples were tested by using the designed method. Anti-interference test was carried out by detecting the mixture solution containing 0.1 mM BPA and interfering species (1 mM CT, 1 mM HQ, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl and 10 mM MgSO4).

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of the CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd nanocomposites

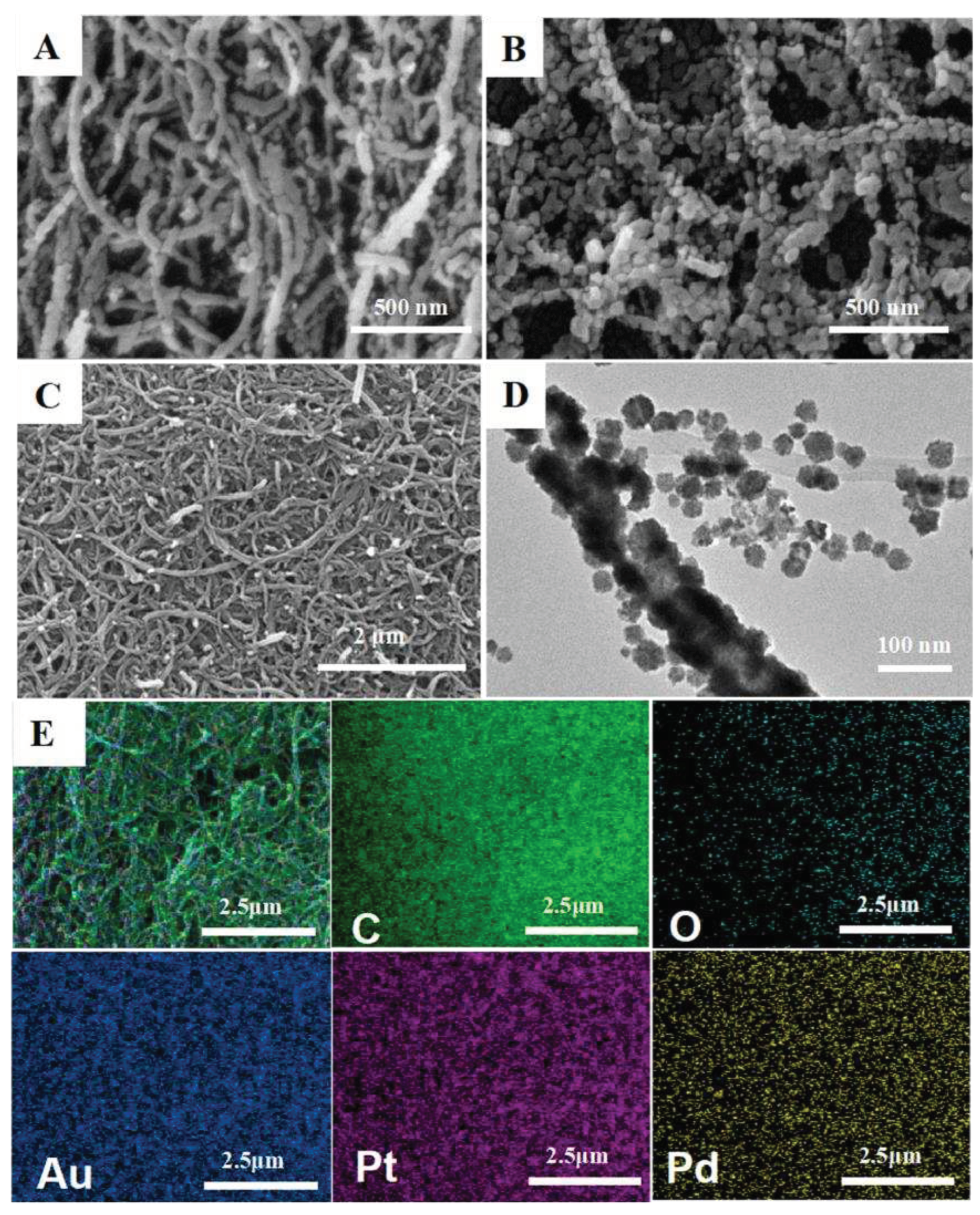

The morphologies of MWCNTs, MWCNTs-AuPtPd and CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd were characterized by SEM (

Figure 2A–C). Compared with MWCNTs (

Figure 2A), the diameters of MWCNTs-AuPtPd nanocomposites were larger than MWCNTs in

Figure 1B because of the assembled AuPtPd trimetallic nanoparticles on MWCNTs by in-situ growth method. The image of TEM was shown in

Figure 2D, which displayed that a great number of AuPtPd nanoparticles were uniformly formed on MWCNTs, indicating the successful fabrication of the MWCNTs-AuPdPt nanocomposites. As shown in

Figure 2C, CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd nanocomposites were prepared by assembling MWCNTs-AuPtPd on chitosan substrate. CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd nanocomposites were uniformly distributed without agglomeration which had good film forming property and stability. Nanocomposites were further characterized by SEM-EDS mapping. The mappings of elements in

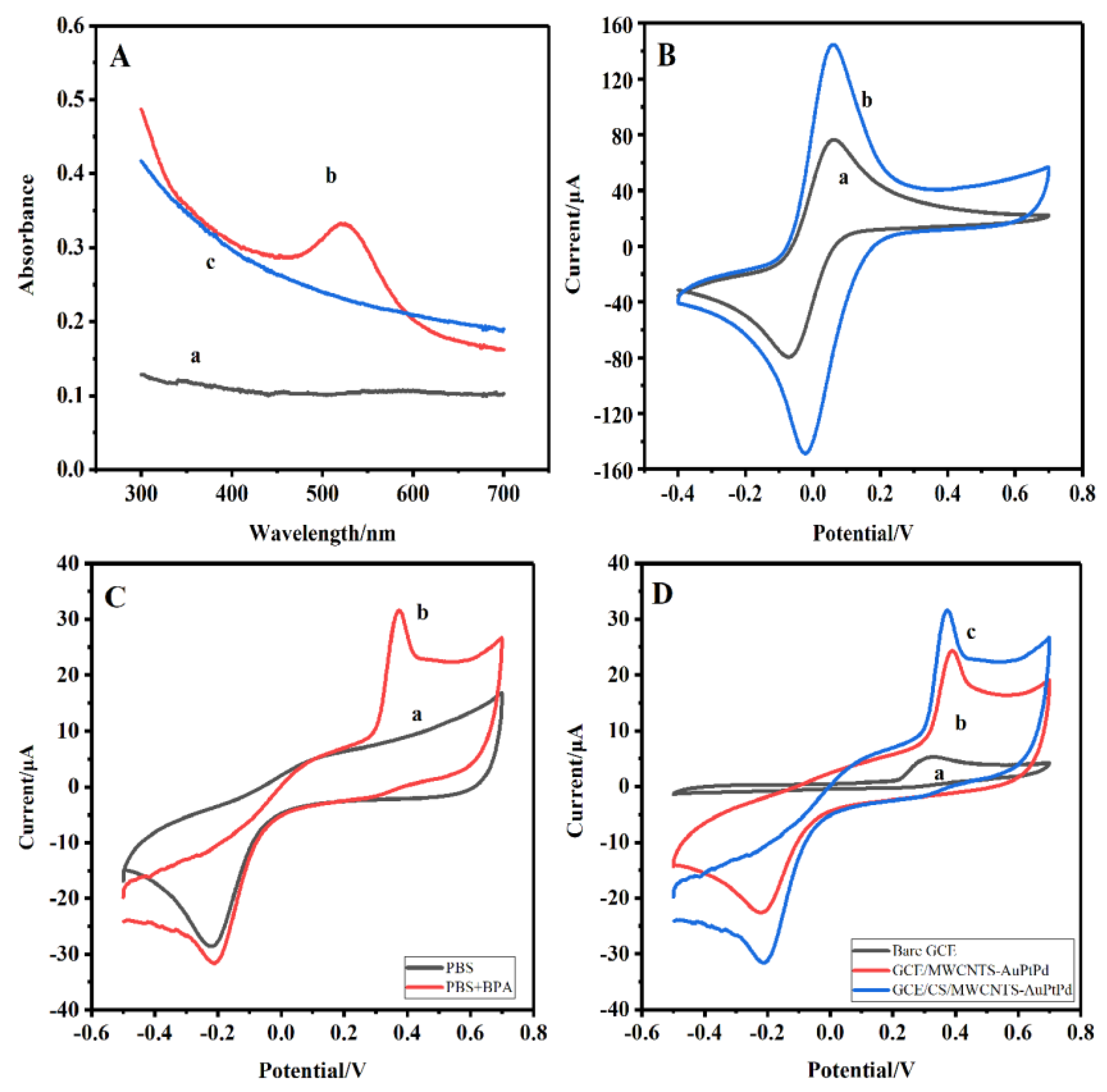

Figure 2E showed Au, Pt and Pd atoms were homogenously distribution on the surface of the MWCNTs, which indicated that Au, Pt and Pd nanoparticles were attached to the surface of MWCNTs successfully. The typical UV-vis spectra of MWCNTs, MWCNT-Au and MWCNTs-AuPtPd were shown in

Figure 3A. The spectra of MWCNTs displayed no adsorption peak (curve a). The adsorption peak at 570 nm belonged to Au for the spectra of MWCNT-Au (curve b), which was agreed with the reported results. The Au absorption peak was invisible for the spectra of MWCNTs-AuPtPd (curve c) owing to the coverage of deposition of Pt and Pd nanoparticle on the MWCNTs-Au, which further indicated AuPtPd were successfully functionalized to the surface of MWCNTs.

CV tests were used to study the property of different modified electrodes in PBS solution containing 0.1M KCl and 5mM [Fe(CN)

6]

3-/4- (

Figure 3B). Compared with bare GCE (curve a), the peak currents were significantly increased at the GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd (curve b). This was probably attributed to the synergistic effect of high electron transfer rate of MWCNTs-AuPtPd and excellent membrane-forming capacity of chitosan. The chitosan played a vital role for the formation of film, and it also enhanced the stability of nanocomposite, which had been reported in previous works [

32]. The results indicated that the CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd nanocomposite had good electrical conductivity and stability.

3.2. Enhancement effect of the nanocomposite for BPA detection

The enhancement effect of CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd nanocomposites for BPA oxidation was tested by CV. CV curves of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd were tested in PBS solution with the absence and existence of 0.1 mM BPA. As shown in

Figure 3C,no anodic peak current was obtained without BPA (curve a). In comparison, the oxidation current was enhanced upon BPA adding (curve b), and the potential of oxidation peak was at 0.37 V which was attributed to the electrooxidation of BPA, indicating a high catalytic activity of CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd for BPA. A comparison of the CV curves at bare GCE, GCE/MWCNTs-AuPtPd, and GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd in 0.1 mM BPA solution were shown in

Figure 3D. Obviously, GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd got a clear oxidation peak with response current of 31.6 μA. Under the same conditions, the oxidation peak of BPA on bare GCE was wider with a peak current of 5.2 μA and the electrochemical signal was low, indicating that the direct electron transfer for BPA was slow at bare GCE. The peak current of GCE/MWCNTs-AuPtPd was higher than bare GCE, and the response current was 23.8 μA, which was also lower than the response current of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd. These results showed the current was increased significantly at GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd, which was about 6.1 times and 1.3 times as high as that of bare GCE and GCE/MWCNTs-AuPtPd. GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd had better oxidation performance for BPA, which may be related to the unique properties of nanocomposites. Firstly, the stability of the sensor could be improved by the good film formation of chitosan. Secondly, AuPtPd trimetallic nanoparticles had good electrical conductivity and catalytic performance, which could catalyze the oxidation of BPA.

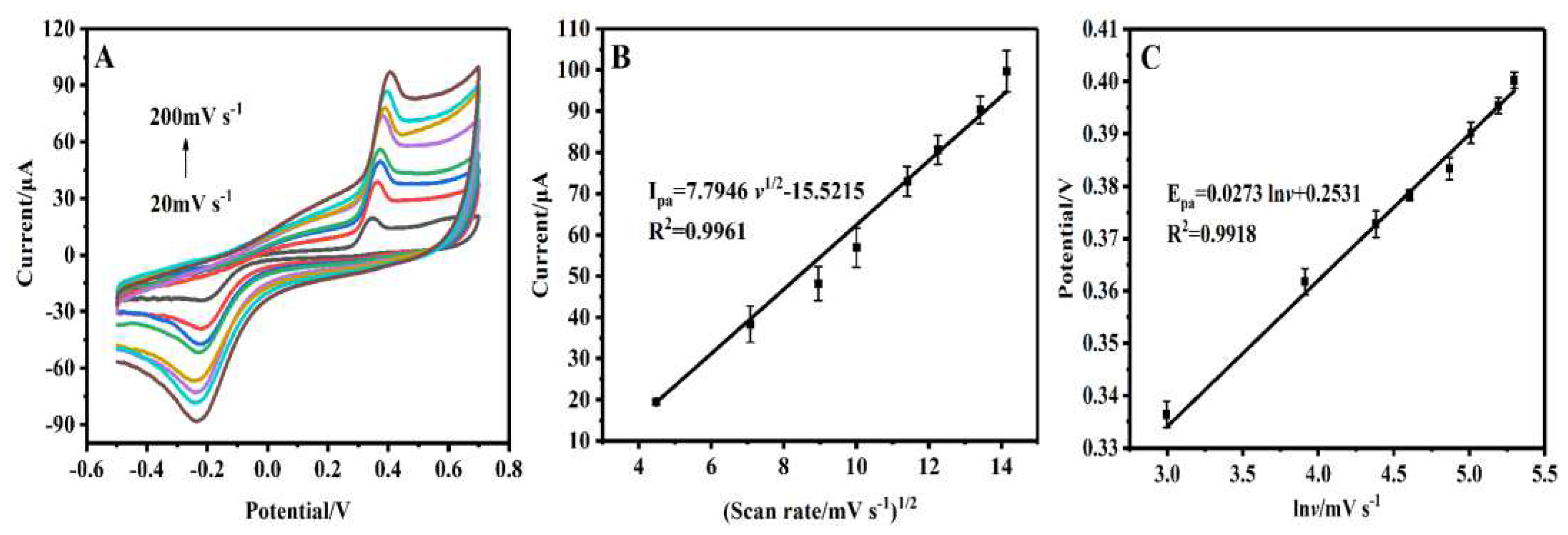

3.3. Kinetic studies of BPA on GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd

CVs were performed for investigating the kinetics of electrocatalytic oxidation of BPA at GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd at different scan rates from 20 to 220 mV s

-1 in 100 μM BPA soltion. The anode current signal increased with the increment of scanning rate (

Figure 4A). As shown in

Figure 4B, the square root of scan rates and the anode current signal (I

pa) for BPA at GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd showed linear correlation, and the linear equation was:

which indicated that the process of BPA oxidation on the GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd was diffusion-controlled [

33]. In addition, the anodic peak potential (Ipa) and the natural logarithm of scan rate (v) had well linear relationship in

Figure 4C, and the equation was:

According to the diffusion-controlled process and irreversible oxidation, the peak potential was defined by the equation:

Where E

θ, R, T, α, n, v, F, k

θ was the standard redox potential, universal gas constant, absolute temperature, transfer coefficient, number of electron transfer involved in rate determining step, scan rate, Faraday constant, standard rate constant of the reaction, respectively. From the linear relationship of Epa and lnv, the slope of the equation was RT/αnF. Generally, for an irreversible oxidation process, the value of α is considered to be 0.5. The value of T, R and F were 298 K, 8.314 J mol

-1 K

-1 and 96480 C mol

-1, respectively. Finally, the value of n was calculated as 2.03, which was expressed the electron transfer for BPA oxidation at GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd included 2 electrons.

3.4. Optimization of conditions for BPA detection

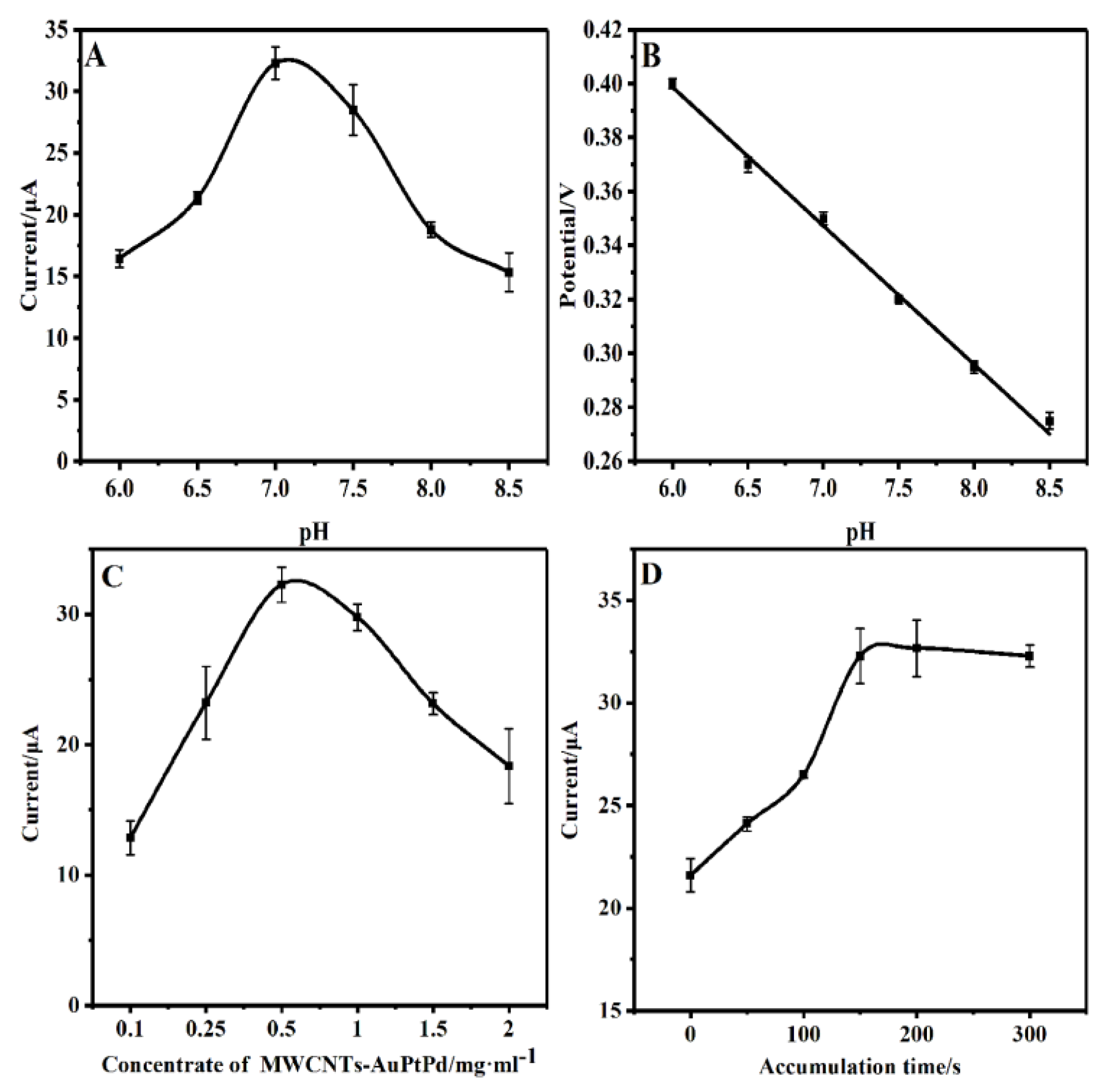

The effect of pH for BPA oxidation was studied to obtain optimum pH for the sensitive determination of BPA by GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd. The DPV curves of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd were recorded in presence of 100 μM BPA at 0.1 M of PBS solution with various pH. As seen in

Figure 5A, the signals of the sensor first increased with the pH changing from 6.0 to 7.0, afterwards the signals of the designed electrode decreased as the pH further increased. In acidic solution, the presence of anions inhibited the phenolic groups of BPA, then the oxidation current of BPA was reduced. On the other hand, oxidation currents dropped because of the decrease of proton concentration in alkaline solution. Hence, pH 7.0 was chosen for determination of BPA. Additionally, the relationship between oxidation peak potentials of BPA and pH were analyzed at GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd. As shown in

Figure 5B, with the increment of pH from 6.0 to 8.5, the peak potentials shifted to more negative potential and showed a linear correlation, and the linear equation was:

According to equation, the value of slope was 51.4 mV pH-1, which was approximately to the theoretical value of 59 mV pH−1. Therefore, this result reflected that the number of electrons and protons were equal in transfer process for the oxidation of BPA on GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd.

The concentrates of MWCNTs-AuPtPd affected the sensitivity of the prepared electrode. DPV was recorded the effect of various concentrations of MWCNTs-AuPtPd to the oxidation current in 100 μM BPA solution. As seen in

Figure 5C, with the concentrate of MWCNTs-AuPtPd increased from 0.1 to 0.5 mg ml

-1, the peak currents increased remarkably and then the currents decreased with the concentrate further increasing. The oxidation current of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd reached the maximum when the concentrates of MWCNTs-AuPtPd was 0.5 mg mL

-1. Therefore, the concentrates of 0.5 mg ml

-1 were selected to prepare GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd.

The effects of accumulation time for electrochemical response of BPA were studied by DPV because the amount of BPA adsorbed on the modified electrode could obviously affect the sensitivity of determination. As shown in

Figure 5D, accumulation time of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd for BPA detection was recorded by DPV from 0 to 300 s. The response current of the modified electrode for BPA increased with the incubation time increasing from 0 to 150 s. Then the current remained stable beyond 150 to 300 s because of the saturated adsorption of BPA on GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd surface. Therefore, the optimal accumulation time of 150 s was selected as the best accumulation time for BPA detection.

3.5. Electrochemical detection of BPA

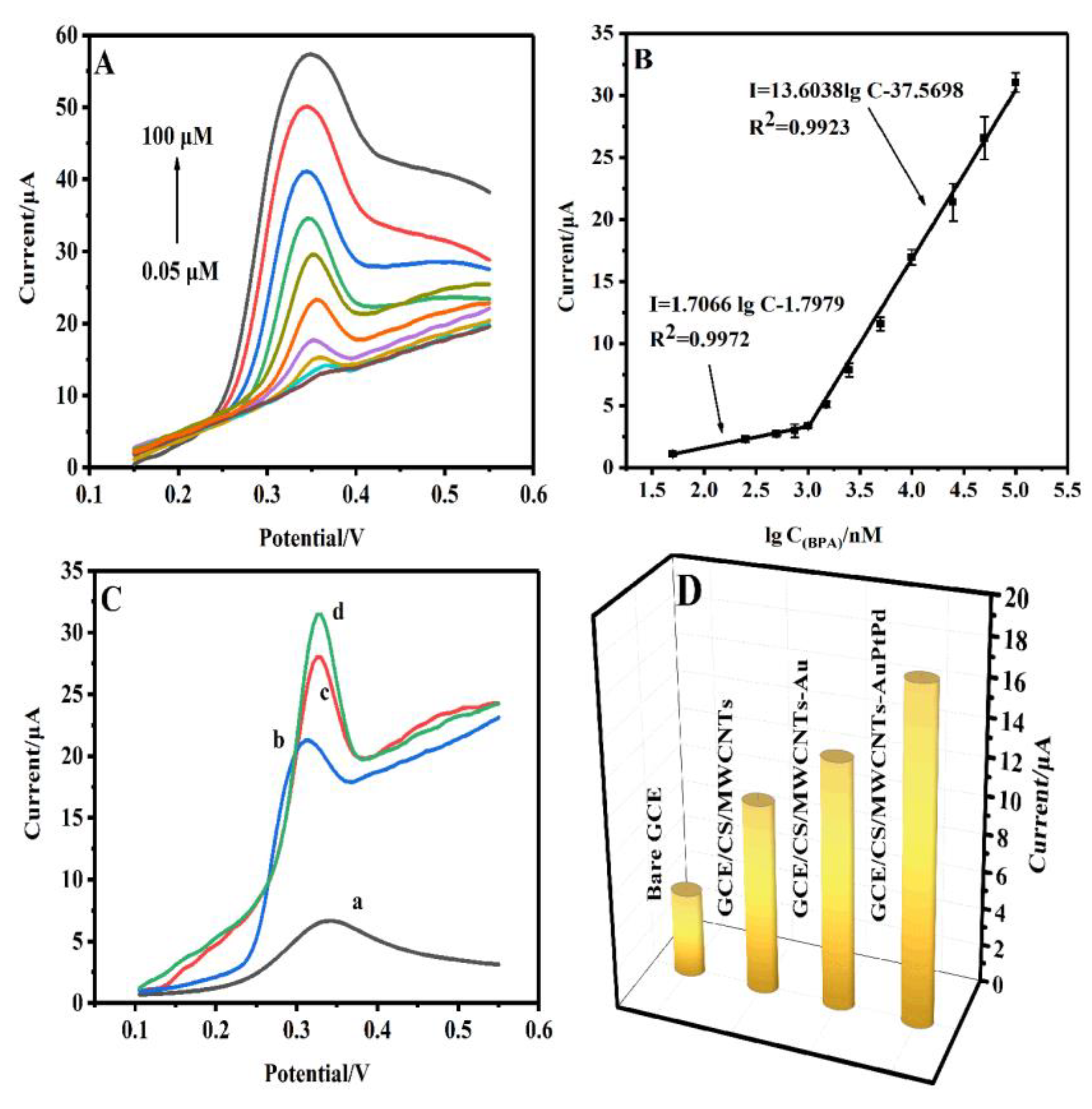

The analytical performance of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd towards BPA was studied. As shown in

Figure 6A, under the optimal conditions, DPV test was used to record the responses current of the GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd for various concentrations of BPA. The responses currents change ed with the changes of BPA concentrations. As shown in

Figure 6B, a linear correlation between the current of the designed sensor and BPA concentration was in the range from 0.05 to 1 µM and 1 to 100 µM, and the linear equations were:

The limit of detection (LOD) was calculated according to the formula LOD = 3σ/k, σ was standard deviation of blank response and k was slope of calibration curve. The limit of detection for BPA was 1.4 nM (S/N=3) at GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd. The designed sensor was compared with the reported sensors for the detection of BPA (

Table 1). As noticed, compared with the PdNPs and polyethyleneimine with graphene oxide aerogel modified electrode [

34], and the electrochemical sensor based on covalent organic framework [

35], the GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd had a wider range and lower detection limit. The detection limit of the sensor in this work was much lower than the dual-signal electrochemical sensor based on nanoporous gold and prepared by Zhang et al. [

36]. Although the detection range of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd was similar with the sensor based on Na-doped WO

3, which was designed by Zhou et al. [

37], and the MnS modified electrode prepared by Annalakshmi et al. [

38], the detection limit of the sensor in this work was lower. Thus, the results showed that the GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd sensor exhibited a wider detection range with a low detection limit, which proved the better property of the designed sensor compared to previously reported sensors owing to the superior catalytic properties of MWCNTs-AuPtPd and the good film formation of chitosan. Several other papers have addressed lower LODs than this study [

39,

40,

41,

42]. However, as far as we know, trimetallic nanoparticles functionalized MWCNTs coupled with chitosan was first reported on the detection of BPA.

DPVs were used for studying the electrocatalytic capacity of different modified electrodes in 10 µM BPA solution. As shown in

Figure 6C and D, the response current was weak at bare GCE (curve a). Compared to bare GCE, the response current was higher and the potential shifted negatively at GCE/CS/MWCNTs (curve b), which could be owing to the good conductivity of MWCNTs. The response current at GCE/CS/MWCNTs-Au (curve c) were higher than GCE/CS/MWCNTs due to the catalytic properties of gold nanoparticles. GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd (curve d) presented the highest peak current because of the synergy effects of MWCNTs-AuPtPd and the peak current of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd (I

pa=17.42) was about 1.63 times as high as that of the GCE/CS/MWCNTs (I

pa=10.71). Generally, electrooxidation current could reflect the catalytic capacity of the electrode. Those results indicated that GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd exhibited the best electrocatalytic capacity compared with other tested electrode.

3.6. Reproducibility, repeatability, stability and selectivity

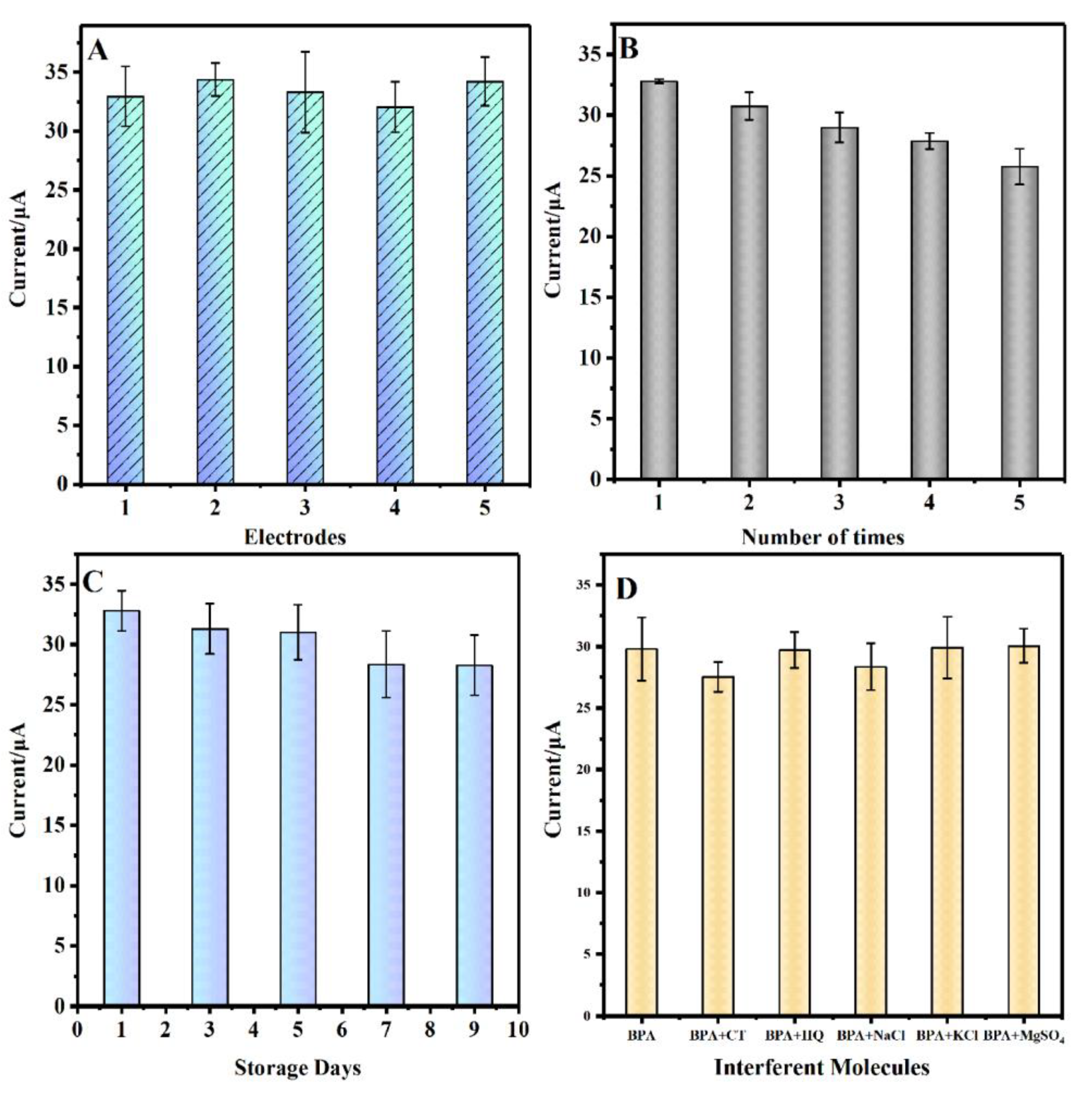

To evaluate the reproducibility of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd, five modified electrodes were prepared with the same way for the detection of 100 µM BPA solution (

Figure 7A). The relative standard deviation (RSD) of the signal was 4.14%, which reflected that there was satisfactory reproducibility of the GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd. In addition, one electrode was chosen to evaluate the repeatability of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd by measuring in the same concentration of BPA for five times (

Figure 7B), and the RSD of response current was 7.03%, indicating that the designed sensor possessed well repeatability for BPA detection. The stability of the designed sensor, was researched by recording the oxidation current of 0.1 mM BPA solution for 9 days (

Figure 7C), the current response of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd reserved 87.67% of the original response current. The result verified that the designed sensor possessed a favorable stability.

Selectivity was a vital parameter for electrochemical sensor. DPV response of several common interfering species was measured in the presence of BPA for the sensor. As shown in

Figure 7D, there was little influence on the current response of 0.1 M BPA by adding 100-fold higher concentrations of ions (Mg

2+, Na

2+, K

+ and SO

42-), and adding 10-fold higher concentrations of BPA analogs (HQ and CT). The results indicated the electrochemical sensor had excellent anti-interference ability and good selectivity for BPA determination. However, the designed sensor could not distinguish other bisphenol compounds (such as bisphenol E, bisphenol M and bisphenol Z).

3.7. Real sample analysis

In order to study the feasibility of GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd, the prepared electrode was used to analyze BPA in real samples. Tap water, orange juice, and milk were used as the actual samples in the recovery test. Recovery tests were using standard addition method to validate potential practical application of the designed eletrochemical sensor. As seen in

Table 2, the designed sensor showed an excellent recovery from 94.4% to 103.6%, and the RSD ranged from 1.7% to 6.2%, which demonstrated the designed eletrochemical sensor had high accuracy and could be applied for the detection of food samples.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a novel method based on the CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd nanocomposites modified electrode for BPA detection in food has been developed. AuPtPd trimetallic nanoparticles are first assembled on MWCNTs using in-situ growth method. Then MWCNTs-AuPtPd is further assembled on chitosan substrate to prepared CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd nanocomposites which show excellent electrical conductivity and catalytic performance for BPA oxidation. The CV and DPV studies demonstrate that GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd has sensitive electrochemical response towards BPA electrooxidation due to superior catalytic properties of MWCNTs-AuPtPd, good membrane-forming capacity of chitosan, and the synergistic effect of CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd nanocomposites. The modified electrode reveals a wide concentration range from 0.05 to 100 µM, and the low LOD is 1.4 nM. The GCE/CS/MWCNTs-AuPtPd also possesses satisfactory performance such as well anti-interferential ability and good repeatability. The designed sensor is also applied to detect the BPA in food samples, which demonstrates that the designed senor is responsible and can be used as an available tool for sensitive and convenient determination for actual applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.H., Y.L. and J.C.; methodology, Y.G. and J.C.; investigation, Y.P., Y.L. and Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.P.; writing—review and editing, E.H. and L.L.; supervision, Y.L. and L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21205050), China Agriculture Research System (CARS-27-01A), and Science and Technology Plan of Jiangsu Market Supervision and Administration Bureau (No. KJ21125100).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21205050), China Agriculture Research System (CARS-27-01A), and Science and Technology Plan of Jiangsu Market Supervision and Administration Bureau (No. KJ21125100).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financialinterests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Kim, J.I.; Lee, Y.A.; Shin, C.H.; Hong, Y.C.; Kim, B.N.; Lim, Y.H. Association of bisphenol A, bisphenol F, and bisphenol S with ADHD symptoms in children. Environ. Int. 2022, 161, 107093–107103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Han, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhen, H.; Wu, C.; Yu, Q.; Xiu, G. B, N-decorated carbocatalyst based on Fe-MOF/BN as an efficient peroxymonosulfate activator for bisphenol A degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 430, 127832–127847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, R.; Shi, W.; Zhou, X.; Sun, S. The association between bisphenol A exposure and oxidative damage in rats/mice: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 292, 118444–118453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.; Adegoke, E.; Pang, M.G. Drivers of owning more BPA. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 126076–126092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, P.; Zhong, H.N.; Qiu, K.; Li, D.; Wu, G.; Sui, H.X.; Song, Y. Exposure to bisphenol A and its substitutes, bisphenol F and bisphenol S from canned foods and beverages on Chinese market. Food Control 2021, 120, 107502–107510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durovcova, I.; Kyzek, S.; Fabova, J.; Makukova, J.; Galova, E.; Sevcovicova, A. Genotoxic potential of bisphenol A: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 306, 119346–119362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, X. Hazards of bisphenol A (BPA) exposure: A systematic review of plant toxicology studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121488–121501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gely, C.A.; Huesca, A.; Picard-Hagen, N.; Toutain, P.L.; Berrebi, A.; Gauderat, G.; Gayrard, V.; Lacroix, M.Z. A new LC/MS method for specific determination of human systemic exposure to bisphenol A, F and S through their metabolites: Application to cord blood samples. Environ. Int. 2021; 151, 106429–106438. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33636497.

- Fernandez, M.A.M.; Andre, L.C.; Cardeal, Z.L. Hollow fiber liquid-phase microextraction-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry method to analyze bisphenol A and other plasticizer metabolites. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1481, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wang, J.; Yue, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J. Simultaneous colorimetric determination of bisphenol A and bisphenol S via a multi-level DNA circuit mediated by aptamers and gold nanoparticles. Microchim Acta. 2017, 184, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Chen, S.; Shi, T.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Competitive plasmonic biomimetic enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for sensitive detection of bisphenol A. Food Chem. 2021, 344, 128602–128610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, X.; Feng, D.Q.; Zhao, J.; Fan, D.; Wang, W. In-situ hydrothermal synthesis of molecularly imprinted polymers coated carbon dots for fluorescent detection of bisphenol A. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 228, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xu, S. Visualizing BPA by molecularly imprinted ratiometric fluorescence sensor based on dual emission nanoparticles. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 92, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavipanah, I.; Rounaghi, G.H.; Deiminiat, B.; Damirchi, S.; Abnous, K.; Izadyar, M.; Khavani, M. A new electrochemical aptasensor based on MWCNT-SiO2@Au core-shell nanocomposite for ultrasensitive detection of bisphenol A. Microchem. J. 2019, 146, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Gao, J.; Lu, X.; Huang, C.; Dhanjai; Chen, J. Graphdiyne: A new promising member of 2D all-carbon nanomaterial as robust electrochemical enzyme biosensor platform. Carbon 2020, 156, 568–575. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S. N-doped MoS2-nanoflowers as peroxidase-like nanozymes for total antioxidant capacity assay. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1180, 338740–338752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, N.; Salimi, A.; Sham, T.K.; Bazylewski, P.; Fanchini, G.; Fathi, F.; Soleimani, F. Hierarchical Co(OH)2/FeOOH/WO3 ternary nanoflowers as a dual-function enzyme with pH-switchable peroxidase and catalase mimic activities for cancer cell detection and enhanced photodynamic therapy. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 129134–129146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Niu, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Zeng, L.; Liu, A. Hierarchical porous MoS2 particles: excellent multi-enzyme-like activities, mechanism and its sensitive phenol sensing based on inhibition of sulfite oxidase mimics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 425, 128053–128062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, N.; Chen, S.; Tian, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Lu, X. Cu2+-doped polypyrrole nanotubes with promoted efficiency for peroxidase mimicking and electrochemical biosensing. Mater. Today Chem. 2020, 18, 100374–100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Wu, X.; Dong, Y.; Wang, G.L. Smart nanozyme of silver hexacyanoferrate with versatile bio-regulated activities for probing different targets. Talanta 2021, 228, 122268–122277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leau, S.A.; Lete, C.; Lupu, S. Nanocomposite Materials based on Metal Nanoparticles for the Electrochemical Sensing of Neurotransmitters. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Sahoo, S.; Mohapatra, D.; Ahmad, M.; Iqbal, S.; Javed, M.S.; Gu, S.; Qin, N.; Lamiel, C.; Zhang, K. Recent progress in trimetallic/ternary-metal oxides nanostructures: Misinterpretation/misconception of electrochemical data and devices. Appl. Mater. Today 2022, 26, 101297–101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Ma, L.; Chen, Y.; Fu, L.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, C.; Liu, Q. Metal-organic framework derived hollow rod-like NiCoMn ternary metal sulfide for high-performance asymmetric supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 131003–131013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wu, D.; Tu, S.; Yang, C.; Chen, D.; Xu, Y. CRISPR/Cas9 cleavage triggered ESDR for circulating tumor DNA detection based on a 3D graphene/AuPtPd nanoflower biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 173, 112821–112828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.X.; Zhou, Y.T.; Zhu, Y.F.; Chen, Z.Y.; Yan, J.M.; Jiang, Q. Tri-metallic AuPdIr nanoalloy towards efficient hydrogen generation from formic acid. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2022, 309, 121228–121236. [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Chen, F.; Yu, H. Mass-transfer control for selective deposition of well-dispersed AuPd cocatalysts to boost photocatalytic H2O2 production of BiVO4. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 443, 136429–136438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.C.; Hossain, M.F.; Yoon, H.; Park, J.Y. Trimetallic Pd@Au@Pt nanocomposites platform on -COOH terminated reduced graphene oxide for highly sensitive CEA and PSA biomarkers detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 100, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cen, S.Y.; Ge, X.Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, A.J.; Feng, J.J. Label-free electrochemical immunosensor for ultrasensitive determination of cardiac troponin I based on porous fluffy-like AuPtPd trimetallic alloyed nanodendrites. Microchem. J. 2021, 169, 106568–106577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, J.; Xue, G.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, P. Activation of peracetic acid by RuO2/MWCNTs to degrade sulfamethoxazole at neutral condition. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 134217–134227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouaoui, F.; Bourouina-Bacha, S.; Bourouina, M.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; Zine, N.; Errachid, A. Electrochemical sensors based on molecularly imprinted chitosan: A review. TrAC-Trend Anal. Chem. 2020, 130, 115982–115998. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cheng, W.; Wu, D.; Yang, Y.; Feng, X.; Gao, C.; Meng, L.; Shen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X. An electrochemical method for determination of amaranth in drinks using functionalized graphene oxide/chitosan/ionic liquid nanocomposite supported nanoporous gold. Food Chem. 2022, 367, 130727–130735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.D.; Doan, T.C.D.; Huynh, T.M.; Nguyen, V.N.P.; Dinh, H.H.; Dang, D.M.T.; Dang, C.M. An electrochemical sensor based on polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan-thermally reduced graphene composite modified glassy carbon electrode for sensitive voltammetric detection of lead. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 345, 130443–130452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.Y.; Alam, A.U.; Howlader, M.M.R. Fabrication of highly sensitive Bisphenol A electrochemical sensor amplified with chemically modified multiwall carbon nanotubes and β-cyclodextrin. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 320, 128319–128328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.Y.; Park, H.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, D.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Myung, N.V.; Lee, K.H. Hierarchically palladium nanoparticles embedded polyethyleneimine-reduced graphene oxide aerogel (RGA-PEI-Pd) porous electrodes for electrochemical detection of bisphenol a and H2O2. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 134250–134262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.H.; Huang, Y.Y.; Wang, L.; Shen, X.F.; Wang, Y.Y. Determination of bisphenol A and bisphenol S by a covalent organic framework electrochemical sensor. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114616–114625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, X.; Sun, S.; Li, Y. A novel dual-signal electrochemical sensor for bisphenol A determination by coupling nanoporous gold leaf and self-assembled cyclodextrin. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 271, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, S.; Dang, Y. A novel electrochemical sensor for highly sensitive detection of bisphenol A based on the hydrothermal synthesized Na-doped WO3 nanorods. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 245, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annalakshmi, M.; Balamurugan, T.S.T.; Kumaravel, S.; Chen, S.M.; He, J.L. Facile Hydrothermal Synthesis of Manganese Sulfide Nanoelectrocatalyst for Highly Sensitive Detection of Bisphenol A in Food and Eco-samples. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133316–133325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, T.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, Min. ; Zhang, Z.; Lai, W.;Kadasala, N.R.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y. Magnetic-Core–Shell–Satellite Fe3O4-Au@Ag@(Au@Ag) nanocomposites fordetermination of trace bisphenol A based on Surface-Enhanced Resonance Raman Scattering (SERRS). Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3322–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Ahmed, J.; Asiri, A.M.; Alfaifi, S.Y. Ultra-sensitive, selective and rapid carcinogenic bisphenol A contaminant determination using low-dimensional facile binary Mg-SnO2 doped microcube by potential electro-analytical technique for the safety of environment. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 109, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Ruan, X.; Shao, J.; Shan, J.; Shan, X.; Ye, H.; Shi, Y. Facile preparation of aluminum nanocomposites and the utilization in analyzing BPA in urine samples. Chem. Pap. 2022, 76, 2029–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, S.; Shi, P.; Zhao, G. A Highly Sensitive and Selective Label-free Electrochemical Biosensor with a Wide Range of Applications for Bisphenol A Detection. Electroanal. 2022, 34, 743 –751. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).