Submitted:

25 April 2023

Posted:

26 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Ageing

Ageing and Telomere Length

Diseases and Oral Health

Multimorbidity and Polypharmacy

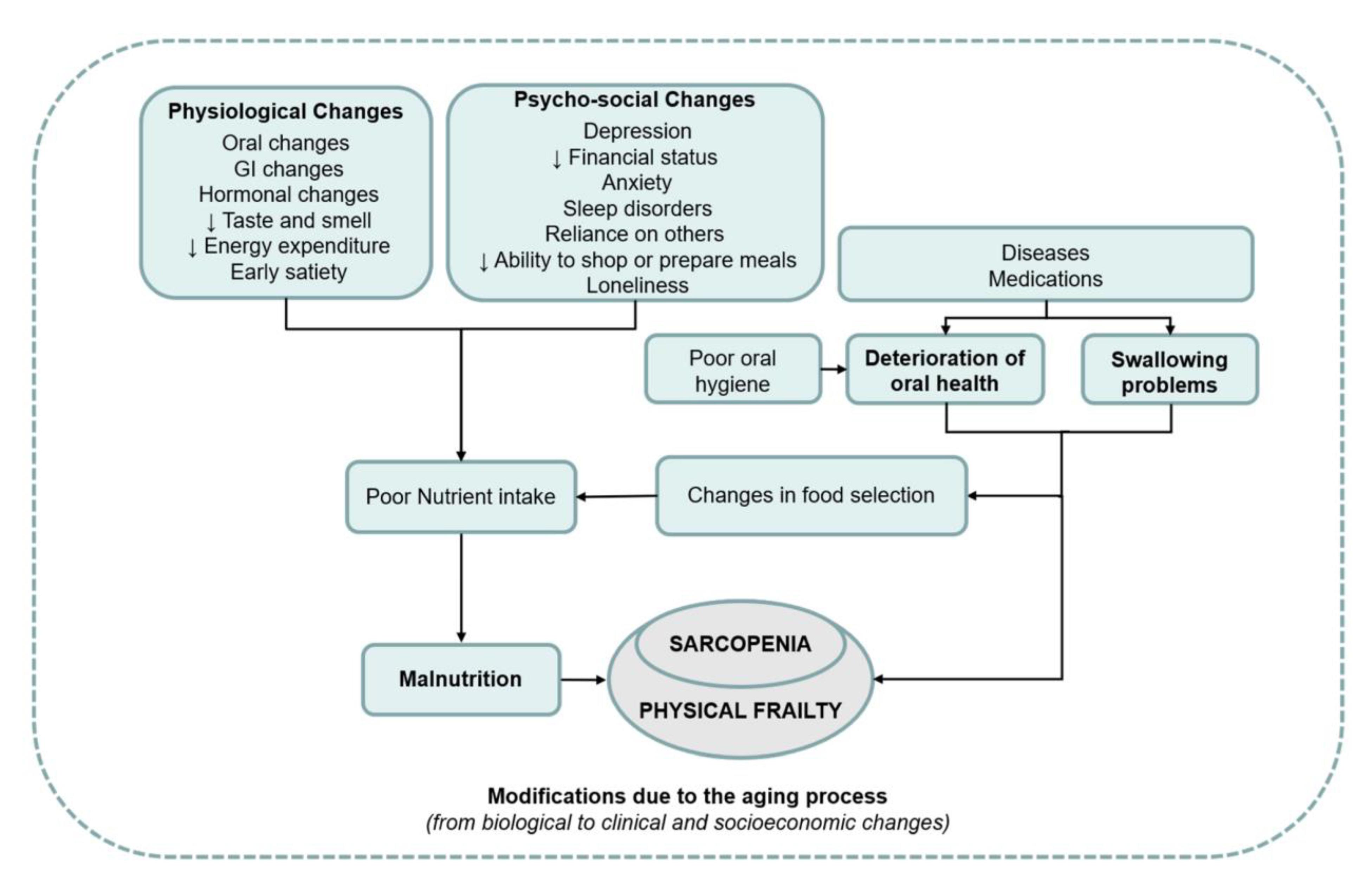

Frailty and Oral Health

Sarcopenia and Oral Health

Disability and Oral Health

Impact of Ageing and Age-Related Diseases on General Healthcare Provision

Impact of Multimorbidity and Polypharmacy on Oral Healthcare Provision

Impact of Frailty, Disability, and Care Dependency on Oral Healthcare Provision

Epilogue

References

- van der Putten GJ, De Visschere L, Maarel-Wiering van der C, Vanobbergen J, Schols J: The importance of oral health in (frail) elderly people - a review. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2013, 4, 339–344. [CrossRef]

- Kossioni AE, Maggi S, Muller F, Petrovic M: Oral health in older people: Time for action. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2018, 9, 3–4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marengoni A, von Strauss E, Rizzuto D, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L: The impact of chronic multimorbidity and disability on functional decline and survival in elderly persons. A community-based, longitudinal study. J. Intern. Med. 2009, 265, 288–295.

- van der Putten GJ, de Baat C, De Visschere L, Schols J: Poor oral health, a potential new geriatric syndrome. Gerodontology 2014, 31 Suppl 1, 17–24. [CrossRef]

- Strehler BL: Understanding aging. Methods Mol. Med. 2000, 38, 1–19.

- Michaud M, Balardy L, Moulis G, Gaudin C, Peyrot C, Vellas B, Cesari M, Nourhashemi F: Proinflammatory cytokines, aging, and age-related diseases. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 877–882. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller RA: The aging immune system: Primer and prospectus. Science 1996, 273, 70–74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansoni P, Vescovini R, Fagnoni F, Biasini C, Zanni F, Zanlari L, Telera A, Lucchini G, Passeri G, Monti D et al: The immune system in extreme longevity. Exp. Gerontol. 2008, 43, 61–65. [CrossRef]

- Sadighi Akha AA: Aging and the immune system: An overview. J. Immunol. Methods 2018, 463, 21–26. [CrossRef]

- Sanders JL, Newman AB: Telomere length in epidemiology: A biomarker of aging, age-related disease, both, or neither? Epidemiol. Rev. 2013, 35, 112–131. [CrossRef]

- Lu W, Zhang Y, Liu D, Songyang Z, Wan M: Telomeres-structure, function, and regulation. Exp. Cell Res. 2013, 319, 133–141. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Rane G, Dai X, Shanmugam MK, Arfuso F, Samy RP, Lai MK, Kappei D, Kumar AP, Sethi G: Ageing and the telomere connection: An intimate relationship with inflammation. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 25, 55–69. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masi S, Gkranias N, Li K, Salpea KD, Parkar M, Orlandi M, Suvan JE, Eng HL, Taddei S, Patel K et al: Association between short leukocyte telomere length, endotoxemia, and severe periodontitis in people with diabetes: A cross-sectional survey. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1140–1147. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masi S, Salpea KD, Li K, Parkar M, Nibali L, Donos N, Patel K, Taddei S, Deanfield JE, D'Aiuto F et al: Oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and telomere length in patients with periodontitis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 50, 730–735. [CrossRef]

- Sanders AE, Divaris K, Naorungroj S, Heiss G, Risques RA: Telomere length attrition and chronic periodontitis: An ARIC Study nested case-control study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, 12–20. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi K, Nishida H, Takeda H, Shin K: Telomere length in leukocytes and cultured gingival fibroblasts from patients with aggressive periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2004, 75, 84–90. [CrossRef]

- Song W, Yang J, Niu Z: Association of periodontitis with leukocyte telomere length in US adults: A cross-sectional analysis of NHANES 1999 to 2002. J Periodontol 2021, 92, 833–843. [CrossRef]

- Botelho J, Mascarenhas P, Viana J, Proenca L, Orlandi M, Leira Y, Chambrone L, Mendes JJ, Machado V: An umbrella review of the evidence linking oral health and systemic noncommunicable diseases. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7614. [CrossRef]

- Gurenlian JR: Inflammation: The relationship between oral health and systemic disease. Dent. Assist. 2009, 78, 8–10, 12-14, 38-40; quiz 41-13.

- Peric M, Marhl U, Gennai S, Marruganti C, Graziani F: Treatment of gingivitis is associated with reduction of systemic inflammation and improvement of oral health-related quality of life: A randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2022, 49, 899–910. [CrossRef]

- Bui FQ, Almeida-da-Silva CLC, Huynh B, Trinh A, Liu J, Woodward J, Asadi H, Ojcius DM: Association between periodontal pathogens and systemic disease. Biomed. J. 2019, 42, 27–35. [CrossRef]

- de Vries SAG, Tan CXW, Bouma G, Forouzanfar T, Brand HS, de Boer NK: Salivary Function and Oral Health Problems in Crohn's Disease Patients. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 1361–1367. [CrossRef]

- Rikardsson S, Jonsson J, Hultin M, Gustafsson A, Johannsen A: Perceived oral health in patients with Crohn's disease. Oral. Health Prev. Dent. 2009, 7, 277–282.

- Ali S, Nagieb CS, Fayed HL: Effect of Behcet's disease-associated oral ulcers on oral health related quality of life. Spec. Care Dentist 2022.

- Mumcu G, Ergun T, Inanc N, Fresko I, Atalay T, Hayran O, Direskeneli H: Oral health is impaired in Behcet's disease and is associated with disease severity. Rheumatology 2004, 43, 1028–1033. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senusi A, Higgins S, Fortune F: The influence of oral health and psycho-social well-being on clinical outcomes in Behcet's disease. Rheumatol. Int. 2018, 38, 1873–1883. [CrossRef]

- Albilia JB, Lam DK, Blanas N, Clokie CM, Sandor GK: Small mouths. .. Big problems? A review of scleroderma and its oral health implications. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 73, 831–836.

- Beaty KL, Gurenlian JR, Rogo EJ: Oral Health Experiences of the Limited Scleroderma Patient. J. Dent. Hyg. 2021, 95, 59–69.

- Chung M, York BR, Michaud DS: Oral Health and Cancer. Curr. Oral. Health Rep. 2019, 6, 130–137. [CrossRef]

- Jobbins J, Bagg J, Finlay IG, Addy M, Newcombe RG: Oral and dental disease in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ 1992, 304, 1612. [CrossRef]

- Vermaire JA, Partoredjo ASK, de Groot RJ, Brand HS, Speksnijder CM: Mastication in health-related quality of life in patients treated for oral cancer: A systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2022, 31, e13744.

- Zhang J, Bellocco R, Sandborgh-Englund G, Yu J, Sallberg Chen M, Ye W: Poor Oral Health and Esophageal Cancer Risk: A Nationwide Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2022, 31, 1418–1425. [CrossRef]

- Auffret M, Meuric V, Boyer E, Bonnaure-Mallet M, Verin M: Oral Health Disorders in Parkinson's Disease: More than Meets the Eye. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2021, 11, 1507–1535. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Baat C, van Stiphout MAE, Lobbezoo F: [The objective oral health of Parkinson's disease patients]. Ned. Tijdschr. Tandheelkd. 2020, 127, 318–322. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama Y, Washio M, Mori M: Oral health conditions in patients with Parkinson's disease. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 14, 143–150. [CrossRef]

- Persson M, Osterberg T, Granerus AK, Karlsson S: Influence of Parkinson's disease on oral health. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1992, 50, 37–42. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro GR, Campos CH, Garcia RC: Oral Health in Elders with Parkinson's Disease. Braz. Dent. J. 2016, 27, 340–344. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saft C, Andrich JE, Muller T, Becker J, Jackowski J: Oral and dental health in Huntington's disease - an observational study. BMC Neurol. 2013, 13, 114.

- Manchery N, Henry JD, Nangle MR: A systematic review of oral health in people with multiple sclerosis. Community Dent. Oral. Epidemiol. 2020, 48, 89–100. [CrossRef]

- Hamza SA, Asif S, Bokhari SAH: Oral health of individuals with dementia and Alzheimer's disease: A review. J. Indian. Soc. Periodontol. 2021, 25, 96–101. [CrossRef]

- Ahola K, Saarinen A, Kuuliala A, Leirisalo-Repo M, Murtomaa H, Meurman JH: Impact of rheumatic diseases on oral health and quality of life. Oral. Dis. 2015, 21, 342–348. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho CG, Medeiros-Filho JB, Ferreira MC: Guide for health professionals addressing oral care for individuals in oncological treatment based on scientific evidence. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 2651–2661. [CrossRef]

- Aleksandric S: Poor oral health: Cause or risk factor for future cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 352, 150–151. [CrossRef]

- Gianos E, Jackson EA, Tejpal A, Aspry K, O'Keefe J, Aggarwal M, Jain A, Itchhaporia D, Williams K, Batts T et al: Oral health and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: A review. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 7, 100179. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurman JH, Bascones-Martinez A: Oral Infections and Systemic Health - More than Just Links to Cardiovascular Diseases. Oral. Health Prev. Dent. 2021, 19, 441–448.

- Venkatasalu MR, Murang ZR, Ramasamy DTR, Dhaliwal JS: Oral health problems among palliative and terminally ill patients: An integrated systematic review. BMC Oral. Health 2020, 20, 79.

- Le Reste JY, Nabbe P, Manceau B, Lygidakis C, Doerr C, Lingner H, Czachowski S, Munoz M, Argyriadou S, Claveria A et al: The European General Practice Research Network presents a comprehensive definition of multimorbidity in family medicine and long term care, following a systematic review of relevant literature. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 319–325.

- Loya AM, Gonzalez-Stuart A, Rivera JO: Prevalence of polypharmacy, polyherbacy, nutritional supplement use and potential product interactions among older adults living on the United States-Mexico border: A descriptive, questionnaire-based study. Drugs Aging 2009, 26, 423–436. [CrossRef]

- Le Reste JY, Nabbe P, Lazic D, Assenova R, Lingner H, Czachowski S, Argyriadou S, Sowinska A, Lygidakis C, Doerr C et al: How do general practitioners recognize the definition of multimorbidity? A European qualitative study. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 22, 159–168.

- Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE: What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 230.

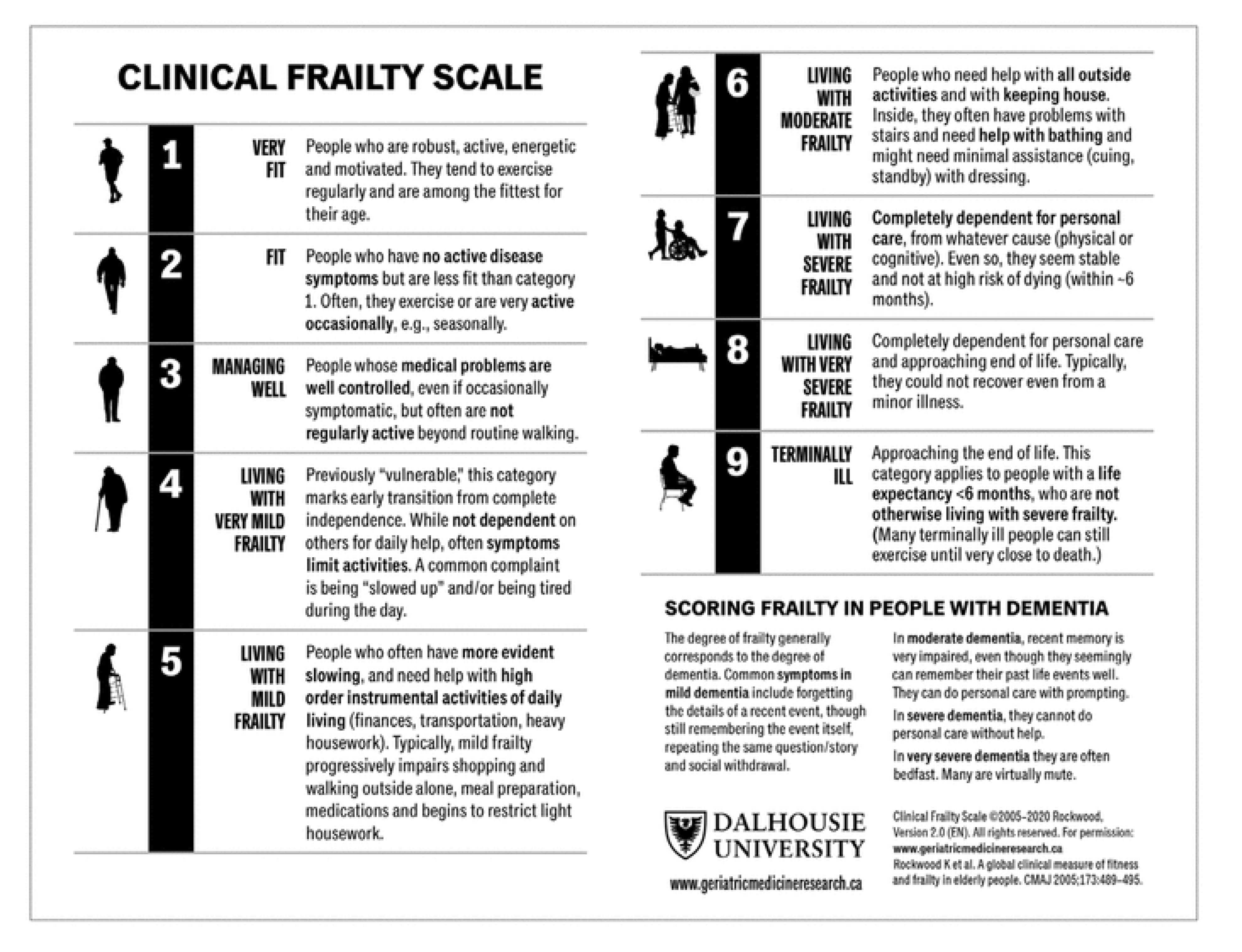

- Rockwood K, Mitnitski A: Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007, 62, 722–727. [CrossRef]

- Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A: A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005, 173, 489–495. [CrossRef]

- Collard RM, Boter H, Schoevers RA, Oude Voshaar RC: Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: A systematic review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 1487–1492. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamdem B, Seematter-Bagnoud L, Botrugno F, Santos-Eggimann B: Relationship between oral health and Fried's frailty criteria in community-dwelling older persons. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 174.

- de Andrade FB, Lebrao ML, Santos JL, Duarte YA: Relationship between oral health and frailty in community-dwelling elderly individuals in Brazil. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 809–814. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira LF, Scariot EL, da Rosa LHT: The effect of different exercise programs on sarcopenia criteria in older people: A systematic review of systematic reviews with meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2023, 105, 104868. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao H, Cheng R, Song G, Teng J, Shen S, Fu X, Yan Y, Liu C: The Effect of Resistance Training on the Rehabilitation of Elderly Patients with Sarcopenia: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19(23).

- Yoo JI, Ha YC, Cha Y: Nutrition and Exercise Treatment of Sarcopenia in Hip Fracture Patients: Systematic Review. J. Bone Metab. 2022, 29, 63–73. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatta K, Ikebe K: Association between oral health and sarcopenia: A literature review. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2021, 65, 131–136. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzolino D, Passarelli PC, De Angelis P, Piccirillo GB, D'Addona A, Cesari M: Poor Oral Health as a Determinant of Malnutrition and Sarcopenia. Nutrients 2019, 11(12).

- Holm-Pedersen P, Schultz-Larsen K, Christiansen N, Avlund K: Tooth loss and subsequent disability and mortality in old age. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 429–435. [CrossRef]

- Komiyama T, Ohi T, Miyoshi Y, Murakami T, Tsuboi A, Tomata Y, Tsuji I, Watanabe M, Hattori Y: Association Between Tooth Loss, Receipt of Dental Care, and Functional Disability in an Elderly Japanese Population: The Tsurugaya Project. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, 2495–2502. [CrossRef]

- Komiyama T, Ohi T, Tomata Y, Tanji F, Tsuji I, Watanabe M, Hattori Y: Dental Status is Associated With Incident Functional Disability in Community-Dwelling Older Japanese: A Prospective Cohort Study Using Propensity Score Matching. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 30, 84–90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuyama Y, Listl S, Jurges H, Watt RG, Aida J, Tsakos G: Causal Effect of Tooth Loss on Functional Capacity in Older Adults in England: A Natural Experiment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 1319–1327. [CrossRef]

- Yin Z, Yang J, Huang C, Sun H, Wu Y: Eating and communication difficulties as mediators of the relationship between tooth loss and functional disability in middle-aged and older adults. J. Dent. 2020, 96, 103331. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotronia E, Brown H, Papacosta O, Lennon LT, Weyant RJ, Whincup PH, Wannamethee SG, Ramsay SE: Oral health problems and risk of incident disability in two studies of older adults in the United Kingdom and the United States. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 2080–2092. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization WH: World report on Disability.. In.; 2011.

- Motl RW, McAuley E: Physical activity, disability, and quality of life in older adults. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 21, 299–308. [CrossRef]

- Clouston SA, Brewster P, Kuh D, Richards M, Cooper R, Hardy R, Rubin MS, Hofer SM: The dynamic relationship between physical function and cognition in longitudinal aging cohorts. Epidemiol. Rev. 2013, 35, 33–50. [CrossRef]

- Bossers WJ, van der Woude LH, Boersma F, Scherder EJ, van Heuvelen MJ: Recommended measures for the assessment of cognitive and physical performance in older patients with dementia: A systematic review. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Dis. Extra 2012, 2, 589–609. [CrossRef]

- Gill TM: Assessment of function and disability in longitudinal studies. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S308-312.

- Mann WC, Ottenbacher KJ, Fraas L, Tomita M, Granger CV: Effectiveness of assistive technology and environmental interventions in maintaining independence and reducing home care costs for the frail elderly. A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Fam. Med. 1999, 8, 210–217.

- Parsons J, Rouse P, Robinson EM, Sheridan N, Connolly MJ: Goal setting as a feature of homecare services for older people: Does it make a difference? Age Ageing 2012, 41, 24–29. [CrossRef]

- Ryburn B, Wells Y, Foreman P: Enabling independence: Restorative approaches to home care provision for frail older adults. Health Soc. Care Community 2009, 17, 225–234. [CrossRef]

- Evans D: Exploring the concept of respite. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 1905–1915. [CrossRef]

- Shaw C, McNamara R, Abrams K, Cannings-John R, Hood K, Longo M, Myles S, O'Mahony S, Roe B, Williams K: Systematic review of respite care in the frail elderly. Health Technol. Assess. 2009, 13, 1–224, iii.

- Hogan L, Boron JB, Masters J, MacArthur K, Manley N: Characteristics of dementia family caregivers who use paid professional in-home respite care. Home Health Care Serv. Q. 2022, 41, 310–329. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker SG, Hawley MS: Telecare for an ageing population? Age Ageing 2013, 42, 424–425. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan TA: Professional education to meet the oral health needs of older adults and persons with disabilities. Spec. Care Dentist 2013, 33, 190–197. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsonello A, Pedone C, Incalzi RA: Age-related pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes and related risk of adverse drug reactions. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 571–584. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu B, Dion MR, Jurasic MM, Gibson G, Jones JA: Xerostomia and salivary hypofunction in vulnerable elders: Prevalence and etiology. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. 2012, 114, 52–60. [CrossRef]

- Ship JA, Pillemer SR, Baum BJ: Xerostomia and the geriatric patient. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 50, 535–543. [CrossRef]

- van der Putten GJ, Brand HS, Schols JM, de Baat C: The diagnostic suitability of a xerostomia questionnaire and the association between xerostomia, hyposalivation and medication use in a group of nursing home residents. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2011, 15, 185–192. [CrossRef]

- Thomson WM, van der Putten GJ, de Baat C, Ikebe K, Matsuda K, Enoki K, Hopcraft MS, Ling GY: Shortening the xerostomia inventory. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. Endod. 2011, 112, 322–327. [CrossRef]

- Griffin SO, Jones JA, Brunson D, Griffin PM, Bailey WD: Burden of oral disease among older adults and implications for public health priorities. Am. J. Public. Health 2012, 102, 411–418. [CrossRef]

| Never | Ocasionally | Often | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | My mouth feels dry when eating a meal | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 2 | My mouth feels dry | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 3 | I have difficulty in eating dry foods | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 4 | I Have difficulties swallowing certain foods | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 5 | My lips feel dry | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).