Submitted:

25 April 2023

Posted:

26 April 2023

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Person-centered, led by individuals’ needs rather than technologies or other external drivers;

- Purposeful and values-led, clearly related to organizational missions; and

- Nuanced and contextualized – helping people understand and relate skills to their own practice and setting.

2. Research Method

3. Open Foundations

4. Knowledge Production and Global Awareness

“Museums help us negotiate the complex world around us; they are safe and trusted spaces for exploring challenging and difficult ideas”.([55], p. 4)

5. Equity in Participation

6. Amplifying the Tenets of Global Digital Citizenship through Digital Culture

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borda, A.; Bowen, J. P. Turing’s Sunflowers: Public research and the role of museums. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2020: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 16–20 November 2020; Weinel, J., Bowen, J. P., Diprose, G., Lambert, N., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2020; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 32–39. [CrossRef]

- Digital Citizen Initiative. UNESCO. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/creativity/policy-monitoring-platform/digital-citizen-initiative (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Hamayel, H. J.; Hawamdeh, M. M. Methods Used in Digital Citizenship: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Digital Educational Technology. 2022, 2, ep2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital citizen. Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_citizen (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Mossberger, K.; Tolbert, C. J.; McNeal, R. S. Digital Citizenship: The Internet, Society, and Participation; The MIT Press, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Jones, L. M.; Mitchell, K. J. Defining and measuring youth digital citizenship. New Media & Society. 2016, 18, 1817–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negroponte, N. Being Digital; Hodder & Stoughton, 1995.

- Gilster, P. Digital Literacy; John Wiley: New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Berners-Lee, T. Weaving the Web; Orion Business Books, 1999.

- Ribble, M.; Bailey, G. Digital Citizenship in Schools; ISTE: Washington, DC, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Borda, A.; Gray, K.; Downie, L. Citizen Science Models in Health Research: An Australian Commentary. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics. 2019, 11, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribble, M. Digital Citizenship: Using technology appropriately, 2017. Available online: https://www.digitalcitizenship.net (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Ribble, M. Digital Citizenship in Schools: Nine Elements All Students Should Know, 3rd edition; International Society for Technology in Education, 2017.

- Rogers-Whitehead, C. Digital Citizenship in Schools: Teaching Strategies and Practice from the Field. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2019.

- Choi, M.; Cristol, D. Digital citizenship with intersectionality lens: Towards participatory democracy driven digital citizenship education. Theory Into Practice 2021, 60, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, E.; Simsek, A. New Literacies for Digital Citizenship. Contemporary Educational Technology. 2013, 4, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurbanoğlu, S.; Špiranec, S.; Grassian, E.; Mizrachi, D.; Catts, R., Eds. Information Literacy: Lifelong Learning and Digital Citizenship in the 21st Century. Communications in Computer and Information Science, volume 492. Springer, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Milic, N. Digitalising the Museum. In Handbook of Research on Museum Management in the Digital Era; Bifulco, F., Tregua, M., Eds.; Hersey, PA, Information Science Reference: Hersey, 2022; pp. 138–154. [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J. P. A New York Museums and Pratt partnership: Building Web collections and preparing museum professionals for the digital world. In MW2015: Museums and the Web, Chicago, USA, 8–11 April 2015; Archives & Museum Informatics, 2015. Available online: https://mw2015.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/a-new-york-museums-and-pratt-partnership-building-web-collections-and-preparing-museum-professionals-for-the-digital-world/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Malde, S.; Kennedy, A.; Parry, R. Understanding the digital skills & literacies of UK museum people: Phase Two Report. University of Leicester, UK, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson, M.; Craft, M.; Potter, T. Planetary grand challenges: a call for interdisciplinary partnerships. Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies 2019, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, L. C.; Yemini, M. Internationalization in public education, equity and hope for future citizenship. In Humanist futures: Perspectives from UNESCO Chairs and UNITWIN Networks on the futures of education; Paris, UNESCO, 2020.

- Global citizenship education: Topics and learning objectives. UNESCO, 2015. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000233240 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Watanabe-Crockett, L. What is a Global Digital Citizen and Why Does the World Need Them? Medium, 12 January 2017. Available online: https://medium.com/future-focused-learning/what-is-a-global-digital-citizen-and-why-does-the-world-need-them-8b94ace7803 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Allan, S.; Thorsen, E. (Eds.) Citizen Journalism: Global Perspectives. Peter Lang Publishing, 2009.

- Irwin, A. Citizen Science: A study of people, expertise and sustainable development. London, Routledge, 1995.

- Harrison, R.; Sterling, C. Reimagining Museums for Climate Action. London, Museums for Climate Action, 2021. Available online: https://www.museumsforclimateaction.org/mobilise/book (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Bowen, J. P.; Giannini, T. Digitalism: The new realism? In Proceedings of the EVA London 2014: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 8–10 July 2014; Ng, K., Bowen, J. P., McDaid, S., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2014; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 324–331. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J. P.; Giannini, T. Digitality: A reality check. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2021: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 5–9 July 2021; Weinel, J., Bowen, J. P., Borda, A., Diprose, G., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2021; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 12–19. [CrossRef]

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J. P. Digital Culture. In Museums and Digital Culture: New Perspectives and Research; Giannini, T., Bowen, J. P. Eds.; chapter 1, pp. 3–26; Cham, Springer, Series on Cultural Computing, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J. P. Museums and Digitalism. In Museums and Digital Culture: New Perspectives and Research; Giannini, T., Bowen, J. P. Eds.; chapter 2, pp. 27–46; Cham, Springer, Series on Cultural Computing, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Neuman, W. L. Social Research Methods Qualitative and Quantitative Approach, 8th edition. Pearson, 2021.

- Neilson, T.; Levenberg, L.; Rheams, D. Introduction: Research Methods for the Digital Humanities. In Research Methods for the Digital Humanities; Levenberg, L., Neilson, T.; Rheams, D., Eds.; Cham, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sonkoly, G.; Vahtikari, T.; Innovation in Cultural Heritage: For an Integrated European research policy. Working Paper. European Commission, Publications Office, Luxembourg, 2018. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/1dd62bd1-2216-11e8-ac73-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Bowen, J. P. The Virtual Library of museums. In Museum Collections and the Information Superhighway, ; Day, G., Ed.; London, Science Museum, 1995. 10 May.

- Bowen, J. P. Collections of collections. Museums Journal 1995, 95, 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gaia, G.; Boiano, S.; Bowen, J. P.; Borda, A. Museum websites of the first wave: The rise of the virtual museum. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2020: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 16–20 November 2020; Weinel, J., Bowen, J. P., Diprose, G., Lambert, N., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2020; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 24–31. [CrossRef]

- Reagle, J.; Koerner, J. (Eds.) Wikipedia @ 20. The MIT Press, 2020.

- Bowen, J. P.; Angus, J. Museums and Wikipedia. In MW2006: Museums and the Web; Albuquerque, Archives & Museum Informatics, 2006. Available online: https://www.archimuse.com/mw2006/papers/bowen/bowen.html (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Bowen, J. P. Wiki software and facilities for museums. In MW2008: Museums and the Web 2008, Montreal, Canada; Bearman, D.; Trant, J., Eds.; Archives & Museum Informatics, 2008. Available online: http://www.archimuse.com/mw2008/papers/bowen/bowen.html (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Bowen, J. P.; Fan, H. The Chengdu Biennale and Wikipedia Art Information. In Proceedings of EVA London 2022: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, London, UK, 4– 8 July 2022; Bowen, J. P., Weinel, J., Borda, A., Diprose, G., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2022; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 111–118. [CrossRef]

- Liu, A. H.-Y.; Bowen, J. P. Creating online collaborative environments for museums: A case study of a museum wiki. International Journal of Web Based Communities 2011, 7, 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borda, A.; Bowen, J. P. Virtual collaboration and community. In Virtual Communities: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools and Applications; Information Resources Management Association, Ed.; chapter 8.9, pp. 2600–2611. IGI Global, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Beler, A.; Borda, A.; Bowen, J. P.; Filippini-Fantoni, S.; The building of online communities: An approach for learning organizations, with a particular focus on the museum sector. In EVA 2004 London Conference Proceedings, University College London, UK; Hemsley, J., Cappellini, V., Stanke, G., Eds.; pp. 2.1–2.15, 2004. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/cs/0409055 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Wenger, E.; McDermott, R. A.; Snyder, W. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge. Harvard Business School Press, 2002.

- Digital Citizenship Museum. Community Virtual Library. Available online: https://communityvirtuallibrary.org/digital-citizenship-museum/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Dorman, D. Open Source Software and the Intellectual Commons. American Libraries 2002, 33, 51–54. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25648551 (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Powell, A. Democratizing production through open source knowledge: from open software to open hardware. Media, Culture & Society 2012, 34, 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, R.; Walsh, J.; Open Knowledge: Promises and Challenges. In The Digital Public Domain: Foundations for an Open Culture, 1st edition; de Rosnay, M. D., De Martin, J. C., Eds.; Volume 2, pp. 125–132. Open Book Publishers, 2012. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5vjsx3.13 (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Borda, A.; Beler, A.; Development of a Knowledge Site in Distributed Information Environments. In Proceedings. ICHIM ’03, L’ecole du Louvre, Paris, September 2003. Archives & Museums, 2003. Available online: http://www.archimuse.com/publishing/ichim03/085C.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Bowen, J.; Angus, J.; Bennet, J.; Borda, A.; Hodges, A.; Filippini-Fantoni, S.; Beler, A. The Development of Science Museum Websites: Case Studies. In E-learning and Virtual Science Centers; Hin, T. W., Subramaniam, R., Eds.; Section 3: Case Studies, chapter XVIII, pp. 366–392. Hershey, PA, Idea Group Publishing, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

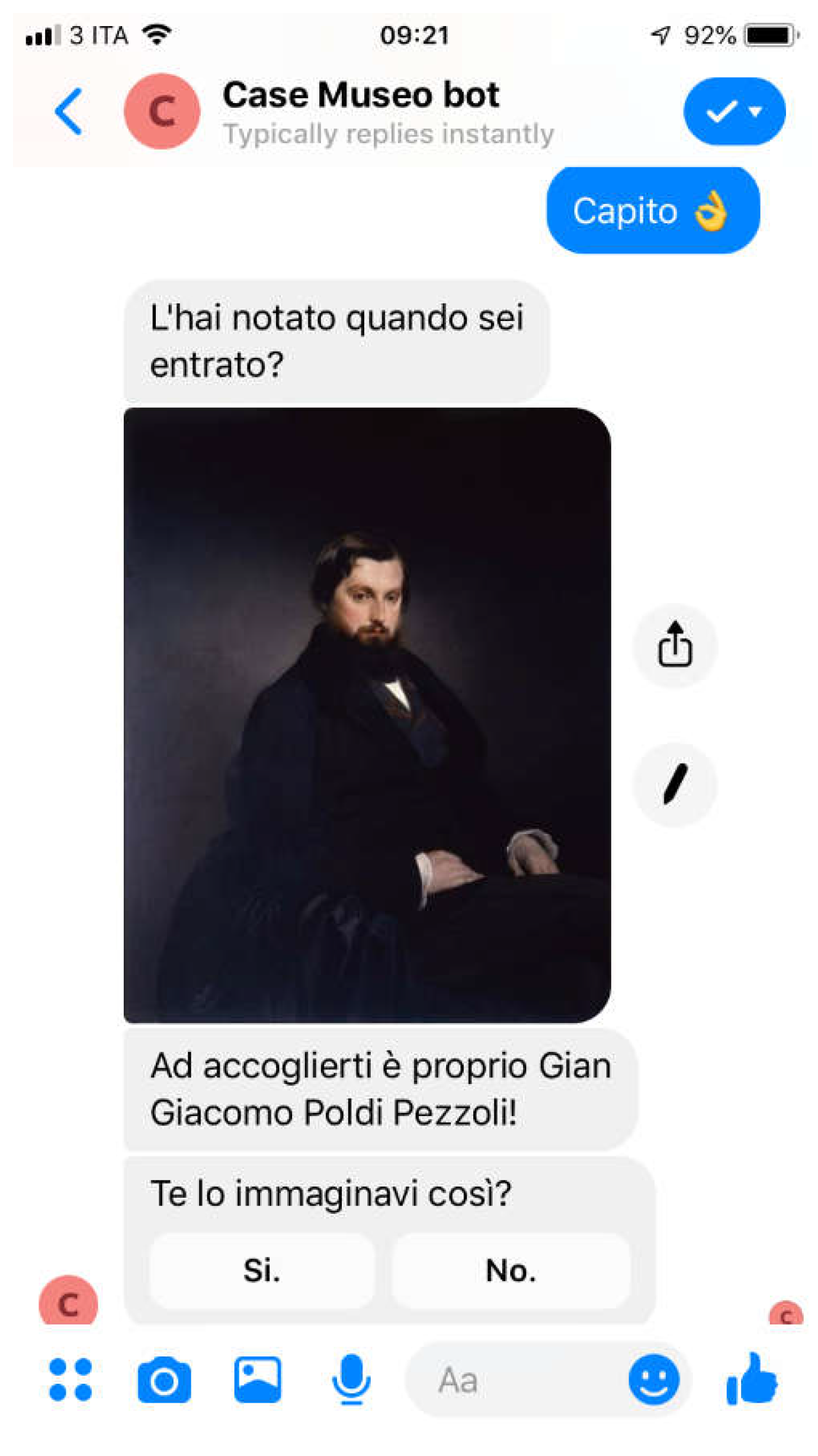

- Gaia, G.; Boiano, S.; Borda, A. Engaging Museum Visitors with AI: The Case of Chatbots. In Museums and Digital Culture: New Perspectives and Research; Giannini, T., Bowen, J. P. Eds.; chapter 15, pp. 301–329; Cham, Springer, Series on Cultural Computing, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Jones-Garmil, K. (Ed.) The Wired Museum: Emerging Technology and Changing Paradigms. American Association of Museum, 1997.

- Museums Taskforce Report and Recommendations. Museums Association, London, UK, 2018. Available online: https://ma-production.ams3.digitaloceanspaces.com/app/uploads/2020/08/17073208/Museums-Taskforce-Report-and-Recommendations.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Hedges, M.; Dunn, S. Academic Crowdsourcing in the Humanities: Crowds, communities, and co- production. Cambridge, MA, Elsevier Science, 2017.

- Hecker, S.; Haklay, M.; Bowser, A.; Makuch, Z.; Vogel, J.; Bonn, A. (Eds.) Citizen Science: Innovation in Open Science, Society and Policy. London, UCL Press, 2018.

- Hintz, A.; Dencik, L.; Wahl-Jorgensen, K. Digital Citizenship in a Datafied Society. Polity, 2018.

- Ridge, M. (Ed.) Crowdsourcing our Cultural Heritage. London, Ashgate, 2024.

- Tseng, Y.-S. Rethinking gamified democracy as frictional: a comparative examination of the Decide Madrid and vTaiwan platforms. Social & Cultural Geography. [CrossRef]

- Borda, A.; Bowen, J. P. Smart cities and cultural heritage: a review of developments and future opportunities. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2017: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 10–13 July 2017; Bowen, J. P., Diprose, G., Lambert, N., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2017; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 9–18. [CrossRef]

- Borda, A.; Bowen J., P. (2019) Smart Cities and Digital Culture: Models of Innovation.. In Museums and Digital Culture: New Perspectives and Research; Giannini, T., Bowen, J. P. Eds.; chapter 27, pp. 523–549; Cham, Springer, Series on Cultural Computing, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Beazley, I.; Bowen, J. P.; Liu, A. H.-Y.; McDaid, S. Dulwich OnView: An art museum-based virtual community generated by the local community. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2010: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 5–7 July 2010; Seal, A., Bowen, J. P., Ng, K., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2010; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 79–86. [CrossRef]

- Dangerfield, M. B. Power to the People: The rise and rise of Citizen Journalism. Tate, UK, 2015. Available online: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/photojournalism/power-people (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Citizen Journalism: Sign of the Times. The Autry Museum, Los Angeles, USA, 2018 Available online:. Available online: https://theautry.org/citizen-journalism (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Copeland, B. J.; Bowen, J. P.; Sprevak, M.; Wilson, R. J., et al. The Turing Guide. Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Black, S.; Bowen, J. P.; Griffin, K. Can Twitter Save Bletchley Park? In MW 2010: Museums and the Web Conference, Denver, Colorado, USA; Archives & Museum Informatics, 2010. Available online: https://www.museumsandtheweb.com/biblio/can_twitter_save_bletchley_park.html (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Mundt, M.; Ross, K.; Burnett, C. M. (2018). Scaling Social Movements Through Social Media: The Case of Black Lives Matter. Social Media + Society 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Díaz, A. & Fernández-Prados, J.S. (2022) Young digital citizenship in #FridaysForFuture. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies 2022, 44, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, T. Contested Space: Activism and Protest. In Museums and Digital Culture: New Perspectives and Research; Giannini, T., Bowen, J. P. Eds.; chapter 5, pp. 91–111; Cham, Springer, Series on Cultural Computing, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J. P. Art and activism at museums in a post-digital world. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2019: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 8–12 July 2019; Weinel, J., Bowen, J. P., Diprose, G., Lambert, N., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2019; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 27–35. [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Bowen, J. P. The Weiguan Culture Phenomenon in Chinese Online Activism. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2021: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 5–9 July 2021; Weinel, J., Bowen, J. P., Borda, A., Diprose, G., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2021; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 129–136. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L. Museums as Sources of Information and Learning. Open Museum Journal 2006, 8, https://publications.australian.museum/museums-as-sources-of-information-and–learning/. Available online: https://publications.australian.museum/museums-as-sources-of-information-and-learning/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Kelly, L. Engaging Museum Visitors in Difficult Topics Through Socio-cultural Learning and Narrative. In Hot Topics, Public Culture, Museums; Cameron, F., Kelly, L., Eds.; pp. 194–210. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010. http://www.c-s-p.org/flyers/Hot-Topics--Public-Culture--Museums1-4438-1974-3.htm. (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Kelly, L. The Connected Museum in the World of Social Media. In Museum Communication and Social Media: The connected museum; Drotner, K., Schroder, K., Eds.; pp. 54–71. London, Routledge: 2013.

- Simon, N. The Participatory Museum, 2010. Available online: http://www.participatorymuseum.org (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Dilenschneider, C.; People Trust Museums More Than Newspapers. ColleenDilenschneider, 26 April 2017. Available online: https://www.colleendilen.com/2017/04/26/people-trust-museums-more-than-newspapers-here-is-why-that-matters-right-now-data/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Dilenschneider, C.; More People Trust Museums Now Than Before the Pandemic (DATA). ColleenDilenschneider, 1 March 2023. Available online: https://www.colleendilen.com/2023/03/01/more-people-trust-museums-now-than-before-the-pandemic-data/ (accessed on 11 April 2023).

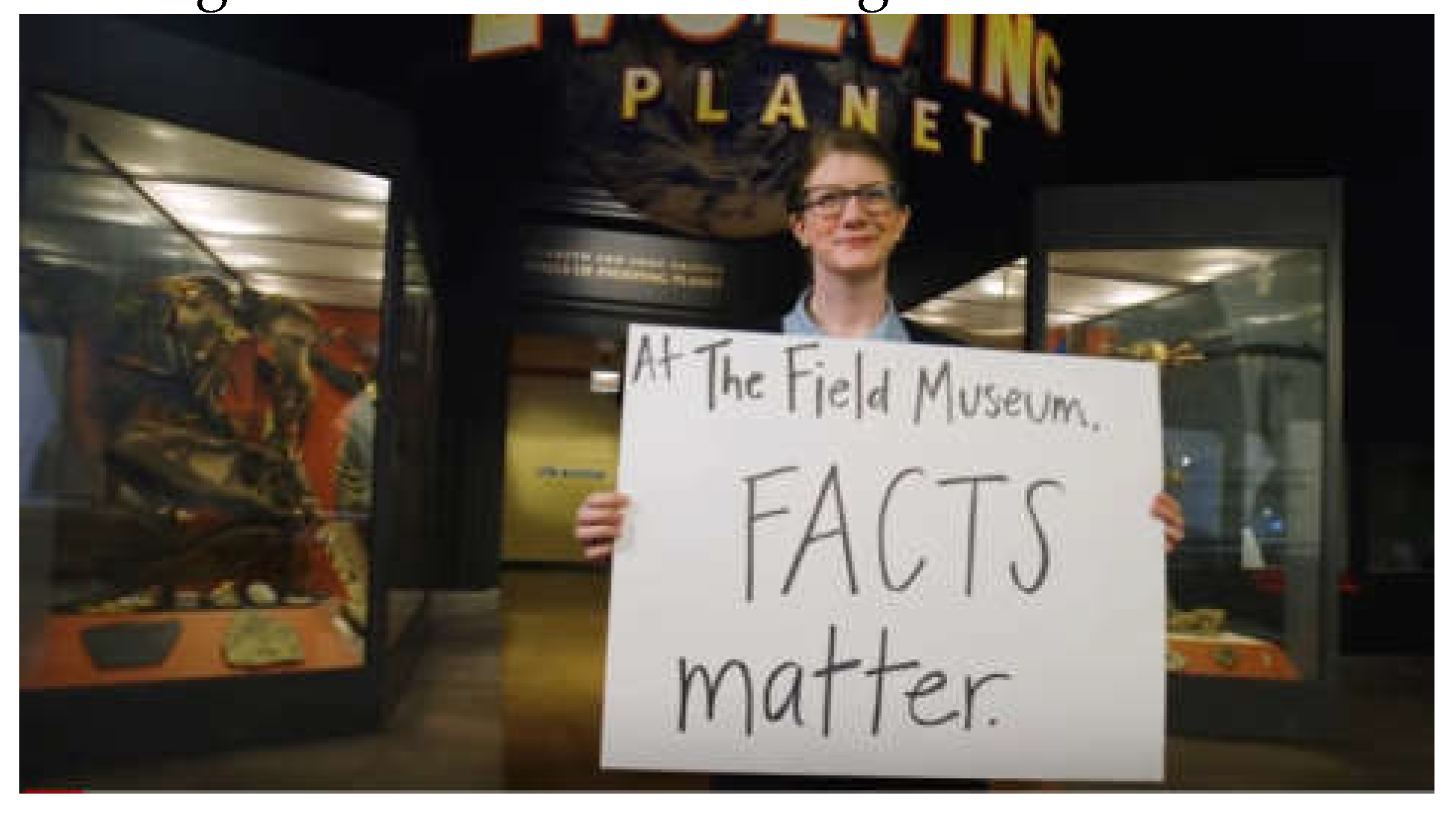

- #DayOfFacts – Museums and cultural/scientific institutions reminding the public that facts matter. DayOfFacts, WordPress, 17 February 2017. Available online: https://dayoffacts.wordpress.com (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Johnson, H. Adorno and climate science denial: Lies that sound like truth. Philosophy & Social Criticism 2020, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorno, F.; Stronger Than the Storm: Museums in the Age of Climate Change. Western Museums Association (WMA), USA. Available online: https://westmuse.org/articles/stronger-storm-museums-age-climate-change (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- @altNOAA. Twitter. Available online: https://twitter.com/altNOAA (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Miller, P.; A new mission for museums: Report calls for institutions to help battle ‘fake news’. The Herald, 5 March 2018. Available online: https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/16064183.new-mission-museums-report-calls-institutions-help-battle-fake-news/ (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Boiano, S.; Borda, A.; Gaia, G. Participatory innovation and prototyping in the cultural section: A case study. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2019: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 8–12 July 2019; Weinel, J., Bowen, J. P., Diprose, G., Lambert, N., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2019; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 18–26. [CrossRef]

- Mutibwa, D. H.; Hess, A.; Jackson, T. Strokes of serendipity: Community co-curation and engagement with digital heritage. Convergence 2020, 26, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, J.; From Social Media to the Social Museum. Nordic Center of Heritage Learning. The Nordic Centre of Heritage Learning and Creativity, Östersund, Sweden, 2013. Available online: http://nckultur.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/From_Social_Media_to_a_Social_Museum_Jasper_Visser.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Warschauer, M. Technology and Social Inclusion: Rethinking the Digital Divide. The MIT Press, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Bonacchi, C.; Bevan, A.; Keinan-Schoonbaert, A.; Pett, D.; Wexler, J. Participation in heritage crowdsourcing. Museum Management and Curatorship 2019, 34, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janes, R. R. The Mindful Museum. Curator: The Museum Journal 2010. 53, 325–338. [CrossRef]

- Filip, F. G.; Ciurea, C.; Dragomirescu, H.; Ivan, I. Cultural heritage and modern information and communication technologies. Technological and Economic Development of Economy 2015, 21, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahne, J.; Hodgin, E.; Eidman-Aadahl, E. (2016). Redesigning civic education for the digital age: Participatory politics and the pursuit of democratic engagement. Theory & Research in Social Education 2016. 44, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Disinfodemic: Deciphering COVID-19 disinformation. UNESCO, 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374416 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- UNESCO Report: Museums around the world in the face of COVID-19. UNESCO, 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373530 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Holcombe-James, I. COVID-19, digital inclusion, and the Australian cultural sector: A research snapshot. Digital Ethnography Research Centre, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bridging the Digital Gender Divide: Include, Upskill, Innovate. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2018. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/digital/bridging-the-digital-gender-divide.pdf (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Dirksen, A. , (2020) Decolonizing Digital Spaces. In Citizenship in a Connected Canada: A Research and Policy Agenda; Dubois, E.; Martin-Bariteau, F., Eds.; Ottawa, ON, University of Ottawa Press, 2020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3620493 (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Shoenberger, E. What does it mean to decolonize a museum? Museum Next, 23 February 2022. Available online: https://www.museumnext.com/article/what-does-it-mean-to-decolonize-a-museum/ (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Excellence in DEAI: 2022 Report from the Excellence in DEAI Task Force. American Alliance of Museums, 2 August 2022. Available online: https://www.aam-us.org/2022/08/02/excellence-in-deai-report/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Indigenous Digital Inclusion Plan – discussion paper. National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA), Australia, September 2021. Available online: https://www.niaa.gov.au/resource-centre/indigenous-affairs/indigenous-digital-inclusion-plan-discussion-paper (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Mortati, M.; Magistretti, S.; Cautela, C.; Dell’Era, C. Data in design: How big data and thick data inform design thinking projects. Technovation 2023, 122, 102688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, B. The Possible Museum: Anticipating Future Scenarios. In Addressing the Challenges in Communicating Climate Change Across Various Audiences; Leal Filho, W., Lackner, B., McGhie, H., Eds.; pp 443–456. Springer, Cham, Climate Change Management, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ceccaroni, L.; Bibby, J.; Roger, E.; Flemons, P.; Michael, K.; Fagan, L.; Oliver, J. L. (2019) Opportunities and risks for citizen science in the age of artificial intelligence. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 2019, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiano, S.; Borda, A.; Gaia, G.; Rossi, S.; Cuomo, P. Chatbots and new audience opportunities for Museums and Heritage Organisations. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2018: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 9–13 July 2018; Bowen, J. P., Weinel, J., Diprose, G., Lambert, N., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2018; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 164–171. [CrossRef]

- Merritt, E.; Chatting About Museums with ChatGPT. American Alliance of Museums, 25 January 2023. Available online: https://www.aam-us.org/2023/01/25/chatting-about-museums-with-chatgpt/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), United Nations, 23 November 2021. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/UNESCO.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Giannini, T.; Bowen, J. P.; Michaels, C.; Smith C., H. Digital Art and Identity Merging Human and Artificial Intelligence: Enter the Metaverse. In Proceedings of EVA London 2022: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts, London, UK, 4– 8 July 2022; Bowen, J. P., Weinel, J., Borda, A., Diprose, G., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2022; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, G.; Ingram, J.; Lost in the metaverse? How digital anthropology can help leaders navigate uncertain futures. World Economic Forum, 9 March 2023. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/03/digital-anthropology-leaders-navigate-metaverse (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Barba, B.; Mat, V. L.-A.; Gomez, A.; Pirovich, J. Discussion Paper: First Nations' Culture in the Metaverse. SSRN, 18 April 2022. 18 April. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.; This chart shows how big the metaverse market could become. World Economic Forum, 7 February 2023. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/02/chart-metaverse-market-growth-digital-economy (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Cameron, F. R.; Neilson, B., Eds. Climate Change and Museum Futures. London, Routledge, 2015. Cameron, F. R.; Neilson, B. (Eds.).

- Janes, R. R.; The end of neutrality: A modest manifesto. Council of Australian Museum Directors, Australia, 17 March 2016. Available online: https://camd.org.au/end-of-neutrality/ (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Bowen, J. P.; Giannini, T. (2019) The Digital Future of Museums. In Museums and Digital Culture: New Perspectives and Research; Giannini, T., Bowen, J. P. Eds.; chapter 28, pp. 551–577; Cham, Springer, Series on Cultural Computing, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J. P. A personal view of EVA London: Past, present, future. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2020: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 16–20 November 2020; Weinel, J., Bowen, J. P., Diprose, G., Lambert, N., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2020; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 8–15. [CrossRef]

- Borda, A.; Bowen, J. (2021). The Rise of Digital Citizenship and the Participatory Museum. In Proceedings of the EVA London 2021: Electronic Visualisation and the Arts. London, UK, 5–9 July 2021; Weinel, J., Bowen, J. P., Borda, A., Diprose, G., Eds.; BCS: Swindon, UK, 2021; Electronic Workshops in Computing. ScienceOpen. pp. 20–27. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).