Preprint

Article

Designing a Multi-Epitope Subunit Vaccine against VP1 Major Coat Protein of JC Polyomavirus

This version is not peer-reviewed.

Submitted:

27 April 2023

Posted:

27 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

Abstract

The JC polyomavirus virus (JCPyV) affects more than 80% of the human population in their early life stage. It mainly affects immunocompromised individuals where virus replication in oligodendrocytes and astrocytes may lead to fatal progressive multifocal encephalopathy (PML). Virus protein 1 (VP1) is one of the major structural proteins of the viral capsid, responsible for keeping the virus alive in the gastrointestinal and urinary tracts. VP1 is often targeted for antiviral drug and vaccine development. Similarly, this study implied immunoinformatics and molecular dynamics simulation-based approaches to design a multi-epitope subunit vaccine targeting JCPyV. The VP1 protein epitopic sequences, which are highly conserved, were used to build the vaccine. This designed vaccine includes two adjuvants, five HTL epitopes, six CTL epitopes, and two linear BCL epitopes to stimulate cellular, humoral, and innate immune responses against JCPyV. Furthermore, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation (100ns) studies were used to examine the interaction and stability of the vaccine protein with TLR4. Trajectory analysis showed that the vaccine and TLR4 receptor form a stable complex with the vaccine protein. Overall, this study contributed to the path of vaccine development against JCPyV and may prevent PML from happening. However, this study needs experimental validation to conclude our findings.

Keywords:

Progressive Multifocal Encephalopathy (PML)

; JC Polyomavirus

; VP1 protein

; Immunoinformatics

; molecular dynamics simulation

1. Introduction

Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML), a demyelinating disease affecting the central nervous system, is caused by the John Cunningham virus (JCV), also known as Human Polyomavirus-2 [1]. The mode of transmission of JC polyomavirus (JCPyV) is given in Figure 1. It is a hemagglutinating, widespread, and species-specific disease condition. The virus has a seroprevalence between 40-60%. While in kids, seroprevalence is only 10–20% and significantly rises in the following years [2]. The virus can be classified into subtypes depending on how widely it has spread among diverse human populations. Types 1 and 4 typically affect Europeans, 3 and 6 affect the African population, and type 7A typically affects South East Asians [3].

JCV is a non-enveloped virus comprised of 72 viral capsomeres with icosahedral symmetry (Figure 2A,B), each containing a circular dsDNA genome. The viral genome has two coding domains and is approximately 5000 base pairs long [5]. For example, the first viral gene encodes large and small tumor antigens. The second region, in contrast, encodes for the three main structural proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3, as well as an auxiliary regulatory protein known as agnoprotein [6]. A regulatory non-coding control region (NCCR) separates the early and late viral gene regions. The NCCR contains transcription factor-binding sites, host cell-specific DNA, the replication origin, and regulatory areas focusing on early and late transcription [7].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the significance of the primary capsid protein VP1 in promoting JCV attachment to host cell receptors and starting a viral infection [8,9,10]. The oligosaccharide lactoseries tetrasaccharide C (LSTc), composed of 2,6-linked NeuNAc, is the only one to which JCV-VP1 interacts. Thus, LSTc functions as a JCV receptor [11]. It has been discovered that VP1 also interacts with the 5-HT2AR serotonin receptor. However, it is unclear how the 5-HT2AR functions in infections [12]. The VP1 protein also facilitates viral assembly inside the host cell nucleus [13]. Because of this, VP1 is a crucial target in creating vaccines and drugs to treat JCV infection.

The recent SARS-CoV-2 outbreak [14] demonstrated the importance of vaccination when the entire world was waiting to develop a potent vaccine to end up the pandemic. Moreover, recent events have highlighted the importance of vaccination. Earlier, the Immunoinformatics approach was used to develop the vaccine against various viral infections [15,16,17,18]. Recently, the synthetic binding proteins database has been developed, which could lay a solid foundation for future research, diagnosis, and therapy development [19]. We have attempted to design a suitable and stable vaccine for preventing JCPyV-induced PML. Using an innovative immuno-informatics method, VP1 protein was targeted to construct a subunit vaccine. Various web servers were utilized to predict different epitopes for the vaccine construction, and adjuvants and linkers were included. It was determined whether the developed vaccine had strong antigenic and non-allergenic qualities that could stimulate an effective immune response against the JCPyV. The vaccine binding mechanism and stability with the TLR4 receptor were further explored using molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations. The immunological simulation proves the vaccine's durability and antibody generation.

2. Methodology

2.1. Sequence retrieval and analysis

The VP1 capsid protein's amino acid sequence (UniProt ID: P03089) was obtained from the UniProt database in FASTA format [20]. The physical and chemical characteristics of the chosen proteins were ascertained using the ExPASy ProtParam program [21]. The antigenicity of the protein was calculated using the VaxiJen v2.0 server [22]. This server performs antigenicity analysis using the physiochemical characteristics of the protein. The NCBI-BLAST program determined the homology between the VP1 coat protein and other animals, primarily humans. Their sequences were further matched, and the phylogenetic tree was created using the NJ technique of the MEGA11 program [23] with default settings and 1,000 bootstrap replicators (Figure 2C).

2.2. B cell Epitopes Prediction

The Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) and analysis resource for B cell epitope prediction server was used to predict linear B cell epitopes. To anticipate the epitopes, the Kolaskar and Tongaonkar approach was employed [24]. It uses amino acids' physical and chemical characteristics to predict the B-cell epitopes. The VP1 main capsid protein's amino acid sequence was provided in the FASTA format with a threshold value of 1.022. Further submissions of the predicted B-cell epitopes to the ToxinPred service were made to verify their non-toxicity [25]. VaxiJen v 2.0 [22] server was used to predict the antigenicity of the epitopes, and the AllerTOP v.2.0 server [26] to sort the non-allergic epitopes.

2.3. HTL Epitopes Prediction

Antigen-presenting cells express MHC-II molecules on their surface, presenting antigenic peptides to the T-cell receptor, which coordinates the outcome of the host’s immune response. The MHC-II specific epitopes for the VP1 capsid protein were identified using Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) MHC Class II tool [24]. This tool uses NN-align-2.3 (netMHCII-2.3) algorithm to predict the same. The NN-align-2.3 (netMHCII-2.3) method predicts the peptides using an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) [27]. The predicted scores are given in IC50 values (nM) and as a percentile rank. The sorted peptides were further scanned for antigenicity (VaxiJen v 2.0) [22], allergenicity (AllerTOP v.2.0) [28], and toxicity (ToxinPred) parameters [25].

2.4. CTL Epitopes Prediction

The prediction of the CTL epitopes aims to identify the key peptides which stimulate the CD8+ T cells. The Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) MHC Class I tool was used to identify the CTL Epitopes in accordance with the ANN [24,25,26,27]. The neural network is a most significant algorithm to sort the peptides that bind strongly to HLA molecules, confirming that the higher-order sequence correlation signal is mainly seen in high-binding peptides. The three essential parameters that were concentrated while predicting the epitopes are MHC binding affinity, proteasome cleavage, and TAP transports. The results obtained were further scanned for antigenicity, allergenicity, and toxicity.

2.5. Designing of the vaccine construct and physiochemical analysis

The selected B cell, HTL, and CTL epitopes were assembled in a sequence-wise manner. Different connecting linkers were used to link the epitopes. The B cell, HTL, and CTL epitopes were linked by KK, GPGPG, and AAY linkers, respectively [6]. The N terminal of the vaccine construct is linked with Human β defensin (45 amino acids) and LL37 sequence (37 amino acids) to enhance the vaccine efficacy and immunogenicity. They were linked together by the EAAAK linker. Human β defensin behaves as an antimicrobial agent as well as an immunomodulator [29]. LL37 is a cathelicidin family member and has antimicrobial activity [30]. The novel formulation of Human β defensin and LL37 as a ‘combination adjuvant’ generates high antigenicity and act interdependently to produce Th1-based adaptive immune response [31]. The physiochemical analysis of the vaccine construct was performed by using ExPASy ProtParam tool [21]. The sequence was also subjected to antigenicity and allergenicity prediction. The design of the final vaccine construct is shown in Figure 3A.

2.6. Tertiary structure prediction and validation

The 3-D structure of the vaccine construct provides valuable information for understanding and regulating biological functions. The 3-D structure of the vaccine construct was predicted using the GalaxyWEB protein structure prediction server [32]. The server predicted the 3-D structure from the vaccine construct using template-based modeling (TBM) and refined the loop and the terminus regions. TBM is a method for predicting the three-dimensional structure of a protein by aligning its amino acid sequence with a known, similar protein structure (template) from a protein database. This approach assumes that proteins with similar sequences tend to have similar structures. In the context of vaccine design, TBM can be used to create a 3D model of vaccine construct, which is proposed to elicit an immune response. The structure was validated by generating Ramachandran Plot through the PDBsum server [33].

2.7. Molecular docking of vaccine construct with TLR-4

TLR4 signal pathway is essential in initiating the innate immune response [34] and is further responsible for cytokine release [35]. Earlier studies showed that recognition of mouse polyomavirus (MPyV) by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), a sensor of the innate immunity system, induces the production of interleukin 6 (IL-6) and other cytokines without inhibiting virus multiplication [36]. To investigate the binding mode of the vaccine construct with TLR4, a molecular docking study was performed using the PatchDock server (http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/PatchDock) [37]. The crystal structure of TRL4 (3FXI.pdb) was retrieved from the protein database. The docking results from the PatchDock were further refined using the FireDock server (http://bioinfo3d.cs.tau.ac.il/FireDock/php.php) [38]. The least binding energy vaccine constructs docked with the receptor TLR4 was considered as a starting structure for molecular dynamics simulation.

2.8. Molecular Dynamic Simulations

Molecular dynamics simulations were performed using Gromacs2021.3 [39] to explore the refined binding mode of vaccine construct with TLR4. For the simulation, amber ff99SB force field parameters were used. The simulation systems were solvated using a TIP3P water module in a cubic box of 10 Å, and the system was neutralized by adding the required number of counter ions. Using the ‘Parmed tool’, the amber ‘topology’ and ‘co-ordinate’ files were converted into Gromacs companion ‘top’ and ‘gro’ files, similar to an earlier study [40]. The energy minimization was performed with the steepest descent (5000 steps) and the conjugate gradient (2000 steps) methods. To equilibrate all the systems, 1ns NVT and 1 ns NPT simulations were performed. The equilibrated system was further used for the production molecular dynamics simulation for 100 ns time steps, using the cut-off distance of 1.0 nm with a Fourier spacing of 0.16 nm and an interpolation order of 4 was used, and the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method was used to calculate the long-range electrostatic interactions [41]. The simulated trajectories and snapshots were further analyzed and visualized using ‘gmx’ tools of Gromacs [42] and visualized by PyMol software [43].

2.9. Immune simulation

To understand the immune response and immunogenicity of the vaccine protein, the C-IMMSIM server (https://krake n.iac.rm.cnr.it/C-IMMSIM/) was used [44]. Immunogenicity refers to the ability of a vaccine to induce an immune response, specifically the production of antibodies that recognize and neutralize the target pathogen. The strength and quality of the immune response, or immunogenicity, is a key factor in determining the efficacy of a vaccine. A vaccine with high immunogenicity is more likely to protect against the disease it is designed to prevent. The simulation steps were 1,000, the simulation quantity was 10μL, and the random seed was 12,345. The C-IMMSIM uses position-specific scoring matrices for peptide prediction derived from machine learning techniques for predicting immune interactions. Here, we predict the interaction of vaccine candidates with immune receptors to boost humoral and cellular immune responses.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sequence Retrieval and Analysis

The VP1 major capsid protein sequence was collected from the UniProt database (UniProt ID: P03089) in FASTA format. The antigenic property of the VP1 protein sequence was found to be 0.4042, which is equal to the threshold value of 0.4. The physicochemical analysis revealed that the protein contains 354 amino acids. The molecular weight was found to be 39.6 kDa, the isoelectric point was obtained as 5.79, and the instability index was calculated to be 33.79, which classifies that the protein is stable. The aliphatic index of 75.88 indicated that the protein is stable over a wide range of temperatures. The estimated half-life was 30 hrs in mammalian reticulocytes (in vitro), 20 hours in yeast (in vivo), and 10 hours in Escherichia coli (in vivo).

Furthermore, the phylogenetic analysis study was performed to check the evolutionary relationship with polyomavirus. The phylogenetic analysis showed that VP1 coat protein clustered together in a single clade, having the most common ancestry, and a less branching pattern revealed minimum evolutions. Therefore, the vaccine designed against one strain can be used for all polyomavirus strains.

3.1.1. B cell Epitopes Prediction

The B cell epitopes can induce humoral immunity, as they get recognized by the B-cell receptors. In total, 14 epitopes were predicted by the IEDB B cell epitope prediction server. These epitopes were further analyzed for antigenicity, allergenicity, and toxicity. The epitopes with the highest antigenic score, non-allergenic and non-toxic epitopes, were selected for the vaccine construct and listed in Table 1. These vaccine epitopes are crucial for the immunological response.

3.1.2. HTL Epitopes Prediction

The HTL epitopes stimulate a CD4+ helper response which further helps to develop protective CD8+ T-cell memory and activates B-cells for antibody generation. Hence, to produce the CD4+ T-cell epitopes, the IEDB MHC Class II epitope prediction server was used [24]. A total of 9047 HTL epitopes was predicted by the IEDB MHC Class II epitope prediction tool [24]. The top five epitopes, which were antigenic, non-allergic, and non-toxic, were chosen to design the vaccine construct and listed in Figure 3A and Table 2.

3.1.3. CTL Epitopes Prediction

To develop long-term immunity and eliminate the circulating virus and virus-infected cells, CD8+ T-cells play a crucial role. A total of 16,606 CTL epitopes were predicted by the IEDB MHC Class I epitope prediction tool. The top five epitopes, which were antigenic, non-allergic, and non-toxic, were chosen to design the vaccine construct and listed in Table 3.

3.1.4. Designing of the linear vaccine construct and physiochemical analysis

The vaccine construct consists of 284 amino acids with a molecular weight of 31.39 kDa, as shown in Figure 3A. The instability index was calculated as 32.67, indicating that the protein is stable over a wide temperature range. The vaccine construct was also found to be antigenic, non-allergenic, and non-toxic. The estimated half-life was predicted to be 30 hours in mammalian reticulocytes, 20 hours in yeast (in vivo), 10 hours in Escherichia coli. The vaccine construct was confirmed to be antigenic, non-allergic, and non-toxic in behavior.

3.1.5. Vaccine tertiary structure prediction and validation

The GalaxyWEB server [32] was used to predict the three-dimensional structure of the vaccine construct as shown in Figure 3B,C. The 3D model was validated using the Ramachandran plot generated by using the PDBSum server, as shown in Figure 3D. It showed that 97% of residues are present in the most favored region and additionally allowed region, whereas only 0.9% in the generously allowed region and 2.2% in the disallowed region. The stereochemical quality of the vaccine construct was found to be good, hence further used for molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation study.

3.1.6. Molecular Docking of vaccine construct with TLR-4

To explore the binding mode of vaccine construct with TLR4 receptor, molecular docking was performed using the PatchDock server [37]. The least energy 10 docked outputs were selected and fed further to FireDock for refinement [38]. The PIMA server [45] was used to understand the vaccine and TRL4 complex stability, the complex is stabilized by the electrostatic (-12.7055 kJ/mol), and van der Waals energy (-95.8678 kJ/Mol) and the total stabilizing energy is -108.5733 kJ/Mol. The final output generated by FireDock, with the lowest global energy value of solution number of vaccine-TRL4 (Figure 4A), was considered starting conformation for molecular dynamics simulation. The TLR4-and vaccine complex is stabilized by mainly hydrogen bonding and non-bonding interactions. The details of the residues involved in the TLR4-Vaccine complex interactions are shown in Figure 4B,C.

3.2. Molecular Dynamic Simulations

To explore the refined binding mode of the vaccine with the TRL4 receptor, molecular dynamics simulation was performed for 100 ns using Gromacs2021.3 [42]. The stability of the complex is checked by plotting the root mean square deviation of backbone atoms as shown in Figure 5A. The RMSD plot reveals the stability of the TLR4-Vaccine complex, and RMSD is found to fluctuate below 1 nm (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the protein compactness was studied using the radius of gyration (Rg), as shown in Figure 5B. Rg plot revealed the stable complex and compact state of the TLR4 and vaccine construct. Furthermore, the root mean square fluctuations were calculated for the vaccine and TLR4 chain A and B, as shown in Figure 5C,D.

The RMSF plot reveals the movement of Cα atoms during the simulations. The highly flexible region shows higher RMSF, while the constrained regions show a lower value of RMSF. The RMSF plot shows that vaccine residues from the region 170 to 270 were found to be less fluctuations and were involved in the binding with the TLR4 receptor. Also, the TLR4 chain B residues from the region 0 to 250 were found to have less fluctuations and were involved in the binding with the vaccine construct, as shown in Figure 5C. Furthermore, the chain A residues from regions 300 to 400 were found to have less fluctuations and were involved in the binding with vaccine residues, as shown in Figure 4C and Figure 5C.

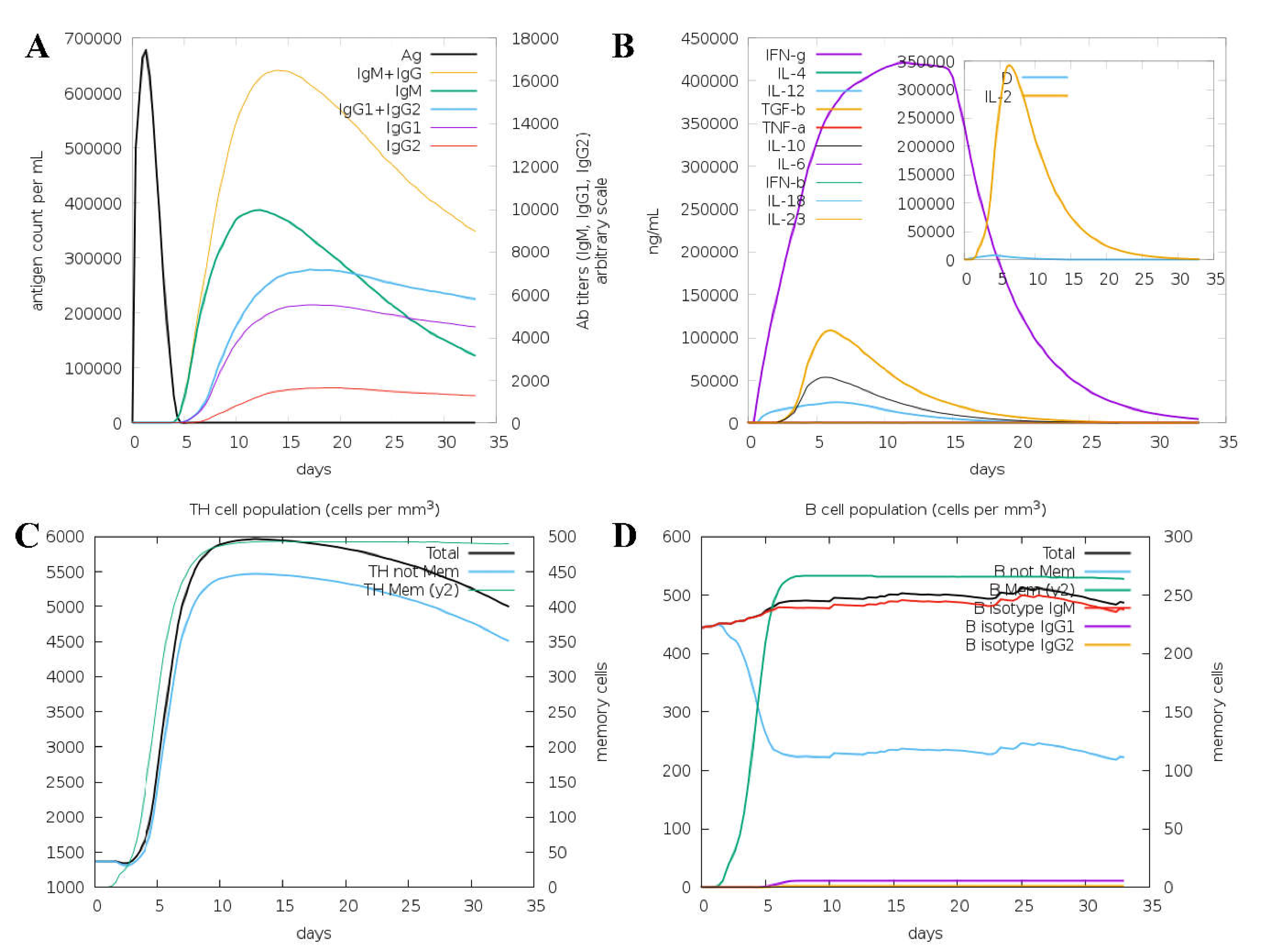

3.3. Immune system simulation

To understand the immune response to the vaccine protein, the C-ImmSim server was used. Here, the antigen and immunoglobulins, cytokine production, Th cell population, and B cell population parameters were studied and shown in Figure 6. The primary host response is indicated by increased IgM and IgG levels, as shown in Figure 6A. In addition, increased levels of IgG1, IgG2, IgG, and T and B cell populations indicate a secondary response to the antigen, as shown in Figure 6B,C. The focus of cytokines and interleukins was also considerably enhanced after immunization, as shown in Figure 6B. The results evaluation indicated that the vaccine could initiate the antigen-stimulated, more robust immune response and be safe.

4. Discussion

PML is a lethal CNS demyelinating disease caused by the human JCPyV. It is prevalent exclusively in individuals with therapeutic immunomodulatory antibodies to treat conditions like multiple sclerosis (MS), transplant recipients, and others. The high seroprevalence of JC virus and reduced incidence of viral infection is common and persists in an asymptomatic manner, gradually leading to viral reactivation causing PML [10,46].

For JCPyV, the archetype VP1 is the cause of viral persistence in the urinary and gastrointestinal tract. It results in virus infection through urine and feces. The JCPyV-PML mutations are located in the external loops of the VP1 protein [47]. JCPyV’s carrying VP1 mutations resulting in altered receptor binding and antibody escape can turn an asymptomatic infection in an organ-like kidney to a deadly brain disease [47]. The disease mechanism of JC and PML still has various unanswered queries. Currently, few treatment options are available for JC-induced PML, even though it is a rapidly progressing and devastating disease [10].

Previous studies have shown that a multi-epitope vaccine is an ideal approach for the treatment and prevention of viral diseases caused [48,49,50,51,52]. Different approaches are used to construct multi-subunit vaccines compared to the classical and single-subunit vaccines [15,16,17,18]. Multi-subunit vaccine designing needs MHC-I and MHC-II restricted epitopes capable of getting recognized by T Cell Receptors (TCRs) of multiple clones by various T-cell subsets imparting strong cellular immune responses. In comparison, B-cell epitopes impart strong humoral immune responses against appropriate antigens for expanding the spectra of viral treatment, suitable adjuvants, and linkers for immunogenicity enhancement [51,52,53]. Thus, we focused on constructing a multi-epitope vaccine against PML caused by JCPyV using Immunoinformatics and molecular modeling approach.

For designing an efficacious subunit vaccine, identifying conserved HTL and CTL epitopes was considerably streamlined using online computational tools. The selection of appropriate epitopes for the vaccine construct was made by passing several immune filters, including antigenicity, allergenicity, and toxicity as per the earlier study [49]. The adequate epitopes for MHC-Class I and MHC-Class II were selected based on the highest VaxiJen score [22]. The epitopes for BCL were taken on passing set parameters for selection. Here, human β defensin (UniProt ID. Q5U7J2) was added as an adjuvant along with EAAAK peptide linker known to increase bifunctional catalytic activity, AAY peptide linker, KK, and GPGPG linkers which bring the pH level near the physiological range were used for constructing the vaccine sequence [54]. The adjuvant, linkers, and epitopes used for constructing the vaccine sequence were further analyzed on the set parameters and labeled stable for future use. The physicochemical characteristics of the designed vaccine were analyzed within the threshold value, making it an adequate vaccine candidate [50,55]. Further, tertiary structure prediction of the resultant vaccine sequence was performed, and the Ramachandran plot was constructed for validation of the derived structure, and the stereo-chemical quality of the vaccine was found to be good (Figure 3D). The engagement of vaccines with target immune receptors is crucial for generating a persistent immune response. Therefore, the binding mode and interactions of vaccine protein and TLR4 were investigated using molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation, as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5. The simulation study reveals the stability of the vaccine construct with the TLR4 receptor. Furthermore, the immunologic response of a vaccine protein was analyzed using In-silico simulations through the C-ImmSim server [44]. It shows the immune response after injecting by expressing different antibodies and stimulating a more robust immune response, as shown in Figure 6. Taken together, we propose a theoretical framework for the vaccine to combat JCPyV infections.

5. Conclusion

The JCV is a type of human polyomavirus that is a common cause of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a disease that affects the brain's white matter. PML is a rare but severe complication of immunosuppression, particularly in people with weakened immune systems due to other disease conditions such as HIV/AIDS or cancer. Currently, there is no vaccine available to prevent JC virus infection. The development of a vaccine against the JC virus is a complex challenge due to the virus's ability to persist in the human body without causing symptoms. A JCV-induced PML diagnosis in immunocompromised and transplant patients is often non-responsive to existing treatment, and more than 50% of patients with JCV-induced PML will die without any treatment. The prevalence of JCV and PML will increase in immunocompromised and transplant patients. Therefore, our multi-epitope vaccination may provide protection against the JCPyV, preventing viral replication and treating develop effective strategies for PML.

Limitation

This study further needs experimental validation, including the synthesis and in vitro and in vivo validations, to determine the immunogenicity. Antigenic variability is also a limitation. Many pathogens have the ability to rapidly evolve and change their epitopes, reducing the effectiveness of a multi-epitope vaccine.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

All authors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript, and there is no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Bajarang Kumbhar, Rajan Kumar Pandey, and Neetin S Desai; Methodology, Sukhada Kanse, Mehak Khandelwal and Bajarang Kumbhar; Formal analysis, Bajarang Kumbhar, Rajan Kumar Pandey, Manoj Khokhar and Neetin S Desai; Writing – original draft, Sukhada Kanse, Mehak Khandelwal and Bajarang Kumbhar; Writing – review & editing, Bajarang Kumbhar Rajan Kumar Pandey and Neetin S Desai; Visualization, Manoj Khokhar; Supervision, Bajarang Kumbhar.

Acknowledgments

BVK is thankful to NMIMS (Deemed to be) University, Mumbai for providing the computational facility. We are thankful to Biorender tool for providing imaging platform.

References

- Imperiale, M.J. JC Polyomavirus: Let's Please Respect Privacy. Journal of virology 2018, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, A.L.; Atwood, W.J. Fifty Years of JC Polyomavirus: A Brief Overview and Remaining Questions. Viruses 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shackelton, L.A.; Rambaut, A.; Pybus, O.G.; Holmes, E.C. JC virus evolution and its association with human populations. Journal of virology 2006, 80, 9928–9933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildreth, J.E.; Alcendor, D.J. JC polyomavirus and transplantation: implications for virus reactivation after immunosuppression in transplant patients and the occurrence of PML disease. Transplantology 2021, 2, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothpur, R.; Brennan, D.C. Human polyoma viruses and disease with emphasis on clinical BK and JC. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology 2010, 47, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalili, A.; Craigie, M.; Donadoni, M.; Sariyer, I.K. Host-Immune Interactions in JC Virus Reactivation and Development of Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML). Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology : the official journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology 2019, 14, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harypursat, V.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, S.; Chen, Y. JC Polyomavirus, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: a review. AIDS research and therapy 2020, 17, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C.D.; Derdowski, A.; Maginnis, M.S.; O'Hara, B.A.; Atwood, W.J. The VP1 subunit of JC polyomavirus recapitulates early events in viral trafficking and is a novel tool to study polyomavirus entry. Virology 2012, 428, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornikova, L.; Fraiberk, M.; Man, P.; Janovec, V.; Forstova, J. VP1, the major capsid protein of the mouse polyomavirus, binds microtubules, promotes their acetylation and blocks the host cell cycle. The FEBS journal 2017, 284, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayberry, C.L.; Nelson, C.D.S.; Maginnis, M.S. JC Polyomavirus Attachment and Entry: Potential Sites for PML Therapeutics. Current clinical microbiology reports 2017, 4, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neu, U.; Maginnis, M.S.; Palma, A.S.; Stroh, L.J.; Nelson, C.D.; Feizi, T.; Atwood, W.J.; Stehle, T. Structure-function analysis of the human JC polyomavirus establishes the LSTc pentasaccharide as a functional receptor motif. Cell host & microbe 2010, 8, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assetta, B.; Morris-Love, J.; Gee, G.V.; Atkinson, A.L.; O'Hara, B.A.; Maginnis, M.S.; Haley, S.A.; Atwood, W.J. Genetic and Functional Dissection of the Role of Individual 5-HT(2) Receptors as Entry Receptors for JC Polyomavirus. Cell reports 2019, 27, 1960–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietropaolo, V.; Prezioso, C.; Bagnato, F.; Antonelli, G. John Cunningham virus: an overview on biology and disease of the etiological agent of the progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. The new microbiologica 2018, 41, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- WHO, B. Listings of WHO’s response to COVID-19. World Health Organization 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, R.K.; Dahiya, S.; Mahita, J.; Sowdhamini, R.; Prajapati, V.K. Vaccination and immunization strategies to design Aedes aegypti salivary protein based subunit vaccine tackling Flavivirus infection. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 122, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, R.K.; Ojha, R.; Aathmanathan, V.S.; Krishnan, M.; Prajapati, V.K. Immunoinformatics approaches to design a novel multi-epitope subunit vaccine against HIV infection. Vaccine 2018, 36, 2262–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, R.K.; Ojha, R.; Dipti, K.; Kumar, R.; Prajapati, V.K. Immunoselective algorithm to devise multi-epitope subunit vaccine fighting against human cytomegalovirus infection. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2020, 82, 104282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, R.; Pareek, A.; Pandey, R.K.; Prusty, D.; Prajapati, V.K. Strategic Development of a Next-Generation Multi-Epitope Vaccine To Prevent Nipah Virus Zoonotic Infection. ACS omega 2019, 4, 13069–13079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lian, X.; Yan, L.; Pan, T.; Jin, T.; Xie, H.; Liang, Z.; Qiu, W.; et al. NPCDR: natural product-based drug combination and its disease-specific molecular regulation. Nucleic acids research 2022, 50, D1324–d1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UniProt, C. UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic acids research 2015, 43, D204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, E.; Hoogland, C.; Gattiker, A.; Duvaud, S.e.; Wilkins, M.R.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server; Springer: 2005.

- Doytchinova, I.A.; Flower, D.R. VaxiJen: a server for prediction of protective antigens, tumour antigens and subunit vaccines. BMC bioinformatics 2007, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Molecular biology and evolution 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vita, R.; Overton, J.A.; Greenbaum, J.A.; Ponomarenko, J.; Clark, J.D.; Cantrell, J.R.; Wheeler, D.K.; Gabbard, J.L.; Hix, D.; Sette, A.; et al. The immune epitope database (IEDB) 3.0. Nucleic acids research 2015, 43, D405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Kapoor, P.; Chaudhary, K.; Gautam, A.; Kumar, R.; Open Source Drug Discovery, C.; Raghava, G.P. In silico approach for predicting toxicity of peptides and proteins. PloS one 2013, 8, e73957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrov, I.; Naneva, L.; Doytchinova, I.; Bangov, I. AllergenFP: allergenicity prediction by descriptor fingerprints. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundegaard, C.; Lamberth, K.; Harndahl, M.; Buus, S.; Lund, O.; Nielsen, M. NetMHC-3.0: accurate web accessible predictions of human, mouse and monkey MHC class I affinities for peptides of length 8-11. Nucleic acids research 2008, 36, W509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, I.; Flower, D.R.; Doytchinova, I. AllerTOP--a server for in silico prediction of allergens. BMC bioinformatics 2013, 14 Suppl 6, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, S.S.; Singh, P.; Kashyap, P.; Sansi, M.S.; Ali, S.A. Promising role of defensins peptides as therapeutics to combat against viral infection. Microbial pathogenesis 2021, 155, 104930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durr, U.H.; Sudheendra, U.S.; Ramamoorthy, A. LL-37, the only human member of the cathelicidin family of antimicrobial peptides. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2006, 1758, 1408–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, A.; Zenobia, C.; Darveau, R.P. Defensins and LL-37: a review of function in the gingival epithelium. Periodontology 2000 2013, 63, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Park, H.; Heo, L.; Seok, C. GalaxyWEB server for protein structure prediction and refinement. Nucleic acids research 2012, 40, W294–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laskowski, R.; MacArthur, M.; Moss, D.; Thornton, J. IUCr. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. urn: issn, 8898. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmich, N.N.; Sivak, K.V.; Chubarev, V.N.; Porozov, Y.B.; Savateeva-Lyubimova, T.N.; Peri, F. TLR4 signaling pathway modulators as potential therapeutics in inflammation and sepsis. Vaccines 2017, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboudounya, M.M.; Heads, R.J. COVID-19 and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4): SARS-CoV-2 may bind and activate TLR4 to increase ACE2 expression, facilitating entry and causing hyperinflammation. Mediators of inflammation 2021, 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janovec, V.; Ryabchenko, B.; Skarkova, A.; Pokorna, K.; Rosel, D.; Brabek, J.; Weber, J.; Forstova, J.; Hirsch, I.; Huerfano, S. TLR4-Mediated Recognition of Mouse Polyomavirus Promotes Cancer-Associated Fibroblast-Like Phenotype and Cell Invasiveness. Cancers 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneidman-Duhovny, D.; Inbar, Y.; Nussinov, R.; Wolfson, H.J. PatchDock and SymmDock: servers for rigid and symmetric docking. Nucleic acids research 2005, 33, W363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashiach, E.; Schneidman-Duhovny, D.; Andrusier, N.; Nussinov, R.; Wolfson, H.J. FireDock: a web server for fast interaction refinement in molecular docking. Nucleic acids research 2008, 36, W229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. Journal of computational chemistry 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbhar, B.V.; Bhandare, V.V.; Panda, D.; Kunwar, A. Delineating the interaction of combretastatin A-4 with alphabeta tubulin isotypes present in drug resistant human lung carcinoma using a molecular modeling approach. Journal of biomolecular structure & dynamics 2020, 38, 426–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N⋅ log (N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. The Journal of chemical physics 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R. Pá ll S, Smith JC, Hess B, et al. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015; 1–2: 19–25.

- DeLano, W.L. Pymol: An open-source molecular graphics tool. CCP4 Newsl. Protein Crystallogr 2002, 40, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rapin, N.; Lund, O.; Castiglione, F. Immune system simulation online. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2013–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaleeckal Mathew, O.; Sowdhamini, R. PIMA: Protein-Protein interactions in Macromolecular Assembly - a web server for its Analysis and Visualization. Bioinformation 2016, 12, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollebo, H.S.; White, M.K.; Gordon, J.; Berger, J.R.; Khalili, K. Persistence and pathogenesis of the neurotropic polyomavirus JC. Annals of neurology 2015, 77, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauver, M.D.; Lukacher, A.E. JCPyV VP1 Mutations in Progressive MultifocalLeukoencephalopathy: Altering Tropismor Mediating Immune Evasion? Viruses 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajighahramani, N.; Nezafat, N.; Eslami, M.; Negahdaripour, M.; Rahmatabadi, S.S.; Ghasemi, Y. Immunoinformatics analysis and in silico designing of a novel multi-epitope peptide vaccine against Staphylococcus aureus. Infection, genetics and evolution : journal of molecular epidemiology and evolutionary genetics in infectious diseases 2017, 48, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, R.K.; Ojha, R.; Mishra, A.; Kumar Prajapati, V. Designing B- and T-cell multi-epitope based subunit vaccine using immunoinformatics approach to control Zika virus infection. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2018, 119, 7631–7642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Kumari, V.; Kumbhar, B.V.; Mukherjee, A.; Pandey, R.; Kondabagil, K. Immunoinformatics approach for a novel multi-epitope subunit vaccine design against various subtypes of Influenza A virus. Immunobiology 2021, 226, 152053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyster, J.G.; Allen, C.D.C. B Cell Responses: Cell Interaction Dynamics and Decisions. Cell 2019, 177, 524–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, M.C.; Mahajan, S.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M.; Marcatili, P. Antibody Specific B-Cell Epitope Predictions: Leveraging Information From Antibody-Antigen Protein Complexes. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Multi-epitope vaccines: a promising strategy against tumors and viral infections. Cellular & molecular immunology 2018, 15, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Asif Rasheed, M.; Raza, S.; Tariq Navid, M.; Afzal, A.; Jamil, F. Prediction and analysis of multi epitope based vaccine against Newcastle disease virus based on haemagglutinin neuraminidase protein. Saudi journal of biological sciences 2022, 29, 3006–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, V.; Rungta, T.; Goyal, K.; Singh, M.P. Designing a multi-epitope based vaccine to combat Kaposi Sarcoma utilizing immunoinformatics approach. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Transmission of JC Polyomavirus. Here, steps 1, 2, 3, and 4 demonstrate how primary viremia is caused by virions entering the body through the tonsil epithelium, upper respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal system (mainly archetypal and infrequently neurotropic type). Steps 5, 6, and 7 demonstrate how viremia affects the kidney and other organs. JCV replication takes place in the kidney, and the JCV life cycle is finished by viruria caused by shedding from the apical face. Through bone marrow, JCV enters the brain hematogenously together with leukocytes. PML is indicated by the development of brain microlesions [4] (created using Biorender.com).

Figure 1.

Transmission of JC Polyomavirus. Here, steps 1, 2, 3, and 4 demonstrate how primary viremia is caused by virions entering the body through the tonsil epithelium, upper respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal system (mainly archetypal and infrequently neurotropic type). Steps 5, 6, and 7 demonstrate how viremia affects the kidney and other organs. JCV replication takes place in the kidney, and the JCV life cycle is finished by viruria caused by shedding from the apical face. Through bone marrow, JCV enters the brain hematogenously together with leukocytes. PML is indicated by the development of brain microlesions [4] (created using Biorender.com).

Figure 2.

Structure of JC Polyomavirus. Here, (A) JC Polyomavirus is shown schematically, and (B) the primary capsid protein of JC Polyomavirus is shown in three dimensions view using 3NXG.pdb from www.rcsb.org, The primary capsid protein VP1, which makes up 72 pentamers in the JC virus capsid, is present alongside lesser capsid proteins VP2 and VP3; (C) Phylogenetic analysis of VP1 major coat protein of JC polyomavirus. The rate of diversification is lower in VP1.

Figure 2.

Structure of JC Polyomavirus. Here, (A) JC Polyomavirus is shown schematically, and (B) the primary capsid protein of JC Polyomavirus is shown in three dimensions view using 3NXG.pdb from www.rcsb.org, The primary capsid protein VP1, which makes up 72 pentamers in the JC virus capsid, is present alongside lesser capsid proteins VP2 and VP3; (C) Phylogenetic analysis of VP1 major coat protein of JC polyomavirus. The rate of diversification is lower in VP1.

Figure 3.

Structure of vaccine construct. Here, (A) Schematic representation of the linear vaccine construct shows the linear vaccine construct with CTL, HTL, and B-Cell depicted in sea green, pink and green boxes, respectively. EAAAK linker (yellow) was used for linking the adjuvant, and GPGPG linkers (green) were used for linking the epitopes. The linker design consists of Human β defensin 3 –EAAAK- LL-3 –EAAAK- Class 2 epitopes (GPGPG)-MHC Class 1 epitope (AAY)- B cell epitopes-KK- HHHHHH; (B) shows the three-dimensional structure of the vaccine construct, (C) with hydrophobic surface area, and (D) Stereochemical quality of the vaccine construct using Ramachandran plot.

Figure 3.

Structure of vaccine construct. Here, (A) Schematic representation of the linear vaccine construct shows the linear vaccine construct with CTL, HTL, and B-Cell depicted in sea green, pink and green boxes, respectively. EAAAK linker (yellow) was used for linking the adjuvant, and GPGPG linkers (green) were used for linking the epitopes. The linker design consists of Human β defensin 3 –EAAAK- LL-3 –EAAAK- Class 2 epitopes (GPGPG)-MHC Class 1 epitope (AAY)- B cell epitopes-KK- HHHHHH; (B) shows the three-dimensional structure of the vaccine construct, (C) with hydrophobic surface area, and (D) Stereochemical quality of the vaccine construct using Ramachandran plot.

Figure 4.

Molecular docking of vaccine with TLR4. Here, (A) Shows the docked complex of vaccine construct (orange) with Toll-Like Receptor 4 (Chain A; cyan and Chain B; yellow) using molecular docking; (B) Interaction network of vaccine construct with chain A and B of TLR4; hydrogen bonding interactions are shown in blue, Non-bonded interactions are shown in orange, salt bridge shown in orange.

Figure 4.

Molecular docking of vaccine with TLR4. Here, (A) Shows the docked complex of vaccine construct (orange) with Toll-Like Receptor 4 (Chain A; cyan and Chain B; yellow) using molecular docking; (B) Interaction network of vaccine construct with chain A and B of TLR4; hydrogen bonding interactions are shown in blue, Non-bonded interactions are shown in orange, salt bridge shown in orange.

Figure 5.

Analysis of molecular dynamics simulation of TLR4-vaccine complex. Here, (A) show the RMSD of the TLR4-vaccine complex for 100ns, RMSD revealed that the vaccine and TLR4 receptor forms a stable complex. Similarly, (B) shows the radius of the gyration plot reveals that the complex is stable. (C) shows the RMSF of the vaccine, and (D) shows the RMSF of TLR4 receptor chain A (black) and B (red) for 100 ns time steps.

Figure 5.

Analysis of molecular dynamics simulation of TLR4-vaccine complex. Here, (A) show the RMSD of the TLR4-vaccine complex for 100ns, RMSD revealed that the vaccine and TLR4 receptor forms a stable complex. Similarly, (B) shows the radius of the gyration plot reveals that the complex is stable. (C) shows the RMSF of the vaccine, and (D) shows the RMSF of TLR4 receptor chain A (black) and B (red) for 100 ns time steps.

Figure 6.

Shows the C-ImmSim is an in silico immune simulation against VP1 vaccine protein as antigen. Simulations are presented after the next three injections at steps 1, 84, and 168. Here, (A) shows the antigen and immunoglobins, (B) shows the cytokine production. (C) Show the TH cell population, and (D) show the B cell population.

Figure 6.

Shows the C-ImmSim is an in silico immune simulation against VP1 vaccine protein as antigen. Simulations are presented after the next three injections at steps 1, 84, and 168. Here, (A) shows the antigen and immunoglobins, (B) shows the cytokine production. (C) Show the TH cell population, and (D) show the B cell population.

Table 1.

List of selected B cell epitopes.

| Peptide | Length | Antigenicity | Allergenicity | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WEAVTLKTEVIGVT | 14 | Antigenic | Non-Allergen | Non-Toxin |

| NPYPISFLLTD | 11 | Antigenic | Non-Allergen | Non-Toxic |

Table 2.

List of selected HTL cell epitopes.

| Peptide | Length | Antigenicity | Allergenicity | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENVPPVLHINTATT | 15 | Antigenic | Non-Allergen | Non-Toxin |

| KRRVKNPYISFLLT | 15 | Antigenic | Non-Allergen | Non-Toxin |

| LRKRRVKNPYISFL | 15 | Antigenic | Non-Allergen | Non-Toxin |

|

FGVGPLCKGDNLYLS |

15 | Antigenic | Non-Allergen | Non-Toxin |

|

GGEALELQGVLFNYR |

15 | Antigenic | Non-Allergen | Non-Toxin |

Table 3.

List of selected CTL cell epitopes.

| Peptide | Length | Antigenicity | Allergenicity | Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGMFTKRSG | 9 | Antigenic | Non-Allergen | Non-Toxin |

| DLTCGNILM | 9 | Antigenic | Non-Allergen | Non-Toxin |

| ELQGVVFNYR | 10 | Antigenic | Non-Allergen | Non-Toxin |

| GVEVLEVKTG | 10 | Antigenic | Non-Allergen | Non-Toxin |

| GVVFNYRTK | 9 | Antigenic | Non-Allergen | Non-Toxin |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Copyright: This open access article is published under a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, which permit the free download, distribution, and reuse, provided that the author and preprint are cited in any reuse.

Downloads

192

Views

71

Comments

0

Subscription

Notify me about updates to this article or when a peer-reviewed version is published.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2025 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated