Submitted:

28 April 2023

Posted:

28 April 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The motion elements necessary for animacy perception and emotional expressions are revealed by having participants design the movements.

- The motion elements identified in the simulator experiment are revealed whether sufficient to express emotions with animacy by having other participants observe movements.

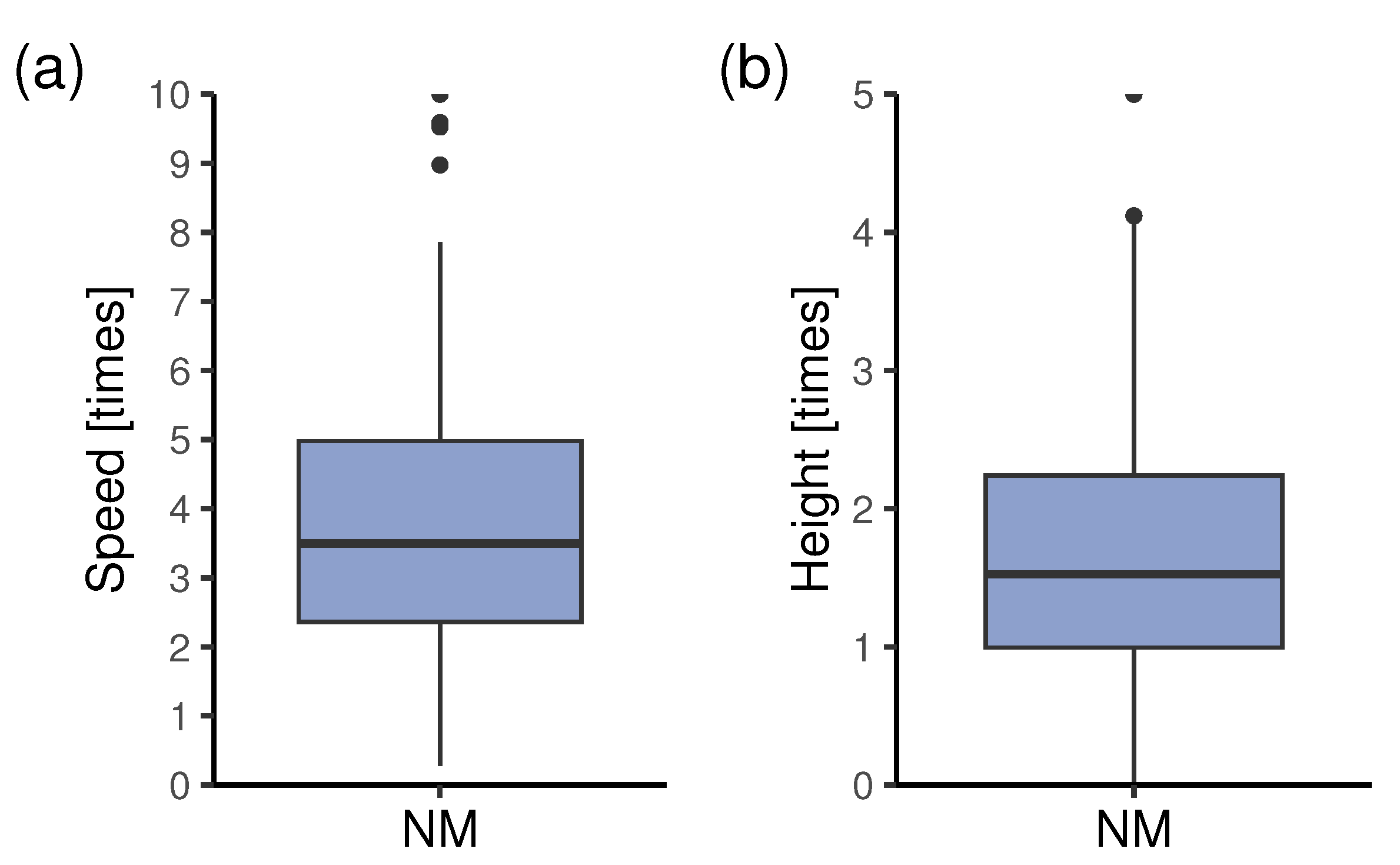

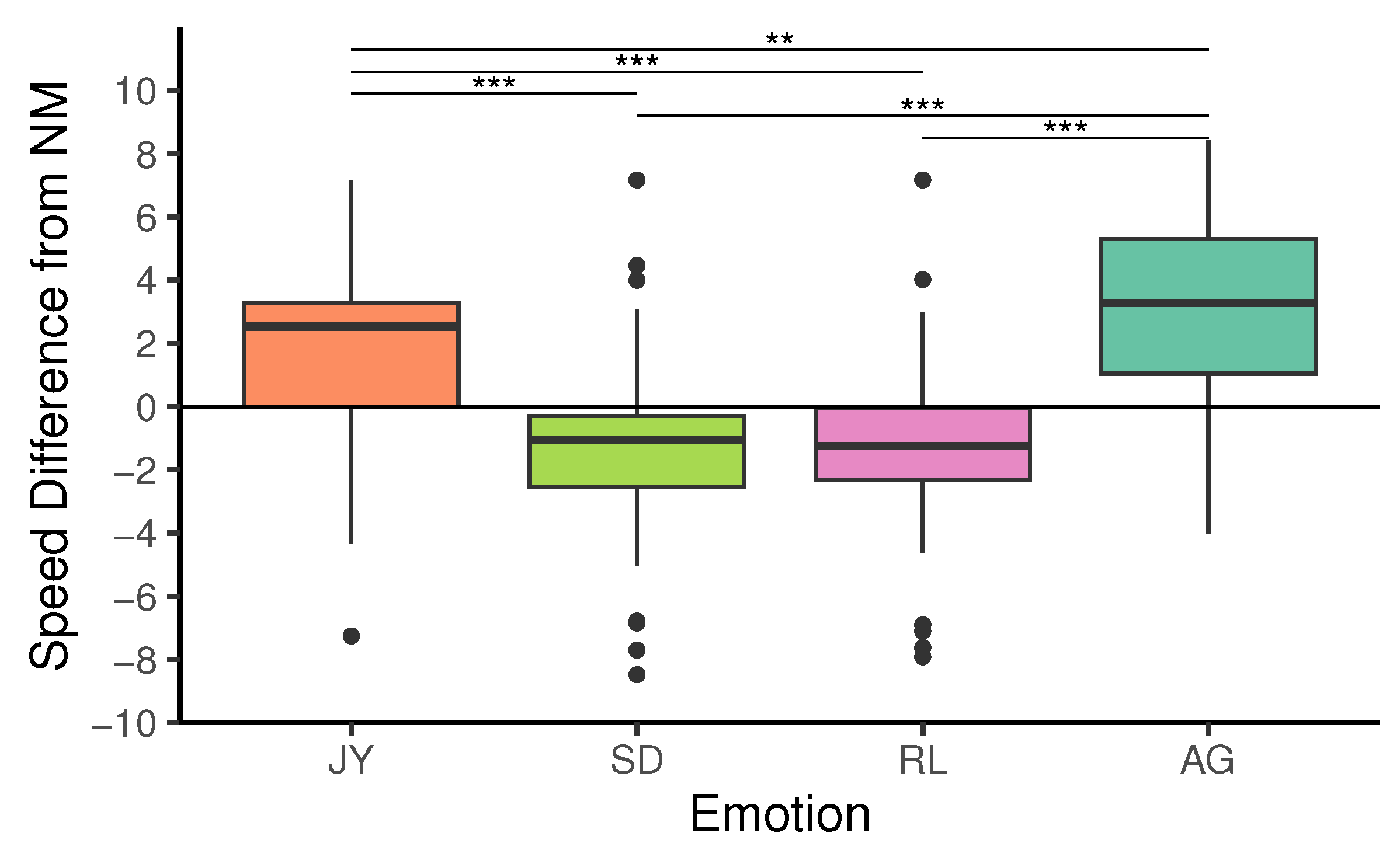

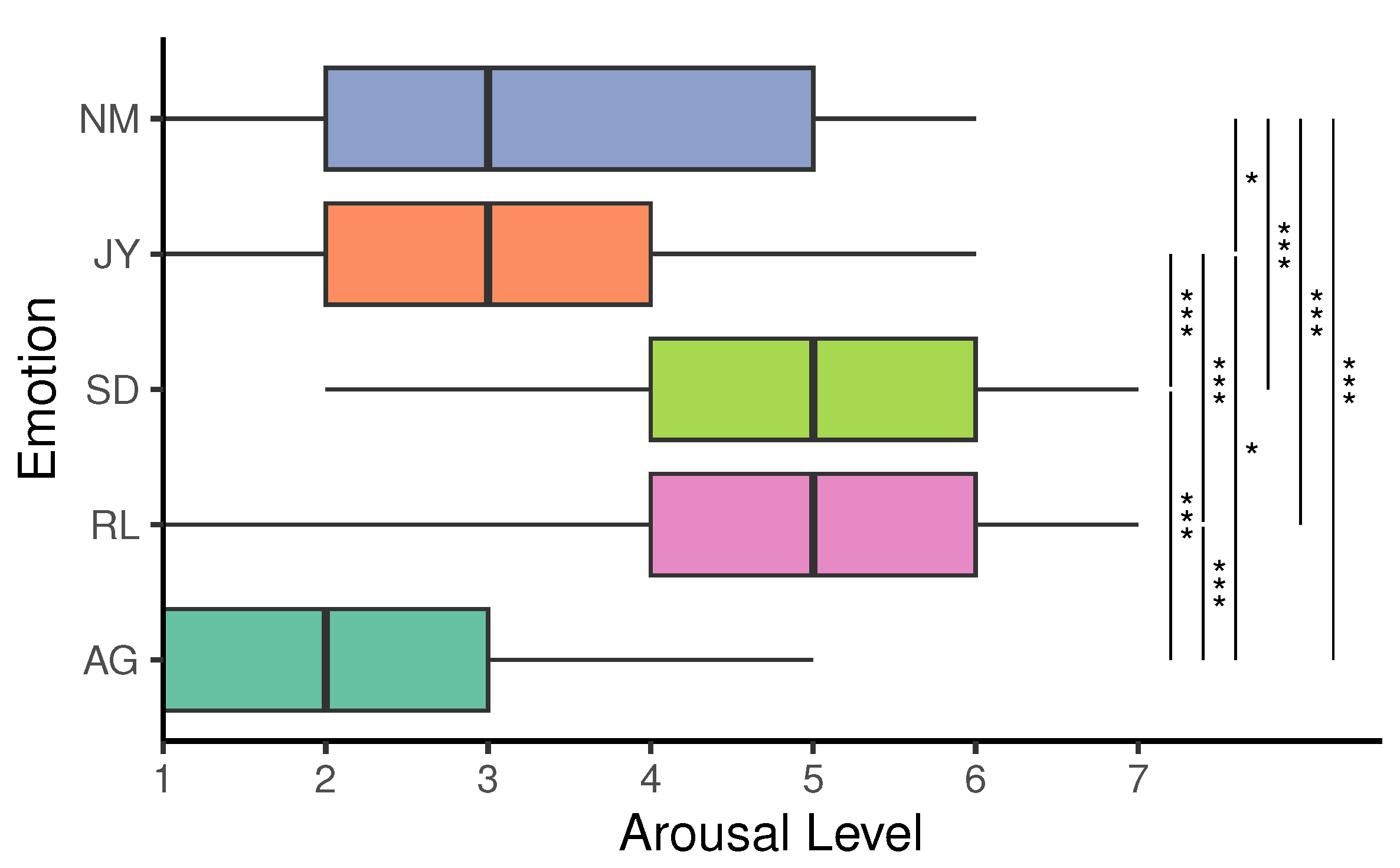

- Through the two experiments, we showed that the median of speed required for animacy was , the median of height was at the edges/ at the center, the difference in each of these values was mainly related to emotional expression, and it was possible to express high and low arousal levels with these elements.

2. Related Work

2.1. Animacy perception

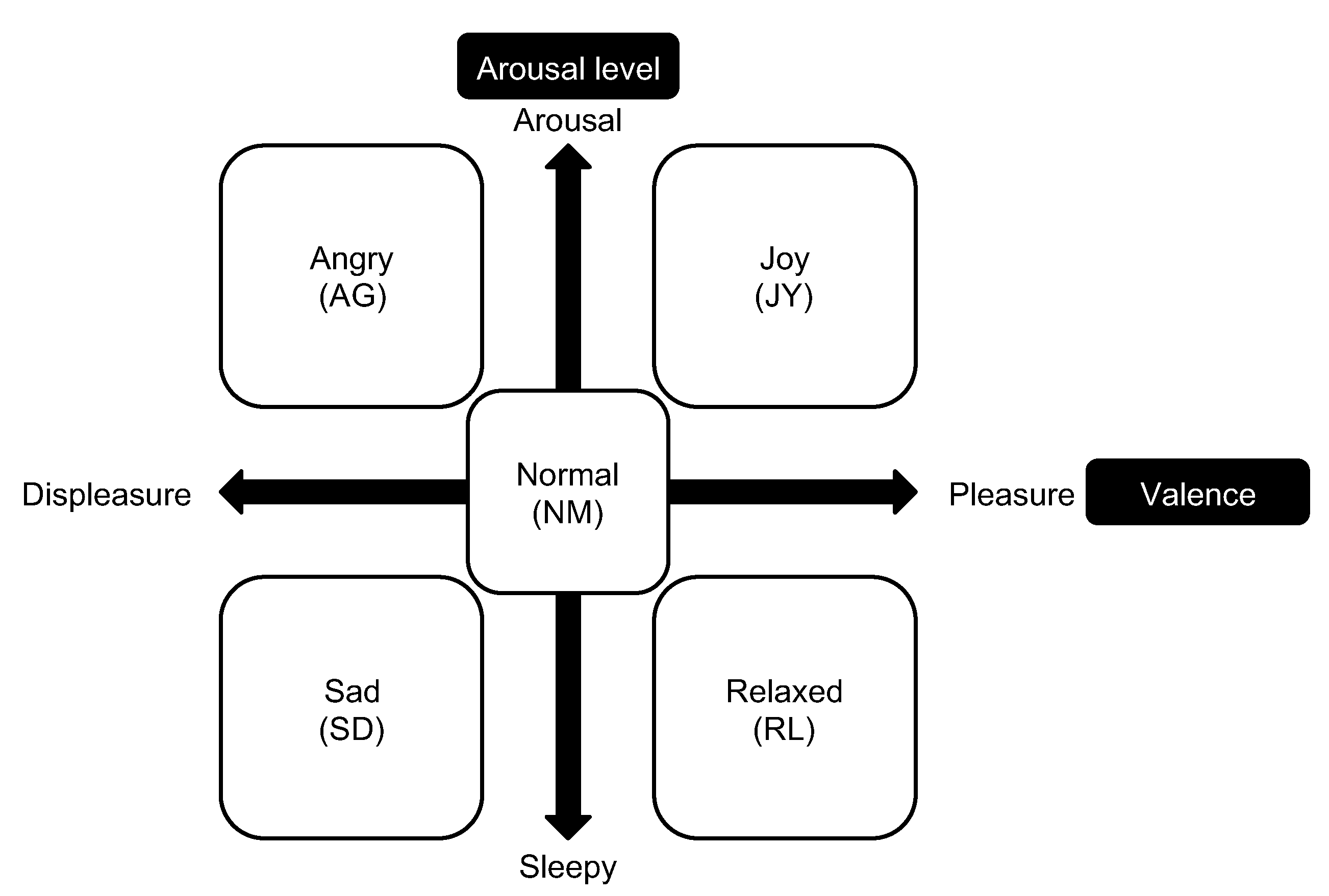

2.2. Emotional expression

3. Experiment 1: Motion Elements for Animacy Perception and Emotional Expressions

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Our approach

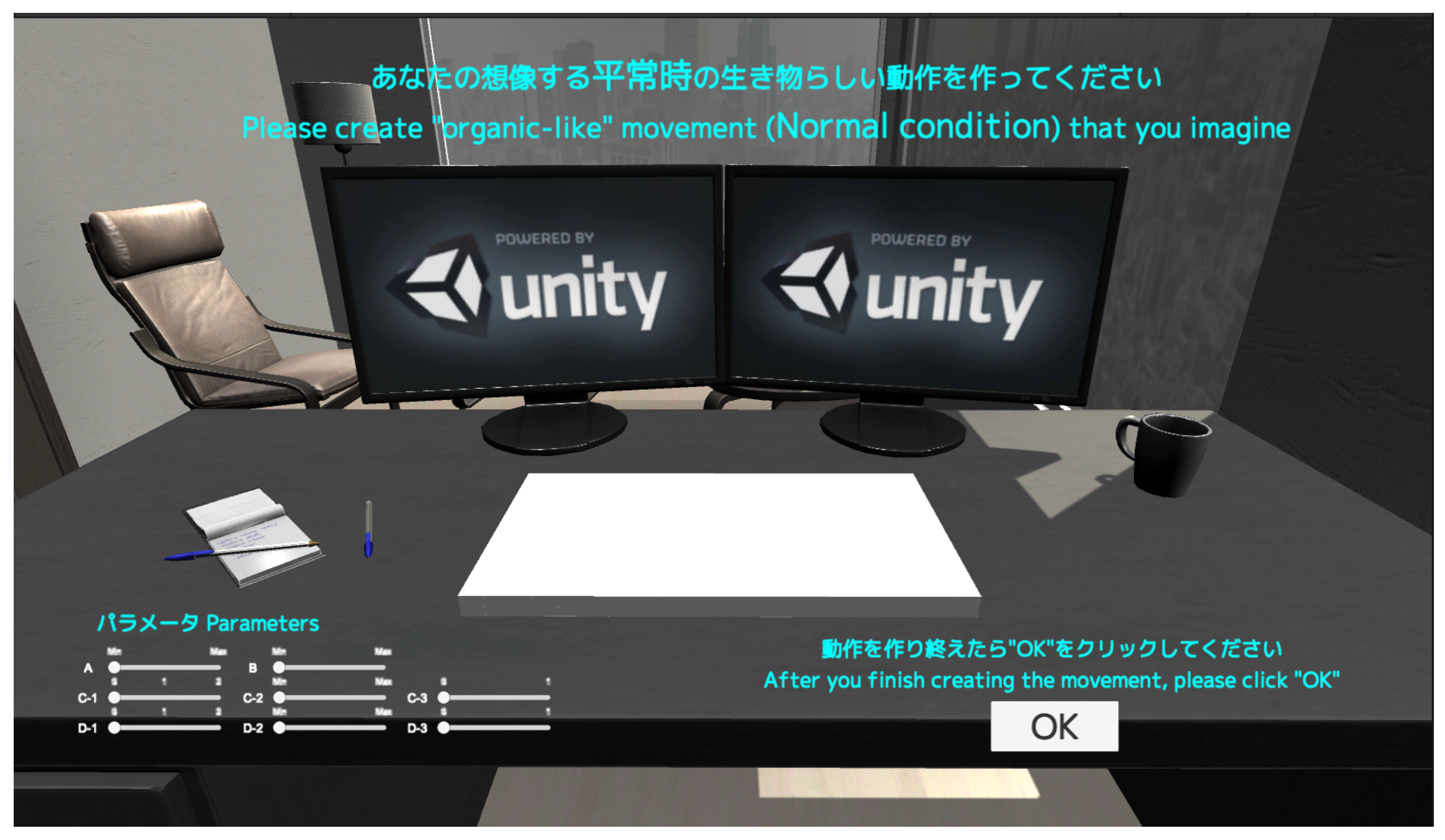

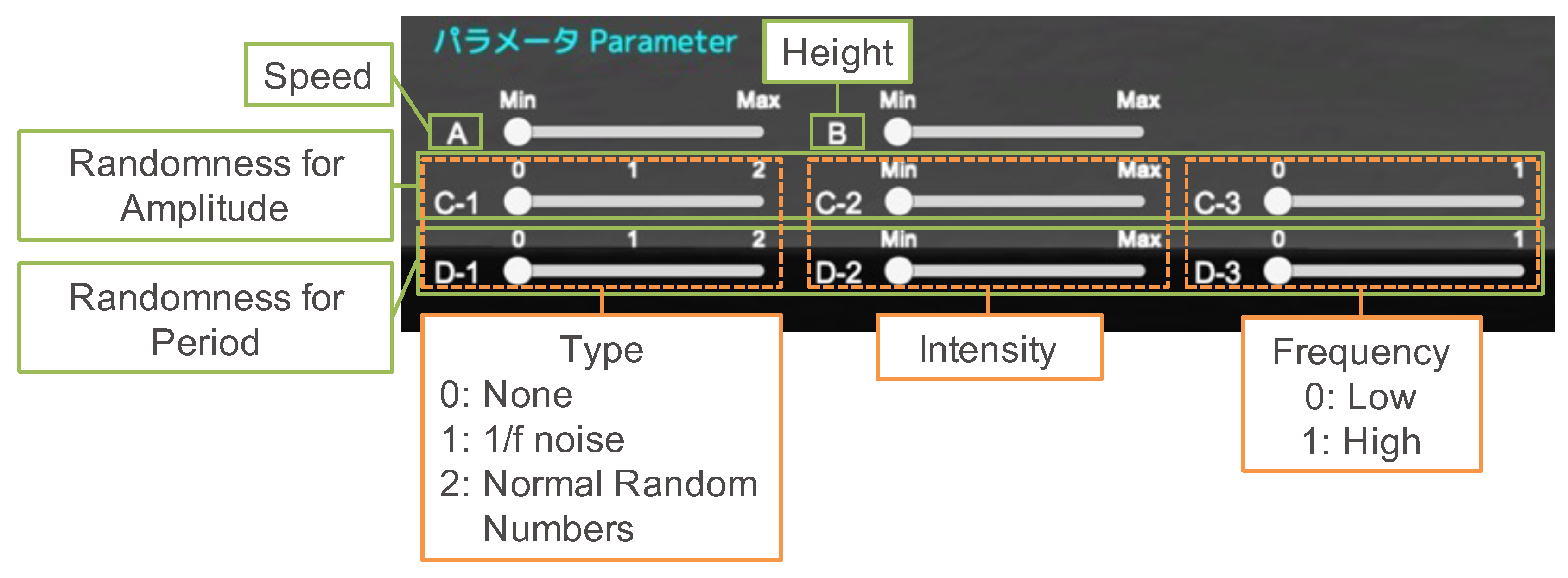

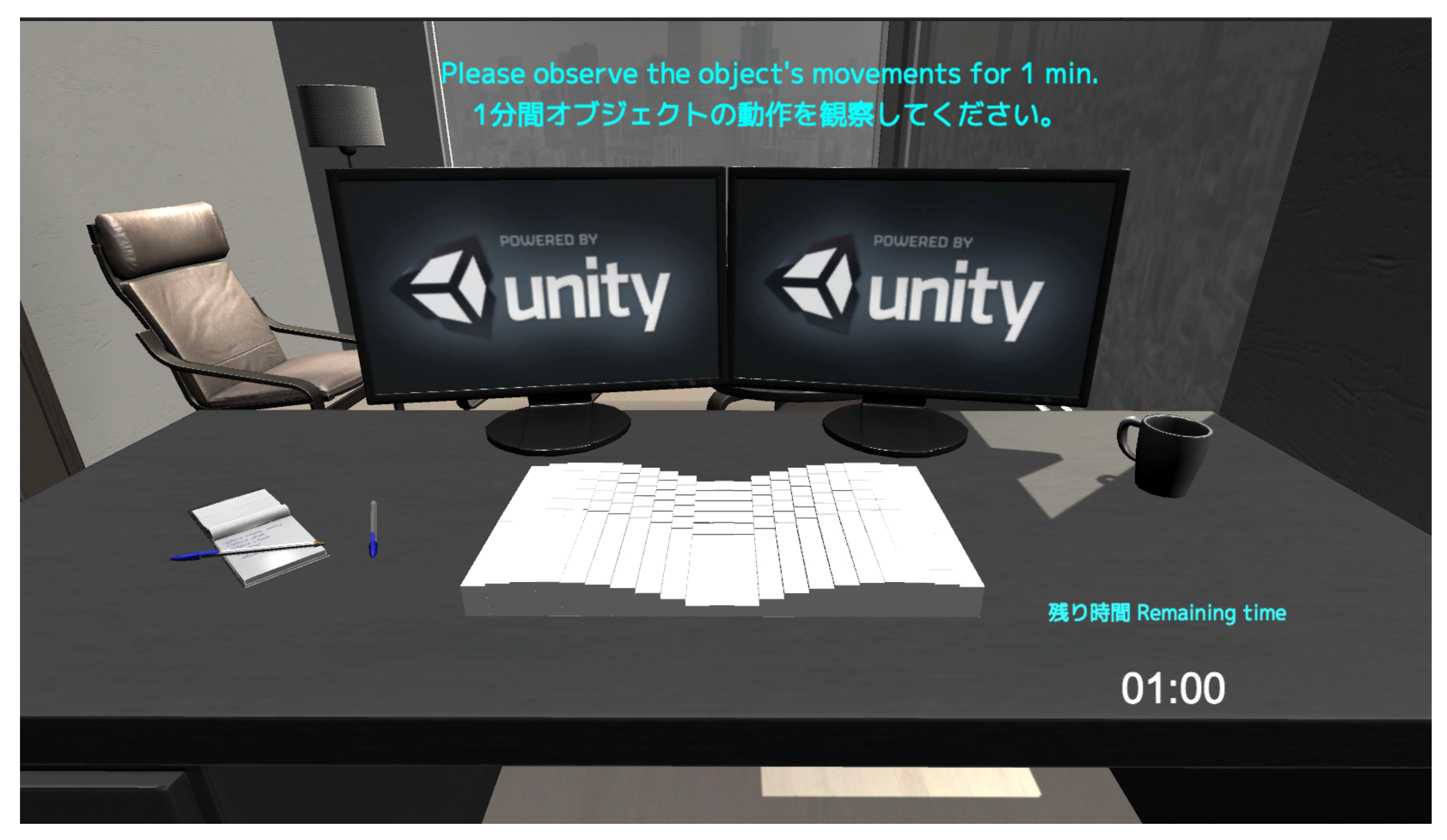

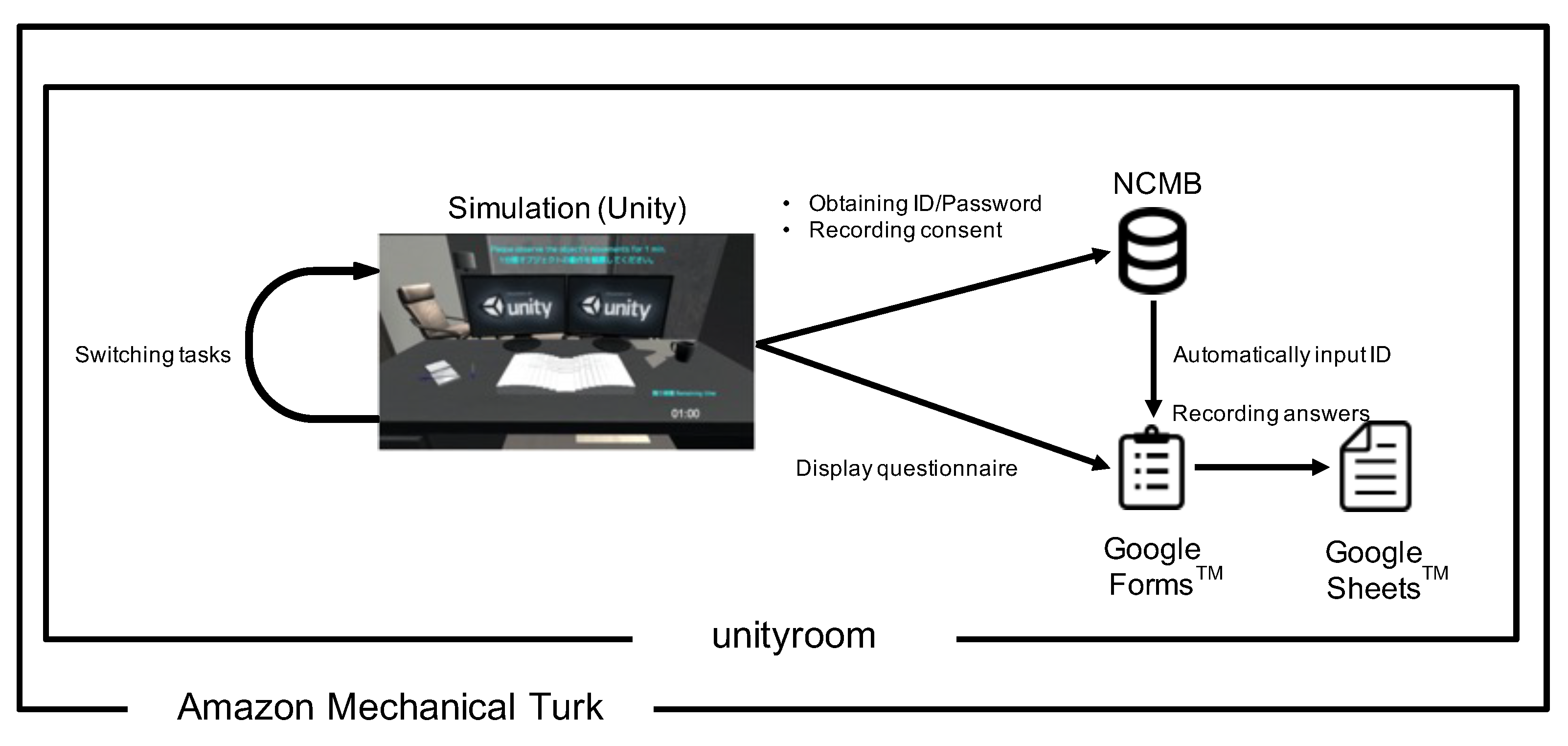

3.1.2. Simulator implementation

| Algorithm 1: Calculate 1/f noise |

|

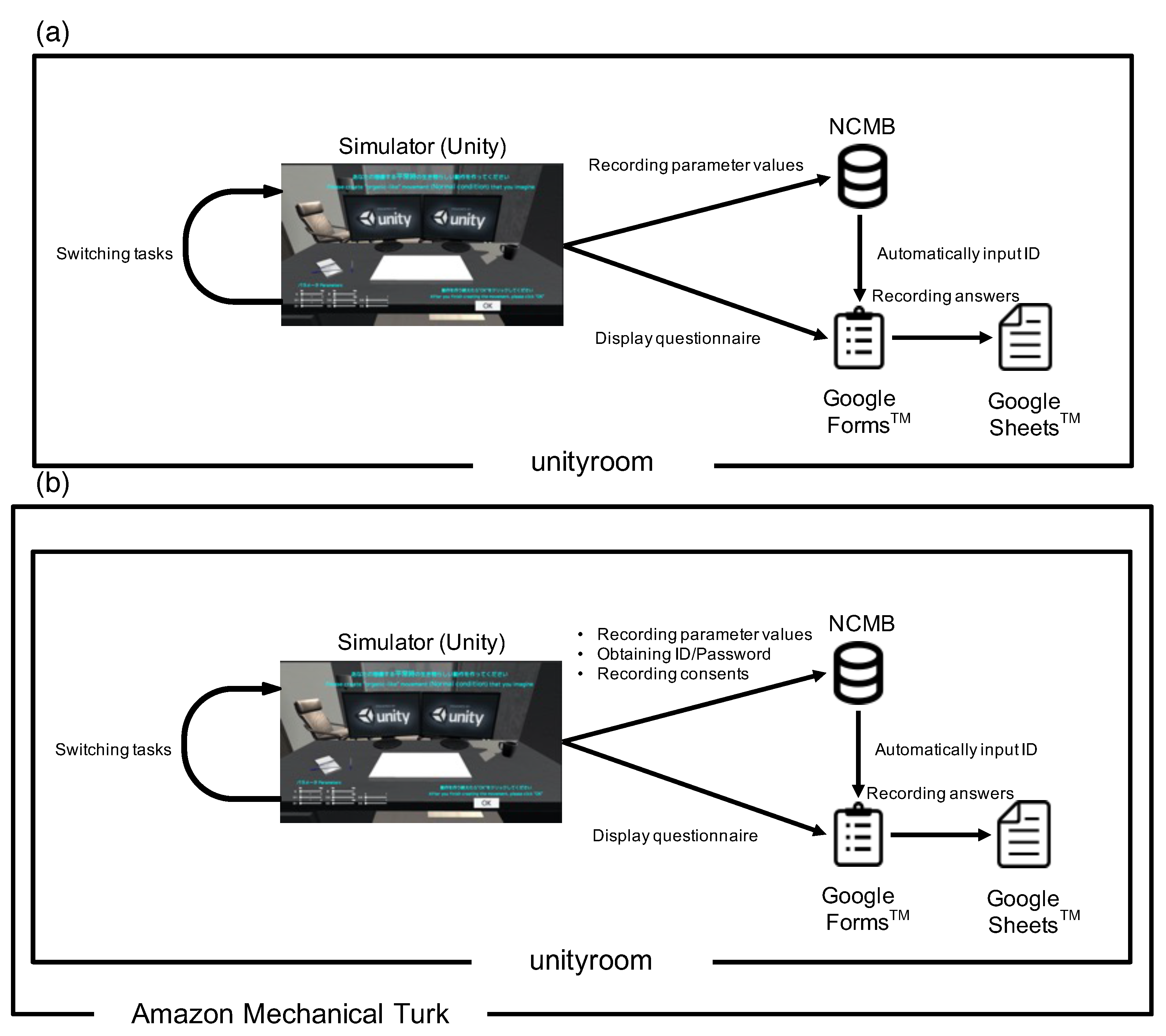

3.1.3. Experimental setup

3.1.4. Procedure

- Read the experiment instruction and responded to the consent form.

- Read through the operation manual of the system.

- Practiced the simulator operation for three minutes.

- Executed each task.

- Answered questionnaire about motions in each task.

- Repeated steps 3 to 4.

- Task 1

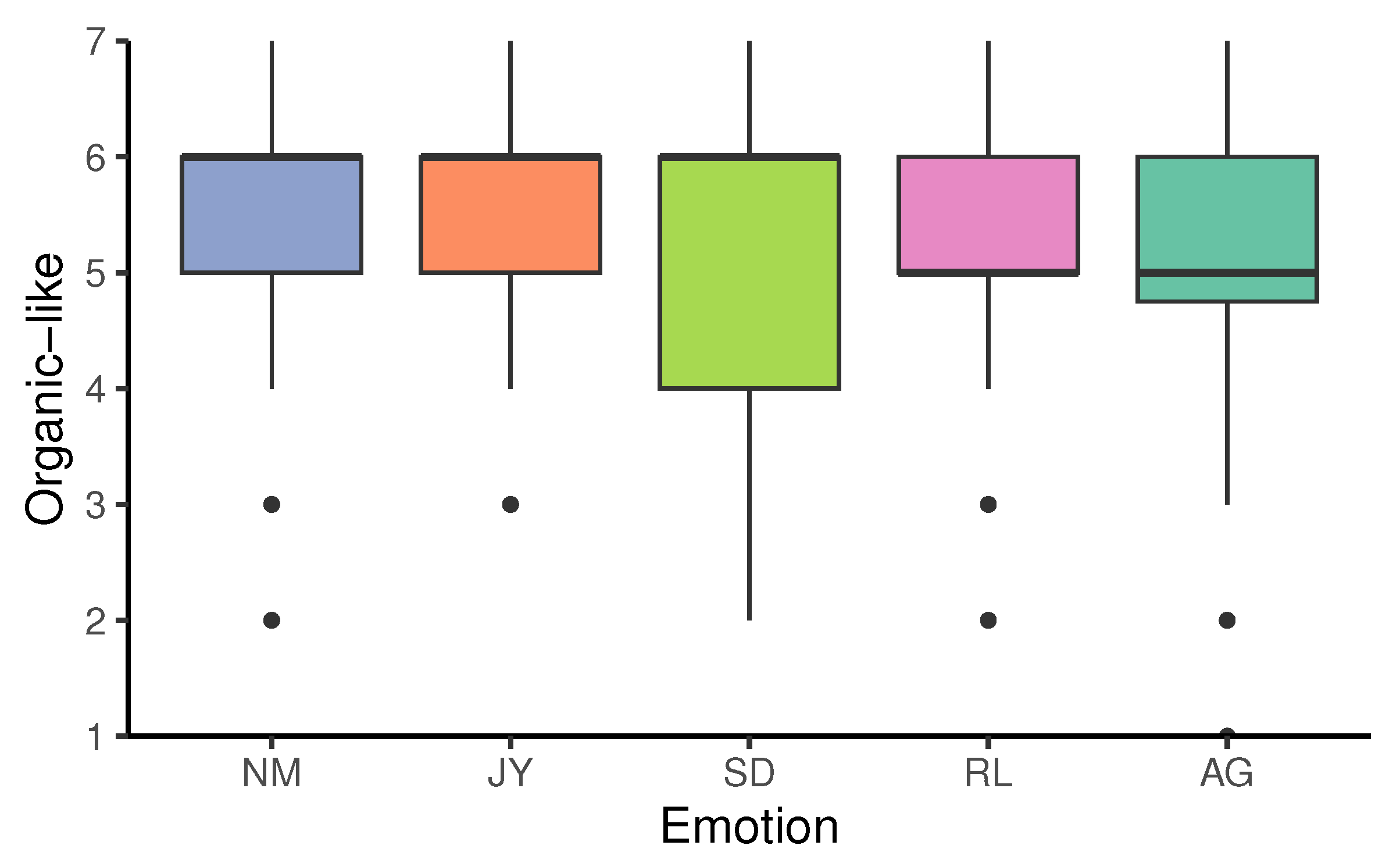

- To create “organic-like” motion expressing “Normal (NM)” state

- Task 2

- To create “organic-like” motion expressing “Joy (JY)” state

- Taks 3

- To create “organic-like” motion expressing “Sad (SD)” state

- Task 4

- To create “organic-like” motion expressing “Relaxed (RL)” state

- Task 5

- To create “organic-like” motion expressing “Angry (AG)” state

3.1.5. Participants

3.2. Results

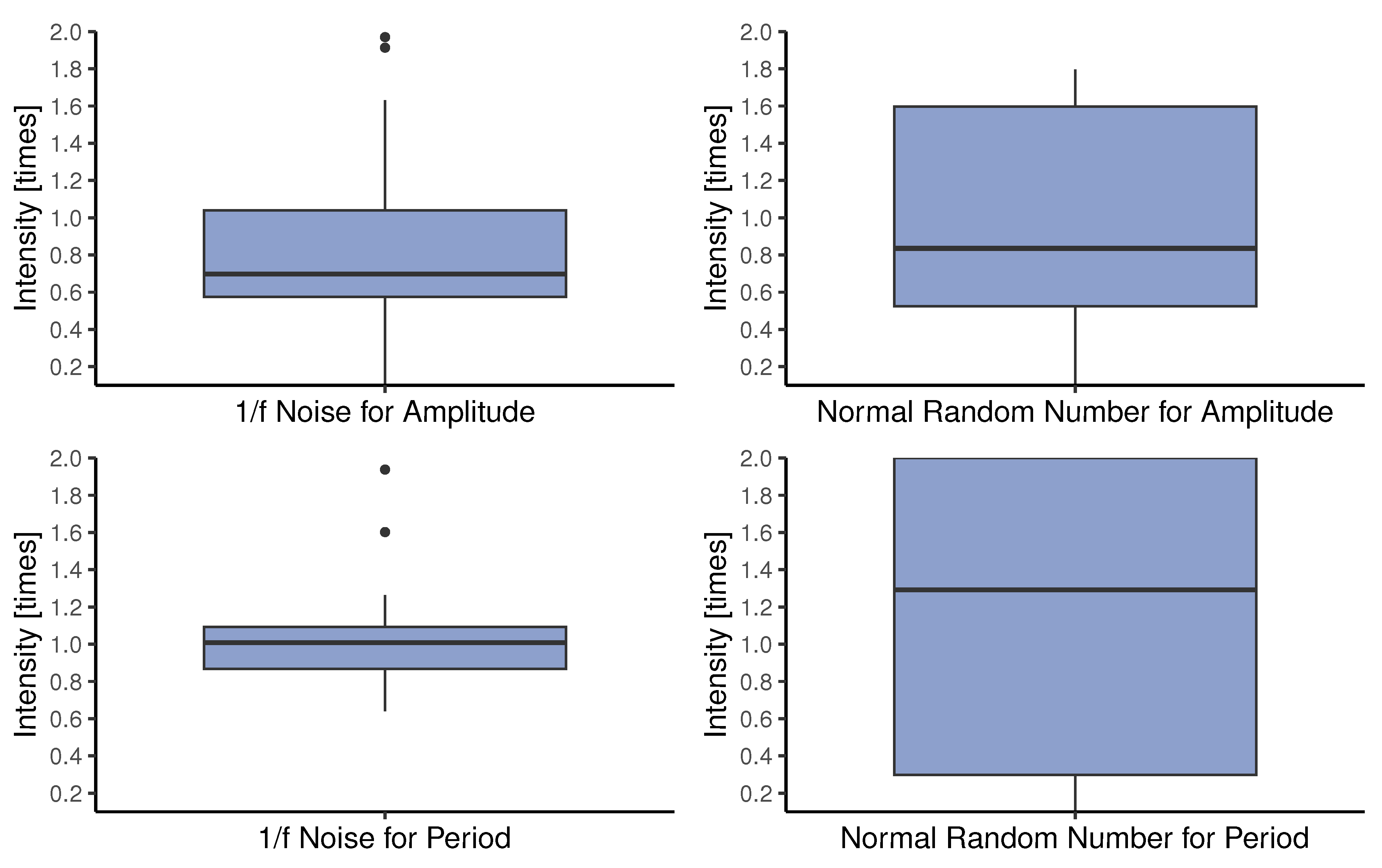

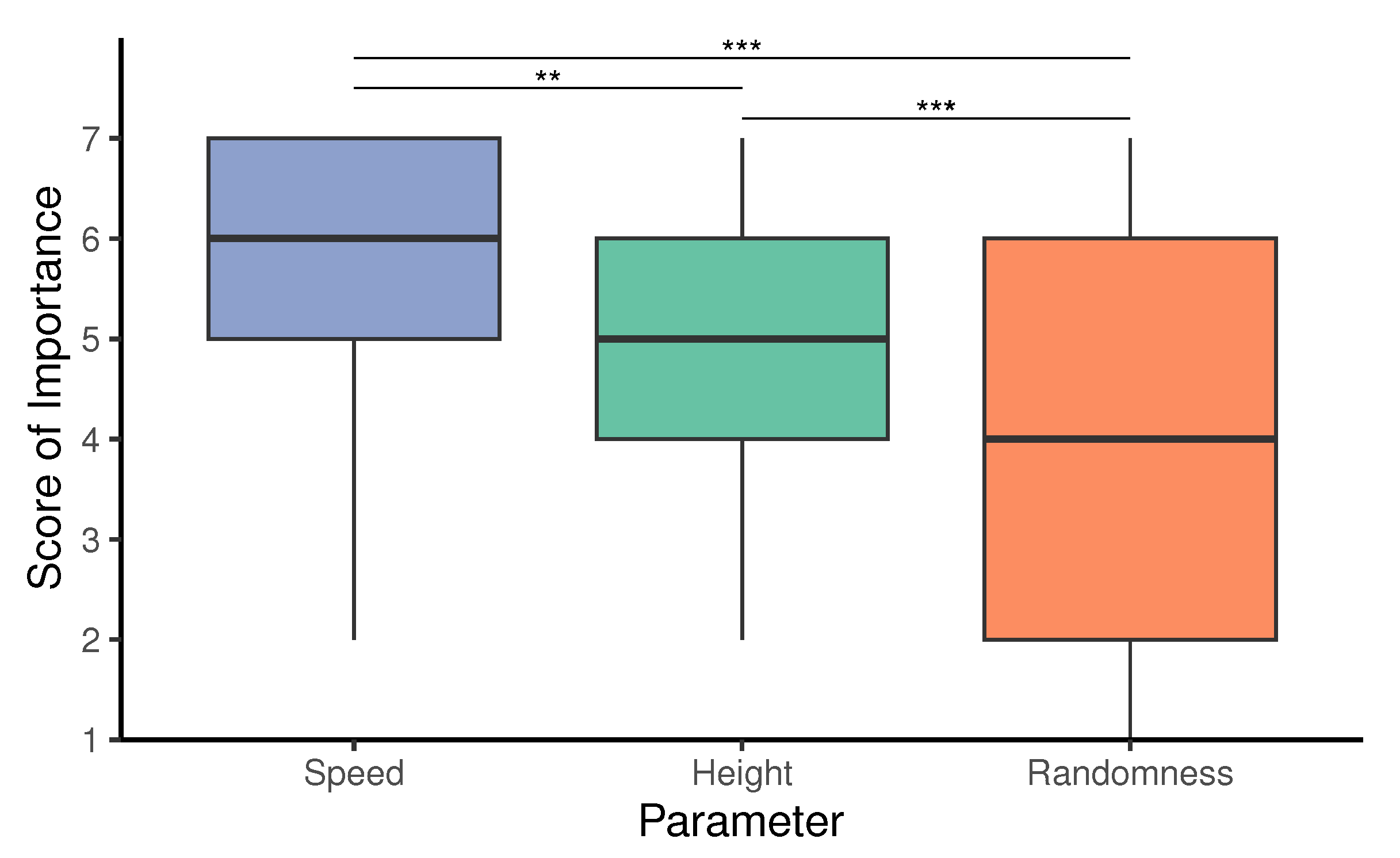

3.2.1. Motion elements for animacy perception

3.2.2. Motion elements for expressing emotions

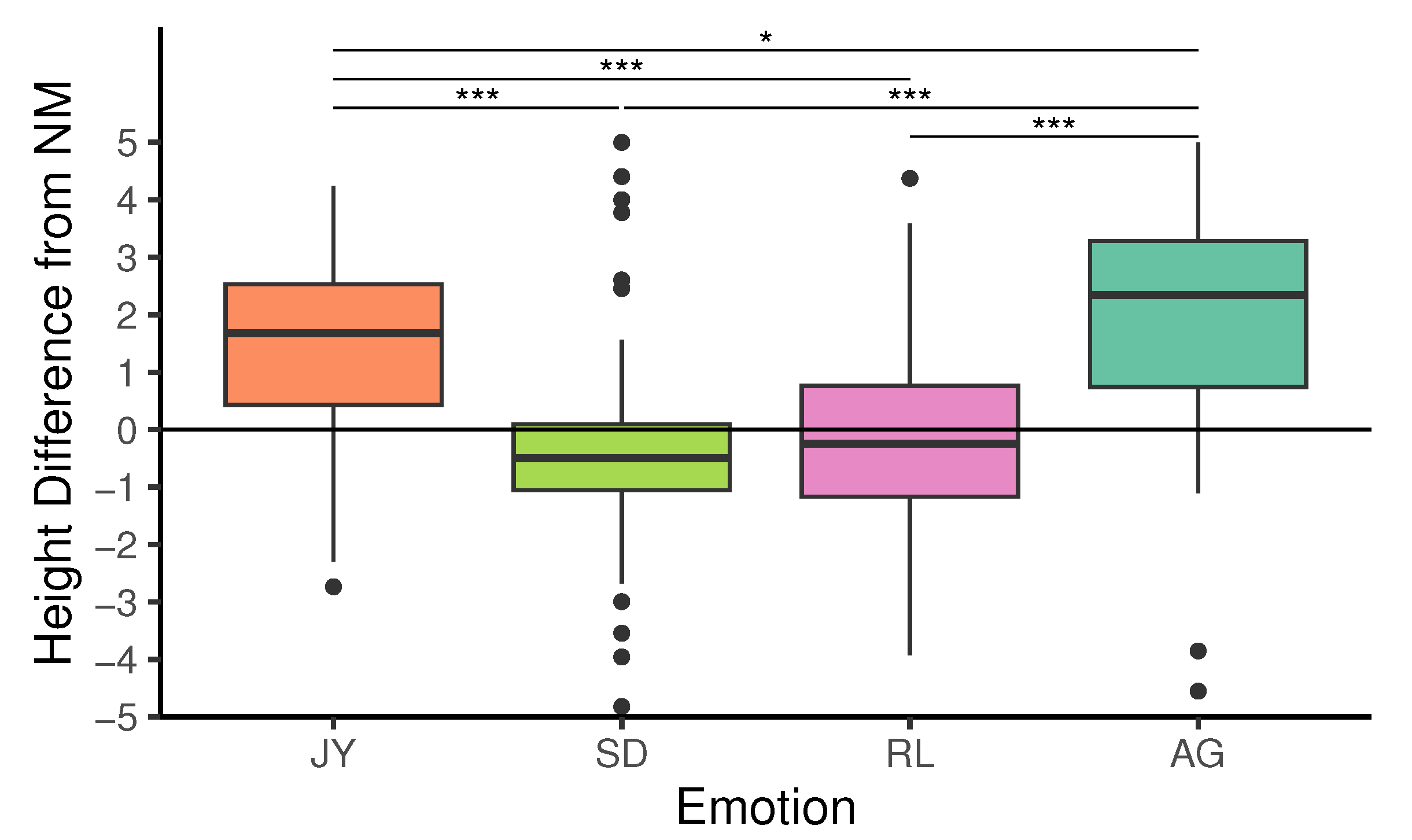

3.2.3. Motion expressing emotions with animacy

4. Experiment 2: Emotion Understanding from Representative Motion Elements

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. Our approach

4.1.2. Simulator implementation

4.1.3. Experimental setup

4.1.4. Procedure

- Read the experiment instruction and responded to the consent form.

- Read through the operation manual of the system.

- Answered the pre-questionnaire.

- Executed each task. Observed the simulator for 1 minute per each task.

- Answered the questionnaire about motions in each task.

- Repeated steps 4 to 5.

- Answered the final questionnaire.

- Task 1

- To observe the “organic-like” motion expressing “Normal (NM)” state

- Task 2

- To observe the “organic-like” motion expressing “Joy (JY)” state

- Task 3

- To observe the “organic-like” motion expressing “Sad (SD)” state

- Task 4

- To observe the “organic-like” motion expressing “Relaxed (RL)” state

- Task 5

- To observe the “organic-like” motion expressing “Angry (AG)” state

4.1.5. Participants

4.2. Results

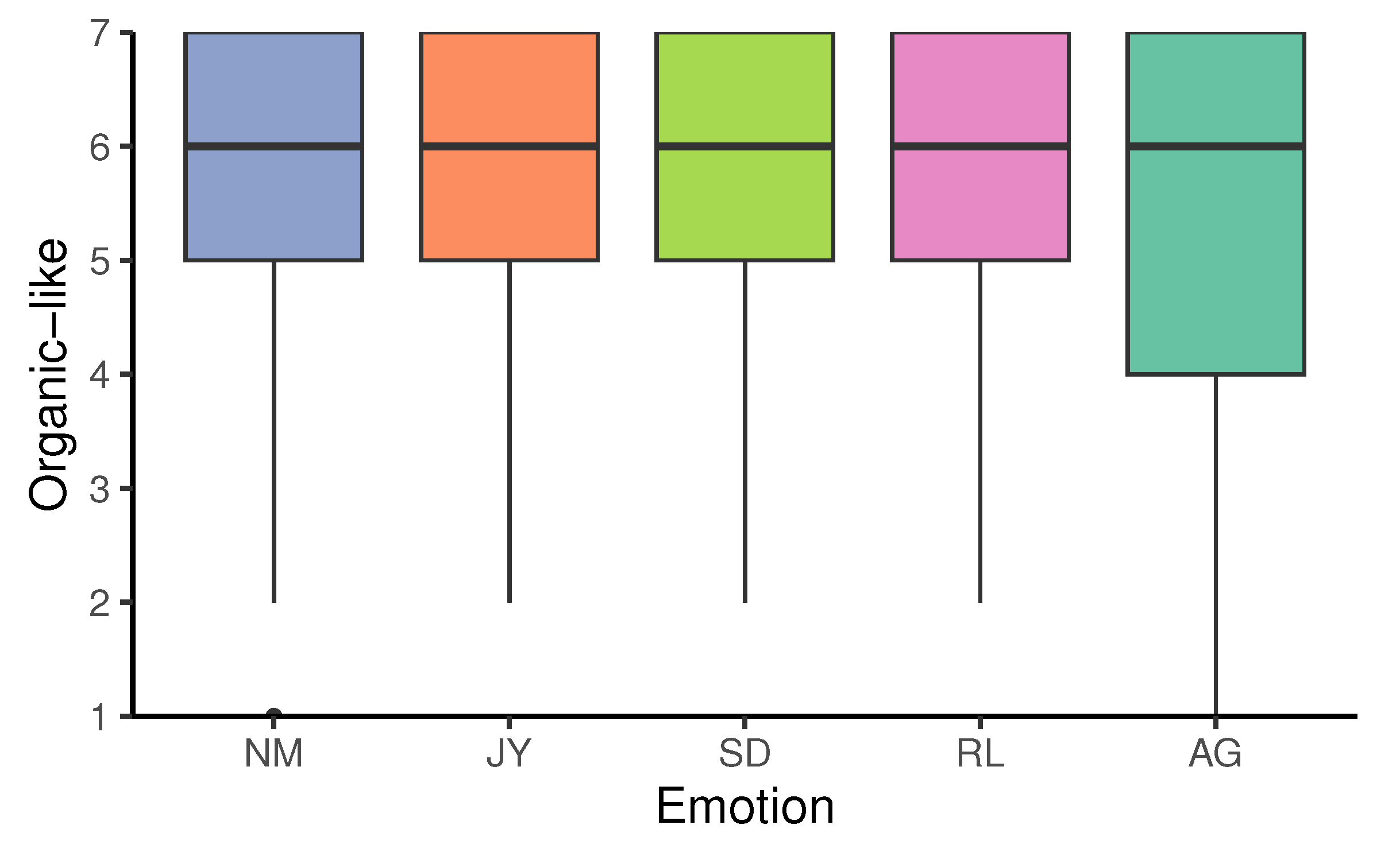

4.2.1. “Organic-like” perception

4.2.2. Arousal level

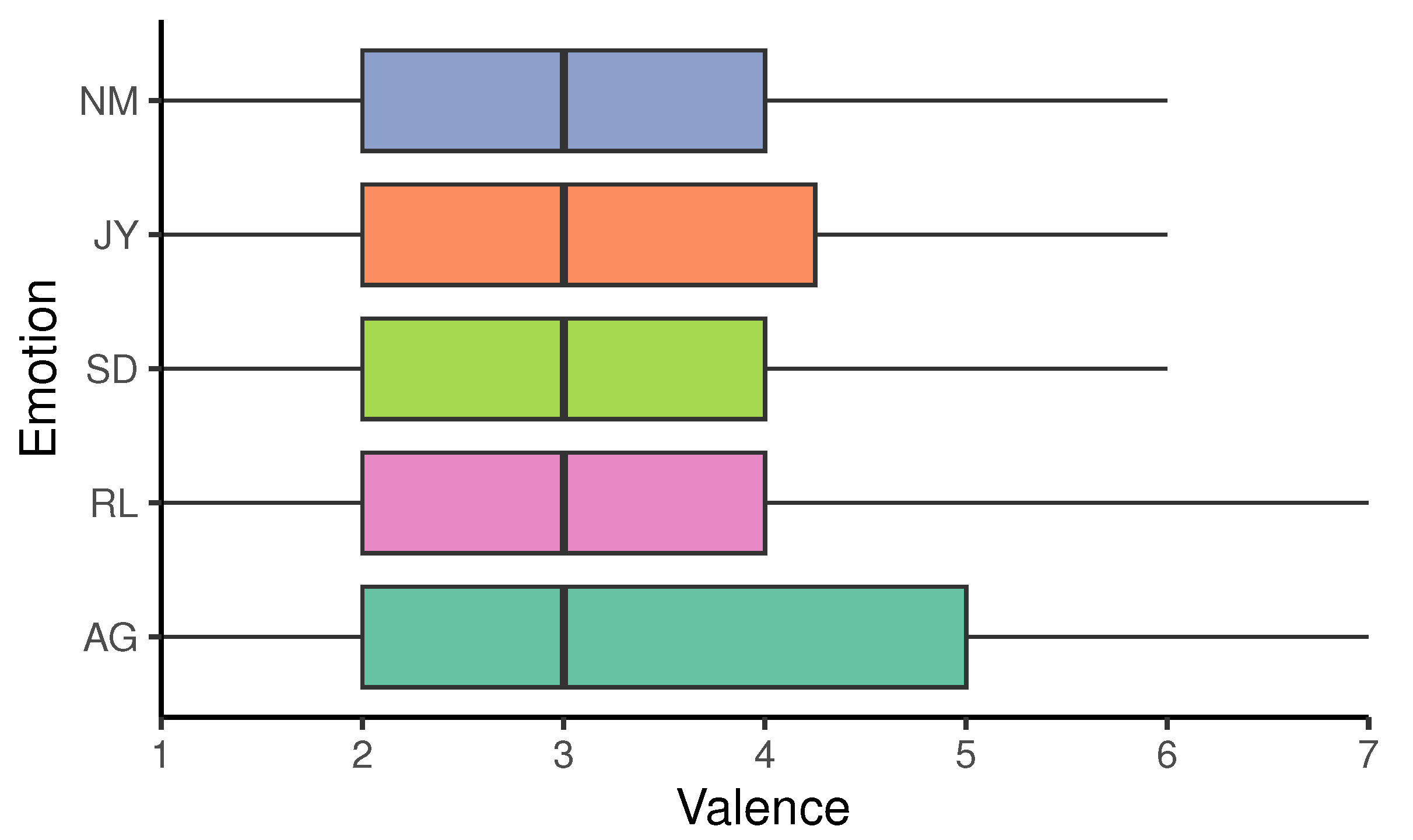

4.2.3. Emotional valence

4.2.4. Understanding of emotions

5. Discussion

5.1. Motion elements for animacy perception

5.2. Motion elements for expressing emotions

5.3. Emotional expression by motions perceived animacy

5.4. Limitation

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PC | Personal Computer |

| IDE | Integrated Development Environment |

| MTurk | Amazon Mechanical Turk |

| NCMB | NIFCLOUD mobile backend |

| URL | Uniform Resource Locator |

| JY | Joy |

| SD | Sad |

| RL | Relaxed |

| AG | Angry |

| NM | Normal |

| HITs | Human Intelligence Tasks |

| BH | Benjamini-Hochberg |

References

- Robinson, H.; MacDonald, B.; Kerse, N.; Broadbent, E. The psychosocial effects of a companion robot: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 2013, 14, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, H.; MacDonald, B.; Broadbent, E. Physiological effects of a companion robot on blood pressure of older people in residential care facility: a pilot study. Australasian journal on ageing 2015, 34, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, G.W.; Noronha, D.; Rivera, A.; Craig, K.; Yee, C.; Mills, B.; Villanueva, E. Effectiveness of a social robot,“Paro,” in a VA long-term care setting. Psychological services 2016, 13, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, S.; Houston, S.; Qin, H.; Tague, C.; Studley, J. The utilization of robotic pets in dementia care. Journal of alzheimer’s disease 2017, 55, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, M.M.A.; Allouch, S.B. The influence of prior expectations of a robot’s lifelikeness on users’ intentions to treat a zoomorphic robot as a companion. International Journal of Social Robotics 2017, 9, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, D.; Kaul, A.; Hurtienne, J. Expected behavior and desired appearance of insect-like desk companions. Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, 2017, pp. 289–297. [CrossRef]

- Minato, T.; Nishio, S.; Ogawa, K.; Ishiguro, H. Development of cellphone-type tele-operated android. Proceedings of the 10th Asia Pacific Conference on Computer Human Interaction. Citeseer, 2012.

- Hieida, C.; Matsuda, H.; Kudoh, S.; Suehiro, T. Action elements of emotional body expressions for flying robots. 2016 11th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI). IEEE, 2016, pp. 439–440. [CrossRef]

- Heider, F.; Simmel, M. An experimental study of apparent behavior. The American journal of psychology 1944, 57, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremoulet, P.D.; Feldman, J. Perception of animacy from the motion of a single object. Perception 2000, 29, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.H.; Troje, N.F. Perception of animacy and direction from local biological motion signals. Journal of Vision 2008, 8, 3–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, M.; Yamanaka, S. Perception of animacy by the linear motion of a group of robots. Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Human Agent Interaction, 2016, pp. 3–9. [CrossRef]

- Fukai, H.; Terada, K.; Hamaguchi, M. Animacy Perception Based on One-Dimensional Movement of a Single Dot. Human Interface and the Management of Information. Interaction, Visualization, and Analytics: 20th International Conference, HIMI 2018, Held as Part of HCI International 2018, Las Vegas, NV, USA, July 15-20, 2018, Proceedings, Part I 20. Springer, 2018, pp. 185–193. [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Egerstedt, M. From motions to emotions: Can the fundamental emotions be expressed in a robot swarm? International Journal of Social Robotics 2021, 13, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarinaimi, N.; Forlizzi, J.; Hurst, A.; Zimmerman, J. Breakaway: an ambient display designed to change human behavior. CHI’05 extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems, 2005, pp. 1945–1948. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hoffman, G. Using skin texture change to design emotion expression in social robots. 2019 14th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI). IEEE, 2019, pp. 2–10. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Tiab, J.; Šabanović, S.; Hornbæk, K. Happy moves, sad grooves: using theories of biological motion and affect to design shape-changing interfaces. Proceedings of the 2016 ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, 2016, pp. 1282–1293. [CrossRef]

- Elcanety. Office Room Furnituire. Available online: https://assetstore.unity.com/packages/3d/props/furniture/office-room-furniture-70884 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Follmer, S.; Leithinger, D.; Olwal, A.; Hogge, A.; Ishii, H. inFORM: dynamic physical affordances and constraints through shape and object actuation. Uist. Citeseer, 2013, Vol. 13, pp. 2501–988. [CrossRef]

- Siu, A.F.; Gonzalez, E.J.; Yuan, S.; Ginsberg, J.; Zhao, A.; Follmer, S. shapeShift: A mobile tabletop shape display for tangible and haptic interaction. Adjunct Proceedings of the 30th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, 2017, pp. 77–79. [CrossRef]

- Steed, A.; Ofek, E.; Sinclair, M.; Gonzalez-Franco, M. A mechatronic shape display based on auxetic materials. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 4758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, H.; Ueda, K. Interaction with a moving object affects one’s perception of its animacy. International Journal of Social Robotics 2010, 2, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, T.; Aizawa, Y. Theory of the intermittent chaos: 1/f spectrum and the Pareto-Zipf law. Progress of theoretical physics 1984, 71, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://tryoutartprogramming.blogspot.com/2015/11/1f-3.html (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Box, G.E.; Muller, M.E. A note on the generation of random normal deviates. The annals of mathematical statistics 1958, 29, 610–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack Technologies, LLC. slack. Available online: https://slack.com (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Amazon company. Amazon mechanical turk. Available online: https://www.mturk.com/ (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- unityroom. Available online: https://unityroom.com/ (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- FUJITSU CLOUD TECHNOLOGIES LIMITED. NIFCLOUD mobile backend. Available online: https://mbaas.nifcloud.com/en/ (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Google LLC. Google Forms. Available online: https://www.google.com/forms/about/ (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. Journal of personality and social psychology 1980, 39, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayram, Y.; Khan, M.M.H.; Jensen, T.; Nguyen, N. ... better to use a lock screen than to worry about saving a few seconds of time”: Effect of fear appeal in the context of smartphone locking behavior. Thirteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS 2017). USENIX Association, 2017, pp. 49–63.

| Questionnaire | Note | |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | I like creatures. | Only after Task 1 |

| Q2 | Why do you choose it in Q1? | Only after Task 1 |

| Q3 | Have you had any creatures? | Only after Task 1 |

| Q4 | a) What kind of creatures do/did you have?, b) I want to own any creatures. | Only the first time. If Q3 is “Yes”, a). If Q3 is “No”, b). |

| Q5 | What kind of creature(s) do you associate with the object’s movements? | |

| Q6 | What body parts of the creatures do you think closely resemble the object? | |

| Q7 | I valued the speed of the object. | |

| Q8 | I valued the height of the object. | |

| Q9 | I valued the randomness of the object. | |

| Q10 | The movement of the object I made felt “organic-like”. | |

| Q11 | What kind of movements do you think should add to this experiment’s object for feeling more “organic-like”? | Optional |

| Q12 | What kind of features do you think are necessary for an object to feel “organic-like””? | |

| Q13 | Comments about the experiment | Optional |

| None | 1/f noise | Normal Random Numbers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Low | High | ||

| Amplitude | 36 (56.3%) | 15 (23.4%) | 8 (12.5%) | 3 (4.69%) | 2 (3.13%) |

| Period | 46 (71.9%) | 8 (12.5%) | 5 (7.81%) | 4 (6.25%) | 1 (1.56%) |

| State | None | 1/f noise | Normal Random | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers | ||||||

| Low | High | Low | High | |||

| Amplitude | JY | −2 | −2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| SD | −4 | −1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| RL | 6 | −6 | −2 | 1 | 1 | |

| AG | −17 | −8 | 13 | 0 | 12 | |

| Period | JY | −4 | −3 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| SD | −2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| RL | 0 | 4 | −3 | −2 | 1 | |

| AG | −21 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 15 | |

| State | 1/f noise | Normal Random | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers | |||

| Amplitude | JY | 0.1174 | 0.7105 |

| SD | 0.05656 | 0.08837 | |

| RL | −0.02828 | 0.1167 | |

| AG | 0.2790 | 1.106 | |

| Period | JY | −0.04627 | −0.2695 |

| SD | −0.3394 | −0.1936 | |

| RL | −0.3111 | −0.4719 | |

| AG | −0.2545 | 0.07095 |

| State | Speed | Height | Randomness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Intensity | Frequency | |||

| NM | 3.498 | 1.525 | None | – | – |

| JY | 5.719 | 3.215 | None | – | – |

| SD | 1.923 | 0.8037 | None | – | – |

| RL | 1.879 | 1.169 | None | – | – |

| AG | 6.835 | 4.049 | (Amplitude) 1/f noise | 0.9764 | Low |

| Questionnaire | Note | |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | I like creatures. | |

| Q2 | Why do you choose it in Q1? | |

| Q3 | Have you had any creatures? | |

| Q4 | a) What kind of creatures do/did you have?, b) I want to own any creatures. | Only the first time. If Q3 is “Yes”, a). If Q3 is “No”, b). |

| Questionnaire | Note | |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | What creature(s) do you associate with the object’s movements? | |

| Q2 | What body parts of the creature do you think closely resemble the object? | |

| Q3 | What impression of the object’s movements do you have? | Pleasure–Displeasure |

| Q4 | What impression of the object’s movements do you have? | Arousal–Sleepy |

| Q5 | Which state do the object’s movements express? | |

| Q6 | The movement of the object felt “organic-like”. | |

| Q7 | What kind of movements do you think should add to this experiment’s object for feeling more “organic-like”? | Optional |

| Questionnaire | Note | |

|---|---|---|

| Q1 | What kind of features do you think are necessary for an object to feel “organic-like”? | |

| Q2 | Comments about the experiment | Optional |

| Answers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions | NM | JY | SD | RL | AG | |

| NM | 36.4% | 27.2% | 0% | 29.6% | 6.82% | |

| JY | 40.9% | 36.4% | 4.55% | 11.4% | 6.82% | |

| SD | 18.2% | 9.09% | 11.4% | 61.4% | 0% | |

| RL | 22.7% | 11.4% | 9.09% | 54.6% | 2.27% | |

| AG | 22.7% | 36.4% | 4.55% | 2.27% | 34.1% | |

| 1 | Slack is a trademark and service mark of Slack Technologies, Inc., registered in the U.S. and in other countries. |

| 2 | Amazon Web Services, AWS, the Powered by AWS logo, and MTurk are trademarks of Amazon.com, Inc. or its affiliates. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).