1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) belongs to the metabolic diseases and is a global crisis. It is the most frequent endocrine disease in children (rate 2/1000) and adolescents (5/1000), with children - almost always of the insulinopenic type (type I) - constituting 5% of the total population with diabetes. Type 1 diabetes is one of the most common chronic diseases of childhood, and its prevalence is increasing worldwide (1).

Type I DM is caused by insulin deficiency and must be treated with daily insulin injections. In the general population it accounts for 10% of all cases but is more common than type II DM in children (2).

The proposed treatment recommended for the management and treatment of DM, either for Type I or Type II, is complex and demanding since it requires daily control of blood glucose levels (at least 4 times a day), control and regulation of carbohydrate intake, frequent administration of insulin (3-4 injections a day or infusion from a pump), changing insulin doses to match eating and activity patterns, and testing urine for ketones when necessary (3,4).

DM affects mentally and physically the lives of the family as well as of the children, minors, and adults themselves. Next to the sick child stands the family as well as the child's social environment, which in turn is affected by the disease and the daily care they have to provide to their child. Both the child and its family during the announcement of the disease go through the stages, which are known as stages of mourning (i.e., "shock", "anger", "retreat", and "bargaining" (5), whereas there are four factors that can disturb the gradual and smooth development of the child with chronic diseases, whether this development is mental, social or emotional. Each phase of a chronic illness can present children and their families with significant challenges and stressors related to: 1) the separation – removal of the child from his family environment, 2) the deprivations in mobility and diet, 3) the effects of medical – nursing care, 4) the effects experienced by the child himself from the pain, physical disability and potential stigma (6.

The purpose of this brief literature review is to present the research findings which are related to the quality of life among parents of children and adolescents with diabetes by focusing on the entire system’s psychosocial wellbeing.

3. Results

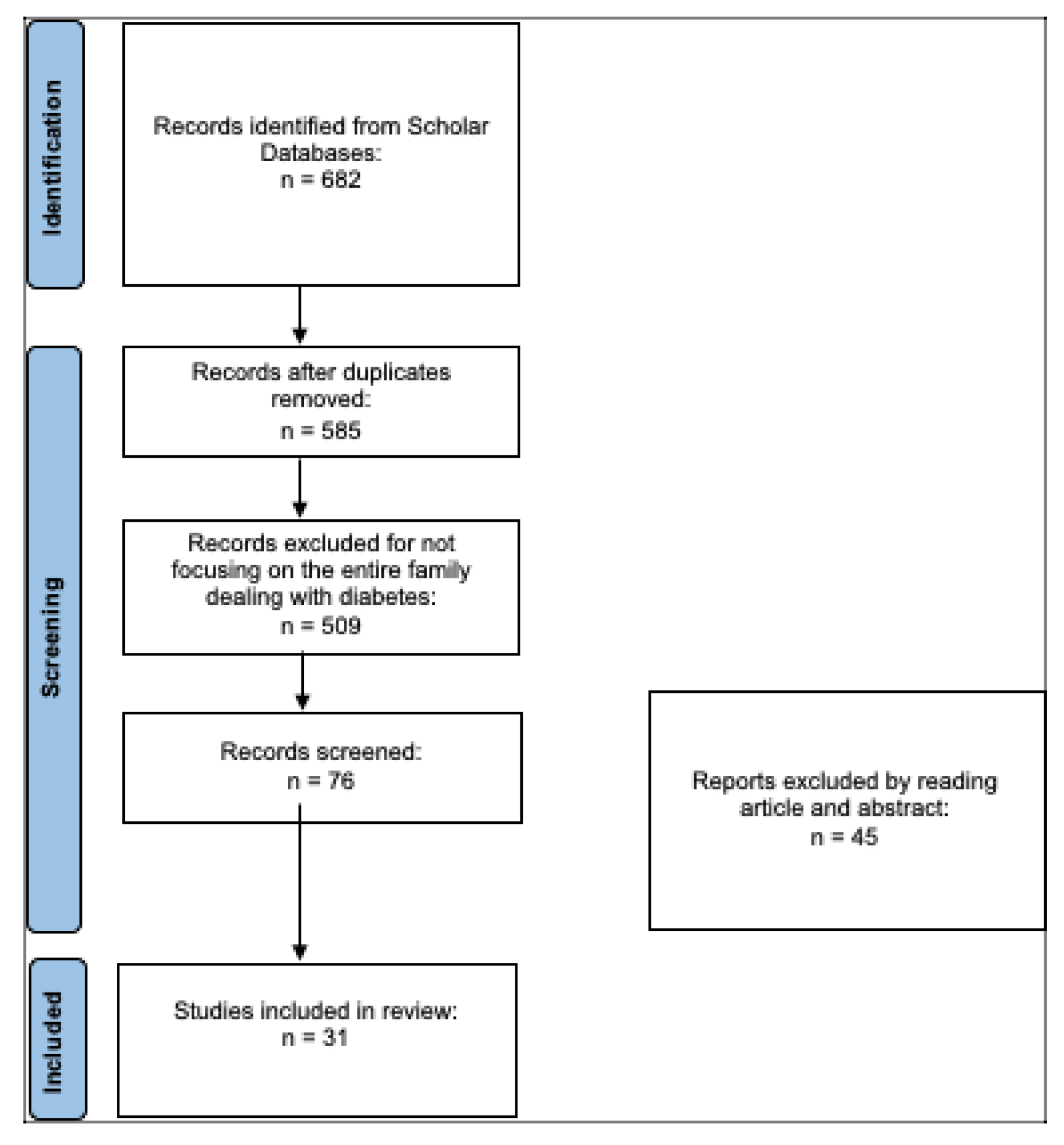

After searching the literature, 682 articles were found. At the end of the first screening, we selected 76 articles eligible for reading the whole text following the selection criteria described above. Finally, after checking the reference lists, 31 eligible articles were selected for the final analysis. A PRISMA flowchart of the selection and screening method is provided (

Figure 1).

3.1. Quality of life in parents of children and adolescents with diabetes

The diagnosis of a chronic illness or disability, such as diabetes, in a child leads to family upheaval and disorganization. The effects of this stress on parents can not only negatively affect the mental health of the parents but also affect the health of the child with diabetes. There have been several quantitative and qualitative studies in Greece and abroad which studied the burden and mental health of parents of children with diabetes.

Several studies have been carried out to measure the quality of life of the child and the impact that diabetes mellitus has on the family. One of them took place in Saudi Arabia, where a study was conducted involving 315 adolescent patients aged 12-18 years and their caregivers. The results of the study showed that adolescents in early adolescence (13-15 years old) had a better quality of life compared to adolescents (16-18 years old). This is attributed to the fact that the adolescent feels more autonomous and handles the insulin regimen by himself, with less parental influence, resulting in poor self-care management. Conversely, younger ages show a better quality of life. Through this study, the concern of parents with a child with diabetes mellitus was highlighted regarding the impact of the disease on the family as well as their concerns regarding the complications and treatments related to diabetes. Also, research results related to the family impact of the disease showed low impact rates, however these rates have a negative impact on parents' psychological well-being. (7).

Research carried out in the pediatric hospitals of Patras, Athens and Ioannina in the spring of 2016 with the aim of collecting data for the detection of socio-demographic factors that influence psychopathology, external shame and the experience of shame of parents with children suffering from diabetes. 285 parents of children with diabetes participated in this research. The findings of this particular study showed that the duration of the illness is associated with a reduced intensity of the phenomena in the psychology of the parents as over time the children take on part of the responsibility of managing the treatment thus partially relieving their parents. Also, over time, the parents themselves accept the disease as a part of their lives, thus reducing the consequences of the psychosomatic shock they had suffered when they first heard of the disease, as well as the consequences of internal and external shame. Also, the gender of the child played an important role compared to the degree of personal psychology. Girls showed lower rates of self-esteem and were less emotionally stable compared to boys. The same happens to parents as their psychology is influenced by their place of residence and their educational level 8).

Parents having children who attend secondary schools showed a better understanding of illness severity. Respondents residing in small towns had higher psychopathology values than parents of girls compared to parents of boys. An equally important finding of this study is that the origin of the child's name from the respondent parent's grandparent is an influencing factor of the scale of shame (ESS) with a greater influence of residents of small towns. In conclusion, through this research, it was pointed out that the supportive intervention for parents of children with diabetes should consider as factors of influence the place of residence, the educational level, the gender of the child as well as the origin of the child's name (8).

Another study was conducted in a pediatric endocrinology unit in Turkey and involved a total of 64 children aged 8-12 years and 85 adolescents aged 13-18 years with type 1 diabetes. The PedsQL was used to measure the quality of life of children and adolescents as well as their parents. The parent form had questions about marital status, education, and family income. There were also questions about whether the children had hypoglycemic attacks and how many, as well as how many times they needed to be taken to the hospital because of diabetes and the days of hospitalization. As for now the results of parents and children were relatively the same. The school life scale as well as the emotional scale was low, the social scale was high. A correlation was also observed between the Child and Adolescent Quality of Life Scale. A negative correlation was also found between the number of children and the quality of life of the child and parent (9).

A study carried out in Sweden with the participation of 130 families from four diabetes centers also studied the quality of life of parents and children (5-18 years) diabetes. The results of the research showed that parents were more identified with diabetes than their children and participated to a large extent in the management of diabetes and in fact they bear the greatest share of responsibility for the management of the disease and this is something that burdens them in to a great extent. The parents were the ones who perceive that the disease limits their child from many activities. Also during the research it was observed that there was a difference in the way of perception of the psychological influence between the gender of the child. In particular, girls often "freeze" when faced with psychological difficulties to a greater extent than boys (10).

Other researchers have studied the effect on the family of parents' overprotection towards their children and the problems that arise. The Parent Protection Scale was used to measure parental overprotection. 43 children (15 boys and 28 girls) aged 8-12 years and their mothers (28-48 years) participated. Results showed that parental stress was associated with high levels of children's depressive symptoms (11).

In another study carried out to compare the quality of life and health of young children with type 1 diabetes compared to their healthy peers, taking into account the family functioning and on-call of the mothers we had the following results. A total of 113 mothers provided data for the study, 28 of whom had preschool children with type 1 diabetes. There were no differences in quality of life and family functioning between children with diabetes and healthy children. Mothers of children with diabetes mellitus reported low levels of resilience and depressive symptoms to a greater extent than mothers of healthy children. In the regression analysis, mothers of children with diabetes mellitus showed that they are affected by their child's disease resulting in depressive symptoms and overall functioning family to be largely dependent on their child's illness. Mothers experience great discomfort with diabetes management, however, the family can function properly and young children can live in a similar way to that of their healthy peers. In conclusion, based on this study, the quality of life of preschool children is affected by the depression of their mothers. However, as mentioned above, there was no difference in functioning between families that have a child with diabetes or not, as this percentage is related to the child's quality of life, family functioning, mother's resilience, life satisfaction and well-being (12).

3.2. Family burden

Diagnosing diabetes in a child often causes reactions of intense anxiety, shock, sadness, grief, frustration, guilt and depression in the child's parents. Several studies have been conducted to study the burden of parents of children with diabetes and what makes this feeling more intense in these families. A study carried out in Norway wanted to show the similarities and differences between mothers and fathers regarding their degree of burden from caring for a child with diabetes. The aim was to demonstrate the degree of emotional distress among parents. 103 mothers and 97 fathers participated. The children in total were 115 aged 1-15 years. The result of this research showed that both mothers and fathers reported that heavier weight was related to long-term anxiety about their child's health. Mothers reported a high burden related to the medical care required to care for their child, feeling more emotional stress than fathers. Nighttime scores are significantly related to parental burden and emotional stress experienced by both sexes (13).

Another study done by Hatton et al. (14) identified 3 different phases of parental coping with an infant or young child with diabetes. In the long-term phase, increased stress, sadness, frustration, anger and loss of control were observed on the part of the parents. These feelings become more intense as the child grows and has other deceptions about the food he consumes, which leads to a confrontation between the parents and the child with as a result, the former often want to entrust the care of their child to others, in cases of increased blood glucose levels and the fear of hypoglycemic shock, but also for fear about the future of their child.

Faulkner (15), investigated parents and siblings of children with diabetes and found that mothers of children with diabetes remembered the time when the diagnosis was made and reported the intense emotions they experienced such as shock, anger and denial. Many mothers mentioned the pain they feel every time they measure their children's glucose and how painful this process is for them.

Dashiff (16) in her study found the great burden of mothers who, as they reported, are overwhelmed by grief. Grief apparently exists in these families but it is unclear whether it is caused by the turmoil brought on by adolescence or is part of the ongoing turmoil brought on by the disease. End of a study of Eakes et al. (17) found the disparity experienced by parents of children with diabetes as they face daily situations that remind them that their children have special needs and cannot have a completely normal life. Parents of children with diabetes often describe what they are going through as a period of constant confusion, guilt, fear, and in some cases intense sadness (18).

Another study conducted in 2007 involving 17 parents of children with diabetes in whom 10-17 years had passed since the diagnosis of the disease found that the parents had adapted to the needs of diabetes management but most had not "come to terms" with the diagnosis. They experienced many times a resurgence of their grief during the development of their child, many of the mothers who were upset during the interviews were upset even though 10-17 years had passed since the first diagnosis. Mothers processed their emotions more than fathers and finally both parents experience feelings of sadness, pain and anger (19).

Another study approved by the Yale School of Nursing Human Research Review Committee and involving 28 mothers of children with diabetes addressed the burden and emotions experienced by families of children with diabetes. The results of this study showed that mothers of children with diabetes are in constant vigilance, have constant concerns about hypoglycemia and care for their children. There were many mothers who felt insufficient support for this and the necessity of supporting structures is emphasized through the study (20). Study which aimed to examine the daily experience of mothers of children with diabetes, showed their concern regarding the fear they have in case of hypoglycemia of their child and an epileptic episode (21). Another study involving 27 subjects addressed the burden experienced by parents of children with diabetes. The conceptual framework of this study was based on insights derived from Orem's deficit theory this -care. The results of the survey showed that the parents recognized that their family life changed when they learned about their child's illness and they feel constant confusion about the course of the illness as well as about the future of their children (22).

Another qualitative study, whose authors interviewed 30 parents about their experiences raising a child with diabetes. This analysis revealed 6 themes that focus on parental concerns and are as follows: 1) long-term complications of diabetes, 2) challenges from disease management, 3) financial concerns, 4) child mental health, 5) health coverage and 6) experiences with people outside the family and at school (23). Parents of children with diabetes struggle to balance diabetes management and standard parenting, challenges that can lead to burnout. Although burnout is a familiar term, in the diabetes literature there is a dearth of references to the exhaustion experienced by parents of these children. Twenty - one videos addressing the burnout of parents of children with diabetes were used in this qualitative descriptive study. Based on the statistics the results were that the issues related to this exhaustion are stress, inability to control diabetes, sadness and getting a normal life (24).

Finally, another study by Jean and colleagues that aimed to show the way parents communicate with their children suffering from diabetes and if this way is sufficient for both sides to be able to express and solve the problems that arise. The results of the study showed that there is a large degree of frustration with this communication. Both parents and children expressed insecurity and fear in expressing their feelings, something that leads parents to psychological pressure and a permanent stress, which wears them down psychologically (25).

3.3. The stress of parents

The effects of parental stress lead to mental disorders of the parents which also affect the health of the child with diabetes. So not only does the family affect diabetes but diabetes also affects the family. A study conducted with the participation of 132 teenagers with diabetes and which lasted 5 years, with the participation of their parents, showed that the stress of the parents, which is related to diabetes, is the one that leads to poor mental health of them and also of their children. Among other things, this study examined parental stress and the influence it has on the mental health of the parents as well as the relationship that parental stress has on the health of the child with diabetes (26). Another study of 69 fathers of children with chronic diseases such as diabetes studied the prediction of post-traumatic stress in the fathers of these children. The results of this study showed that fathers with high levels of stress are at greater risk of post-traumatic stress. Finally, the severity of stress was related to the duration of the disease diagnosis. Fathers with a duration of 6 months since the diagnosis of the disease had more stress than those who had passed a year since the diagnosis (27).

A study investigating the pediatric stress experienced by fathers of a child with diabetes showed that they themselves experience low levels of pediatric stress, but the correlates of father stress may have effects on general family functioning as well as children's behavior. This study builds on the literature by investigating correlates of fathers' pediatric stress in a sample of young children with type 1 diabetes. Forty-three fathers of children (2-6 years) with diabetes completed the self-report questionnaire (28). Another study examined the stress faced by parents and involved 134 parents of children with diabetes. The analyzes showed that the stress experienced by parents is multifaceted and related to the age of the child and the socio-economic status of the family (29). Finally, another study in which 102 parents participated investigated parental stress and the results found were that parents of children newly diagnosed with diabetes are at risk of developing depression as well as feeling that their lives have changed, with resulting in them experiencing a constant emotional discomfort (30).

A study by Lowes and colleagues, which aimed to gain a new theoretical understanding of parental reactions and adjustment processes to the disease, showed that the diagnosis of childhood diabetes leads to a psychosocial transition for parents. This transition is the grieving process and the stages of adjustment that parents experience. In all these stages, parents experience strong emotions such as stress, depression, guilt, fear as they are overwhelmed by an uncertainty regarding the outcome of the disease and the life of their children (31).

A descriptive study conducted in 2016 involving one hundred and thirteen parents of children and adolescents with diabetes in Shiraz and using Depression Anxiety Scales (DASS-21) and Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale aimed to identify psychological predictors of resilience in parents of children and adolescents who are insulin dependent. The results showed that the parents had high levels of stress, with 71.4% reporting mild to extremely severe symptoms of depression and anxiety. Additionally, 49% of changes in resilience are due to factors such as stress, depression and life satisfaction. Since nearly half of the parents experienced anxiety, depression, and stress, and there was a correlation between resilience and these psychological variables, parents' psychological problems, especially depression, may be reduced by improving their resilience (32).

Every disease, like diabetes, creates significant levels of stress, affecting the psychological well-being of parents as well as children. Consequently this has negative implications regarding disease management. The aim of the study by Antonio Zayas and his colleagues was to study the levels of depression in parents and to analyze the resilience these parents had. 31 parents of children with diabetes were evaluated, by the JEREZ diabetic association. The results of the study showed that these parents showed moderate levels of depression. It was also found that those who were more resilient also had lower levels of depression (33). Another study by Luo and colleagues was conducted to determine whether resilience moderates the detrimental effects of caregiver burden on quality of life between caregiver and children with diabetes. The study involved 227 parents and the results showed that caregiver burden was associated with parents' quality of life, while resilience was found to be positively associated with quality of life. Resilience served as a moderator between caregiver burden and mental health. When parents faced high caregiver burden, the benefit of high resilience to better mental health was evident (34).

Another study referred to by Koegelenberg investigates the properties of resilience and concludes that family communication, the routine of everyday life, the time a family spends together are important characteristics of resilience and influence the adjustment of families with a child diagnosed with diabetes (35). Ozlem Kara and colleagues studied the relationship between the levels of anxiety and depression of children with type 1 diabetes and the resilience of their parents' coping attitudes. The study involved 71 parents and children with diabetes, and the results showed that parents with children who have a chronic disease show different coping attitudes. These behaviors cause various effects on the child. In conclusion, families that use appropriate coping strategies have a positive impact on their children (36).

4. Discussion

Diabetes mellitus is a challenge for the patient himself but also for his family who are suddenly faced with a condition that causes changes in the functioning of the whole family, especially when it comes to a small child or teenager. Primary health care must provide support to these families so that they can overcome in the smoothest possible way all the transitional stages from the information of the disease to the acceptance of their child's disease. The parents, as we have seen through the above studies in which they participated, felt strong feelings of stress, anger, pain which, through appropriate support from experts, will be normalized as much as possible, which will lead them to a more functional behavior so that they can accept the disease. Parents who showed increased levels of depression, overprotection and stress transmitted anxiety and symptoms of depression to their child.

The recognition of the influence of socio-demographic factors on the psychopathology of parents highlights the need for targeted interventions helping them to become more effective in supporting their children in dealing with the disease of diabetes mellitus.

The above observations raise new questions about the psychological processes associated with the occurrence of diabetes mellitus, a disease that inevitably affects the unconscious perceptions and associations of the parent in relation to the child and creates new questions which, to the extent that they cannot to answer create guilt and increase stress and indicators of psychopathology. Sudden adverse change could produce feelings of inferiority which in turn are related to shame, anxiety and depression (37).

In the context of therapeutic interventions, the role of caregivers is very important, because of the care they offer. It is critical that their needs can be understood and the burden on their lives assessed. Thus, appropriate interventions will be able to be designed to at least limit the burden on caregivers by focusing on the individual factors that contribute to this phenomenon. In this context, it is proposed that a research effort should be made to this direction.