1. Introduction

Substitutional energy sources have drawn the public’s attention in recent years due to the consequences of fossil fuel consumption. One of the alternative energy sources is hydrogen (H

2), an energy carrier that allows energy transport in a usable form from one place to another[

1]. Clean hydrogen can be produced in several ways, such as through electrolysis. However, one of the lucrative approaches is the dry reforming of methane (DRM) process, which uses greenhouse gases as feedstock to produce synthesis gases (H

2 and CO). There are a few drawbacks to the DRM reaction. First, it needs more than 700°C to reach optimal efficiency and conversion [

2]. This is energy intense. Second, the coking formation occurs at high temperatures. Several transition metals and noble metals, including Rh, Ni, Ir, Ru, Pt, and Co, are known to be active as DRM catalysts. The active metals are usually dispersed as small (nanoscale) particles supported on porous ceramic supports, such as Al

2O

3, and SiO

2 [

3], through catalytic synthesis methods. However, Ni is the most suitable active metal due to its comparatively lower cost to upscale production to the industrial scale. Despite the economical price of Ni, Ni catalysts suffer inevitably from rapid deactivation caused by coke deposition, or active metal sintering or both [

4] and it is less stable compared to the other noble catalysts. The rate of carbon deposition was reported to decrease with rising reaction temperature [

5]. However, the increment in temperature is not a reasonable way to stop carbon deposition due to energy use concerns. Several researchers reported an improvement of the temperature reduction in thermal catalysts for the DRM reaction, such as Rh, Ni, Pd, Co, Ir, and Ce supported on Al

2O

3 and SiO

2 [6-9]; nonetheless, these require a trade off with the higher cost of noble metals. Recently, a unique way of designing catalysts using plasmonic nanoparticles (NPs) has appeared to be an attractive approach for the DRM reaction to reduce the operating temperature. The plasmonic/metal NPs interact with light incidents, such as sunlight or light sources with heat, by transferring photoexcited charge carriers from metal NPs to the reactants, leading to chemical transformations under less energy-intense conditions. In this case, it is ideally possible to target electronic excitation so that only DRM reactions are activated. This leads to the sustainability goals by lowering the operating temperature that traditionally runs at high temperatures and by improving the selectivity of reactions that may undergo side reactions.

Sugar is one of the top export products from Thailand. However, despite all the profits from the sugar industry, sugar production generates massive waste materials, such as bagasse, press mud, and spent wash[

10]. Biomass waste from sugar production, like bagasse, could be used as fuel for thermal power plants or boiler stations to produce energy that can be fed back into sugar production. However, residuals ash from burning bagasse would be disposed of at landfills, which could bring about other environmental issues caused by the bagasse ash.

The current study focused on utilizing waste materials (bagasse ash) and modifying their properties as a catalyst support for photothermal catalyst in the DRM reaction compared with a commercial support catalyst (SiO2). Furthermore, we used a conventional wet impregnation approach to obtain Ni/SiO2 catalysts in a synthesis design strategy.

2. Results and Discussion

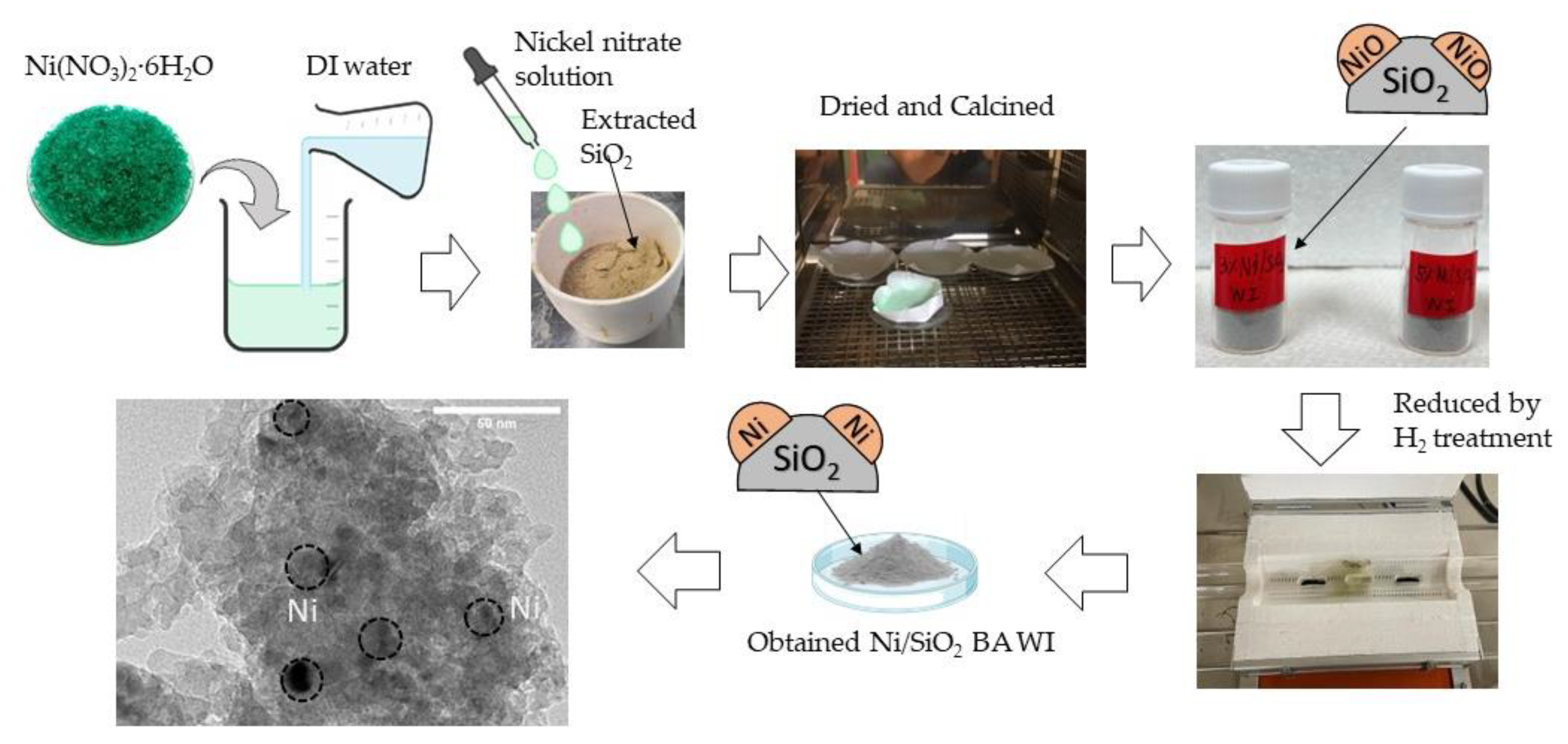

2.1. Fabrication of The Catalyst Support Preparation And Synthesis Catalyst

In this work, catalyst support was prepared by extracting SiO

2 from bagasse ash using an acidic extraction approach (3% HCl reagent grade), then modifying its properties by KOH activation at a ratio of 1:4 [

11] to maximize the surface area of extracted SiO

2. For catalyst synthesis, Ni/SiO

2 was synthesized by conventional wet impregnation. There are two mechanisms of wet impregnation. One relies on capillary action to draw the solution into the pores. The other is that the solution transport changes from a capillary action process to a diffusion process in the wet impregnation method [

12].

2.2. Characterization

The synthesized catalyst surface area was analyzed using an Autosorb® iQ3 gas sorption analyzer (Anton Paar QuantaTec Inc.; USA), in which adsorption-desorption isotherms take place with liquid nitrogen’s help at -195 °C. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) technique was used to calculate the catalyst surface area within the pressure range of 0.12 to 0.20. X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded using a diffractor (XRD; Rigaku, Smartlab; Japan) axial diffractometer in the 2θ = 10° to 80° angular arrays with a step of 0.05°s-1 for the synthesized catalysts. Then, the synthesized catalysts were analyzed using X-ray fluorescence (Epsilon 1; Malvern Panalytical Ltd.; UK) for elemental analysis to confirm the chemical composition of the catalysts in percentage terms. Additionally, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the synthesized catalysts were measured using Schottky field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; SU8030; Hitachi-High Tech Corp.; Japan). The SEM images captured the surface morphology of the catalysts, and the EDS mapping checked the dispersion of Ni particles and the composition of the catalysts. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were taken on a Jeol-JEM-2100Plus; Japan operated at 200 kV. Specimens were prepared by suspending sample powders in ethanol; then, and a drop of the suspension was deposited on copper grids.

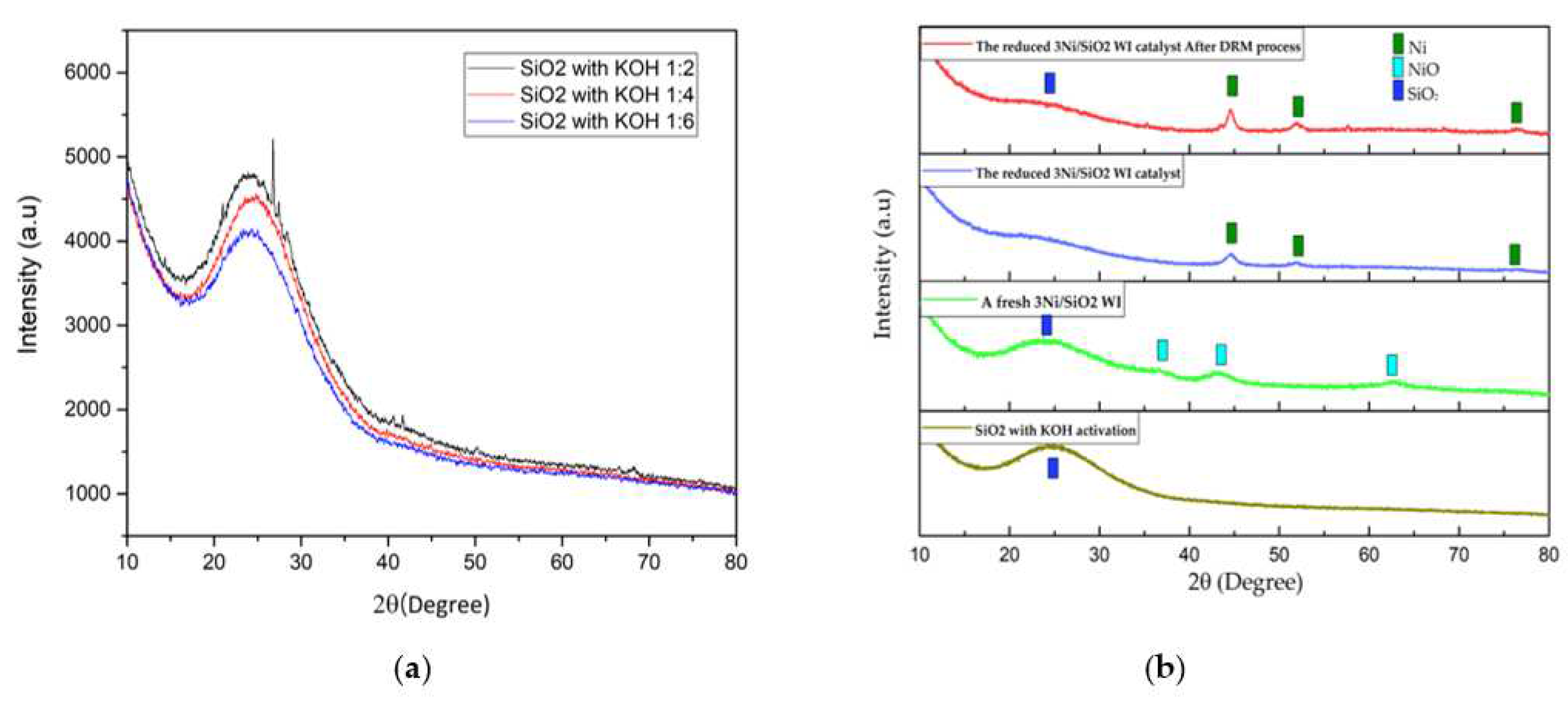

2.2.1. XRD Analysis

As shown in

Figure 2a, extracted SiO

2 was extracted by acidic extraction using HCl and followed by KOH activation at various ratios 1:2-1:6. These samples were characterized by X-ray diffraction analysis. The amorphous SiO

2 can be detected at 24.3°. The optimal ratio of KOH activation (SiO

2: KOH) was 1:4 [

11]. Additionally, the XRD pattern of 3Ni/SiO

2 BA WI shows in

Figure 2b, obtained by the Wet Impregnation approach. For a fresh 3Ni/SiO

2 catalyst (light green line), the diffraction peaks appearing at 37.1°, 43.1°, and 62.5° can be attributed to the NiO phase (JCPDS 65-2901), while the broad peak at 24.3° can be identified to the SiO

2 phase (JCPDS 39-1425)[

13]. The XRD pattern of the reduced 3Ni/SiO

2 catalyst (blue line) also shows in

Figure 1B which the diffraction peaks at 2θ = 44.3°, 51.4°, and 76.1°, which can be indicated by the crystal planes of (111), (200), and (220) of metallic nickel phase. Finally, the reduced 3Ni/SiO

2 WI catalyst after the DRM process (red line) shows that the XRD pattern demonstrated identically to the reduced 3Ni/SiO

2 WI catalyst (blue line) without the appearance of the diffraction peaks of carbon.

2.2.2. BET Surface Analysis

The BET analysis results are shown in

Table 1. The BET surface area of the commercial SiO

2 was 10.7 m

2/g, which changed slightly to 11.4 and 12.6 m

2/g in the 3 and 5 Ni/SiO

2 commercial WI samples, respectively. The BET surface area of the extracted SiO

2 with KOH activation at a ratio 1:4 was 185 m

2/g, which marginally declined to 163 and 157 m

2/g in the 3 and 5 Ni/SiO

2 BA WI, respectively (

Table 1). From the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method, the average pore sizes of the commercial SiO

2, the extracted SiO

2 with KOH activation, 3,5Ni/SiO

2 commercial WI, and 3,5Ni/SiO

2 BAWI were 4.47, 20.2, 4.62, and 20.9 nm, respectively.

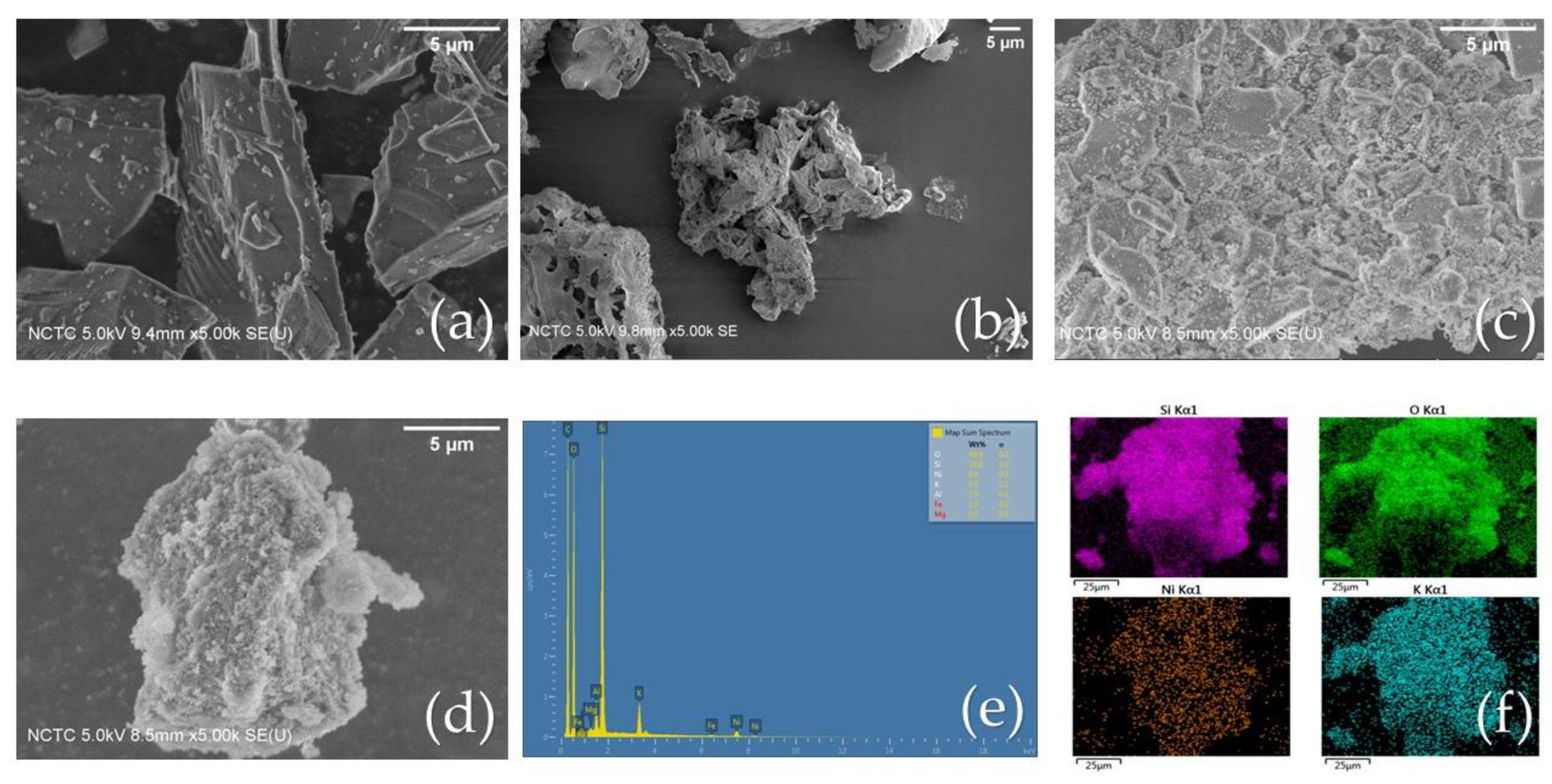

2.2.3. SEM Analysis

As shown in

Figure 3, the internal microstructures of the bare commercial SiO

2, extracted SiO

2 and the Ni/SiO

2 commercial WI were examined using SEM analysis, while EDS elemental mapping was used for the Ni/SiO

2 BA WI. The bare commercial SiO

2 is shown in

Figure 3a, with a regular, smooth surface.

Figure 3b shows an image of the extracted SiO

2 from BA with a complicated structure and a rough surface.

Figure 3c,d represent synthesized Ni/SiO

2 commercial WI and Ni/SiO

2 BA WI, respectively. As seen, the Ni particles were successfully decorated on both the commercial SiO

2 and extracted SiO

2 BA surfaces. Furthermore, the extracted SiO

2 BA exhibited a complicated structure with a high surface area, which would be beneficial for photothermal catalytic activity. The EDS element spectra of the Ni/SiO

2 BA composite are shown in

Figure 3e, which confirmed not only the presence of Ni, Si, and O but also residual inorganic elements, such as Mg, Al, Fe, and K, on the synthesized catalyst.

Figure 3f demonstrates the dispersion of Ni particles onto the catalyst support (SiO

2).

2.2.4. XRF Analysis

Despite the EDS elemental mapping, XRF analysis helped to estimate the composition of the synthesized catalyst. The XRF analysis results indicated that Ni and SiO

2 were not only in the obtained samples, but there were also other residual elements, such as Al and K, as shown in

Table 2. In contrast, the XRF analysis of Ni/SiO

2 commercial WI only exhibited Ni and Si as shown in

Table 3.

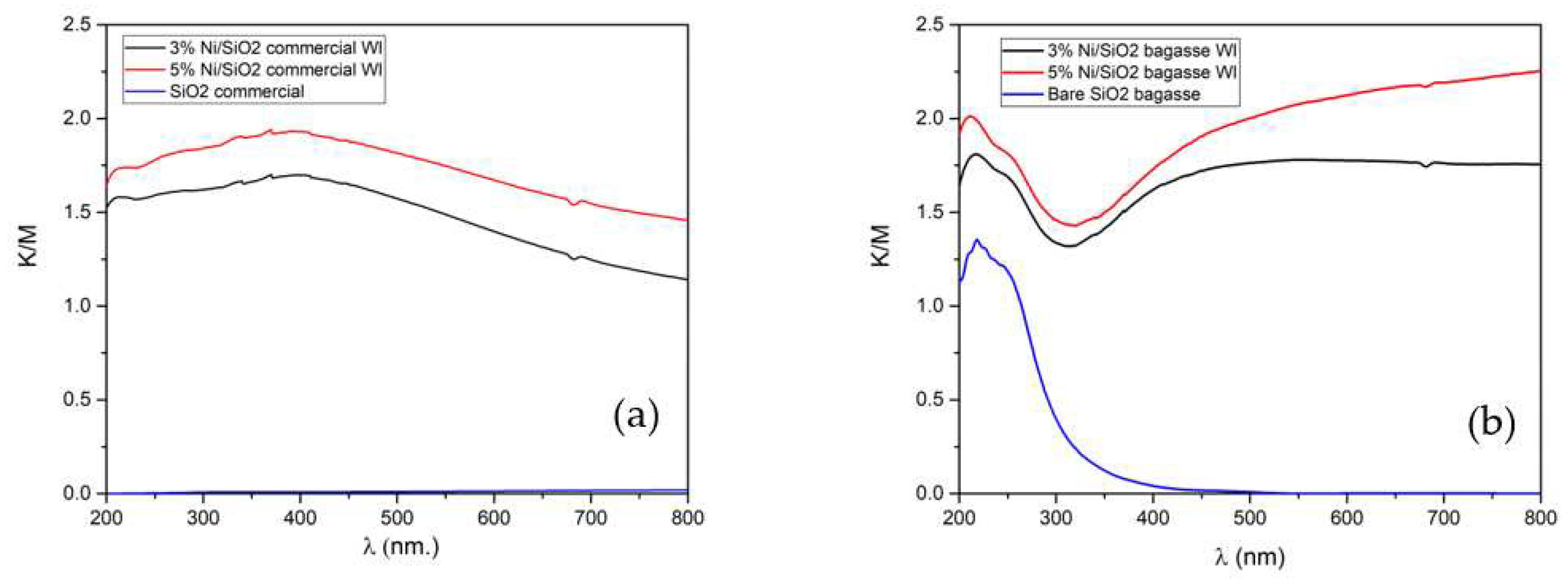

2.2.5. Optical Properties

The optical properties of the synthesized photothermal catalysts were evaluated using ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy. The UV-Visible diffuse reflectance spectrum (UV-Vis DRS) of bare SiO

2 commercial, extracted SiO

2 BA, 3,5Ni/SiO

2 commercial WI, and 3,5Ni/SiO

2 BA WI are shown in

Figure 4a,b. The UV-Vis DRS of the commercial SiO

2 had a non-absorption edge at all wavelengths (blue DRS line in

Figure 4a). In contrast, after the wet impregnation method, 3,5Ni/SiO

2 commercial WI exhibited an increment of absorption edge around 370 nm and strong absorption over a wide range of the UV and visible light regions (black and red DRS lines in

Figure 4a). At the same time, the UV-Vis DRS of the extracted SiO

2 from BA had an absorption edge around 230 nm (blue line in

Figure 4b). It is because not only extracted SiO

2 from bagasse ash contain pure SiO

2, but it also consists of inorganic residuals such as Al, K, Mg, and Fe, which could add light adsorption properties to our extracted SiO

2 sample. Furthermore, after the wet impregnation method, 3,5Ni/SiO

2 BA WI demonstrated a similar trend to 3,5Ni/SiO

2 commercial WI, with an increment of strong absorption over a wide range of the UV and visible light regions (black and red DRS lines in

Figure 4b).

2.3. Photothermal Catalytic Activity

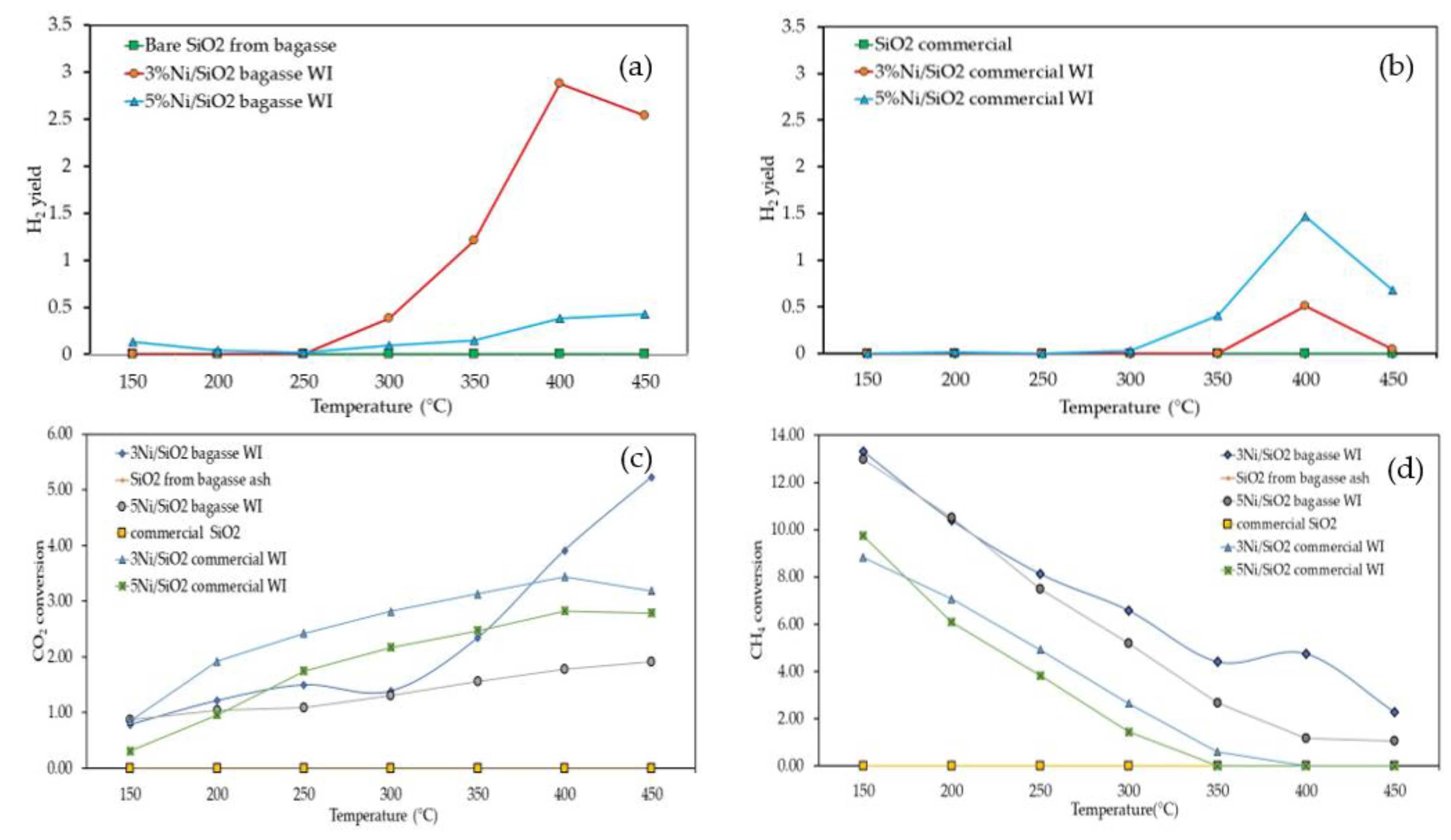

2.3.1. Photothermal Catalytic hydrogen Generation Results and Analysis

The photothermal catalytic activities of the synthesized catalysts were examined based on CH

4, CO

2 conversion, and H

2 yield under UV-visible light irradiation. To investigate the efficient catalytic activity between different catalyst supports (commercial SiO

2 and extracted SiO

2 from bagasse ash), their catalytic performance toward H

2 generation was carried out under UV-visible light from an Hg-Xe lamp. The biomass-derived catalysts (Ni/SiO

2 BA WI) had higher activity than the commercial SiO

2 catalyst support one, as shown in

Figure 6a,b because the surface area of Ni/SiO

2 BA WI was substantially higher than for the Ni/SiO

2 commercial WI, which could be attributed to higher activity. In addition, the light-adsorption ability of the extracted SiO

2 BA was enhanced after the wet impregnation method (

Figure 4b) compared to the commercial SiO

2 before the wet impregnation method, which reflected light in all ranges. Therefore, it could interact with UV-visible light after the wet impregnation method (

Figure 4a).

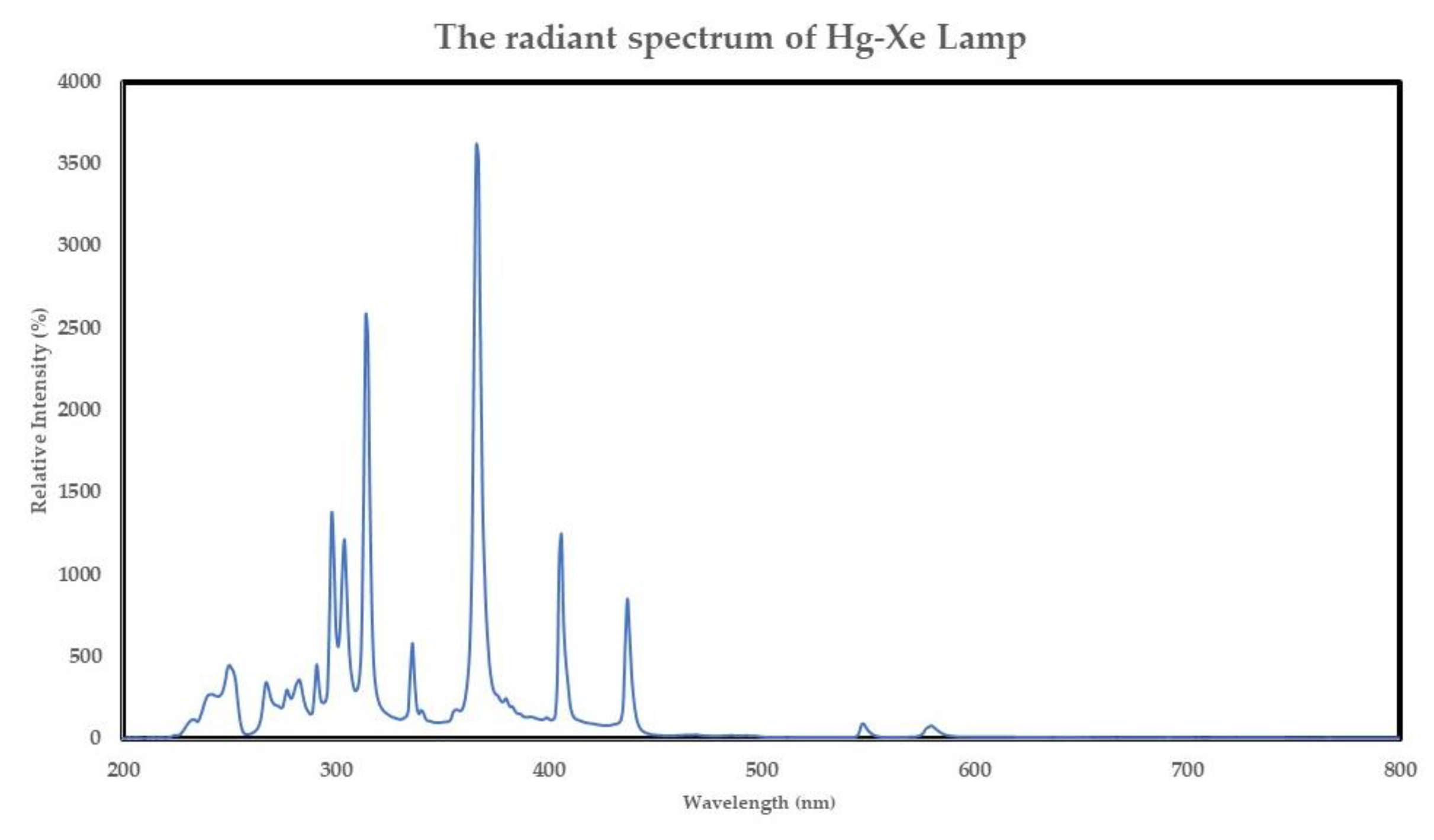

Figure 5 shows the relative intensity of the Hg-Xe lamp, which was intense in 200-450 nm range.

2.3.2. Band alignment and proposed photothermal catalytic mechanism

Amorphous silica has a wide band gap energy of approximately 7.62–9.70 eV [

14]; thus, the valence band electrons are relatively difficult to excite to the conduction band even when irradiated by UV light. However, the interband excitation in Ni particles was more favorable, with the photogenerated hot electrons overcoming the energy barrier. The hot carriers generated from the light-induced d-to-s interband excitation in Ni nanoparticles are proposed to mediate the transformation of photon energy to chemical energy. The relaxation of hot carriers increased the surface temperature of the catalyst and, more importantly, the separated hot carriers were directly involved in the chemical reaction[

15].

To investigate the optimal Ni percentage amount on the synthesized catalysts with light irradiation, the photothermal catalytic performance of 3,5Ni/SiO

2 BA WI and 3,5Ni/SiO

2 commercial WI were tested in relation to the CH

4 and CO

2 conversions.

Figure 6a,b revealed that 3Ni/SiO

2 BA WI had the highest catalytic activity. However, when the content of Ni increased to 5%, the CO

2 conversion and H

2 yield were reduced, perhaps due to the agglomeration of nickel particles on the catalyst support. In addition, the light adsorption property of Ni/SiO

2 BA WI could have increased the surface temperature on the catalyst support, leading to sintering, which subsequently resulted in catalyst deactivation and reduced 5Ni/SiO

2 BA WI performance.

In contrast, the CH

4 conversion of all synthesized catalysts showed a downward trend, indicating that the CH

4 reactant was consumed in the system, as shown in

Figure 6d. An increase in the temperature resulted in reduced CH

4 conversion. Furthermore, H

2O appeared in the system.

The experimental results demonstrated that Ni particles on extracted SiO

2 from bagasse ash could interact with UV light to generate hydrogen at 300 °C because the UV-visible light provides photon energy to stimulate the Ni particles, leading to a plasmonic effect in the metal nanoparticles that creates electron-hole pairs (called hot carriers) and initiates the DRM reaction (eq. 1). However, when the temperature increased, the H

2 yield dropped at 450 °C and H

2O was detected in the system. Preferable reaction pathways, such as a reverse water gas shift reaction (eq. 2) at low temperatures (200–350 °C) may have resulted in a side reaction and unwanted products, such as H

2O in this case.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of Bagasse Fly Ash

Bagasse fly ash was received from A Sugar Production Company (Thailand) after being burned as biomass fuel for the boiler. It contained a high moisture percentage; thus, it was necessary to dry the bagasse fly ash at 80 °C in a dry oven overnight followed by drying at 105 °C in an oven for 2 hours. After drying, the bagasse fly ash was fed into a crucible and burnt in a furnace at an initial temperature of 400 °C, a heating rate of 1 °C/min, and a holding time of 2 hours to de-volatized any organic compounds. Then, the ash was heated to 900 °C to de-carbonize it and held for 2 hours at the same heating rate to obtain crystalline silica.

3.2. Preparation of Silicon Dioxide Extraction

Bagasse fly ash was washed with 3% HCl reagent grade at a ratio of 12 ml 3% HCl per 1 g of bagasse fly ash as an extraction agent to reduce impurities other than SiO2 in the bagasse fly ash. The washed ash was stirred using a magnetic stirrer at 240 rpm for 2 hours on a hotplate at 200 °C. After mixing, the sample was cleaned using deionized water until the pH was neutral. Afterward, the sample was passed through a vacuum filter containing filter papers and dried at 80 °C in a dry oven overnight. Then, the sample was calcined at 400 °C at a heating rate of 1 °C/min and cooled in the oven.

3.3. Preparation of KOH Activation For Silicon Dioxide

Silica dioxide is chemically activated by potassium hydroxide (KOH) at SiO2-to-KOH ratios ranging from 1:1 to 1:8 to obtain SiO2 particles with greater surface areas. The resulting mixed SiO2 samples (~3 g) and KOH (1:1 to 1:8) were added to 100 mL of DI water and then stirred at 70 °C for 1 hour. After mixing, the samples were dried in the oven at 80 °C overnight until all the liquid had evaporated. Subsequently, each sample was placed in a ceramic crucible and calcined under an air atmosphere at 800 °C (heating rate 5 °C/min) for 1 hour. During the calcination process, porosity was induced in the silica structure by the combustion of K2O derived from the KOH reaction. Next, the activated products were stirred with 2.5% HCl reagent grade to eliminate residual K2SiO3 in the samples. Afterward, the mixture was washed with DI water repeatedly to dissolve any KCl until the pH was neutral, followed by vacuum filtration to separate the solids from the liquid. Finally, the solid product was dried at 80 °C overnight to obtain the activated SiO2 with a high surface area.

3.4. Preparation of Catalysts

Wet impregnation method

Nickel(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2 · 6 H2O) is dissolved with DI water to obtain a Nickle nitrate solution. Then, a Nickle nitrate solution is dropped on the activated SiO2 powder and mixed with a spatula. Subsequently, the samples are dried at 100 °C overnight and calcined at 600 °C for 2 hours to obtain a Ni/SiO2 -WI.

3.5. Photothermal DRM activity test

The photothermal activities of the powder samples were measured under ambient pressure in a flow reactor with a quartz window[

16], which enabled us to irradiate the powder samples with a 150 W Hg–Xe lamp (Hayashi-Repic, LA-410UV-5; Japan).. Approximately 10 mg of catalyst powder was put into a reactor; in sequence, the gas mixture CH

4: CO

2: Ar = 1: 1: 98 in vol% was continuously supplied to the reactor at a flow rate of 10 mLmin

-1. The generated hydrogen was measured using a micro gas chromatograph (Agilent, 3000 Micro GC; USA).

4. Conclusions

The Ni particles on extracted SiO2 from bagasse ash (Ni/SiO2 BA WI) and SiO2, fabricated using acidic extraction and KOH activation, could drive the photothermal catalytic DRM reaction under UV light. Compared to Ni particles on commercial SiO2 (Ni/SiO2 commercial WI) with light irradiation, the Ni/SiO2 BA WI could generate more H2 products. In addition, light irradiation lowered the initiation temperature of syngas generation to 300 °C. However, the maximum H2 yield was only 3%., As an assumption, the hot carriers generated from light-induced d to s interband excitation in the Ni particles played a vital role in our study, mediating the transformation of photon energy to chemical energy and driving the DRM reaction, despite the side reactions, such as the RWGS reaction. Therefore, we suggest that the use of extracted SiO2 from bagasse ash as the catalyst support provides a perspective on substitute materials for a practical path to establish a plasmonic or non-plasmonic hot carrier-based photothermal catalytic system. The concept presented in this study showed the possibility of the utilization of waste materials as a solution for energy reduction in H2 production. We expect that this concept will contribute to the progress of green energy and photothermal catalysis in the field of heterogeneous catalysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MM, SK, TRS, and IK; Investigation, IK, HK; methodology, IK and SK; Supervision, MM, TRS; Writing–original draft, IK; writing—review and editing, MM, TRS.

Funding

This research received funding through a TAIST-Tokyo Tech scholarship, National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA), Thailand and the Faculty of Engineering, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Remme, S.B.a.U. The Future of Hydrogen. IEA 2019, Technology report.

- Arora, S.; Prasad, R. An overview on dry reforming of methane: strategies to reduce carbonaceous deactivation of catalysts. RSC Advances 2016, 6, 108668-108688. [CrossRef]

- Kee, R.J.; Karakaya, C.; Zhu, H. Process intensification in the catalytic conversion of natural gas to fuels and chemicals. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 2017, 36, 51-76. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, D.; Tian, D.; Jiang, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, K. Optimization of Ni-Based Catalysts for Dry Reforming of Methane via Alloy Design: A Review. Energy & Fuels 2022, 36, 5102-5151. [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, S.; Kondratenko, E.V.; Pohl, M.-M.; Barkschat, A.; Rodemerck, U. Stable low-temperature dry reforming of methane over mesoporous La2O3-ZrO2 supported Ni catalyst. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2012, 113-114, 19-30. [CrossRef]

- Barama, S.; Dupeyrat-Batiot, C.; Capron, M.; Bordes-Richard, E.; Bakhti-Mohammedi, O. Catalytic properties of Rh, Ni, Pd and Ce supported on Al-pillared montmorillonites in dry reforming of methane. Catalysis Today 2009, 141, 385-392. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Aparicio, P.; Guerrero-Ruiz, A.; Rodrı́guez-Ramos, I. Comparative study at low and medium reaction temperatures of syngas production by methane reforming with carbon dioxide over silica and alumina supported catalysts. Applied Catalysis A: General 1998, 170, 177-187.

- Hou, Z.; Chen, P.; Fang, H.; Zheng, X.; Yashima, T. Production of synthesis gas via methane reforming with CO22 on noble metals and small amount of noble-(Rh-) promoted Ni catalysts. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2006, 31, 555-561. [CrossRef]

- Ranjekar, A.M.; Yadav, G.D. Dry reforming of methane for syngas production: A review and assessment of catalyst development and efficacy. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society 2021, 98. [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, S.; N, P. Recovery of Chemicals from Pressmud – A Sugar Industry Waste. Journal of Indian Chemical Engineer 2006, 48, 160-163.

- Kanaphan, Y.; Klamchuen, A.; Chaikawang, C.; Harnchana, V.; Srilomsak, S.; Nash, J.; Wutikhun, T.; Treethong, A.; Rattana-amron, T.; Kuboon, S.; et al. Interfacially Enhanced Stability and Electrochemical Properties of C/SiOx Nanocomposite Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2022, 9, 2200303.

- Deraz, N.M. The comparative jurisprudence of catalysts preparation methods: I. Precipitation and impregnation methods. 2017.

- Ding, F.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, G.; Wang, K.; Dragutan, I.; Dragutan, V.; Cui, Y.; Wu, J. Synthesis and Catalytic Performance of Ni/SiO2for Hydrogenation of 2-Methylfuran to 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran. Journal of Nanomaterials 2015, 2015, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Güler, E.; Uğur, G.; Uğur, Ş.; Güler, M. A theoretical study for the band gap energies of the most common silica polymorphs. Chinese Journal of Physics 2020, 65, 472-480. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Peng, X.; Yamaguchi, A.; Ueda, S.; Fujita, T.; Abe, H.; Miyauchi, M. Photocatalytic Partial Oxidation of Methane on Palladium-Loaded Strontium Tantalate. Solar RRL 2019, 3. [CrossRef]

- Takeda, K.; Yamaguchi, A.; Cho, Y.; Anjaneyulu, O.; Fujita, T.; Abe, H.; Miyauchi, M. Metal Carbide as A Light-Harvesting and Anticoking Catalysis Support for Dry Reforming of Methane. Global Challenges 2019, 4. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).