Submitted:

02 May 2023

Posted:

02 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

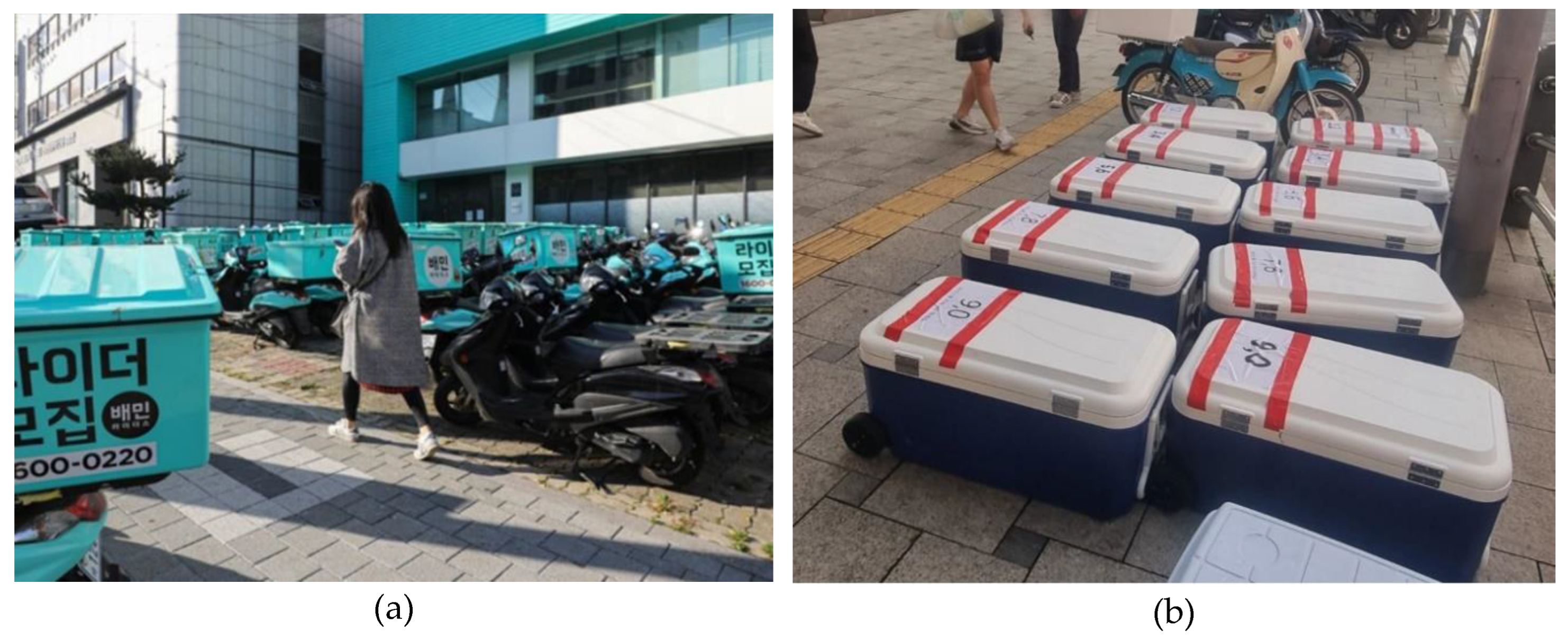

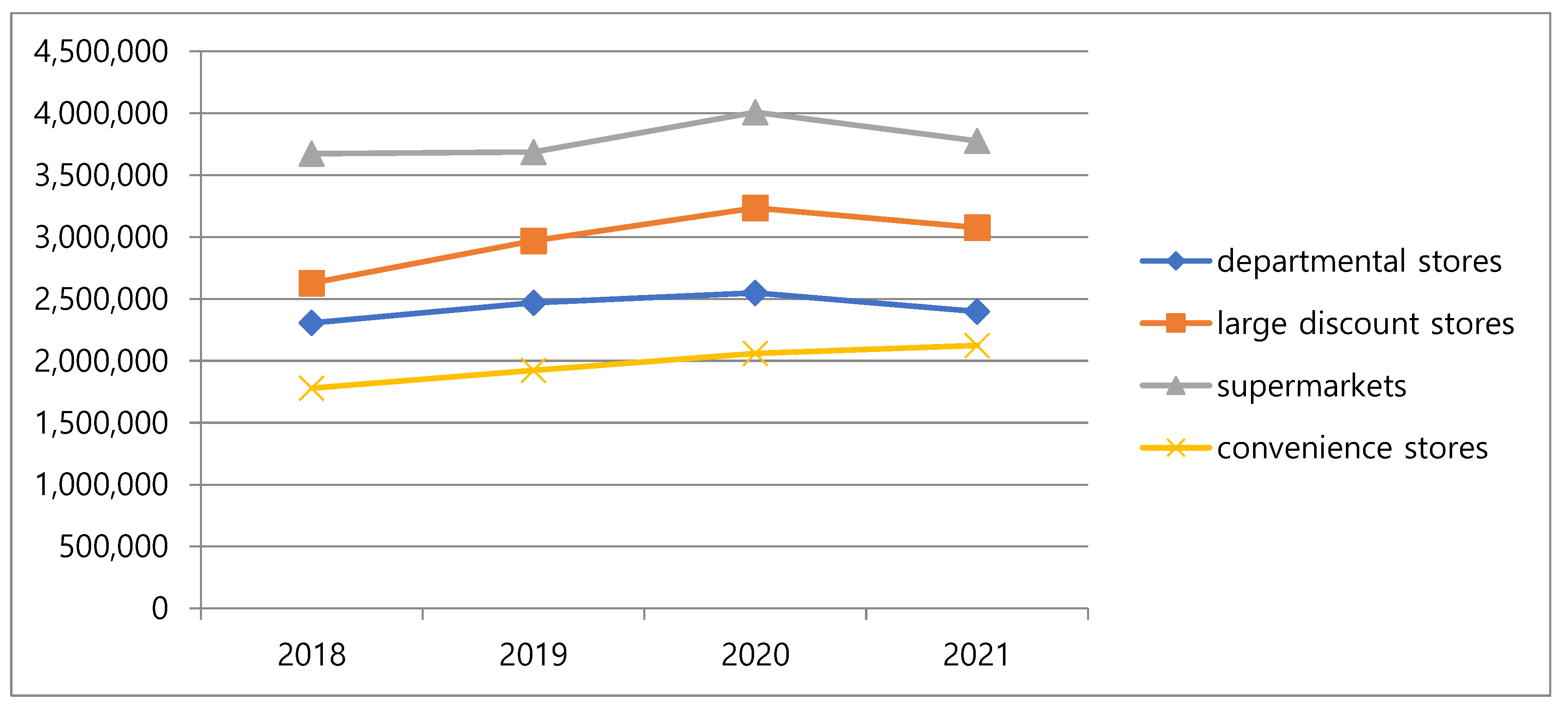

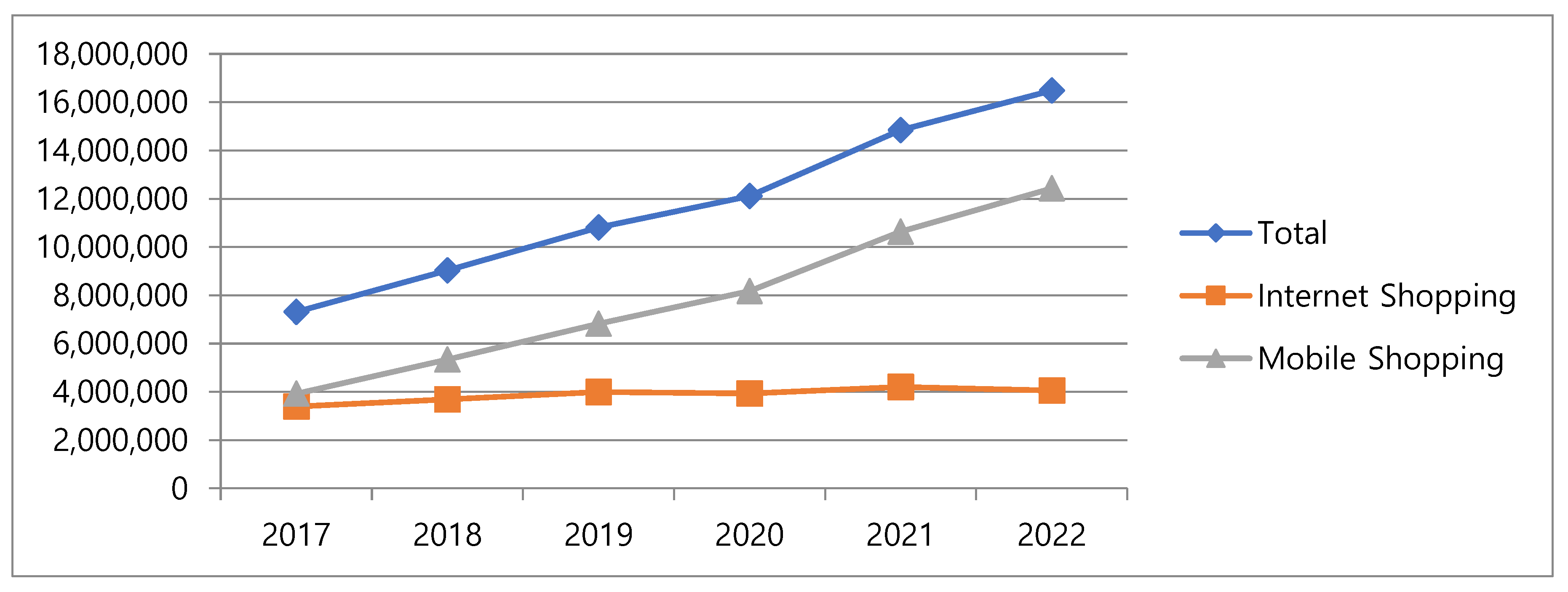

2.1. Changes in Commercial Environment and Emergence of Dark Stores in South Korea During COVID-19

2.2. Possible Changes to the Urban Environment Caused by Dark Stores

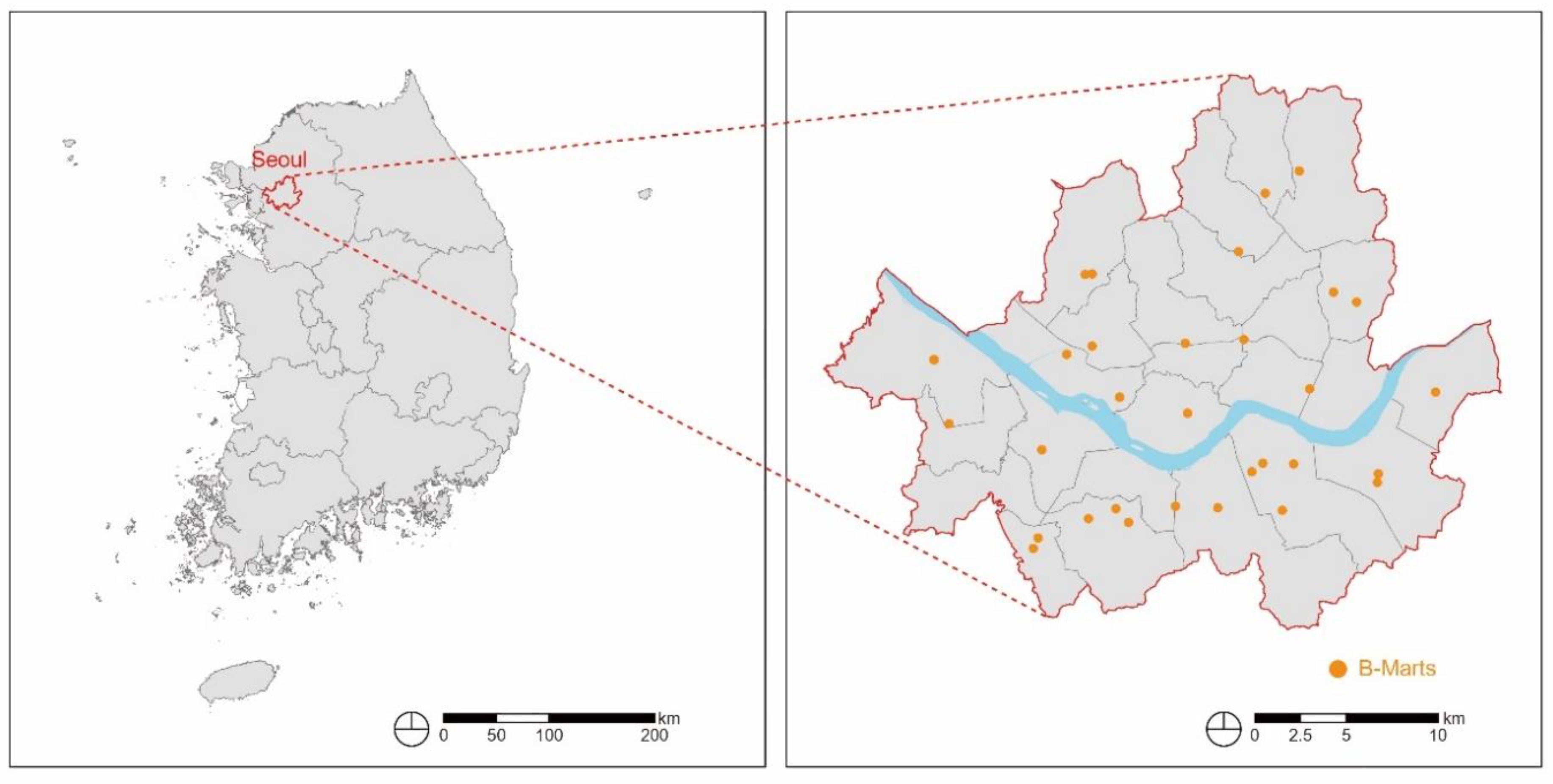

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Do B-Marts Negatively Affect Land Use?

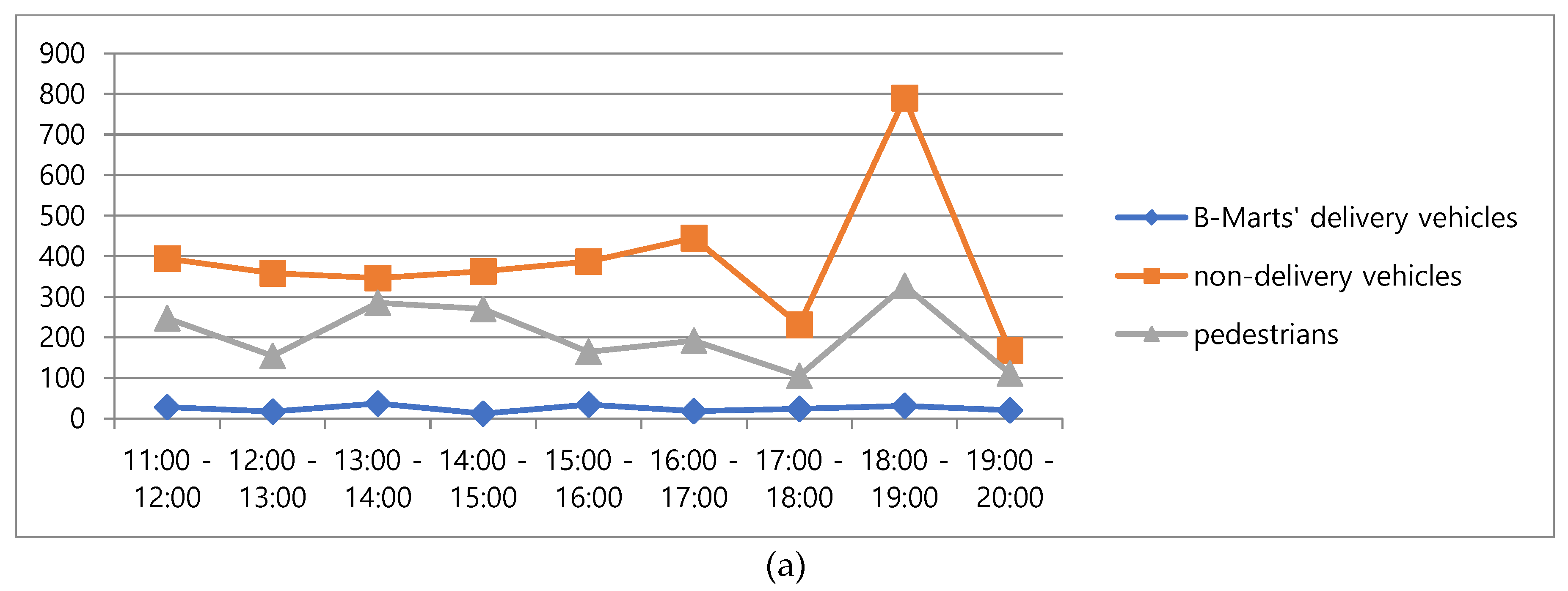

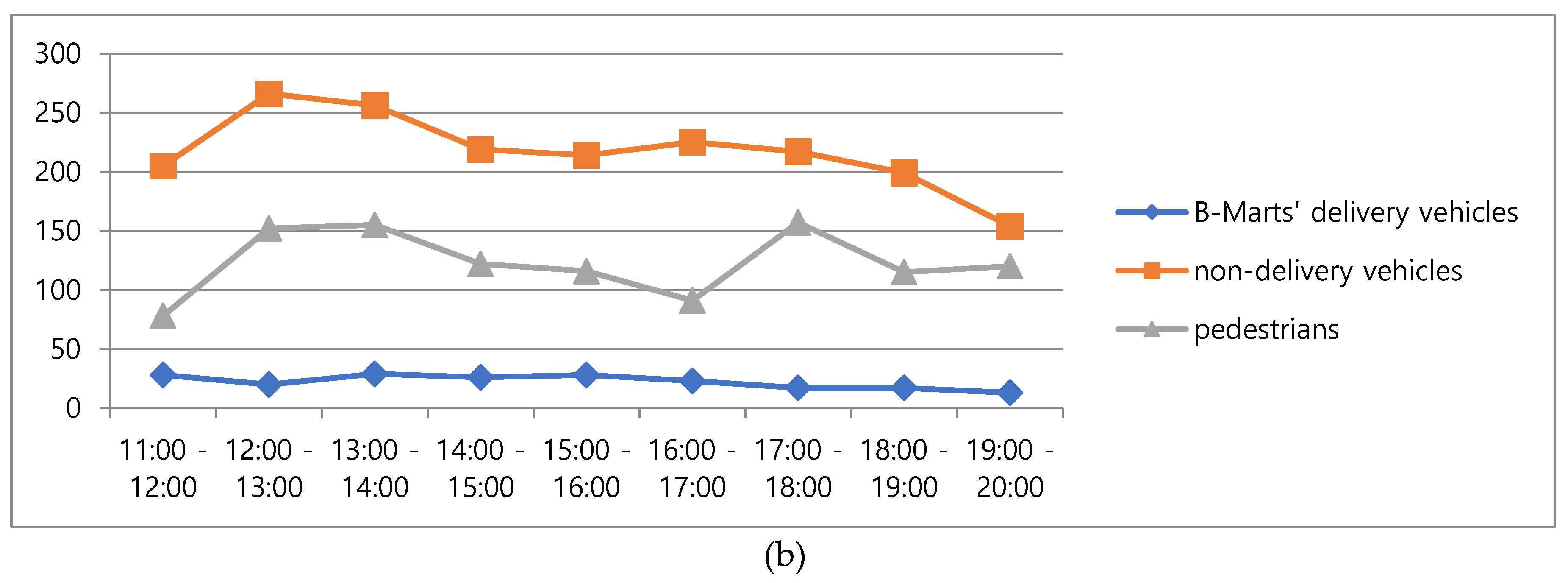

4.2. Do B-Marts Negatively Affect Traffic?

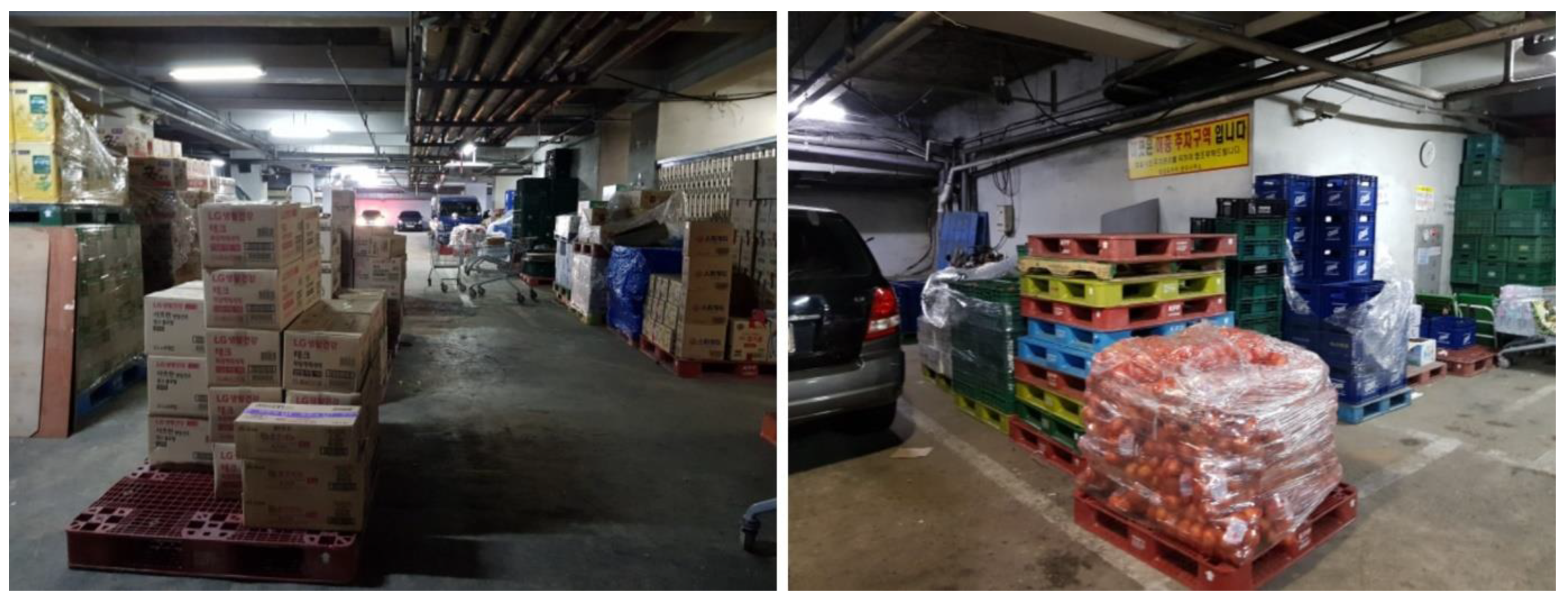

4.3. Does B-Mart Negatively Affect the Streetscape?

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pantic, M., Cilliers, J., Cimadomo, G., Montano, F., Olufemi, O., Mallma, S. T., Berg, J. Challenges and opportunities for public participation in urban and regional planning during the COVID-19 pandemic- Lessons learned for the future. Land 2021, 10(12), 1–19.

- Hashem, T. Examining the influence of COVID 19 pandemic in changing customers' orientation towards e-shopping. Mod Appl Sci 2020, 14(8), 59–76. [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E., Pizzi, G., Scarpi, D., Dennis, C. Competing during a pandemic? Retailers’ ups and downs during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Bus Res 2020, 116, 209-213. [CrossRef]

- Eger, L., Komárková, L., Egerová, D., Mičík, M. The effect of COVID-19 on consumer shopping behaviour: Generational cohort perspective. J Retail Cons Serv 2020, 61, 1 –11. [CrossRef]

- UNCTAD. COVID-19 and E-commerce: findings from a survey of online consumers in 9 countries. 2020. Retrieved from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3886558/. Accessed December 21, 2022.

- Jensen, K. L., Yenerall, J., Chen, X., Yu, T. E. US consumers’ online shopping behaviors and intentions during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J Agricul Appl Econ 2021, 53(3), 416434. [CrossRef]

- Music, J., Charlebois, S., Toole, V., Large, C. Telecommuting and food E-commerce: Socially sustainable practices during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Transpt Res Interdiscip Perspect 2022, 13, 100513. [CrossRef]

- Shen, H., Namdarpour, F., Lin, J. Investigation of online grocery shopping and delivery preference before, during, and after COVID-19. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect 2022, 14, 100580. [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, O., & Karjaluoto, H. Online grocery shopping before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A meta-analytical review. Telematics Informatics 2022, 71, 13101839. [CrossRef]

- Forbes. Lasting changes to grocery shopping after Covid-19? 2020. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/blakemorgan/2020/12/14/3-lasting-changes-to-grocery-shopping-after-covid-19/?sh=2af98f5e54e7 Accessed September 2, 2022.

- Shapiro, A. Platform urbanism in a pandemic: Dark stores, ghost kitchens, and the logistical-urban frontier. J Consum Cult 2022, 23, 168–187. [CrossRef]

- Nobre, J. M. N., Vita, J. B. Analysis of the dark store from the perspective of urban law. Revista de Direito da Cidade 2021, 13(3), 13731392.

- Ahn, K. H., Cho, J. W., Han, S. Introduction to Marketing Channel Management. Hakhyunsa, 2019.

- Lee, C. Analysis on Critical Success Factors on Electronic Commerce –with Internet Shopping Mall-. [Unpublished Master’s Thesis]. Hanyang University, 2000.

- Santos, V. F., Sabino, L. R., Morais, G. M., Goncalves, C. A. E-Commerce: A short history follow-up on possible trends. Int J Bus Admin 2017, 8(7), 130–138. [CrossRef]

- Kang, D. Expansion of online shopping and changes in retail structure. Labor Rev 2021, 191, 719.

- Choe, Y., Lee, J. K., Kim, J. Changes in the distribution industry environment due to COVID-19 and the prospect of distribution regulations. J Law Econ Reg 2021, 14(2), 60 –86.

- Kim, J. T. Changes in the retail industry during the COVID-19 Era. Food Industry and Nutrition 2021, 26(10), 911.

- National Information Society Agency. 2019: A survey on Internet use. Daegu, South Korea, 2020.

- National Information Society Agency. 2020: A survey on Internet use. Daegu, South Korea, 2021.

- National Information Society Agency. 2021: A survey on Internet use. Daegu, South Korea, 2022.

- Kim, M. “So many deliveries”. Even a street icebox. Korea Herald (2021, July 21). Retrieved December 22, 2022, from https://mbiz.heraldcorp.com/view.php?ud=20210721001010.

- Back, S. W., Kim, S. H. Post-COVID-19, directions and challenges of agri-food distribution. Kor J Organ Agri 2021, 29(1), 1–23.

- Jung, Y. B. Post-COVID-19, changes in consumption structure by distribution channels of major livestock products - Based on the results of animal products distribution information survey in the second quarter of 2020. Kor Soc Food Sci Animal Res 2020, 9(2), 74–81.

- Wikipedia. Dark store. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_store/. 2022. Accessed December 21, 2022.

- Gurran, N., Phibbs, P. When tourists move in: How should urban planners respond to Airbnb? J Am Plan Ass 2017, 83(1), 80 –92. [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, S., Udell, A. Do Airbnb properties affect house prices? 2016. Retrieved from https://web.williams.edu/Economics/wp/SheppardUdellAirbnbAffectHousePrices.pdf. Accessed January 6, 2023.

- Zervas, G., Proserpio, D., Byers, J. W. The impact of the sharing economy on the hotel industry: Evidence from Airbnb's entry into the Texas Market. In EC ‘15 Proceedings of the Sixteenth ACM Conference on Economics and Computation, Portland, Oregon. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Choi, K. H., Jung, J., Ryu, S., Kim, S. D., Yoon, S. M. The relationship between Airbnb and the hotel revenue: In the case of Korea. Ind J Sci Tech 2015, 8(26), 1–8.

- Horton, T. Reducing affordability: The impact of Airbnb on the vacancy rate and affordability of the Toronto rental market. [Unpublished Master’s Thesis]. University of Ottawa, 2016.

- Lee, D. How Airbnb short-term rentals exacerbate Los Angeles’s affordable housing crisis: Analysis and policy recommendations. Harvard Law Pol Rev 2016, 10, 229–253.

- Jefferson-Jones, J. Can short-term rental arrangements increase home values?: A case for Airbnb and other home sharing arrangements. Cornell Real Est Rev 2015, 13, 10–19.

- Yoon, J. "Coupang It's Mart" chasing after B Mart. Competition for the delivery app "Quick Commerce" is in full swing. Voice of the people (2021, November 17). Retrieved December 22, 2022, from https://www.vop.co.kr/A00001602941.html.

- Kwon, Y. B Mart in Wongok-dong, Ansan-si, "Controversy" over lawlessness such as illegal landfills. Kmaeil (2020, February 13). Retrieved December 22, 2022, from https://www.kmaeil.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=211239.

- Bereitschaft, B., Scheller, D. How Might the COVID-19 Pandemic Affect 21st Century Urban Design, Planning, and Development?. Urban Sci 2020, 4(4), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Eltarabily, S., Elgheznawy, D. Post-Pandemic Cities – The Impact of COVID-19 on Cities and Urban Design. Archit Res 2020, 10(3), 75-84. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, L., Short, J. R. The Pandemic City: Urban Issues in the Time of COVID-19. Sustainability 2021, 13(6), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Banai, R. Pandemic and the Planning of resilient cities and regions. Cities 2020, 106, 1-6. [CrossRef]

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Internet shopping users among Internet users (%) | 57.4 | 59.6 | 62.0 | 64.1 | 69.9 | 73.7 |

| Average monthly Internet shopping frequency per person (N) | 2.3 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 5.1 |

| Provinces / Metropolitan Cities | Residents | Population Density | Workers | Businesses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N/km2 | N | % | N | % | |

| Seoul Special City | 9,911,088 | 18.71 | 15,839.00 | 5,226,997 | 23.00 | 823,624 | 19.72 |

| Busan Metropolitan City | 3,438,710 | 6.49 | 4,348.90 | 1,465,433 | 6.45 | 290,357 | 6.95 |

| Daegu Metropolitan City | 2,446,144 | 4.62 | 2,728.60 | 967,934 | 4.26 | 210,944 | 5.05 |

| Incheon Metropolitan City | 3,010,476 | 5.68 | 2,765.10 | 1,092,494 | 4.81 | 206,244 | 4.94 |

| Gwangju Metropolitan City | 1,471,385 | 2.78 | 2,948.50 | 631,876 | 2.78 | 123,706 | 2.96 |

| Daejeon Metropolitan City | 1,480,777 | 2.79 | 2,758.10 | 633,418 | 2.79 | 119,628 | 2.86 |

| Ulsan Metropolitan City | 1,153,901 | 2.18 | 1,069.00 | 533,187 | 2.35 | 87,054 | 2.08 |

| Sejong Special Self-governing City | 360,907 | 0.68 | 761.3 | 125,410 | 0.55 | 18,041 | 0.43 |

| Gyeonggi Province | 13,807,158 | 26.06 | 1,325.30 | 5,302,740 | 23.34 | 934,349 | 22.37 |

| Gangwon Province | 1,560,172 | 2.94 | 90.4 | 670,247 | 2.95 | 146,815 | 3.52 |

| Chungcheongnam Province | 1,637,897 | 3.09 | 220.3 | 741,452 | 3.26 | 133,522 | 3.20 |

| Chungcheongbuk Province | 2,185,575 | 4.13 | 264 | 973,944 | 4.29 | 176,643 | 4.23 |

| Jeollanam Province | 1,835,392 | 3.46 | 223.4 | 720,052 | 3.17 | 154,082 | 3.69 |

| Jeollabuk Province | 1,884,455 | 3.56 | 144.9 | 774,294 | 3.41 | 161,883 | 3.88 |

| Gyeongsangnam Province | 2,691,891 | 5.08 | 138.9 | 1,150,047 | 5.06 | 236,807 | 5.67 |

| Gyeongsangbuk Province | 3,407,455 | 6.43 | 316.2 | 1,427,443 | 6.28 | 286,752 | 6.87 |

| Jeju Special Self-governing Province | 697,578 | 1.32 | 362.6 | 286,304 | 1.26 | 66,098 | 1.58 |

| Total | 52,980,961 | 100.00 | 516.2 | 22,723,272 | 100.00 | 4,176,549 | 100.00 |

| Zoning | Number (N) | Ratio (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residential Area | 2nd General Residential Area | 3 | 9.38 |

| 3rd General Residential Area | 11 | 34.38 | |

| Semi-Residential Area | 3 | 9.38 | |

| Commercial Area | General Commercial Area | 10 | 31.25 |

| Industrial Area | Semi-Industrial Area | 5 | 15.63 |

| Total | 32 | 100.00 | |

| Zoning | Building Usage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storage | Warehouse | Distribution Center | ||

| Residential Area | 2nd General Residential Area | Allowed | Not Allowed (Seoul: Conditional Allowance) |

Not Allowed |

| 3rd General Residential Area | Allowed | Not Allowed (Seoul: Conditional Allowance) |

Not Allowed | |

| Semi-Residential Area | Allowed | Allowed | Allowed (Seoul: Not Allowed) |

|

| Commercial Area | General Commercial Area | Allowed | Allowed | Allowed |

| Industrial Area | Semi-Industrial Area | Allowed | Allowed | Allowed |

| Attributes | Facilities | N | Mean | Std. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of older adults | B-Marts | 32 | 4,472.88 | 444.69 |

| Large discount stores | 64 | 4,214.77 | 252.87 | |

| Number of children | B-Marts | 32 | 1,870.97 | 237.38 |

| Large discount stores | 64 | 2,009.08 | 156.18 | |

| Number of bus stops | B-Marts | 32 | 21.53 | 1.45 |

| Large discount stores | 64 | 22/50 | 1.35 | |

| Number of subway stations | B-Marts | 32 | 1.06 | 0.17 |

| Large discount stores | 64 | 1.19 | 0.10 | |

| Area of parks | B-Marts | 32 | 27,339.98 | 6,580.43 |

| Large discount stores | 64 | 55,120.47 | 19,225.81 |

| Attributes | t-value | Degree of freedom | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of older adults | 0.505 | 51.632 | 0.308 |

| Number of children | -0.498 | 94 | 0.310 |

| Number of bus stops | -0.447 | 94 | 0.328 |

| Number of subway stations | -0.671 | 94 | 0.252 |

| Area of parks | -1.005 | 94 | 0.159 |

| Attributes | Number of Roads Surrounding B-Mart | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total | ||

| Number of B-Marts | 4 | 18 | 7 | 3 | 32 | |

| Ratio (%) | 12.50 | 56.25 | 21.88 | 9.38 | 100.00 | |

| Maximum Width of Road (m) | Mean | 14.25 | 28.78 | 26.86 | 30.67 | 26.72 |

| Std | 15.86 | 12.18 | 11.55 | 26.63 | 14.19 | |

| Delivery Vehicle | Car | Motorcycle | Bicycle | PM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (N) | 6 | 379 | 27 | 10 |

| Ratio (%) | 1.42 | 89.81 | 6.40 | 2.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).