Submitted:

27 April 2023

Posted:

03 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study setting

2.2. Study design and period

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.4. Sample size determination and sampling techniques

2.5. Data collection tool and procedures

2.6. Data quality assurance

2.7. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondents’ Socio-demographic characteristics

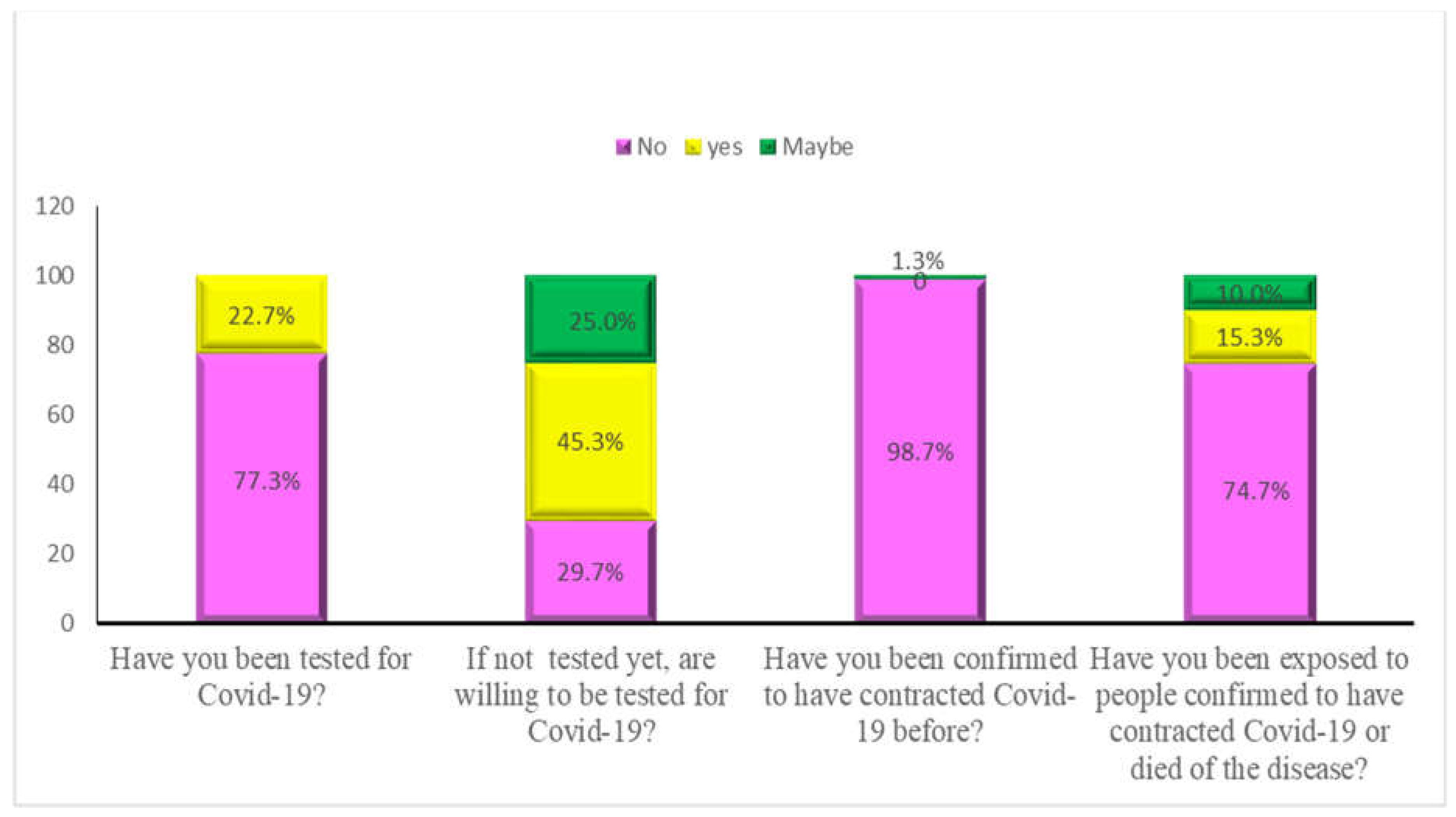

3.2. Knowledge, attitude and practices towards COVID-19 and vaccination

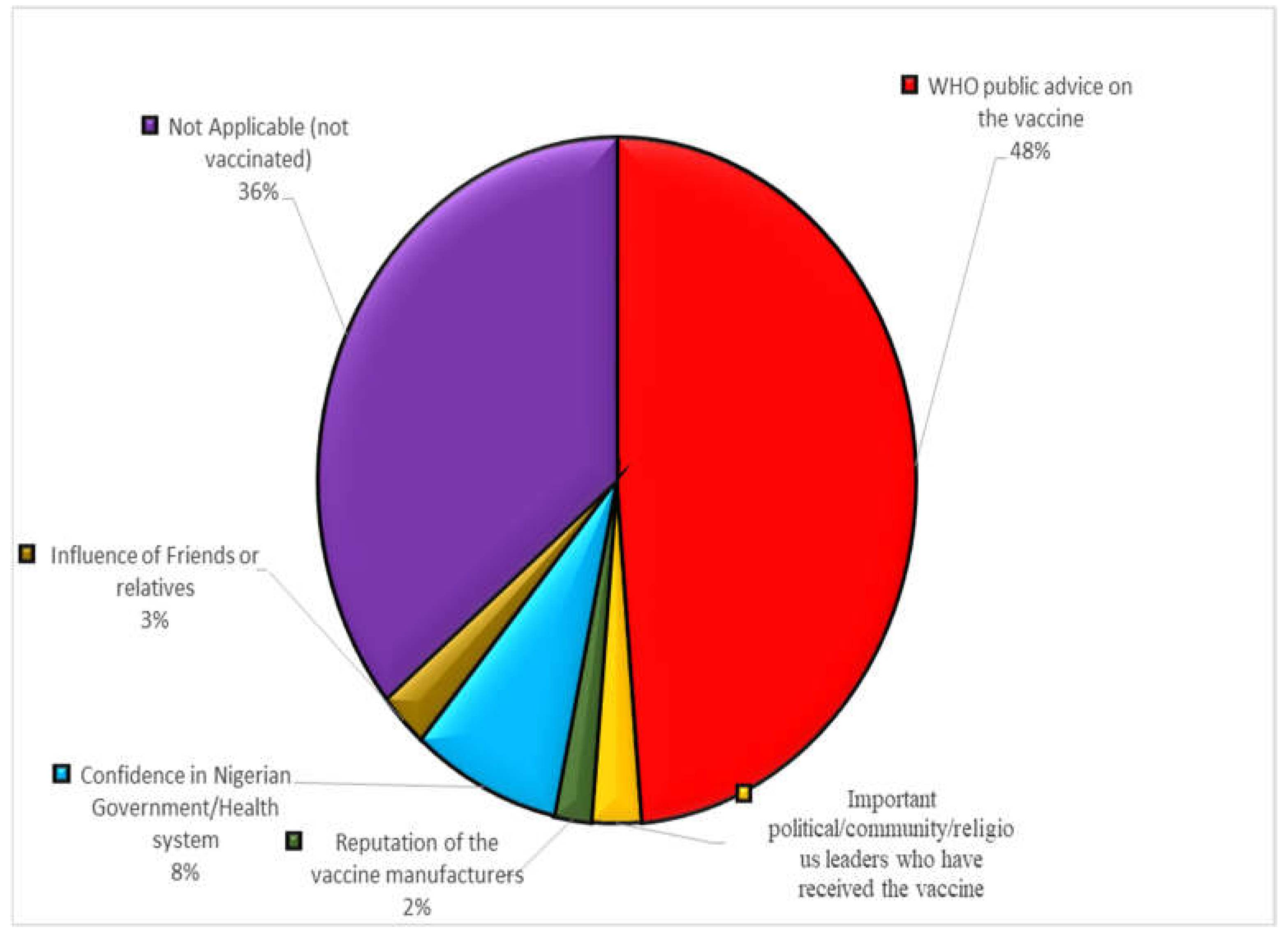

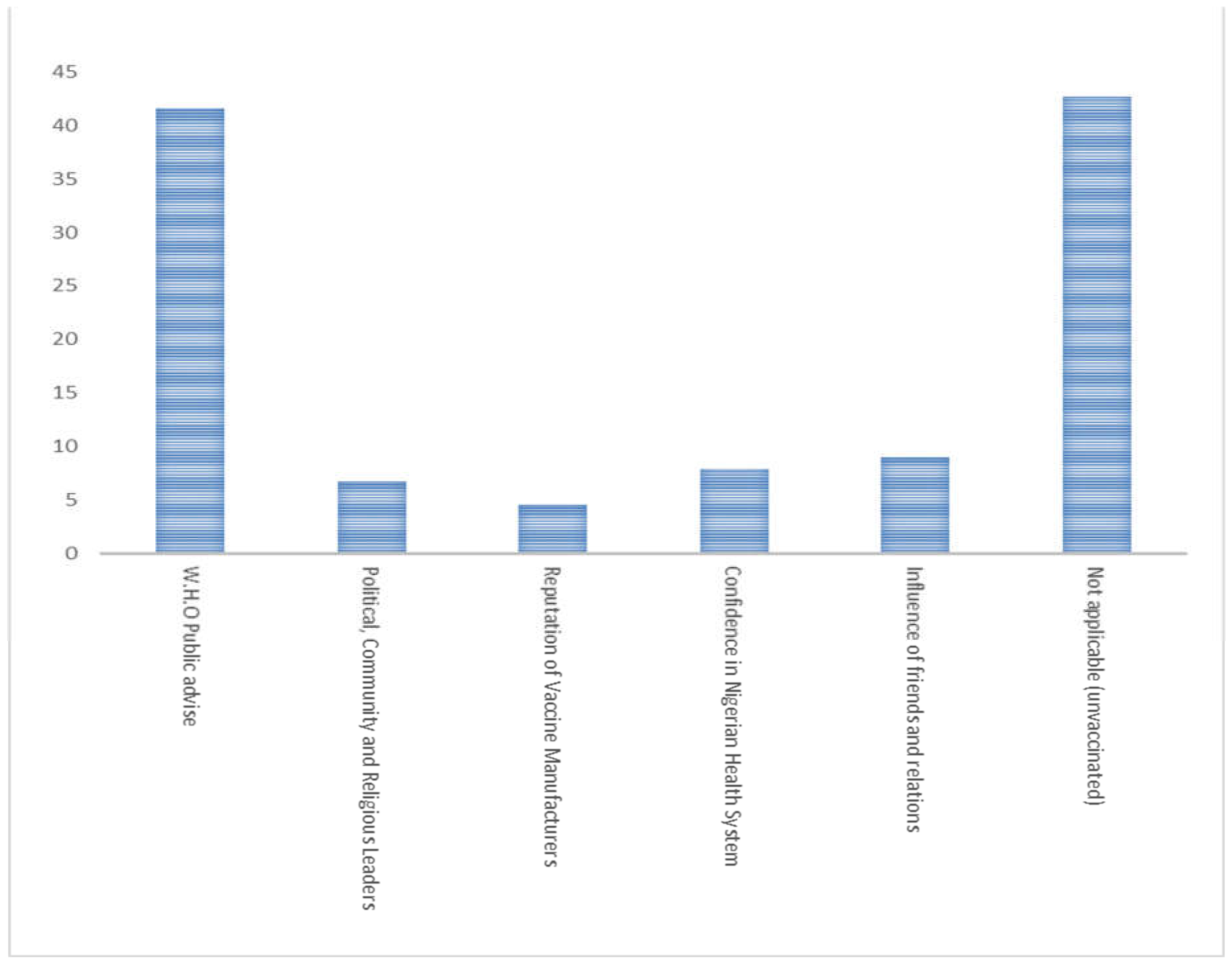

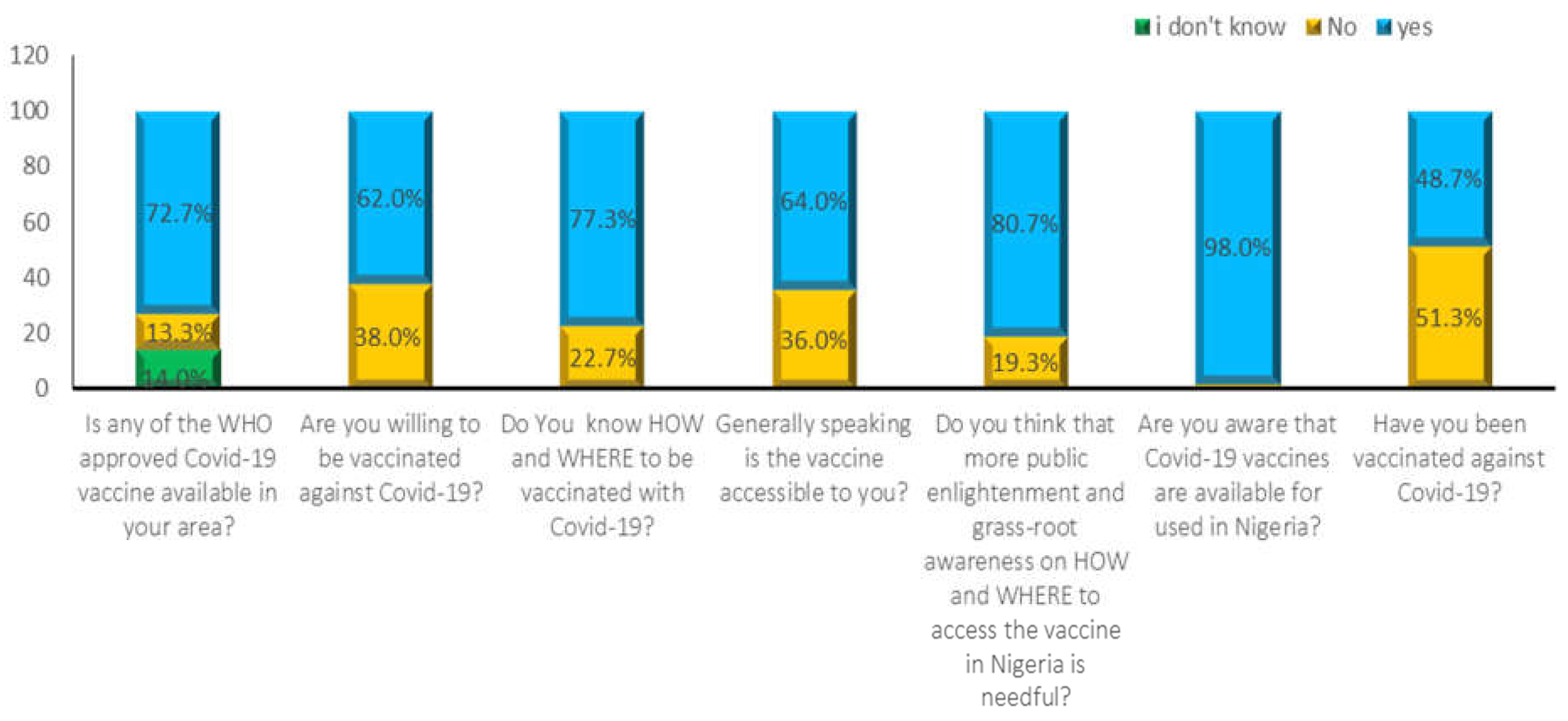

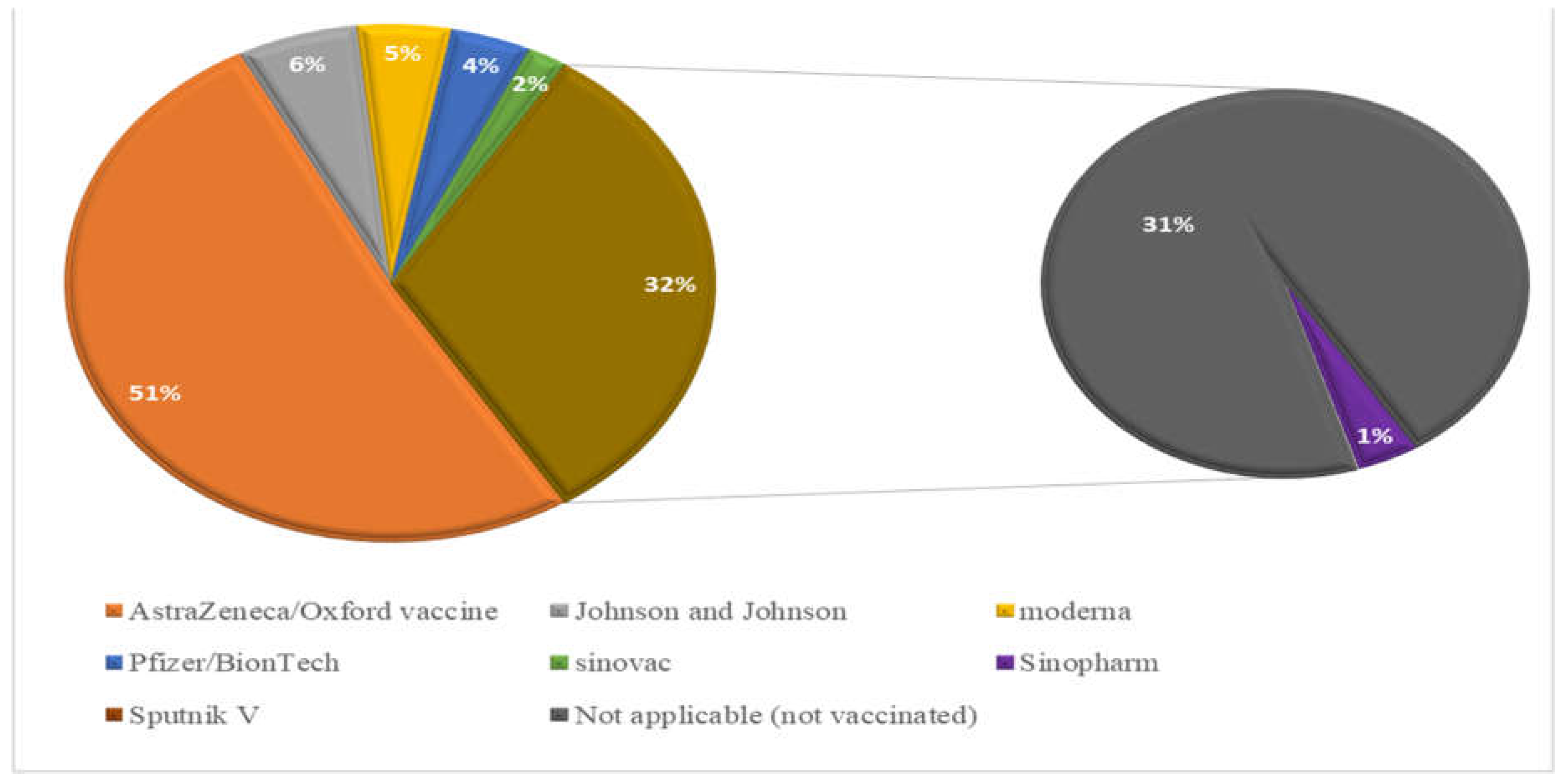

2.3. COIVD-19 Vaccine Availability, Accessibility, Acceptance, and Hesitancy

3.4. Associated factors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CDC. Basics of COVID-19. Center for disease control and prevention. 2021 [cited 2021 Jan 12]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/your-health/about-covid-19/basics-covid-19.html.

- Gbore DJ, Zakari S, Yusuf L. In silico studies of bioactive compounds from Alpinia officinarum as inhibitors of Zika virus protease. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked. 2023;38:101214. [CrossRef]

- Baker RE, Mahmud AS, Miller IF, Rajeev M, Rasambainarivo F, Rice BL, et al. Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022;20(4):193–205. [CrossRef]

- Hanna P, Issa A, Noujeim Z, Hleyhel M, Saleh N. Assessment of COVID-19 vaccines acceptance in the Lebanese population: a national cross-sectional study. J of Pharm Policy and Pract. 2022;15(1):5. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [Internet]. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. 2021 [cited 2021 Jan 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019?adgroupsurvey={adgroupsurvey}&gclid=CjwKCAjw6IiiBhAOEiwALNqncQzxt9lOFSQ_yUNnYCf4XFPxqiTsXkz3Bej34UV0IVUbEKUKmvMrzxoCznoQAvD_BwE.

- WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [Internet]. World Health Orgaanization. 2023 [cited 2023 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19.

- Fehintola JO. Challenges and Coping Strategies for Covid-19 among the Civil Populace in Southwest, Nigeria. 2021;20(1):1–13.

- Amzat J, Aminu K, Kolo VI, Akinyele AA, Ogundairo JA, Danjibo MC. Coronavirus outbreak in Nigeria: Burden and socio-medical response during the first 100 days. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020 Sep;98:218–24.

- Dan-Nwafor C, Ochu CL, Elimian K, Oladejo J, Ilori E, Umeokonkwo C, et al. Nigeria’s public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic: January to 20. Journal of Global Health. 2020;10(2):020399. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Chronic staff shortfalls stifle Africa’s health systems: WHO study [Internet]. WHO Africa. 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/chronic-staff-shortfalls-stifle-africas-health-systems-who-study.

- Azevedo MJ. The State of Health System(s) in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities. In: Historical Perspectives on the State of Health and Health Systems in Africa, Volume II [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017 [cited 2023 Apr 21]. p. 1–73. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-32564-4_1.

- Ong SWX, Young BE, Lye DC. Lack of detail in population-level data impedes analysis of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and clinical outcomes. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2021;21(9):1195–7.

- Priya Joi. Why Africa’s critically ill COVID-19 patients have the world’s highest death rates [Internet]. VaccinesWork. 2021 [cited 2023 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/why-africas-critically-ill-covid-19-patients-have-worlds-highest-death-rates?gclid=CjwKCAjw6IiiBhAOEiwALNqncZ5X-8YAR9gB5U_TH9rk8UOkEGkC1zkPfY7U-JqQnDu0-OXHKKJXShoC2TUQAvD_BwE.

- Adinde K, Emmanuel N, Onyebuchi AA, Ogbonna F. Developing the Rural Poor: A Trajectory to Curbing the Spread of COVID-19 Pandemic in Nigeria. 2021;6(3):507.

- Akor O. COVID-19: Two Years After Nigeria’s Index Case [Internet]. dailytrust. 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 21]. Available from: https://dailytrust.com/covid-19-two-years-after-nigerias-index-case/.

- Olu-Abiodun O, Abiodun O, Okafor N. COVID-19 vaccination in Nigeria: A rapid review of vaccine acceptance rate and the associated factors. Elelu N, editor. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5):e0267691.

- Alghamdi S. The role of vaccines in combating antimicrobial resistance (AMR) bacteria. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2021;28(12):7505–10. [CrossRef]

- Yarlagadda H, Patel MA, Gupta V, Bansal T, Upadhyay S, Shaheen N, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Challenges in Developing and Developed Countries. Cureus [Internet]. 2022 Apr 8 [cited 2023 Apr 21]; Available from: https://www.cureus.com/articles/92762-covid-19-vaccine-challenges-in-developing-and-developed-countries.

- Forman R, Shah S, Jeurissen P, Jit M, Mossialos E. COVID-19 vaccine challenges: What have we learned so far and what remains to be done? Health Policy. 2021;125(5):553–67.

- Teng YM, Wu KS, Wang WC, Xu D. Assessing the Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of COVID-19 among Quarantine Hotel Workers in China. Healthcare. 2021;9(6):772. [CrossRef]

- Rachlin A, Holliday CD, Murphy P, Sodha S, Wallace A. Routine Vaccination Coverage — Worldwide, 2021 [Internet]. Center for disease control and prevention. 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/mm7144a2.htm.

- Guglielmi G. Pandemic drives largest drop in childhood vaccinations in 30 years. Nature. 2022;608(7922):253–253. [CrossRef]

- Choube D, Dr. Mamta Bansal, Narang M. Covid 19 Pandemic Impact on Social Relations. 2022 Feb 15 [cited 2023 Apr 21]; Available from: https://zenodo.org/record/6085976.

- Babatope T, Ilyenkova V, Marais D. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a systematic review of barriers to the uptake of COVID-19 vaccine among adults in Nigeria. Bull Natl Res Cent. 2023;47(1):45. [CrossRef]

- Saied SM, Saied EM, Kabbash IA, Abdo SAE. Vaccine hesitancy: Beliefs and barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccination among Egyptian medical students. Journal of Medical Virology. 2021;93(7):4280–91. [CrossRef]

- Heneka MT, Golenbock D, Latz E, Morgan D, Brown R. Immediate and long-term consequences of COVID-19 infections for the development of neurological disease. Alz Res Therapy. 2020;12(1):69. [CrossRef]

- Chukwuocha UM, Emerole CO, Iwuoha GN, Dozie UW, Njoku PU, Akanazu CO, et al. Stakeholders’ hopes and concerns about the COVID-19 vaccines in Southeastern Nigeria: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2022(1):330. [CrossRef]

- Wouters OJ, Shadlen KC, Salcher-Konrad M, Pollard AJ, Larson HJ, Teerawattananon Y, et al. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. The Lancet. 2021;397(10278):1023–34. [CrossRef]

- Gudayu TW, Mengistie HT. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in sub-Saharan African countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2023;9(2):e13037. [CrossRef]

- Ajeigbe O, Arage G, Besong M, Chacha W, Desai R, Doegah P, et al. Culturally relevant COVID-19 vaccine acceptance strategies in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet Global Health. 2022;10(8):e1090–1. [CrossRef]

- Miner CA, Timothy CG, Percy K, Mashige, Osuagwu UL, Envuladu EA, et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among sub-Saharan Africans (SSA): a comparative study of residents and diasporan dwellers. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):191. [CrossRef]

- Ekowo OE, Manafa C, Isielu RC, Okoli CM, Chikodi I, Onwuasoanya AF, et al. A cross sectional regional study looking at the factors responsible for the low COVID-19 vaccination rate in Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 21];41. Available from: https://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/41/114/full. [CrossRef]

- Tadesse TA, Antheneh A, Teklu A, Teshome A, Alemayehu B, Belayneh A, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and its Reasons in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2022;32(6):1061–70. [CrossRef]

- Uzochukwu IC, Eleje GU, Nwankwo CH, Chukwuma GO, Uzuke CA, Uzochukwu CE, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among staff and students in a Nigerian tertiary educational institution. Therapeutic Advances in Infection. 2021:204993612110549. [CrossRef]

- Okai GA, Abekah-Nkrumah G. The level and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Ghana. Mossong J, editor. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(7):e0270768. [CrossRef]

- Katoto PDMC, Parker S, Coulson N, Pillay N, Cooper S, Jaca A, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in South African Local Communities: The VaxScenes Study. Vaccines. 2022;10(3):353. [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht M, Heunis C, Kigozi G. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in South Africa: Lessons for Future Pandemics. IJERPH. 2022;19(11):6694. [CrossRef]

- Njoga EO, Mshelbwala PP, Abah KO, Awoyomi OJ, Wangdi K, Pewan SB, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Determinants of Acceptance among Healthcare Workers, Academics and Tertiary Students in Nigeria. Vaccines. 2022;10(4):626. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Statement of the Independent Allocation of Vaccines Group (IAVG) of COVAX [Internet]. https://www.who.int/news/item/23-12-2021-achieving-70-covid-19-immunization-coverage-by-mid-2022. 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-12-2021-achieving-70-covid-19-immunization-coverage-by-mid-2022.

- Karlsson LC, Soveri A, Lewandowsky S, Karlsson L, Karlsson H, Nolvi S, et al. Fearing the disease or the vaccine: The case of COVID-19. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;172:110590. [CrossRef]

- Njoga EO, Mshelbwala PP, Abah KO, Awoyomi OJ, Wangdi K, Pewan SB, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Determinants of Acceptance among Healthcare Workers, Academics and Tertiary Students in Nigeria. Vaccines. 2022;10(4):626. [CrossRef]

- Sallam M, Dababseh D, Eid H, Al-Mahzoum K, Al-Haidar A, Taim D, et al. High Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Association with Conspiracy Beliefs: A Study in Jordan and Kuwait among Other Arab Countries. Vaccines. 2021;9(1):42. [CrossRef]

- Sallam M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines. 2021;9(2):160. [CrossRef]

- MacDonald NE. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4.

| Test Variable | Percentage (% | X2-Value | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test and Vaccination against COVID-19 | |||

|

Gender Male Female |

64 36 |

2.968 0.602 |

0.085 0.438 |

|

Marital Status Married Single Divorced |

42.7 56.7 0 |

0.060 2.189 |

0.741 0.335 |

|

Age 16-30 31-45 46-60 |

|||

| 30.7 60.0 |

1.766 0.579 |

0.414 0.748 |

|

| 9.3 | |||

|

Respondent’s category Academic Non-academic Student Health workers |

32.2 17.3 27.3 |

8.365 2.860 |

0.039 0.000 |

| 23.3 | |||

|

Education Secondary ND/NCE Graduate Postgraduate |

|||

| 5.3 | 1.635 | 0.651 | |

| 8.0 22.7 |

7.048 |

0.070 |

|

| 64.0 | |||

|

Religion Christians Muslims Others |

88.0 |

0.777 |

0.678 |

| 10.7 1.3 |

9.241 |

0.010 |

| S/No Questions Asked or Information Required Number of Respondents (%) |

|---|

| Reasons for non-vaccination among unvaccinated respondents (n = 150) |

| COVID-19 vaccine registration protocol is difficult 6(4.0) |

| Suspicion/doubts on safety of novel vaccines 19(12.7) |

| Herbal medicines/home remedies are effective for 2(1.3) |

| cure/ management of COVID-19 |

| COVID-19 is a hoax 5(3.3) |

| The vaccines are not available/accessible in my locality 6(4.0) |

| Influence from anti-COVID-19-vaccine movements 22(14.7) |

| Vaccination is against my religious beliefs or personal ideology 0(0) |

| Concerns about long term health/side effects 4(2.7) |

| Skepticism about the vaccine due to hasty production/roll out 48(32.0) |

| Preventive measures are enough to protect against COVID-19 3(2.0) |

| Bad feeling due to negative social media reports/rumors 35(23.3) |

| 2. Some health concerns that prevented respondents from getting vaccinated |

| Allergic reaction 37(24.7) |

| Blood clot issues among women 2(1.3) |

| New or worsening muscle/joint pains 0(0) |

| Innate immunity problems/misconceptions 16(10.7) |

| *Not applicable 95(63.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).