1. Introduction

There has been a concerning trend of church closures, particularly in areas with high concentrations of Black individuals. According to a study conducted by the Brookings Institute (2022, p.1) between 2013 and 2019, these areas have experienced the highest rates of church closures. This trend is especially worrisome as several of these closed institutions participated in the state’s COVID-19 testing initiative. The systemic underfunding of churches in the African American community has persisted for decades, indicative of broader racial inequalities and discrimination issues. As a result, Black churches receive fewer grant funds than their White counterparts. Scholars, including Chatters (2000, pp. 335–67), have noted that Black churches are crucial institutions in the African American community, providing religious guidance and essential social, economic, and political support. These churches are also vital players in community outreach initiatives. However, the closure of Black churches can significantly disrupt the African American community’s economic and social standing, as demonstrated in Chatters, Taylor, and Lincoln’s (1999, pp. 132) research. Thus, there is a pressing need to investigate the factors behind the closure of Black churches and how this trend affects the African American community.

This paper argues that the underfunding and closure of these institutions could lead to a deterioration of African American communities’ economic stability. Several key publications have explored the connection between religion and the economy in African American communities. For instance, Glaeser and others (2002) found that churches can stimulate economic growth by fostering social and economic networks. These networks, in turn, promote the development of entrepreneurship and community-based businesses. Similarly, Bradshaw and Ellison (2010, pp. 196–204) explored the relationship between religion and economic hardship, highlighting how religious beliefs and practices can support coping with financial difficulties and enhance individuals’ overall sense of financial wellness. Despite the significant implications of underfunding Black churches, there remains a paucity of research examining this phenomenon. However, recent studies have shown that the Black church’s financial struggles are complex, deep-rooted, and multifaceted and have been attributed to several factors. For instance, Pattillo-McCoy (1998, p. 767) notes that a lack of leadership succession planning, under-resourcing, and the decline in membership have all contributed to the unstable financial positions of many African American churches. Overall, further research is needed to explore the effects of religious networks on economic growth and socioeconomic outcomes in African American communities, considering the diverse denominational affiliations and religious practices present within this population.

Social capital theory posits that communities benefit from the social networks and relationships formed within them. When it comes to churches, this theory suggests that congregants not only benefit from the spiritual aspects of the church but also from the social connections fostered among members. By participating in church activities, volunteering, and forming friendships within the church community, individuals can build significant social capital to improve well-being and positive outcomes. Additionally, churches can serve as a hub for social and political issues, offering a platform for individuals to advocate for change and connect with others who share their values. Overall, the social capital theory highlights the important role that churches can play in promoting social capital and fostering community connections.

As such, this pilot study elucidates the relationship between churches and socioeconomics in African American communities. This study collected quantitative data on participants’ income levels, religious activities, and scholarship information among African Americans in different areas. Descriptive statistics analyzed the relationships among these variables. This pilot study is not meant as a comprehensive study of the intricate relationship between religion and socioeconomics in the Black community. This work’s findings and review of relevant literature can provide the groundwork for future research focusing on the determinants of economic outcomes among African Americans. A comprehensive examination of the complex interplay of religion and socioeconomic development has the potential to contribute significantly to shaping city planning and interventions that promote social equity and economic development within the African American community through the targeted incorporation of religiosity.

2. Review of Literature

This study addresses a growing concern regarding the mass closure of Black churches and its potential impact on the socioeconomic outcomes of African Americans. The church has traditionally occupied a central role in the African American community, providing support and guidance to its members and promoting social cohesion and trust among them. As such, the dwindling presence of Black churches is likely to have significant consequences for the African American community. One potential explanation for the persistent poverty gap between African Americans and other racial groups is the concept of social capital. Social capital refers to the connections and networks of relationships that individuals can leverage to obtain resources and opportunities.

The church has been shown to be a significant source of social capital for African Americans, providing them with access to valuable resources such as employment, education, and housing. However, despite its importance, the role of social capital in the Black church is not well understood. It is unclear how the Black church promotes social capital, which specific factors contribute to its effectiveness, or how it interacts with other forms of social capital in the African American community. Therefore, this literature review examines the existing research on the role of social capital in the Black church and its potential impact on the African American community. By synthesizing and analyzing the available literature, this study aims to identify the key factors that promote social capital in the Black church, assess its effectiveness in improving economic outcomes for African Americans, and explore the potential implications of the mass closure of Black churches for the African American community’s socioeconomic standing.

2.1. Theoretical Framework

The concept of social capital is present in economic and sociological traditions, with distinct yet overlapping perspectives. This may contribute to the conceptual vagueness highlighted by Durlauf and Fafchamps (2004). To understand the components of social capital and their use in economics, this article summarizes the two approaches. Social capital originates from sociology and emphasizes collectivism and structure, as opposed to the individualism and agency of economic theory. Bourdieu’s (1983, pp. 241–58) original work suggests two distinct elements of social capital: social relationships that give individuals access to the resources of other group members and the amount and quality of those resources. Paxton (1999, pp. 88–127) stresses two components, what he calls “quantitative;” the objective associations between individuals, and “qualitative;” which refers to the reciprocal and trusting associations. Empirical studies acknowledged this distinction (Gannon & Roberts 2018, pp. 899–919).

Social capital is the value that exists in social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them (Littlejohn et al. 2021, pp. 335-336). It is defined as the sum of actual or virtual resources that accrue to an individual or a group by possessing a durable network of institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition. Social capital is often divided into two main categories: bonding social capital and bridging social capital. Bonding social capital refers to the relationships among individuals who share similar characteristics, such as race, religion, or ethnicity. Such relationships can be found in neighborhoods, religious congregations, and social clubs. Bridging social capital, on the other hand, refers to the relationships among individuals who are different in some way, such as race, religion, or ethnicity (Bourdieu 1986, pp. 241–58). These relationships allow for greater exposure to diverse perspectives and can be found in workplaces, schools, and other social settings. Social capital is believed to be crucial in determining an individual’s access to resources and opportunities (Villalonga-Olives & Kawachi 2015, pp. 62–64).

2.2. Empirical Review

An empirical review of the research suggests that social capital plays an important role in the economic, political, and social well-being of African Americans. Cook (2011, pp. 1843–1930) found that African Americans used both traditional and nontraditional networks to maximize inventive output and that laws constraining social-capital formation are most negatively correlated with economically significant inventive activity. Gilbert et al. (2009, pp. 307–22) argued that social capital in the African American community had been leveraged to address health disparities directly while building political advocacy around activism on the social causes of health disparities, like racial residential segregation. Hawes (2017, pp. 393–417) found that social capital is positively associated with incarcerations, but only for African Americans. The effects of social capital appear to be conditional on the racial context, where this relationship is stronger as minority group size increases. Finally, Smith (2013, pp. 56–66) found that African Americans can potentially lessen social capital deficits through their participation on social networking sites. Overall, the studies suggest that social capital is an important factor in the lives of African Americans and that it can be leveraged to address economic, political, and social disparities.

Several key publications have analyzed the relationship between social capital and racial poverty gaps. One study by Sampson, Morenoff, and Earls (1999, p. 633) found that residential segregation - a form of institutional racism that limits minorities’ access to social resources - reduces social capital in minority communities, which in turn leads to greater poverty and disadvantage. Another study by Putnam (2001) argued that the decline of social capital in America more broadly - which he dubbed the “bowling alone” phenomenon - has disproportionately affected minorities who were already facing challenges in accessing social networks. However, the relationship between social capital and racial poverty gaps is not always clear-cut. Some scholars have questioned whether social capital is merely a proxy for other factors, such as human capital (education, skills, etc.) or structural factors (such as discrimination and policy barriers). For example, Wilson (1996) argued that the decline of inner-city work opportunities - due to deindustrialization, globalization, and other economic shifts - has contributed to a breakdown of social networks that were once based around stable jobs and institutions in urban areas. By examining how social networks can help individuals and groups overcome barriers to upward mobility and how these networks can be limited or excluded, scholars can gain important insights into the underlying social and economic dynamics of poverty and inequality.

2.3. Can Social Capital Explain Persistent Racial Poverty Gaps?

Social capital has gained attention as a potential explanatory factor for persistent racial poverty gaps in the United States. The argument is that minorities - African Americans and Latinos, in particular - have less access to social networks that offer economic opportunities, political resources, and other forms of support that contribute to upward mobility. Furthermore, they may face discrimination or bias that limits their participation in these networks, contributing to an intergenerational cycle of poverty. Quillian and Redd (2006) argue that social capital can help explain the persistent racial poverty gaps in the United States. They propose that social capital is an important factor in understanding the differences between Blacks and Whites regarding educational attainment, employment opportunities, and household income. They suggest that bonding social capital may be a barrier to economic mobility for people of color, whereas bridging social capital may facilitate it.

Quillian and Redd propose that bonding social capital can be a disadvantage for people of color because it can lead to the creation of insular communities that are less connected to the broader society. This can result in a lack of access to resources and opportunities that are available to those who are part of mainstream society. For instance, in neighborhoods with high levels of bonding social capital, people may rely on informal job networks to find employment, which can result in limited job opportunities and low wages (Quillian & Redd 2006). Moreover, Quillian and Redd suggest that bridging social capital may facilitate economic mobility for people of color. This can happen because bridging social capital enables individuals to access diverse resources and opportunities that are not available within their own networks (Quillian & Redd 2006). For example, people with diverse social networks may have greater access to information about job opportunities or education pathways that are not readily available within their communities.

2.4. How Does the Black Church Promote Social Capital?

The church has long been recognized as an important institution for fostering social capital within African American communities. This is partly due to the Church’s ability to create and maintain social networks. These networks provide mutual support, shared resources, and a sense of belonging that is especially important for African Americans, who have faced numerous obstacles to upward mobility and social integration throughout history. In fact, Michael O. Emerson and Christian Smith (2000) argue that the church’s ability to create and maintain social networks makes it one of the most crucial institutions in African American culture.

Smith (2021, p. 505) delves into the enduring and pivotal role played by the church in fostering and promoting civic engagement within the African American community. From its earliest days, the Black church served as more than a spiritual sanctuary; it also became a gathering place for those seeking refuge, community, and empowerment in the face of systemic oppression and discrimination (Smith 2021, p. 505). As Smith argues, the promotion of American civic ideals by the church continues to be an essential component of the struggle for social, economic, and political justice for Black Americans.

Other scholars have expanded on this analysis by examining specific mechanisms through which the Black church promotes social capital. For example, Lincoln and Mamiya (1990) argue that the church’s emphasis on collectivism and communalism encourages members to work together towards common goals, thereby building trust and a sense of shared identity. Similarly, Fitzgerald and Spohn (2005, pp. 1015–48) highlight the role of church involvement in promoting civic engagement and political participation among African Americans. By working together through the church, individuals can increase their political clout and improve their ability to effect change in their communities.

Brown & Brown (2003, pp. 617–41) explores the relationship between African American political activism and church-based social capital resources. Brown & Brown examines how religion can be essential in shaping African American political activism and influencing their social capital. He starts by drawing attention to the historical and contemporary context of African American political activism, dating back to the Civil Rights Movement, fueled by a desire for social justice and equality. Brown & Brown argues that African American leaders during these movements played a crucial role in utilizing resources provided by their religious institutions, such as churches, in mobilizing and empowering their communities. Further, he contends that the church is an important source of social capital for African Americans because it provides a platform for collective action, social support, and community development. Brown & Brown elaborates on the concept of social capital as a valuable resource acquired when people form networks and relationships that can lead to mutual benefits. He proposes that African Americans who actively engage with their churches and communities have access to valuable social capital resources to aid in political activism.

Brown & Brown cites numerous studies that corroborate his views and provide empirical evidence to support his thesis. For instance, Brown & Brown suggests that the relationships formed through religious networks foster a sense of obligation and reciprocity, facilitating collective action. The article also provides several examples of African American churches, such as the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, demonstrating the potential of church-based social capital to facilitate political activism. Brown & Brown concludes that the church is an essential component of African American political activism in fostering social capital resources. However, he also acknowledges the potential limitations of relying solely on church-based social capital resources (Brown & Brown 2003, pp. 617–41). The literature proposes that African American political activists should seek to engage with other sources of social capital resources beyond religious institutions to broaden their support base and achieve their goals.

By exploring the role of churches in providing resources, these authors shed light on the importance of faith-based institutions in empowering and mobilizing African American leaders during times of social and political unrest. From the Civil Rights Movement to present-day movements, the church has consistently served as a cornerstone for African American political activism, providing a space for community-building, organization, and advocacy. The authors argue that understanding the relationship between the church and African American political activism is crucial for contextualizing the persistent presence of religion and religious institutions in these communities today. Overall, these key publications demonstrate the multifaceted ways the church contributes to developing and maintaining social capital in African American communities. By providing social networks, fostering collective identities, and promoting civic engagement, the church plays a vital role in building and sustaining the social fabric of these communities.

2.5. What Are the Implications of the Mass Closure of Black Churches?

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted every aspect of our lives and has posed some unique challenges. For African Americans, the pandemic has only exacerbated the deep-rooted issue of racism that existed long before the virus. The study conducted by DeSouza, Parker, and Spearman-McCarthy (2020, pp. 7–11) sheds light on the impact of church closures on the mental health of African Americans who rely on their faith to cope with racism. The study is a poignant reminder of how the pandemic has disproportionately affected marginalized communities. It highlights the need for more comprehensive mental health resources that cater to those who face systemic racism.

DeSouza et al. have pointed out the disproportionate impact that this virus has had on this community, including higher mortality rates and a greater likelihood of experiencing negative economic and social impacts. One challenge that has emerged is the closure of many churches, which plays a vital role in African American culture (DeSouza et al. 2020, pp. 7–11). Furthermore, DeSouza et al. note that research has consistently found a positive association between religious practices and mental health outcomes, with religious involvement often being linked to lower levels of anxiety and depression, among other benefits. However, they also highlight that religion can stress some individuals, particularly when they feel disconnected from their faith community.

In discussing the impact of COVID-19 on mental health, the authors note that the pandemic has been associated with increased stress, anxiety, and depression among the general population (DeSouza et al. 2020, pp. 7–11). They draw attention to the fact that African Americans have been particularly hard hit by COVID-19-related stressors, which may exacerbate pre-existing mental health conditions. Finally, the authors explore how African Americans cope with racism. While many individuals use religious coping strategies to deal with racial discrimination, others may turn to social support networks, activism, or other resistance means. However, with church closures, many African Americans are left without these vital coping mechanisms, which can negatively affect their mental health.

The present study investigates the potential relationship between religious engagement and socioeconomic status among African Americans. Specifically, the study addresses the research questions: Do African Americans believe their religious affiliation has contributed to their socioeconomic progress? Does active involvement in religious activities predict higher annual income for African Americans? Is there a significant relationship between the frequency of religious participation and the likelihood of receiving scholarship or grant funding from religious organizations for African American students?

3. Results

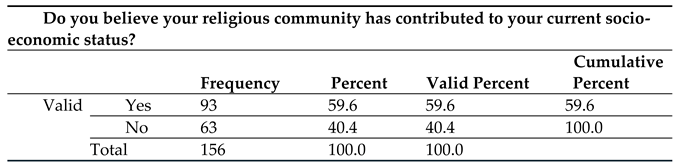

Table 1 provides the frequency distribution results to the question: “Do you believe your religious affiliation has contributed to your current socioeconomic status?” The most frequently observed category was Yes (n = 93, 59.62%), indicating that approximately 60% of the sample population attribute their success to the support of their faith-based community. The hypothesis, “African Americans with religious affiliation believe their faith has contributed to their socioeconomic progress,” was supported. This finding provides preliminary insight into the connection between religious engagement and socioeconomic status among African Americans.

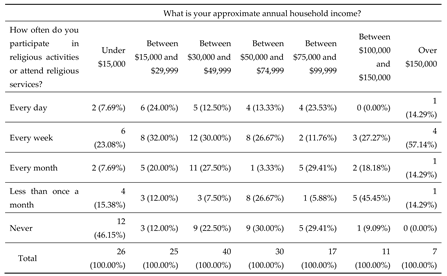

The hypothesis that a positive relationship exists between active involvement in religious activities and higher annual income is partially supported by the finding that individuals who earned a higher income reported more frequent participation in weekly religious services or activities. However, the most common response from individuals earning between

$15,000 to

$29,999 was "every week," which is a surprising finding. This suggests that income level may not be the only factor at play when it comes to religious involvement. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for participating in religious activities split by annual household income. Frequencies and percentages are presented in

Table 2. The most frequently observed category of “participating in religious services or activities” within the Under

$15,000 category of Annual Income was Never (n = 12, 46.15%). The most frequently observed category of Participating in religious services or activities within the Between

$15,000 and

$29,999 category of Annual Income was Every week (n = 8, 32.00%). The most frequently observed category of Participating in religious services or activities within the Between

$30,000 and

$49,999 category of Annual Income was Every week (n = 12, 30.00%). The most frequently observed category of Participating in religious services or activities within the Between

$50,000 and

$74,999 category of Annual Income was Never (n = 9, 30.00%). The most frequently observed categories of Participating in religious services or activities within the Between

$75,000 and

$99,999 category of Annual Income were Every month and Never (n = 5, 29.41%). The most frequently observed category of Participating in religious services or activities within the Between

$100,000 and

$150,000 category of Annual Income was Less than once a month (n = 5, 45.45%). The most frequently observed category of Participating in religious services or activities within the Over

$150,000 category of Annual Income was Every week (n = 4, 57.14%).

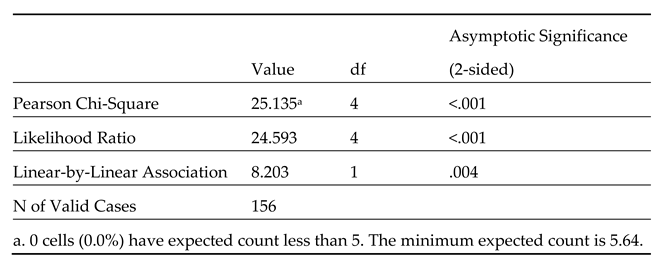

The hypothesis that there is a significant relationship between the frequency of religious participation and the likelihood of receiving scholarship or grant funding from religious organizations for African American students is supported. The findings of a chi-square test of independence revealed a significant relationship between the frequency of religious participation and the likelihood of receiving a scholarship or grant funding from religious organizations. The chi-square test examined whether Q7 (“How often do you participate in religious activities or attend religious services?”) and Q8 (“Have you ever received a scholarship or grant to fund your education from a religious organization?”) were independent. There were five levels in Q7: Every day, Every week, Every month, Less than once a month, and Never. There were two levels in Q8: Yes and No.

Table 3 presents the results of the Chi-square test. The assumption of adequate cell size was assessed, which requires all cells to have expected values greater than zero and 80% of cells to have expected values of at least five (McHugh 2013, 143–49). All cells had expected values greater than zero, indicating that the first condition was met. 100.00% of the cells had expected frequencies of at least five, indicating the second condition was met.

The Chi-square test results were significant based on an alpha value of .05, χ2(4) = 25.13, p < .001, suggesting that Q7 and Q8 are related.

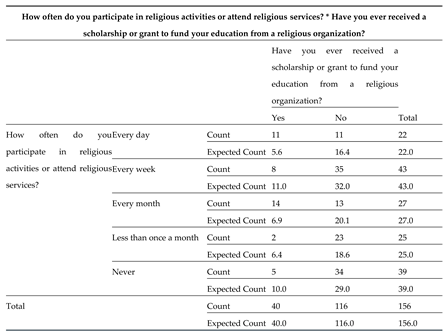

Table 4 presents the crosstabulation of the Chi-square test. The significant results showed a clear relationship between Q7 and Q8, with an alpha value of .001 and a Chi-square value of 25.13. The following level combinations had observed values that were greater than their expected values: Q7 (Every day): Q8 (Yes), Q7 (Every month): Q8 (Yes), Q7 (Every week): Q8 (No), Q7 (Less than once a month): Q8 (No), and Q7 (Never): Q8 (No). The following level combinations had observed values that were less than their expected values: Q7 (Every week): Q8 (Yes), Q7 (Less than once a month): Q8 (Yes), Q7 (Never): Q8 (Yes), Q7 (Every day): Q8 (No), and Q7 (Every month): Q8 (No). This finding suggests that religious participation frequency and funding for education are linked, providing valuable insights for further discussion and explorations.

4. Discussion

Table 1 presents intriguing results regarding whether one’s religious community has played a role in their socioeconomic status. Notably, the most common answer was in the affirmative, with 60% of the sample population responding with “Yes.” This suggests that individuals who actively participate in religious activities may perceive their spiritual communities as contributing to their success. Of particular interest is the breakdown of responses according to household income, which may reveal further insights into how religious affiliation and socioeconomic status intersect.

It is interesting to see how income plays a role in religious participation, as revealed in

Table 2. For those earning under

$15,000, it is not surprising to see that “never” is the most common response. However, it is fascinating to note that for those earning between

$15,000 to

$29,999, the most common reply was “every week.” This suggests that people in lower income categories might seek refuge in religion more than we assume. On the other hand, for people earning

$50,000 to

$75,000, “never” seems to be the prevalent response, perhaps indicating a shift towards secularism or a detachment from traditional religious practices. Nonetheless, the data shows that religion still holds an important place in many people’s lives. These findings underscore the importance of faith-based organizations as providers of social support and resources, highlighting the potential value of such communities beyond merely spiritual guidance.

The finding that engaging in religious activities was positively associated with the likelihood of receiving a scholarship from a religious organization further underscores the importance of active involvement in faith communities for African Americans seeking to improve their socioeconomic status. These results align with previous studies that have found that religion plays a crucial role in the lives of African Americans, providing them with social support and cultural resources that promote resilience and success. Additionally, this study provides insights into the influence of religious involvement on academic pursuits. It recognizes the potential motivational benefits of religious experiences on academic achievements. Moreover, further research is needed to highlight the importance of considering religiosity as a potential predictor of scholarship receipt. Religious organizations can use such information better to understand the needs and interests of their constituents and develop targeted scholarship programs that cater to different levels of religiosity.

However, it should be noted that the study has two limitations that need to be addressed. Firstly, the pilot sample size was relatively small, which constrains the generalizability of the findings. Secondly, the survey was designed to capture only quantitative data on education outcomes and income levels. As such, it did not account for important contextual and socioeconomic factors that may influence the relationship between denominational affiliations and education outcomes. While these findings may be limited due to the pilot study’s sample size, they raise important questions about the intersection of faith and societal structures. How much of an impact do these beliefs have on our economic circumstances? Furthermore, how might economic outcomes shape our religious beliefs and practices? Therefore, further research with a larger sample of African Americans is warranted to elucidate the associations between religious affiliations, education outcomes, and income.

5. Methodology

The methodology employed in this study involved collecting data from a randomized sample of 156 participants, while limited in size, provided a preliminary basis for understanding the relationship between the variables of interest. Data collected from the survey questionnaire were analyzed using statistical techniques and IBM SPSS software to identify patterns and trends in the responses given. These results were discussed in detail, drawing upon an extensive literature review and theory to provide further insight and explanation.

To investigate the perceived contribution of religious communities to the socioeconomic status of African Americans, the primary survey question was, “Do you believe your religious community has contributed to your current socioeconomic status?” Respondents were asked to respond “Yes” or “No.”

Table 1 analyzed the survey data using descriptive statistics, including frequency distributions, to explore the relationship between religious affiliation and perceptions of community support. In analyzing the data, frequencies and percentages were calculated for each response category, with the results in

Table 2. Specifically, frequencies and percentages were calculated for the survey question that asked participants how often they engage in religious activities or attend religious services. The frequencies and percentages were calculated separately for each income bracket, which allowed for an analysis of the relationship between household income and religious participation.

To investigate the relationship between Q7 and Q8, which pertained to the frequency of religious activities/attendance and the receipt of scholarships/grants from a religious organization, a chi-square test of independence was used to determine whether there was a significant association between these variables. The test was chosen because it is an appropriate statistical measure for assessing the degree of association between categorical variables. Participants were asked to respond to the questions (Q7) “How often do you participate in religious activities or attend religious services?” and (Q8) “Have you ever received a scholarship or grant to fund your education from a religious organization?” Q7 was measured on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “Every day” to “Never,” while Q8 was measured as a dichotomous variable with two response options: “Yes” or “No.”

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this pilot study sheds light on the important relationship between religion and socioeconomics in African American communities. The findings demonstrate a strong connection between religious engagement and positive socioeconomic outcomes, including higher annual incomes and increased access to education funding. Social capital plays a critical role in explaining the persistent racial poverty gaps in the United States. Bonding social capital, which can create insular communities, may act as a barrier to economic mobility for people of color, whereas bridging social capital, which can facilitate access to diverse resources and opportunities, may promote it. Ultimately, the literature suggests that the church plays a vital role in creating and sustaining social capital in the African American community. By providing a space for community members to come together, share experiences, and build relationships, the church contributes to the economic and social well-being of African Americans.

As society continues to grapple with issues of inequality and social disconnection, understanding the role of social capital and the church will be increasingly important for policymakers and researchers designing policies and programs that aim to reduce poverty and enhance economic mobility for people of color. This research serves as a starting point for future studies exploring the complex relationship between religion and socioeconomic development in minority communities. It provides valuable insights into the potential benefits of incorporating religiosity into interventions and city planning aimed at promoting social equity and economic development within the African American community. A comprehensive investigation focusing on the determinants of economic outcomes among African Americans can build upon these findings to develop targeted interventions that maximize the benefits of religious engagement for individuals in this community. In closing, this pilot study highlights the valuable role that churches can play in promoting social capital and fostering community connections.

Funding

This project received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. This pilot study project required human subjects review as human subjects are involved. Additionally, surveys or other data collection efforts for the program or institutional improvement underwent review. The research follows ethical guidelines for the protection of human subjects. To that end, the researcher employing human subjects completed the CITI (Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative). This training and other guidelines include information on developing appropriate introductory letters and utilizing other informed consent language.

References

-

Bourdieu, Pierre; Greenwood: (1986). The Forms of Capital in Richardson, John G., ed., Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, New York; pp. 241–58.

- Bradshaw, Matt, and Christopher G. Ellison. “Financial Hardship and Psychological Distress: Exploring the Buffering Effects of Religion.” Social Science & Medicine 71, no. 1 (2010): 196–204. [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. K., and R. E. Brown. “Faith and Works: Church-Based Social Capital Resources and African American Political Activism.” Social Forces 82, no. 2 (2003): 617–41. [CrossRef]

- Chatters, Linda M. “Religion and Health: Public Health Research and Practice.” Annual Review of Public Health 21, no. 1 (2000): 335–67. [CrossRef]

- Chatters, Linda M. , Robert Joseph Taylor, and Karen D. Lincoln. “African American Religious Participation: A Multi-Sample Comparison.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 38, no. 1 (1999): 132. [CrossRef]

- Cook, Lisa D. “Inventing Social Capital: Evidence from African American Inventors, 1843–1930.” Explorations in Economic History 48, no. 4 (2011): 507–18. [CrossRef]

- DeSouza, Flavia, Carmen Black Parker, E. Vanessa Spearman-McCarthy, Gina Newsome Duncan, and Reverend Maria Black. “Coping with Racism: A Perspective of Covid-19 Church Closures on the Mental Health of African Americans.” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 8, no. 1 (2020): 7–11. [CrossRef]

- Durlauf, Steven, and Marcel Fafchamps. “Social Capital,” 2004. [CrossRef]

-

Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America; Oxford University Press, 2001: New York, NY.

- Fitzgerald, S. T., and R. E. Spohn. “Pulpits and Platforms: The Role of the Church in Determining Protest among Black Americans.” Social Forces 84, no. 2 (2005): 1015–48. [CrossRef]

- Gannon, Brenda, and Jennifer Roberts. “Social Capital: Exploring the Theory and Empirical Divide.” Empirical Economics 58, no. 3 (2018): 899–919. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Keon, and Lorraine Dean. “Social Capital, Social Policy, and Health Disparities: A Legacy of Political Advocacy in African-American Communities.” Global Perspectives on Social Capital and Health, 2013, 307–22. [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, Edward, David Laibson, Jose Scheinkman, and Christine Soutter. “What Is Social Capital? the Determinants of Trust and Trustworthiness,” 1999. [CrossRef]

- Hawes, Daniel P. “Social Capital, Racial Context, and Incarcerations in the American States.” State Politics & Policy Quarterly 17, no. 4 (2017): 393–417. [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Eric C. The Black Muslims in America, Beacon Press, 1961.

-

Theories of Human Communication; Waveland Press, Inc., 2021l: Long Grove, IL; pp. 335–336.

- McHugh, Mary L. “The Chi-Square Test of Independence.” Biochemia Medica, 2013, 143–49. [CrossRef]

- Pattillo-McCoy, Mary. “Church Culture as a Strategy of Action in the Black Community.” American Sociological Review 63, no. 6 (1998): 767. [CrossRef]

- Paxton, Pamela. “Is Social Capital Declining in the United States? A Multiple Indicator Assessment.” American Journal of Sociology 105, no. 1 (1999): 88–127. [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert D. “Bowling Alone.” Proceedings of the 2000 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Quillian, Lincoln, and Rozlyn Redd. “Can Social Capital Explain Persistent Racial Poverty Gaps?” National Poverty Center Working Paper Series Index. National Poverty Center, 2006. https://npc.umich.edu/publications/workingpaper06/paper12/working_paper06-12.pdf.

- Ransome, Yusuf, Insang Song, Linh Pham, and Camille Busette. “Churches Are Closing in Predominantly Black Communities.” Brookings. The Brookings Institution, May 4, 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/how-we-rise/2022/05/03/churches-are-closing-in-predominantly-black-communities-why-public-health-officials-should-be-concerned/.

- Sampson, Robert J. , Jeffrey D. Morenoff, and Felton Earls. “Beyond Social Capital: Spatial Dynamics of Collective Efficacy for Children.” American Sociological Review 64, no. 5 (1999): 633. [CrossRef]

- Shrider, Emily, Melissa Kollar, Frances Chen, and Jessica Semega. Rep. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020. US Census Bureau: US Department of Commerce, 2021.

- Smith, Danielle. “African Americans and Network Disadvantage: Enhancing Social Capital through Participation on Social Networking Sites.” Future Internet 5, no. 1 (2013): 56–66. [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. Drew. “The Diminished Public, and Black Christian Promotion of American Civic Ideals.” Religions 12, no. 7 (2021): 505. [CrossRef]

- Taffe, Michael A, and Nicholas W Gilpin. “Racial Inequity in Grant Funding from the US National Institutes of Health.” eLife 10 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Villalonga-Olives, Ester, and Ichiro Kawachi. “The Measurement of Social Capital.” Gaceta Sanitaria 29, no. 1 (2015): 62–64. [CrossRef]

-

Wilson, William Julius; The World of the New Urban Poor: When Work Disappears.

Table 1.

Frequency Distribution.

Table 1.

Frequency Distribution.

Table 2.

Frequency Table.

Table 2.

Frequency Table.

Table 3.

Chi-square Test of Independence.

Table 3.

Chi-square Test of Independence.

Table 4.

Chi-square Test Crosstabulation.

Table 4.

Chi-square Test Crosstabulation.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).