Submitted:

03 May 2023

Posted:

04 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Perceived risk

2.2. Health crises and perceived risk

3. Methodology

3.1. The Delphi technique and MCDA

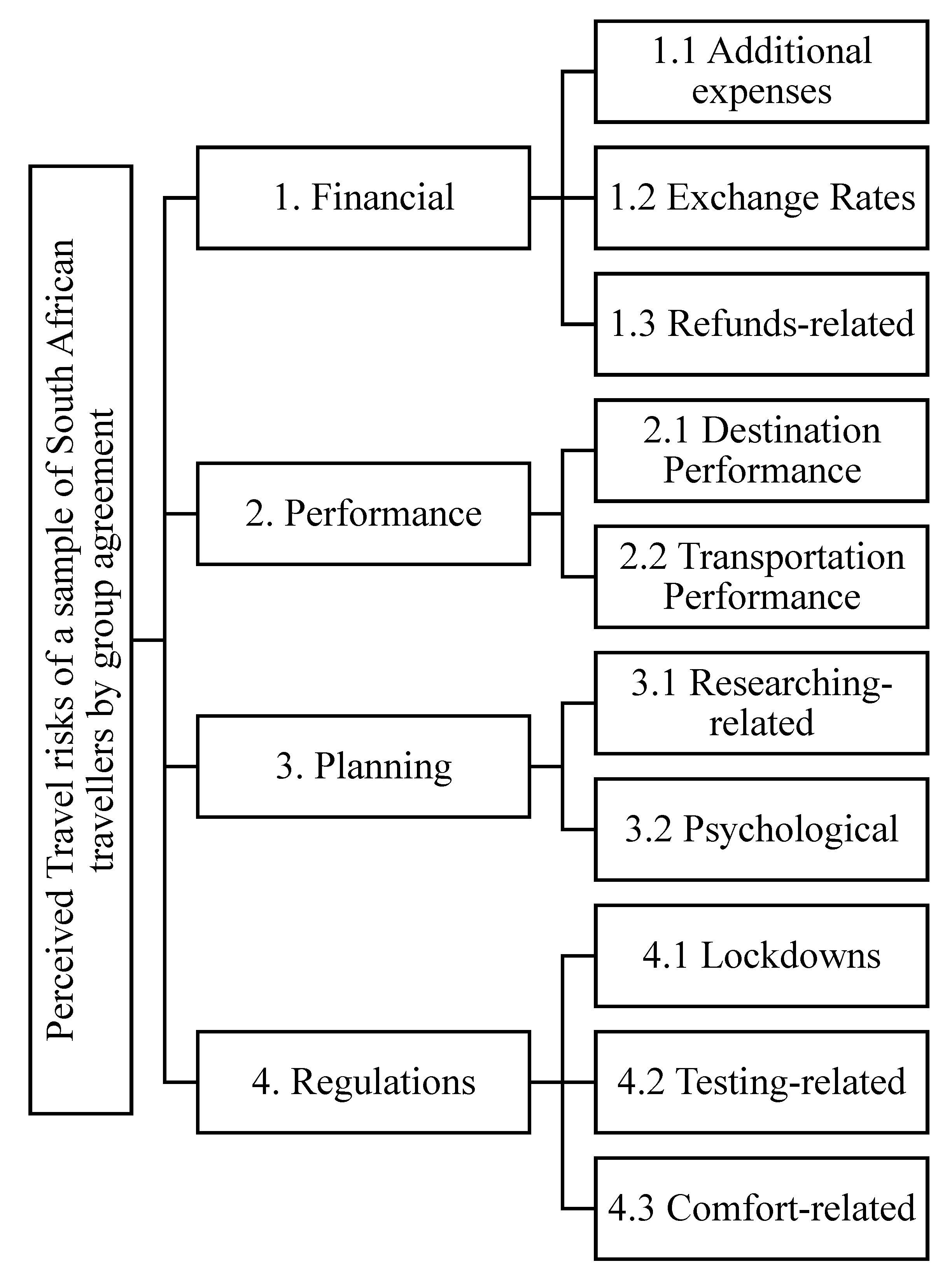

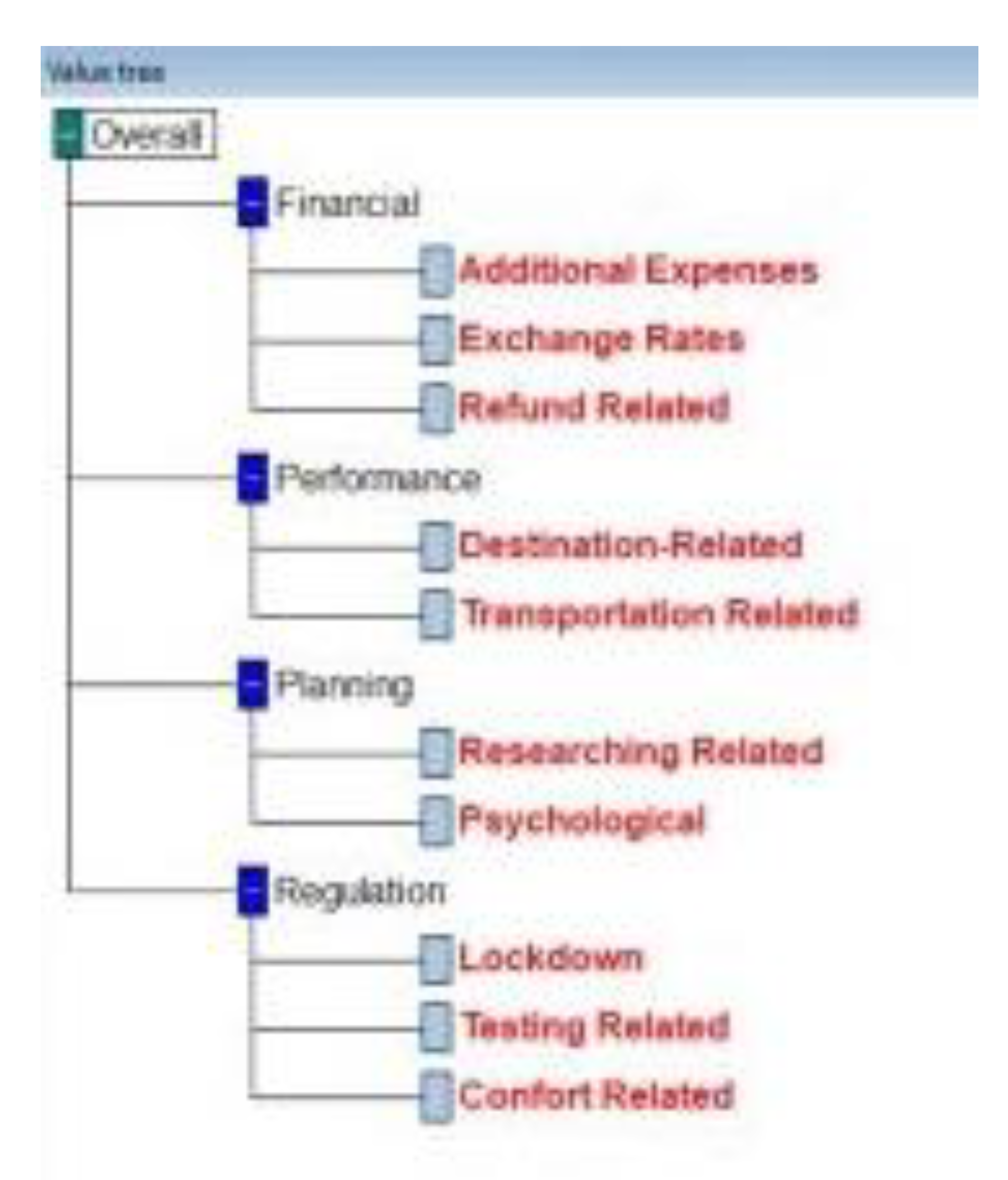

3.2. The structuring phase: The Delphi technique

3.3. The evaluation phase

3.4. The prioritization phase

4. Case Study

4.1. South Africa

4.2. Participants' general characteristics

4.3. Positive coefficients

4.4. Rounds

4.4.2. Round 2

4.4.3. Round 3

4.4.4. Round 4

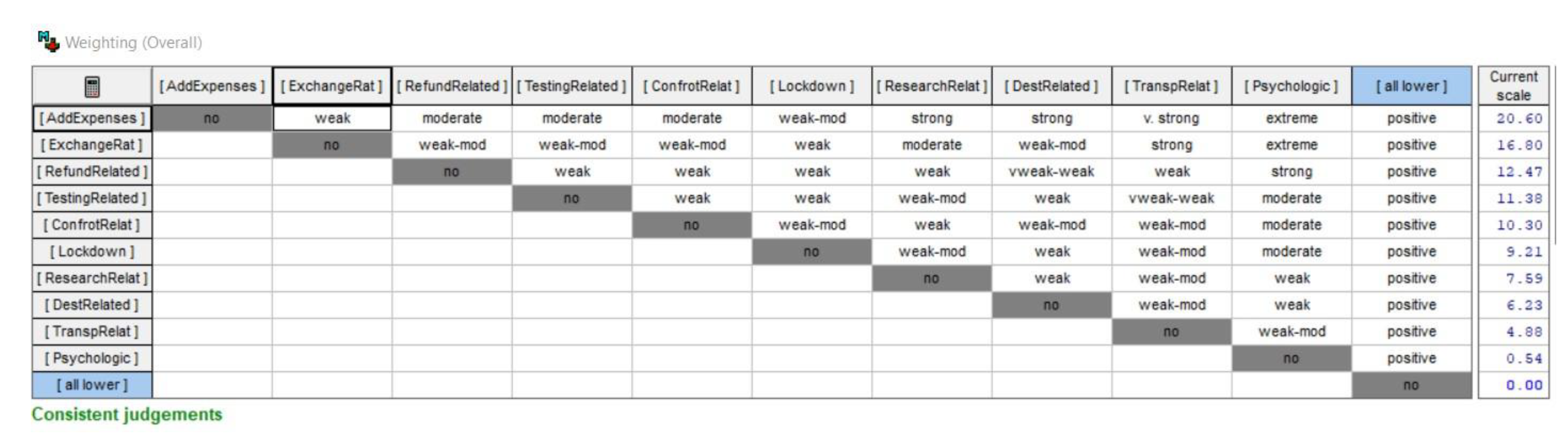

4.5. MACBETH

4.6. Testing the model

5. Discussion and concluding remarks

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- An, M. , Lee, C., & Noh, Y. (2010). Risk factors at the travel destination: Their impact on air travel satisfaction and repurchase intention. Service Business, 4(2), 155–166. [CrossRef]

- Arndt, C. , Gabriel, S., & Robinson, S. (2020). Assessing the toll of Covid-19 lockdown measures on the South African economy. [CrossRef]

- Bana e Costa, C. A., De Corte, J., & Vansnick, J. (2012). Macbeth. International Journal of Information Technology & Decision Making, 11(02), 359–387. [CrossRef]

- Bana e Costa, C. A., & Chagas, M. P. (2004). A career choice problem: An example of how to use Macbeth to build a quantitative value model based on qualitative value judgments. European Journal of Operational Research, 153(2), 323–331. [CrossRef]

- Bana e Costa, C. A., Fernandes, T. G., & Correia, P. V. (2006). Prioritisation of public investments in social infrastructures using multicriteria value analysis and decision conferencing: A case study. International Transactions in Operational Research, 13(4), 279–297. [CrossRef]

- Bana e Costa, C. A., Lopes, D. F., & Oliveira, M. D. (2014). Improving risk matrices using the Macbeth approach for multicriteria value measurement. Proceedings of Maintenance Performance Measurement and Management (MPMM) Conference 2014, 189–195. [CrossRef]

- Bana e Costa, C. A., Lourenço, J. C., Oliveira, M. D., & Bana e Costa, J. C. (2013). A socio-technical approach for Group Decision Support in Public Strategic Planning: The Pernambuco PPA case. Group Decision and Negotiation, 23(1), 5–29. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R. Bauer, R. (1960). Consumer Behaviour as Risk-taking. In R. Hancock (Ed.), Dynamic Marketing for a Changing World (pp. 389–398). Chicago, Illinois; American Marketing Association.

- Beiderbeck, D. , Frevel, N., von der Gracht, H. A., Schmidt, S. L., & Schweitzer, V. M. (2021). Preparing, conducting, and analyzing Delphi Surveys: Cross-disciplinary practices, New Directions, and advancements. MethodsX, 8, 101401. [CrossRef]

- Boksberger, P. E., Bieger, T., & Laesser, C. (2007). Multidimensional analysis of perceived risk in commercial air travel. Journal of Air Transport Management, 13(2), 90–96. [CrossRef]

- Botti, L. , & Peypoch, N. (2013). Multicriteria electre method and destination competitiveness. Tourism Management Perspectives, 6, 108–113. [CrossRef]

- Boulkedid, R. , Abdoul, H., Loustau, M., Sibony, O., & Alberti, C. (2011). Using and reporting the Delphi Method for Selecting Healthcare Quality Indicators: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE, 6(6). [CrossRef]

- Bratić, M. , Radivojević, A., Stojiljković, N., Simović, O., Juvan, E., Lesjak, M., & Podovšovnik, E. (2021). Should I stay or should I go? tourists' Covid-19 risk perception and vacation behavior shift. Sustainability, 13(6), 3573. [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. (1998). Strategic use of information technologies in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 19(5), 409–421. [CrossRef]

- Burke, R; Planning and Control Techniques (3rd ed: (2000). Project Management.

- Bush, T; //pestleanalysis: (2020, November 10). Pest analysis of coronavirus: Pandemic's 9 impacts to world. PESTLE Analysis. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from https.

- Carayannis, E. G., Ferreira, F. A. F., Bento, P., Ferreira, J. J. M., Jalali, M. S., & Fernandes, B. M. Q. (2018). Developing a socio-technical evaluation index for Tourist Destination Competitiveness using cognitive mapping and MCDA. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 131, 147–158. [CrossRef]

- Casidy, R. , & Wymer, W. (2016). A risk worth taking: Perceived risk as moderator of satisfaction, loyalty, and willingness-to-pay premium price. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 32, 189–197. [CrossRef]

- Chebli, A. , & Foued, B. S. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 on tourist consumption behaviour : A perspective article. Journal of Tourism Management Research, 7(2), 196–207. [CrossRef]

- Chew, E. Y., & Jahari, S. A. (2014). Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tourism Management, 40, 382–393. [CrossRef]

- Chien, P. M., Sharifpour, M., Ritchie, B. W., & Watson, B. (2017). Travelers' health risk perceptions and protective behavior: A psychological approach. Journal of Travel Research, 56(6), 744–759. [CrossRef]

- Chinazzi, M. , Davis, J. T., Ajelli, M., Gioannini, C., Litvinova, M., Merler, S., Pastore y Piontti, A., Mu, K., Rossi, L., Sun, K., Viboud, C., Xiong, X., Yu, H., Halloran, M. E., Longini, I. M., & Vespignani, A. (2020). The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak. Science, 368(6489), 395–400. [CrossRef]

- Conchar, M. P. (2004). An integrated framework for the conceptualization of consumers' perceived-risk processing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(4), 418–436. [CrossRef]

- Cracolici, M. F., & Nijkamp, P. (2008). The attractiveness and competitiveness of tourist destinations: A Study of Southern Italian regions. Tourism Management, 30(3), 336–344. [CrossRef]

- Cui, F. , Liu, Y., Chang, Y., Duan, J., & Li, J. (2016). An overview of tourism risk perception. Natural Hazards, 82(1), 643–658. [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, S. Cunliffe, S. (2002). Forecasting Risks in the Tourism Industry using the Delphi Technique (thesis).

- Dolnicar, S. (2005). Understanding barriers to leisure travel: Tourist fears as a marketing basis. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 11(3), 197–208. [CrossRef]

- El Gibari, S. , Gómez, T., & Ruiz, F. (2018). Building composite indicators using multicriteria methods: A Review. Journal of Business Economics, 89(1), 1–24. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, (E; ECDC: C. D. P. C. (2015). (tech.). Best practices in ranking emerging infectious disease threats (pp. 1–38). Stockholm, Sweden.

- Floyd, M. F. Floyd, M. F., Gibson, H., Pennington-Gray, L., & Thapa, B. (2004). The effect of risk perceptions on intentions to travel in the aftermath of , 2001. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 15(2-3), 19–38. 11 September. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, Â. , Santana, P., Oliveira, M. D., Almendra, R., Bana e Costa, J. C., & Bana e Costa, C. A. (2018). Indicators for evaluating European Population Health: A Delphi selection process. BMC Public Health, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G. , & Reichel, A. (2006). Tourist Destination Risk Perception: The Case of Israel. Journal of Hospitality & Leisure Marketing, 14(2), 83–108. [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, G. , & Reichel, A. (2011). An exploratory inquiry into destination risk perceptions and risk reduction strategies of first time vs. repeat visitors to a highly volatile destination. Tourism Management, 32(2), 266–276. [CrossRef]

- Gray, C; The managerial process (7th ed: , & Larson, E. (2018). Project Management.

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of covid-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M. K., Ismail, A. R., & Islam, M. D. F. (2017). Tourist risk perceptions and revisit intention: A critical review of literature. Cogent Business & Management, 4(1), 1412874. [CrossRef]

- Hasson, F. , Keeney, S., & McKenna, H. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi Survey Technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(4), 1008–1015. [CrossRef]

- Huang, I. B., Keisler, J., & Linkov, I. (2011). Multi-criteria decision analysis in Environmental Sciences: Ten Years of applications and Trends. Science of The Total Environment, 409(19), 3578–3594. [CrossRef]

- Jardim, J. Jardim, J., Baltazar, M., Silva, J., & Vaz, M. (2015). Airports operational performance and efficiency evaluation based on multicriteria decision analysis (MCDA) and data envelopment analysis (DEA) Tools. Journal of Spatial and Organizational Performance, 3(4), 296–310.

- Jin, N. (P., Line, N. D., & Merkebu, J. (2015). The impact of Brand Prestige on trust, perceived risk, satisfaction, and loyalty in upscale restaurants. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 25(5), 523–546. [CrossRef]

- Jonas, A. , Mansfeld, Y., Paz, S., & Potasman, I. (2010). Determinants of health risk perception among low-risk-taking tourists traveling to developing countries. Journal of Travel Research, 50(1), 87–99. [CrossRef]

- Karl, M. (2018). Risk and uncertainty in travel decision-making: Tourist and Destination Perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 57(1), 129–146. [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, E. , Bloom, J., & Leibold, M. (1994). Using the Delphi technique to predict future tourism potential. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 12(7), 18–29. [CrossRef]

- Keeney, S. , Hasson, F., & McKenna, H. P. (2001). A critical review of the Delphi technique as a research methodology for nursing. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 38(2), 195–200. [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M. , Crotts, J. C., & Law, R. (2007). The impact of the perception of risk on international travellers. International Journal of Tourism Research, 9(4), 233–242. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. -K., Song, H.-J., Bendle, L. J., Kim, M.-J., & Han, H. (2012). The impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions for 2009 H1N1 influenza on travel intentions: A model of goal-directed behavior. Tourism Management, 33(1), 89–99. [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A. , & Gibson, H. (2003). Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(3), 606–624. [CrossRef]

- Li, J. , Nguyen, T. H., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. A. (2021). Coronavirus impacts on post-pandemic planned travel behaviours. Annals of Tourism Research, 86, 102964. [CrossRef]

- Li, N. , & Murphy, W. H. (2013). Prior consumer satisfaction and alliance encounter satisfaction attributions. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(4), 371–381. [CrossRef]

- Li, S. R., & Ito, N. (2021). "Nothing can stop me!" perceived risk and travel intention amid the Covid-19 pandemic: A Comparative Study of Wuhan and Sapporo. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021, 490–503. [CrossRef]

- Longaray, A. , Ensslin, L., Ensslin, S., Alves, G., Dutra, A., & Munhoz, P. (2018). Using MCDA to evaluate the performance of the logistics process in public hospitals: The case of a Brazilian teaching hospital. International Transactions in Operational Research, 25(1), 133–156. [CrossRef]

- Mao, C. -K., Ding, C. G., & Lee, H.-Y. (2010). Post-SARS tourist arrival recovery patterns: An analysis based on a catastrophe theory. Tourism Management, 31(6), 855–861. [CrossRef]

- Maser, B. , & Weiermair, K. (1998). Travel decision-making: From the vantage point of perceived risk and information preferences. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 7(4), 107–121. [CrossRef]

- Matiza, T. (2020). Post-Covid-19 crisis travel behaviour: Towards mitigating the effects of perceived risk. Journal of Tourism Futures. [CrossRef]

- Moonasar, D., Pillay, A., Leonard, E., Naidoo, R., Mngemane, S., Ramkrishna, W., Jamaloodien, K., Lebese, L., Chetty, K., Bamford, L., Tanna, G., Ntuli, N., Mlisana, K., Madikizela, L., Modisenyane, M., Engelbrecht, C., Maja, P., Bongweni, F., Furumele, T., … Pillay, Y. (2021). Covid-19: Lessons and experiences from South Africa’s first surge. BMJ Global Health, 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, L. Moutinho, L. (2000). Strategic management in Tourism. CABI Publishing.

- Novelli, M. , Gussing Burgess, L., Jones, A., & Ritchie, B. W. (2018). 'no ebola…still doomed' – the ebola-induced tourism crisis. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 76–87. [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C. , & Pawlowski, S. D. (2004). The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Information & Management, 42(1), 15–29. [CrossRef]

- Park, I.-J., Kim, J., Kim, S. (S., Lee, J. C., & Giroux, M. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on travelers’ preference for crowded versus non-crowded options. Tourism Management, 87, 104398. [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A. , Jeong, G.-H., Reichel, A., van Boemmel, H., Lusson, J. M., Steynberg, L., State-Costache, O., Volo, S., Kroesbacher, C., Kucerova, J., & Montmany, N. (2004). The relationship between risk-taking, sensation-seeking, and the tourist behavior of Young Adults: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Travel Research, 42(3), 251–260. [CrossRef]

- Quintal, V. A., Lee, J. A., & Soutar, G. N. (2010). Risk, uncertainty and the theory of planned behavior: A tourism example. Tourism Management, 31(6), 797–805. [CrossRef]

- Rebell, B; //www: (2021, February 23). How to manage the new financial risks of Vacation Travel. Tally. Retrieved December 30, 2021, from https.

- Reisinger, Y. , & Mavondo, F. (2005). Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: Implications of Travel Risk Perception. Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 212–225. [CrossRef]

- Ren, M., Park, S., Xu, Y., Huang, X., Zou, L., Wong, M. S., & Koh, S.-Y. (2022). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on travel behavior: A case study of domestic inbound travelers in Jeju, Korea. Tourism Management, 92, 104533. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B. W. (2004). Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 25(6), 669–683. [CrossRef]

- Rittichainuwat, B. N., & Chakraborty, G. (2009). Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. Tourism Management, 30(3), 410–418. [CrossRef]

- Roehl, W. S., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (1992). Risk perceptions and pleasure travel: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 30(4), 17–26. [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G. , & Wright, G. (2011). The Delphi technique: Past, present, and future prospects — introduction to the special issue. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 78(9), 1487–1490. [CrossRef]

- Santana, G. (2004). Crisis Management and tourism. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 15(4), 299–321. [CrossRef]

- Santana, P. , Freitas, Â., Stefanik, I., Costa, C., Oliveira, M., Rodrigues, T. C., Vieira, A., Ferreira, P. L., Borrell, C., Dimitroulopoulou, S., Rican, S., Mitsakou, C., Marí-Dell'Olmo, M., Schweikart, J., Corman, D., & Bana e Costa, C. A. (2020). Advancing tools to promote health equity across European Union regions: The Euro-Healthy Project. Health Research Policy and Systems, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A. , & Pennington-Gray, L. (2014). Perceptions of crime at the Olympic Games. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 20(3), 225–237. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G. , Saayman, M., & Saayman, A. (2012). Identifying risks facing the South African tourism industry. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 15(2), 190–206. [CrossRef]

- Shi, C. , Zhang, Y., Li, C., Li, P., & Zhu, H. (2020). using the Delphi method to identify risk factors contributing to adverse events in residential aged care facilities. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, Volume 13, 523–537. [CrossRef]

- Shin, H., Nicolau, J. L., Kang, J., Sharma, A., & Lee, H. (2022). Travel decision determinants during and after COVID-19: The role of Tourist Trust, travel constraints, and attitudinal factors. Tourism Management, 88, 104428. [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID- 19.

- Simpson, P. M., & Siguaw, J. A. (2008). Perceived travel risks: The Traveller Perspective and manageability. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(4), 315–327. [CrossRef]

- Staff, L; //digitalrepository: A. D. B. (2009). Negative impact on Mexican Tourism Continues from April Outbreak of Swine Flu. https://doi.org/https.

- Sönmez, S. F., & Graefe, A. R. (1998). Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. Journal of Travel Research, 37(2), 171–177. [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, S. -H., Tzeng, G.-H., & Wang, K.-C. (1997). Evaluating tourist risks from Fuzzy Perspectives. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(4), 796–812. [CrossRef]

- UNWTO; //www: (2021). World Tourism Organization. UNWTO. Retrieved October 30, 2021, from https.

- Van Schoubroeck, S. , Springael, J., Van Dael, M., Malina, R., & Van Passel, S. (2019). Sustainability Indicators for biobased chemicals: A Delphi study using multicriteria decision analysis. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 144, 198–208. [CrossRef]

- Venhorst, K. , Zelle, S. G., Tromp, N., & Lauer, J. A. (2014). Multi-criteria decision analysis of breast cancer control in low- and middle- income countries: Development of a rating tool for policymakers. Cost-Effectiveness and Resource Allocation, 12(1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Vidal, L. -A., Marle, F., & Bocquet, J.-C. (2011). Using a Delphi process and the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to evaluate the complexity of projects. Expert Systems with Applications, 38(5), 5388–5405. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A. C. L., Oliveira, M. D., & Bana e Costa, C. A. (2020). Enhancing knowledge construction processes within multicriteria decision analysis: The Collaborative Value Modelling Framework. Omega, 94, 102047. [CrossRef]

- von Bergner, N. M., & Lohmann, M. (2014). Future challenges for Global Tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 53(4), 420–432. [CrossRef]

- Wen, J. , Kozak, M., Yang, S., & Liu, F. (2020). Covid- 19. [CrossRef]

- WHO; //Covid19: (2021). Who coronavirus (Covid-19) dashboard. World Health Organization. Retrieved November 30, 2021, from https.

- Williams, A. M., & Baláž, V. (2013). Tourism, risk tolerance and competences: Travel Organization and tourism hazards. Tourism Management, 35, 209–221. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y; Launching the Annals of Tourism Research's Curated Collection on coronavirus and tourism: , Zhang, & Rickly, J. (2021). A review of early COVID-19 research in tourism.

- Zenker, S., Braun, E., & Gyimóthy, S. (2021). Too afraid to travel? development of a pandemic (COVID-19) Anxiety Travel Scale (PATS). Tourism Management, 84, 104286. [CrossRef]

- Çetinsöz, B. C., & Ege, Z. (2013). Impacts of perceived risks on tourists' revisit intentions. Anatolia, 24(2), 173–187. [CrossRef]

| 1 | Covid-19 is a respiratory disease caused by a coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), discovered in the late 2019 in China. |

| 2 | i.e., >50% “strongly agree” responses while at the same time <33.3% of “strongly disagree” and “disagree” being approved by the “absolute majority.” |

| Authors | Article Title | Risk Categories | Risk dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roehl & Fesenmaier (1992) | Risk Perceptions and Pleasure Travel: An exploratory analysis | Physical-equipment risk Vacation risk Destination risk |

Destination-related Vacation-related Time risk; Satisfaction risk; Financial risk; Psychological risk |

| Tsaur et al. (1997) | Evaluating tourist risks from fuzzy perspectives | Transportation Law and order Hygiene Accommodation Weather Sightseeing spot Medical support |

Safety of transportation; convenience of telecommunication facilities; safety of driving Political instability; possibility of criminal attack; attitude of locals Infectious disease; hygiene of catering conditions Hotel fire control system; hotel security system Difference of weather change; possibility of natural disasters Safety of recreational facilities; quality of management staff Degree of assistance available in case of an accident; completeness of medical service system |

| Simpson & Sigauw (2008) | Perceived travel risks: The traveler perspective and manageability | Physical risk Performance risk Psychological risk Financial risk Social risk |

Health and well-being; Criminal harm Transportation performance; Travel service performance; Travel & destination environment Generalized fears Monetary concerns; Property crime Concern for others; Concern about others |

| Dolnicar (2005) | Understanding barriers to leisure travel: Tourist fears as a marketing basis | Political risk Health risk Environment risk Plan risk Property risk |

Terrorist attacks; Unstable political environment Healthcare access; Life-threatening diseases Natural disasters; Landslides Unreliable airlines; Inexperienced operations Theft; luggage loss |

| Jonas et al. (2010) | Determinants of health risk perception among low-risk-taking tourists traveling to developing countries | Environmentally-induced risk factors Semi-controlled risk factors Fully controlled risk factors |

Water quality, healthcare, food safety, disease, infection Physical injuries, safety, environmental-physical conditions Sexual and drug abuse health risks |

| Boksberger et al. (2007) | Multidimensional analysis of perceived risk in commercial air travel | Financial risk Functional risk Personal risk Social risk Time risk |

Services providing value-for-money Quality of service Hurt passenger in-flight Reputation damage Checking-in, schedule delays, wasting time |

| Fuchs & Reichel (2011) | An exploratory inquiry into destination risk perceptions and risk reduction strategies of first time vs. repeat visitors to a highly volatile destination | Artificial risk Financial risk Service Quality risk Psychosocial risk Natural disaster & Accident risk Food safety issues & Weather |

Crime; terrorist attacks; political unrest Personal economic consequences Strikes; unsatisfactory facilities; unfriendly shopkeepers Trip impact on self-image; impression of others Possibility of occurrence Food security; possibility of adverse weather |

| Cetinsoz & Ege (2013) | Impacts of perceived risks on tourists' revisit intentions | Physical risk Satisfaction risk Socio-psychological risk Time risk Performance risk |

Natural disaster; experience violent riots; traffic accidents; loss of baggage; robbery; infectious disease; unfavorable weather conditions; sexual harassment; cultural conflicts; negative attitudes of locals Urban pollution; unsafe nightlife; poor hygiene and environmental conditions; uncomforting food safety; overvalued currency; unexpected expenses Worrying about security during vacation; insufficient urban transportation; unfulfilled expectations Wasting vacation time; wasting time in general; feeling disappointed after vacation Language problems; experiencing faults in tour organization |

| Chew & Jahari (2014) | Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan | Financial risk Physical risk Socio-psychological risk |

Facilities will not be a good value for money; worry that the trip will be financially burdening Natural disasters; food safety Change impression from friends |

| Reisinger & Mavondo (2005) | Travel anxiety and intentions to travel internationally: Implications of Travel Risk Perception | Terrorism risk Health and Financial risk Socio-cultural risk |

Terrorist attacks Health; physical; financial; functional Time; satisfaction; psychological; social |

| An et al. (2010) | Risk factors at the travel destination: Their impact on air travel satisfaction and repurchase intention | Natural disaster risk Physical risk Political risk Performance risk |

Probability of occurring natural disasters Possibility of being physically harmed from disease, accident, terrorism, etc. Perceived degree of instability of the destination political environment Perceived degree of the difference between travel cost and value of opportunity cost |

| Rittichainuwat & Chakraborty (2009) | Perceived travel risks regarding terrorism and disease: The case of Thailand. | Terrorism Increase in travel cost Lack of novelty Disease Travel inconvenience Deterioration of tourist attractions |

Bali bomb; War in Iraq; Sept 11, 2001; Political turmoil in southern Thailand Increase of hotel room rate; increase of tour package; increase of air fare lack of: new travel experience; new attractions, and boredom of traveling to the same place SARS, Birdflu, Anthrax Polluted and crowded travel attractions; hostile locals; cheating when shopping; dissatisfaction with the previous trip Language barriers, long travel time, traffic jams |

| Sonmez & Graefe (1998) | Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety | Equipment/functional risk Financial risk Health risk Physical risk Political instability risk Psychological risk Satisfaction risk Social risk Terrorism risk Time risk |

Possibility of mechanical, equipment, organizational problems occurring during travel or at the destination (transportation, accommodations, attractions) Not providing value for money spent Becoming sick while traveling or at the destination Physical danger or injury detrimental to health Becoming involved in the political turmoil of the country visited Disappointment with travel experience Dissatisfaction with travel experience Disapproval of vacation choices or activities by friends/family/associates Being involved in a terrorist attack Travel experience taking too much time or will waste time |

| Casidy & Wymer (2016) | A risk worth taking: Perceived risk as moderator of satisfaction, loyalty, and willingness-to-pay premium price | Financial risk Performance risk Social risk Psychological risk |

Lose money due to canceling trip; long-term costs; loss of convenience from wasting time booking and effort booking Hot hotel brands perform; chance of something being wrong with the service; not delivering as promised Friends not thinking well of the individual; causing one to look foolish by people whose opinions they value Tension, unwanted anxiety, worry |

| Authors | Article title | Risk categories | Risk dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zhan et al. (2020) | A risk perception scale for travel to a crisis epicentre: Visiting Wuhan after covid-19. | Financial risk Health risk Social risk Psychological risk |

Afraid costs are higher than before; unexpected expenses; not getting good value for money Accommodation facilities not sanitary; diet unhealthy; worried about getting sick during travel; receiving timely treatment for illness or other physical harm People who care about me will be anxious; people who care about me think I'm irrational; afraid it will cause conflicts between couples/family members Tourist facilities will not be good enough; tourist service will not be good enough |

| Lee et al. (2021) | A study on tourists’ perceived risks from covid-19 using Q-methodology. | Worrying about health Worrying about potential problems Worrying about tourism itself Worrying about issues |

Own risk awareness of COVID-19 infection high Concerned about infection; discrimination at the destination; poor-quality medical systems Concerned by unexpected situations at tourism destinations and poor quality of tourism services More concerned about the situation in Korea than infection |

| Matiza (2020) | Post-covid-19 crisis travel behaviour: Towards mitigating the effects of perceived risk. | Health risk Social risk Psychological risk |

Potential hazards to the health and well-being of the tourist; perceived susceptibility and severity How the choice to undertake travel and tourism would affect the tourists’ social reference groups Possibility that travel and tourism experience will not reflect favorably on the tourist concerning the image of self and personality |

| Li et al. (2021) | Seeing the invisible hand: Underlying effects of covid-19 on tourists’ behavioural patterns | Performance risk Health risk Social risk Psychological risk Image risk Time risk |

Not receiving anticipated vacation-related benefits due to the touristic product or service not performing well People meeting strangers may perceive a higher possibility of COVID-19 infection; further destinations may also increase this perceived risk Possibility that one's friends/family express a negative attitude towards tourism activities during the pandemic; feeling alienated upon returning home Pandemic-related anxiety The media affecting risk perceptions by compromising the destination image and tourism market of certain regions Some services not available at the scheduled time due to travel policies during the pandemic; quarantine-related measures |

| Variables | n | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Gender Female Male Other |

14 5 1 |

70 25 5 |

|

Age (years) 18-24 25-30 31-45 46-60 60+ |

1 5 3 9 2 |

5 25 15 45 10 |

|

Educational Attainment No school Matric Diploma/Bachelor’s Degree Post-graduate PhD |

0 3 13 4 0 |

0 15 65 20 0 |

|

Travel Frequency Once every few years Once a year Twice a year More than twice a year |

11 7 1 1 |

55 35 5 5 |

|

Typical Accommodation Hotel Backpackers/Hostel AirBnB, BnB, Rented Stay with friends/family |

5 3 7 5 |

25 15 35 25 |

|

Continent most travelled Africa Europe North America South America Asia Australia Antarctica |

4 15 0 0 1 0 0 |

20 75 0 0 5 0 0 |

|

Reasons for most travel Business Leisure |

3 17 |

15 85 |

| Round | Questionnaires issued | Questionnaires retrieved | Return Ratio (%) | Number of effective questionnaires | Effective return ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 32 | 20 | 62.5 | 20 | 62.5 |

| Second | 20 | 17 | 85 | 17 | 85 |

| Third | 17 | 16 | 94.1 | 16 | 94.1 |

| Fourth | 16 | 14 | 87.5 | 14 | 87.5 |

| Risk Statement | Mean | Standard Deviation | Very Unlikely (%) | Unlikely (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| There will be additional costs involved in meeting Covid-19 regulations (e.g., PCR tests) (fin) | 4.24 | 0.970 | 0 | 0 |

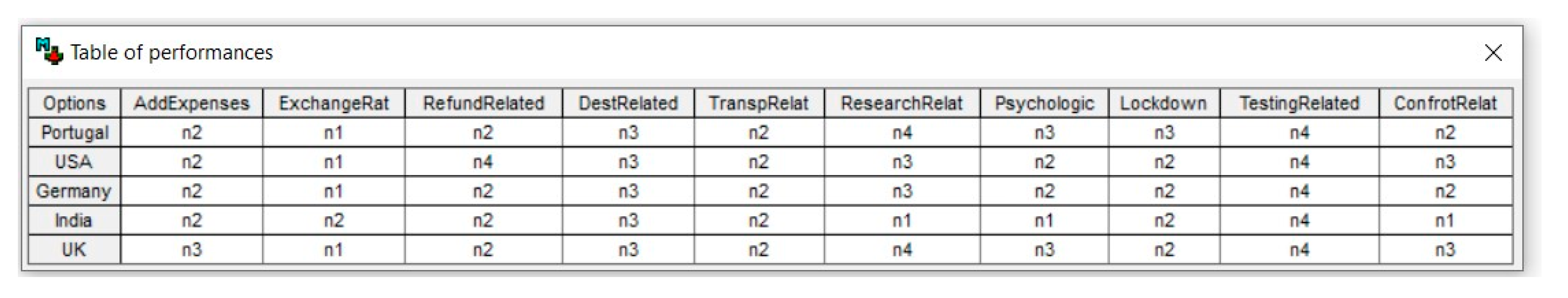

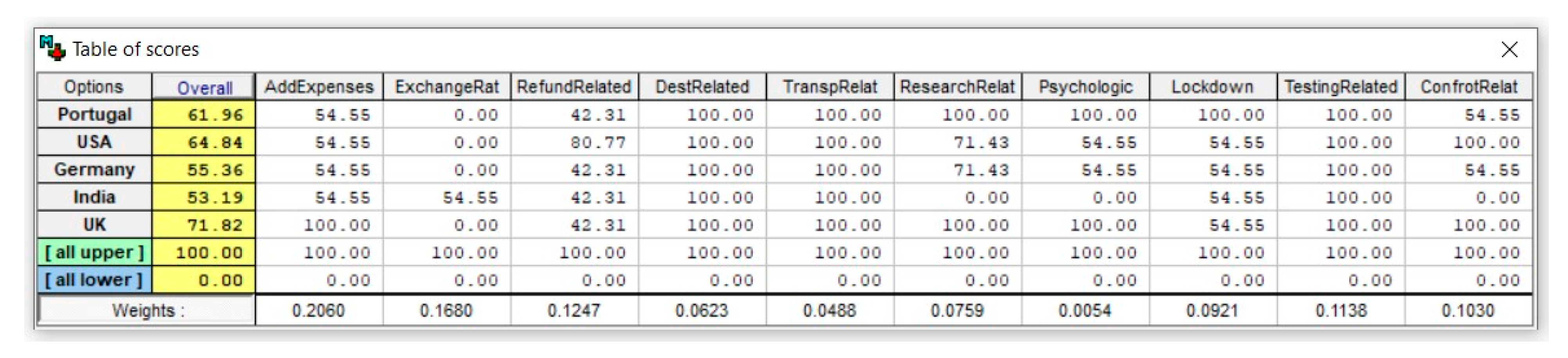

| Criteria | Weighting | Normalized Weights |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Additional expenses | 83 | 20.60 |

| 1.2 Exchange rates | 83 | 16.80 |

| 1.3 Refunds-related | 80 | 12.47 |

| 4.2 Testing-related | 77 | 11.35 |

| 4.3 Comfort-related | 78 | 10.30 |

| 4.1 Lockdowns | 75 | 9.21 |

| 3.1 Researching-related | 71 | 7.59 |

| 2.1 Destination performance | 66 | 6.23 |

| 2.2 Transportation performance | 75 | 4.88 |

| 3.2 Psychological | 68 | 0.54 |

| Impact Levels | Description |

|---|---|

| N5 | In the case of cancellation, full refund obtained with low input of effort to obtain the refund |

| N4 | In the case of cancellation, full refund obtained with high input of effort to obtain the refund |

| N3 | In the case of cancellation, partial refund obtained with low input of effort to obtain the refund |

| N2 | In the case of cancellation, partial refund obtained with high input of effort to obtain the refund |

| N1 | In the case of cancellation, no refund obtained with high input of effort to obtain the refund |

| Risk Category | Risk Dimensions/Criteria | Normalized weights |

|---|---|---|

| Financial | 1.1 Additional expenses 1.2 Exchange rates 1.3 Refunds-related |

20.60 16.80 12.47 |

| Performance | 2.1 Destination 2.2 Transportation |

6.23 4.88 |

| Planning | 3.1 Researching-related 3.2 Psychological |

7.59 0.54 |

| Regulations | 4.1 Lockdowns 4.2 Testing-related 4.3 Comfort-related |

9.21 11.38 10.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).