Submitted:

03 May 2023

Posted:

04 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

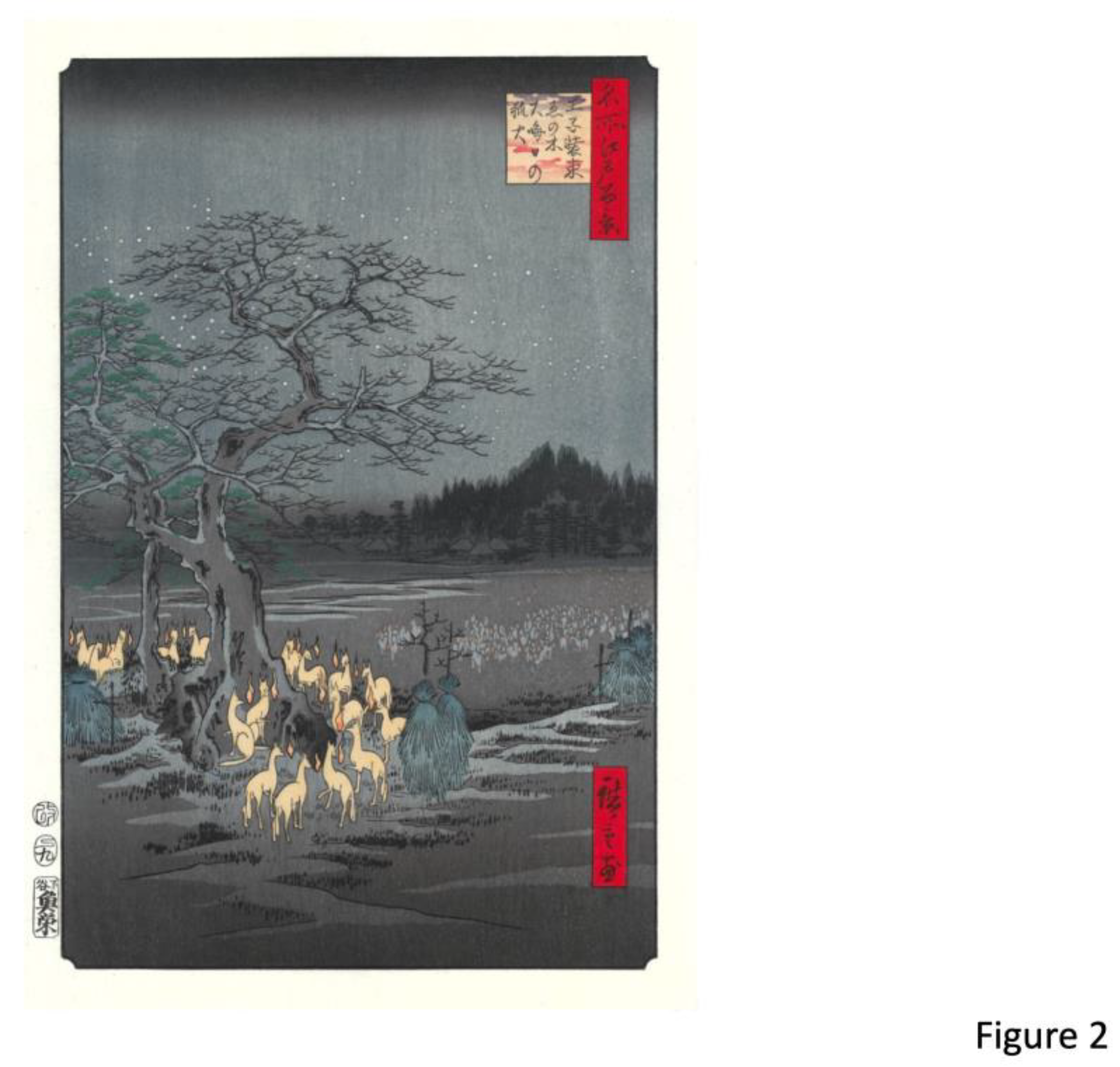

2. Folklores

3. The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter

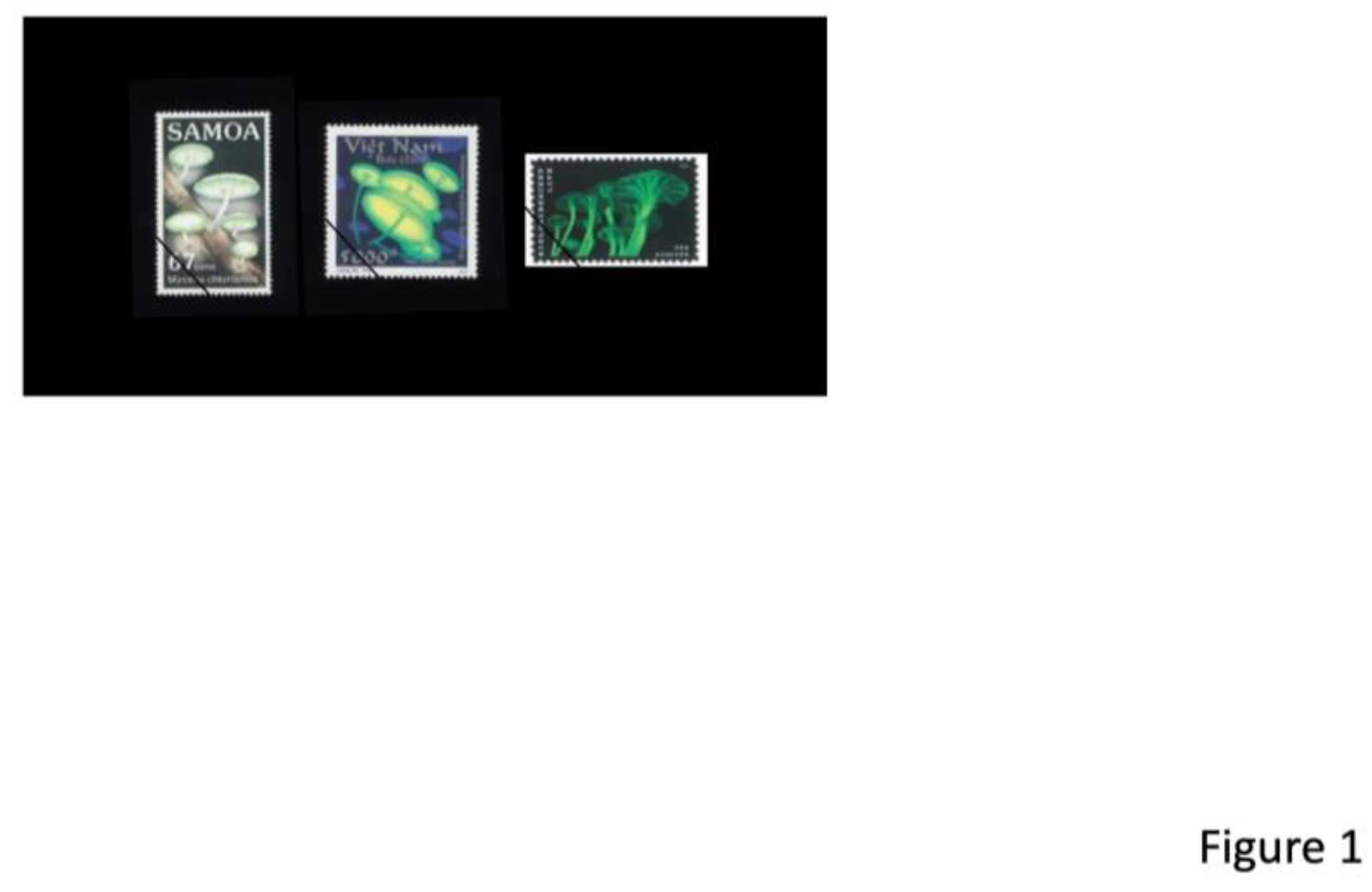

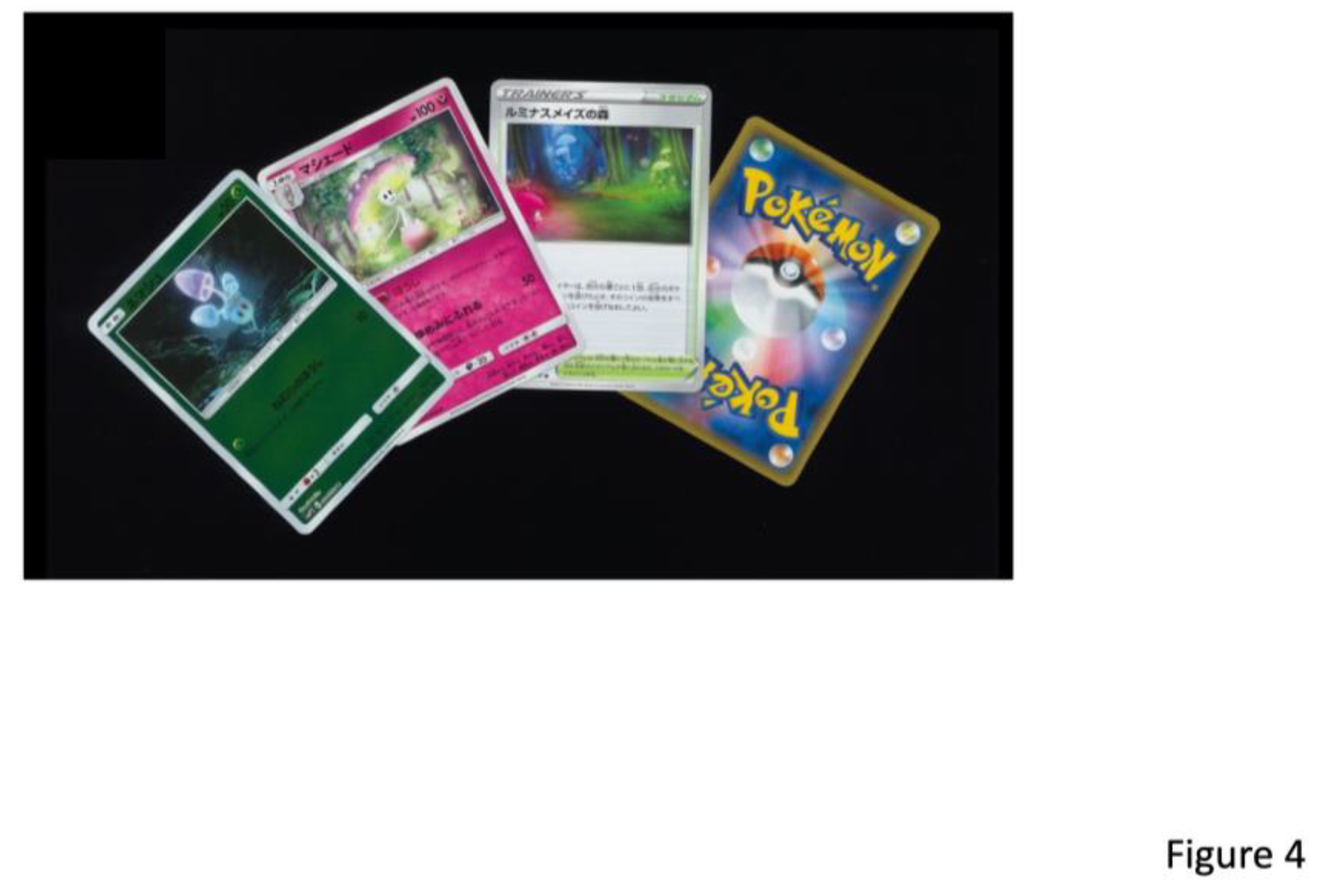

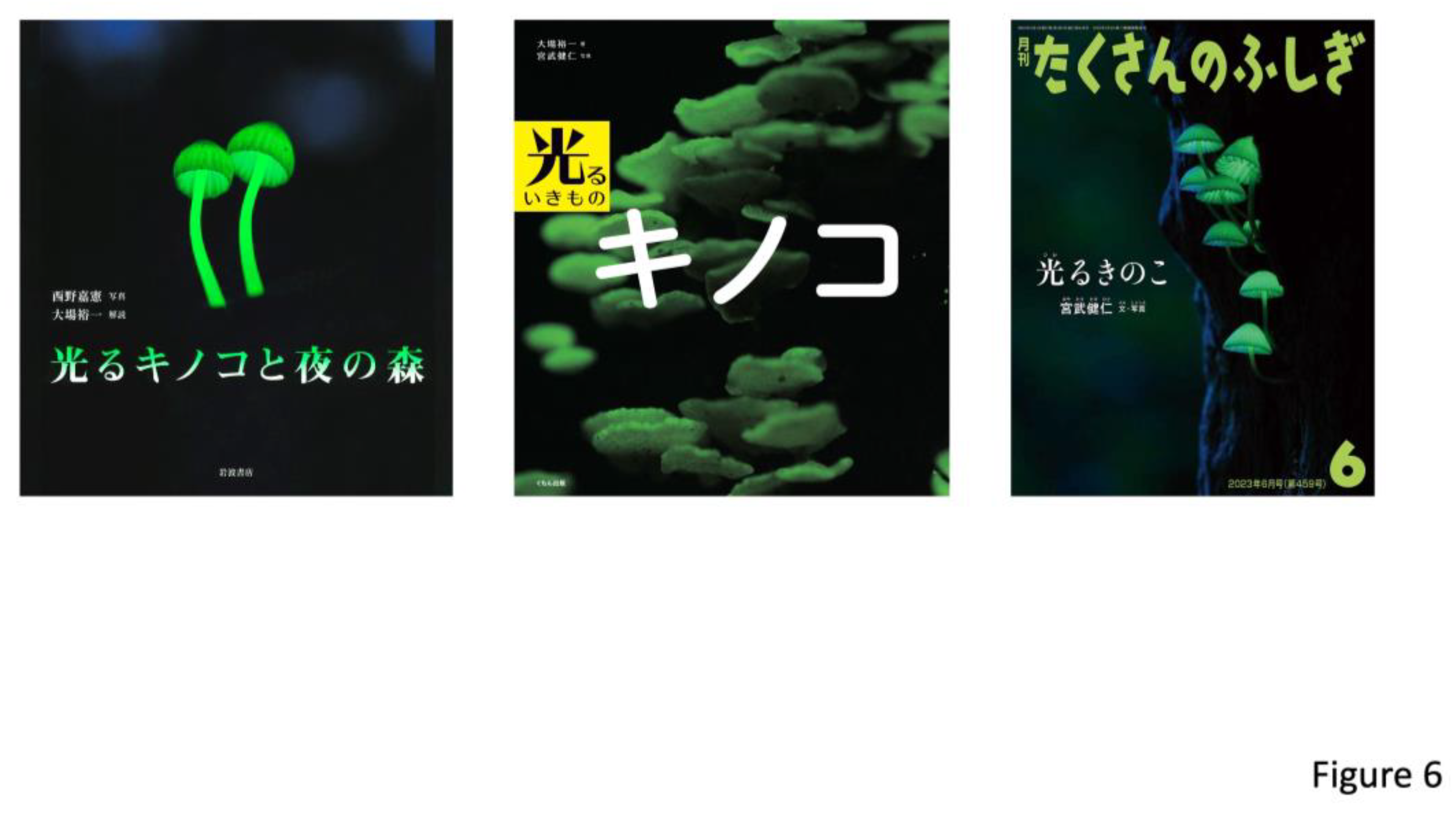

4. Current commercialization

5. Taxonomy

5.1. Bioluminescent species in Japan

5.2. Nonbioluminescent species based on samples collected from Japan

5.3. Potentially bioluminescent species in Japan

6. Bioluminescence

7. Biological function

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Informed-Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hosoya, T. History and the current status of fungal inventory and databasing in Japan. In Proceedings of the 7th and 8th Symposia on Collection Building and Natural History Studies in Asia and the Pacific Rim; Tomida, Y. et al., et al., Eds.; National Science Museum Monographs: Ibaraki, Japan, 2006; pp. 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Sugahara, T. Japanese and mushrooms. J. Cookery Sci. Jpn. 2001, 34, 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Guy, N. Kinoko: A window into the mystical world of Japanese mushrooms; Amazon on demand; 2023; ISBN 979-8987537671. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, J. Primer of Yamigaku (Study of dark); Shueisha: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, K. Introduction to Yokai Culture: Monsters, Ghosts, and Outsiders in Japanese History; Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, H. Occurrence of the luminous oligochæte Microscolex phosphoreus (Dug.). Annot. Zool. Japon 1935, 15, 200–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, S. On the luminous earthworm Hikari-umi-mimizu. Rigakukai 1938, 36, 1–7. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara, K.; Higa, Y. New record of the luminous millipede from Okinawa. Edaphologia 1997, 59, 61–62, (in Japanese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwabara, S. An origin of firefly luminescence?: Luminescence of Collembola. SCIaS 1997, 2, 10. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Kurogi, S. Mushrooms in Miyazaki Prefecture (Miyazaki no Kinoko); Komyakusha: Miyazaki, Japan, 2015. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Iwama, A. An unexpected finding of the luminescent Cruentomycena. Mycologist Circle of Japan 2020, 2–3. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, E.N. A History of Luminescence. From the Earliest Times Until 1900; Am. Phil. Soc.: Philadelphia, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Watasé, S. On the Fireflies (Hotaru no Hanashi); Kaiseikan: Tokyo, Japan, 1902. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, S. Shiranui, Hitodama, and Kitsune-bi; Shunyodo: Tokyo, Japan, 1931. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Togawa, A. Haguro-san Yobanashi (or Haguro-san Yawa). Tabi to Densetsu 1944, 193, 13–24. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, T. Nankou Chawa. In Nihon Zuihitsu Taisei; Yoshikawakobunkan: Tokyo, Japan, 1977; pp. 413–448. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, T. Yamagata-ken ni okeru Torimono no Keifu. Seikou Minzoku 1991, 135, 36–37. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi, M. On the luminescence of mushrooms. Kinoko-ken Dayori 2006, 28, 10–20. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, E.; Ota, Y.; Hattori, T.; Sahashi, N.; Kikuchi, T. Ecology of Armillaria species on conifers in Japan. For. Path. 2011, 41, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, I. The Smoke of a Pipe, Still; Asahi Shimbun Co.: Tokyo, Japan, 1972. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, A. Kinoko Zukan; Natsume Pub.: Tokyo, Japan, 2017. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nishino, Y.; Oba, Y. Luminous Mushrooms with Night Forests; Iwanami Shoten Pub.: Tokyo, Japan, 2013. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Oba, Y. Luminous Organisms of the World: Diversity, Ecology, and Biochemistry; The University of Nagoya Press: Nagoya, Japan, 2022. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, E.N. Bioluminescence; Academic Press: New York, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Keene, D. The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter; Kodansha International: Tokyo, Japan, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hotate, M. Shining Princess and the Sovereign myth (Kaguya-himé to Ouken-shinwa); Yosensha: Tokyo, Japan, 2010. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, K.; Suzuki, H. The origins of fiction. Kokubungaku 1993, 38, 6–24. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda, A. Miscellaneous notes on fungi. Bot. Mag. Tokyo 1920, 34, 194–196. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Shidei, T. Report of fungal flora in bamboo forest. Trans. Mycol. Soc. Japan 1974, 15, 251–257. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Haneda, Y. Luminous Organisms; Kouseisha-Kouseikaku: Tokyo, Japan, 1985. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Imazeki, R.; Otani, Y.; Hongo, T. Mushrooms in Japan; Yama-Kei Pub.: Tokyo, Japan, 1988. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kyoto Prefecture. The List of Biological and Geological Components of the Natural Environment 2015, Red Data Book of Kyoto Prefecture 2015, Supplementary; Kyoto Prefecture: Kyoto, Japan, 2015. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, S. Fireflies; Nippon Hakkō Seibutsu Kenkyu Kai: Tokyo, Japan, 1935. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ohba, N. Mystery of Fireflies; Yokosuka City Mus: Yokosuka, Japan, 2004. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Oba, Y.; Miyatake, T. Luminous Creatures, Mushrooms; Kumon Pub: Tokyo. Japan, 2015. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Miyatake, T. Luminous mushrooms (World of Wonders); Fukuinkan Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 2023. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Niitsu, H.; Hanyuda, N.; Sugiyama, Y. Cultural properties of a luminous mushroom, Mycena chlorophos. Mycoscience 2000, 41, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niitsu, H.; Hanyuda, N. Fruit-body production of a luminous mushroom, Mycena chlorophos. Mycoscience 2000, 41, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ise Shimbun. Enjoy luminous mushroom. Iwade Research Institute of Mycology Group in Tsu City sells the culture kit. (2021, May 24). The Ise Shimbun Chusei Local, Japan. (in Japanese). 24 May.

- Neda, H. Kinoko Museum; Yasaka Shobo: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, S. Studies on the luminous fungus, Pleurotus japonicus sp. nov. J. Coll. Sci. Tokyo Imp. Univ. 1915, 35, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayasi, Y. Seven luminous mycomycetes from Bonin Islands. Bull. Biogeographic. Soc. Jpn. 1937, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Corner, E.J.H. Further description of luminous agarics. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1954, 37, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, E.J.H. The Marquis: A Tale of Syonan-to; Heinemann Asia: Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wassink, E.C. On fungus luminescence; Mededelingen Landbouwhogeschool, Wageningen, H. Veenman & Zonen: Wageningen, Nederland, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Desjardin, D.E.; Oliveira, A.G.; Stevani, C.V. Fungi bioluminescence revisited. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2008, 7, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terashima, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Taneyama, Y. The Fungal Flora in Southwestern Japan: Agarics and Boletes; Tokai Univ. Press: Kanagawa, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Pérez, A.; Desjardin, D.E.; Perry, B.A.; Ramírez-Cruz, V.; Ramírez-Guillén, F.; Villalobos-Arámbula, A.R.; Rockefeller, A. New species and records of bioluminescent Mycena from Mexico. Mycologia 2019, 111, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lin, W.-W.; Kao, H.-W. Mycena jingyinga, Mycena luguensis, and Mycena venus: three new species of bioluminescent fungi from Taiwan. Taiwania 2020, 65, 396–406. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, N. On the report about Japanese poisonous mushrooms part 1 by Kichindo Inoko. J. Plant Res 1889, 3, 47–51. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Haneda, Y. Luminous Organisms of Japan and the Far East. In The Luminescence of Biological Systems; Johnson, F.H., Ed): Am. Assoc. Adv. Sci.: Washington DC, USA, 1955; pp. 335–385. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, A.L.C.; Tan, Y.-S.; Desjardin, D.E.; Musa, Md.Y.; Sabaratnam, V. Taxonomic and phylogenetic re-evaluation of Mycena illuminans. Mycologia 2013, 105, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katumoto, K. List of Fungi Recorded in Japan; The Kanto Branch of the Mycological Society of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2010. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, H. An impact on the finding of the luminescent Cruentomycena by Ami Iwama. Mycologist Circle of Japan 2020, 4. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Taneyama, Y. Cruentomycena was bioluminescent! Mycologist Circle of Japan 2020, 5. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Okuzawa, Y.; Okuzawa, M. Mushroom Etymology and Dialect Dictionary; Yama-Kei Pub.: Tokyo, Japan, 1998. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kobayasi, Y. Contributions to the luminous fungi from Japan. J. Hattori Bot. Lab. 1951, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- GBIF.org. GBIF Home Page. 2023. Available from: https://www.gbif.org (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Kawai, D. Handbook of Mushrooms in Oirase Stream (Oirase Keiryu, Kinoko Handbook), spring – early summer; NPO Oiken: Aomori, Japan, 2022. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Imazeki, R.; Hongo, T. Colored Illustrations of Mushrooms of Japan, Vol. I; Hoikusha: Osaka, Japan, 1987. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Search System of Japanese Red Data; Association of Wildlife Research and EnVision (accessed on 15 Apr 2023), http://jpnrdb.com/index.html.

- Tanaka, Y.; Kasuga, Y.; Oba, Y.; Hase, S.; Sakakibara, Y. Genome sequence of the luminous mushroom Mycena chlorophos for searching fungal bioluminescence genes. Luminescence 2014, 29, 47–48. [Google Scholar]

- Miyagi, G. Notes on luminous fungi, Filoboletus manipularis, on Okinawa. Bull. Coll. Sci. Univ. Ryukyus 1960, 4, 77–87. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Hioki, K. (Ed.) Sanshu Kidan; Ishikawa Prefecture Library Association: Ishikawa, Japan, 1933. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, S. Studies on a luminous fungus, Pleurotus japonicus sp. nov. Bot Mag Tokyo 1910, 24, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, S. Macrofungi of Aomori; Access 21 Pub.: Aomori, Japan, 2017. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra, Y.K. (translation) The Konjaku Tales. Japanese section (Honcho-Hen)(III) from a Medieval Japanese Collection; Kansai Gaidai Univ. Pub.: Osaka, Japan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Watari, T.; Tachibana, T.; Okada, A.; Nishikawa, K.; Otsuki, K.; Nagai, N.; Abe, H.; Nakano, Y.; Takagi, S.; Amano, Y. A review of food poisoning caused by local food in Japan. J. Gen. Fam. Med. 2021, 22, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, K.; Ohashi, M.; Tada, M.; Yamada, Y. Illudin S (lampterol). Tetrahedron 1965, 21, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Shirahama, H.; Ichihara, A.; Fukuoka, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Mori, Y.; Watanabe, M. Structure of lampterol (illudin S). Tetrahedron 1965, 21, 2671–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, M.-J.; Shim, D.; Ryoo, R. De novo genome assembly of the bioluminescent mushroom Omphalotus guepiniiformis reveals an Omphalotus-species lineage of the luciferase. Genomics 2022, 114, 110514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukasawa, Y.; Osono, T.; Takeda, H. Beech log decomposition by wood-inhabiting fungi in a cool temperate forest floor: a quantitative analysis focused on the decay activity of a dominant basidiomycete Omphalotus guepiniformis. Ecol. Res. 2010, 25, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooka, M. Easy-Access Index of Haiku Seasonal Words (Autumn); Yushikan: Tokyo, Japan, 2005. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Wassink, E.C. Luminescence in Fungi. In Bioluminescence in Action; Herring, P.J., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, USA, 1978; pp. 171–197. [Google Scholar]

- Kudo, S.; Tezuka, Y.; Yonaiyama, H. Fungi of Aomori; Graph Aomori: Aomori, Japan, 1998. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi, M. Light emission of Armillaria tabescens (Scop.:Fr.) Emel –Measurement of light emission of mushrooms using chemiluminescence detector–. Bull. Koriyama Women’s Univ. 2013, 49, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, R.A.; Wilson, A.W.; Séne, O.; Henkel, T.W.; Aime, M.C. Resolved phylogeny and biogeography of the root pathogen Armillaria and its gasteroid relative, Gyanogaster. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncalvo, J.-M.; Lutzoni, F.M.; Rehner, S.A.; Johnson, J.; Vilgalys, R. Phylogenetic relationships of agaric fungi based on nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Syst. Biol. 2000, 49, 278–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macrae, R. Interfertility studies and inheritance of luminosity in Panus stypticus. Can. J. Res. 1942, 20c, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlobay, A.A.; Sarkisyan, K.S.; Mokrushina, Y.A.; Marcet-Houben, M.; Serebrovskaya, E.O.; Markina, N.M.; Somermeyer, L.G.; Gorokhovatsky, A.Y.; Vvedensky, A.; Purtov, K.V.; Petushkov, V.N.; Rodionova, N.S.; Chepurnyh, T.V.; Fakhranurova, L.I.; Guglya, E.B.; Ziganshin, R.; Tsarkova, A.S.; Kaskova, Z.M.; Shender, V.; Abakumov, M.; Abakumova, T.O.; Povolotskaya, I.S.; Eroshkin, F.M.; Zaraisky, A.G.; Mishin, A.S.; Dolgov, S.V.; Mitiouchkina, T.Y.; Kopantzev, E.P.; Waldenmaier, H.E.; Oliveira, A.G.; Oba, Y.; Barsova, E.; Bogdanova, E.A.; Gabaldón, T.; Stevani, C.V.; Lukyanov, S.; Smirnov, I.V.; Gitelson, J.I.; Kondrashov, F.A.; Yampolsky, I.V. Genetically encodable bioluminescent system from fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 12728–12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, C.; Lucas, J. (Eds.) . The Encyclopedia of Mushrooms; G. P. Putnam’s Sons: New York, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley, M.J.; Curtis, M.A. Characters of new fungi, collected in the North Pacific Exploring Expedition by Charles Wright. Proc. Amer. Acad. Arts Sci. 1860, 4, 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S. Mycological Flora of Japan. Vol. II. Basidiomycetes No. 5. Agaricales, Gasteromycetales; Yokendo: Tokyo, Japan, 1959. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Desjardin, D.E.; Capelari, M.; Stevani, C.V. A new bioluminescent agaric form São Paulo, Brazil. Fung. Div. 2005, 18, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bothe, F. Über das Leuchten verwesender Blätter und seine Erreger. Planta 1931, 14, 752–765. (in Germany). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berliner, M.D. Studies in fungal luminescence. Mycologia 1961, 53, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treu, R.; Agerer, R. Culture characteristics of some Mycena species. Mycotaxon 1990, 38, 279–309. [Google Scholar]

- Bermudes, D.; Petersen, R.H.; Nealson, K.H. Low-level bioluminescence detected in Mycena haematopus basidocarps. Mycologia 1992, 84, 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josserand, M. Sur la luminescence de “Mycena rorida” en Europe occidentale. Bull. Mens. Soc. Linn. Lyon 1953, 22, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neda, H.; Sato, H. New record of Armillaria fuscipes Petch from Japan. In Abstract of Papers Presented at the 53th Annual Meeting of the Mycological Society of Japan; 2009; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Mihail, J.D. Bioluminescence patterns among North American Armillaria species. Fungal Biology 2015, 119, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M. Searching for luminous mushrooms of the marsh fungus Armillaria ectypa. Field Mycol. 2004, 5, 142–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassink, E.C. Observations on the luminescence in fungi, I, including a critical review of the species mentioned as luminescent in literature. Recueil Trav. Bot. Neerl. 1948, 41, 150–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hongo, T. New taxa of the Agaricales published by T. Hongo from 1973 to 1988. Trans. Mycol. Soc. Jpn. 1989, 30, 499–504. [Google Scholar]

- Harder, C.B.; Laæssøe, T.; Frøslev, T.G.; Ekelund, F.; Rosendahl, S.; Kjøller, R. A three-gene phylogeny of the Mycena pura complex reveals 11 phylogenetic species and shows ITS to be unreliable for species identification. Fungal Biol. 2013, 117, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ota, Y.; Kim, M.-S.; Neda, H.; Klopfenstein, N.B.; Hasegawa, E. The phylogenetic position of an Armillaria species from Amami-Oshima, a subtropical island of Japan, based on elongation factor and ITS sequences. Mycoscience 2011, 52, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, R. Observations and tryals about the resemblances and differences between a burning coal and shining wood. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. 1668, 2, 605–612. [Google Scholar]

- Fabre, J. –H. Recherches sur la cause de la phosphorescence de l’agaric de l’olivier. Ann. Sci. Nat. Bot. 1855, 4, 179–197. (in French). [Google Scholar]

- Goto, Y. Luminous organisms appeared in Edo-period literatures. Bull. Firefly Mus. Toyota Town 2022, 14, 81–86. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, S. Studies on a Luminous fungus, Pleurotus japonicus sp. nov. (Continued from p. 213). Bot. Mag. Tokyo 1910, 24, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airth, R.L.; McElroy, W.D. Light emission from extracts of luminous fungi. J. Bacteriol. 1959, 77, 249–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airth, R.L.; Foerster, G.E.; Behrens, P.Q. The luminous fungi. In Bioluminescence in Progress; Johnson, F.H., Haneda, Y., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, USA, 1966; pp. 203–223. [Google Scholar]

- Airth, R.L.; Foerster, G.E.; Hinde, R. Bioluminescence. In Photobiology of Microorganisms; Halldal, P., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 1970; pp. 417–446. [Google Scholar]

- Airth, R.L.; Foerster, G.E. The isolation of catalytic components required for cell-free fungal bioluminescence. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1962, 97, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airth, R.L.; Foerster, G.E. Enzymes associated with bioluminescence in Panus stypticus luminescence and Panus stypticus non-luminescence. J. Bacteriol. 1964, 88, 1372–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oba, Y. Bioluminescent mechanism of luminous mushroom. Kinoko-ken Dayori 2017, 40, 18–25. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Purtov, K.V.; Petushkov, V.N.; Baranov, M.S.; Mineev, K.S.; Rodionova, N.S.; Kaskova, Z.M.; Tsarkova, A.S.; Petunin, A.I.; Bondar, V.S.; Rodicheva, E.K.; Medvedeva, S.E.; Oba, Y.; Oba, Y.; Arseniev, A.S.; Lukyanov, S.; Gitelson, J.I.; Yampolsky, I.V. The chemical basis of fungal bioluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 8124–8128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwabara, S.; Wassink, E.C. Purification and properties of the active substance of fungal luminescence. In Bioluminescence in Progress; Johnson, F.H., Haneda, Y., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, USA, 1966; pp. 233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Oba, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Martins, G.N.R.; Carvalho, R.P.; Pereira, T.A.; Waldenmaier, H.E.; Kanie, S.; Naito, M.; Oliveira, A.G.; Dörr, F.A.; Pinto, E.; Yampolsky, I.V.; Stevani, C.V. Identification of hispidin as a bioluminescent active compound and its recycling biosynthesis in the luminous fungal fruiting body. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwabara, S.; Cormier, M.J.; Dure, L.S.; Kreiss, P.; Pfuderer, P. Crystalline bacterial luciferase from Photobacterium fischeri. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1965, 53, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, M.; Kajiwara, M.; Nakanishi, K. Fluorescent constituents and cultivation of Lampteromyces japonicus. Chem. Commun. 1970, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, M.; Uyakul, D.; Goto, T. Lampteromyces bioluminescence-2. Lampteroflavin, a light emitter in the luminous mushroom, L. japonicus. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 1169–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyakul, D.; Isobe, M.; Goto, T. Lampteromyces bioluminescence 3. Structure of lampteroflavin, the light emitter in the luminous mushroom, L. japonicus. Bioorg. Chem. 1989, 17, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Jewsbury, R.A. Chemiluminescence of flavins in the presence of Fe(II). J. Photochem. Photobiol. 1995, A91, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, M. New bioluminescent systems in fungi, plant and animals. Nippon Nōgeikagaku Kaishi 1992, 66, 736–741. (in Japanese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kane, D.J.; Fuhrer, B.; Lingle, W.L. Spectral studies on fungal bioluminescence. In Bioluminescence and Chemiluminescence: Fundamentals and Applied Aspects; Campbell, A.K., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1994; pp. 552–555. [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura, O. Learning from Jellyfish (Kurage ni Manabu); Nagasaki Bunken Sha: Nagasaki, Japan, 2010. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura, O. Bioluminescence: Chemical Principles and Methods; World Scientific: Toh Tuck Link, Singapore, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura, O.; Shimomura, S.; Bringer, J.H. Luminous Pursuit: Jellyfish, GFP, and the Unforeseen Path to the Nobel Prize; World Scientific: Toh Tuck Link, Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, H.; Kishi, Y.; Shimomura, O. Panal: a possible precursor of fungal luciferin. Tetrahedron 1988, 44, 1597–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, O. Superoxide-triggered chemiluminescence of the extract of luminous mushroom Panellus stipticus after treatment with methylamine. J. Exp. Bot. 1991, 42, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, O. Structure and non-enzymatic light emission of two luciferin precursors isolated from the luminous mushroom Panellus stipticus. J. Biolumin. Chemilumin. 1993, 8, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, O. The role of superoxide dismutase in regulating the light emission of luminescent fungi. J. Exp. Bot. 1992, 43, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamzolkina, O.V.; Danilov, V.S.; Egorov, N.S. On the nature of luciferase from the bioluminescent fungus Armillariella mellea. Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR 1983, 3, 750–752. (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Kamzolkina, O.V.; Bekker, Z.E.; Egorov, N.S. Luciferin-luciferase system of the mushroom Armillariella mellea. Biologicheskie Nauki 1984, 1, 73–77. (in Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.G.; Stevani, C.V. The enzymatic nature of fungal bioluminescence. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2009, 8, 1416–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.G.; Desjardin, D.E.; Perry, B.A.; Stevani, C.V. Evidence that a single bioluminescent system is shared by all known bioluminescent fugal lineages. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2012, 11, 848–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Kojima, S.; Maki, S.; Hirano, T.; Niwa, H. Bioluminescence characteristics of the fruiting body of Mycena chlorophos. Luminescence 2011, 26, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, S.; Fukushima, R.; Wada, N. Extraction and purification of a luminiferous substance from the luminous mushroom Mycena chlorophos. Biophysics 2012, 8, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaskova, Z.M.; Dörr, F.A.; Petushkov, V.N.; Purtov, K.V.; Tsarkova, A.S.; Rodionova, N.S.; Mineev, K.S.; Guglya, E.B.; Kotlobay, A.; Baleeva, N.S.; Baranov, M.S.; Arseniev, A.S.; Gitelson, J.I.; Lukyanov, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Kanie, S.; Pinto, E.; Di Mascio, P.; Waldenmaier, H.E.; Pereira, T.A.; Carvalho, R.P.; Oliveira, A.G.; Oba, Y.; Bastos, E.L.; Stevani, C.V.; Yampolsky, I.V. Mechanism and color modulation of fungal bioluminescence. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1602847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teranishi, K. Identification of possible light emitters in the gills of a bioluminescent fungus Mycena chlorophos. Luminescence 2016, 31, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teranishi, K. Bioluminescence and chemiluminescence abilities of trans-3-hydroxyhispidin on the luminous fungus Mycena chlorophos. Luminescence 2018, 33, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H. –M.; Lee, H.–H.; Lin, C.–Y.I.; Liu, Y.–C.; Lu, M.R.; Hsieh, J.–W.H.; Chang, C.–C.; Wu, P.–H.; Lu, M.J.; Li, J.–Y.; Shang, G.; Lu, R.J.–H.; Nagy, L.G.; Chen, P.–Y.; Kao, H.–W.; Tsai, I.J. Mycena genomes resolve the evolution of fungal bioluminescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 31267–31277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitiouchkina, T.; Mishin, A.S.; Somermeyer, L.G.; Markina, N.M.; Chepurnyh, T.V.; Guglya, E.B.; Karataeva, T.A.; Palkina, K.A.; Shakhova, E.S.; Fakhranurova, L.I.; Chekova, S.V.; Tsarkova, A.S.; Golubev, Y.V.; Negrebetsky, V.V.; Dolgushin, S.A.; Shalaev, P.V.; Shlykov, D.; Melnik, O.A.; Shipunova, V.O.; Deyev, S.M.; Bubyrev, A.I.; Pushin, A.S.; Choob, V.V.; Dolgov, S.V.; Kondrashov, F.A.; Yampolsky, I.V; Sarkisyan, K.S. Plants with genetically encoded autoluminescence. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 944–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strack, R. Harnessing fungal bioluminescence (research highlights). Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sivinski, J. Arthropods attracted to luminous fungi. Psyche 1981, 88, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, P.; Delean, S.; Wood, T.; Austin, D. Bioluminescence in the ghost fungus Omphalotus nidiformis does not attract potential spore dispersing insects. IMA Fungus 2016, 7, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.G.; Stevani, C.V.; Waldenmaier, H.E.; Viviani, V.; Emerson, J.M.; Loros, J.J.; Dunlap, J.C. Circadian control sheds light on fungal bioluminescence. Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makihara, H.; Takeno, K.; Chûjô, M. Check list of the insects collected from Lampteromyces japonicus (Kawam.) Sing. on Mt. Hiko. Sci. Bull. Fac. Agr. Kyushu Univ. 1972, 26, 595–600, (in Japanese with English title). [Google Scholar]

| Taxon | Japanese name (*1) | Bioluminescence (references) (*3) |

|---|---|---|

| Family Mycenaceae | ||

| Mycena epipterygia (Scop.) S.F. Gray | Nameashi-také | Mycelium (Bothe, 1931 [85]; Wassink, 1978 [74], 1979 [45]; Desjardin et al., 2008 [46]) |

| Mycena galopus (Pers.) P. Kumm. | Nise-chishio-také | Mycelium (Bothe, 1931 [85]; Berliner, 1961 [86]; Wassink, 1978 [74], 1979 [45]; Treu & Agerer, 1990 [87]; Desjardin et al., 2008 [46]) |

| Mycena haematopus (Pers.) P. Kumm. | Chishio-také | Mycelium (Treu & Agerer, 1990 [87]; Bermudes et al., 1992 [88]; Desjardin et al., 2008 [46]): Basidiomes (weak) (Bermudes et al., 1992 [88]; Desjardin et al., 2008 [46]) |

| Mycena inclinata (Fr.) Quél. | Sembon-ashinaga-také | Mycelium (Wassink, 1978 [74], 1979 [45]; Desjardin et al., 2008 [46]) |

| Mycena olivaceomarginata (Massee) Massee | Fuchidori-kunugitaké (*3) | Mycelium (Wassink, 1978 [74], 1979 [45]; Desjardin et al., 2008 [46]) |

| Mycena pura (Pers.) P. Kumm. (*4) | Sakura-také | Mycelium (Treu & Agerer, 1990 [87]; Desjardin et al., 2008 [46]): gill of basidiome (Bothe, 1931 [85]; Wassink, 1978(?) [74], 1979(?) [45]) |

| Mycena rosea (Bull.) Gramberg | Sakurairo-také [66] | Mycelium (Treu & Agerer, 1990 [87]; Desjardin et al., 2008 [46]) |

| Mycena sanguinolenta (Alb. & Schwein.) P. Kumm. | Himé-chishio-také | Mycelium (Bothe, 1931 [85]; Wassink, 1978 [74], 1979 [45]; Desjardin et al., 2008 [46]) |

| Mycena stylobates (Pers.) P. Kumm. | Kyūban-také | Mycelium (Bothe, 1931 [85]; Wassink, 1978 [74], 1979 [45]; Desjardin et al., 2008 [46]) |

| Roridomyces roridus (Fr.) Rexer | Nunawa-také | Mycelium (Josserand, 1953 [89]; Wassink, 1978(?) [74], 1979(?) [45]; Desjardin et al., 2008 [46]) |

| Family Physalacriaceae | ||

| Armillaria fuscipes Petch (*5) | Ashiguro-narataké [90] | Mycelium (Wassink, 1978 [74], 1979 [45]; Berliner, 1961 [86]; Desjardin et al., 2008 [46]): Rhizomorph (Wassink, 1978 [74]) |

| Armillaria sinapina Berube & Dessur. | Hotei-narataké | Mycelium (Mihail, 2015 [91]) |

| Desarmillaria ectypa (Fr.) R.A. Koch & Aime | Yachihiro-hidataké | Mycelium, rhizomorph, basidiomes (Ainsworth, 2004 [92]) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).