Submitted:

29 April 2023

Posted:

04 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature review

2.1. Assessment of financial aspects of sustainable pension systems

2.2. Economic implications for increasing the soundness of pension reforms

2.3. Social underpinnings towards a more comprehensive social security system

3. Research methodology

3.1. Empirical models construction and specifications

3.2. Dependent variables

3.3. Independent variables

3.4. Control variables

3.5. Data sample description, sources, and specifications

4. Empirical results

4.1. Descriptive statistics analysis

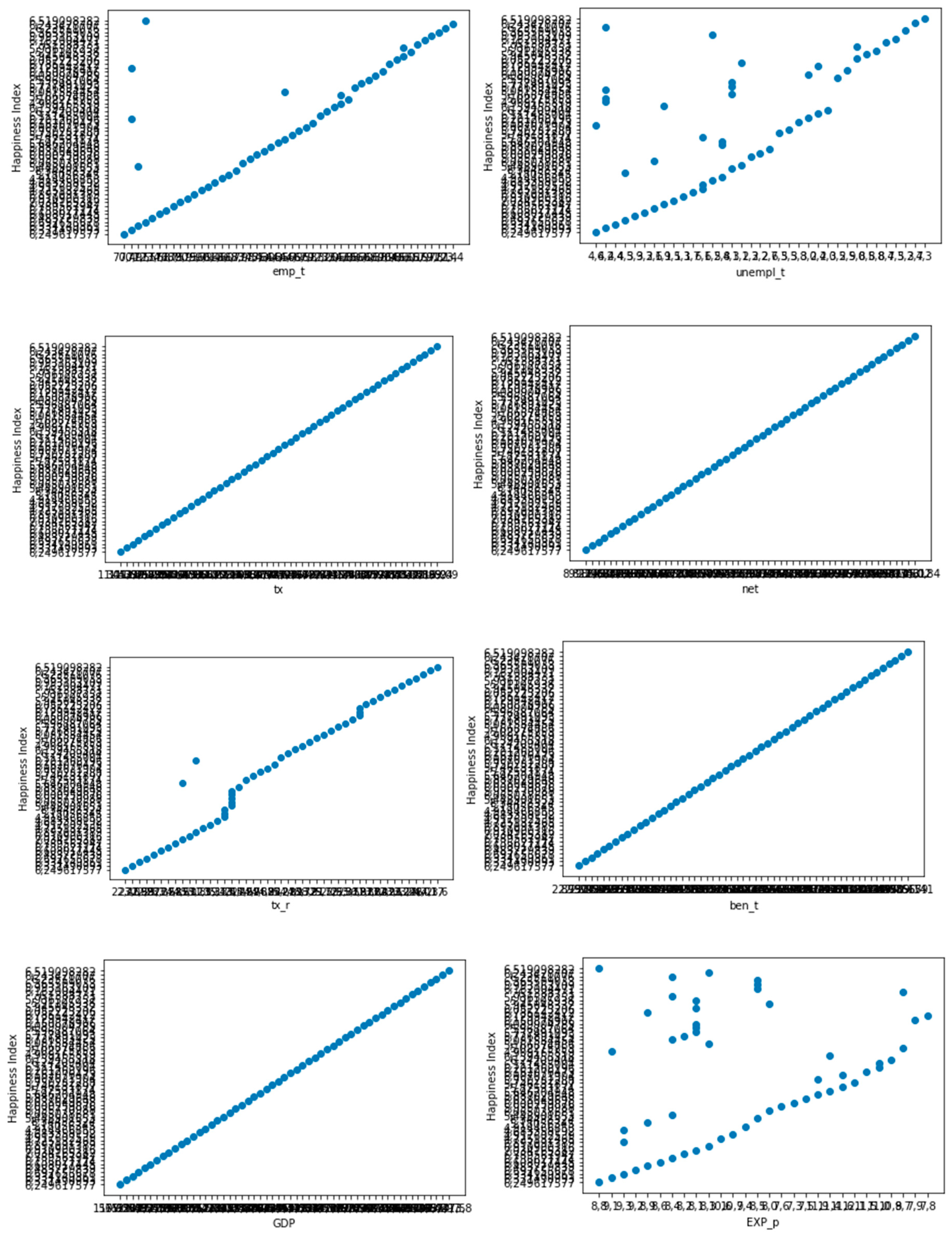

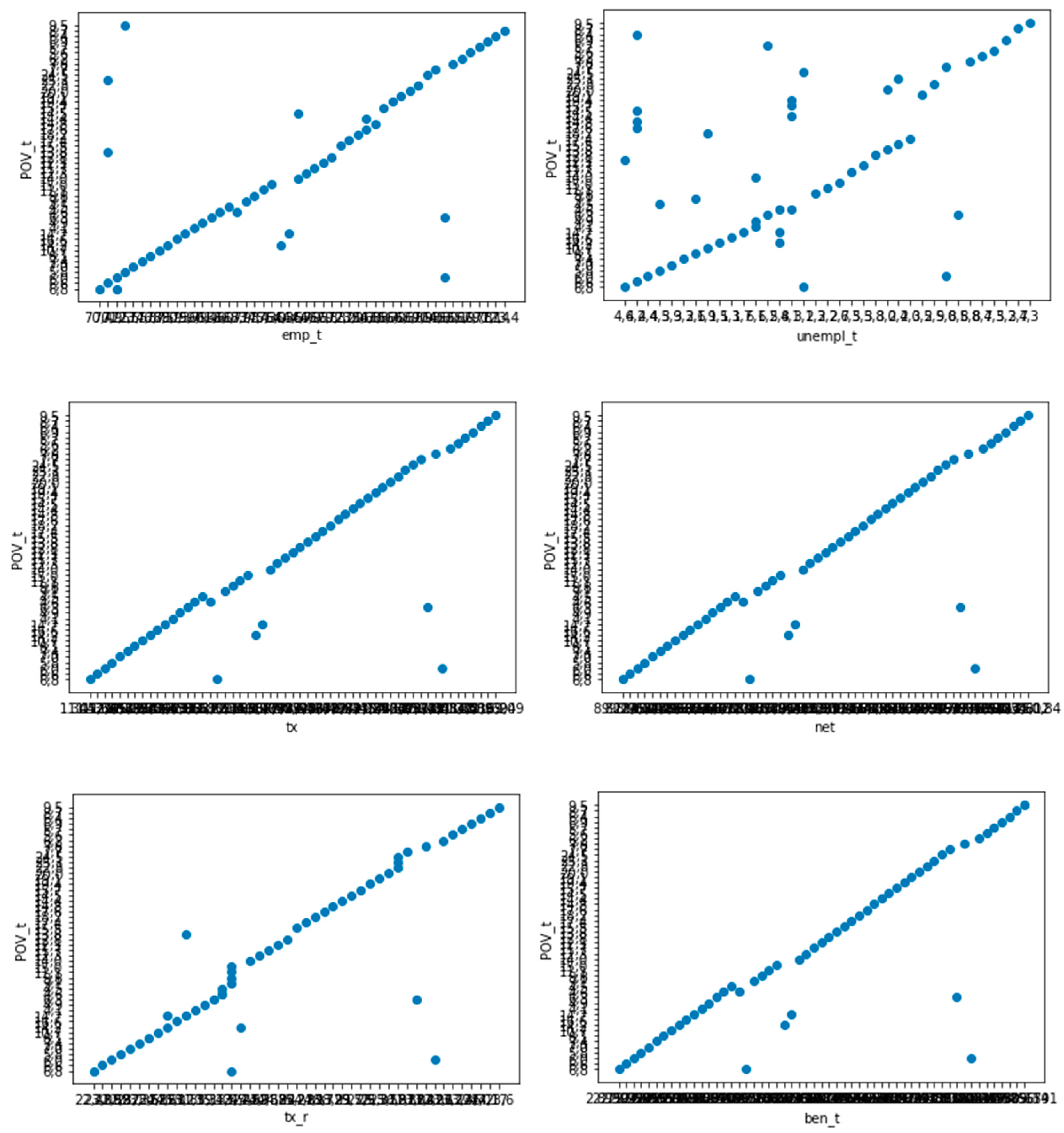

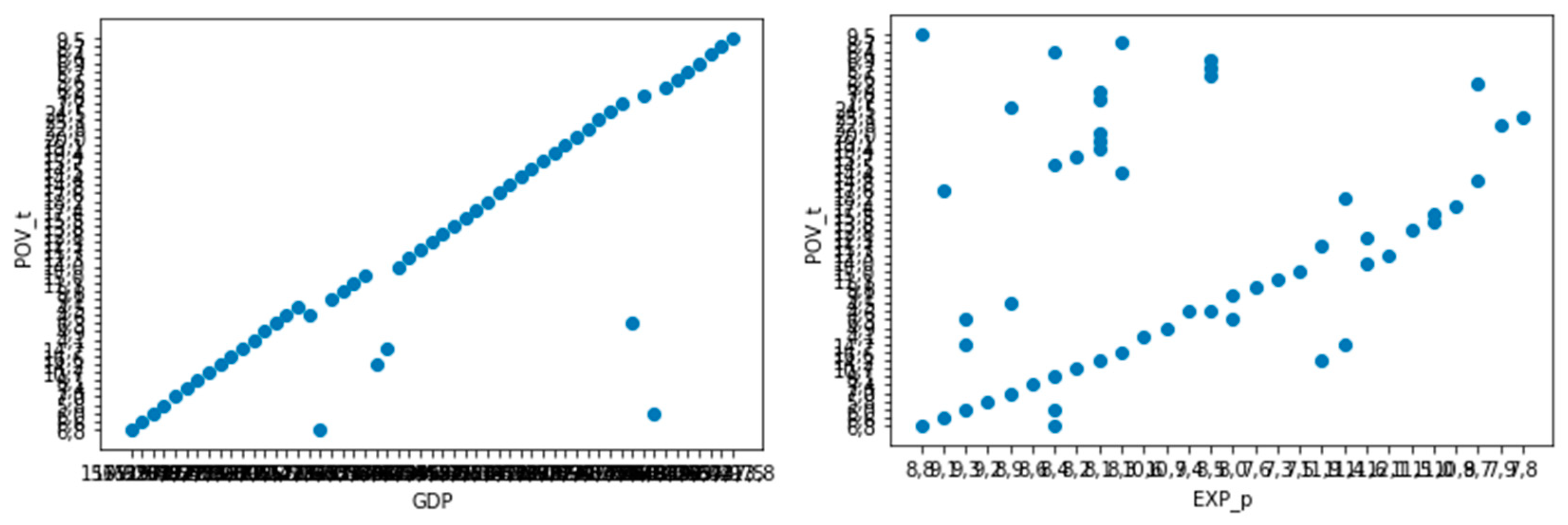

4.2. Plotting charts between the complex relationship of HDI, Happiness index, Poverty, and macroeconomic variables

4.3. Regression results

4.4. Robustness tests

5. Discussion and recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/9814.

- Chen, X.; Eggleston, K.; Sun, A. The impact of social pensions intergenerational relationships: Comparative evidence from China. The Journal of Economics and Ageing 2018, 12, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepngeno-Langat, G. van der Wielen, N. ; Evandrou, M.; Falkingham, J. Unravelling the wider benefits of social pensions: Secondary beneficiaries of the older persons cash transfer program in the slums of Nairobi. Journal of Aging Studies 2019, 51, 100818. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, K.; Scharf, T.; Van Regenmortel, S.; Wanka, A. (Eds.) Social Exclusion in Later Life - Interdisciplinary and Policy Perspectives. Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2021.

- Lee, K. Old-age poverty in a pension latecomer: The impact of basic pension expansions in South Korea. Soc Policy Adm. 2022, 56, 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Consumption and poverty of older Chinese: 2011–2020. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2022, 23, 100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romp, W.; Beetsma, R. OECD pension reform: The role of demographic trends and the business cycle. European Journal of Political Economy, 2022, 102280. [CrossRef]

- OECD 2021. Pensions at a Glance 2021: OECD and G20 Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, K. Recent pension reforms in Europe: More challenges, new directions. An overview,. Soc Policy Adm 2021, 55, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbinghaus, B. Inequalities and poverty risks in old age across Europe: The double-edged income effect of pension systems. Soc Policy Adm. 2021, 55, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerhout, E.; Meijdam, L.; Ponds, E.; Bonenkamp, J. Should we revive PAYG? On the optimal pension system in view of current economic trends, European Economic Review 2022, 148, 104227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronski, M. The impact of social security wealth on the distribution of wealth in the European Union. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2023, 24, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.C.; Tanaka, A.; Wuc, P.S. Shifting from pay-as-you-go to individual retirement accounts: A path to a sustainable pension system. Journal of Macroeconomics 2021, 69, 103329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laub, N.; Hagist, C. Pension and Intergenerational Balance: A case study of Norway, Poland and Germany using Generational Accounting. Intergenerational Justice Review 2017, 2, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosig, M.; Hinrichs, K. The “Great Recession” and Pension Policy Change in European Countries. In Nullmeier, F.; González de Reufels, D.; Obinger, H. (Eds.), International Impacts on Social Policy Short Histories in Global Perspective, Springer Nature Switzerland AG. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chybalski, F.; Marcinkiewicz, E. The Replacement Rate: An Imperfect Indicator of Pension Adequacy in Cross-Country Analyses. Soc Indic Res 2016, 126, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomen, M.; Wicht, L. Pension systems and the current account: An empirical exploration. Journal of International Money and Finance 2022, 120, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Németh, A.O.; Németh, P.; Vékás, P. Demographics, Labour Market, and Pension Sustainability in Hungary. Society and Economy 2019, 41, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, S.; Moscarola, F.C.; Figari, F.; Gandullia, L. Size and distributional pattern of pension-related tax expenditures in European countries. International Tax and Public Finance 2020, 27, 1287–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, A.F.; Sahlian, D.N.; Nicoara, S.A.; Sgardea, F.M.; Vuta, M. Economic Freedom and Government Quality - Influence Factors for Social Insurance Budgets Sustainability in Central and Eastern European Countries. Economic Computation and Economic Cybernetics Studies and Research, 2022, 56, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudrna, G.; Tran, C.; Woodland, A. Sustainable and equitable pensions with means testing in aging economies. European Economic Review 2022, 141, 103947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ștefan, G.M. A brief analysis of the administration costs of national social protection systems in EU member states. Procedia Economics and Finance 2015, 30, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristescu, A. The Impact of the Aging Population on the Sustainability of Public Finances. Romanian Journal of Regional Science 2019, 13, 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dumiter, F.C.; Jimon, S.A. Public Pension Systems’ Financial Sustainability in Central and Eastern European Countries. In Fotea, S.L.; Fotea, I.S., Ed.; Văduva, S. (Eds.), Navigating Through the Crisis: Business, Technological and Ethical Considerations The 2020 Annual Griffiths School of Management and IT Conference (GSMAC), Vol 2, Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotschedl, J. Selected factors affecting the sustainability of the PAYG pension system. Procedia Economics and Finance 2015, 30, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancia, F.; Russo, A. Public Education And Pensions In Democracy: A Political Economy Theory. Journal of the European Economic Association 2016, 14, 1038–1073 http://wwwjstororg/stable/43965335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, B.; Christl, M.; De Poli, S. Public redistribution in Europe: Between generations or income groups? . The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2023, 24, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, A. Ageing with Dignity: Old-Age Pension Schemes from the Perspective of the Right to Social Security Under ICESCR. Human Rights Review 2014, 15, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Ortiz, J. Social security and retirement across the OECD. Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control 2014, 47, 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halaskova, R. Structure of General Government Expenditure on Social Protection in the EU Member States. Montenegrin Journal of Economics 2018, 14, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.J. Saving public pensions: Labor migration effects on pension systems in European countries. The Social Science Journal 2013, 50, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenge, R.; Peglow, F. Decomposition of demographic effects on the german pension system. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2018, 12, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimon, S.A.; Dumiter, F.C.; Baltes, N. Financial Sustainability of Pension Systems Empirical Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Di Liddo, G. Immigration and PAYG pension systems in the presence of increasing life expectancy. Economics Letters 2018, 162, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T. Fiscal competition and state pension reforms, Public Budgeting & Finance 2022, 42, 41–70. [CrossRef]

- Olivera, J. The distribution of pension wealth in Europe. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2019, 13, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haan, P.; Prowse, V. Longevity, life-cycle behavior and pension reform. MPRA Paper No. 39282. 2012. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/39282/.

- Cipriani, G.P. Aging, Retirement, and Pay-As-You-Go Pensions. Macroeconomic Dynamics 2018, 22, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heer, B.; Trede, M. Age-specific entrepreneurship and PAYG: Public pensions in Germany. Journal of Macroeconomics 2023, 75, 103488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieppe, A.; Guarda, P. (Eds.) Occasional Paper Series: Public debt, population ageing and medium-term growth. Occasional Paper No 165, European Central Bank, 2015.

- Jun, H. Social security and retirement in fast-aging middle-income countries: Evidence from Korea. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2020, 17, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Marcos, V.; Bethencourt, C. The effect of public pensions on women’s labor market participation over a full life cycle. Quantitative Economics 2018, 9, 707–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkstedt, D.; Backhans, M.; Lundin, A.; Allebeck, P.; Hemmingsson, T. Do working conditions explain the increased risks of disability pension among men and women with low education? A follow-up of Swedish cohorts. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 2014, 50, 483–492 http://wwwjstororg/stable/43188047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundstrup, E.; Hansen, Å.M.; Mortensen, E.L.; et al. Retrospectively assessed psychosocial working conditions as predictors of prospectively assessed sickness absence and disability pension among older workers. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staubli, S.; Zweimüller, J. Does raising the early retirement age increase employment of older workers? . Journal of Public Economics 2013, 108, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engels, B.; Geyer, J.; Haan, P. Pension incentives and early retirement. Labour Economics 2017, 47, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Fertility and unemployment in a social security system. Economics Letters 2015, 133, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, O.S.; Clark, R.L.; Lusardi, A. Income trajectories in later life: Longitudinal evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2022, 22, 100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xinbang, C.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. An investigation of whether pensions increase consumption: Evidence from family portfolios. Finance Research Letters 2022, 47, 102591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammeraat, E. The relationship between different social expenditure schemes and poverty, inequality and economic growth. International Social Security Review 2020, 73, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, N.B.; Zamarro, G. Retirement effects on health in Europe. Journal of Health Economics 2011, 30, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibich, P. Understanding the effect of retirement on health: Mechanisms and heterogeneity. Journal of Health Economics 2015, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z. The health implications of social pensions: Evidence from China’s new rural pension scheme. Journal of Comparative Economics 2018, 46, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, T.; Buscha, S.H. Does money relieve depression? Evidence from social pension expansions in China. Social Science & Medicine 2019, 220, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, T.Y. What are the effects of expanding social pension on health? Evidence from the Basic Pension in South Korea. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2021, 18, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostert, C.M.; Mackay, D.; Awiti, A.; Kumar, M.; Merali, Z. Does social pension buy improved mental health and mortality outcomes for senior citizens? Evidence from South Africa’s 2008 pension reform. Preventive Medicine Reports 2022, 30, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herl, C.R.; Kabudula, K. , Kahn, K.; Tollman, S.; Canning, D. Pension exposure and health: Evidence from a longitudinal study in South Africa. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2022, 23, 100411. [CrossRef]

- Fe, E.; Hollingsworth, B. Short- and long-run estimates of the local effects of retirement on health. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 2016, A179, 1051–1067. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44682196.

- Heller-Sahlgren, G. Retirement blues. Journal of Health Economics 2017, 54, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, M.D.; Moore, T.J. The mortality effects of retirement: Evidence from Social Security eligibility at age 62. Journal of Public Economics 2018, 157, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrino, L.; Glaser, K.; Avendano, M. Later retirement, job strain, and health: Evidence from the new State Pension age in the United Kingdom. Health Economics 2020, 29, 891–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barschkett, M.; Geyer, J.; Haan, P.; Hammerschmid, A. The effects of an increase in the retirement age on health—Evidence from administrative data. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2022, 23, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, M.P.; Dass, A.R.; Laporte, A. The effect of post-retirement employment on health. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2020, 17, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallberg, D.; Johansson, P.; Josephson, M. Is an early retirement offer good for your health? Quasi-experimental evidence from the army. Journal of Health Economics 2015, 44, 274–285 101016/jjhealeco201509006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Krumins, J.; Berzins, A.; Dahs, A.; Ponomarjova, D. Healthy and Active Pre-Retirement and Retirement Ages: Elderly Inequality in Latvia. 11th International scientific conference „New Challenges of Economic and Business Development – 2019: Incentives for Sustainable Economic Growth” Proceedings, 2019. 463-475. ISBN 978-9934-18-428-4.

- Kang, J.Y.; Park, S.; Ahn, S. The effect of social pension on consumption among older adults in Korea. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2022, 22, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.J. G, Fraikin, A. L. The old-age pension household replacement rate in Belgium. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing 2022, 23, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I. The Effect of Pension on the Optimized Life Expectancy and Lifetime Utility Level, MPRA Paper No. 41374. 2012. Available online: http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/41374/.

- Ju, Y.J.; Han, K.T.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, J.E.; Choi, J.W.; Hyun, I.S.; Park, E.C. Quality of life and national pension receipt after retirement among older adults. Geriatrics and Gerontology International 2017, 17, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z. The health implications of social pensions: Evidence from China’s new rural pension scheme. Journal of Comparative Economics 2018, 46, 53–77 https://wwwjstororg/stable/48699023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, R.; Lopez – Rodriguez, F.; Tejero, A. Interests and values. Changes in satisfaction with public pensions and healthcare in Spain before the Great Recession. Espanola de Investigationes Sociologicas 2023, 181, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabar, R.; Kalwij, A. State pension eligibility age and retirement behavior: evidence from the United Kingdom household longitudinal study. Network for Studies on Pensions, Ageing, and Retirement – Academic Series 2023, 10, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Brunello, G.; De Paola, M.; Rocco, L. Pension reforms, longer working horizons, and absence from work. IZA Institute of Labor Economics 2023, 15871, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al–Hassan, H.; Devolder, P. Stochastic modelization of hybrid public pension plans (PAYG) under demographic risks with application to the Belgian case. LIDAM Discussion Paper 2022, 42, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Safaralievich, M.B. Efficiency of pension systems. International Journal of Business Diplomacy and Economy 2022, 1, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Aubry, J.P. Public pensions investment update: have alternatives helped or hurt? Center for Retirement and research at Boston College 2022, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Baurin, A.; Hindriks, J. Intergenerational consequences of gradual pension reforms. European Journal of Political Economy 2022, 102336, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romp, W.; Beetsma, R. OECD pension reform: The role of demographic trends and business cycle. European Journal of Political Economy 2022, 102280, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.; Maher, C. Fiscal condition, institutional constraints, and public pension contribution: are pension contribution shortfalls fiscal illusion? Public Budgeting & Finance 2022, 42, 93–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, I. The binary path of risks in pension systems and political pressure. World Review of Political Economy 2021, 12, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Research method | Sample | Results and main conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ștefan (2015) | Panel data model | 28 EU countries | The number of taxpayers, the number of unemployed populations, and the real GDP growth rate influence social expenditures. |

| Chybalski & Marcinkiewicz (2016) | Spearman’s rank correlation Panel regression models |

EU countries | The financial adequacy of pension systems is not broadly measured by the replacement rate. |

| Laub & Hagist (2017) | Generational Accounting | Norway, Poland, Germany | Pension systems reforms determined a more intergenerationally balanced pension system and the debt to be paid by future generations was reduced. |

| Németh, Németh & Vékás (2019) | Scenario technique | Hungary | Social contribution payments and pension benefits are the main factors that influence the sustainability of the pension system. |

| Cristescu (2019) | Panel data model | EU countries | Retirement age, contributory period, and income are the main factors that enhance pension sustainability. |

| Barrios et al. (2020) | Microsimulation model | EU countries | Pension-related tax expenditures have a sizeable impact on revenue (up to + 26% in Romania). |

| Lin, Tanaka & Wuc (2021) | Multi-period over-lapping generation model | Taiwan | PAYG pension systems have a positive welfare effect but place a larger burden on future generations. |

| Kudrna, Tran & Woodland (2022) | Overlapping generations model |

Australia | Means-tested pension systems with fiscal and a redistributive stabilization device could be sustainable in the long run. |

| Westerhout et al. (2022) | Numerical simulation experiments | If the low average rate of economic growth, the low average capital market rate of return, the low volatility of economic growth and the high volatility of the capital market rate of return persist in the coming decades, the optimal size of PAYG should increase. |

|

| Dumiter & Jimon (2022) | Ordinary least squares regressions | Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Romania |

The expenditures with social protection are correlated with demographic and labor market features. |

| Koomen & Wicht (2022) | Overlapping generations model |

49 countries | There is a positive significant relationship between fully-funded pension system and current account balance. |

| Brosig & Hinrichs (2022) | EU countries | Pension reforms enacted since 2008 have improved the financial sustainability, but in many cases also endangered the benefits’ adequacy. | |

| Popa et al. (2022) | Ordinary least squares regressions | Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Romania |

Economic freedom, quality of public services, the government's capacity to draw up and implement sound and stable policies and the control of corruption positively influences social budget revenues. |

| Hammer, Christl & De Poli (2023) | Quartile analysis | 27 EU countries and the UK | The old-age-oriented countries provide generous benefits to pensioners (most Southern European countries). The low-income-oriented countries support low income population (Northern European countries). |

| Wronski (2023) | Correlation analysis | 19 EU countries | Social security wealth reduces wealth inequality both at the country level and in the whole European Union. |

| Author | Research method | Sample | Results and main conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Falkstedt et al. (2014) | Cox proportional-hazards regression | 9985 men and 9730 women from Sweden | Working conditions explain the increased rate of disability pension among people with lower education. |

| Wang (2015) | Overlapping generations model | The pension system may increase fertility and decrease unemployment. | |

| Dieppe & Guarda (2015) | General equilibrium | Portugal, Luxembourg Finland | To coop the demographic shocks the reforms must encourage labor force participation. |

| Engels, Geyer & Haan (2017) | Multivariate analysis | Germany | Increasing the retirement age favors unemployment. |

| Cipriani (2018) | Overlapping generations model | Aging produces an increase in retirement age. | |

| Fenge & Peglow (2018) | Simulation model and long run projections |

Germany | The increase in net migration and fertility has a positive impact on the pension system sustainability, but cannot counteract the pressure of life expectancy growth. |

| Sanchez-Marcos & Bethencourt (2018) | Partial equilibrium life-cycle model |

USA | The elimination of spousal and survivor benefits can increase the female labor supply. |

| Olivera (2019) | Comparative analysis of socio-economic status life tables | 26 EU countries | Socio-economic status inequalities in mortality and tertiary education are less important in explaining pension wealth inequality. |

| Jun (2020) | Probit regression model | South Korea | A greater utility perceived by workers from continued work due to additional earnings and pension wealth gains will determine the postponement of retirement. |

| Cammeraat (2020) | OLS and 2SLS regression models |

22 EU countries | Public social expenditure is reducing poverty and inequality, but only expenditure on housing determines the GDP growth. |

| Jimon, Dumiter & Baltes (2021) | OLS regression models | Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Romania |

Pension system sustainability is related to socio-economic and medical characteristics of population. |

| Mitchell, Clark & Lusardi (2022) | Multinomial Logit regression model Quartile analysis |

USA | The real incomes of retirees remained relatively stable. |

| Xinbang et al. (2022) | Regression analysis | China | The pension system assures the basic life after retirement and have a positive influence on consumption level. |

| Hoang (2022) | EHA and the IV-probit model | 50 states | Interstate migration determines states to adopt pension reform and different actions to improve efficiency. |

| Heer & Trede (2023) | OLG model | Germany | The sustainability of the pension system can be achieved only be the increase of the retirement age up to 70 years. |

| Author | Research method | Sample | Results and main conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hallberg, Johansson & Josephson (2015) | OLS Two-stage least-squares |

Sweden | Early retirement can reduce the mortality risk. |

| Eibich (2015) | Regression Discontinuity Design | Germany | Retirement improves subjective health status and mental health. |

| Fe & Hollingsworth (2016) | Regression discontinuity design (RDD) Panel data model |

11 331 UK male residents | Retirement favors sedentarism and social isolation, indirectly negatively affecting the health of retirees. |

| Ju et al. (2017) | Generalized estimating equations model | Korea | Pension benefits have a positive influence on satisfaction and quality of life. |

| Heller-Sahlgren (2017) | Regression-discontinuity design (RDD) 2SLS model |

10 European countries | Retirement has a large negative longer-term impact on mental health. |

| Cheng et al. (2018) | Fixed-effect model with instrumental variable correction. | China | Pensions have a positive effect on the physical health and cognitive function of the elderly. |

| Chena, Wang & Buscha (2019) | Two-stage least-squares | China | Pension provisions have a positive impact on mental well-being and decrease depressive symptoms. |

| Carrino, Glaser & Avendano (2020) | OLS regressions | UK | The growth of retirement age increases the probability of depressive symptoms among women in a lower occupational grade. |

| Silver, Dass & Laporte (2020) | Conditional Mixed Process (CMP) model | USA |

post-retirement employment has a positive effect on self-assessed health and depressive symptoms for both women and men. |

| Pak (2021) | Difference-in-differences models | South Korea | Pension reduces depressive symptoms. |

| Kang, Park & Ahn (2022) | Linear regression models with the fixed-effect model |

South Korea | The social pension reduces poverty among older adults and improved food, clothing and healthcare products consumption. |

| Brown & Fraikin (2022) | Discrete-time logistic duration model Microsimulation model |

Belgium | The pension replacement rate plays an important role in decreasing poverty. |

| Barschkett et al. (2022) | Difference-in-Differences approach | Germany | Increasing the retirement age has a negative effect on health. |

| Mostert et al. (2022) | Two-stage Least Squared Model | South Africa | Pension distributions improve mental health outcomes of the elderly and prevent depression, traumatic stress, and death. |

| Herl et al. (2023) | OLS regressions | South Africa | Pension is associated with better physical health. |

| Variables | Construction mechanism | Unit/Scale | Sources |

| Dependent variable | |||

| Human Development Index (HDI) | Three key dimensions: A long and healthy life; 2. Access to education; 3. A decent standard of living. |

Three measures: Life expectancy. Years of schooling of children at school entry age and mean years of schooling of the adult population. GNI per capita is adjusted for the price level of the country. |

Human Development Reports – Human Development Index – Country Insights – Database. |

| Happiness Index (HPI) | Three main indicators: 1. Life evaluations. 2. Positive emotions. 3. Negative emotions. |

Variables included: Happiness score or subjective well-being; GDP per capita; Healthy Life Expectancy, Social Support; Freedom to make life choices; Generosity; Corruption Perception; Positive affect; Negative affect; GINI of household income; GINI index; Institutional trust. | The World Happiness Report – Country Rankings – Database. |

| Poverty – total (POV_t) | At risk poverty rate – 65 years over, %. | Cut-off point: 60% of median equivalised income after social transfers | Eurostat Database. |

| Independent variables | |||

| Employment (emp_t) | Employment and activity by sex and age, from 20 to 64 years. | Percentage of total population. | Eurostat Database. |

| Unemployment (unempl_t) | Unemployment by sex and age, from 15 to 74 years. | Percentage of total population. | Eurostat Database. |

| Beneficiaries (ben_t) | Pension beneficiaries at 31st december. | Number of people. | Eurostat Database. |

| Control variables | |||

| Taxes (tx) | Taxes. | Single person without children earning 100% of the average earning, euro. | Eurostat Database. |

| Net earnings (net) | Net earnings. | Single person without children earning 100% of the average earning, euro. | Eurostat Database. |

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | Gross Domestic Product at market prices. | Current prices, million euro. | Eurostat Database. |

| Expenditures on Pensions (EXP_p) | Expenditures on pensions. | Percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). | Eurostat Database. |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDI | 55 | 0.8518 | 0.0256 | 0.8050 | 0.8970 |

| HPI | 55 | 5.9710 | 0.5743 | 4.6833 | 7.0341 |

| POV_t | 55 | 17.6954 | 12.4004 | 5.2909 | 40.5774 |

| emp_t | 55 | 69.4436 | 4.9782 | 59.9000 | 80.3000 |

| unempl_t | 55 | 4.3781 | 1.9918 | 1.3000 | 9.0000 |

| tx | 55 | 4.8054 | 2.2255 | 1.3000 | 10.1000 |

| net | 55 | 1225.14 | 460.8173 | 608.41 | 2242.43 |

| ben_t | 55 | 27.0390 | 4.6877 | 21.8800 | 36.9100 |

| GDP | 55 | 7.6072 | 4.0521 | 2.0000 | 17.6000 |

| EXP_p | 55 | 19.6931 | 13.0319 | 6.8764 | 53.2504 |

| HDI | HPI | POV_t | |||||||

| OLS | FE | RE | OLS | FE | RE | OLS | FE | RE | |

| c | 0.5416* (12.54) |

0.8033* (22.84) |

0.6894* (22.62) |

-2.8972 (-1.90) |

0.7606 (0.40) |

-2.3649 (-1.46) |

1.2000 (8.24) |

4.2446 (6.50) |

4.6888 (8.28) |

| emp_t | 0.5416* (7.71) |

0.0004*** (1.03) |

0.0017*** (4.36) |

0.1302* (7.07) |

0.0859** (3.68) |

0.1031* (4.94) |

-1.3276 (-7.52) |

-3.3044 (-4.03) |

-3.8955 (-5.31) |

| unempl_t | 0.0108*** (2.39) |

-0.0045*** (-1.3656) |

0.0001*** (0.06) |

0.3305* (2.0769) |

0.4818* (2.73) |

0.35* (2.28) |

1.8241 (1.19) |

-2.7229 (-0.43) |

-6.3543 (-1.17) |

| tx | -0.0057*** (-1.26) |

0.0045*** (1.59) |

0.0005*** (0.21) |

-0.1899* (-1.20) |

-0.0807** (-0.53) |

-0.1899* (-1.38) |

-3.788 (-2.49) |

-2.6955 (0.50) |

-1.1959 (-0.24) |

| net | 9.080 (2.34) |

-4.1300 (-0.83) |

4.7900 (1.35) |

-0.0002*** (-1.74) |

-0.0006*** (-2.58) |

-3.9600 (-0.21) |

-386.61 (-2.95) |

168.44 (1.84) |

141.98 (2.15) |

| ben_t | -0.0002*** (-0.69) |

0.0003*** (1.11) |

0.0006*** (2.47) |

-0.0238** (-2.17) |

-0.0339** (-2.08) |

5.7400 (0.00) |

-4.4457 (-4.22) |

3636.89 (0.63) |

2779.12 (0.61) |

| GDP | -0.0024** (-5.54) |

-0.0002*** (-0.45) |

-0.0009*** (-2.92) |

0.0379** (2.44) |

-0.0097*** (-0.40) |

0.0404** (2.37) |

5.5477 (3.73) |

-4897.73 (-0.57) |

7567.88 (1.26) |

| EXP_p | 1.1900 (10.69) |

6.1100 (1.97) |

1.2200 (5.57) |

-3.0900 (-0.78) |

-3.38 (-2.065) |

1.4100 (1.22) |

6.41 (17.06) |

-1.0109 (-1.76) |

-0.9396* (-2.31) |

| R-Squared | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| F / Wald | 115.74 | 42.65 | 173.25 | 42.89 | 31.13 | 35.64 | 245.07 | 1232.67 | 2349.63 |

| Hausman (chi-squared test) | 51.48 | 39.66 | 14.62 | ||||||

| HDI | HPI | POV_t | |||||||

| 2SLS | FE | RE | 2SLS | FE | RE | 2SLS | FE | RE | |

| c | 0.5232* (0.05) |

0.8265* (22.66) |

0.6948* (21.53) |

-1.8492 (-1.09) |

1.8956 (0.88) |

-1.5710 (-0.82) |

12.7645 (7.84) |

35.7341 (5.57) |

3.9582 (6.82) |

| emp_t | 0.0042** (0.00) |

0.0003*** (0.73) |

0.0017** (4.49) |

0.1190* (5.79) |

0.0740** (2.95) |

0.0931** (3.95) |

-14.2689 (-7.22) |

-2.6091 (-3.48) |

-32.1990 (-4.46) |

| unempl_t | 0.0120** (2.28) |

-0.0042** (-1.44) |

-0.0032** (-1.05) |

0.3926* (2.23) |

0.4925* (2.84) |

0.4587* (2.54) |

2.0734 (1.23) |

7496.14 (0.14) |

24.6340 (0.45) |

| tx | -0.0065** (-1.22) |

0.0051** (1.97) |

0.0032** (1.20) |

-0.2713* (-1.53) |

-0.0958** (-0.62) |

-0.3079* (-1.91) |

-41.0830 (-2.41) |

-52.973 (-1.15) |

-75.8880 (-1.56) |

| net | 6.7900 (1.55) |

-7.2200 (-1.45) |

-2.7200 (-0.07) |

-0.0002*** (-1.68) |

-0.0007*** (-2.51) |

2.1700 (0.01) |

287.8194 (-2.06) |

207.3621 (2.37) |

239.9830 (3.71) |

| ben_t | -0.0001*** (-0.31) |

0.0001*** (0.56) |

0.0007*** (3.12) |

-0.0300** (-2.55) |

-0.0415** (-2.22) |

-0.0022** (-0.14) |

-5.0358 (-4.45) |

5883.85 (1.05) |

5217.13 (1.15) |

| GDP | -0.0024** (-4.82) |

-0.0003*** (-0.73) |

-0.0006*** (-1.65) |

0.0497** (2.93) |

-0.0147** (-0.59) |

0.0440** (2.04) |

57.852 (3.55) |

-5130.07 (-0.68) |

-1092.22 (-0.16) |

| EXP_p | 1.1900 (9.74) |

2.8400 (0.97) |

7.5200 (3.31) |

-6.6500 (-1.64) |

-2.6500 (-1.55) |

1.3400 (1.00) |

6.3642 (16.33) |

-0.7698* (-1.50) |

-0.6624* (-1.64) |

| R-Squared | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| F / Wald | 101.90 | 229.57 | 178.05 | 39.94 | 29.48 | 35.35 | 266.51 | 1727.14 | 3765.63 |

| Variables |

Fischer – ADF Test | Fischer – PP Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | Constant and Trend | Constant | Constant and Trend | ||||||

| t-statistic | p-value | t-statistic | p-value | t-statistic | p-value | t-statistic | p-value | ||

| HDI HPI POV_t emp_t unempl_t tx net Level ben_t GDP EXP_p |

9.5694 | 0.4790 | 7.8969 | 0.6389 | 20.0191 | 0.0291** | 9.5168 | 0.4838 | |

| 2.7420 | 0.9869 | 18.8234 | 0.0310** | 2.5632 | 0.9899 | 34.6689 | 0.0001*** | ||

| 28.7379 | 0.0014*** | 38.6428 | 0.0000*** | 34.9735 | 0.0001*** | 24.0637 | 0.0074*** | ||

| 15.1847 | 0.1255 | 11.5510 | 0.3162 | 1.3255 | 0.9994 | 6.9875 | 0.7266 | ||

| 8.4898 | 0.5811 | 18.3128 | 0.0499* | 1.9580 | 0.9967 | 3.8324 | 0.9546 | ||

| 4.3499 | 0.9302 | 13.9888 | 0.1735 | 1.9360 | 0.9968 | 3.3913 | 0.9707 | ||

| 5.1912 | 0.8780 | 15.4392 | 0.1169 | 4.73210 | 0.9083 | 4.1237 | 0.9416 | ||

| 17.0063 | 0.0742* | 13.2886 | 0.2080 | 15.4451 | 0.1167 | 27.6844 | 0.0020*** | ||

| 0.5836 | 1.0000 | 8.9144 | 0.5402 | 1.3765 | 0.9993 | 18.1848 | 0.0519* | ||

| 1.7034 | 0.9981 | 10.3990 | 0.4062 | 0.6834 | 1.0000 | 3.6609 | 0.9614 | ||

| HDI HPI POV_t emp_t unempl_t tx net 1st ben_t dif. GDP EXP_p |

15.2430 | 0.1235 | 11.7226 | 0.3040 | 18.1665 | 0.0522 | 23.5285 | 0.0090*** | |

| 39.5550 | 0.0000*** | 24.7072 | 0.0059*** | 67.2140 | 0.0000*** | 57.4348 | 0.0000*** | ||

| 38.5202 | 0.0000*** | 41.6979 | 0.0000*** | 38.4722 | 0.0000*** | 46.6716 | 0.0000*** | ||

| 13.4754 | 0.1983 | 4.1970 | 0.9380 | 11.0193 | 0.3560 | 4.7504 | 0.9072 | ||

| 11.2192 | 0.3407 | 0.8773 | 0.9999 | 4.5178 | 0.9210 | 0.6392 | 1.0000 | ||

| 11.1324 | 0.3473 | 1.2184 | 0.9996 | 5.6176 | 0.8463 | 0.6280 | 1.0000 | ||

| 23.7911 | 0.0082*** | 12.9715 | 0.2253 | 19.4541 | 0.0349** | 21.2580 | 0.0194** | ||

| 36.6656 | 0.0001*** | 22.1274 | 0.0145** | 38.0651 | 0.0000*** | 35.7338 | 0.0001*** | ||

| 28.1533 | 0.0017*** | 24.4896 | 0.0064*** | 33.3038 | 0.0002*** | 30.1732 | 0.0008*** | ||

| 13.4747 | 0.1983 | 6.6705 | 0.7561 | 10.6732 | 0.3835 | 3.4748 | 0.9679 | ||

| HDI HPI POV_t emp_t unempl_t tx net 2nd ben_t dif. GDP EXP_p |

31.6277 | 0.0005*** | 16.7360 | 0.0804* | 41.7726 | 0.0000*** | 37.6193 | 0.0000*** | |

| 49.4573 | 0.0000*** | 26.4837 | 0.0031*** | 91.7182 | 0.0000*** | 77.3631 | 0.0000*** | ||

| 62.3122 | 0.0000*** | 31.1992 | 0.0005*** | 67.8915 | 0.0000*** | 52.3499 | 0.0000*** | ||

| 20.9090 | 0.0217** | 33.4272 | 0.0002*** | 23.2970 | 0.0097** | 45.4464 | 0.0000*** | ||

| 13.4145 | 0.2014 | 38.4734 | 0.0000*** | 14.2309 | 0.1627 | 51.8556 | 0.0000*** | ||

| 18.9492 | 0.0409** | 41.3270 | 0.0000*** | 17.1920 | 0.0702 | 45.2660 | 0.0000*** | ||

| 15.9526 | 0.1010 | 7.6899 | 0.6591 | 32.2941 | 0.0004*** | 17.0157 | 0.0740* | ||

| 25.9997 | 0.0037** | 21.8658 | 0.0158** | 53.9178 | 0.0000*** | 50.8666 | 0.0000*** | ||

| 42.5584 | 0.0000*** | 30.5120 | 0.0007*** | 51.0581 | 0.0000*** | 42.1172 | 0.0000*** | ||

| 15.1614 | 0.1263 | 5.8383 | 0.8287 | 15.5746 | 0.1125 | 8.2044 | 0.6098 | ||

| Variables |

statistic | p-value | Weighted statistic |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDI – emp_t HPI – unempl_t POV_t – tx net – ben_t GDP – EXP_p |

1.0169 | 0.1546 | 0.8736 | 0.1912 |

| 2.1952 | 0.0141 | 0.3297 | 0.3708 | |

| 1.3693 | 0.0854 | 1.1042 | 0.1347 | |

| -0.5733 | 0.7168 | -0.4098 | 0.6591 | |

| 5.5242 | 0.0000 | 1.7338 | 0.0415 |

| Coefficient | Std. error | t-statistic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADF | -2.5850 | 0.0049 | ||

| Resid (-1) | -0.5913 | 0.1413 | -4.1824 | 0.0001 |

| D(Resid (-1)) | 0.1571 | 0.1498 | 1.0490 | 0.3000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).