Submitted:

04 May 2023

Posted:

05 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

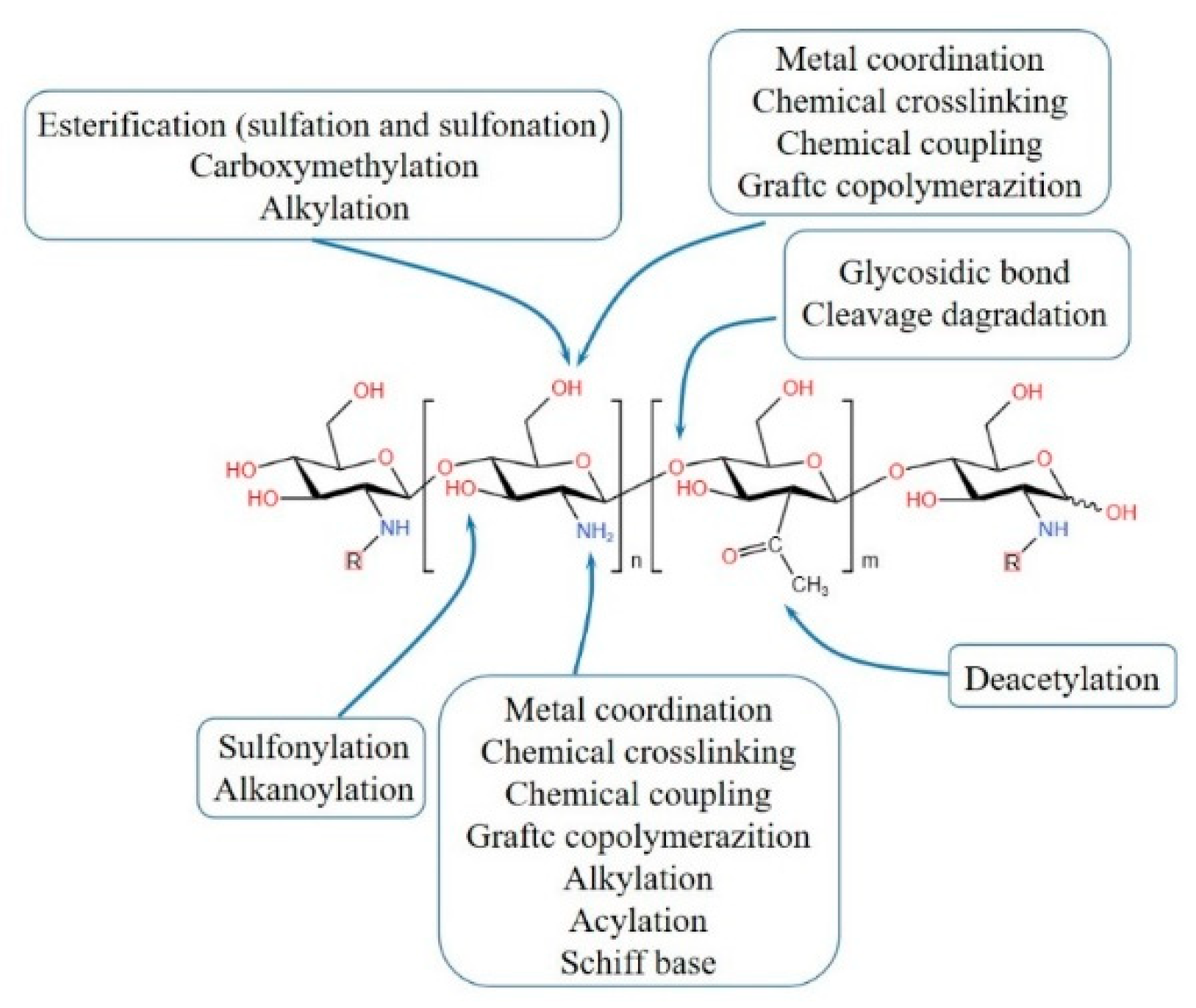

2. Synthesis methods of CBHs

2.1. Physical crosslinking CBHs

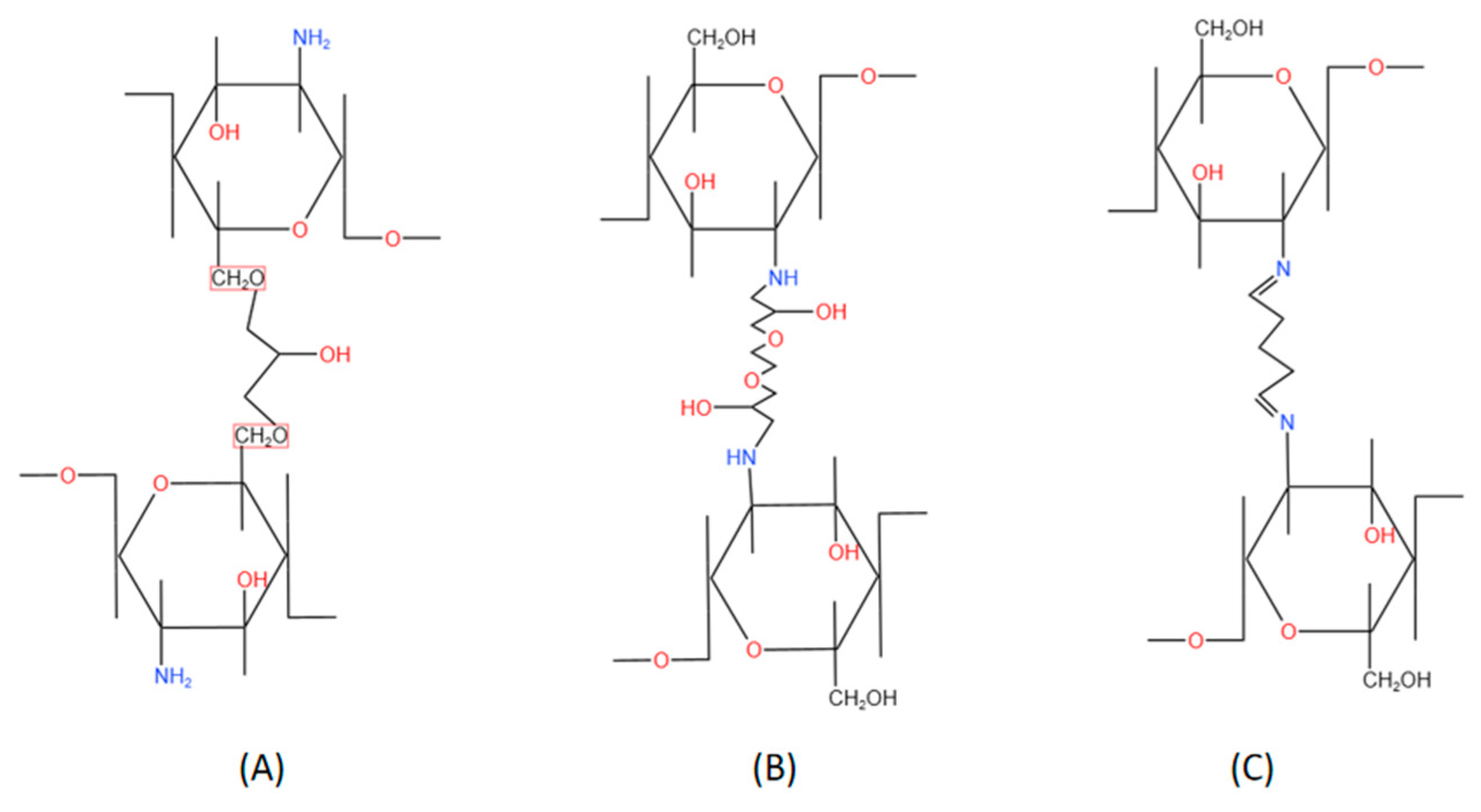

2.2. Chemical crosslinking CBHs

3. Characterization methods

3.1. Microstructure Analysis

3.2. Chemical interactions Analysis

3.3. Thermal Stability Analysis

3.4. Blood Compatibility Analysis

3.5. Mechanical Resistance Analysis

3.6. Antimicrobial Properties Analysis

3.7. Viscosity Analysis

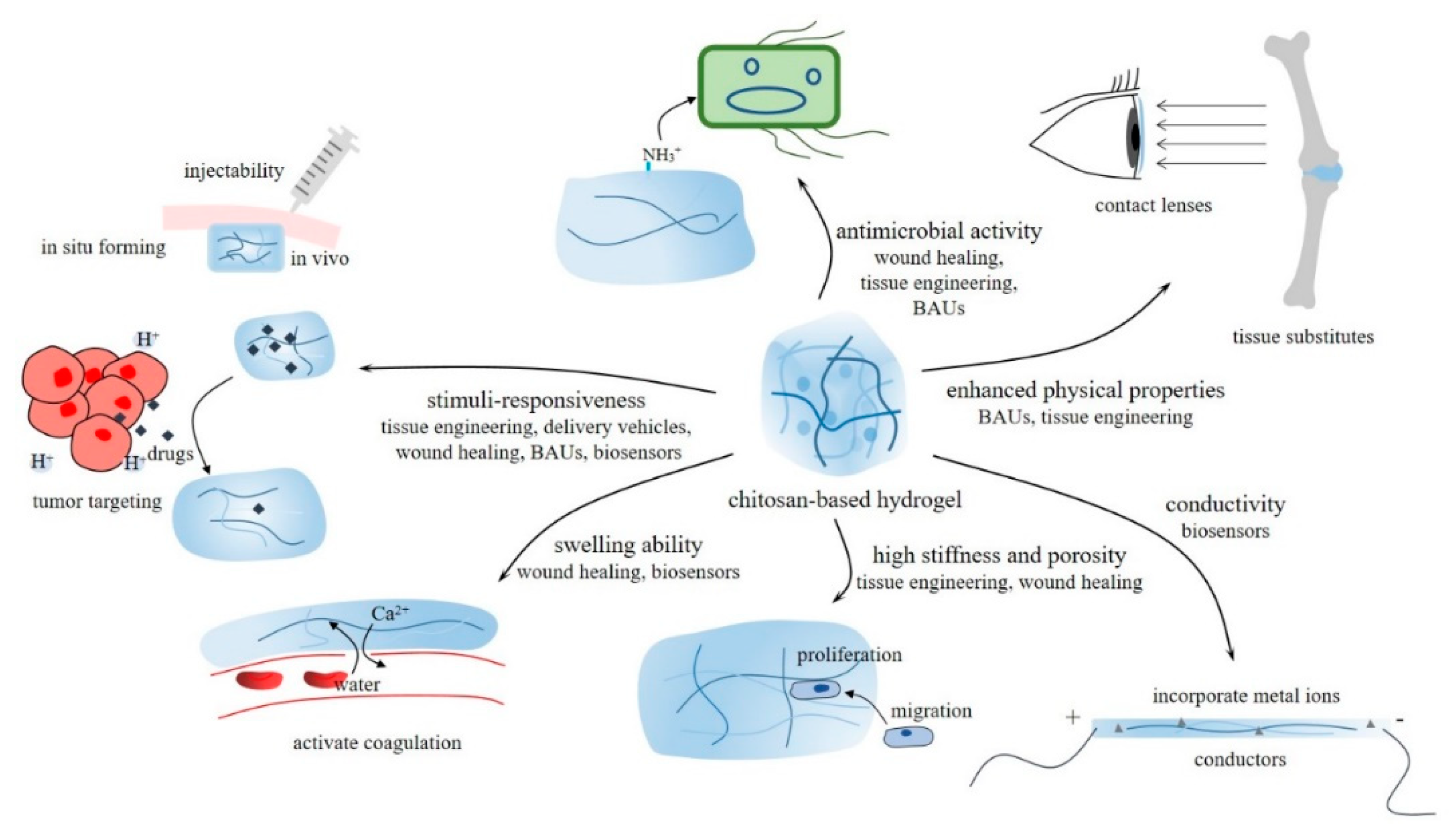

4. Properties and biomedical application of CBHs

4.1. Tissue engineering

4.1.1. Methods and techniques to implant

4.1.2. Microenvironment adjustment

4.1.3. Tissue regeneration

4.1.4. Biodegradation in vivo

4.2. Delivery vehicles

4.2.1. Drug release regulation and release kinetics

4.2.2. Loaded consignments

4.3. Wound healing

4.3.1. Hemostasis phase

4.3.2. Inflammation regulation phase

4.3.3. Fostering proliferation phase

4.4. Biocompatible auxiliary units (BAUs)

4.5. Molecular detection biosensors

4.5.1. Immobilization matrix

4.5.2. Responsive units

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grzybek, P.; Jakubski, Ł.; Dudek, G. Neat Chitosan Porous Materials: A Review of Preparation, Structure Characterization and Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dana, P.M.; Hallajzadeh, J.; Asemi, Z.; Mansournia, M.A.; Yousefi, B. Chitosan applications in studying and managing osteosarcoma. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 169, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, S. (.; Peters, L.M.; Mucalo, M.R. Chitosan: A review of sources and preparation methods. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 169, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razmi, F.A.; Ngadi, N.; Wong, S.; Inuwa, I.M.; Opotu, L.A. Kinetics, thermodynamics, isotherm and regeneration analysis of chitosan modified pandan adsorbent. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hack, M.E.A.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Shafi, M.E.; Zabermawi, N.M.; Arif, M.; Batiha, G.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; El-Hakim, Y.M.A.; Al-Sagheer, A.A. Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of chitosan and its derivatives and their applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 2726–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azmy, E.A.; Hashem, H.E.; Mohamed, E.A.; Negm, N.A. Synthesis, characterization, swelling and antimicrobial efficacies of chemically modified chitosan biopolymer. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 284, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Meng, Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhou, M.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, K. Chitosan Derivatives and Their Application in Biomedicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, E487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negm, N.A.; Hefni, H.H.; Abd-Elaal, A.A.; Badr, E.A.; Kana, M.T.A. Advancement on modification of chitosan biopolymer and its potential applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 152, 681–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Chan, H.-P.; Chung, T.-W.; Shu, C.-W.; Chuang, K.-P.; Duh, T.-H.; Yang, M.-H.; Tyan, Y.-C. Hydrogels: Properties and Applications in Biomedicine. Molecules 2022, 27, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, C.Y.; Falkman, P.; Risbo, J.; Cárdenas, M.; Medronho, B. Chitosan-dextran sulfate hydrogels as a potential carrier for probiotics. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 172, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellá, M.C.; Lima-Tenório, M.K.; Tenório-Neto, E.T.; Guilherme, M.R.; Muniz, E.C.; Rubira, A.F. Chitosan-based hydrogels: From preparation to biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 196, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jhiang, J.-S.; Wu, T.-H.; Chou, C.-J.; Chang, Y.; Huang, C.-J. Gel-like ionic complexes for antimicrobial, hemostatic and adhesive properties. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 2878–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, N.; Solaiman; Roy, C.K.; Firoz, S.H.; Foyez, T.; Imran, A.B. Role of ionic moieties in hydrogel networks to remove heavy metal ions from water. ACS omega 2020, 6, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, J.; Reist, M.; Mayer, J.; Felt, O.; Peppas, N.; Gurny, R. Structure and interactions in covalently and ionically crosslinked chitosan hydrogels for biomedical applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2004, 57, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Tiwari, S. RETRACTED: A review on biomacromolecular hydrogel classification and its applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Chen, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H. Freeze-thaw and solvent-exchange strategy to generate physically cross-linked organogels and hydrogels of curdlan with tunable mechanical properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 278, 119003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, N.; Gunn, J.; Zhang, M. Chitosan-based hydrogels for controlled, localized drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2010, 62, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vakili, M.; Rafatullah, M.; Salamatinia, B.; Abdullah, A.Z.; Ibrahim, M.H.; Tan, K.B.; Gholami, Z.; Amouzgar, P. Application of chitosan and its derivatives as adsorbents for dye removal from water and wastewater: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 113, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, R.; Arun, T.; Manickam, S.T.D. A review on applications of chitosan-based Schiff bases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 129, 615–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhi, R. Cross-Linked Hydrogel for Pharmaceutical Applications: A Review. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 7, 515–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xu, S.; Li, S.; Pan, H. Genipin-cross-linked hydrogels based on biomaterials for drug delivery: a review. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 9, 1583–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, B.; Luo, Y. Chitosan-based hydrogel beads: Preparations, modifications and applications in food and agriculture sectors–A review. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 152, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, M.; Mao, J.; Xu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, P. Photocrosslinkable chitosan hydrogels and their biomedical applications. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 2018, 57, 1862–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Yang, H.; Yang, J.; Peng, M.; Hu, J. Preparation and characterization of chitosan/gelatin/PVA hydrogel for wound dressings. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 146, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relucenti, M.; Familiari, G.; Donfrancesco, O.; Taurino, M.; Li, X.; Chen, R.; Artini, M.; Papa, R.; Selan, L. Microscopy Methods for Biofilm Imaging: Focus on SEM and VP-SEM Pros and Cons. Biology 2021, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, A. Biological applications of the scanning transmission electron microscope. J. Struct. Biol. 2022, 214, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocak, F.Z.; Yar, M.; Rehman, I.U. Hydroxyapatite-Integrated, Heparin- and Glycerol-Functionalized Chitosan-Based Injectable Hydrogels with Improved Mechanical and Proangiogenic Performance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beekes, M.; Lasch, P.; Naumann, D. Analytical applications of Fourier transform-infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy in microbiology and prion research. Veter- Microbiol. 2007, 123, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba kosz, M. Development of chitosan/gelatin-based hydrogels incorporated with albumin particles. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 14136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.S.; Ahmad, M.; Alqahtani, M.S.; Mahmood, A.; Barkat, K.; Khan, M.T.; Tulain, U.R.; Rashid, A. β-cyclodextrin chitosan-based hydrogels with tunable pH-responsive properties for controlled release of acyclovir: Design, characterization, safety, and pharmacokinetic evaluation. Drug Delivery 2021, 28, 1093–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Huang, Q.; Wei, K.; Xia, H. Quantitative analysis by thermogravimetry-mass spectrum analysis for reactions with evolved gases. Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVE 2018.

- Timur, M.; Pas a, A. Synthesis, characterization, swelling, and metal uptake studies of aryl cross-linked chitosan hydrogels. ACS omega 2018, 3, 17416–17424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczmarek-Szczepa ska, B.; Mazur, O.; Michalska-Sionkowska, M.; ukowicz, K.; Osyczka, A.M. The preparation and characterization of chitosan-based hydrogels cross-linked by glyoxal. Materials 2021, 14, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Cai, K.; Zhang, B.; Tang, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, W. Antibacterial polysaccharide-based hydrogel dressing containing plant essential oil for burn wound healing. Burn. Trauma 2021, 9, tkab041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieklarz, K.; Jenczyk, J.; Modrzejewska, Z.; Owczarz, P.; Jurga, S. An Investigation of the Sol-Gel Transition of Chitosan Lactate and Chitosan Chloride Solutions via Rheological and NMR Studies. Gels 2022, 8, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kud acik-Kramarczyk, S.; G b, M.; Drabczyk, A.; Kordyka, A.; Godzierz, M.; Wróbel, P.S.; Krzan, M.; Uthayakumar, M.; K dzierska, M.; Tyliszczak, B.e. Physicochemical characteristics of chitosan-based hydrogels containing albumin particles and aloe vera juice as transdermal systems functionalized in the viewpoint of potential biomedical applications. Materials 2021, 14, 5832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Ma, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhou, W.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Lin, J.; He, Q.; Leptihn, S.; Ouyang, H. Advanced hydrogels for the repair of cartilage defects and regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 6, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Dawson, C.; Lamb, M.; Mueller, E.; Stefanek, E.; Akbari, M.; Hoare, T. Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering: Addressing Key Design Needs Toward Clinical Translation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 849831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajabi, M.; McConnell, M.; Cabral, J.; Ali, M.A. Chitosan hydrogels in 3D printing for biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 260, 117768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, M.; Du, W.; Zhao, J.; Ling, G.; Zhang, P. Chitosan-based high-strength supramolecular hydrogels for 3D bioprinting. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 219, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.R.; Ribeiro, N.; Baptista-Silva, S.; Costa-Pinto, A.R.; Alves, N.; Oliveira, A.L. In situ Enabling Approaches for Tissue Regeneration: Current Challenges and New Developments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, G.; Sun, T.; Xiao, C. Injectable In Situ Forming Double-Network Hydrogel To Enhance Transplanted Cell Viability and Retention. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 5885–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicodemus, G.D.; Bryant, S.J. Cell Encapsulation in Biodegradable Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering Applications. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2008, 14, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Matysiak, S. Effect of pH on chitosan hydrogel polymer network structure. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 7373–7376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.-Y.; Ramezani, H.; Sun, M.; Xie, M.; Nie, J.; Lv, S.; Cai, J.; Fu, J.; He, Y. 3D printing of high-strength chitosan hydrogel scaffolds without any organic solvents. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 5020–5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Tan, Z.; Zeng, W.; Wang, X.; Shi, C.; Liu, Y.; He, H.; Chen, R.; Ye, X. Recent Advances of Chitosan-Based Injectable Hydrogels for Bone and Dental Tissue Regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 587658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, N.; Pradeep, A.; Jayakumar, R. Synthesis-structure relationship of chitosan based hydrogels. In Chitosan for Biomaterials III: Structure-Property Relationships; Springer: 2021; pp. 105-129.

- Li, P.; Fu, L.; Liao, Z.; Peng, Y.; Ning, C.; Gao, C.; Zhang, D.; Sui, X.; Lin, Y.; Liu, S.; et al. Chitosan hydrogel/3D-printed poly(ε-caprolactone) hybrid scaffold containing synovial mesenchymal stem cells for cartilage regeneration based on tetrahedral framework nucleic acid recruitment. Biomaterials 2021, 278, 121131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, B.; Feng, B.; Wang, H.; Yuan, H.; Xu, Z. Tetracycline hydrochloride loaded citric acid functionalized chitosan hydrogel for wound healing. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 19523–19530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, X.; Zhao, J.; Wang, S. Chitosan-based multifunctional hydrogel for sequential wound inflammation elimination, infection inhibition, and wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 235, 123847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Shao, H.; Li, X.; Ullah, M.W.; Luo, G.; Xu, Z.; Ma, L.; He, X.; Lei, Z.; Li, Q.; et al. Injectable immunomodulation-based porous chitosan microspheres/HPCH hydrogel composites as a controlled drug delivery system for osteochondral regeneration. Biomaterials 2022, 285, 121530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.K.; Dutta, S.D.; Hexiu, J.; Ganguly, K.; Lim, K.-T. 3D-printable chitosan/silk fibroin/cellulose nanoparticle scaffolds for bone regeneration via M2 macrophage polarization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 281, 119077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Wen, N.; Cao, J.-K.; Wang, H.-B.; Lü, S.-H.; Liu, T.; Lin, Q.-X.; Duan, C.-M.; Wang, C.-Y. The support of matrix accumulation and the promotion of sheep articular cartilage defects repair in vivo by chitosan hydrogels. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2010, 18, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumey, J.L.; Harrell, A.M.; Johnston, P.C.; Caliari, S.R. Serial Passaging Affects Stromal Cell Mechanosensitivity on Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels. Macromol. Biosci. 2023, e2300110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrader, J.; Gordon-Walker, T.T.; Aucott, R.L.; Van Deemter, M.; Quaas, A.; Walsh, S.; Benten, D.; Forbes, S.J.; Wells, R.G.; Iredale, J.P. Matrix stiffness modulates proliferation, chemotherapeutic response, and dormancy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology 2011, 53, 1192–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, F.-C.; Tsao, C.-T.; Lin, A.; Zhang, M.; Levengood, S.L.; Zhang, M. PEG-Chitosan Hydrogel with Tunable Stiffness for Study of Drug Response of Breast Cancer Cells. Polymers 2016, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batool, S.R.; Nazeer, M.A.; Yildiz, E.; Sahin, A.; Kizilel, S. Chitosan-anthracene hydrogels as controlled stiffening networks. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 185, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Fu, S.; Zhou, S.; Li, M.; Li, K.; Sun, W.; Zhai, Y. Advances in hydrogels based on dynamic covalent bonding and prospects for its biomedical application. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 139, 110024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-H.; Yu, C.-H.; Yeh, Y.-C. Engineering nanocomposite hydrogels using dynamic bonds. Acta Biomater. 2021, 130, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, S.; Gao, P.; Zhang, M.; Fan, C.; Lu, Q.; Li, C.; Chen, C.; Lin, B.; Jiang, Y. A tough chitosan-alginate porous hydrogel prepared by simple foaming method. J. Solid State Chem. 2021, 294, 121797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Wang, X.; Meng, T.; Yang, P.; Zhu, Z.; Min, H.; Chen, M.; Chen, W.; Zhou, X. Rapid one-step preparation of hierarchical porous carbon from chitosan-based hydrogel for high-rate supercapacitors: The effect of gelling agent concentration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 146, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasupalli, G.K.; Verma, D. Thermosensitive injectable hydrogel based on chitosan-polygalacturonic acid polyelectrolyte complexes for bone tissue engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 294, 119769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguanell, A.; del Pozo, M.L.; Pérez-Martín, C.; Pontes, G.; Bastida, A.; Fernández-Mayoralas, A.; García-Junceda, E.; Revuelta, J. Chitosan sulfate-lysozyme hybrid hydrogels as platforms with fine-tuned degradability and sustained inherent antibiotic and antioxidant activities. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 291, 119611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Lian, M.; Wu, Q.; Qiao, Z.; Sun, B.; Dai, K. Effect of Pore Size on Cell Behavior Using Melt Electrowritten Scaffolds. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 629270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matica, A.; Menghiu, G.a.; Ostafe, V. Biodegradability of chitosan based products. New Frontiers in Chemistry 2017, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Nicodemus, G.D.; Bryant, S.J. Cell Encapsulation in Biodegradable Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering Applications. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2008, 14, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Marra, K.G. Injectable, Biodegradable Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering Applications. Materials 2010, 3, 1746–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, I.; Arshad, M.; Yasin, T.; Ghauri, M.A.; Younus, M. Chitosan: A potential biopolymer for wound management. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 102, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, S.L.; Jackson, E.L.; Ferreira, A.M.; Hilkens, C.M.; Novakovic, K. In vitro evaluation of the biodegradability of chitosan–genipin hydrogels. Materials Advances 2022, 3, 7946–7959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasi ski, A.; Zieli ska-Pisklak, M.; Oledzka, E.; Sobczak, M. Smart hydrogels–synthetic stimuli-responsive antitumor drug release systems. International journal of nanomedicine 2020, 4541–4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.B.; Krolicka, M.; van den Broek, L.A.; Frissen, A.E.; Boeriu, C.G. Water-soluble chitosan derivatives and pH-responsive hydrogels by selective C-6 oxidation mediated by TEMPO-laccase redox system. Carbohydr Polym 2018, 186, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-P.; Weng, M.-C.; Huang, S.-L. Preparation and Characterization of pH Sensitive Chitosan/3-Glycidyloxypropyl Trimethoxysilane (GPTMS) Hydrogels by Sol-Gel Method. Polymers 2020, 12, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.M.; Simon, M.C. The tumor microenvironment. Current Biology 2020, 30, R921–R925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, M.-Z.; Jin, W.-L. The updated landscape of tumor microenvironment and drug repurposing. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdellatif, A.A.H.; Mohammed, A.M.; Saleem, I.; Alsharidah, M.; Al Rugaie, O.; Ahmed, F.; Osman, S.K. Smart Injectable Chitosan Hydrogels Loaded with 5-Fluorouracil for the Treatment of Breast Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.X.; Choi, S.Y.; Niu, X.; Kang, N.; Xue, H.; Killam, J.; Wang, Y. Lactic Acid and an Acidic Tumor Microenvironment suppress Anticancer Immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, B.; Cao, L.; Fang, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Liang, X.-J.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Y. Biomineralized hydrogel DC vaccine for cancer immunotherapy: A boosting strategy via improving immunogenicity and reversing immune-inhibitory microenvironment. Biomaterials 2022, 288, 121722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Jin, X.; Li, H.; Wei, C.-X.; Wu, C.-W. Onion-structure bionic hydrogel capsules based on chitosan for regulating doxorubicin release. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 209, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sponchioni, M.; Palmiero, U.C.; Moscatelli, D. Thermo-responsive polymers: Applications of smart materials in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 102, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedford, J.G.; Caminschi, I.; Wakim, L.M. Intranasal Delivery of a Chitosan-Hydrogel Vaccine Generates Nasal Tissue Resident Memory CD8+ T Cells That Are Protective against Influenza Virus Infection. Vaccines 2020, 8, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, Y.; Li, X.; Luo, Z.; Zheng, B.; Dong, S. Assembly Pattern of Supramolecular Hydrogel Induced by Lower Critical Solution Temperature Behavior of Low-Molecular-Weight Gelator. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 142, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Zheng, L.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, C.; Li, H. Light manipulation for fabrication of hydrogels and their biological applications. Acta Biomater. 2021, 137, 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Scheiger, J.M.; Levkin, P.A. Design and Applications of Photoresponsive Hydrogels. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1807333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Far, B.F.; Omrani, M.; Jamal, M.R.N.; Javanshir, S. Multi-responsive chitosan-based hydrogels for controlled release of vincristine. Commun. Chem. 2023, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, S.; Pandit, A.H.; Wang, L.-F.; Rattan, S. Strategy to design a smart photocleavable and pH sensitive chitosan based hydrogel through a novel crosslinker: a potential vehicle for controlled drug delivery. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 14694–14704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Li, H.; Ding, H.; Fan, Z.; Pi, P.; Cheng, J.; Wen, X. Allylated chitosan-poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) hydrogel based on a functionalized double network for controlled drug release. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 214, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, H.T.; Vu, T.T.; Karthika, V.; Jo, S.-H.; Jo, Y.-J.; Seo, J.-W.; Oh, C.-W.; Park, S.-H.; Lim, K.T. Dual cross-linked chitosan/alginate hydrogels prepared by Nb-Tz ‘click’ reaction for pH responsive drug delivery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 288, 119389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, W.-F.; Reddy, O.S.; Zhang, D.; Wu, H.; Wong, W.-T. Cross-linked chitosan/lysozyme hydrogels with inherent antibacterial activity and tuneable drug release properties for cutaneous drug administration. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2023, 24, 2167466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamaci, M.; Kaya, I. Chitosan based hybrid hydrogels for drug delivery: Preparation, biodegradation, thermal, and mechanical properties. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2022, 34, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Hua, S.; Tian, Y.; Liu, J. Chemical and physical chitosan hydrogels as prospective carriers for drug delivery: a review. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 10050–10064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanou, M.; Verhoef, J.; Junginger, H. Oral drug absorption enhancement by chitosan and its derivatives. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 52, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmar, K.; Bianco-Peled, H. Composite chitosan hydrogels for extended release of hydrophobic drugs. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 136, 570–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.K.; Moshikur, R.M.; Wakabayashi, R.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Kamiya, N.; Goto, M. Biocompatible Ionic Liquid Surfactant-Based Microemulsion as a Potential Carrier for Sparingly Soluble Drugs. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 6263–6272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Guan, Y.; Liu, P.; Gao, L.; Wang, Z.; Huang, S.; Peng, L.; Zhao, Z. Chitosan hydrogel, as a biological macromolecule-based drug delivery system for exosomes and microvesicles in regenerative medicine: a mini review. Cellulose 2022, 29, 1315–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M.Z.; Ratajczak, J. Extracellular microvesicles/exosomes: discovery, disbelief, acceptance, and the future? Leukemia 2020, 34, 3126–3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, P.; Luo, Y.; Ke, C.; Qiu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Hou, R.; Xu, L.; Wu, S. Chitosan-Based Functional Materials for Skin Wound Repair: Mechanisms and Applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 650598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, E.; Hou, W.; Liu, K.; Yang, H.; Wei, W.; Kang, H.; Dai, H. A multifunctional chitosan hydrogel dressing for liver hemostasis and infected wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 291, 119631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, H.; Lu, X.; Shahbazi, M.-A.; Wang, S. A triple-network carboxymethyl chitosan-based hydrogel for hemostasis of incompressible bleeding on wet wound surfaces. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 303, 120434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, R.; Zhang, X.; He, S.; Wen, J.; Zheng, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Preparation of pectin-chitosan hydrogels based on bioadhesive-design micelle to prompt bacterial infection wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 300, 120272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tan, B.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xie, X.; Liao, J. An injectable, self-healing carboxymethylated chitosan hydrogel with mild photothermal stimulation for wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 293, 119722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Yu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Y.; Xu, M.; An, P.; Zhou, Y.; Halila, S.; Wei, Y.; et al. Injectable chitosan/xyloglucan composite hydrogel with mechanical adaptivity and endogenous bioactivity for skin repair. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 313, 120904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Wu, L.; Yan, H.; Jiang, Z.; Li, S.; Li, W.; Bai, Y.; Wang, H.; Cheng, Z.; Kong, D.; et al. Microchannelled alkylated chitosan sponge to treat noncompressible hemorrhages and facilitate wound healing. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Su, B.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, C. Janus Self-Propelled Chitosan-Based Hydrogel Spheres for Rapid Bleeding Control. Adv. Sci. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, H.; Jia, W.; Li, M.; Chen, Z. New injectable chitosan-hyaluronic acid based hydrogels for hemostasis and wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 294, 119767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tengborn, L.; Blombäck, M.; Berntorp, E. Tranexamic acid – an old drug still going strong and making a revival. Thromb. Res. 2015, 135, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, J. Effects of degree of deacetylation on hemostatic performance of partially deacetylated chitin sponges. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 273, 118615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashakkorian, H.; Hasantabar, V.; Mostafazadeh, A.; Golpour, M. Transparent chitosan based nanobiocomposite hydrogel: Synthesis, thermophysical characterization, cell adhesion and viability assay. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 144, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Yan, C. Antimicrobial Properties of Chitosan and Chitosan Derivatives in the Treatment of Enteric Infections. Molecules 2021, 26, 7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, C.-L.; Deng, F.-S.; Chuang, C.-Y.; Lin, C.-H. Antimicrobial Actions and Applications of Chitosan. Polymers 2021, 13, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qing, X.; He, G.; Liu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Cai, W.; Fan, L.; Fardim, P. Preparation and properties of polyvinyl alcohol/N–succinyl chitosan/lincomycin composite antibacterial hydrogels for wound dressing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 261, 117875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, Y.; Kong, Q.; Tang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Mou, H.; Ying, R.; Li, C. Antimicrobial peptides/ciprofloxacin-loaded O-carboxymethyl chitosan/self-assembling peptides hydrogel dressing with sustained-release effect for enhanced anti-bacterial infection and wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 280, 119033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmingsen, L.M.; Giordani, B.; Pettersen, A.K.; Vitali, B.; Basnet, P.; Škalko-Basnet, N. Liposomes-in-chitosan hydrogel boosts potential of chlorhexidine in biofilm eradication in vitro. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 262, 117939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatvin, J.; Gao, J.; Locklin, J. Durable defense: robust and varied attachment of non-leaching poly“-onium” bactericidal coatings to reactive and inert surfaces. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 9433–9442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Wan, S.; Ren, X.; Chu, C.-C. Development of Inherently Antibacterial, Biodegradable, and Biologically Active Chitosan/Pseudo-Protein Hybrid Hydrogels as Biofunctional Wound Dressings. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 14688–14699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, M.; An, Y.; Wang, K.; Wu, Q.; Song, L.; Zhang, J.; He, H.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Freeze-Thawing Chitosan/Ions Hydrogel Coated Gauzes Releasing Multiple Metal Ions on Demand for Improved Infected Wound Healing. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2020, 10, e2001591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Zheng, Y.-W.; Liu, Q.; Liu, L.-P.; Luo, F.-L.; Zhou, H.-C.; Isoda, H.; Ohkohchi, N.; Li, Y.-M. Reactive oxygen species in skin repair, regeneration, aging, and inflammation. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) in living cells 2018, 8, 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.; Tan, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, Q.; Guo, Z. Water-soluble amino functionalized chitosan: Preparation, characterization, antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 217, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, M.-T.; Yang, J.-H.; Mau, J.-L. Antioxidant properties of chitosan from crab shells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 74, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Seidi, F.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Jin, Y.; Xiao, H. Injectable chitosan hydrogels tailored with antibacterial and antioxidant dual functions for regenerative wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 298, 120103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Huang, H.; Huang, C.; Liu, S.; Peng, X. pH-responsive magnolol nanocapsule-embedded magnolol-grafted-chitosan hydrochloride hydrogels for promoting wound healing. Carbohydr Polym 2022, 292, 119643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Huo, Q.; Lin, X.; Chu, X.; Deng, Z.; Guo, H.; Peng, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Drug-free contact lens based on quaternized chitosan and tannic acid for bacterial keratitis therapy and corneal repair. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 286, 119314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chi, J.; Jiang, Z.; Hu, H.; Yang, C.; Liu, W.; Han, B. A self-healing and injectable hydrogel based on water-soluble chitosan and hyaluronic acid for vitreous substitute. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 256, 117519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Deng, H.; Du, Y.; Shi, X. Electrodeposition induced covalent cross-linking of chitosan for electrofabrication of hydrogel contact lenses. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 292, 119678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ao, Y.; Zhang, E.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Wang, F. Advanced Hydrogels With Nanoparticle Inclusion for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Advanced biomaterials for osteochondral regeneration 2023, 32, 16648714. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, S.; Sun, S.; Liang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hu, H.; Luo, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, G. Highly tough and rapid self-healing dual-physical crosslinking poly(DMAA-co-AM) hydrogel. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 32988–32995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gong, X.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C. Construction of Carboxymethyl Chitosan Hydrogel with Multiple Cross-linking Networks for Electronic Devices at Low Temperature. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 9, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Yang, X.; Dong, X.; Cao, H.; Zhuang, S.; Gu, X. Easy regulation of chitosan-based hydrogel microstructure with citric acid as an efficient buffer. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 300, 120258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.C.; Zhang, H.; Ren, K.; Ying, Z.; Zhu, F.; Qian, J.; Ji, J.; Wu, Z.L.; Zheng, Q. Ultrathin κ-Carrageenan/Chitosan Hydrogel Films with High Toughness and Antiadhesion Property. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 9002–9009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, P.; Li, R.; Ye, S.; Shan, J.; Yuan, T.; Liang, J.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X. Lactobionic acid-modified chitosan thermosensitive hydrogels that lift lesions and promote repair in endoscopic submucosal dissection. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 263, 118001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Wu, J. Recent development in chitosan nanocomposites for surface-based biosensor applications. Electrophoresis 2019, 40, 2084–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facin, B.R.; Moret, B.; Baretta, D.; Belfiore, L.A.; Paulino, A.T. Immobilization and controlled release of β-galactosidase from chitosan-grafted hydrogels. Food Chem. 2015, 179, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Mohammadi, S.; Salimi, A. A 3D hydrogel based on chitosan and carbon dots for sensitive fluorescence detection of microRNA-21 in breast cancer cells. Talanta 2021, 224, 121895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmayssem, A.; Shalayel, I.; Marinesco, S.; Zebda, A. Investigation of GOx Stability in a Chitosan Matrix: Applications for Enzymatic Electrodes. Sensors 2023, 23, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.; Kim, U.; Mobed-Miremadi, M. Nanocomposite films as electrochemical sensors for detection of catalase activity. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 972008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, E.; Palomäki, T.; Ruuth, I.A.; Boeva, Z.A.; Nurminen, T.A.; Vänskä, R.T.; Zschaechner, L.K.; Pérez, A.G.; Hakala, T.A.; Wardale, M.; et al. Influence of enzyme immobilization and skin-sensor interface on non-invasive glucose determination from interstitial fluid obtained by magnetohydrodynamic extraction. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 206, 114123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.K.; Goddard, N.J.; Dixon, H.J.; Gupta, R. A Self-Referenced Diffraction-Based Optical Leaky Waveguide Biosensor Using Photofunctionalised Hydrogels. Biosensors 2020, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Qi, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, B.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, N. A surface-enhanced Raman scattering aptasensor for Escherichia coli detection based on high-performance 3D substrate and hot spot effect. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1221, 340141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Fang, C.; Ouyang, P.; Qing, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Du, J. Chaperone Copolymer Assisted G-Quadruplex-Based Signal Amplification Assay for Highly Sensitive Detection of VEGF. Biosensors 2022, 12, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, K.; Chelangat, W.; Druzhinin, S.I.; Karuri, N.W.; Müller, M.; Schönherr, H. Quantitative E. coli enzyme detection in reporter hydrogel-coated paper using a smartphone camera. Biosensors 2021, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Meng, Z.; Zhao, Z. A self-healing carboxymethyl chitosan/oxidized carboxymethyl cellulose hydrogel with fluorescent bioprobes for glucose detection. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 274, 118642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawski, F.d.M.; Dias, G.B.M.; Sousa, K.A.P.; Formiga, R.; Spiller, F.; Parize, A.L.; Báfica, A.; Jost, C.L. Chitosan/genipin modified electrode for voltammetric determination of interleukin-6 as a biomarker of sepsis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 224, 1450–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Sun, W.; Chen, R.; Yuan, Z.; Cheng, X. Fluorescent dialdehyde-BODIPY chitosan hydrogel and its highly sensing ability to Cu2+ ion. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 273, 118590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, M.M.S.; Schönherr, H. Enzyme-Sensing Chitosan Hydrogels. Langmuir 2014, 30, 7842–7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Ke, T.; Ling, Q.; Zhao, L.; Gu, H. Rapid self-healing and self-adhesive chitosan-based hydrogels by host-guest interaction and dynamic covalent bond as flexible sensor. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 273, 118533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, N.; Chen, K.; Liu, M.; Wang, F.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Xiao, X. Resilient and self-healing hyaluronic acid/chitosan hydrogel with ion conductivity, low water loss, and freeze-tolerance for flexible and wearable strain sensor. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Ren, X.; Bai, Y.; Liu, L.; Wu, G. Adhesive and tough hydrogels promoted by quaternary chitosan for strain sensor. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 254, 117298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Ren, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Huang, Q.; He, Y.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Yang, J.; Chen, Q.; et al. From design to applications of stimuli-responsive hydrogel strain sensors. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 3171–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CBH formation | Immobilized substances | detection target | detection parameter | low limit of detection | possible biomedical application | references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| membrane | bioprobes | VEGF | fluorescence signals | 23pM | diagnosis of early cancer and other diseases that involve angiogenesis | [138] |

| membrane | bioprobes | β-glucuronidase of E.coil | blue color | 100nM | diagnosis of E. coli infections | [139] |

| membrane | detection target | analytes that can interact with streptavidin | changes in the angle of light reflected by the film | 1.9 × 10−6 RIU | biomolecular detection | [136] |

| membrane | bioprobes | microRNA | fluorescence signals | 0.03fM | detection of microRNA-21 in MCF-7 cancer cells and multicolor imaging of the cells | [132] |

| membrane | bioprobes | Glucose | fluorescence signals | 0.029mM | glucose monitoring in vivo | [140] |

| surface layer | enzymes | Glucose | current change | 0.25mM | continuous glucose monitoring systems (CGMS) | [133] |

| surface layer | enzymes | hydrogen peroxide | current change | 0.07mM | detection of the catalase activity in biological samples | [134] |

| surface layer | bioprobes | E.coil | raman signal | 3.46 CFU/mL | hygiene | [137] |

| surface layer | antibodies | Interleukin-6 | current change | 0.03 pg/mL | detection of sepsis | [141] |

| surface layer | enzyme | Glucose | current change | 0.1 mM | monitoring glucose levels in diabetic patients without invasive blood sampling | [135] |

| 3D structure | bioprobes | Cu2+ | fluorescence signals | 4.75μM | screening infectious diseases, chronic disease treatment, health management, and well-being surveillance | [142] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).