Submitted:

04 May 2023

Posted:

05 May 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In vitro transcription on genomic DNA fragments

2.2. Cultivation of the E. coli knockout strains

2.3. Construction of primary transcript libraries

2.4. Sequencing and data processing

2.5. Sequence analysis

3. Results

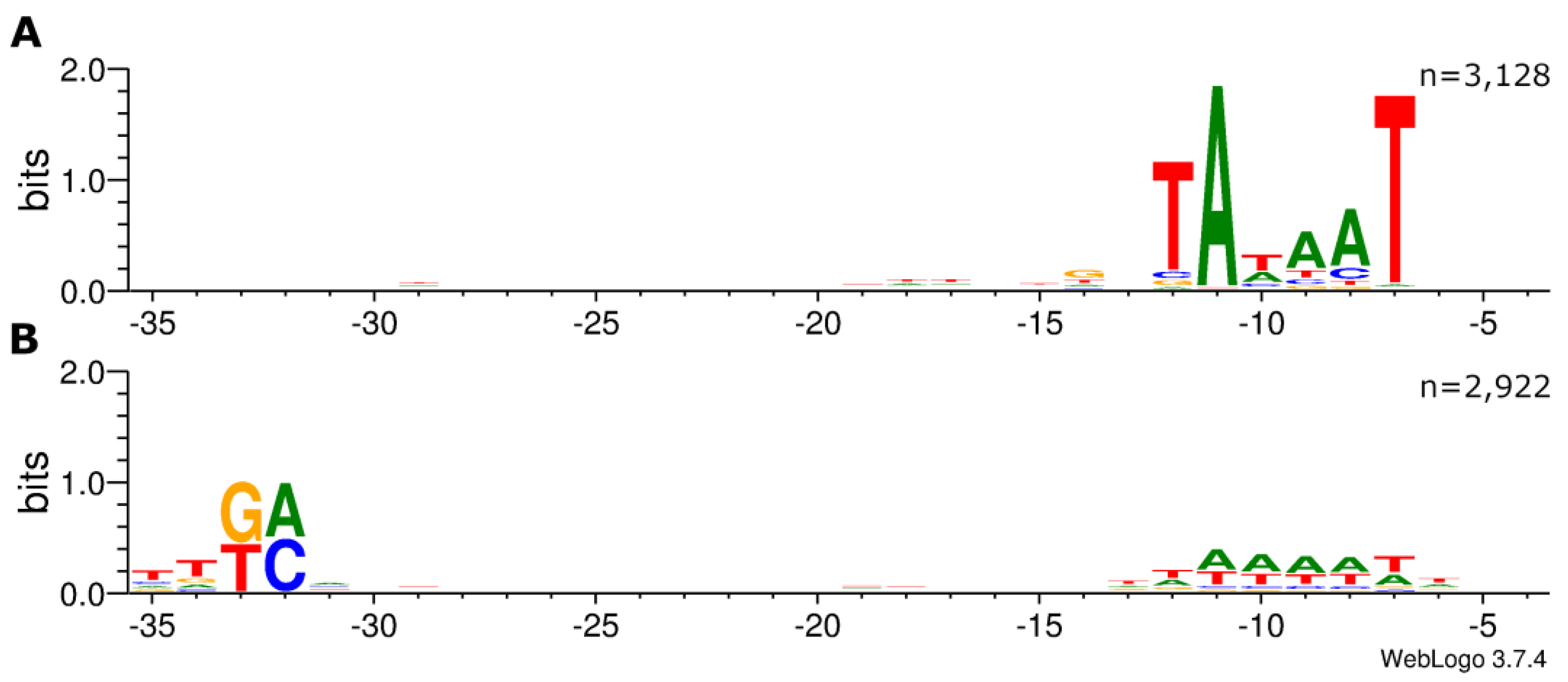

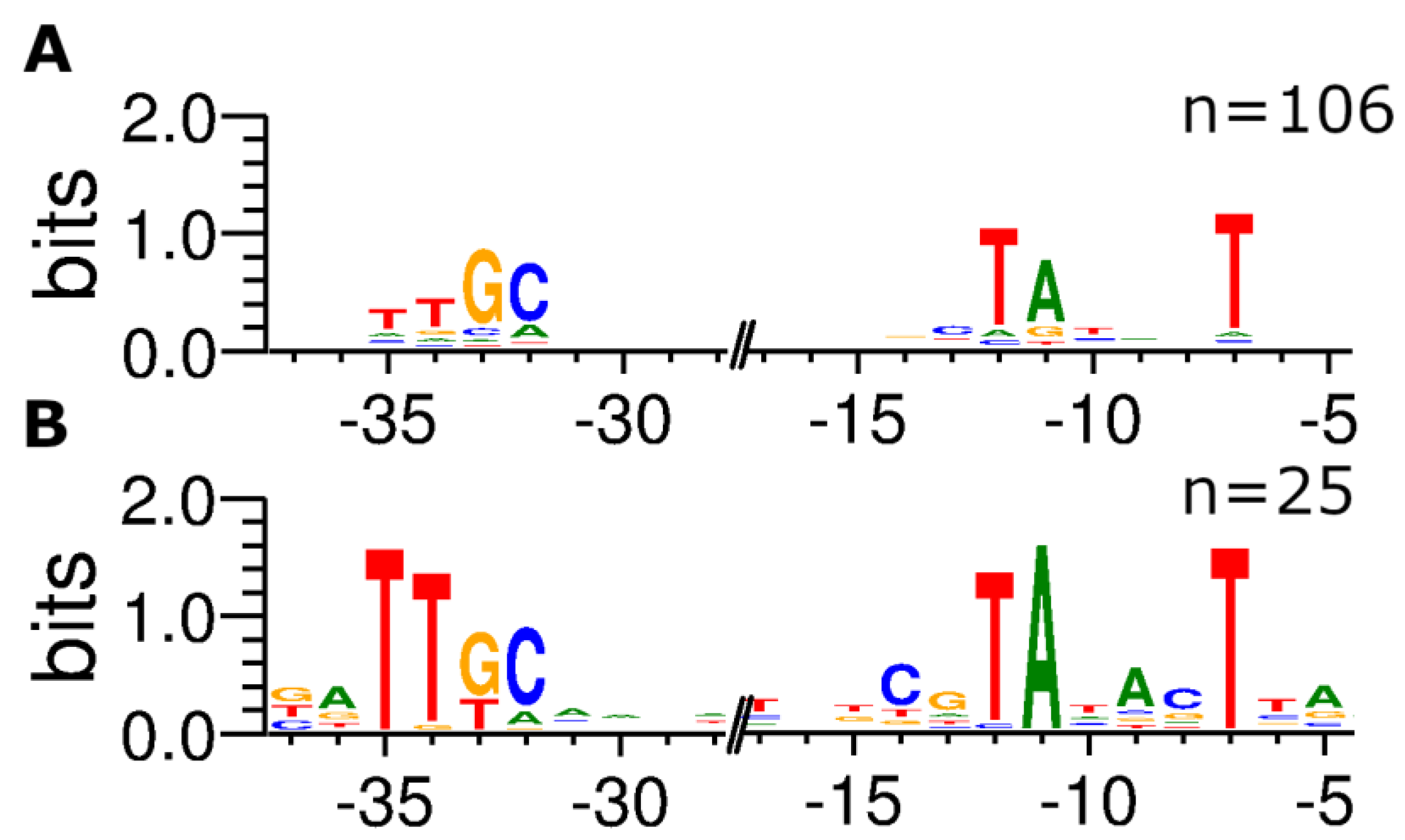

3.1. Development of ROSE and application to the analysis of σ70-dependent promoters in E. coli

3.2. Detailed Promoter Analysis by Comparison to Experimentally Characterized Promoters Listed in RegulonDB

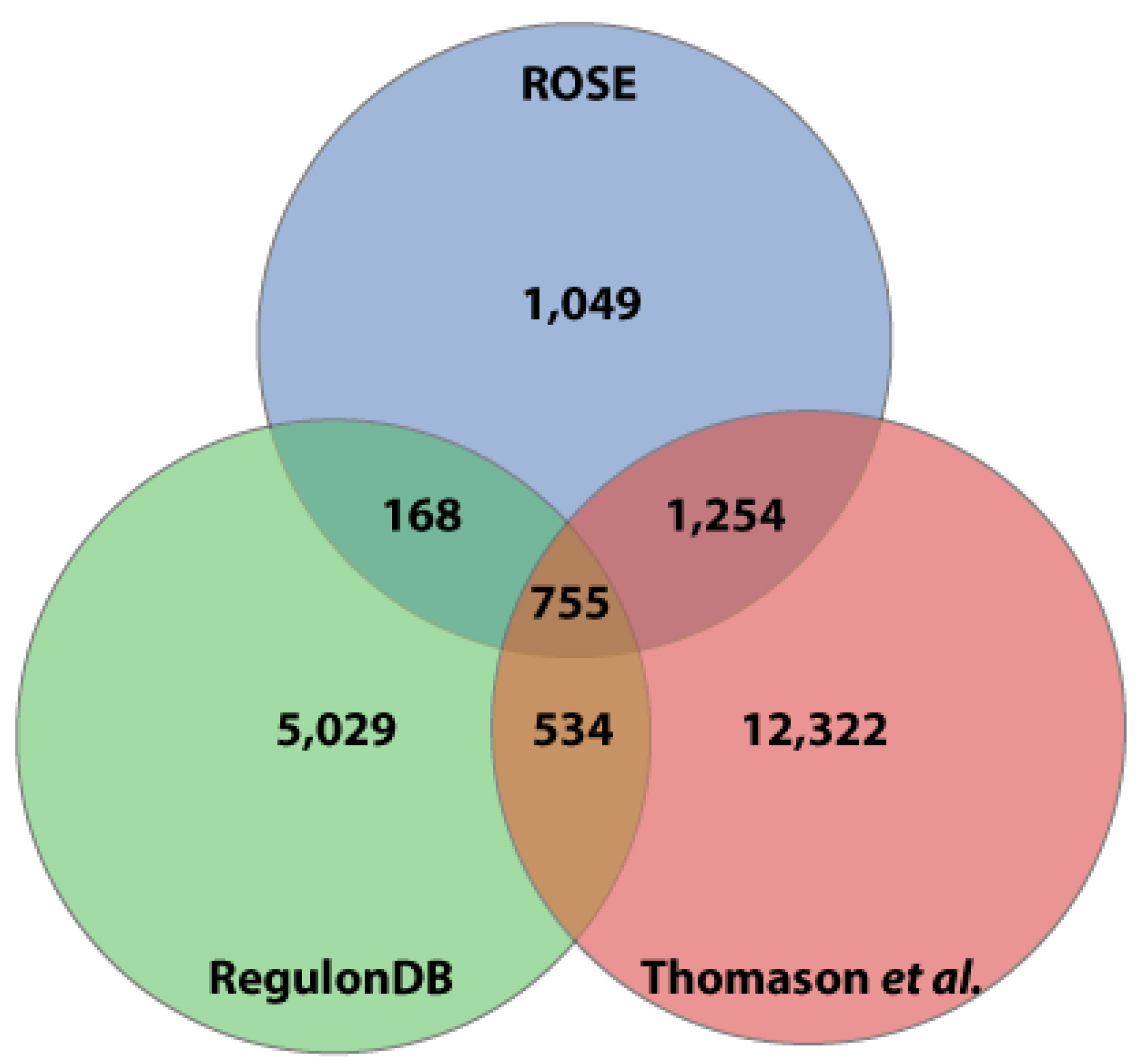

3.3. Comparison of the ROSE Data to Existing Comprehensive Genome-wide in vivo RNA-Seq Data Sets of E. coli K-12 MG1655

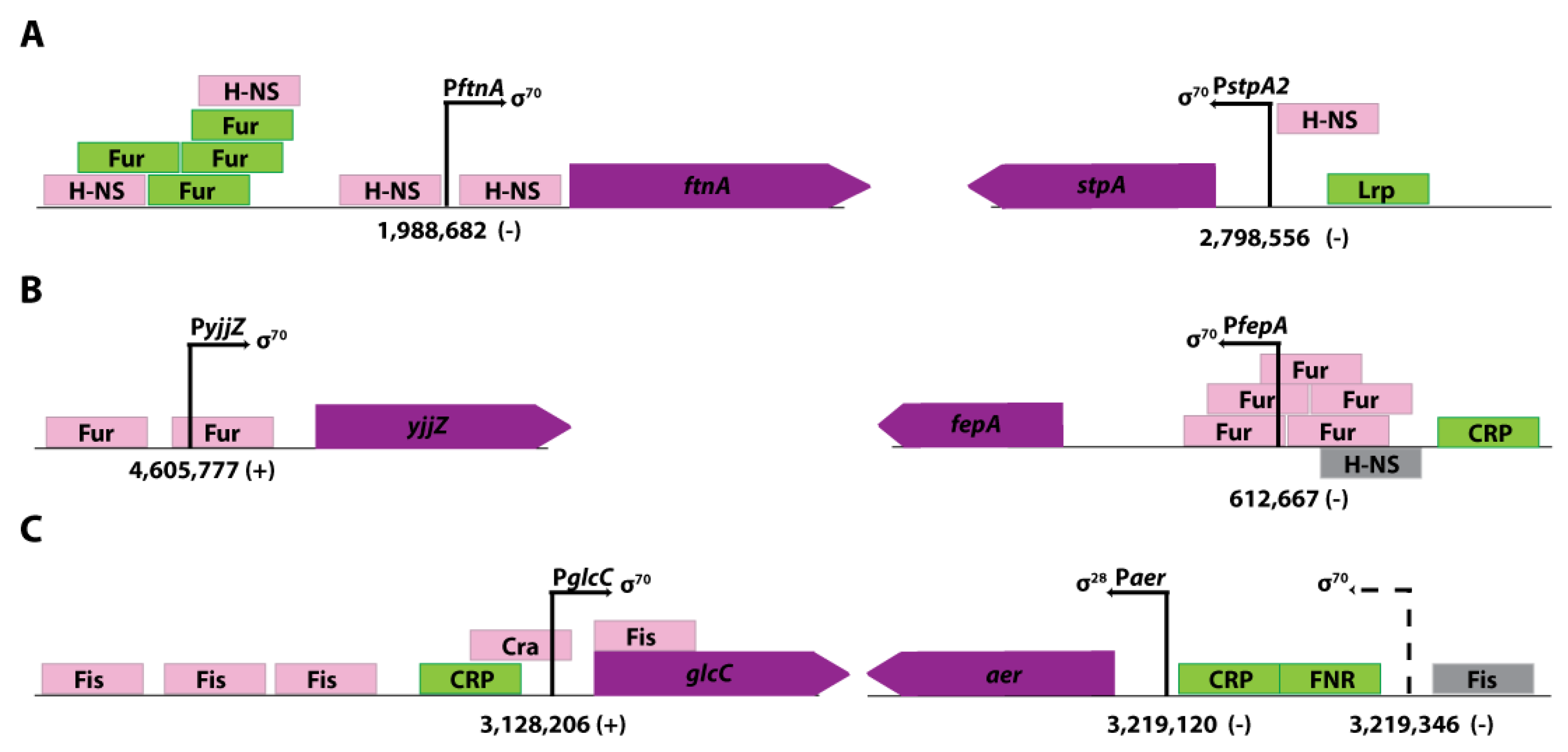

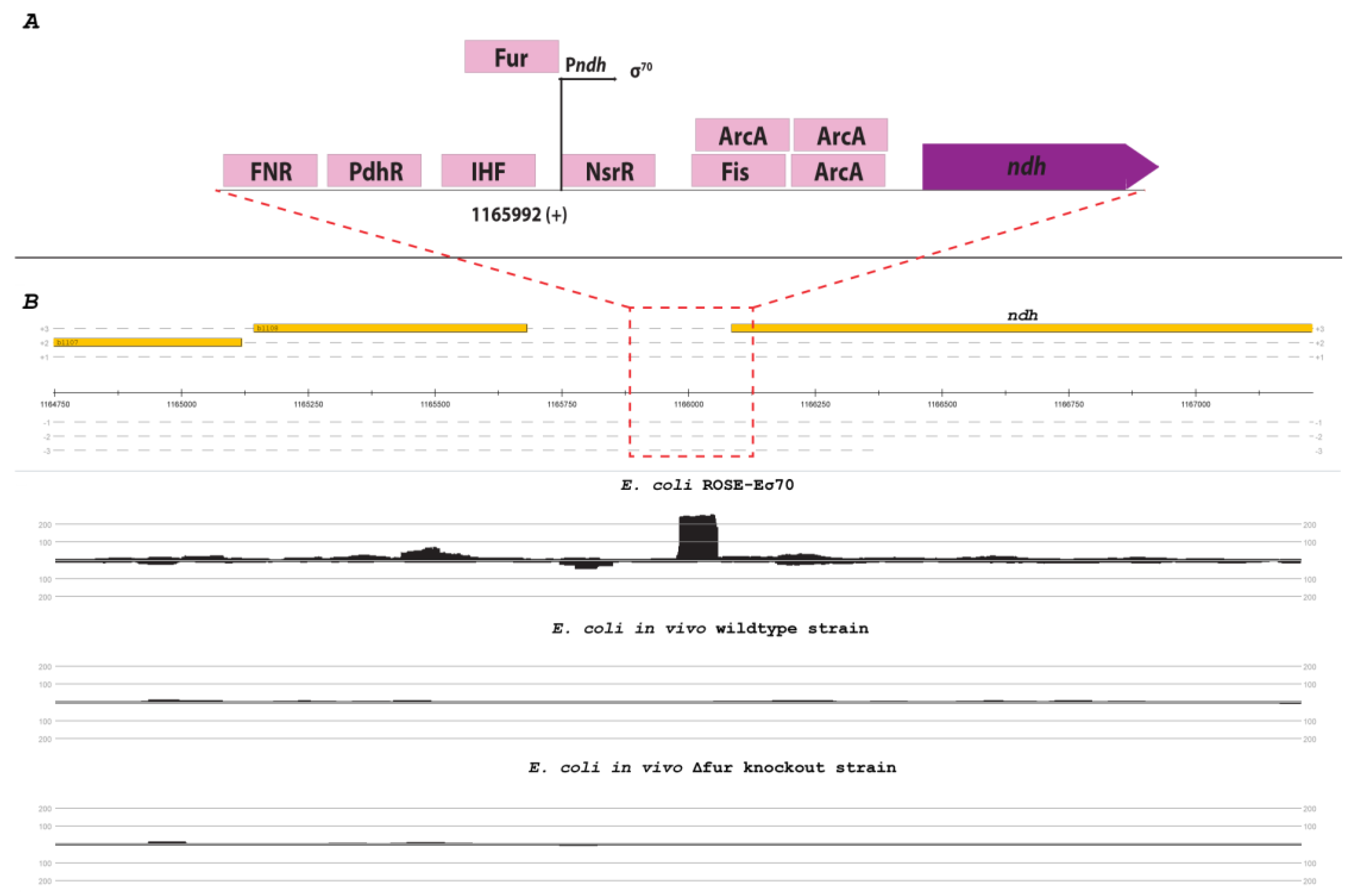

3.4. Transcription Start Sites of Promoters That are Repressed Under Standard in vivo Assay Conditions are Comprehensively Identified in ROSE Experiments

3.5. Promoters activated by transcriptional regulators in vivo are not identified in vitro

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Browning, D.F.; Busby, S.J. The regulation of bacterial transcription initiation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, D.F.; Busby, S.J.W. Local and global regulation of transcription initiation in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shultzaberger, R.K.; Chen, Z.; Lewis, K.A.; Schneider, T.D. Anatomy of Escherichia coli sigma70 promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 771–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maclellan, S.R.; Eiamphungporn, W.; Helmann, J.D. ROMA: an in vitro approach to defining target genes for transcription regulators. Methods 2009, 47, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciag, A.; Peano, C.; Pietrelli, A.; Egli, T.; Bellis, G. de; Landini, P. In vitro transcription profiling of the σS subunit of bacterial RNA polymerase: re-definition of the σS regulon and identification of σS-specific promoter sequence elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 5338–5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maclellan, S.R.; Wecke, T.; Helmann, J.D. A previously unidentified sigma factor and two accessory proteins regulate oxalate decarboxylase expression in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 69, 954–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeifer-Sancar, K.; Mentz, A.; Rückert, C.; Kalinowski, J. Comprehensive analysis of the Corynebacterium glutamicum transcriptome using an improved RNAseq technique. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busche, T. Analyse von Regulationsnetzwerken der Extracytoplasmic Function (ECF)-Sigmafaktoren in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Universität Bielefeld 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Otani, H.; Mouncey, N.J. RIViT-seq enables systematic identification of regulons of transcriptional machineries. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.R.; Sambrook, J. Molecular cloning : a laboratory manual., 4th ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilker, R.; Stadermann, K.B.; Doppmeier, D.; Kalinowski, J.; Stoye, J.; Straube, J.; Winnebald, J.; Goesmann, A. ReadXplorer--visualization and analysis of mapped sequences. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2247–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, W.; Gaudet, J.; Kent, W.J.; Muttumu, S.; Mango, S.E. Environmentally induced foregut remodeling by PHA-4/FoxA and DAF-12/NHR. Science 2004, 305, 1743–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Williams, N.; Misleh, C.; Li, W.W. MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W369–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, G.E.; Hon, G.; Chandonia, J.-M.; Brenner, S.E. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilker, R.; Stadermann, K.B.; Schwengers, O.; Anisiforov, E.; Jaenicke, S.; Weisshaar, B.; Zimmermann, T.; Goesmann, A. ReadXplorer 2-detailed read mapping analysis and visualization from one single source. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3702–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.M.; Hoffmann, S.; Darfeuille, F.; Reignier, J.; Findeiss, S.; Sittka, A.; Chabas, S.; Reiche, K.; Hackermüller, J.; Reinhardt, R.; et al. The primary transcriptome of the major human pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature 2010, 464, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Hong, J.S.-J.; Qiu, Y.; Nagarajan, H.; Seo, J.-H.; Cho, B.-K.; Tsai, S.-F.; Palsson, B.Ø. Comparative analysis of regulatory elements between Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae by genome-wide transcription start site profiling. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, M.K.; Bischler, T.; Eisenbart, S.K.; Förstner, K.U.; Zhang, A.; Herbig, A.; Nieselt, K.; Sharma, C.M.; Storz, G. Global transcriptional start site mapping using differential RNA sequencing reveals novel antisense RNAs in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, F.; Dam, P.; Chou, J.; Olman, V.; Xu, Y. DOOR: a database for prokaryotic operons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, D459–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Zavaleta, A.; Salgado, H.; Gama-Castro, S.; Sánchez-Pérez, M.; Gómez-Romero, L.; Ledezma-Tejeida, D.; García-Sotelo, J.S.; Alquicira-Hernández, K.; Muñiz-Rascado, L.J.; Peña-Loredo, P.; et al. RegulonDB v 10.5: tackling challenges to unify classic and high throughput knowledge of gene regulation in E. coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D212–D220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, A.M.; Collado-Vides, J. Sigma70 promoters in Escherichia coli: specific transcription in dense regions of overlapping promoter-like signals. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 333, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Typas, A.; Becker, G.; Hengge, R. The molecular basis of selective promoter activation by the sigmaS subunit of RNA polymerase. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 63, 1296–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.M.; Vogel, J. Differential RNA-seq: the approach behind and the biological insight gained. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014, 19, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, T.; Ara, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Takai, Y.; Okumura, Y.; Baba, M.; Datsenko, K.A.; Tomita, M.; Wanner, B.L.; Mori, H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006, 2, 2006–0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keseler, I.M.; Mackie, A.; Peralta-Gil, M.; Santos-Zavaleta, A.; Gama-Castro, S.; Bonavides-Martínez, C.; Fulcher, C.; Huerta, A.M.; Kothari, A.; Krummenacker, M.; et al. EcoCyc: fusing model organism databases with systems biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D605–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorman, C.J. H-NS: a universal regulator for a dynamic genome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommais, F.; Krin, E.; Laurent-Winter, C.; Soutourina, O.; Malpertuy, A.; Le Caer, J.P.; Danchin, A.; Bertin, P. Large-scale monitoring of pleiotropic regulation of gene expression by the prokaryotic nucleoid-associated protein, H-NS. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 40, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, A.; Dorman, C.J. The Escherichia coli stpA gene is transiently expressed during growth in rich medium and is induced in minimal medium and by stress conditions. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandal, A.; Huggins, C.C.O.; Woodhall, M.R.; McHugh, J.; Rodríguez-Quiñones, F.; Quail, M.A.; Guest, J.R.; Andrews, S.C. Induction of the ferritin gene (ftnA) of Escherichia coli by Fe(2+)-Fur is mediated by reversal of H-NS silencing and is RyhB independent. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 75, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagg, A.; Neilands, J.B. Ferric uptake regulation protein acts as a repressor, employing iron (II) as a cofactor to bind the operator of an iron transport operon in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 1987, 26, 5471–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, M.D.; Pettis, G.S.; McIntosh, M.A. Promoter and operator determinants for fur-mediated iron regulation in the bidirectional fepA-fes control region of the Escherichia coli enterobactin gene system. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176, 3944–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gosset, G.; Barabote, R.; Gonzalez, C.S.; Cuevas, W.A.; Saier, M.H. Functional interactions between the carbon and iron utilization regulators, Crp and Fur, in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, M.D.; Beach, M.B.; Koning, A.P.J. de; Pratt, T.S.; Osuna, R. Effects of Fis on Escherichia coli gene expression during different growth stages. Microbiology (Reading) 2007, 153, 2922–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Guest, J.R. Regulation of transcription at the ndh promoter of Escherichia coli by FNR and novel factors. Mol. Microbiol. 1994, 12, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Shimizu, K. Transcriptional regulation of main metabolic pathways of cyoA, cydB, fnr, and fur gene knockout Escherichia coli in C-limited and N-limited aerobic continuous cultures. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, J.D.; Bodenmiller, D.M.; Humphrys, M.S.; Spiro, S. NsrR targets in the Escherichia coli genome: new insights into DNA sequence requirements for binding and a role for NsrR in the regulation of motility. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 73, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niland, P.; Hühne, R.; Müller-Hill, B. How AraC interacts specifically with its target DNAs. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 264, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleif, R. Regulation of the L-arabinose operon of Escherichia coli. Trends Genet. 2000, 16, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, R.B.; Schleif, R.F. AraC-DNA looping: orientation and distance-dependent loop breaking by the cyclic AMP receptor protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1991, 218, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltzfus, L.; Wilcox, G. Effect of mutations in the cyclic AMP receptor protein-binding site on araBAD and araC expression. J. Bacteriol. 1989, 171, 1178–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Schleif, R. Catabolite gene activator protein mutations affecting activity of the araBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Marschall, C.; Muffler, A.; Fischer, D.; Hengge-Aronis, R. Role for the histone-like protein H-NS in growth phase-dependent and osmotic regulation of sigma S and many sigma S-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 3455–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschall, C.; Hengge-Aronis, R. Regulatory characteristics and promoter analysis of csiE, a stationary phase-inducible gene under the control of sigma S and the cAMP-CRP complex in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1995, 18, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, M.D.; Pittman, D.L. Methylating agents and DNA repair responses: Methylated bases and sources of strand breaks. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006, 19, 1580–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landini, P.; Busby, S.J. Expression of the Escherichia coli ada regulon in stationary phase: evidence for rpoS-dependent negative regulation of alkA transcription. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 6836–6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordes, P.; Conter, A.; Morales, V.; Bouvier, J.; Kolb, A.; Gutierrez, C. DNA supercoiling contributes to disconnect sigmaS accumulation from sigmaS-dependent transcription in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 48, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusano, S.; Ding, Q.; Fujita, N.; Ishihama, A. Promoter selectivity of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase E sigma 70 and E sigma 38 holoenzymes. Effect of DNA supercoiling. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 1998–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P. Transport of torsional stress in DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 14342–14347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzine, F.; Liu, J.; Sanford, S.; Chung, H.-J.; Levens, D. The dynamic response of upstream DNA to transcription-generated torsional stress. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004, 11, 1092–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, X.; Dages, S.; Dages, K.; Liu, Y.; Hua, Z.-C.; Makemson, J.; Leng, F. Transient and dynamic DNA supercoiling potently stimulates the leu-500 promoter in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 14566–14575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechold, U.; Potrykus, K.; Murphy, H.; Murakami, K.S.; Cashel, M. Differential regulation by ppGpp versus pppGpp in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 6175–6189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, M.M.; Gaal, T.; Josaitis, C.A.; Gourse, R.L. Mechanism of regulation of transcription initiation by ppGpp. I. Effects of ppGpp on transcription initiation in vivo and in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jishage, M.; Kvint, K.; Shingler, V.; Nyström, T. Regulation of sigma factor competition by the alarmone ppGpp. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 1260–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.L.; Hiremath, L.S.; Galloway, D.R. ToxR (RegA) activates Escherichia coli RNA polymerase to initiate transcription of Pseudomonas aeruginosa toxA. Gene 1995, 154, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pátek, M.; Muth, G.; Wohlleben, W. Function of Corynebacterium glutamicum promoters in Escherichia coli, Streptomyces lividans, and Bacillus subtilis. J. Biotechnol. 2003, 104, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M. Identification of new sigma K-dependent promoters using an in vitro transcription system derived from Bacillus subtilis. Gene 1999, 237, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Sagara, Y.; Aramaki, H. In vitro transcription system using reconstituted RNA polymerase (Esigma(70), Esigma(H), Esigma(E) and Esigma(S)) of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 183, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, J.-F.; Rodrigue, S.; Brzezinski, R.; Gaudreau, L. A recombinant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vitro transcription system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 255, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holátko, J.; Silar, R.; Rabatinová, A.; Sanderová, H.; Halada, P.; Nešvera, J.; Krásný, L.; Pátek, M. Construction of in vitro transcription system for Corynebacterium glutamicum and its use in the recognition of promoters of different classes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 96, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, T.; Wilhite, S.E.; Ledoux, P.; Evangelista, C.; Kim, I.F.; Tomashevsky, M.; Marshall, K.A.; Phillippy, K.H.; Sherman, P.M.; Holko, M.; et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets--update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D991–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).