1. Introduction

Endophthalmitis is considered an inflammation of the inner membranes of the eyeball resulting in the formation of an exudate in the vitreous cavity and/or anterior chamber. Endophthalmitis is caused by penetrating ocular trauma or an extension of corneal infection during eye surgery. Since endophthalmitis is a medical emergency, detailed investigation is ensured prior to the treatment process, particularly since the key component of treatment comprises the intravitreal injection of antibiotics. The patient’s expectations of a functional outcome could be slightly overestimated because elective surgery includes an implanted intraocular lens. However, a combination of various factors cannot guarantee anti-infectious safety despite ensuring all the necessary measures. This study describes a clinical case of step-by-step endophthalmitis treatment. The study highlights that endophthalmitis is a medical emergency, and the study has also describes intravitreal therapy based on antibiotic injection.

Endophthalmitis is a dreaded postoperative complication of cataract surgery, and its incidence and risk factors have been studied extensively [

1]. However, modern scientists distinguish five types of this disease: postoperative endophthalmitis, posttraumatic endophthalmitis, endogenous endophthalmitis, endophthalmitis associated with keratitis, and endophthalmitis associated with intravitreal injection [

2] Extensive research on the treatment and prevention of infectious postoperative endophthalmitis (IPOE) is being conducted worldwide.

An overview of the current practice patterns in nine European countries demonstrates that intracameral cefuroxime reduces the risk of IPOE following cataract surgery. It should be noted that the use of preoperative and intraoperative topical antibiotics and the use of intracameral or subconjunctival antibiotics vary significantly between and within countries [

3].

Acute postoperative endophthalmitis is a formidable surgical complication resulting in loss of visual function, and subsequent anatomical loss of the eye without adequate treatment [

4]. It should be noted that acute bacterial postoperative endophthalmitis may occur following abdominal surgery on the eyeball. The following are known cases of surgery with the corresponding likelihood of endophthalmitis. Known surgeries associated with cases of endophthalmitis are cataract surgery (0.039–0.59%) [

5], glaucoma surgery (0.17–13.2%) [

6], vitreoretinal surgery (up to 1.3%) [

7], intravitreal injections(0.02–0.32%) [

8], etc. Thus, any sterling performance operation does not preclude the risk of endophthalmitis development.

Endophthalmitis is usually clinically diagnosed and confirmed by cultures of the vitreous and/or aqueous (or blood cultures in endogenous cases) [

9]. Endophthalmitis is usually promptly diagnosed and treated in cases that occur soon following eye surgery, intravitreal injections, or eye trauma. However, there could be delays in the diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis, particularly when outpatients present to the ophthalmologist with eye symptoms but without systemic symptoms or known risk factors. This study describes a clinical case of step-by-step endophthalmitis treatment. The study highlights that endophthalmitis is a medical emergency; the study has also describes intravitreal therapy based on antibiotic injection.

2. Case Presentation

An 82-year-old patient visited our institution on 7th October 2020. Vis left = 0.35, intraocular pressure (IOP) = 13. No somatic pathology was identified with the exception of surgical treatment for sinusitis in 2015. The preoperative laboratory findings were comprehensively surveyed. Classical phacoemulsification using the Centurion cataract (Alcon) through access 2.0 using soft-shell technology on the left eye under stationary conditions was attempted.

In 2015, cataract surgery was performed in the right eye. The operation was performed without complications, and an intraocular lens (IOL) MA60AC (Alcon) was implanted. The BCVA on the right at the time of inspection was 20/20 and the IOP = 11.

The rupture of the posterior capsule with dislocation of the lens fragments into the vitreous cavity had occurred during surgery on 8th October 2020 at 9.05 AM. The accident was caused by the topical fluctuation of the posterior capsule during occlusion of the phaco probe. The transfer of the patient to a vitreoretinal surgeon was ensured promptly. The surgeon administered povidone-iodine with a pause of 3 min, following which he washed it off and performed a sutureless 25 Ga subtotal 3-port vitreolensectomy and implantation of the MA60AC IOL with infringement in the anterior capsulorhexis. The dislocated fragments were most likely soft; therefore, fragmentation of the lens masses was not considered necessary.

The second surgeon used a balanced salt solution (BSS), injected 1 mg of cefuroxime into the anterior chamber subconjunctivally. Dexazone was administered intravenously by an anesthesiologist. Disposable consumables were used in the above-mentioned interventions. The surgery was completed without the use of plugging agents (BSS in the vitreal cavity), cefuroxime 1 mg introduced into the anterior chamber. All surgical approaches were sutured (8-0 vicryl on the sclerotomy, 10-0 nylon on the cornea). All consumables are disposable.

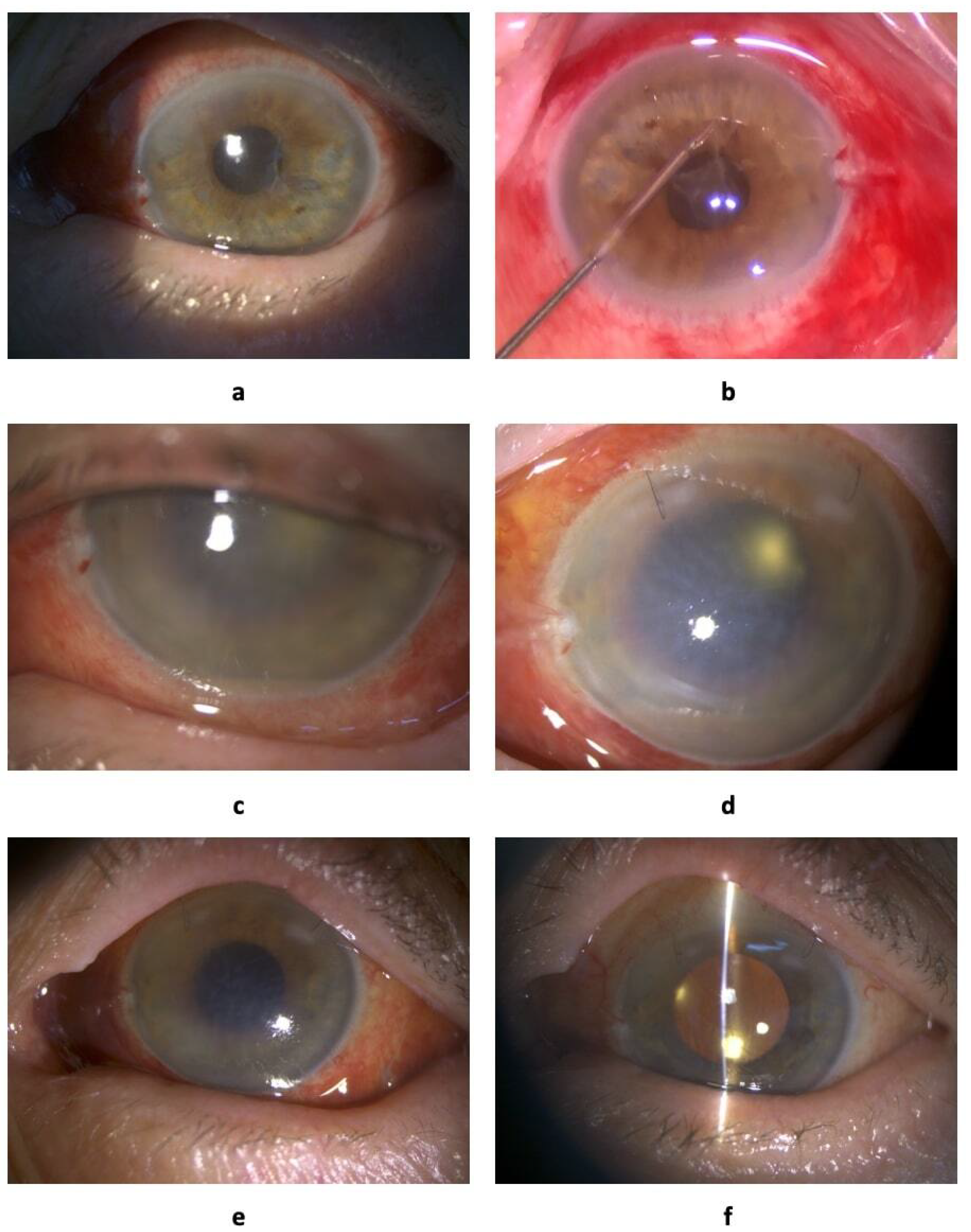

The patient complained of decreased visual acuity and pain in the operated eye on 9th October 2020 at 10.00 AM. Vis = 0.005, IOP = 14, transparent cornea, and fibrin filaments in the anterior chamber and on the IOL showed weak fundus reflex

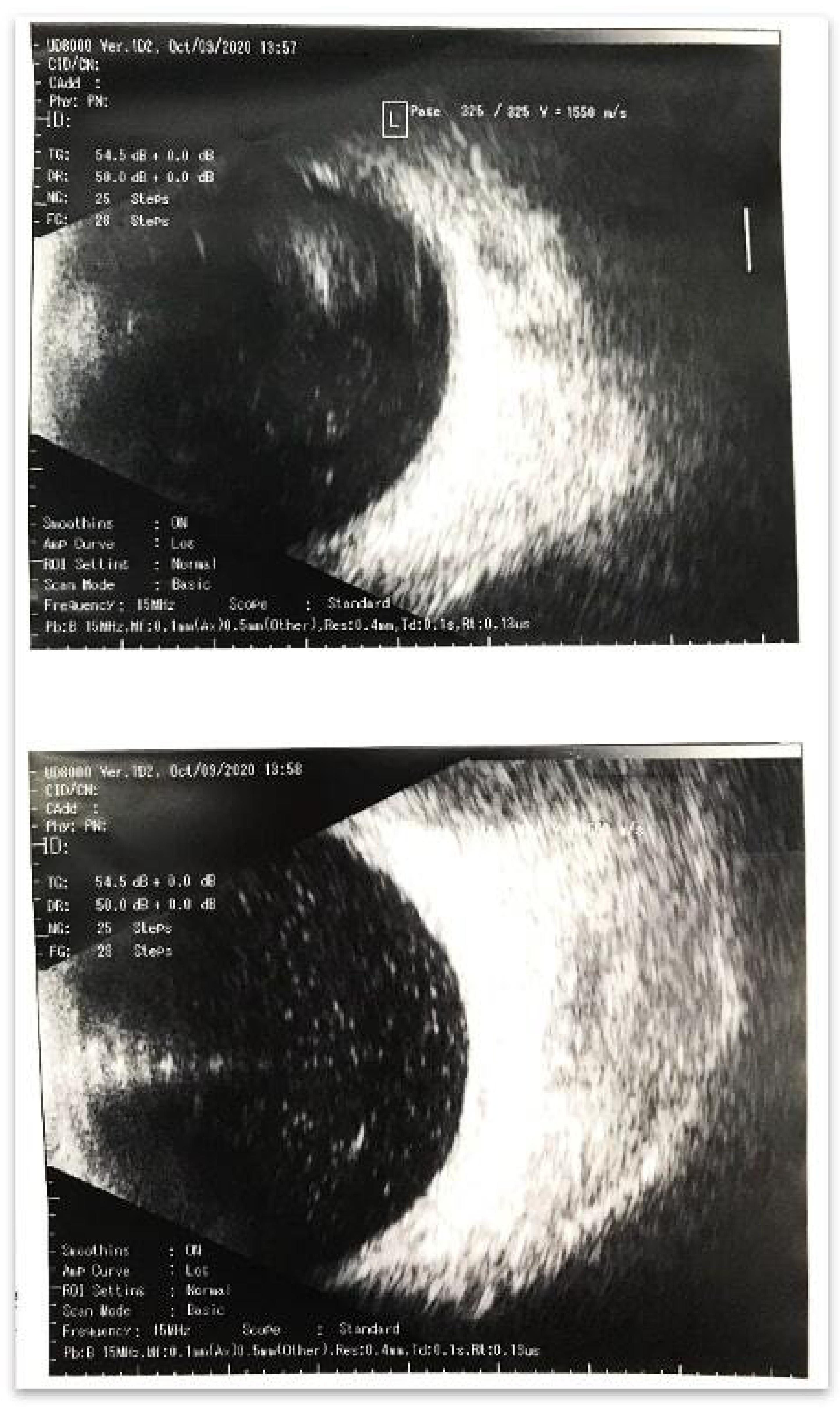

Figure 1a. The ultrasonography conducted at 10.30 AM revealed a massive hyperreflexive inflammatory suspension in the vitreous cavity (

Figure 2). It should be noted that clinical manifestations appeared, such onset which is not typical for endophthalmitis, especially in the avitreal eye were observed. Endophthalmitis usually occurs within 3–7 days or more. Our findings could indicate a massive drift of the pathogen or an autoimmune reaction. In this case, the absence of hypotension may indirectly indicate tightness of access.

The patient underwent total 3-port 25 Ga vitrectomy, washing of the anterior chamber with removal of exudative membranes under the protection of viscoelastics (

Figure 1b); culture was obtained from the anterior chamber and vitreous cavity to identify the pathogen and determine the sensitivity to antibiotics on 9th October 2020 at 2.30 PM (4.5 hours after the development of the first clinical symptoms). At the final stage of the operation, 1 mg / 0.1 ml of vancomycin and 2.25 mg / 0.1 ml of ceftazidime were injected into the vitreous cavity. The following conservative treatment was established: drops, levofloxacin, dexamethasone, atropine 1%; subconjunctival administration, mezaton, ceftazidime, and vancomycin; and intravenous administration, dexamethasone. The above protocol should be considered when establishing guidelines for the same. During the initial examination, the autoimmune nature of the process may could be considered; however, during the intraoperative process, classic infectious condition was evident. The tightly welded exudative membrane in the anterior chamber, diffuse suspension in the vitreous cavity, leukocyte muffs along the vascular arcades, and diffuse intraretinal hemorrhages support this assertion. All these factors clearly indicated infectious hemorrhagic retinovasculitis. Blue staining of the accesses before the operation demonstrated complete absence of filtration. All corneal and scleral accesses were sutured at the end of the surgery.

The patient presented with a sharp increase in pain in the eyeball and complete absence of visual function on 10th October 2020 09:15 AM. Vis = pr.l. incertae, IOP = 8. Photographs could not be taken owing to blepharospasm.Swollen cornea, loose, descemetitis, 2 mm hypopyon, and no fundus reflex were observed. The ultrasonography revealed a diffuse hyperreflective suspension in the vitreous cavity at 02:00 PM. The patient underwent repeated washing of the anterior chamber and vitreous cavity in the operating room on 10th October 2020 at 02:30 PM. At the final stage of the operation, 1 mg / 0.1 ml vancomycin 2.25, and 1 mg / 0.1 ml ceftazidime were administrated into the vitreous cavity. Soft contact lens use should have been confirmed. Conservative treatment was continued. It should be emphasized that we have repeatedly encountered cases of an imaginary deterioration of the clinical picture on the first day following surgery for endophthalmitis due to surgical trauma, the administration of antibiotics, and the possible production of exotoxins from dead microorganisms. Owing to the clinical background of the above-mentioned perioperative consequences, critical concerns were not raised. However, massive exudation in the vitreous cavity is not specific to endophthalmitis, which raises concerns regarding the complexity of the clinical case. Thus, to minimize the risk of erosion owing to the repeated washing of the vitreous cavity, a soft contact lens is recommended. It should be noted that the peculiarities of evacuation of intravitreal antibiotics in avitreal pseudophakic eyes (about 9 hours) [

10] justify their more frequent intravitreal administration (daily). Maintaining the required concentration of antibiotic in the vitreal cavity is especially important in infections with mild or moderate antibiotic sensitivity (as expected in this clinical case). Our own clinical experience has repeatedly proven this.

No positive dynamics on 11th October 2020 at 9:45 AM. Vis = pr.l. incertae, IOP = 8. Edematous cornea, descemetitis, hypopyon of 2 mm, and absence of the fundus reflex (

Figure 1c) were observed. Based on the ultrasonography at 1:00 PM, diffuse hyperreflective suspension in the vitreous cavity was defined. The patient underwent intravitreal administration of 1 mg / 0.1 ml of vancomycin and 2.25 mg / 0.1 of ceftazidime. Conservative treatment was continued. Repeated laboratory blood tests demonstrated stable arecativity of all indicators. Therefore, resistant microflora or other infectious agents could be considered in this case. Nevertheless, treatment based on maintaining the concentration of antibiotics in the vitreous cavity was continued since the antibiotic demonstrated rapid evacuation in the avitreal eye. Significant positive dynamics in ultrasonography were observed on 12th October 2020 at 9:00 AM. Vis = pr.l. incertae, IOP = 8. Photographs were not taken. Edematous cornea, descemetitis, hypopyon of 1 mm, and no fundus reflex were observed The ultrasonography at 9:10 AM revealed a moderate hyperreflective suspension in the vitreous cavity. The patient underwent intravitreal administration of 1 mg / 0.1 ml of vancomycin and 2.25 mg / 0.1 ml of ceftazidime at 11:00 AM. Conservative treatment was continued as per the same regimen except for intravenous injections of dexamethasone.

The results of the bacteriological culture with an analysis of sensitivity to antibiotics were obtained at 1:00 PM (for 4 days). Inoculation from the vitreous cavity and anterior chamber revealed abundant growth of Candida albicans sensitive to amphotericin-B. Hence, antifungal drug therapy was not considered since the antibiotic treatment had been initiated 2 hours prior. Intravitreally administrated antibiotics (mentioned above) could be considered based on the positive dynamics in the patient’s condition according to the ultrasonography findings on 12th October 2020 at 9:00 AM. The results of the bacteriological culture have raised questions, since postoperative candidal endophthalmitis does not develop the subsequent day following the intervention, does not present such an aggressive course, and the likelihood of intraoperative drift is casuistry.

There was a lack of positive dynamics on 13th October 2020 at 9:15 AM. Vis = pr.l. incertae, IOP = 11. Edematous cornea, descemetitis, hypopyon of 1 mm (not visible in the photograph), and absence of fundus reflex (

Figure 1d) were observed. The ultrasonography at 10:00 AM revealed a moderate hyperreflective suspension in the vitreous cavity. The patient underwent intravitreal administration of 10

g / 0.1 ml of amphotericin-B. Subconjunctival antibiotic injections were eliminated from the conservative therapy regimen. Ultrasonography results worsened since the antibiotics were injected intravitreally four times. Amphotericin was administered despite complete denial of the fungal etiology of the process. Antibiotics were eliminated from the conservative therapy regimen. Positive dynamics observed on 14th October 2020 at 9:10 AM. Vis = pr.l. incertae, IOP = 8. The cornea was moderately edematous with mild descemetitis, no hypopyon, and no fundus reflex (

Figure 1e). The ultrasonography at 10:00 AM revealed a moderate hyperreflective suspension in the vitreous cavity. Conservative treatment with levofloxacin, dexamethasone, and atropine (1% drops) was initiated. Apparently, amphotericin was considered a factor in the improvement; however, while the anterior chamber improved, the posterior chamber worsened. Nevertheless, intravitreal therapy was stopped and treatment with drops was initiated. For several days, the anterior chamber was not photographed.

Weak positive dynamics were observed on 15th October 2020 at 10:00 AM. Vis = pr.l. incertae, IOP = 9. The cornea was slightly edematous, with local descemetitis, no hypopyon, and a weak reflex of the fundus were observed. The ultrasonographyat 10:10 AM revealed no practical damage to the vitreous cavity. Conservative treatment was continued as before.

Positive dynamics were observed on 16th October 2020 at 09:00 AM. Vis = pr.l. incertae, IOP = 9. The cornea was edematous in the upper part, and local descemet, no hypopyon, and slightly pink fundus were observed. The ultrasonography at 9:15 AM revealed a clear vitreous cavity. Conservative treatment was continued same as before.

Positive dynamics and reappearance of vision appeared were observed on 17th October 2020 at 10:00 AM. Vis = 0.005, IOP = 7. Local descemetitis, no hypopyon, and pink fundus reflex were observed The ultrasonography at 10:00 AM revealed that the vitreous cavity was clean. Conservative treatment was continued same as before.

Positive dynamics were observed on 18th October 2020 at 11:00 AM. Vis = 0.005, IOP = 9. The cornea was transparent, and there was no hypopyon, while the fundus was pink. The ultrasonography at 9:40 AM revealed that the vitreous cavity was clean. Conservative treatment was continued in the same manner. Weak positive dynamics were observed on 19th October 2020 at 9:00 AM. Vis = 0.005, IOP = 8. Transparent cornea, no hypopyon, and pink fundus reflex (

Figure 1 f) were observed. The ultrasonography at 9:15 AM revealed local hyperreflective suspension in the vitreous cavity. The patient was discharged from the hospital; conservative drops treatment at home was prescribed: levofloxacin was administered 5 times a day, dexamethasone 8 times a day, and atropine 3 times a day. Resurvey was recommended after 2 weeks. Following a single administration of amphotericin, the patient used drops for 4 days. As a result, we observed weak but positive dynamics. On the day of discharge from the hospital, a local hyperreflective suspension was detected in the vitreous cavity; however, it was considered a synchisis of the remains of the vitreous body.

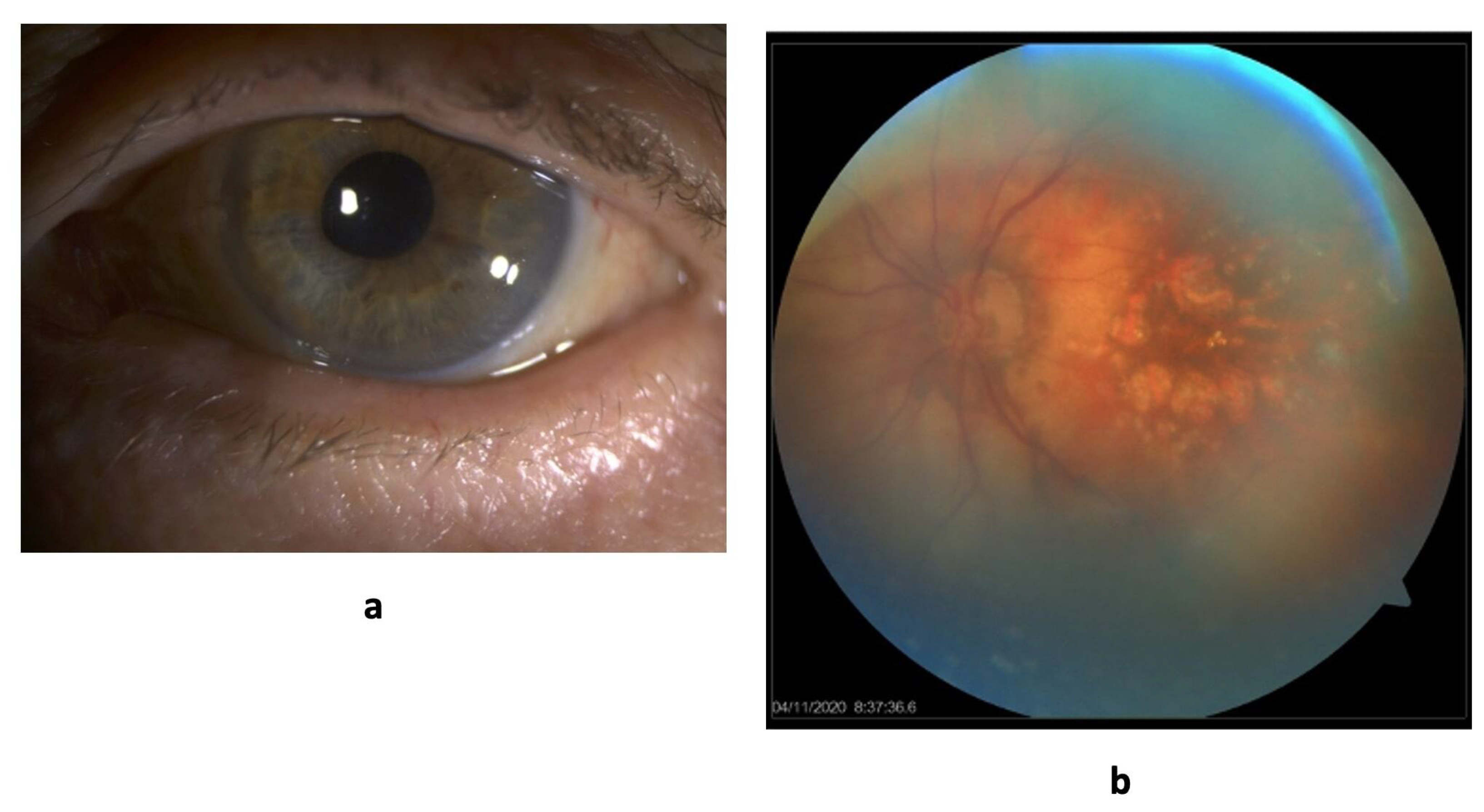

The last examination of the patient took place on February 15, 2022. Visual acuity is 0.1. Optical media are transparent. The optic disc is partially decolorized, there is a narrowing of the visual fields by 10 degrees from the temporal side.

4. Discussion

Despite the efforts of the analysis of the clinical case, repeated visits indicated secondary partial atrophy of the optic nerve and retinal structures. It should be mentioned that the treatment by trial and error permitted obtaining an anatomical result; however, the functional result remained relatively low. The pathology behind this process is questionable.The pathogenesis potentially could involve putative yeast fungi; however, fungi do not possess the ability of neurotoxicity and retinotoxicity, especially in a short time period of time. In fact, certain bacterial agents are capable of producing exotoxins and endotoxins, especially when they are extensively neutralized by antibiotics. On the contrary, the pathogenesis could be related to the toxic effects of therapeutic agents, whether antibiotic or antimycotic, the toxicity cannot be firmly ascertained. Therefore, a combination of these factors at play is more accurate. However, clinicians sometimes are forced to sacrifice function for the sake of anatomy in the treatment of such cases.

Clinicians should be cautious regarding guaranteed anti-infectious protection unavailability in the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative periods. Differential diagnostics based on the clinical picture and laboratory data remain challenging owing to the absence of effective means over pathogens. Bacterial endophthalmitis is a bacterial infection resulting inconsequent inflammation of the posterior segment of the eye, although the anterior chamber may also be adversely affected [

11]. Permanent eye damage and loss of vision may result in bacterial endophthalmitis. In particular, they could be of exogenous or endogenous origins. Intravitreal administration of antibiotics is an effective means of treating bacterial endophthalmitis. Drug administration permits achieving therapeutic concentrations in the posterior chamber. However, drug administrations are a source of inherent risks such as toxicity effects [

12] retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, and cataract [

12]. In this case, we demonstrated the daily conservative and surgical activity of medical personnel aimed at the anatomical safety of the eye. We do not associate the frequency of intravitreal administration of antibiotics with the risks of toxic damage, since this is proven by our clinical experience and scientific research. In this clinical case, a collision with a mixed flora or a highly virulent bacterial flora that is poorly sensitive to antibiotics is highly likely. We do not have sufficient confidence in the plausibility of the fungal etiology of the process.

5. Learning Points

A single vitreoretinal intervention (lavage of the vitreal cavity with the introduction of antibiotics) does not continually stop the pathological process in avitreal and pseudophakic eyes. It should be note that microbial agents have different sensitivity to antibiotics (dose-dependent and time-dependent effects), and antibiotics half-life is approximately high.

Removal of the pathological substrate from the vitreal cavity is a necessary and highly effective procedure, especially in cases of repeated massive exudation.

The results of routine laboratory studies may perform conflicting results, so the correlation of data with the clinical picture, and treatment response is extremely important. Particularly, with a possible mixed infection.

Regression of clinical symptoms may be very slow because of low microbe sensitivity to the antibiotic. To date, highly resistant microflora is not uncommon issue, and the recovery period may last several years.

The aim of endophthalmitis treatment is the anatomical preservation of the eyeball. Thus, the reason of low functional results is complex of pathological reactions (toxins of microbial agents, frequency of interventions, concomitant ophthalmic pathology).