The self has been a topic of interest at least since human animals became aware of their own self, arguably over 60,000 years ago (Leary, 2004). There is no universally accepted definition of the self, but a general agreement is that it is “… multidimentional in nature, made up of both conscious and unconscious layers, and is informed by observations of others” (Carden et al., 2022, p. 143). Here, the self is understood as all conceivable private and public aspects making up who a person is, including thoughts, emotions, goals, values, sensations, memories, traits, attitudes, physical attributes, behaviors, and skills (Morin, 2006, Figure 2). The main cognitive process that makes it possible for the self to apprehend itself and form an idea of itself (a self-concept) is self-reflection: The mental act of examining our self while being motivated by a healthy curiosity or interest in who we are (Trapnell & Campbell, 1999). There are many unknowns regarding the self, but a few solid empirical facts are emerging in the literature. One is that self-reflection and its negative counterpart, self-rumination, as well as several key self-processes such as self-regulation, self-esteem, and self-knowledge, most likely rely on inner speech (Morin, 2005; 2018; in press)—a verbal conversation we engage in with ourselves about ourselves. Another accepted view is that self-processes are interrelated in very complex ways (Mograbi et al., 2021; Morin & Racy, 2021), so that if one mechanism is compromised (e.g., thinking about one’s past), others will also suffer (e.g., thinking about one’s future) (Schacter et al., 2017).

The self has been studied within a wide array of disciplines, including psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, anthropology, sociology, and arts. The self is also at the center of class discussions by students and instructors eager to understand it better. As a matter of fact, the self can be a course subject in its own right, and some undergraduate and graduate university programs offer courses on the self.

This paper presents information about such a course, simply entitled “The Self”, created and taught by this author at the Department of Psychology at Mount Royal University in Calgary (Alberta, Canada). In what follows, I describe the course, its objectives, modes of evaluations, and main learning activities. Among the latter, every week, 20 students are invited to read one or two key papers pertaining to a central aspect of the self and to produce three questions inspired by the target text(s). The instructor organizes these questions and brings them to class for discussion. Here I look at the most representative weekly student questions from nine years of teaching this course and offer tentative answers to these questions. The questions and answers, I submit, greatly inform us on the most significant issues surrounding the self and allow for the identification of some recurrent messages about the self. The aim of this paper thus consists in tentatively answering the students’ questions as done in class based on what we currently know about the self and extract key lessons from this exercise.

1.3. Weekly Questions

1.3.1. Self-Awareness

(1) Can we be conscious without being self-aware?

Yes, very often we do, feel, or think things without explicit knowledge of these contents (Morin, 2006). Being conscious means being awake and responding to environmental stimuli (Natsoulas, 1983), as when one is driving and engaging in all proper responses such as changing lanes, maintaining speed, stopping at a red light, etc. One is immersed in experience without reflecting on the experience itself (“I”, self-as-subject; James, 1890). In contrast, being self-aware means becoming the object of one’s own attention and actively examining any salient aspects of the self (Morin, 2011a). To illustrate, the conscious driver suddenly realizes that (s)he is speeding—the driver is reflecting on his/her behavior (“Me”, self-as-object).

Whereas we can be conscious without being self-aware, it does not work the other way around—we cannot be self-aware while unconscious. In unconsciousness (i.e., sleep, coma) we are not processing information either from the environment or the self. (One exception could be lucid dreams, when one is aware of dreaming while non-conscious—Kozmová & Wolman, 2006). This distinction between consciousness and self-awareness potentially explains the main difference between human and non-human animals’ inner experiences (see next question A2).

(2) Are animals like my cat or dog self-aware?

This represents a highly controversial question, and no doubt the answer depends on how self-awareness is defined. So many articles and books have been written on this subject (e.g., Allen & Trestman, 2017; Edelman & Seth, 2009; Griffin, 2001), all informative but inconclusive in my opinion. Clearly, cats, dogs, horses, cows, pigs, birds, etc.—and even fish and insects—are conscious in the sense of being awake, experiencing internal states, perceiving the external world, and adequately responding to environmental stimuli. To illustrate, a tiger must be conscious when hunting a deer, as this activity entails wakefulness, hunger, processing of visual, auditory, and olfactive information, and carefully approaching the target.

Is the tiger self-aware? The general agreement is that non-human animals must possess some level of self-awareness—at least bodily awareness—to navigate the physical world adaptatively. The tiger must process information about the position and location of its body to approach and attack a deer successfully. Birds need bodily awareness (kinesthetic information) to flock together in harmony and avoid bumping into trees (Morin, 2012b). The contentious issue is: Are non-human animals aware of more abstract self-aspects (private self-awareness; Fenigstein, 1987) such as their emotions, sensations, goals, needs, and memories? Here it is important to recall the answer provided to question A1 above. The tiger may be experiencing hunger (consciousness) without knowing about it (self-awareness). Pet owners regularly comment on mental states of their pets such as when saying “My cat is happy”, which is problematic. The cat may be experiencing positive internal states such as food satiation, but to claim that the cat is “happy” implies that it knows that it is feeling good—which is virtually impossible to verify. Furthermore, a state of happiness is not required to explain the cat’s behavior of (say) purring: Satiation itself is sufficient.

When raising difficult questions that can’t readily be backed up with observable evidence, such as the current one, scientists must abide to Occam’s razor and select the simplest explanation available. Why is my dog all happy to see me coming back from work? A complicated, mentalistic account could be that the dog has been feeling lonely and has anticipated your return with excitement. A simpler, more mechanistic answer could be that the dog came to associate its owner with food via classical conditioning and is behaviorally getting ready to be fed. Unless proven wrong, the second option is the most scientifically viable. Concluding remark: There is no known valid and reliable way to confidently answer the question. The answer will likely depend on the anthropomorphic inclinations of the person answering.

(3) Why is it that self-awareness is considered by some researchers as being highly beneficial, and by others as being detrimental to mental health?

Self-awareness does not represent a unitary construct. A classic distinction between self-reflection and self-rumination was introduced by Trapnell and Campbell in 1999. Self-reflection constitutes a healthy form of self-focus where the person is intrigued by one’s own self and seeks self-discovery. This is a non-anxious form of philosophical curiosity toward oneself. Self-reflection is associated with positive outcomes which include successful Theory-of-Mind (ToM; thinking out what others may be experiencing inside), self-regulation (i.e., becoming the person one wants to become), and self-knowledge (knowing who you really are). In contrast, self-rumination is made up of self-doubts and negative self-appraisals that are repetitive and uncontrollable (Smith & Allow, 2009). It is linked to negative outcomes such as anxiety, depression, ineffective self-regulation, and escape from the self via self-destructive behaviors. The self-ruminating person is said to be in a “self-absorbed” state which impedes ToM, as (s)he is uniquely interested in one’s miserable reality—not that of other persons (Joiremann et al., 2002). It is impossible to make sense of research results pertaining to self-awareness without keeping in mind this distinction between self-reflection and self-rumination.

(4) Are there specific personality traits associated with self-awareness?

Absolutely. But here again, the distinction introduced above in the answer to question A3 prevails, as self-reflection and self-rumination are predictably associated with opposite traits. As a reminder, personality traits represent characteristics that are stable across time and situations (Feist et al., 2012). As well, it is customary to use the Big 5 Model of Personality developed by MacCrae and Costa (1989). That model posits that we all differ on five universal dimensions: Openness to experiences (O), Conscientiousness (C), Extroversion (E), Agreeableness (A), and Neuroticism (N, i.e., anxiety). In simple terms, individuals who are more self-reflective score relatively high on O (they are open to learn about themselves), C (they self-regulate more and are thus reliable), and A (they engage more often in ToM, which implies taking others’ perspective, and are thus kinder and more respectful). Self-ruminative people score relatively low on O, C (poor self-regulation), and A (impeded ToM) but high on N. (See Trapnell & Campbell, 1999.) To our knowledge, E is not meaningfully linked to both forms of self-awareness.

(5) If a person was raised in total isolation, as in the case of Genie the feral child, how would this affect self-processes?

It is important to emphasize that the self represents a social construct which gradually develops via social comparison (gaining knowledge about our personal characteristics by comparing ourselves to others) and social feedback (others sharing with us their views of ourselves). Furthermore (as will be discussed with questions B2 and D3), inner speech is used in the form of internal verbal conversations we address to ourselves to gain insight into who we are. Inner speech emerges out of social speech (Vygotsky, 1943/1962), so that without social interactions leading to the development of social language, inner speech would not develop.

Let’s imagine the following fictive scenario. Michelle was born 50 years ago from parents who were mad scientists. They decided to raise her in total isolation right from birth to see what would happen. She was thus placed in an empty room only containing a toilet, shower, and bed, and was fed through a hole three times a day; no one ever talked to her.

What kind of self-processes would Michelle have developed?

None whatsoever. Without social comparison and feedback or inner speech, Michelle would barely have a self and would be incapable of reflecting on it anyway. Since self-reflection constitutes a prerequisite for all other self-processes (see Morin, 2017,

Figure 1, as well as questions D1 and E1), Michelle would not engage in ToM (one can’t conceive of mental states in others without knowledge about one’s one internal states), self-regulation (one cannot change the self if one is oblivious of one’s self), self-description, mental time travel, self-knowledge, self-concept, and ultimately self-esteem (one cannot evaluate one’s worth in the absence of information about oneself). Thus, social isolation means the negation of self-processes. Social interactions are required for a self—and knowledge about it—to emerge.

1.3.2. Mindfulness / Self-Knowledge

(1) I am confused. The article uses terms like mindfulness, self-reflection, and self-knowledge—what are the differences between them?

There are several differences between these terms. Mindfulness refers to non-evaluative focus on the self in the present (Carlson, 2013); one is here, in-the-present, being aware of any salient self-aspects (e.g., bodily sensations, emotions) without asking questions about what is causing the experiences, what they could do or mean, etc.; just pure neutral self-observation. Carlson further clarified that mindfulness involves “decentering”—watching oneself from a third-person perspective, thus adding a distance between the self and its inner experiences (personal communication, January 20, 2014). Other qualities of mindfulness include self-compassion, that is, observing the self in an accepting way without resisting anything that might be observed, nor trying to change experiences or reacting to them with thoughts or actions. Questionnaires assessing mindfulness as a disposition usually contain subscales representing sub-dimensions such as present awareness and acceptance (e.g., Cardaciotto et al., 2008).

With self-reflection, the person actively (as opposed to passively) identifies, organizes, classifies, consolidates, questions, stores, and retrieves information pertaining to the self (Morin, in press [a]). Although healthy (Trapnell & Campbell, 1999), self-reflection allows critical self-evaluation and mental time travel (i.e., thinking about the past and the future, not just the present). Because of its more active and cognitive nature, self-reflection relies on inner speech whereas mindfulness aims at silencing the inner voice (Hussain & Shah, 2020). Self-knowledge represents actual genuine information about oneself (Carlson, 2013)—that is, information (e.g., about one’s personality traits) which can be corroborated by others. This is to be distinguished from the self-concept, which is defined as who we think we are, irrelevant of the accuracy of the information (Morin, 2017). To illustrate, a schizophrenic patient might see him/herself as possessing grandiose qualities that most surrounding individuals would dismiss. The patient does exhibit a self-concept, but because it is unrealistic, s(he) lacks self-knowledge. Hence, the two terms must not be equated.

(2) The article claims that mindfulness increases self-knowledge—is that true?

To her credit, Carlson (2013) presents creative and detailed research suggestions aimed at testing ways in which mindfulness might help overcome two main barriers to self-knowledge. These obstacles are informational barriers (things that are difficult to objectively apprehend, e.g., mannerisms) and motivational barriers (threatening things we don’t want to know about, e.g., selfishness). Her main hypotheses are that mindfulness should lower these barriers by increasing our ability to sustain attention on the current moment, thus processing more information; as well, the non-evaluative nature of mindfulness should reduce reactivity and defensiveness to ego-threatening information.

While the above hypotheses certainly sound reasonable, there are three key reasons to question the role of mindfulness in self-knowledge. (a) Because mindfulness exclusively focuses on the present, it ignores two important sources of self-knowledge: One’s recall of past significant personal events (autobiography) and one’s projection into the future (prospection). Remembering how we acted or felt in the past permits the detection of recurrent patterns that are informative (see Vanderveren et al., 2017). For example, “Each time I was in a new intimate relationship, I always worried that my partner could be having an affair… perhaps I am jealous”. As well, imagining what we might become in the future allows for the identification of personal goals that shape who we indeed become (Markus, 1983). (b) Because mindfulness is non-judgmental, it ignores the role of self-evaluation and self-criticism in the acquisition of self-information. For instance, one can learn that one is tardy by admitting lateness on several appointments. (c) As seen above, mindfulness inhibits inner speech. The fact that inner speech plays a crucial role in many self-processes leading to self-knowledge (see Morin, 2017,

Figure 1), such as self-reflection, self-description, and self-criticism, questions the link between mindfulness and self-knowledge.

In her paper, Carlson (2013) laid the foundation of an entire research program on mindfulness and self-knowledge. Yet, intriguingly, there is no published research on this topic past 2013. Either herself and others lost interest in this line of research, or attempts made at testing Carlson’s hypotheses failed. If the latter is accurate, possible causes of unsupportive results could be those outlined above.

(3) Does self-knowledge fluctuate throughout the lifespan, or does one’s level of self-knowledge typically remain stable over time?

The main intrapersonal process leading to self-knowledge is self-reflection. Self-reflection is mostly conceived as a stable personality trait (Fenigstein et al., 1975) and thus does not noticeably fluctuate in time. However, temporary states of self-focus induced by environmental stimuli (e.g., exposure to a mirror or an audience; Carver & Scheier, 1978) may vary across time. Similarly, instances of interpersonal processes such as social comparison and feedback may be more or less frequent depending on one’s immediate social environment. The result of these somewhat mutable processes and events is a gradual gain in self-information which translates into self-knowledge. What is progressively acquired is permanently stored in memory and remains intact as we age. Actually, self-knowledge is remarkably resistant even in cases of dementia or brain damage (Klein et al., 1996). One analogy could be that our knowledge of the world increases when we take classes, but it nonetheless keeps increasing throughout our life and stabilizes at one point.

(4) What are the possible consequences of a lack of self-knowledge?

Self-knowledge deficits can have very disagreeable effects. Imagine John, who thinks he likes the color yellow and decides to buy a yellow car—only to realize days after the purchase that he dislikes the car because of it color. Or picture Tomas, who goes ahead and gets a huge mortgage on a house he thought he would like—only to comprehend days or weeks after the banking transaction that he is now living in a house he hates. Consequences of faulty self-understanding can be even more dramatic, such as when one pursues the “wrong” career path because of inadequate knowledge of one’s goals and skills, or when one keeps being involved in doomed intimate relationships because one doesn’t know who the “right” partner should be.

Lack of self-knowledge basically signifies a distorted self-view, which is associated with bragging (as one overestimates of one’s strengths), unrealistic choices, poor academic performance, and lower life satisfaction (Carlson, 2013). In contrast, knowing oneself well leads to realistic decision-making pertaining to key aspects of one’s life, including selection of compatible intimate partner and friends, education and career orientations that fit one’s goals, realistic choices about housing and geographic locations, and much more. And as alluded to in the answer to question B2, self-knowledge facilitates self-regulation because it contains information about one’s goals, standards, and strategies to be used to shape one’s behavior in desired directions (Markus, 1983). Thus, a lack of self-knowledge will likely impede self-regulation.

1.3.3. Mental Time Travel (MTT)

(1) I am confused. What are the differences between MTT, imagination, mind wandering, daydreaming, and planning?

These terms all potentially imply past or future thinking but differ in important ways. MTT refers to cognitively remembering one’s own past (episodic memory; autobiography) and imagining one’s own future (prospection; episodic future thinking). By definition, MTT is always about oneself. Any past/future thinking which is not about the self is not MTT. Take imagination as a case in point, which constitutes the faculty of forming new ideas, images, or concepts of something not present to the senses (Imagination, 2023). If one is imagining something that pertains to one’s life in the future (e.g., how an upcoming class presentation will go) or in the past (e.g., swimming for the first time), then one is essentially engaged in prospection and autobiography, respectively. If one is imagining a totally fictive scenario not directly related to oneself (e.g., first contact between humans and an alien race), or imagining something self-related in the present (e.g., what food to eat now), then these exercises in imagination are not MTT. Mind wandering and daydreaming (largely synonyms) constitute arbitrary thoughts experienced when engaged in attention-demanding tasks (Schooler et al., 2011), as when one catches oneself thinking about something unrelated to the book one is reading. Since both may occur in the present and be non-self in nature, they must not be equated with MTT. Finally, because making plans for something (Planning, 2023) is unavoidably about the future and most usually about ourselves, this suggests that planning represents a special case of prospection. However, if the planning is not associated with the self, as when a travel agent plans an itinerary for a client, then it is not prospection.

(2) What happens when someone loses the ability to think about his/her own past?

Loss of access to one’s memories following brain insult or dementia reliably results in prospection deficits (Addis & Schacter, 2008). In other words, prospection heavily relies on episodic memory because the latter provides building blocks from which episodic future thoughts are constructed (e.g., Schacter et al., 2017; Tulving, 1985). To illustrate, one can foresee what an upcoming trip will look like based on memories of past trips; without these memories, it would be very hard to imagine what any future trip could be like—although one could still use semantic information gathered in travel books and such.

Evidence of a solid causal link between autobiography and prospection includes the observations that patients characterized by poor episodic memory (as in depression and schizophrenia) exhibit difficulty in imagining their future (Szpunar, 2010), and common brain activations are recorded when participants engage in autobiographical and prospection tasks (Schacter et al., 2017).

(3) What is the purpose of episodic future thinking and how does it benefit us?

Prospection serves an important survival function as it allows us to set future goals, plan, self-regulate, and ultimately reach these goals—thus becoming who we want to become. In short, episodic future thinking guide our behaviors in adaptative ways. For example, John could envision himself suffering from lung cancer because of smoking (prospection), and so he decides to quit smoking now (self-regulation). Or Martin might see himself as a successful lawyer in 10 years and enrolls in law school to get a degree.

(4) For people who suffer from depression, are episodic future thoughts more positive, negative, or neutral in nature? What about in anxious people?

Research shows that when depressed individuals think about their future, they tend to report less details in imagined positive experiences compared to neutral or negative ones. Specifically, simulated future events exhibit less detail/vividness, less use of mental imagery, less use of first-person perspective, and less plausibility/perceived likelihood of occurring. This suggests a reduced anticipation of a pleasurable future (e.g., Hallford et al., 2020), which is obviously consistent with depression. Moustafa and colleagues (2019, p. 7) propose that depressed people might struggle to imagine a good future because they struggle to remember a good past. On the other hand, the same research group observed that anxious people have a greater difficulty at generating positive and negative future events, possibly as a means of controlling anxiety via reduced anticipation of future events in general.

(5) Why is it that healthy people tend to be optimistic when they imagine their future?

Human beings are remarkably optimistic, and this colors their imagining of the future. The main reason for this is that viewing our future as good and pleasant motivates us to keep going and working at attaining our future goals. Simply put, if we were pessimistic about our future, we would stop acting, or at least we would do less, thus harming our motivation to evolve and succeed. (See the answer to question C3.)

1.3.4. Theory-of-Mind (ToM)

(1) Two weeks ago we studies self-awareness. What is the connection between self-awareness and ToM?

The most accepted view is that self-reflection (the healthy form of self-awareness) causally leads to (precedes) ToM. Self-reflection allows one to apprehend one’s inner experiences and to imagine the existence of similar experiences in others. This refers to the Simulation Theory: People mentally simulate what others might be internally experiencing by imagining what types of experiences they, themselves, might have if in a comparable situation (Focquaert et al., 2008). Recall however, that self-rumination impedes ToM as one is too absorbed in one’s (negative) experiences to bother considering others’ experiences. (See the answer to question A3.)

Here is an example of the Simulation Theory: Robert goes to the dentist for a root canal procedure; as the dentist proceeds, Robert is aware of several perceptions (most being unpleasant) such as the needle penetrating his gum, the taste of the freezing agent being administered, the vibrations produced by the drill, the overall post-procedure sensation—and so forth (self-reflection). Several weeks later, Robert meets with Ruth who tells him that she just got back from the dentist. Robert expresses his sympathies, tells her that he knows exactly how she feels (ToM) because he too went through a similar experience not long ago (simulation). Then perhaps Robert offers Ruth some ice cream to make her feel better (helping behavior).

Empirical evidence in support of the Simulation Theory is overwhelming: (a) the more people are effective at self-reflection, the better they are at reading others’ minds (Dimaggio et al., 2008); (b) self-reflection interventions in schizophrenic patients precede ToM improvement (Lysaker et al., 2007); (c) there is an important overlap in brain activity when participants work on self-reflection and Theory-of-Mind tasks (Keysers & Gazzola, 2007); (d) traumatic brain injury patients who exhibit self-reflection deficits also show ToM impairment (Bivona et al., 2014). Note that despite these compelling observations, some (e.g., Carruthers, 1996) argue that ToM leads to self-awareness—not the other way. Another view is that self-reflection is required for the emergence of ToM but not for its online use. That is, once fully developed based on introspection on one's own mental states, ToM could take a life of its own and not necessitate constant introspection when reflecting on others' mental states (Morin, 2003).

(2) What would happen if we would all lose our ability to engage in ToM overnight?

The answer to this question emphasizes the formidable importance of ToM. One could argue that without ToM, the End of the World would ensue within a few weeks or months. ToM allows for the development of at least some understanding of others’ reality; without such an understanding, the world would collapse. ToM represents the ability to attribute mental states (e.g., goals, intentions, beliefs, desires, thoughts, feelings) to others (Frith & Frith, 2003). It serves several key functions, among which smooth social interactions, prediction of others’ behavior, helping behavior and cooperation based on empathy toward others, detection of, and engagement in, deception to gain an advantage over others in a competitive environment, cheating when necessary, and avoidance of others when threatful intentions are perceived (Malle, 2002). Without ToM, we could not effectively communicate with one another (Krych-Appelbaum et al., 2007), as a basic knowledge of the communicator’s perspective and implicit underlying information about what (s)he means are required. In short, ToM is required for survival of the species.

(3) Is language (including inner speech) important for ToM?

Several researchers maintain that ToM depends on the acquisition and use of language (e.g., Milligan et al., 2007; Strickland et al., 2014). Indeed, both phenomena emerge at about the same time, between 3 to 5 years of age. Language is associated with ToM because early social interactions—themselves instrumental in ToM development (Lee & Hobson, 1998)—involve verbal conversations between the child and caregivers (Harris et al., 2005). During such conversations, caregivers may disclose their own inner experiences and ask about others’ mental states (e.g., “How do you think your friend feels about this?”), thereby motivating the child to take others’ perspective. As well, language allows for the development and use of a complex set of verbal labels (vocabulary) about our own and others’ feelings, thoughts, desires, beliefs, etc. This labeling of mental states facilitates their identification and differentiation (Morin, 2018). It is postulated that conversations and label use get internalized via inner speech (Vygotsky, 1943/1962), and that we continue to internally verbalize about (ours and) others’ mental states in adulthood (see Fernyhough & Meins, 2009). To illustrate, think of the many occasions when we internally verbalize to ourselves statements like “Did I hurt her feelings?”, “Why did he say that?”, “Tomas lost his cat and probably feels sad”, and so forth. In support of the above, individuals on the autism spectrum who are known to exhibit ToM deficits also show an underuse of inner speech (e.g., Williams & Jarrold, 2010).

(4) How would ToM in a narcissist or psychopath differ from the normal person?

At first glance, one would assume that both narcissistic and psychopathic individuals lack ToM skills, accounting for their absence of guilt or remorse following acts hurting other people. A closer inspection rather suggests that these individuals may possess one form of ToM and be deficient on a second type of ToM. This distinction is based on the notion of cold and hot cognition (see Zimmerman et al., 2016). “Cold”, cognitive ToM refers to calculated thinking about others’ mentals states, sometimes at the service of deception. For instance, a psychopath could wonder when a target person will leave the house in order to rob its content. Cold ToM is known to recruit higher executive functions relying on cortical areas. “Hot” ToM on the other hand, is involved when we emotionally connect with feelings of other persons, allowing us to exhibit empathy. What the psychopath is unlikely to do is think about the distress the robbed person will experience. Indeed, what prevents most of us from hurting others for personal gain is the empathy part of ToM. Hot ToM is associated with activations of subcortical brain areas subserving processing of emotional information.

(5) One of the articles mentions that females are better than males at ToM—why is that?

One first thing that must be kept in mind is that females’ advantage at ToM compared to males is statistically small—it would be wrong to claim that females “excel” at ToM and males show “poor” ToM performance. This being said, these gender differences might steam from socialization practices (see Carter, 2014), where typically, females are encouraged to focus more on their emotions and to express them more freely. To simplify, it seems that girls are taught to “internalize” by analyzing their inner experiences to a greater extent, as well as share these states with others. Instead, boys tend to “externalize” more via showy display of their internal states (e.g., aggression in sports). Females’ greater introspective disposition essentially amounts to more self-reflection, which in turn possibly means more simulation of others’ mental states—hence the ToM advantage (recall the Simulation View discussed in question D1). Another complementary possibility is that most of the above is linguistic in nature (i.e., interpersonal conversations) and gradually get internalized via inner speech, which is known to positively sustain self-reflection and ToM (see question D3). Arguably, females tend to be more verbal than males (see Adani & Cepanec, 2019).

(6) Do animals possess ToM?

As for question A2 regarding animal self-awareness, this is a contentious issue. Let’s start by acknowledging that like self-awareness, ToM does not represent a unitary construct and most likely involves levels, so that it is not an all-or-none phenomenon. Let’s also agree that animals must possess at least some primitive form of ToM, otherwise they would not survive (question D2). A basic understanding of other animals in terms of behavior prediction (i.e., deception, cooperation) is required for survival. Thus, the question rather is: Up to what point do animals exhibit ToM abilities?

Some researchers impute almost human-like ToM to primates (e.g., Gallup, 1985) based on anecdotical observations made in the wild. Designing convincing experiments under controlled conditions is remarkably difficult (see, e.g., Premack & Woodruff, 1978; Povinelli et al., 1990), as non-mentalistic interpretations can often explain what seems to represent instances of ToM (Hare et al., 2001). In their literature review, Call and Tomasello (2008) propose that chimpanzees can understand goals, intentions, perceptions, and knowledge in other conspecifics—but not their beliefs. In a typical experiment on intention understanding, chimps observe a human experimenter trying to turn on a light with his head as his hands are occupied holding a blanket. The animal reacts to this not by imitating the experimenter’s behavior (i.e., turning on a light with its head), but instead by imitating the intention behind the action—by turning on the light with its hands. Povinelli and Vonk (2003) suggest that chimpanzees form mental concepts of visible, concrete objects in their environments (e.g., trees, facial expressions, other chimpanzees), but not about unobservable things such as God, gravity, or love. When engaged in ToM, chimpanzees would reason about the statistical regularities that exist among certain events and the behavior, postures, and head movements of others (behavioural abstractions), but not about others’ covert mental states.

What kind of ToM do other non-primate animals possess is unknown. One can assume that at least an online, quick—as opposed to an offline, deliberate—version exists for survival purposes. Pet owners often utter things such as “My dog knows when I am sad”, which would be a clear case of ToM—empathy to be more precise. Multiple animal behaviors may look like they imply ToM on the surface, but in most cases a non-mentalistic explanation can be offered. In the example above, it is very possible that the dog has gradually learned to walk toward its owner’s when (s)he is crying because such approach response was reinforced in the past (that is: Owner cries > dog approaches > owner pets dog > dog is reinforced). Thus, apparent instances of ToM in non-primate animals can be understood in terms of classical and operant conditioning. Let us recall Occam’s razor discussed in the answer to question A2: Always select the simplest explanation obtainable.

1.3.5. Self-Regulation

(1) Four weeks ago we studies self-awareness. What is the connection between self-awareness and self-regulation?

As defined in the reading (Baumeister & Vohs, 2003), self-regulation consists in altering one’s behavior, changing one’s mood, selecting response from options, and filtering irrelevant information. In essence, self-regulation refers to the control of one's behavior, emotions, and thoughts in pursuit of long-term goals. A general principle is that we cannot change, alter, select, and filter things about ourselves we are oblivious of. Thus, self-awareness (specifically self-reflection) represents a prerequisite to self-regulation, as one must be cognizant of what self-aspects need to be modified before effective cognitive-behavioral control can occur (e.g., Mikulas, 1986). Importantly, self-regulation heavily relies on standards as well as comparisons between the ”real” self (who one currently is) and the “ideal” self (who one wants to become) (Carver & Scheier, 1981). Such comparisons require self-reflection. The importance of self-reflection in self-regulation is emphasized by Bandura (1991), who views the former as the first step in the latter. Note that basic animal self-control (see question E4 below), such as when a dog refrains from biting another dog, most likely does not require self-reflection (see Miller et al., 2010) and instead relies on instinctual responses.

This is the third of several instances (see Morin, 2017,

Figure 1) where self-reflection causally precedes another self-related process: Recall self-knowledge and ToM. Consistent with the above, inner speech, which is active during self-reflection (Morin, 2018), is also importantly recruited during self-regulation, suggesting the following causal chain: Self-reflection > inner speech > self-regulation. A large body of research based on Vygotsky’s ideas (1943/1962) shows that private speech (out loud self-directed speech in children) causally influences several self-regulatory outcomes (Alderson-Day & Fernyhough, 2015; Winsler, 2009). For example, performance of children on the Tower of London task (a measure of planning, which represents an important part of self-regulation) is lower when private speech is blocked using articulatory suppression (Lidstone et al., 2010). Articulatory suppression is achieved by having volunteers repeat a word over and over (or counting backward from 100), thus interfering with the ability to emit self-verbalizations. Also employing articulatory suppression, Tullett and Inzlicht (2010) observed self-control deficits in adults on a “go/no-go” task. Meichenbaum and Goodman (1971) designed a self-instructional training procedure aimed at developing inner speech use and showed a reduction of impulsive behavior in children. And Duncan and Cheyne (2001) observed more private speech produced by young adults when working on a difficult task as opposed to an easy one; note that problem-solving also constitutes an important part of self-regulation.

(2) What happens when we fail at self-regulation?

Consequences of self-regulation failures are not trivial and echo those of self-knowledge deficits. Research shows that self-regulation failure is associated with a host of negative outcomes such as violent behavior and anger issues, addiction, poor health (e.g., obesity), impulse buying and financial problems, poor decision making (e.g., unsafe sex), under-achievement, relational problems, and low self-esteem (see Molden et al., 2016). Opposite outcomes are associated with effective self-regulation. Vivid examples of self-regulation failures include spending large amounts of money purchasing pricy items online, having unprotected sex with one’s best friend’s husband/wife, and physically harming another person in a conflict situation.

(3) Are there psychological disorders associated with self-regulatory problems?

This question nicely complements the previous topic addressed in question E2. Indeed, multiple psychological disorders are linked to self-regulatory difficulties. As a case in point: Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Shiels & Hawk, 2010), because attention, like self-reflection, represents a prerequisite to self-regulation. The same applies to addiction, defined as the inability to prevent oneself from continuing using (Baumeister & Vonasch, 2015), as well as binge eating. Additional examples are depression (self-rumination interferes with self-regulation), bipolar mood disorder (during a manic state, individuals experience problems regulating their extreme positive emotions), and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). In this last case, the person experiences intense mood swings and feels uncertainty about how to perceive oneself. Feelings for others can change quickly and swing from extreme closeness to extreme dislike. These changing feelings can lead to unstable relationships and emotional pain. Thus, a significant part of BPD is a difficulty in regulating one’s emotions (Bornovalova et al., 2008).

(4) I wonder if there is a difference between self-regulation and self-control.

There is no universally accepted distinction in the scientific community between self-regulation and self-control; both terms are frequently used interchangeably. However, for clarity purposes, one can conceive of self-regulation as being a broader process made up of multiple narrower self-control efforts. Self-regulation is long-term (e.g., days, weeks, months, years) and entails executive functions such as working memory (i.e., inner speech), planning, and decision-making. An example could be getting a university degree, which takes years and requires foresight, discipline, organization, and perseverance. The student must take many crucial decisions such as what courses to take and in what order, how and when to study and work on assignments, how and when to pay tuition fees, and so forth.

Instead, self-control is short-term (e.g., minutes or hours) and implies delay of gratification (“Chocolate only after dinner”) and resisting temptation (“Only one piece of chocolate”) in the pursuit of long-term goals (e.g., weight management). The student who forces him/herself to keep studying instead of watching a television show (“I’ll watch the show only after 30 minutes of studying”) is effectively engaged in self-control. The same student will need to repeatedly exert self-control efforts throughout the larger self-regulatory process of obtaining the degree, such as when declining to go to a party to write an essay instead or saving money here and there to afford tuition.

1.3.5. Inner Speech

(1) There are so many terms used to designate inner speech, such as private speech, self-talk, internal dialogue, self-talk, or propositional thought—are there differences between these terms?

The use of different expressions to designate the same construct is deplorable as it adds confusion and complicates literature searches. That is, on must include all existing terms such as inner speech, propositional thought, self-verbalization, self-directed speech, self-statements, silent verbal thinking, phonological loop, or subvocal speech in search engines to capture what is known about the phenomenon. The umbrella term “self-talk” constitutes the activity of talking to oneself out loud or in silence (Brinthaupt et al., 2009). The latter is usually named “inner speech”, defined as the capacity to produce language silently in one’s head (Fama & Turkeltaud, 2020). But there are some differences between these labels. For example, “internal dialogue” refers to self-directed speech made up of back-and-forth comments to oneself, as when one converses with another person (see Puchalska-Wasyl, 2015), whereas “internal monologue” signifies self-talk in which one talks to oneself as one person. “Private speech” describes self-talk emitted out loud by children in social situations without preoccupation of being understood by others (Winsler, 2009). Note that Piaget (1926) favored the term “egocentric speech”, suggesting that private speech represents an immature manifestation of cognition. This idea was in sharp contrast with Vygotsky view (1934/1962) that private (and later inner) speech play an important self-regulatory function (see questions E1 and F3).

(2) I sometimes talk to myself out loud—is this normal or am I crazy?

You are not crazy! As long as the self-talk is emitted when alone, it is perfectly normal and actually healthy as it serves important cognitive functions (see question F3 below). Private speech in adults differs from that of children in that it is not carried out in the presence of other persons—although one can be caught talking to oneself out loud by an inadvertent observer. Adult private speech has long been negatively perceived most likely because of its association with schizophrenics’ or alcoholics’ incoherent self-verbalizations in public. That adult private speech is “crazy” is a myth, as demonstrated by Duncan and Cheyne (1999), who developed a private speech scale and administered it to a large sample of healthy young adults. They found that a substantial amount of private speech was reported by the participants. Unlike the developmental trajectory of private speech in children (see Kohlberg et al., 1968), nothing much is known about several issues such as individual differences in adult private speech. What is known is that frequency of private speech reliably increases when people are confronted to new or difficult tasks (John-Steiner, 1992) (e.g., “Where am I supposed to plug this wire” when installing a novel and complicated sound system). Incidentally, Vygotsky (1943/1962) maintained that once well internalized as inner speech at adolescence, private speech ceases to exist; the evidence presented above does not support this assertion.

(3) What would happen if I had a stroke and loss my inner voice?

The void felt by the absence of our inner voice would be dramatic. The question above is precisely what happened to Jill Bolte Taylor, as detailed in her 2006 book and analyzed in Morin (2009). Jill suffered from a left hemispheric stroke caused by a congenital arteriovenous malformation which led to a loss of inner speech. Several of her self-processes were altered—for instance, deficits in corporeal awareness, sense of individuality, retrieval of autobiographical memories, and self-conscious emotions. This is consistent with the view that inner speech serves important self-reflective functions (Morin, 2018), as already expressed multiple times in this paper.

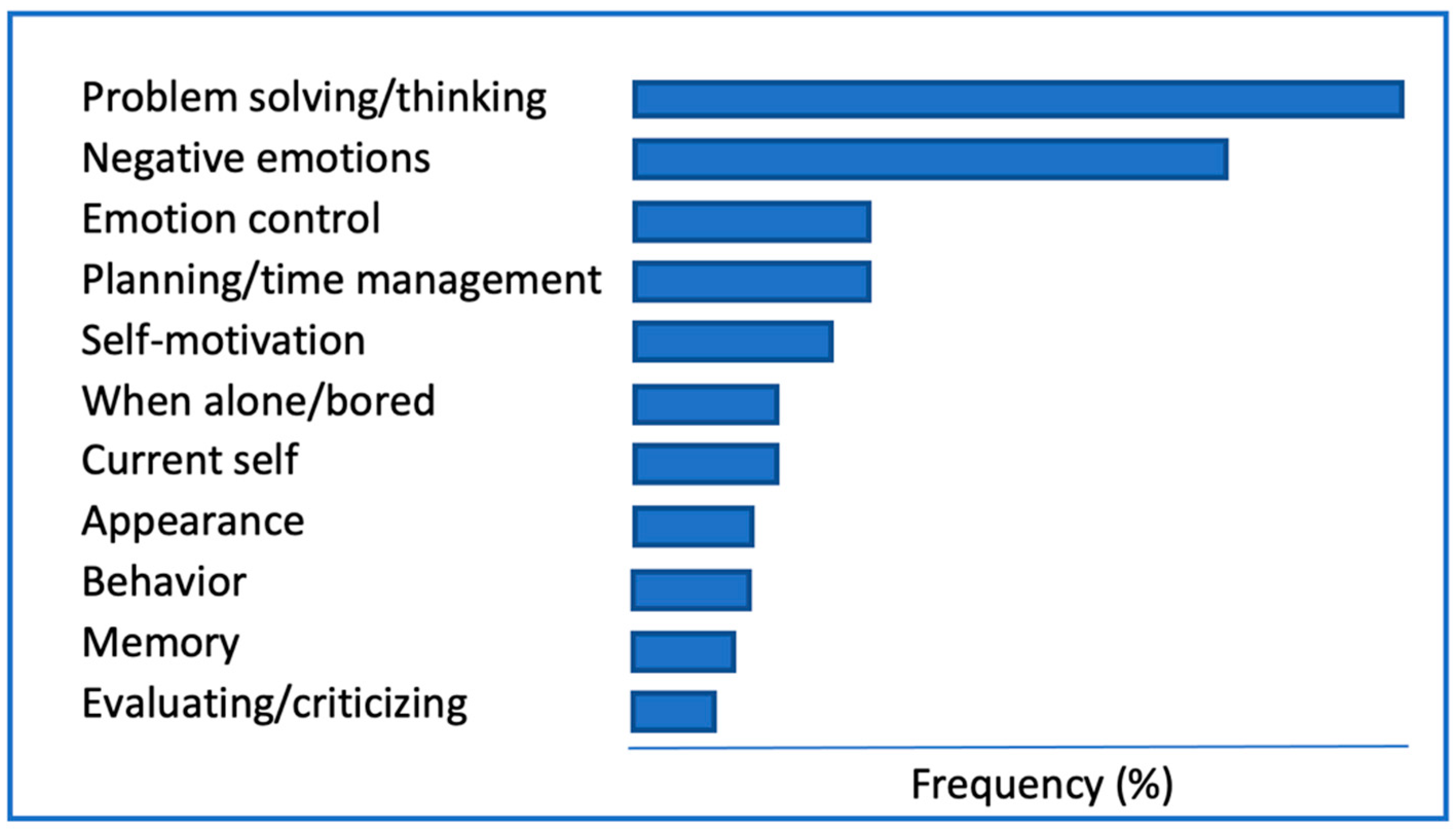

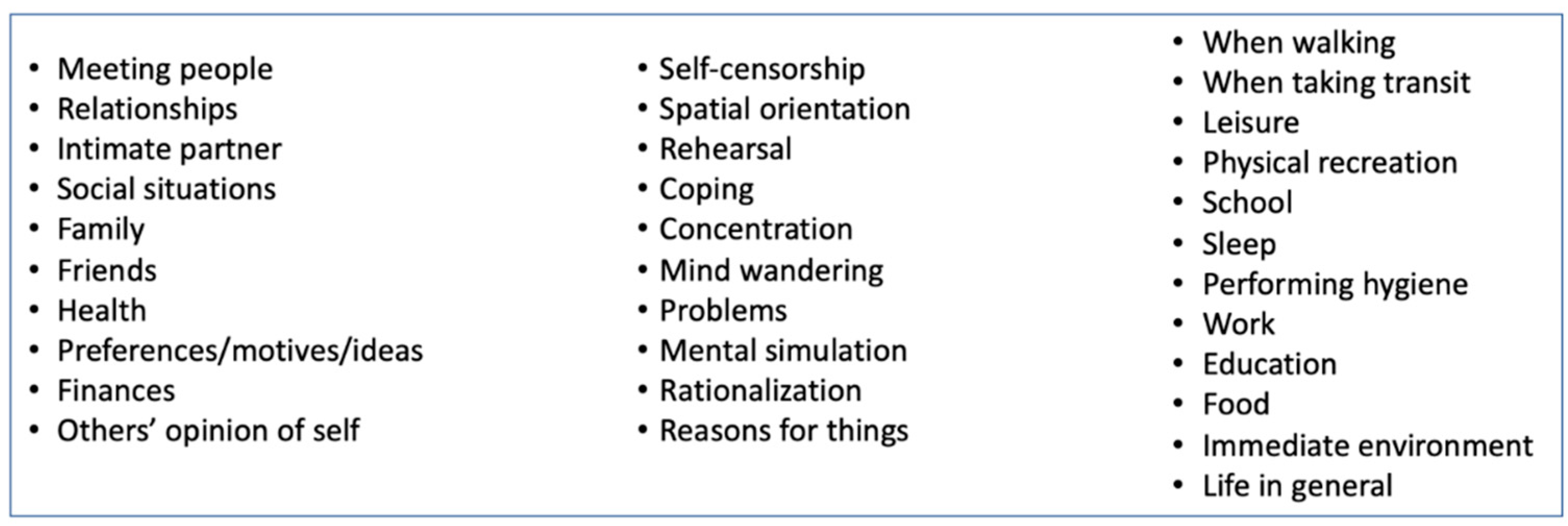

Another way to answer the question consists in looking at what people report typically taking to themselves about and imagine a psychological world without these contents. In our work (e.g., Morin et al., 2018; Morin & Racy, 2022), we use an open-format measure aimed at collecting self-reported instances of naturally occurring inner speech in response to three probes: I talk to myself about (topics), when (during activities), and in order to (functions). Volunteers (students) freely list their recalled inner speech topics and functions, as presented in

Figure 1 below.

Table 2 displays less frequently reported contents.

Figure 1.

Most frequently self-reported inner speech instances (adapted from Morin & Racy, 2021).

Figure 1.

Most frequently self-reported inner speech instances (adapted from Morin & Racy, 2021).

Now, picture yourself not being able to talk to yourself about all these multiple themes and for such various reasons: A mind without its inner voice would be very silent and lonely indeed, suffering from severe self-reflective, self-regulatory, and cognitive deficits.

(4) How often do we talk to ourselves? Is it possible to have no inner voice?

It is very difficult to estimate inner speech frequency. Hurlburt and colleague (e.g., Heavey & Hurlburt, 2008) used the Descriptive Experience Sampling (DES), which relies on a beeper that randomly cues participants to report whatever inner experiences they had just before the beep. Participants reported experiencing inner speech about 20% of the times they were probed, with important individual differences ranging from 0% (no inner speech) to 75%. This team reports a much higher inner speech frequency (over 70%) using a self-report scale they developed (the Nevada Inner Experience Questionnaire; Heavey et al., 2019). One explanation offered is that the DES method entails training and practice likely to increase participants’ understanding of what inner speech is and is not, whereas the self-report approach does not, leading to an overestimation by volunteers using the latter.

Thus, it appears that we do talk to ourselves a lot. Note that as seen above, some people report experiencing no inner speech at all. Do these individuals have a silent mind as alluded to in the answer to question F3? Perhaps, but more probable, they do experience inner speech but don’t know about it. This “silent mind” issue is currently hotly debated in several blogs on the internet.

(5) Do babies or animals have inner speech?

Few self-related questions can be answered with high scientific confidence. Exceptionally, this question can receive a straightforward and assured answer: No. It is an empirically well-established fact that social speech comes first, followed by private speech, and then inner speech. In other words, self-directed speech gets gradually internalized, from outer/interpersonal to inner/intrapersonal (Vygotsky, 1943/1962). One cannot possibly exhibit inner speech prior to acquiring social speech. Since babies and animals do not have social speech, they do not have inner speech.

1.3.6. Self and Brain / Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

(1) What are the main causes of TBI?

TBI results from a bump, blow, or jolt to the head, or a penetrating injury (e.g., a gunshot) to the head. This is important because it means that degenerative brain diseases such as Alzheimer or dementia, although they may lead to similar symptoms (including anosognosia; see question G2 below), are technically not TBI. Men and older adults are more at risk of suffering from TBI. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023), the most frequent causes of TBI are violence (including child, domestic, and war-related), transportation and construction accidents, sports, and falls.

(2) Are patients suffering from TBI in denial regarding their deficits, or are they truly unaware of them?

They are genuinely unaware of their deficits, which is called “anosognosia” (Prigatano, 2005). Anosognosia encompasses several forms of sensory, motor, perceptual, cognitive, and/or emotional disturbances (Rosen, 2011). The TBI patient who claims s(he) can tie his/her shoes or run without difficulty truly believes so—to the dismay of close ones who (literally) know better. TBI victims are not in denial (i.e., being cognizant of deficits but refusing to admit their existence), because they do not exhibit (or report) emotional distress or depression in light of their deficits. Instead, patients display a flat affect inconsistent with a realistic apprehension of the painful situation.

(3) Can we use self-report questionnaires to assess anosognosia in patients with TBI?

This is not advisable (Prigatano, 2005). By definition, TBI patients lack awareness of their condition; thus, their insight about it will likely be distorted and unreliable (i.e., overestimation of their skills and underestimation of deficits). Basically, self-report questionnaires rely on self-reflection, which is impeded in anosognosia. Better methods for assessing anosognosia (see de Ruijter et al., 2020) include objective measures of actual performance and asking close ones (e.g., family members, therapists) to rate patients’ performance. In the second case, a lack of convergence between self- and others’ performance ratings will likely be observed and signifies the presence of anosognosia.

(4) Why is it important to reduce anosognosia after TBI and how is it done?

It is critical to reduce anosognosia as much as possible for two main reasons. (a) The less patients are aware of the severity of their deficits, the less they will see a need for rehabilitation, and thus therapy compliance will be compromised. This in turn will reduce the likelihood of physical and cognitive improvement post-TBI. (b) TBI patients lack insight into their condition and may expose themselves to injuries when engaging in behaviors they cannot perform adequately. To illustrate, a patient might decide to go for a walk despite locomotion deficits and fall. In essence, anosognosia increases the chances of injuries—hence, the need to address it in therapy. Therapy consists in providing gradual and objective feedback to the patient regarding what s(he) cannot do as well as before the trauma (Prigatano, 2009). The feedback can be verbal or visual (i.e., using video recordings), and must be gentle and supportive to avoid emotional distress. Inviting patients to practice motor skills in a virtual reality environment represents an excellent approach (Muratore et al., 2019) because of the absence of risk if performance fails.

1.3.7. Self-Recognition

(1) One article sees self-recognition as being a good measure of self-awareness, and the other one disagrees. Can you explain?

The significance of mirror self-recognition for self-awareness started being debated in the literature as soon as Gordon Gallup Jr. published his first report of successful self-recognition in chimpanzees in the sixties (Gallup, 1968). Supporters of Gallup’s view (to be described below) include Julian Keenan, James Anderson, Alvaro Pascual-Leone, Lori Marino, and Mark Wheeler. Among critics, one can find Robert Mitchell, Daniel Povinelli, Cecilia Heyes, and this author (see Morin, 2010, 2021, for a summary of the debate).

Gallup’s interpretation of successful self-recognition is as follows (see Keenan et al., 2003). Exhibiting self-directed behaviors in front of a mirror suggests that the organism can take itself as the object of its own attention; the ability to self-focus represents a well-established constituent of self-awareness (Duval & Wicklund, 1972). Furthermore, re-cognizing oneself in front of a mirror assumes pre-existing ‘‘self-cognition’’ (i.e., a self-concept) and thus self-awareness. More specifically, Gallup and colleagues maintain that self-recognition entails knowledge of one’s mental states such as emotions, thoughts, motives, beliefs, and so forth. The main point made by opponents of this rationale is that the only prerequisite for self-recognition is information about one’s body—a non-mentalistic dimension of the self. All the self-recognizing organism needs is a kinesthetic representation of its own physical self, which is matched with the image seen in the mirror. (Additional evidence against Gallup’s view will be discussed in upcoming questions.)

Gallup’s interpretation as been taken as absolute truth by many, to the point that introductory or developmental psychology textbooks uncritically claim (for example) that children become self-aware once shown capable of self-recognition. The problem goes farther, as this interpretation is now being used to question the idea that inner speech is involved in self-awareness. To illustrate, Kohda and colleagues (2023) recently presented what they claim is evidence of self-recognition in fish. The authors’ construal of the evidence implies that since there is self-recognition in fish, then fish are self-aware; fish do not use inner speech, thus inner speech is not important for self-awareness. Clearly, such a reasoning ignores the large body of evidence in favor of the self-reflective functions of inner speech (notably, see question F3) and directly compares human and fish cognition, which is problematic (Morin, in press [b]).

(2) Is it possible for an organism to have self-awareness and yet fail the mirror test?

Absolutely. Blind individuals obviously won’t be able to self-recognize in front of a mirror despite intact self-processes such as self-reflection, self-knowledge, self-regulation, and MTT. Prosopagnosia represents a neurological condition characterized by the inability to recognize faces, including one’s own (Damasio, 1985). Patients suffering from prosopagnosia fail the mirror test (i.e., touching a mark on one’s face in front of a mirror) despite intact self-awareness. Note that the opposite is also true: It is possible to achieve self-recognition notwithstanding severe self-awareness deficits (see Morin, 2010), such as in down syndrome, autism, schizophrenia, and any other imaginable mental disorders for that matter. Self-recognition is remarkably resistant to disorders, diseases, and dysfunctions, and may be affected only in extreme cases of dementia. Indeed, self-recognition is established very early in development (between 18 and 24 months of age; Amsterdam, 1972) and is one of the last functions to go. The above further casts doubt on Gallup’s interpretation of self-recognition for self-awareness: How can these two processes be so intimately connected when there is clear evidence that the former can be observed in the absence of the latter, and vice versa?

(3) What animals can recognize themselves in a mirror?

It is not an overstatement to state that basically all living creatures have been tested for self-recognition. To date, non-human animals who have passed the mark test are chimpanzees, orangutans, bonobos, elephants, dolphins, magpies, jackdaws, and fish (see Anderson & Gallup, 2015). All other creatures have failed the test and/or do not emit self-directed behaviors in front of a mirror. Note that some animals seem unsuccessful at self-recognition not because they lack the ability but because they react to reflecting surfaces unlike most other animals. For example, gorillas avoid eye contact during social interactions—and thus dislike looking at their own reflection in a mirror (Murray et al., 2022). And no, cats and dogs do not recognize themselves in a mirror (Kim & Johns, 2022).

(4) Are there other measures of self-awareness in animals besides self-recognition?

One promising research avenue is the study of metacognition in animals (Smith, 2009). Metacognition represents knowledge about one’s own thinking processes—thinking about thinking (Fleming, 2021). One manifestation of metacognition is Uncertainty Responding (UR): Knowing that one does not know or might not remember something. When uncertain about something, we tend to decline responding or differ responding to seek more information. This indicates insight into our own thinking. For example, one could be asked when a specific event occurred; if one is uncertain about the date, responding could be delayed to check the information. Testing UR in animals involves asking subjects to discriminate between high and low tones (in auditory tasks) or high- and low-density images (in visual tasks); subjects must decide if a stimulus is higher (or lower) than another one. They are given the option of declining or delaying trials when the discrimination becomes too difficult, indicating UR when they do so (see Smith & Washburn, 2005). Apes, dolphins, and some monkeys seem to have metacognitive abilities.

It is important to keep in mind that metacognition represents only one facet of self-awareness; the demonstration of its presence in some animals does not mean that they possess other self-processes such as additional aspects of self-reflection, or MTT and self-knowledge.

1.3.8. Negative Self-Focus / Psychopathology

(1) Is there a difference between rumination and worry?

Both rumination and worry represent repetitive, uncontrollable, and negative thoughts. An important difference is that rumination is always about the self (hence “self-rumination”), especially one’s past or expected failures, whereas worry may be non-self (Worry, 2023), as when one worries about another person’s poor health or a hurricane devastating some part of the earth. One could say that all rumination is worry, but not the other way around: Some worrying is not self-rumination.

(2) The article mentions that women tend to ruminate more than males—why?

The possible answer to this question is very similar to the one offered for question D5 on the (slight) superiority of females on ToM tasks. First and foremost, females’ tendency to ruminate more is statistically small—it would be inaccurate to state that females excessively ruminate and that males do not ruminate. Again, these gender differences might emerge from socialization practices, where females are reinforced when focusing on their emotions and expressing them more spontaneously compared to males. As seen in the answer to question D5, it is possible that socialization favors verbal activity in females, which in turn could mean more inner speech use; the latter has been shown to be associated with both self-reflection (Morin, 2018) and self-rumination (Nalborczyk et al., 2021)—that is, we talk to ourselves both about positive and negative self-dimensions, respectively.

It is odd that females show a small advantage over males for ToM and yet slightly self-ruminate more: Recall that self-rumination impedes ToM (question A3). No known explanations have been offered pertaining to this paradox.

(3) The paper states that private self-focus is more strongly associated with depression, whereas public self-focus is more strongly related to social anxiety. Why is that?

Private self-focus occurs when we think about non-visible, psychological self-aspects such as our thoughts, values, goals, memories, and emotions. This thinking often initiates a comparison between the real self (e.g., “I am selfish”) and the ideal self (“I would like to be generous”), which uncovers a discrepancy between the two self-representations (Carver, 1979). The admission of this discrepancy is emotionally painful and basically signifies that one is falling short on the person one wishes to be. On the long run, the accumulation of multiple discrepancies may lead to depression. Public self-focus entails thinking about visible self-aspects such as behavior, performance, and appearance. These self-aspects are open to public scrutiny, and possibly evaluation and judgment when they do not meet others’ expectations. In simple terms, public self-focus includes others’ potentially negative opinion of the self, which may cause social anxiety.

(4) Why do we experience negative affect? Should we try to eliminate unpleasant emotions altogether?

Negative affect is intrinsic to human nature and serves the very important function of signaling that something is wrong and should be addressed. Like low self-esteem (see question K4), painful emotions act as a red flag motivating self-improvement. The person who feels bad for having hurt another person’s feelings might consider making amends (e.g., expressing sorrow to the target person) in order to reduce negative affect. The person who feels distraught about an embarrassing public speech might want to practice and improve public speaking to handle the upsetting emotions. Put simply: We need negative affect to motivate change (Bernstein, 2016). Thus, trying to eliminate unpleasant emotions would be ultimately detrimental. Note that the above does not apply to clinical depression, where the patient experiences excessive negative affect unconnected to reality; in this case, suffering serves no constructive function and should be reduced as much as possible.

(5) How can we reduce self-rumination?

Clearly, there is no known universal “cure” to self-rumination (or depression for that matter): If there was one, we would all know about it and the person or group responsible for its development would be very rich indeed. Multiple websites offer questionable techniques such as identify the source of your rumination and name it, think about the worst-case scenario, and schedule a worry break—these practices will increase rather than reduce rumination!

Two main approaches show promise: Distraction and self-distancing. With distraction (e.g., reading, listening to music, sport activities), the ruminating person is encouraged not to think about troublesome self-related elements (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1993). With self-distancing (see Kross, 2022), the ruminating individual is motivated to “discuss” negative emotions as if s(he) was another person, very much like when one offers advice to a friend. Such advice is more likely to be detached and objective, rather than subjective and biased. One effective way to achieve self-distancing is via inner speech addressed to the self as “you” (“Why are you feeling that way?”) or using one’s name (“Why is John feeling that way?”), as opposed to “I”, which instead increases self-immersion (see Zell et al., 2012). Another efficient strategy is to engage in mindfulness, which comprises “decentering” (Carlson, 2013)—observing oneself from a third-person perspective and adding a distance between the self and its inner experiences (recall the answer to question B1).

1.3.9. Culture

(1) Are there cultural differences in ToM?

As a reminder, individualistic cultures (e.g., USA, Canada, UK) emphasize maintaining their independence from others by discovering and expressing their unique inner attributes, whereas collectivists cultures (e.g., Japan, Mexico, Philippines) relate more to others by attending them, fitting in, and experiencing a harmonious interdependence with them (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Before addressing the ToM question, it is worth noting that several studies have shown that brain activation during self-reflection tasks slightly differs between individualistic and collectivists participants. To illustrate, Shu and colleagues (2007) used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure brain activity when volunteers judged if personality trait adjectives described or not the self, their mother, and a public person. The medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) showed greater activation in self- than other-judgment conditions for both individualistic and collectivists participants. Interestingly, relative to other-judgments, mother-judgments activated the MPFC in collectivist but not in individualistic participants, possibly signifying that information about the mother is closely related to the self in the former. This suggests that culture modulates the psychological structure of self even at the brain level (for additional examples, see Han & Ma, 2016) and produces two different types of self-representation.

Back to ToM. One would expect collectivist cultures to show higher ToM because of their general focus on others, including their mental states, and the opposite in individualist cultures. Without being exhaustive, one study showed no striking cultural differences in frequency or quality of ToM (e.g., Grath, 2009), yet another one reported higher cognitive ToM in Iranian compared to American participants (Yaghoubi Jami et al., 2019). Thus, this remains an open question. To our knowledge, content differences in ToM (i.e., what one is thinking about when thinking about others’ mental states) have not yet been investigated, but we can speculate. Given the distinct social orientations of collectivist and individualistic cultures, we could predict that the former would engage more in cooperative ToM (e.g., “He must feel sad about this, how can I help?”) and thoughts about others’ opinion of the self pertaining to norm adherence (e.g., “I hope I did the right thing in this situation and that they think I am okay”), whereas the latter would produce more competitive ToM (e.g., “Is she going to apply to the same job position? If yes, I can I gain an advantage over her?”). Clearly, these ideas await empirical testing.

(2) Are there cultural differences in inner speech?

This question remains understudied, but in an ongoing research project, Brinthaupt and colleagues (in preparation) are compiling and summarizing results from several countries (e.g., Turkey, Korea, Japan, Poland) where inner speech was measured using the Self-Talk Scale (STS; Brinthaupt et al., 2009). The STS consists in four subscales: Self-reinforcement (e.g., “I talk to myself when I need to boost my confidence that I can do something difficult”), social assessment (e.g., “I talk to myself when I review things I’ve already said to others”), self-criticism (e.g., “I talk to myself when I feel discouraged about myself”), and self-management (e.g., “I talk to myself when I’m mentally exploring a possible course of action”).

Some general predictions are as follows. Past research suggests that collectivist cultures engage in more self-criticism compared to individualistic cultures (e.g., Heine et al., 2000; Peters & Williams, 2006). It is thus likely that collectivist groups will score significantly higher on the self-criticism subscale of the STS. Past research also shows that self-enhancement (i.e., making oneself feel better about oneself) is more common in individualistic cultures, whereas group enhancement is more prevalent in collectivistic cultures (e.g., Kurman, 2003); as well, self-promotion (i.e., highlighting one’s accomplishments) is more frequent among those with an independent rather than a collectivist focus (Ellis & Wittenbaum, 2000). We thus predict that individualistic individuals will score higher on the self-reinforcement subscale of the STS. For self-management (i.e., planning, goal setting, self-regulation), expectations are more difficult to formulate, although one could argue that both collectivist and individualist cultures equally need to engage in self-management. Thus, we foresee no significant score differences between the two cultures on the self-management subscale of the STS. Social assessment includes paying attention to the reactions of others, monitoring others, and engaging in ToM. There are good reasons to believe that collectivist groups will score higher on the self-management subscale of the STS compared to individualistic groups, given a greater concern with relationship harmony among the former compared to the latter, who report more interest with individual thoughts and feelings (e.g., Lucas et al., 2000).

(3) Are there cultural differences in self-recognition?

Yes. A general pattern is that children from collectivist cultures tend to self-recognize in front of a mirror later or not at all compared to those from individualistic cultures. To illustrate, 18- to 22-month-old Vanuatu toddlers from a small island in the South Pacific passed the mirror test at significantly lower rates compared to their Canadian counterparts (Cebioğlu & Broesch, 2021). Somewhat more striking, compared to children from the US and Canada, children from Kenyan, Fiji, Saint Lucia, Grenada, and Peru displayed an absence of spontaneous self-directed behaviors toward a mirror (Broesch et al., 2010; for experimental variations, see Ross et al., 2017). Possible explanations for these observations include the following: (a) the likelihood that for some reason, mothers from collectivist cultures may not use as many verbal prompts in front of the mirror with their kids (e.g., “Who’s there in the mirror?”) compared to mothers from individualistic groups; (b) the idea that, unlike individualistic kids, those from a collectivist background are unsure of what an acceptable response in front of a mirror may be—and therefore refrain from looking at or touching themselves. These two accounts signify that children from collectivist cultures may not fail at self-recognition per se, but rather are raised in an environment less conductive to passing the mirror test.

(4) Would someone who moved to a different culture in adulthood begin to adopt aspects of the new cultural self and loose the original one?

The person would adopt new cultural values and beliefs consistent with the new culture but would not loose his/her former cultural identity. As a matter of fact, the person could switch between the two cultural selves when moving back and forth from and to different cultural environments. This is labelled “frame switching” (Cross & Gore, 2003): We can have “multicultural selves”, we may experience multiple cultures by shifting our cultural belief systems as a function of the cultures we currently are in. Said differently, new cultural self-representations can coexist with older ones in memory.

Imagine Angelo, who was born in Canada of Filipino parents. His parents have been living in Canada for a long time and display mostly individualistic characteristics. At the age of 16, Angelo travels to the Philippines for a month to visit his grand-parents and other family members, who have been living all their lives in a collectivist environment. By the end of the month, Angelo will have adopted and exhibited typical collectivist qualities such as being family-oriented, comfortable spending time with many people in small quarters, and respect for the elderly. Angelo then flies back to Canada, and within a short period of time, switches back to his more individualistic self, and seeks privacy and personal space, focuses more on his personal goals, and analyzes what is unique about him. Angelo did not loose his individualistic traits when traveling to the Philippines—he added a new cultural identity that will remain dormant when in Canada, but which will be reactivated when he goes back to his ancestral land.

1.3.10. Self-Esteem

(1) The article states that self-esteem peaks at ages 50 to 60 and then drops—why?

Self-esteem refers to how one globally evaluates oneself (Greenwald et al., 2002). By the age of 50 to 60, most people have reach full performance at work, have developed a tight and large social network, and are still in fairly good health; these factors make them feel good about themselves, hence a relatively high self-esteem. There is individual variability of course, but past 50-60 is when most people retire, leading to less work satisfaction and income, as well as the loss of several professional relationships. This also represents a time when health issues are more likely to emerge, and when physical (e.g., vision, motor skills) and cognitive (e.g., memory) competences start to steadily decline. This is why self-esteem too declines. It is important to note that the lowering of self-esteem in older age is not drastic: It would be inaccurate to state that older people have low self-esteem; rather, self-esteem is a bit lower compared to its level a couple of decades earlier.

(2) Is self-esteem connected to personality?

Absolutely. High self-esteem is associated with higher E (extraversion), A (agreeableness), C (conscientiousness), and O (openness to experience), as well as lower N (neuroticism; anxiety) (Amirazodi & Amirazodi, 2011). Opposite patterns are observed for low self-esteem.

(3) What are some of the factors that shape self-esteem?

In essence, past and current life experiences that make a person feel good about him/herself will increase self-esteem, and vice-versa. Among these, one can list past success and failure experiences, caregivers’ patterns of reinforcement and punishment toward the child, physical appearance, self-evaluations from social comparisons, acceptance or rejection from others, and competencies (see Hewitt, 2009).

(4) What are some consequences of low self-esteem?

As seen with self-knowledge (question B4), ToM (question D2), and self-regulation (question E2), deficits in self-processes can have dramatically negative consequences, and self-esteem is no exception. These include behavioral (e.g., crime), physical (e.g., substance abuse) and mental health problems (e.g., anxiety, depression), marital and friendship conflicts, difficulties at school and work, and thus overall lower levels of life satisfaction (Kuster et al., 2013; Orth & Robins, 2014). The main reason for this is that the person who evaluates him/herself negatively will likely be ridden by self-doubts which will impede decision making, self-regulation, and performance in a wide array of life outcomes. Clearly, high self-esteem is associated with the opposite outcomes.