1. Introduction

A construction claim is defined as a compensation request for unanticipated risks which may escalate to a dispute if not agreed (Kumar et al., 2020) or settled by fulfilment of the contract provisions and detailed technical documents/ information (Gurgun and Koc, 2022). Arguably, the claim requests are rooted in reoccurring conflict (as a root cause) (Kumaraswamy, 1997) involving the contractual parties (Fitriyanti and Adly, 2022) (i.e., client, contractor and sub-contractor) (PMI, 2017). Managing such claims represent specific challenges and a heavily gated process that has been extensively researched (cf. Kululanga et al., 2001; Makarem et al., 2012; Abdul-Malak and Abdulhai, 2017). Barakat et al. (2019) developed the all-encompassing claim and dispute timeline, drawing on six widely adopted standard construction contract conditions viz. the American Institute of Architects (AIA), ConsensusDocs, Fédération Internationale Des Ingénieurs Conseils (FIDIC), Engineers Joint Contract Documents Committee (EJCDC), the New Engineering Contract (NEC) and Joint Contracts Tribunal (JCT). Mayer (2015) proposed ‘conflict engagement’ as a method for managing conflict and litigation. Considering the root cause and unanticipated risks of requests, claim management can be defined as a complex conflict engagement decision to compensate cost implication of unanticipated risks, whether at the project or organisation level.

Several factors are perceived to improve claim management at the organisational level, including: (1) considering the hard and soft categories of claims (Parchami Jalal et al., 2021); (2) directing the relationship between roles of the organisation’s various units and the claim administration (Abdul-Malak et al., 2020); (3) focusing on the internal and external context in the organisation (Martinsuo and Geraldi, 2020); (4) relying on non-immediate resolution or understanding aspects of complexity (Shenhar and Holzmann, 2017); and (5) considering distinct categories of business disputes viz.: partnership, intellectual property and patent, contractual and employment (Trinkūnienė and Trinkūnas, 2022). Notwithstanding these, Locatelli et al. (2022) states that the project manager (who sets the ‘iron triangle’ of time, cost and quality benchmarks) priorities to manage construction law professionals (e.g., claim specialists, lawyers and others) but some of whom may have other priorities and concerns. Hence, governance (of project management) has been suggested for influencing decision making of policy, strategy, tactics and operations levels on projects and in project-based organisations (Turner, 2020). Miterev et al. (2017) proposed the modified 5-dimensional model which stipulates internal fit of project-based organisations (PBOs) to design their organisations. Müller et al. (2019) introduced the onion model of organisational project management (OPM) with 22 elements in seven layers and discovered how they are integrated. Accordingly, the organisational offices of PBOs can be developed by focusing on the approach level of OPM context. This point concurs with Karim et al. (2022) who confirmed that organisational aspects and practices for improving OPM maturity.

In a PBO, the improvement of claim performance is notoriously problematic because it represents an inevitable result of paradoxes, complexities and uncertainties encountered when managing behavioural intra-firm claim decisions. The claim management office (CMO) concept contributes to managing organisational-level related claims (Parchamijalal et al., 2023); however, the claim and project performance indictors differ from each other (Seo and Kang, 2020). Due to this difference, the CMO functions must be separated from the project management office (PMO) and other organisational related units. CMO-related functions (i.e., dispute resolution and organisational ambidexterity management) have thus received specific attention in the project management discipline (cf. Echternach et al., 2021; Jagannathan and Delhi, 2022; Shalwani and Lines, 2022; Gunduz and Elsherbeny, 2020; Senaratne and Wang, 2018). Understanding the CMO-related organisational ambidexterity helps a construction company to improve its performance (cf. Duodu and Rowlinson, 2021, Hughes, 2018), particularly when managing conflicts and ambidexterity (cf. Midler et al., 2019; Wang and Wu, 2020). However, the performance dimensions and indicators with CMO-related levels and its intra-firm structure is yet to be fully understood. Some researchers (cf. Anago, 2022; Petro et al., 2019) proffer that integrating organisational ambidexterity theory with X-inefficiency theory is relevant, resulting in more qualitative insights into intra-firms' behavioural dynamics. An unanswered question however, is how do PBOs design an OPM-based CMO approach for improving industry-related claim performance? A reference framework for understanding CMO structure and components (and inquiring its impact on claim performance based on the organisational ambidexterity and X-inefficiency theories) therefore remains wanting. This demonstrates a lacuna in the body of knowledge on implementing CMO within PBOs, particularly in large construction firms.

Against this contextual backdrop, this work integrates an organisational ambidexterity with X-inefficiency theory, generating a reference framework for CMO by probing its implementation in a large international construction firm. Concomitant objectives are to: 1) adopt the CMO functions and their subfunctions; 2) probe internal multilevel fit within PBOs for rational decisions when implementing CMOs; and 3) explore the claim performance indicators of PBOs for improvement. This reference framework will assist construction companies in devising plans for early management of their claims to improve claim performance, particularly claims related to global industry concerns. Further, the framework can be used for participants of wider industries when considering their claims. This study makes contributions to both research and practice by garnering true insight into the CMO concept, setting a solid reference for formulation of hypothesis and developing a practical roadmap for future work.

2. New OPM-based CMO approach for wide industry-related claims

Since the CMO is an under-theorised concept within the approach level of OPM, it is less common in project and organisational studies of PBOs. However, the different levels of the CMO maturity model are well documented (Parchamijalal et al., 2023). Thus, to set the context for this present research in the wider body of knowledge, particular attention is given to: (1) problems of managing built environment claims; and (2) theoretical foundations of CMO within PBOs. Based upon this synthesis of CMO-related literature, new basic CMO knowledge development within PBOs is generated.

2.1. Problems of managing project-based organizational claims

A claim request is rooted in triggering events of risk and conflict. Kumar et al. (2020) suggest that if the cost implications of unanticipated risks are not considered and agreed, claims formation and disputes occur. However, drawing on: the industrial classification of construction businesses (cf. Ye et al., 2018); reframing construction within the built environment (De Valence, 2019); and the project and inter- and intra-organisational communication (Seo et al., 2021), such claims are complex and diverse. This is because (apart from construction companies) many firms from other industries may be involved in other services provided to the build environment sector’s supply chain (Ive and Gruneberg, 2000). Considering the industrial diversity of construction businesses, in particular international construction and entry mode, highlights the need to pay more attention to service-oriented built environment context with specific managerial process. (cf. De Valence, 2019; Kumar Viswanathan and Neeraj Jha, 2020; Obi et al., 2020; Martek, 2022). Arguably, Alsamarraie and Ghazali (2022) concluded that cost overruns, schedule delays and erratic project performance are common triggering events of any organisation, some of which may lead to claims in such PBOs.

Numerous studies (cf. Chau, 2007; Tanand and Anumba, 2010; Guévremont and Hammad, 2018 Hadi, 2018; Ali et al., 2020; Nafe Assafi et al., 2022) have suggested feasible alternatives to performing a claim management process viz. artificial intelligence, software or online internet capabilities. Such alternatives however, typically encounter inherent problems. For example, framework constraints provided by building information modelling (BIM) include: the inherent complexity of a contract; different conditions of each contract; the necessity to use integrated project delivery (IPD) as a project implementation system; and a manual modification of the values due to the design change (cf. Charehzehi, 2017; Shahhosseini and Hajarolasvadi, 2018; Ali et al., 2020). The dark side of projects accompanied with organisations' concerns (cf. Enshassi et al., 2009; Bakhary, 2015; Locatelli et al., 2022;) (in particular, the project claim management committee with no client focused of PBOs and their non-project works (cf. Henning, and Wald, 2019; Dang et al., 2020; Parchamijalal et al., 2023)), can be also considered as other problems in managing built environment claims. Notwithstanding these, Parchamijalal et al. (2023) suggested CMO as a solution for implementing process management to control, reduce and improve a construction organisation’s claims performance using five-pronged maturity levels viz.: preliminary, awareness, standard, integrated and advanced. However, the functions, intra-organisational fit and its claim performance indicators remain undefined. By doing just these, a CMO can be used for managing the broad construction (as a built environment sector) claims, rather than focusing on narrow construction. According to Müller et al. (2019), the program and organisational office components are related to the organisational integration and OPM approach layers, respectively. Rijke et al. (2014) believed that program management constitutes a more strategic focus rather than project management, drawing on its effective/timely decision making and competences (Miterev et al., 2016; Trzeciak et al., 2022). Shao et al. (2012) pointed that the program context has two dimensions of types and characteristics, which the organisation’s claims can be effectively managed under such programs. Gebken and Gibson (2006) put disputed claims indictors into two categories; frequency indicator (i.e., company history and market environment) and severity indicators (i.e., direct, indirect and hidden costs). Seo and Kang (2020) also proposed three frequency performance indicators of claim management: entitlement miss, time-bar miss and lack of substantiation. Notably, as the company history and market environment are among the claim performance indicators, expanding the necessity for managing organisational ambidexterity will improve company performance.

Previous scholars (cf. Hughes, 2018; Duodu and Rowlinson, 2021) concluded that organisational ambidexterity, as an organisation- and management-focused theory, may effect operational and financial dimensions of firm performance. The concept of organisational ambidexterity consists of (Petro et al., 2019): levels (strategic, projects, organization and individual); dimensions (knowledge, technology, behaviour and process); and mechanisms (structural, learning, selection and communication). Although international construction company cases contribute to understanding the diversification of construction businesses (cf. Ye et al., 2018; Martek, 2022), it is imperative to use relevant theories for generating a knowledge base of CMO.

2.2. Theories foundations of CMO within project-based organizations

Wu et al. (2019) place indicators of project performance into five categories viz.: 1) the project’s overall performance (i.e., time, cost and quality); 2) the project’s multiple goals (i.e., claim management); 3) stakeholders’ satisfaction (i.e., client, contractor and subcontractor); 4) potential future collaboration; and 5) capability enhancement. Similarly, Gunduz and Elsherbeny (2020) highlighted claim management is among measures of core competency function, as the main functions of contract administration performance framework. Therefore, claim management is a core competency for managing construction claims, with its specialised indicators and two levels of project and organisation. Such levels are echoed by several researchers (cf. Tochaiwat and Chovichien, 2004; Baatez; 2008; Stamatiou et al., 2019) who use five processes of claim management (i.e., identification, notification, documentation, presentation and resolution). Duodu and Rowlinson (2021) claimed that the operational and financial dimensions of firm performance affected by the organisational ambidexterity is among the most important theories and constructs which are organisation- and management-focused (Hughes, 2018). The concept of organisational ambidexterity includes (Petro et al., 2019): levels (i.e., strategic, projects, organisation and individual); dimensions (i.e., knowledge, technology, behaviour and process); and mechanisms (i.e., structural, learning, selection and communication).

Recently, organisational ambidexterity and X-inefficiency theories have gained some traction as a theoretical foundation to explain intra-firm related phenomenon (cf. Mirzaee et al., 2022; Anago, 2022; Wilms et al., 2019; Tamayo-Torres et al., 2017). This present study attempts to integrate X-inefficiency theory with organisational ambidexterity theory, as a plausible choice to facilitate the declaration of improving organisational claim performance. This is because the X-inefficiency theory focuses upon the utilisation inefficiency of firm’s sub-optimally claim performance (Leibenstein, 1979; Vanagunas, 1989), whilst simultaneously managing the exploration -and exploitation-related problems (O'Reilly III, 2013; March, 1991). Notably, integrating organisational ambidexterity (i.e., the organisation behaviour and selection levels) with the behavioural dynamics of X-inefficiency theory (i.e., quality decision-making), helps uncover CMOs’ functions for improving claim performance. These functions are managing closeout completion claims, ambidextrous program management and dispute settlement (e.g., alternative dispute resolution, litigation and ambidexterity management). ‘Closeout’ management, as a main element of the contract administration performance framework, can engender optimal performance (Gunduz and Elsherbeny, 2020). However, managing its completion claim is complex and involves: 1) considering the rejected requests of project issue management. Shalwani and Lines (2022) proffer that issue management (as a project control technique) for mitigating of the project challenges, by using the issue log during execution for the remainder of the project; and 2) considering organisational project/ program management (cf. Havila et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2021). In addition, some scholars (cf. Jones et al., 2019; Matthews et al., 2015) claim that process improvement of organisational ambidexterity is critical to understanding its conflicting aims and contradictory variations. 'Ambidextrous program management' (as a new type of multi-project management), bridges the project management and ambidexterity literature (Midler et al., 2019).

To effectively manage program conflicts, Wang and Wu (2020) suggest the program conflict management model (PCMM) including conflict identification, prevention, resolution and feedback, with unique causes, impacts and alternative resolution strategies. Nevertheless, disagreement abounds among researchers about dispute-related issues. For instance, some researchers (cf. Fenn et al., 1997; Gebken and Gibson, 2006) believe that: conflict and dispute are two separate phenomena and that conflict cannot be avoided but instead should be managed and minimised. Hence, where conflicts lead to disputes, they should be resolved. In contrast, other researchers (cf. Acharya et al., 2006; Osei-Kyei et al., 2019) believe that conflict itself should be resolved and that a spectrum of conflicts can occur and culminate (or intensify) into disputes. Notwithstanding these, when a dispute emerges, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) methods are commonly adopted. ADRs (representing non-binding negotiation to binding arbitration) are alternatives to avoiding litigation in disputes among contracting parties (cf. Lee et al. 2016). Haugen et al. (2015) split dispute resolution strategies into two dichotomous categories viz.: non-adjudicative (including negotiation, partnering, consulting and mediation); and adjudicative (such as arbitration and litigation). Surprisingly, Chaphalkar and Sandbhor (2015) believe that although ADR methods seek to avoid litigation, their implementation creates conflicts in defining the procedure and resource required. Although the non-fulfilment of resolution clauses is among the major causes of litigation (Sinha and Jha, 2020), there are some focus areas, people and behavioural factors and process which decode a decision to pursue litigation (DTL) and facilitate its management (cf. Echternach et al., 2021; Jagannathan and Delhi, 2022; Jagannathan, Delhi, 2020).

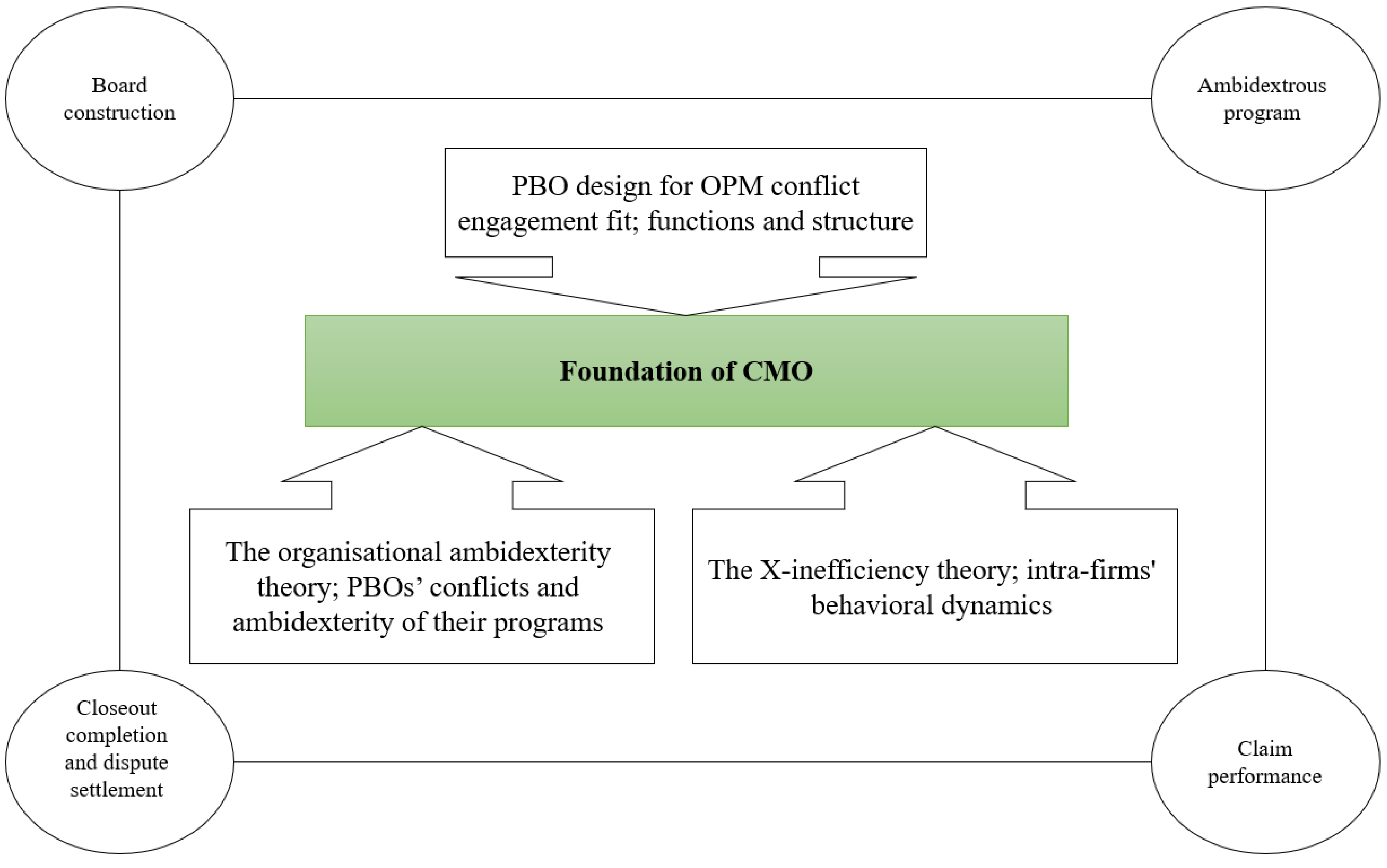

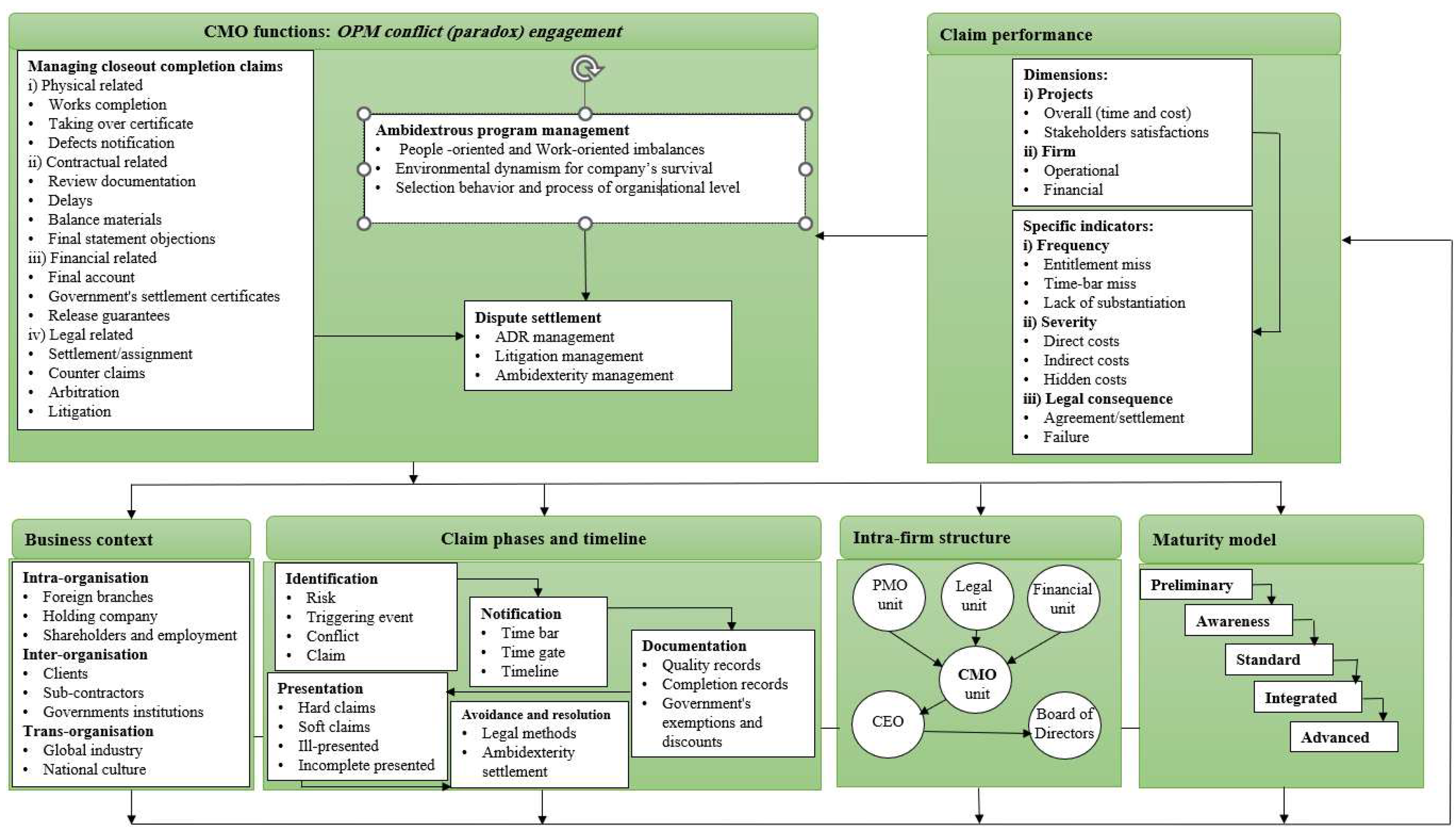

Consequently, based upon the literature and contributing towards organisational ambidexterity and X-inefficiency theories – in a construction context, basic CMO knowledge development is uncovered (refer to

Figure 1). Thus, adopting a CMO foundation among the three main components of: 1) PBO design for OPM conflict engagement fit (functions and structure); 2) the organisational ambidexterity theory (PBOs’ conflicts and ambidexterity of their programs); and 3) the X-inefficiency theory (intra-firms' behavioural dynamics) - this present study therefore proposes a CMO foundation that utilises these three components and other PBOs' construction claims components (see

Figure 1). Consequently, drawing on this foundation and using an international construction firm case, this work endeavours to develop a reference framework for a CMO.

3. Research methodology

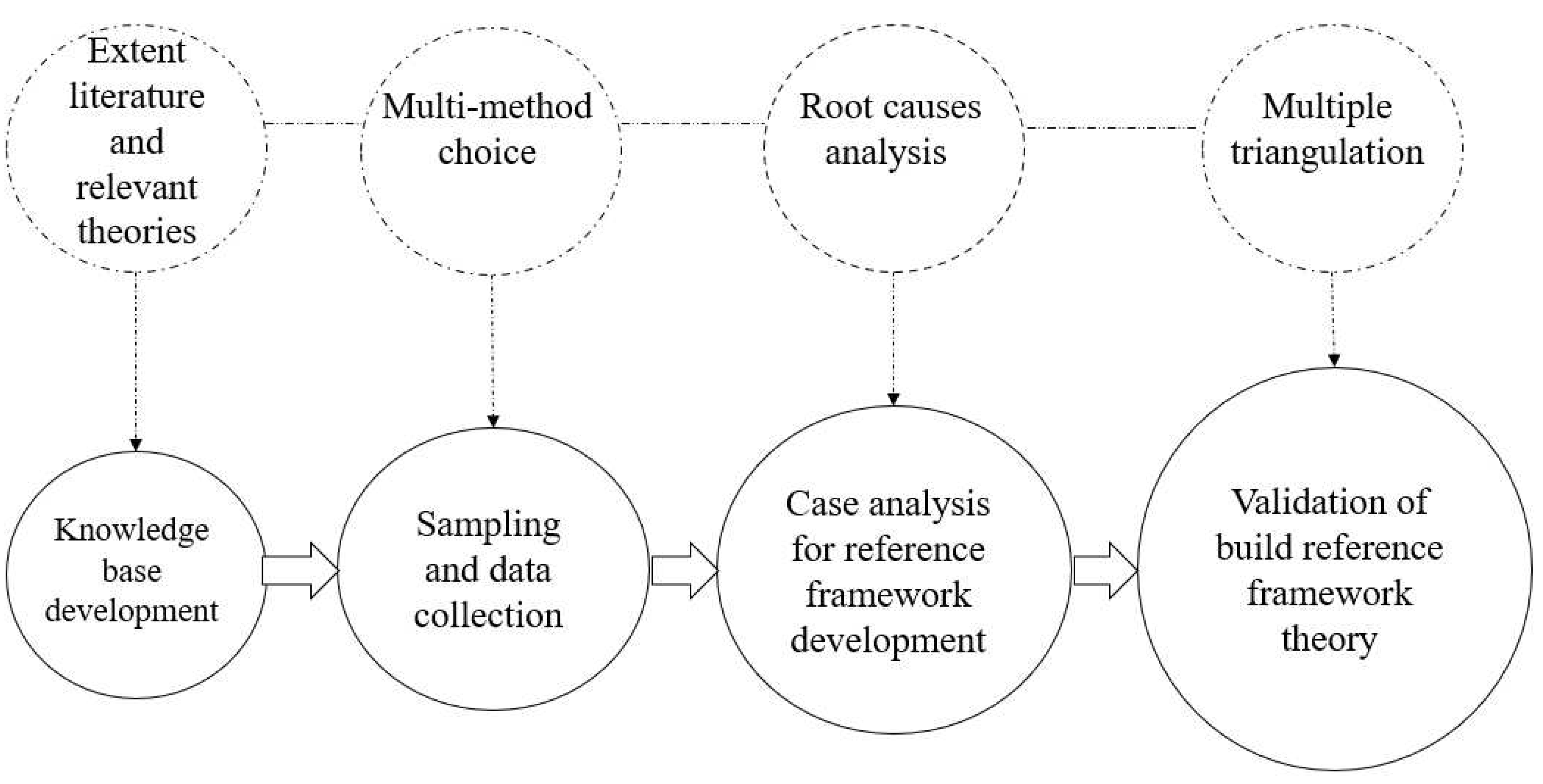

Underpinning philosophies adopted within this present study are interpretivism and postpositivism (cf. Bortey et al., 2022; Roberts and Edwards, 2022; Bayramova et al., 2023) to test theories proposed using abductive reasoning. Specifically, the research process adopted consists of four main steps: 1) identifying knowledge base elements of CMO (see

Figure 1), 2) sampling and data collection, 3) data analysis (root causes analysis); 4) multiple triangulation-based validation – refer to

Figure 2. The research undertaken was governed by a strict ethical protocol guiding this work that included: anonymising all participants’ demographic details; holding all information in a secure location and neither disseminating or divulging to any third party without their express permission in writing; and ensuring all participants could access results in aggregate form post research completion (cf. Fisher et al., 2018; Law et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2022)

3.1. Sampling and data collection

Integrating an extensive review of extant literature and relevant theories resulted in the development of a knowledge base for CMOs (see

Figure 1). A multi-method approach, including a single case study and an expert panel, was used for sampling and primary data collection. This approach is chosen because of its suitability for understanding complex and unique qualitative elements of a construction related phenomenon (cf. Lehtovaara et al., 2022). Consequently, a case study strategy (cf. Fulcher et al., 2022; Owusu-Manu et al., 2022) is used for addressing knowledge deficit on the specific problems of ambiguous intra-firm related phenomenon and context. It should be noted that managing the sub-optimally and exploration -and exploitation-related problems of PBOs are ambiguous, owing to their inefficiency behavioural dynamics and organisational ambidexterity paradoxes, respectively. To this effect, a single case study focuses on phenomenon and context boundaries to clearly comprehend the dynamics existing within a single real-life context setting (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 2009). Moreover, to achieve a good outcome from a case study, in addition to its archival documents, the voice of its participants must be included. By doing so, the mid- and top-level managers views of an international construction company were sought, by forming a focus group discussion (FGD), consisting of: Chairman of the Board, Director of CMO Department, Director of PMO Department, Director of Legal Department and Director of Financial Department. FGD is a dynamic and widely adopted qualitive method; for this present research it involves a group comprised of 5 – 10 participants which is facilitated by a mediator (the researcher) to add dimensions of interactions among them (Kitzinger, 1994; Aladag and Işik, 2017). FGD also considered a majority view to resolve any disagreements between participants. Previous research work (cf. Mirzaee

et al. 2022a) adopted a case study and its internal FGD for developing strategies in board related construction. Thus, a multi-method approach has been used to discover the efficiency of adopting CMO in construction companies, to develop a reference framework.

3.1.1. Selection criteria

As an international firm with experience of Iranian domestic and international construction, Company B was selected for the case study and its intra-organisational structure in managing claims was reviewed based on the following criteria. First, managing international construction business requires comprehending the sector players (including the involved case firms (as a provider of projects)) and their countries (of primary location (e.g. headquarters) and operation) (cf. Martek, 2022; Fletcher et al., 2018). In this regard, Company B of Iran has involved to build international projects in Iraq. Second, Company B has encountered extrinsic macro-economic risks in domestic and international dimensions. It is because an international construction company comprises diverse’ risks and requires managerial best practice (Lee et al., 2011). Third, Company B established a department for managing claims at the organisational level. Notably, the designed organisational structure for this department has fundamental differences with the PMO and legal departments, especially in terms of goals, strategies and organisational tasks. This point was echoed by Parchamijalal et al. (2023) who noted that the CMO maturity model contributes to managing such claims. Finally, in shedding light on the “selecting suitable case,” particularly in the period of time available for the case and its internal FGD, this international firm case can optimise organisational learning (Tellis, 1997).

3.1.2. Case and its participants description

Company B has a registered head office in Tehran and is a “first-grade” large (and general) contractor in six industrial fields of: buildings and structures; water; power; industry and mining; facilities and equipment; and roads and transportation. Established in the 1992, company B has participated in 51 large national projects and five international projects – with a variety of project delivery systems such as: engineering, procurement, construction (EPC); build, operation, transfer (BOT); and design, build, financing (DBF). Company B is also registered at four overseas “branch offices” and a “holding company” with five subsidiaries – in design, trade, machinery, steel works and insurance services. Company B’s man-power is divided into three main parts viz.: staff (388 members); onshore (around 4,000 members); and five main subcontractors. The company has had a five-year period (2011 to 2015) turnover of 216, 117, 129, 139 and 154 million dollars, respectively. Projects competed since establishment include: 54 Km of underground tunnel and metro lines; 7,500 MW (15 cooling towers) of power plants; construction of a 15,000 tons/day cement factory, 1.12 miles of bridges built; 700,000 M2 building of building space; 600,000,000-litre fuel tankers; 147,500 seats stadium; 5,310 vehicle multi-story parking; and 600 hospital beds. In 2021, a new department created in company B named “projects closing and follow-up” was establsihed for managing organisation claims as a bespoke team with functions that differ from the contract’s affairs office and PMO. All members of the FGD – with 20 to 35 years of management experience – hold main managerial positions within company B, who were somehow involved in settling the organisation’s disputed claims. Considering these, the B company and its internal FGD participants description meet the sample eligibility criterion for inclusion in this present research.

3.2. Data analysis

Data analysis techniques adopted follows a root-cause analysis process (cf. Liu et al., 2015; Maemura et al., 2018; Mirzaee 2022b). Accordingly, based on the CMO foundations diagram (

Figure 1), root causes and organisational claim performance in company B was identified. Further, the FGD-based case analyses (derived from

Figure 1) were discussed to developing a reference framework for CMOs, to improving claim performance of PBOs.

3.3. Multiple triangulation-based validation

Akin to previous studies (cf. Aladağ and Işik, 2017; Mirzaee et al., 2022a), a

‘multiple triangulation’ approach is used for validating the framework, by developing a FGD and the case data (see

Figure 2). According to Kimchi

et al. (1991), multiple triangulations can be fulfilled by developing an investigation triangulation and a data triangulation simultaneously. Notably, for avoiding human bias and more confidence, the views of a new (external) FGD (a senior expert panel with higher experience than the internal FGD) are taken to fulfilling the validity.

4. Root cause analysis: the multi-method results

Notable claim performance observed in company B were government related penalties, actual ending deviation and abounding of some projects, bank guaranties tensions, dissatisfied clients and seven of under legal (in the stage of arbitration or judicial proceedings) projects and market development issues– particularly, in terms of domestic construction. These negative outcomes stemmed from entitlement miss and time-bar miss when handling its projects claims, and ignoring its financial and operational dimensions. Although the “

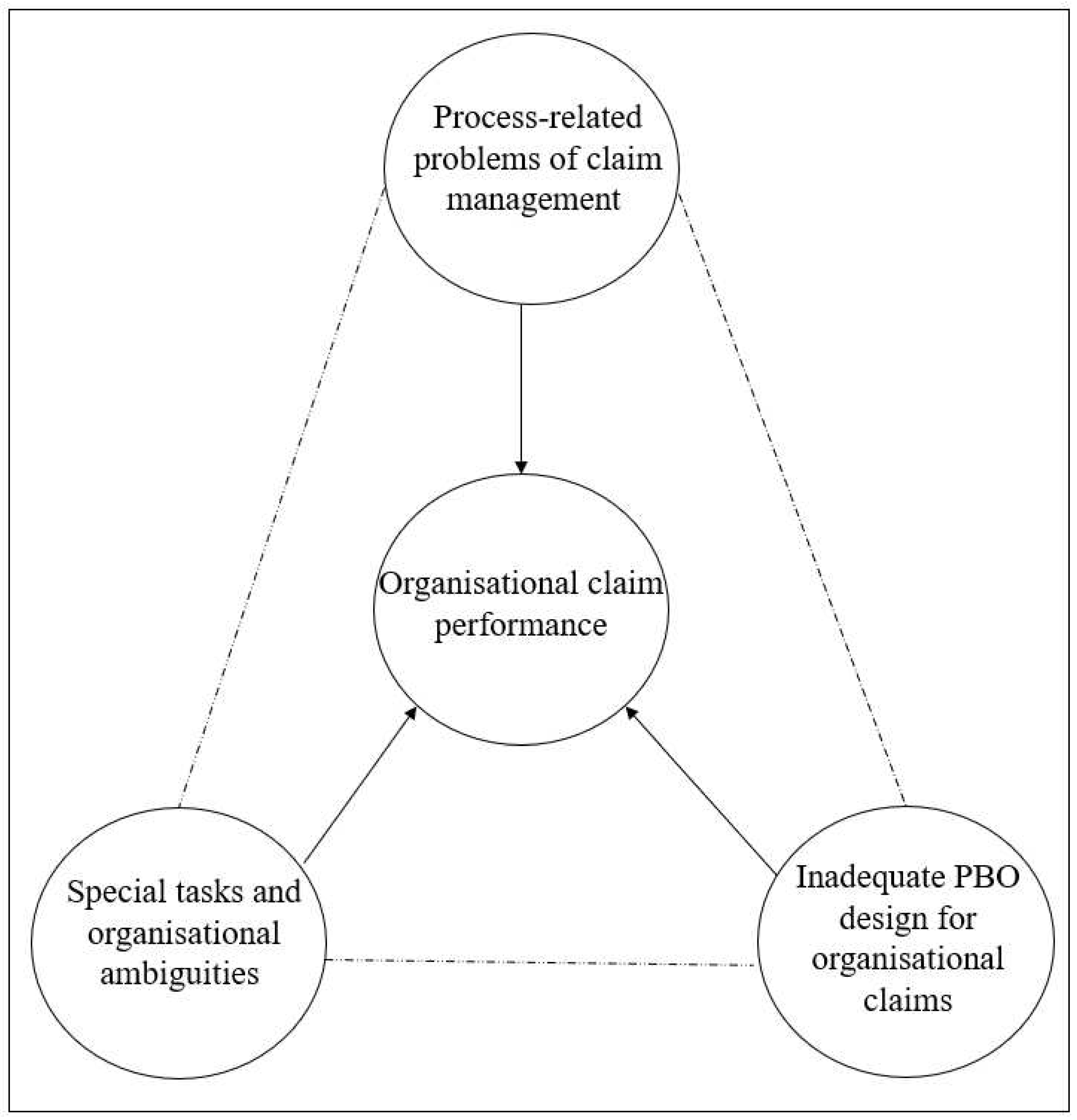

projects closing and follow-up” was developed for managing such claims, company B has encountered several disputed claims (e.g., lack of substantiation) and severity indicators (e.g., direct cost of litigated cases). The causality diagram of knowledge depicts and claim performance of company B (refer to

Figure 3), suggested by the internal FGD and shedding light on extant literature and relevant theories of the CMO foundations. This diagram consists of three root causes: 1) special tasks and organisational ambiguities; 2) process-related problems of claim management; and 3) inadequate PBO design for organisational claims and its solution. More depth, precision and validation details are clarified in the following sub-sections.

4.1. Special tasks and organizational ambiguities

The scope of managing projects claims within company B, according to the archival documents (refer to

Table 1), was divided into ongoing and closing categories with special tasks.

Although managing the issues and claims (in both the projects and company B’s organisation levels) can be achieved comprehensively under these categories, the “projects closing and follow-up” was faced with some organisational ambiguities, namely: 1) overlapping with other departments. The claim performance indicators have been neglected, as the time and cost deviations are related to the PMO’s monitoring function. The balance of materials and contract status reports, and staff complaints are also related to the contract’s affairs and legal departments, respectively; 2) boundary between the issue and claim management. It is because issue management (as a promising project control toll), deals with project’s matters which their request’s forms were agreed between contracting parties previously. Notably, such matters can be settled by claim management when the issues remain dissolved. However, the “performing other tasks assigned by the senior managers of the organization” has not been related to project claim management due to its organisational nature; 3) managing organisational ambidexterity. This encompasses paradoxical decisions for the chief executive officer (CEO) of company B, particularly in the people-oriented and work-oriented imbalances and environmental dynamism for the company’s survival. Some members of the FGD believed that the CEO is more work-oriented rather than being economic-oriented, shedding light on the continuous discussion among them – the economic-oriented replaced with people-oriented. They concluded that work and economy are intertwined and inseparable categories, and an influencing factor of people is emotion (i.e., emotional intelligence) due to its closely coupled relationship with conflict. However, all the members agreed the continuity of work harmonisation may effect on entire projects’ economic viability; and 4) dispute resolution as a specific function of the department. The FGD accepted that the ‘managing completion closeout claims’ can be considered as a specific function for the CMO, which it may complete with the dispute settlement. It is because actual ending deviation and abandoning of some projects were the main problems of company B thus, optimal closing of these problematic projects was a priority for handling. To this effect, the concept of managing ambidextrous programs were considered by the department. However, such closing of projects resulted into organisational paradox conflicts, some of which required the ADR and litigation method. Besides, managing ambidexterity in some cases accompanied by adopting effective dispute settlement methods overlooked in company B.

4.2. Process-related problems of claim management

In the “

projects closing and follow-up” department, different processes were involved in different groups’ levels with multi-levels within each group: 1)

claim phases and timeline. Documentation (i.e., quality and completion records) and presentation (i.e., ill-presented and soft claims) were the main concerns when managing organisational claims. The FGD disclosed that in some projects the shop and/or as built drawings were not submitted for arbitrators, which was a root cause for their unfair decision when the votes are announced. Arbitrators also encountered some limitations (such as delayed payment, tax and insurance penalties) because of poor statement of claims and legal remedies for soft claims. 2)

maturity model. This model within company B was identified under preliminary claim management, due to a lack of clear planning towards claims, and its transition stage was based on organisation awareness claim management. However, the FGD claimed that by supporting the board of directors and CEO, the claim submission strategy should be promoted. To this effect, the financial resource and authority were the main problems to implementing this strategy, since these are prerequisites for upgrading the level of maturity even to the advanced level.

3) business context. The internal FGD within company B highlighted the crucial role of business context process, as some of which operated outside the international (not domestic) market. Drawing on how the company claims can be comprehensively identified, the business levels were intra-organisation (four foreign branches and a holding company with five subsidiaries), inter-organisation (clients, sub-contractors and governments institutions) and trans-organisation (global construction and national culture) levels. According to the FGD, these multi-levels process were identified as the potential process in a broad construction perspective, in particular, international entry mode. 4)

intra-firm structure. Some functions of the “projects closing and follow-up” implemented through coordination with other internal departments (see

Table 1) e.g., contract affaires, PMO, financial and legal offices. Although outputs of such offices in claim-related issues was finalised by the “projects closing and follow-up” office, the FGD prescribed an insightful understanding of the PBO design framework to facilitate rational decision making.

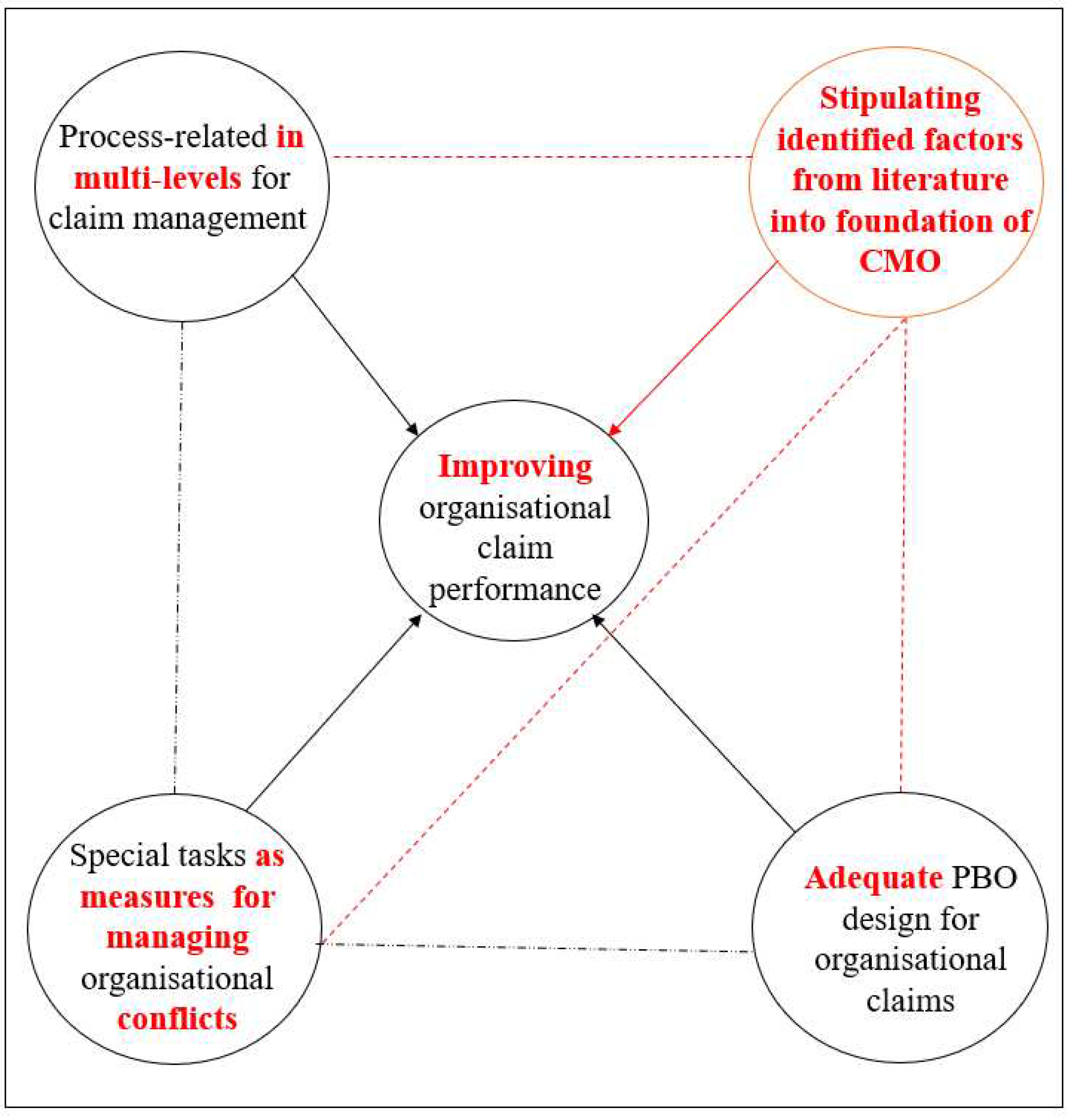

4.3. Inadequate PBO design for organizational claims and its solution

Although structure and process were considered as the main aspects in PBO design of company B, the FGD members suggested that the strategy, behaviour and human resource aspects also should be considered for achieving a fit design. As a first stage towards providing a solution,

Figure 4 outlines the FGD’s comments for improving the root causes of claim performance in company B, drawing on its causality diagram (see

Figure 3). To address these commitments, as a refined and final stage, the reference framework for claim management office (RFCMO) is presented in

Figure 5. The developed basic knowledge, causality diagram and initial solution outlined for CMO, intertwined with its functions, processes and claim performance dimensions/indicators are the basic components of the framework.

4.3.1. Validation of the framework as build theory

The case study (with its internal FGD) reaffirms the framework’s validity, as a data triangulation element of the multiple triangulation approach. In this regard, for validating of the reference framework, all of the basic components (including the knowledge base, causality diagram and primary framework) were considered by an external FGD from four high-ranking national organisations including: 1) two of the three members of the Supreme Technical Council of Iran’s Construction Industry, which deal with arbitration of disputed infrastructure projects; 2) the CEO of the construction companies syndicate of Iran, which deal with all contractors affairs; 3) a board member of Iran Technical and Engineering Service Exporters Association, which deal with international firms issues; and 4) the CEO of a large Iranian construction company with more than 35 years managerial experience.

Regarding the stages of development of this senior specialist panel; at first, the CEO of company B was requested to recommend panel members, and then to obtain their final informed consent by following up. The CEO of company B has accrued significant managerial experience in all of the four mentioned organisations, and is still an active and well-known member of them – hence their input was invaluable. Experts’ feedback received suggested minor improvements in the CMO context and generality of the framework as follows: 1) adopting CMO for managing projects and ‘guild’ (or contracting guild/or union) claims of PBOs. That is, the project claims are specific for a project managed by the company, but the guild claims are general for all contractors (i.e., insurance and tax issues); 2) as the framework contributes to international large companies, it should be customised for SMEs; and 3) claim performance also may be affected by emotional conflict among the claim team thus, cumulative emotional intelligence within the team should be fulfilled in the maturity model of the framework (as a required resource when upgrading to higher levels of the maturity model). Notwithstanding these, this FGD fully affirmed the consistency and comprehensiveness of the framework and its inputs. Thus, taking advantage of this investigation triangulation and the data triangulation provided valuable and validated the RFCMO for managing project and guild claims of a large contractor.

5. Discussion and contributions

RFCMO is based on integrating ambidexterity theories with X-inefficiency and the case study, generating a reference framework for adopting CMO. As demonstrated in

Figure 5, the suggested framework encompasses comprehensive areas of the CMO concept. The RFCMO has six main parts, namely: 1) CMO functions; 2) claim phases and timeline; 3) maturity model; 4) intra-firm structure; 5) business context; and 6) claim performance outcomes that tailors theories, strategies and lessons learned for improvement of claim performance. The RFCMO (refer to

Figure 5) suggests that the functions (as main responsibilities) of the CMO manager include:

‘managing closeout completion claims’,

‘ambidextrous program management’ and

‘dispute settlement’. Each of them was subsequently distinctly classified into several sub-functions. Namely, sub-functions of the managing closeout completion claims are: physical related (i.e., works completion); contractual related (i.e., delays); financial related (i.e., release guarantees); and legal related (i.e., counter claims). Such organisational sub-functions, in addition to the program-related requirements, should be implemented; where some of the contract issues may not be impossible to manage by a project team. The sub-functions of the ambidextrous program management are: economic-centric and obligation-centric imbalances; environmental dynamism for company’s survival; and selection behaviour and process of the organisational level. In this part, such paradoxes can be resulted in better (constructive) task and process conflicts instead of destructive relationship conflict –as a method for managing organisational claims of firms. This point echoed by Mayer (2015) as the conflict dialectic; better paradoxes bring better conflict. The ADR, litigation and ambidexterity management are also identified as the sub-functions of dispute resolution. Hence, a CMO manger should focus on the sub

-functions of the other two parts, where some of the contractual issues and/or firm’s paradoxes may result in destructive conflicts. Notably, the reference framework (refer to

Figure 5) provides three main functions, along with 20 sub-functions, which can be used systematically by firms considering the multiple level’s groups. Moreover, some of the parts in

Figure 5, remain true to previous studies concluded viz.: 1) closeout claims (cf. Gunduz and Elsherbeny, 2020); 2) improvement of organisational ambidexterity (cf. Wang and Wu, 2020; Midler et al., 2019; Petro et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2019; Matthews et al., 2015); 3) dispute settlement (cf. Echternach et al., 2021; Jagannathan, Delhi, 2020; Lee et al., 2016; Chaphalkar and Sandbhor, 2015 ); 4) claim phases and timeline (cf. Baatez, 2008; Barakat et al., 2019; Stamatiou et al., 2019); 5) CMO maturity level (cf. Parchamijalal et al., 2023); and 6) claim performance indicators (cf. Gebken and Gibson, 2006; Seo and Kang, 2020 ). However, as previous scholars have reported on OPM-related decisions (cf. Karim et al., 2022; Turner, 2020; Müller et al., 2019), past research has not figured out how all of these behavioural-based concepts can be integrated, to the design structure of CMO in firms’ organisations. That is, the X-inefficiency and ambidexterity theories-based framework contributes to addressing the ambiguous intra-firm related phenomenon. Accordingly, 24 sub-levels under 13 levels, when undertaken in an intra-firm structure with five elements, facilitate the intra-firm decision and behaviour necessary to improve frequency, severity and legal consequence indicators of claim performance.

5.1. Contributions to theory

This study’s principal contribution is that integrated X-inefficiency and ambidexterity theories (which captures the intra-firm irrational managerial decisions, particularly in international firms) can improve claim performance. Specifically, this research contributes to current CMO literature by developing the reference framework. That is, previous research focused on how to design maturity model to effectively claim management process, ignoring the CMO functions and its specific performance indicators. This study extends the CMO literature by exploring the reference framework, which have not yet been investigated in a OPM context. Hence, this study tailors theories, strategies and lessons learned to understand how claims performance of firms can be improved. By doing this, the RFCMO establishes a solid foundation and a road map for future empirical research in CMO context.

5.2. Practical implications

This work offers significant implications for five groups of PBOs managers and teams including top managers, program managers, project managers, claim managers and claim teams. The developed knowledge base, causality and primary solution diagrams (as presented in

Figure 1,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), will inform these five groups of international construction firms to choose a CMO approach for managing OPM-based conflicts. These diagrams act as guidelines to motivate top managers of large construction firms, for rational claim decisions, shedding light on the RFCMO (see

Figure 5). The proposed framework can help the project and program managers gain a true understanding of claim performance, accompanied with its four dimensions and six specific indicators, to clarify the dark side of project management and ambidextrous programs. According to the reference framework, the claim managers and teams of PBOs are involved in three main groups of practices (at six parts)—function-, process- and performance-based activities—all of which are crucial for improving claim performance. While these practices are specific to international large construction firms within construction industry, a large international construction firm serves as a recognised proxy of broad construction, and thus can be considered to provide lessons broadly across the PBOs of other industries.

6. Conclusions

This study develops an OPM-based RFCMO for PBOs to improve their claim performance. For this purpose, ambidexterity theory was integrated with X-inefficiency theory, and the multi-methods of an international construction firm applied, as the theory building based of RFCMO. Emergent research findings reveal that the suggested framework includes ‘managing closeout completion claims’, ‘ambidextrous program management’ and ‘dispute settlement’ along with 20 sub-functions. To implement CMOs with optimal claim performance within PBOs, five group levels with 24 sub-levels under 13 levels proposed by improving the four dimensions and six specific indicators of claim performance. That is, it facilitates rational intra-firm decisions to improve claim performance by the function-, process- and performance-based activities. Further, a new perspective at six parts enables managers to determine how to design an organisational structure for adopting an OPM-based CMO in their PBOs, particularly in international construction firms. This would enable them to clarify the dark side of project management/ ambidextrous programs thus helping them to make rational claim decisions.

There are some limitations associated with this research. First, as the managing closeout completion claims are project-and program-based, the research findings require future projects and program case studies. This is because ‘program closeout’ may improve firms’ claim performance and has specific indicators. Second, as the FGD noted the current level of the CMO maturity model can be promoted by equipping financial and team emotional intelligence resources. Third, Wang and Wu (2020) developed a program conflict management model with specific elements, some of which are under the CMO functions. In this regard, the ‘program conflict (paradox) engagement’ aspects remain unknown. Fourth, the FGD highlighted findings contributes to specific large contractor firms, other contractor firm types (i.e., SMEs) may need some changes in the framework. The CMO structure also shows the consensus on the effectiveness of contractors’ firms. Considering these, the clients, consultants and construction law firms, in addition to the other types of contractor firms will need additional case studies. Further, the average practitioner may be unfamiliar with the scientific instruments adopted in the framework. Hence, future work is required to develop a graphical user interface (GUI) front end and relational database backend to create user friendly software that enables practitioners use the developed framework and predict the risk level posed in practice. However, the framework could be performed for other (types of contractors) firms and industries to boost PBOs managers into improving claim performance. By using the RFCMO and appointing the director of CMO, they will also enable to select a specialist dispute review board or arbitrator(s), as conflict specialist, when PBOs want to settle their disputes professionally and efficiently.

References

- Abdul-Malak, M.A.U.; Abdulhai, T.A. Conceptualization of the contractor’s project management group dynamics in claims initiation and documentation evolution. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction 2017, 9, 04517014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Malak, M.A.U.; Srour, A.H.; Demachkieh, F.S. Decision-making governance platforms for the progression of construction claims and disputes. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction 2020, 12, 04520025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, N.K.; Dai Lee, Y.; Man Im, H. Conflicting factors in construction projects: Korean perspective. Engineering, construction and architectural management 2006, 13, 543–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladağ, H. and Işik, Z. Role of financial risks in BOT megatransportation projects in developing countries. Journal of Management in Engineering 2017, 33, 04017007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B. , Zahoor, H. , Nasir, A.R., Maqsoom, A., Khan, R.W.A. and Mazher, K.M. “BIM-based claims management system: A centralized information repository for extension of time claims.” Automation in Construction, 2020, 110, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsamarraie, M.M.; Ghazali, F. Evaluation of organizational procurement performance for public construction projects: Systematic review. International Journal of Construction Management 2022, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anago, J.C. How do adoption choices influence public private partnership outcomes? Lessons from Spain and Portugal transport infrastructure. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 2022, 15, 469–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baatz, N. Problem management/dispute resolution in partnering contracts. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Management, Procurement and Law, 2008, 161, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhary, N.A.; Adnan, H.; Ibrahim, A. A study of construction claim management problems in Malaysia. Procedia economics and finance 2015, 23, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, M.; Abdul-Malak, M.A.; Khoury, H. Sequencing and operational variations of standard claim and dispute resolution mechanisms. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction 2019, 11, 04519012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayramova, A., Edwards, D.J., Roberts, C. and Rillie, I. Enhanced safety in complex socio-technical systems via safety-in-cohesion. Safety Science 2023, 164. [CrossRef]

- Bortey, L., Edwards, D.J., Roberts, C. and Rillie, I. A Review of Safety Risk Theories and Models and the Development of a Digital Highway Construction Safety Risk Model. Digital 2022, 2, 206–223. [CrossRef]

- Chaphalkar, N.B.; Sandbhor, S.S. Application of neural networks in resolution of disputes for escalation clause using neuro-solutions. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, 2015, 19, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.W. “Application of a PSO-based neural network in analysis of outcomes of construction claims. ” Automation in Construction, 2007, 16, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charehzehi, A. , Chai, C. , Md Yusof, A., Chong, H.Y. and Loo, S.C. “Building information oulling in construction conflict management.” International journal of engineering business management, 2017, 9, 1847979017746257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.N.; Chih, Y.Y.; Le-Hoai, L.; Nguyen, L.D. Project-based A/E/C firms’ knowledge management capability and market development performance: Does firm size matter. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2020, 146, 04020127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Valence, G. Reframing construction within the built environment sector. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2019, 26, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duodu, B.; Rowlinson, S. Intellectual capital, innovation, and performance in construction contracting firms. Journal of Management in Engineering 2021, 37, 04020097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echternach, M.; Pellerin, R.; Joblot, L. Litigation management process in construction industry. Procedia Computer Science 2021, 181, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Academy of management review 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enshassi, A.; Mohamed, S.; El-Ghandour, S. Problems associated with the process of claim management in Palestine: Contractors’ perspective. Engineering, construction and architectural management 2009, 16, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenn, P.; Lowe, D.; Speck, C. Conflict and dispute in construction. Construction Management & Economics 1997, 15, 513–518. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, L.; Edwards, D.J.; Pärn, E.A.; Aigbavboa, C.O. Building design for people with dementia: A case study of a UK care home. Facilities 2018, 36, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriyanti, F.; Adly, E. Lessons Learned in the Use of Dispute Boards to the Settlement of Construction Service Disputes. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction 2022, 14, 04521041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, M.; Zhao, Y.; Plakoyiannaki, E.; Buck, T. Three pathways to case selection in international business: A twenty–year review, analysis and synthesis. International Business Review 2018, 27, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulcher, M., Edwards, D.J., Lai, J.H.K. and Thwala, D.W. (Analysis and modelling of social housing repair and maintenance costs: A UK case study, Journal of Building Engineering, 2022, 52. [CrossRef]

- Gebken, R.J.; Gibson, G.E. Quantification of costs for dispute resolution procedures in the construction industry. Journal of professional issues in engineering education and practice 2006, 132, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, M.; Elsherbeny, H.A. Operational framework for managing construction-contract administration practitioners’ perspective through modified Delphi method. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2020, 146, 04019110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guévremont, M.; Hammad, A. Visualization of delay claim analysis using 4D simulation. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction 2018, 10, 05018002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgun, A.P. and Koc, K. (2022), “The role of contract incompleteness factors in project disputes: A hybrid fuzzy multi-criteria decision approach”, Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Hadi, I.Z. Building a management system to control the construction claims in Iraq. Al-Khwarizmi Engineering Journal 2018, 14, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havila, V.; Medlin, C.J.; Salmi, A. Project-ending competence in premature project closures. International Journal of Project Management 2013, 31, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, T.; Singh, A. Dispute resolution strategy selection. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, C.H.; Wald, A. Toward a wiser projectification: Macroeconomic effects of firm-level project work. International Journal of Project Management 2019, 37, 807–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M. Organisational ambidexterity and firm performance: Burning research questions for marketing scholars. Journal of Marketing Management 2018, 34, 178–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ive, G. and Gruneberg, S., 2000. . The economics of the modern construction sector. Macmillan, London.

- Jagannathan, M.; Delhi, V.S.K. Identifying focus areas to decode the decision to litigate contractual disputes in construction. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2022, 29, 2976–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannathan, M.; Delhi, V.S.K. Litigation in construction contracts: Literature review. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction 2020, 12, 03119001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.; Gold, J.; Claxton, J. Process improvement capability: A study of the development of practice (s). Business Process Management Journal 2019, 25, 1841–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.A.; Ong, T.S.; Ng, S.H.; Muhammad, H.; Ali, N.A. Organizational Aspects and Practices for Enhancing Organizational Project Management Maturity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimchi, J.; Polivka, B.; Stevenson, J.S. Triangulation: Operational definitions. Nursing research 1991, 40, 364–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, J. The methodology of focus groups: The importance of interaction between research participants. Sociology of health & illness 1994, 16, 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kululanga, G.K.; Kuotcha, W.; McCaffer, R.; Edum-Fotwe, F. Construction contractors’ claim process framework. Journal of Construction Engineering and management 2001, 127, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaraswamy, M.M. “Conflicts, claims and disputes in construction. ” Engineering Construction and Architectural Management, 1997, 4, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Iyer, K.C.; Singh, S.P. Understanding relationship between risks and claims for assessing risks with project data. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2020, 28, 1014–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Viswanathan, S.; Neeraj Jha, K. Entry mode sequencing model for emerging international construction firms. Journal of Management in Engineering 2020, 36, 05020002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, R.C.K., Lai, J.H.K., Edwards, D.J. and Hou, H. COVID-19: Research Directions for Non-Clinical Aerosol-Generating Facilities in the Built Environment. Buildings 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; ou, T.W.; Cheung, S.O. Selection and use of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) in construction projects – Past and future research. International Journal of Project Management, 2016, 34, 494–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Jeon, R.K.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.J. Strategies for developing countries to expand their shares in the global construction market: Phase-based SWOT and AAA analyses of Korea. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2011, 137, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Jin, C.; Hyun, C.T. Development of the RACI Model for Processes of the Closure Phase in Construction Programs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtovaara, J.; Seppänen, O.; Peltokorpi, A. Improving construction management with decentralised production planning and control: Exploring the production crew and manager perspectives through a multi-method approach. Construction Management and Economics 2022, 40, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibenstein, H. X-efficiency, technical efficiency, and incomplete information use: A comment. Economic Development and Cultural Change 1977, 25, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. , Meng, F. and Fellows, R. An exploratory study of understanding project risk management from the perspective of national culture. International Journal of Project Management 2015, 33, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, G.; Konstantinou, E.; Geraldi, J.; Sainati, T. The dark side of projects: Dimensionality, research methods, and agenda. Project Management Journal 2022, 53, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maemura, Y.; Kim, E.; Ozawa, K. Root causes of recurring contractual conflicts in international construction projects: Five case studies from Vietnam. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2018, 144, 05018008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarem, A., Abdul-Malak, M.A. and Srour, I., 2012. Managing the Period Preceding the Calling for a DAB’s Decision. In Construction Research Congress 2012: Construction Challenges in a Flat World ( 71-79).

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization science 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martek, I. , 2022. International Construction Management: How the Global Industry Reshapes the World.

- Martinsuo, M.; Geraldi, J. Management of project portfolios: Relationships of project portfolios with their contexts. International Journal of Project Management 2020, 38, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, R.L.; Tan, K.H.; Marzec, P.E. Organisational ambidexterity within process improvement: An exploratory study of four project-oriented firms. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 2015, 26, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B.S. The conflict paradox: Seven dilemmas at the core of disputes. John Wiley & Sons. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Midler, C., Maniak, R. and de Campigneulles, T. Ambidextrous program management: The case of autonomous mobility. Project Management Journal 2019, 50, 571–586. [CrossRef]

- Mirzaee, A.M. , Hossieni, M.R. and Martek, I. Optimal Buyer Credit Arrangements for Chinese Procured Dam-building Projects: An Iranian Perspective. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering 2022, 26, 4984–4996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaee, A.M. , Hosseini, M.R., Martek, I., Rahnamayiezekavat, P. and Arashpour, M., 2022b. Mitigation of contractual breaches in international construction joint ventures under conditions of absent legal recourse: Case studies from Iran. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Miterev, M.; Engwall, M.; Jerbrant, A. Exploring program management competences for various program types. International Journal of Project Management 2016, 34, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miterev, M. , Turner, J. R. and Mancini, M. “The organization design perspective on the project-based organization: A structured review”, International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 2017, 10, 527–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R.; Drouin, N.; Sankaran, S. Modeling organizational project management. Project Management Journal 2019, 50, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafe Assafi, M. , Hossain, M.M., Chileshe, N. and Datta, S.D. (2022), “Development and validation of a framework for preventing and mitigating construction delay using 4D BIM platform in Bangladeshi construction sector”, Construction Innovation, ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Obi, L.; Hampton, P.; Awuzie, B. Total interpretive structural modelling of graduate employability skills for the built environment sector. Education Sciences 2020, 10, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, I.I.I. O’Reilly, I.I.I.; CA; Tushman, M.L. Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. In Academy of management Perspectives; 2013; Volume 27, pp. 324–338. [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Chan, A.P.; Yao, Y.; Mazher, K.M. Conflict prevention measures for public–private partnerships in developing countries. Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction 2019, 24, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Manu, D.-G. , Ofori-Yeboah, E., Badu, E., Kukah, A.S.K. and Edwards, D.J. (2022), "Assessing effects of moral hazard -related behaviours on quality and satisfaction of public-private-partnership (PPP) construction projects: Case study of Ghana", Journal of Facilities Management, ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Parchami jalal, M.; Moradi, S.; Shirazi, M.Z. Claim management office maturity model (CMOMM) in project-oriented organizations in the construction industry. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2023, 30, 74–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchami Jalal, M. , Yavari Roushan, T. , Noorzai, E. and Alizadeh, M. “A BIM-based construction claim management model for early identification and visualization of claims”, Smart and Sustainable Built Environment 2021, 10, 227–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petro, Y.; Ojiako, U.; Williams, T.; Marshall, A. Organizational ambidexterity: A critical review and development of a project-focused definition. Journal of Management in Engineering 2019, 35, 03119001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Project Management Institute (PMI) (2017), A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMI® Guide, 6th ed., Project Management Institute, Pennsylvania, PA.

- Rijke, J.; van Herk, S.; Zevenbergen, C.; Ashley, R.; Hertogh, M.; ten Heuvelhof, E. Adaptive programme management through a balanced performance/strategy oriented focus. International Journal of Project Management 2014, 32, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, C. and Edwards, D.J. (2022) Post-occupancy evaluation: Identifying and mitigating implementation barriers to reduce environmental impact, Journal of Cleaner Production. [CrossRef]

- Shahhosseini, V. and Hajarolasvadi, H. “A conceptual framework for developing a BIM-enabled claim management system.” International Journal of Construction Management, 2018, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Shalwani, A.; Lines, B. Using issue logs to improve construction project performance. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2022, 29, 896–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Müller, R.; Turner, J.R. Measuring program success. Project Management Journal 2012, 43, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenhar, A.; Holzmann, V. The three secrets of megaproject success: Clear strategic vision, total alignment, and adapting to complexity. Project Management Journal 2017, 48, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaratne, C.; Wang, C.L. Organisational ambidexterity in UK high-tech SMEs: An exploratory study of key drivers and barriers. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 2018, 25, 1025–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, W.; Kang, Y. Performance indicators for the claim management of general contractors. Journal of Management in Engineering 2020, 36, 04020070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, W.; Kwak, Y.H.; Kang, Y. Relationship between consistency and performance in the claim management process for construction projects. Journal of Management in Engineering 2021, 37, 04021068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.K.; Jha, K.N. Dispute resolution and litigation in PPP road projects: Evidence from select cases. Journal of Legal Affairs and Dispute Resolution in Engineering and Construction, 2020, 12, 05019007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatiou, D.R.I.; Kirytopoulos, K.A.; Ponis, S.T.; Gayialis, S.; Tatsiopoulos, I. A process reference model for claims management in construction supply chains: The contractors’ perspective. International Journal of Construction Management 2019, 19, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo-Torres, J.; Roehrich, J.K.; Lewis, M.A. Ambidexterity, performance and environmental dynamism. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 2017, 37, 282–299. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, H.C. Tan, H.C. and Anumba, C. 2010, December. Web-based construction claims management system: A conceptual framework. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Construction and Real Estate Management (ICCREM 2010) ( 1-3).

- Taylor, K. , Edwards, D.J., Lai, J.H.K., Rillie, I., Thwala, W.D. and Shelbourn, M. (2022) Converting commercial and industrial property into rented residential accommodation: Development of a decision support tool, Facilities, ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. [CrossRef]

- Tellis, W. Application of a case study methodology. The qualitative report 1997, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Tochaiwat, K.; Chovichien, V. Contractors construction claims and claim management process. Engineering Journal of Research and Development 2004, 15, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Trinkūnienė E. and Trinkūnas, V. Mediation as an alternative means to the business dispute resolution. Business and management 2022, 946–952.

- Trzeciak, M.; Kopec, T.P.; Kwilinski, A. Constructs of Project Programme Management Supporting Open Innovation at the Strategic Level of the Organisation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2022, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R. How does governance influence decision making on projects and in project-based organizations? Project Management Journal 2020, 51, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanagunas, S. Max Weber's Authority Models and the Theory of X-Inefficiency: The Economic Sociologist's Analysis Adds More Structure to Leibenstein's Critique of Rationality. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 1989, 48, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Wu, G. A Systematic Approach to Effective Conflict Management for Program. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244019899055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilms, R.; Winnen, L.A.; Lanwehr, R. Top Managers' cognition facilitates organisational ambidexterity: The mediating role of cognitive processes. European Management Journal 2019, 37, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Zhao, X.; Zuo, J.; Zillante, G. Effects of team diversity on project performance in construction projects. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2019, 26, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Lu, W.; Flanagan, R.; Ye, K. Diversification in the international construction business. Construction management and economics 2018, 36, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K., 2009. Case study research: Design and methods (Vol. 5). Sage.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).