1. Introduction

In the 4th industrial revolution, the

Internet of Technology (IoT) emerges as a mega-trend technology that interconnects uniquely identifiable smart objects over the Internet and supports

machine-to-machine (M2M) communication. Hence, the IoT can be seen as a massively distributed network of numerous smart IoT-enabled devices [

1]. IoT is an essential and rapidly adopting technology to transform the traditional healthcare system into a connected, smart, proactive, and specialist-focused healthcare solution [

2]. The current healthcare industry quickly embraces advanced smart medical devices induced with IoT facets to improve treatment quality, increase productivity, reduce errors, cutoff expenditures, automate resource management, and provide enhanced and never-before Quality-of-Services (QoS), thus shaping the

Internet of Healthcare Things (IoHT) [

3,

4]. Cloud-based services are incorporated into the IoHT to facilitate real-time remote monitoring of patients in both normal and emergency conditions.

IPv6 over Low Power Wireless Personal Area Network (6LoWPAN) and

Wearable Wireless Sensors Network (W-WSN) are crucial parts of the IoT evolution [

5]. Many IoT applications, including healthcare, use 6LoWPAN-enabled motes to sense the vital parameters of the applications’ vicinity [

6]. Several 6LoWPAN-based resource-limited wearable and non-wearable medical sensing

things (devices) are used in IoHT [

7]. Some primary reasons that justify the incorporation of IoT in the healthcare system are as follows [

8]:

Real-time remote health monitoring

Ambient Assisted Living

Technology-driven medical solution

Fast and time-bound diagnosis of diseases.

Reduced treatment cost

Fewer treatment errors.

Automated workflow of patient care.

Affordability

End-to-End connectivity

M2M communication

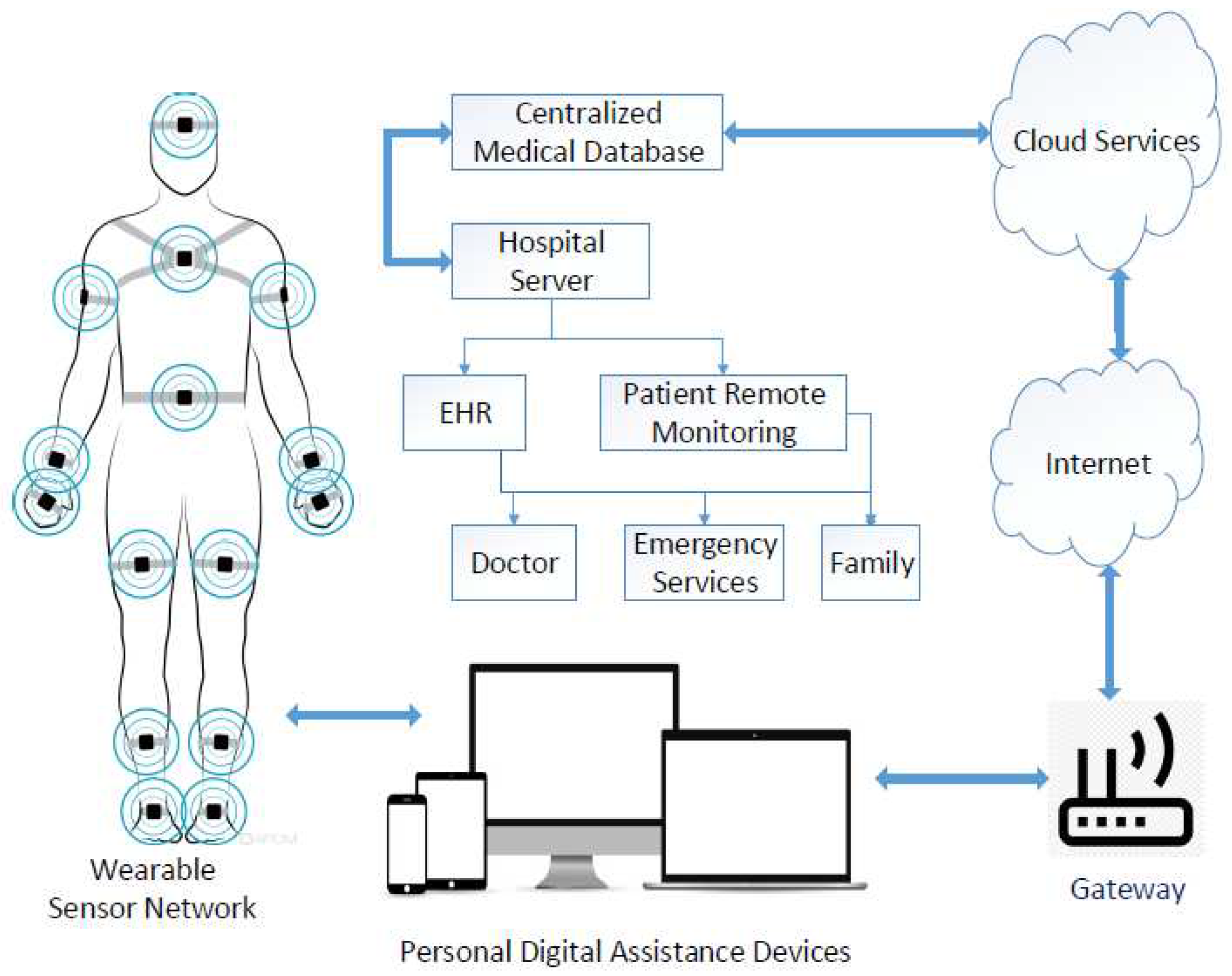

An overview of IoHT is illustrated in

Figure 1.

IoHT interconnects numerous IoT-enabled medical devices and smart wearable and non-wearable medical sensors, supporting communication and internet connectivity. It can transform traditional healthcare into a smart, connected, proactive, and future-centric healthcare infrastructure [

9]. However, IoHT is a critical application that deals with highly personal and private information, including crucial medical data about the patient. Due to that, it is the most popular system among attackers and puts patients’ personal and private data at a constant security risk [

10]. The discussion regarding the security of IoHT goes far beyond securing the physical interfaces and firmware of IoHT devices [

11]. The security perspective in IoHT should include the security of web, cloud, and mobile interfaces, secured network services, local storage, and third-party APIs. The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) listed vulnerabilities according to attack surfaces related to IoT-based medical devices [

12]. The following section will discuss possible attacks on the IoHT and related security concerns.

Monitoring physiological parameters from the patient’s body is a primary task of PC-IoHT. These collected medical vitals are then sent to the cloud via the sink node of PC-IOHT over internet connectivity. Therefore, this work considers two operation modes, PC-IoHT (i.e., normal and emergency), for health monitoring. These operating modes define the per-minute count of data sensing and transmissions. We presumed that in routine health monitoring, systematic data collection causes a lot of redundant medical data in the system, leading to the wastage of scarce resources in PC-IoHT. Thus, it is decided to send just one packet per minute by each mote of PC-IoHT that transmits in the normal mode. However, in the case of any medical emergency, a systematic collection of medical parameters is required for continuous (no-gap) health monitoring. Therefore, in emergency mode, each mote of PC-IoHT senses and transmits medical vitals every 10 seconds.

In this work, we extensively analyze the performance of resource-constraint 6LoWPAN-RPL-based patient-centric IoHT (PC-IoHT) under blackhole, Rank, and DoDAG attacks. We select these attacks from all three categories (defined in

Section 2). Blackhole is a topology-based attack, Rank is a traffic-based attack, and DoDAG is a resource-based attack. For enhanced investigation of attacks’ impact on PC-IoHT, various malicious intruders are induced in PC-IoHT.

(in the first case) and

(in another) of all motes are assumed to be compromised nodes in the PC-IoHT. The PC-IoHT, considered in this work, consists of 10 sensing nodes and one sink node; therefore, there are 2 and 4 malicious nodes in separate cases.

The performance of PC-IoHT hit with these three attacks is then evaluated in terms of the number of packets transmitted, the number of data messages exchanged, the overall throughput of the network, the average power consumption, the average radio duty cycle (RDC), the number of successful packets, the packet reception ratio (PDR), and the message delivery ratio (MDR) based on the result of the simulation performed on Cooja simulator under the Contiki operating system environment.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 categorically discusses possible attacks along with various security concerns related to PC-IoHT. Next,

Section 3 discusses the considered attacks and their implementation in the PC-IoHT environment. Thereafter,

Section 4 exhibits a comprehensive performance evaluation of PC-IoHT under blackhole, rank, and DoDAG attack with 2/4 attackers for both normal and emergency operating modes. Finally, the summary of this work is concluded in

Section 5.

2. Security Concerns and Categorisation of Attacks related to PC-IoHT

The particularities of Low-Power Lossy networks (LLNs) such as limited resources (memory, power, and computation), infrastructure-less dynamic topology, non-reliable wireless connectivity, and the possibility of physical temper, make them highly vulnerable and hard to defend from security attacks. Though RPL (a standard routing protocol for LLNs) consists of many security-ensuring mechanisms, it is still exposed to many security attacks and requires strict security policies to be implemented.

Internet of Healthcare Things (IoHT) is most preferably targeted for security attacks that put critical personal data at constant risk of attacks. Therefore, it is highly essential to identify security and privacy issues [

13]. A thorough understanding of security requirements, threats, vulnerabilities, attacks, and countermeasures modeling is sorely needed [

14]. Existing security solutions (designed explicitly for WSN) are inadequate to fulfill the security needs of IoT technology. Thus, new security defense mechanisms must be developed to counter security challenges from an IoT perspective.

Table 1 and

Table 2 shows some primary security requirements and challenges regarding 6LoWPAN-RPL based PC-IoHT.

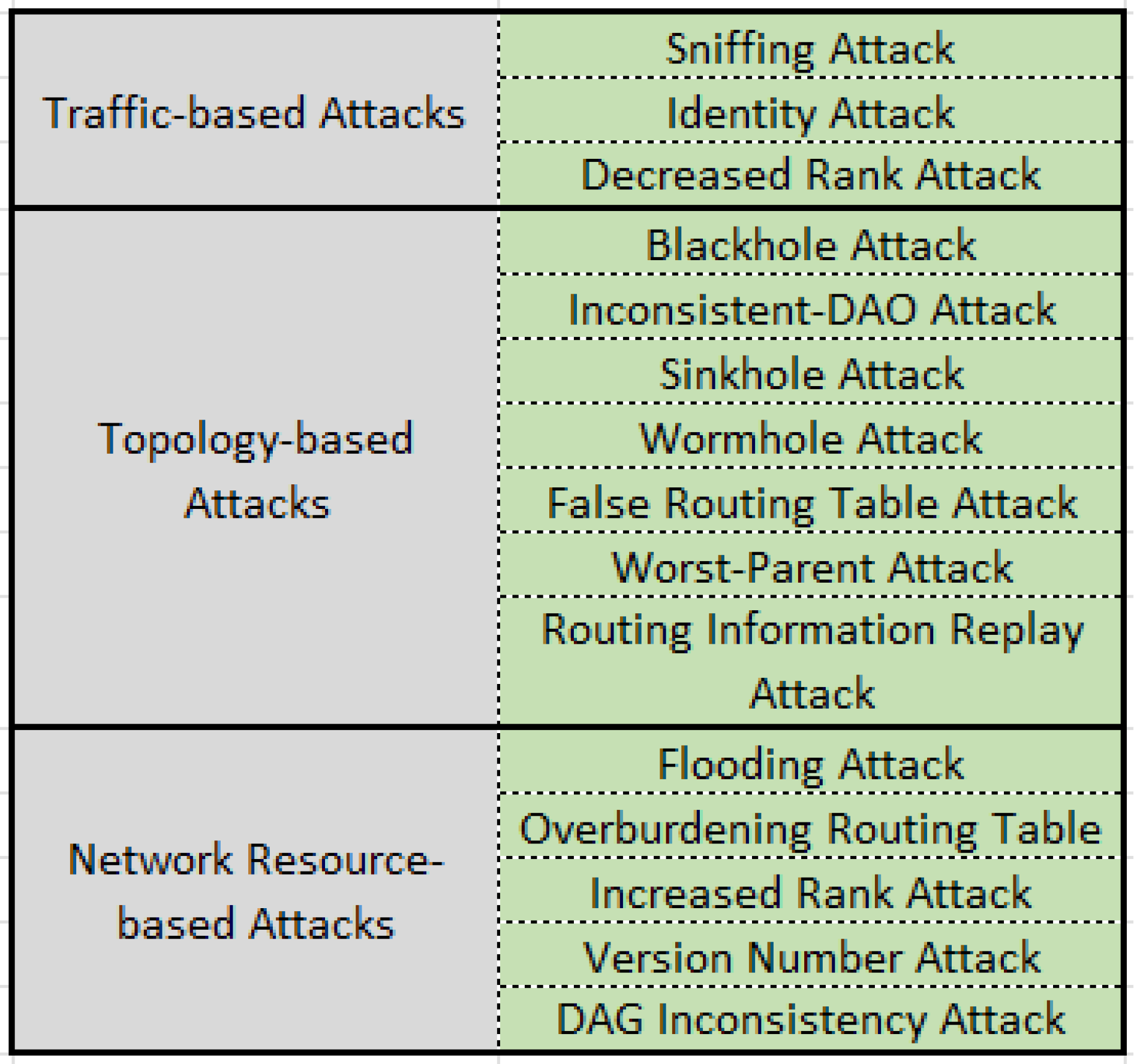

Security of an IoT network is impossible with just one security strategy that ultimately secures the IoT network. However, security in the IoT is a multi-layer approach that should integrate schemes that broadly secure data traffic, the network’s topology, and network resources [

15]. Thus, we majorly categorize attacks on RPL-based IoT networks into three subcategories:

Figure 2 exhibits the possible attacks in 6LoWPAN-based PC-IoHT under the above-mentioned categories [

16]. Next, attacks considered in this paper for performance evaluations are discussed below.

3. Discussion on considered attacks

Rank Attack

In an effort to persuade nearby nodes to relay the data packets through them, the malicious node performing the rank attack modifies the rank value in the DIO message to perform decreased or increased rank attacks. Therefore, loops form that waste resources [

17].

In

Decrease Rank attack, attackers with a lower rank value advertise it to the other DoDAG nodes through DIO messages. This will lead to the DODAG’s majority of nodes selecting the attackers as their preferred parents [

18]. It is shown that more nodes have access to the root node via attackers due to a decrease in rank attacks Which pave the way for the eavesdropping and manipulation of a significant portion of network traffic [

19,

20].

In RPL, the closed node to the sink has the lowest rank and manages more traffic. In this attack, the malicious node falsely advertises its lower rank illegally in the DIO messages and claims its outperformance. Due to this, legitimate nodes with higher ranks are attracted to the malicious node. Then, the legitimate nodes connect themselves to the DoDAG via the malicious node. Thereafter, the malicious node can perform malicious activities on the network. This attack is also known as

Sinkhole attack [

21].

Similarly, an increased rank attack promotes a higher rank value to persuade the neighbors to select a different parent. A child of the attacker in its sub-DODAG searches for a different preferred parent as the attacker descends further into DODAG. This causes the loop to form [

20].

Blackhole Attack

A malicious intruder in this attack captures all the packets being forwarded toward the sink through it [

22]. It is one of the dangerous attacks that cause the loss of enormous amounts of information, and the situation worsens if this attack is combined with the sinkhole attack [

23]. Suppose the intruder is a crucial intermediate node responsible for forwarding packets of many child nodes. In that case, the attacker isolates all those nodes, and the attack becomes a

Daniel-of-service (DoS) attack [

24]. If the attacker selectively forwards the incoming packet by discarding specific child nodes, this attack can be seen as

grayhole attack [

25].

Malicious node performing the blackhole attacks drops all the packets which are being forwarded toward the sink (root) node. This attack is carried out by the node in two steps.

First, by performing the Sinkhole attack. The attacker node solicits neighbors to select it as their parent by advertising a false low-rank value.

Second, Depending on predetermined rules, it might discard some packets (performing a Selective Forward attack). Alternatively, discard all packets from other nodes (performing a Blackhole attack).

Blackhole attacks drastically impact network efficiency and performance. In reference [

26,

27], the authors evaluate the effect of a blackhole attack in an RPL environment and show its higher impact on packet delivery ratio (PDR), end-to-end delay, the overhead of control packets, and power depletion. The process of blackhole attack implementation is exhibited in the algorithm (1).

|

Algorithm 1 The process of Blackhole attack |

Require: of malicious node

if of node matches of malicious node then

Reduce the value of

Allocate higher to the Parent nodes

Drop all packets coming from nodes other than the parent.

else

Calculate using defined process

end if

|

DoDAG Attack

A malicious node performing a DoDAG inconsistency attack manipulates the RPL IPv6 header options used to monitor DODAG inconsistencies, which causes the target to drop packets [

28]. It may result in a denial of service and an increase in control overhead, which affects the constrained devices’ limited energy source. Furthermore, a malicious node can alter all the packets it forwards using a DoDAG inconsistency attack so that the next-hop node always drops them. It leads to the creation of a black hole, which is hard to detect and counteract [

29]. In order to defend against DoDAG inconsistency attacks, RPL uses a fixed threshold without considering the black-hole scenario. A node ignores all subsequent messages of this type after receiving a predetermined number of packets with the appropriate RPL IPv6 header options.

In RPL, the inconsistent DAG is detected using a non-matching rank-direction relationship of a packet that causes loops in the network. In this attack, a malicious node alters the rank-error flag or adds a new flag in the header. As a result, it causes an immediate reset of the DIO trickle timer of the targeted node. Due to that, the targeted node starts frequent transmissions of DIO, making the RPL network unstable, consuming more energy, and making the link unavailable. Furthermore, the neighbors of the targeted node have also been affected by this attack, as they now have to process far more packets. Moreover, if the target node is made to discard all the packets, it can cause a blackhole attack by isolating a sub-network.

In the following section, a detailed analysis of blackhole, rank, and DoDaG (most common ones from each category) attacks on PC-IoHT is made in the section below.

4. Simulation-based Performance Analysis

To evaluate the performance of resource-restricted 6LoWPAN-based PC-IoHT, the simulation is performed on Cooja simulator under Contiki operating system (OS). Contiki is an open-source OS for low-power, resource-constraint IoT networks. Its built-in TCP/IP stack and event-driven kernel with lightweight preemptive scheduling make it possible to use it in IoT applications. Contiki facilitates multitasking with only 10KB of RAM, 30KB of ROM, and a built-in GUI. It runs on tiny low-power microcontrollers, provides standard low-power wireless communication for various hardware platforms, and supports application development for efficient use of resources. Due to the aforementioned properties, Contiki is prominently used in commercial and non-commercial IoT applications. Cooja is a java-based cross-layer simulator for WSN distributed with Contiki OS. Cooja assists simulation from the physical to the application layer and enables the emulation of sensors on different hardware platforms. It allows the simulation of large or small networks of Contiki motes.

In this section, we performed simulations to analyze the performance of the considered PC-IoHT network (consisting of 10 sender and 1 sink Tmote-Sky motes) under

Rank, DoDAG, and Blackwhole attacks. Depending on the mode of operation of PC-IOHT (i.e., normal or emergency), the simulation-based performance analysis is performed under two cases, i.e.,

&

). We used an extensive set of performance evaluation parameters such as

number of packets generated, number of messages, number of packets successfully received at the sink, message delivery ratio, packet reception ratio, throughput, and overall power consumption to evaluate the network performance of PC-IoHT under different attacks. These performance parameters are discussed in their respective subsections below for both operation modes. The profound examination of attacks’ impact is done by splitting attack analysis into two parts (with various malicious nodes). We used

(i.e., two out of 10) malicious nodes in the first part, and the second part has

(i.e., four out of 10) malicious nodes. To better understand the impact of these attacks on PC-IoHT, we compared the performance with the no-attack scenario.

Table 3 shows the parameters and their respective values used in the simulation.

The PC-IoHT network, which we considered, is supposed to operate in two modes: (i) Normal mode; (ii) Emergency mode. Normal mode is when the patients’ vitals (under normal conditions) are regularly captured by medical sensing devices and posted to the sink for further processing. This periodic interval is 1 minute for the normal mode of PC-IoHT. The collected physiological data is sent to the sink every minute. However, in the case of some medical emergencies (which can be detected by abnormal vitals), the physiological parameters need to be monitored in very short instances. Hence, in such a case, medical data is captured every 10 seconds and transmitted to the sink for further investigation. In the emergency operating mode, the data transmission rate is six times higher than in the normal mode. It indeed degrades the network performance in the presence of malicious activities. The following subsections analyze the parametric performance of PC-IoHT hit by 2 and 4 malicious nodes (out of 10 motes) of different attacks when operated in normal and emergency modes.

4.1. Result analysis

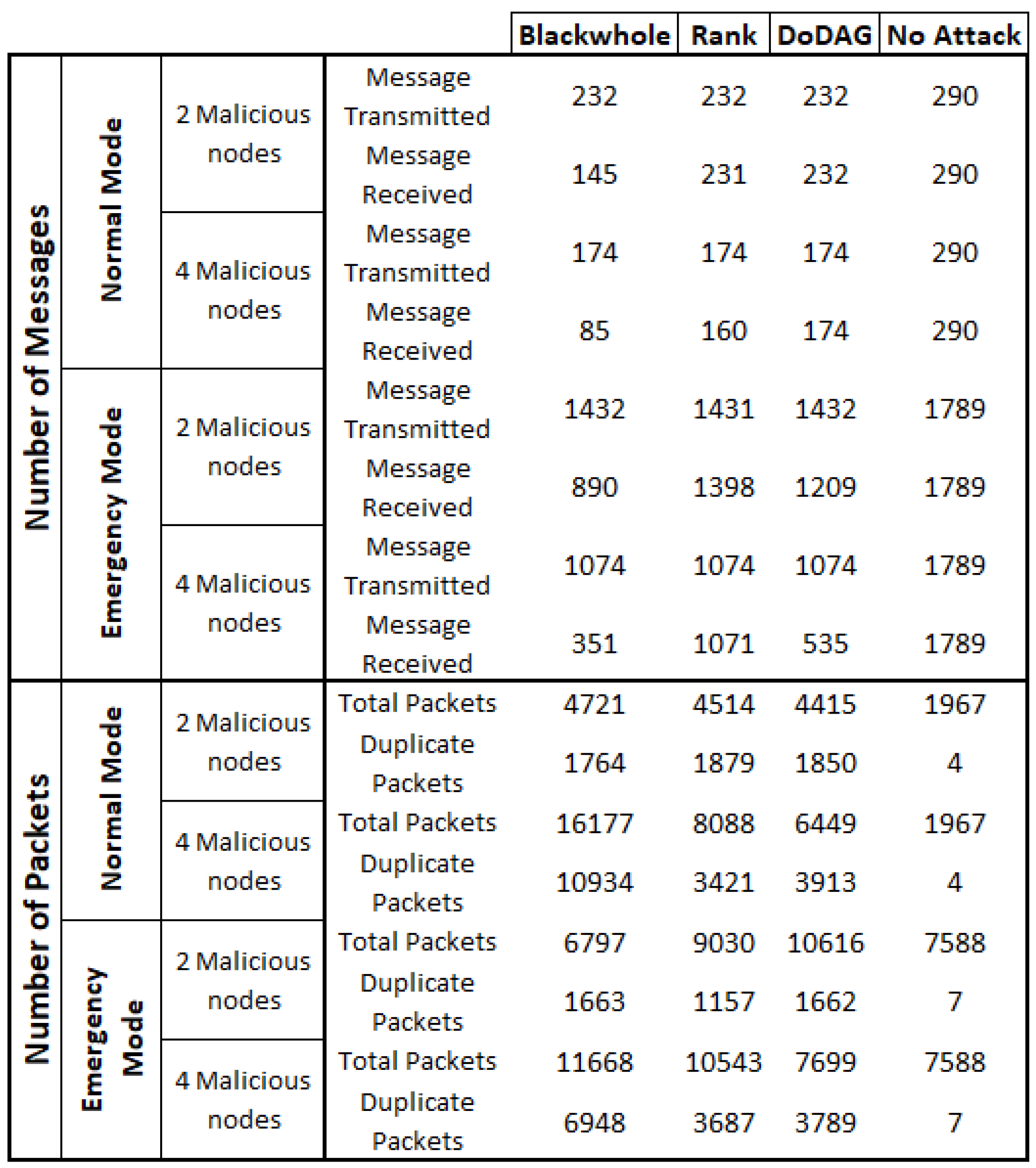

Figure 3 depicts the number of packets generated (in both modes) by PC-IoHT when hit with Rank, DoDAG, and Blackhole attacks. The performance is compared with the no-attack scenario for the respective parameters. As observed in the figure, for both parts (two malicious and four malicious), the number of generated packets in the no-attack scenario is significantly lower than all others, and the blackhole attack has the highest number of packets. This trend is due to the network’s high number of retransmitted packets. The PC-IoHT under no-attack has almost no retransmission, while most packets are not delivered to the intended destination (sink) when a blackhole attack occurs. However, in emergency mode, it is noted that the PC-IoHT generates packets more steadily under no attack. The total number of packets exchanged between motes and the sink, and the number of duplicate packets are also exhibited in the same figure (

Figure 3), for all the mentioned attacks. As is notable, PC-IoHT hit with the blackhole attack performs the worst among them. It attains the highest number of total packets, most of which are duplicates. It is because blackhole malicious motes remove all packets that should be forwarded upwards. The situation worsened with increased malicious motes as duplicate packets significantly grew. For instance, in the case of four malicious motes, the number of packets under blackhole attack is more than 8X what we get in a no-attack situation. The duplicate packet, in this case, increases to 10934 from just 4 in the no-attack case.

It is noticed that PC-IoHT, without any malicious motes, generates more data messages because, in other cases, malicious motes either do not transmit any messages or send false messages to interrupt the communication. The gap in the number of messages significantly increases when the transmission rate rises to every 10 seconds. If we talk about the total number of data messages generated throughout the simulation, then around 300 messages are generated by all ten motes, ideally (no-attack scenario). Thus, the sink must receive all transmitted messages without losing any. However, even in the no-attack case, it is not possible. The messages are dropped or lost due to buffer loss or channel loss.

Therefore,

Figure 3 also illustrates the total number of messages transmitted and received within the

(simulation time). We show that 290 messages are transmitted and received in the no-attack case. However, if we compare the blackhole attack case with this, just half of it (i.e., 145) packets are received in the normal operation mode of PC-IoHT (perform most inferiorly). In this case, the two malicious nodes block the same number of transmitted messages. The performance drastically deteriorates when malicious nodes increase (from 2 to 4). The increased transmission rate (i.e., emergency mode) further degrades the number of received messages significantly.

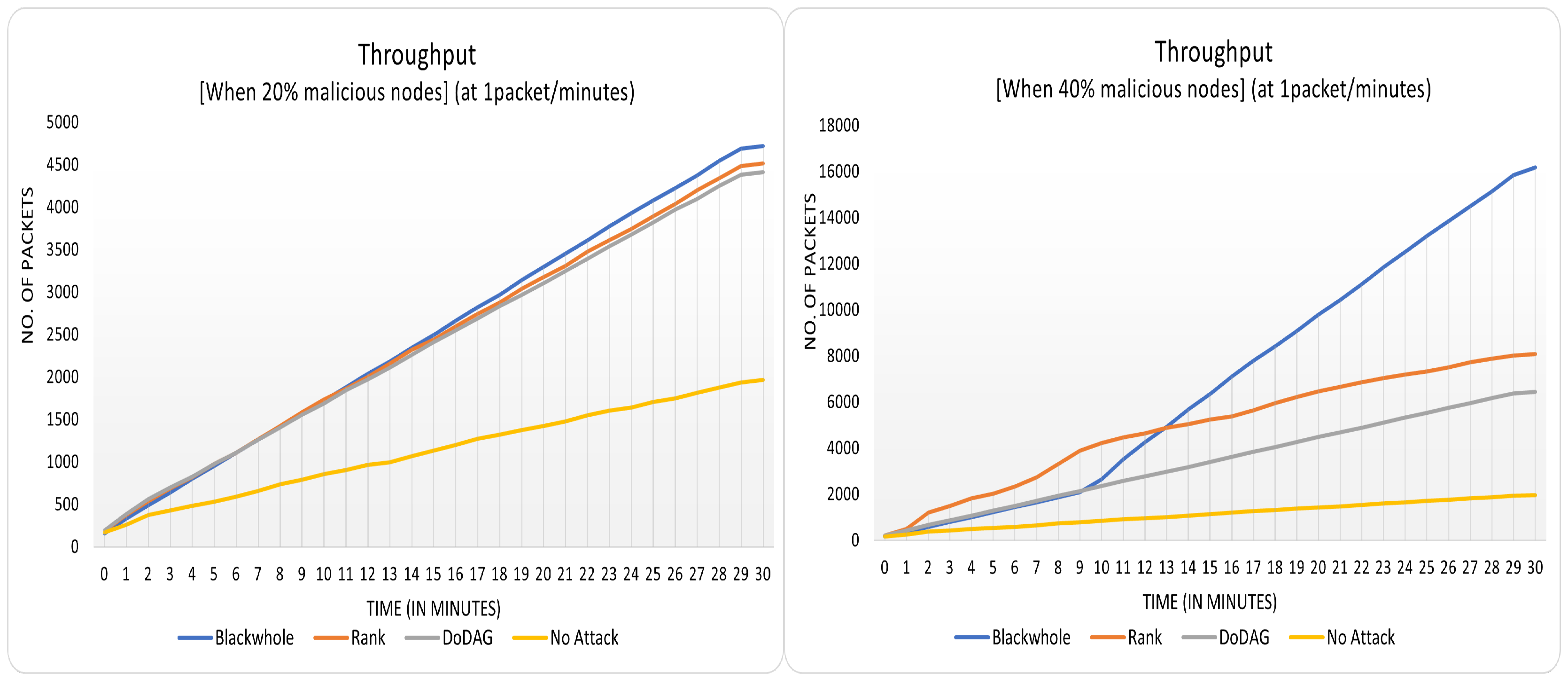

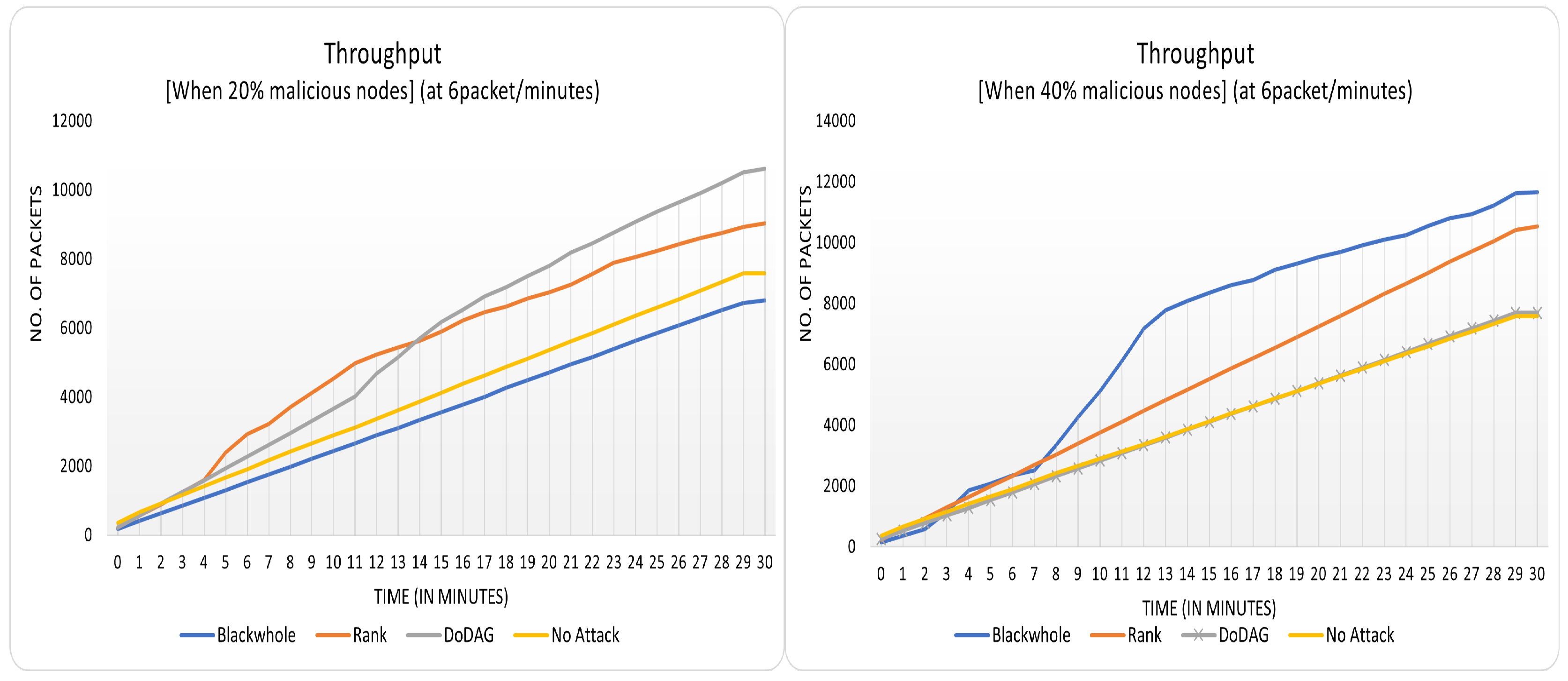

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 display the overall throughput of the PC-IoHT under attack and no attack in both operational modes. The illustration of plots confuses readers in that it seems like the throughput of the no-attack case is the least of all. However, here one important point needs to be raised to counter this phenomenon; it is that, as mentioned in the

Figure 3, the least number of packets have been exchanged in the no-attack scenario, and the blackhole attack has the highest. The throughput of no-attack is lower than others because fewer packets are lost and re-transmitted.

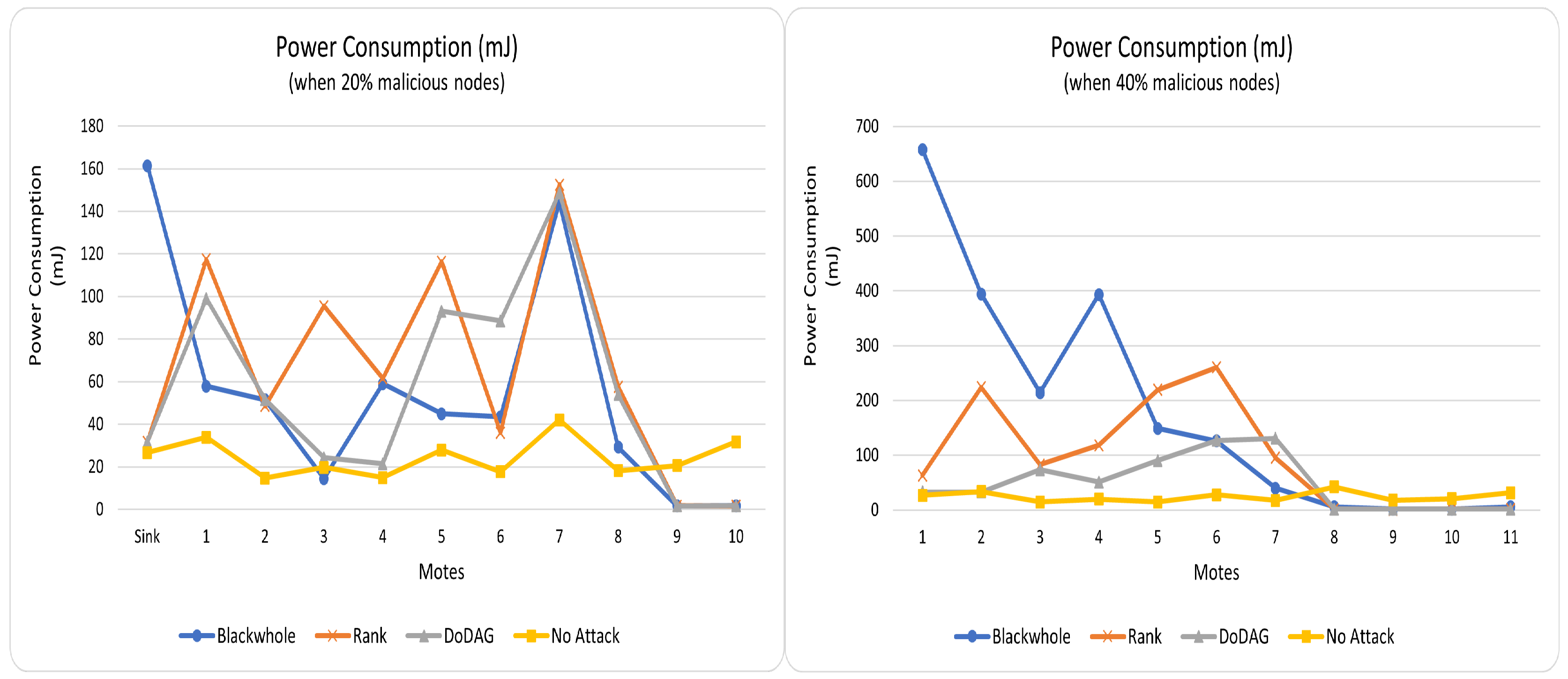

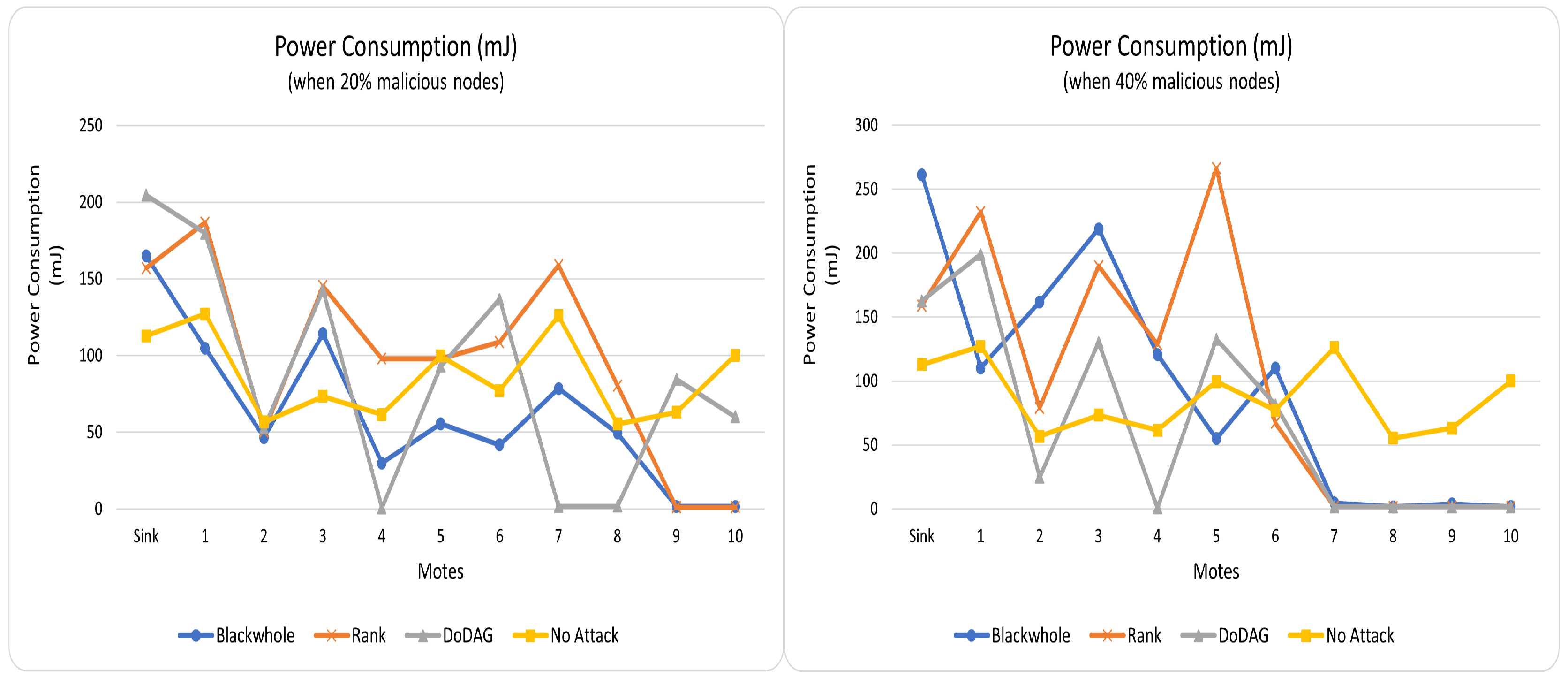

The depletion of current in

Tmote-Sky (type of motes used in PC-IoHT) is

in reception,

in transmission,

in MCU-on, and

in idle [

30]. Thus, the exhaustion of energy resources depends on the number of transmissions and receptions. The overall power consumption in

normal and emergency mode is depicted for both 2 and 4 malicious nodes in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. It has been noted in all situations that PC-IoHT consumes minimal energy resources when no malicious activity exists. It is because all the motes of PC-IoHT are alive and efficiently utilize the energy resources throughout the simulation in the no-attack scenario. However, it is noticed that some of the motes in rank, DoDAg, and blackhole attacks barely consume any power; these are malicious motes that, most of the time, block incoming packets from being forwarded toward their destination. As mentioned, the maximum number of packets is exchanged due to many retransmission attempts when PC-IoHT has blackhole malicious motes. Hence, in this case, the power usage is more than in others.

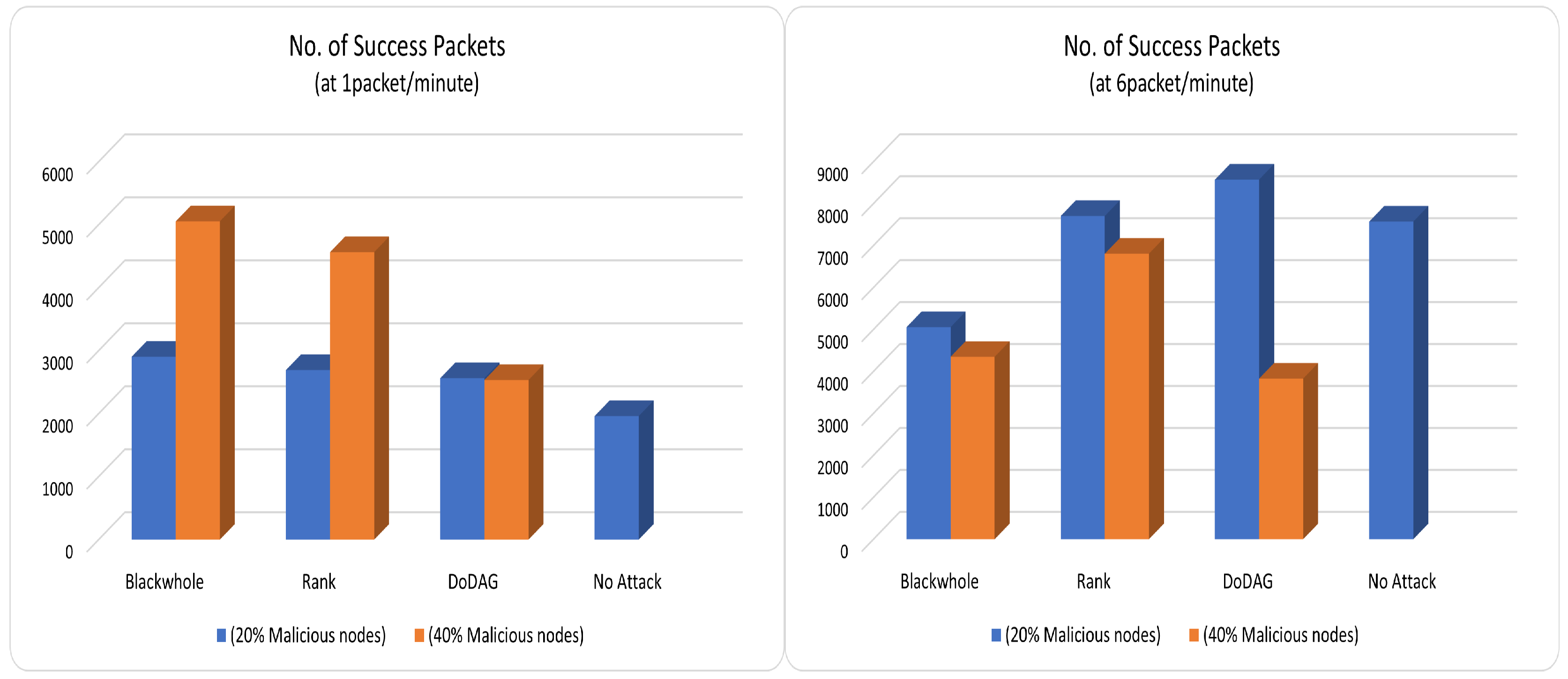

The number of packets that successfully reached the sink (for both operating modes) is exhibited in

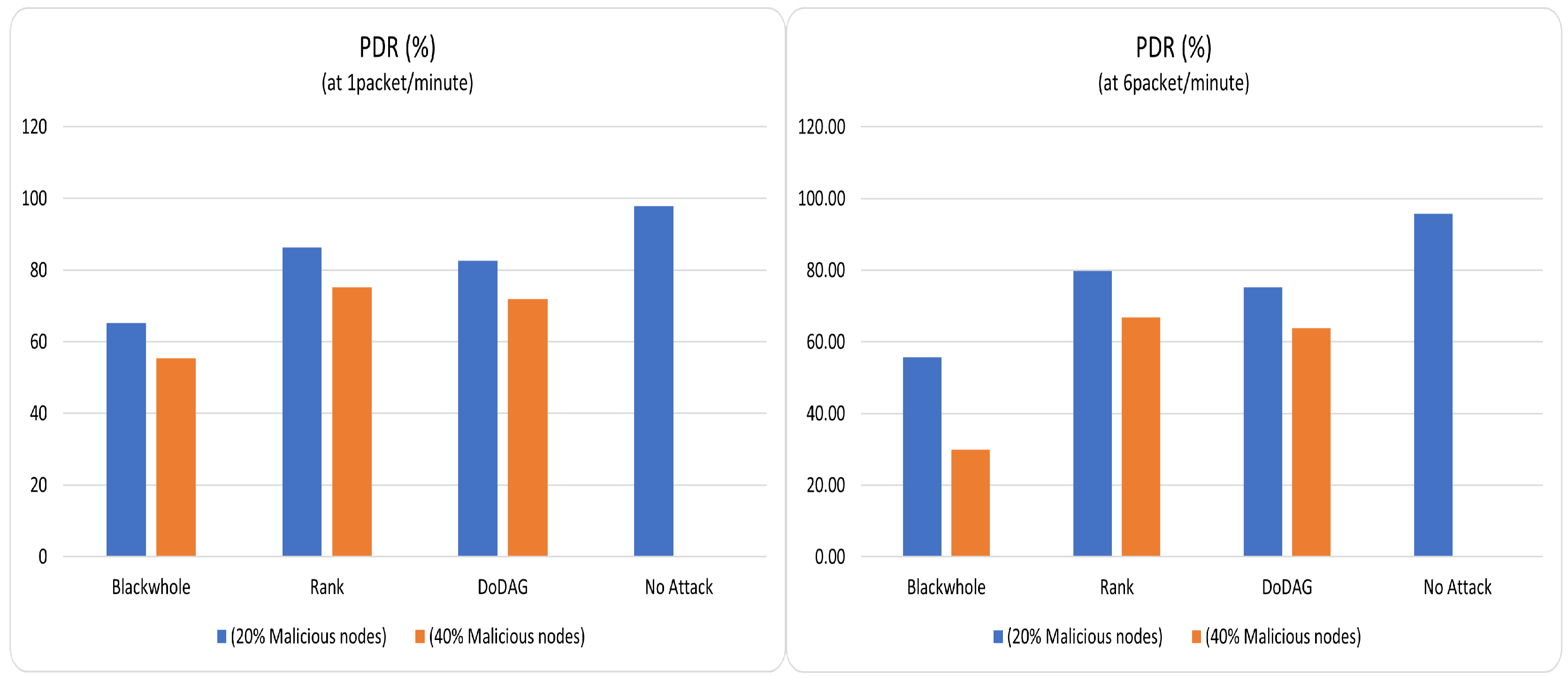

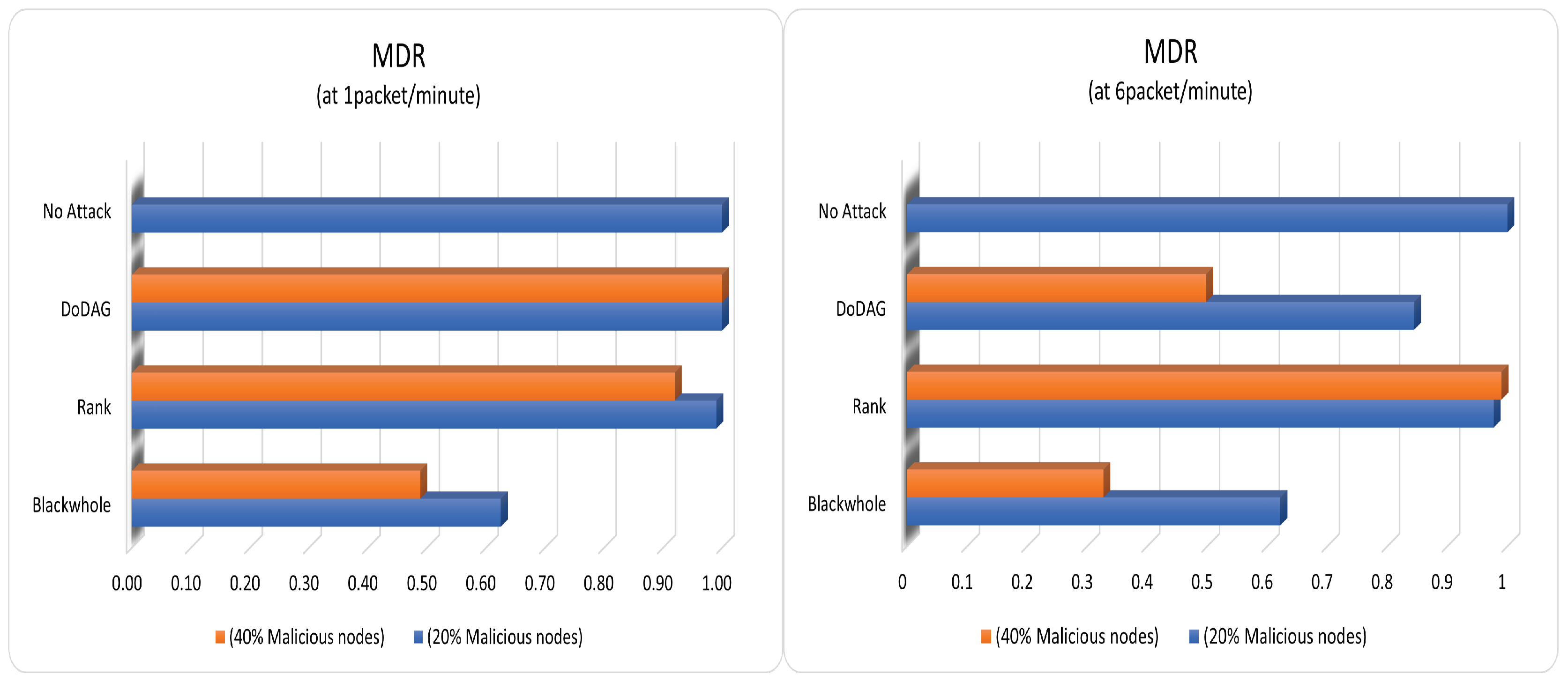

Figure 8. Keeping in mind the number of retransmissions, it is observed that the no-attack case outperforms all others in delivering packets successfully to the sink. The blackhole case is the worst due to the most retransmitted packets. Following the same trend, the packet reception (delivery) ratio (PDR/PRR) (displayed in

Figure 9) of the no-attack PC-IoHT surpasses others. As expressed in

Figure 10, the ratio of message delivery (MDR) traces the same pattern as PDR (for both data rates). The MDR of the no-attack scenario attains MDR as 1 because no message is lost in the transceiving. As a result, the DoDaG and rank attack cases are closed to the no-attack case with fewer lost or delayed messages. However, the blackhole attack case has minimal MDR because of the many lost messages. We finally summarize the outcome of this study in the following section.

5. Conclusion

Handling personal and private medical information makes IoHT highly vulnerable to security attacks and puts critical data at constant risk. We have discussed several attacks and threats that are possible in RPL-based PC-IoHT. In this work, to analyze the impact of blackhole, rank, and DoDAG attacks on resource-restricted 6LoWPAN-RPL based PC-IoHT, the simulation is performed on Cooja simulator over Contiki OS. The performance of PC-IoHT under attack is examined on two operating modes that are based on data rate, i.e., 1-packet/minute (normal mode) and 6-packets/minute (emergency mode). Furthermore, the performance is investigated with 2 and 4 malicious nodes (out of 10 motes) induced in PC-IoHT. An analysis of performance evaluation parameters such as the number of packets and data messages, throughput, power consumption, PRR, MDR, and success packets are scrutinized to assess the attacks’ effect. A careful observation of these extensive results concluded that a blackhole attack is the worst among them. It drastically deteriorates the overall performance of PC-IoHT. Furthermore, the blackhole attack can easily be converted into a sinkhole or gray hole attack, worsening the situation even more. In future work, we will try to propose a security mechanism to defend PC-IoHT from blackhole, sinkhole, and grayhole attacks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.V., N.C.; Formal analysis, H.V., N.C., B.J.C; Investigation, H.V., N.C., L.A., A.K; Methodology, H.V., A.K, B.J.C; Resources, H.V., B.J.C; Writing – original draft, H.V.; Writing – review & editing, H.V., A.K, B.J.C; Visualization, H.V., N.C., L.A.; Validation, H.V., N.C., L.A.,B.J.C; Supervision, N.C., L.A.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the MSIT Korea under the NRF Korea (NRF-2022R1A2C4001270) and the Innovative Human Resource Development for Local Intellectualization support program (IITP-2023-RS-2022-00156360) supervised by the IITP.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Souri, A.; Hussien, A.; Hoseyninezhad, M.; Norouzi, M. A systematic review of IoT communication strategies for an efficient smart environment. Transactions on Emerging Telecommunications Technologies 2022, 33, e3736. e3736 ETT-19-0271.R2, doi:10.1002/ett.3736. [CrossRef]

- Haghi Kashani, M.; Madanipour, M.; Nikravan, M.; Asghari, P.; Mahdipour, E. A systematic review of IoT in healthcare: Applications, techniques, and trends. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2021, 192, 103164. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2021.103164. [CrossRef]

- Verma, H.; Chauhan, N.; Chand, N.; Awasthi, L.K. Buffer-loss estimation to address congestion in 6LoWPAN based resource-restricted ‘Internet of Healthcare Things’ network. Computer Communications 2022, 181, 236–256. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2021.10.016. [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.N.; Rahman, M.M.; Billah, M.M.; Saha, D. Internet of Things (IoT): A Review of Its Enabling Technologies in Healthcare Applications, Standards Protocols, Security, and Market Opportunities. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 10474–10498. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2021.3062630. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kashoash, H.A.; Kemp, A.H. Comparison of 6LoWPAN and LPWAN for the Internet of Things. Australian Journal of Electrical and Electronics Engineering 2016, 13, 268–274. [CrossRef]

- Hariharakrishnan, J.; Bhalaji, N. Adaptability Analysis of 6LoWPAN and RPL for Healthcare applications of Internet-of-Things. Journal of ISMAC 2021, 3, 69–81. [CrossRef]

- Verma, H.; Chauhan, N.; Awasthi, L.K. Modelling Buffer-Overflow in 6LoWPAN-Based Resource-Constraint IoT-Healthcare Network. Wireless Personal Communications 2023, pp. 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Azzawi, M.A.; Hassan, R.; Bakar, K.A.A. A review on Internet of Things (IoT) in healthcare. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research 2016, 11, 10216–10221.

- Ketu, S.; Mishra, P.K. Internet of Healthcare Things: A contemporary survey. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2021, 192, 103179. [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Ranga, V. Security of RPL based 6LoWPAN Networks in the Internet of Things: A Review. IEEE Sensors Journal 2020, 20, 5666–5690. [CrossRef]

- Chacko, A.; Hayajneh, T. Security and privacy issues with IoT in healthcare. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Pervasive Health and Technology 2018, 4, e2–e2. [CrossRef]

- Internet of Things project - owasp. https://wiki.owasp.org/index.php/OWASP_Internet_of_Things_Project#tab=Medical_Devices, 2018.

- Mamdouh, M.; Awad, A.I.; Khalaf, A.A.; Hamed, H.F. Authentication and identity management of IoHT devices: Achievements, challenges, and future directions. Computers & Security 2021, 111, 102491. [CrossRef]

- Shahid, J.; Ahmad, R.; Kiani, A.K.; Ahmad, T.; Saeed, S.; Almuhaideb, A.M. Data protection and privacy of the internet of healthcare things (IoHTs). Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 1927. [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, K.; Alam, T.M.; Hameed, I.A.; Khan, W.A.; Abbas, N.; Luo, S. A review on security challenges in internet of things (IoT). 2021 26th international conference on automation and computing (ICAC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Mayzaud, A.; Badonnel, R.; Chrisment, I. A Taxonomy of Attacks in RPL-based Internet of Things. International Journal of Network Security 2016, 18, 459–473.

- Boudouaia, M.A.; Ali-Pacha, A.; Abouaissa, A.; Lorenz, P. Security against rank attack in RPL protocol. IEEE Network 2020, 34, 133–139. [CrossRef]

- A. Almusaylim, Z.; Jhanjhi, N.; Alhumam, A. Detection and mitigation of RPL rank and version number attacks in the internet of things: SRPL-RP. Sensors 2020, 20, 5997. [CrossRef]

- Sahraoui, S.; Henni, N. SAMP-RPL: secure and adaptive multipath RPL for enhanced security and reliability in heterogeneous IoT-connected low power and lossy networks. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2021, pp. 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Sahay, R.; Geethakumari, G.; Mitra, B. A holistic framework for prediction of routing attacks in IoT-LLNs. The Journal of Supercomputing 2022, 78, 1409–1433. [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, C.; Poplade, D.; Nogueira, M.; Santos, A. Detection of sinkhole attacks for supporting secure routing on 6LoWPAN for Internet of Things. 2015 IFIP/IEEE International Symposium on Integrated Network Management (IM). IEEE, 2015, pp. 606–611. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, J.; Malik, A.W.; ur Rehman, A. Detection and prevention of Black Hole Attacks in IOT & WSN. 2018 third international conference on fog and mobile edge computing (FMEC). IEEE, 2018, pp. 217–226. [CrossRef]

- Mathur, A.; Newe, T.; Rao, M. Defence against black hole and selective forwarding attacks for medical WSNs in the IoT. Sensors 2016, 16, 118. [CrossRef]

- Attias, V.; Vigneri, L.; Dimitrov, V. Preventing denial of service attacks in IoT networks through verifiable delay functions. GLOBECOM 2020-2020 IEEE Global Communications Conference. IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xi, M.; Tang, Y. Recognition of grey hole attacks in wireless sensor networks using fuzzy logic in IoT. Transactions on Emerging Telecommunications Technologies 2020, 31, e3873. [CrossRef]

- Pasikhani, A.M.; Clark, J.A.; Gope, P.; Alshahrani, A. Intrusion detection systems in RPL-based 6LoWPAN: A systematic literature review. IEEE Sensors Journal 2021, 21, 12940–12968. [CrossRef]

- K, K.; Balaji, N. Analyze Black Hole Attack in RPL Using Cooja Environment. JETIR 2022, 9, c142–c148.

- Sahay, R.; Geethakumari, G.; Mitra, B.; Goyal, N. Investigating packet dropping attacks in RPL-DODAG in IoT. 2019 IEEE 5th International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, A.; Mayzaud, A.; Badonnel, R.; Chrisment, I.; Schönwälder, J. Addressing DODAG inconsistency attacks in RPL networks. 2014 Global Information Infrastructure and Networking Symposium (GIIS). IEEE, 2014, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Tmote-Sky: Ultra low power IEEE 802.15.4 compliant wireless sensor module. https://insense.cs.st-andrews.ac.uk/files/2013/04/tmote-sky-datasheet.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).